Mini Abdomen Experience: A Novel Approach for Mini-Abdominoplasty Minimally Invasive (MAMI) Abdominal Contouring

Abstract

1. Introduction

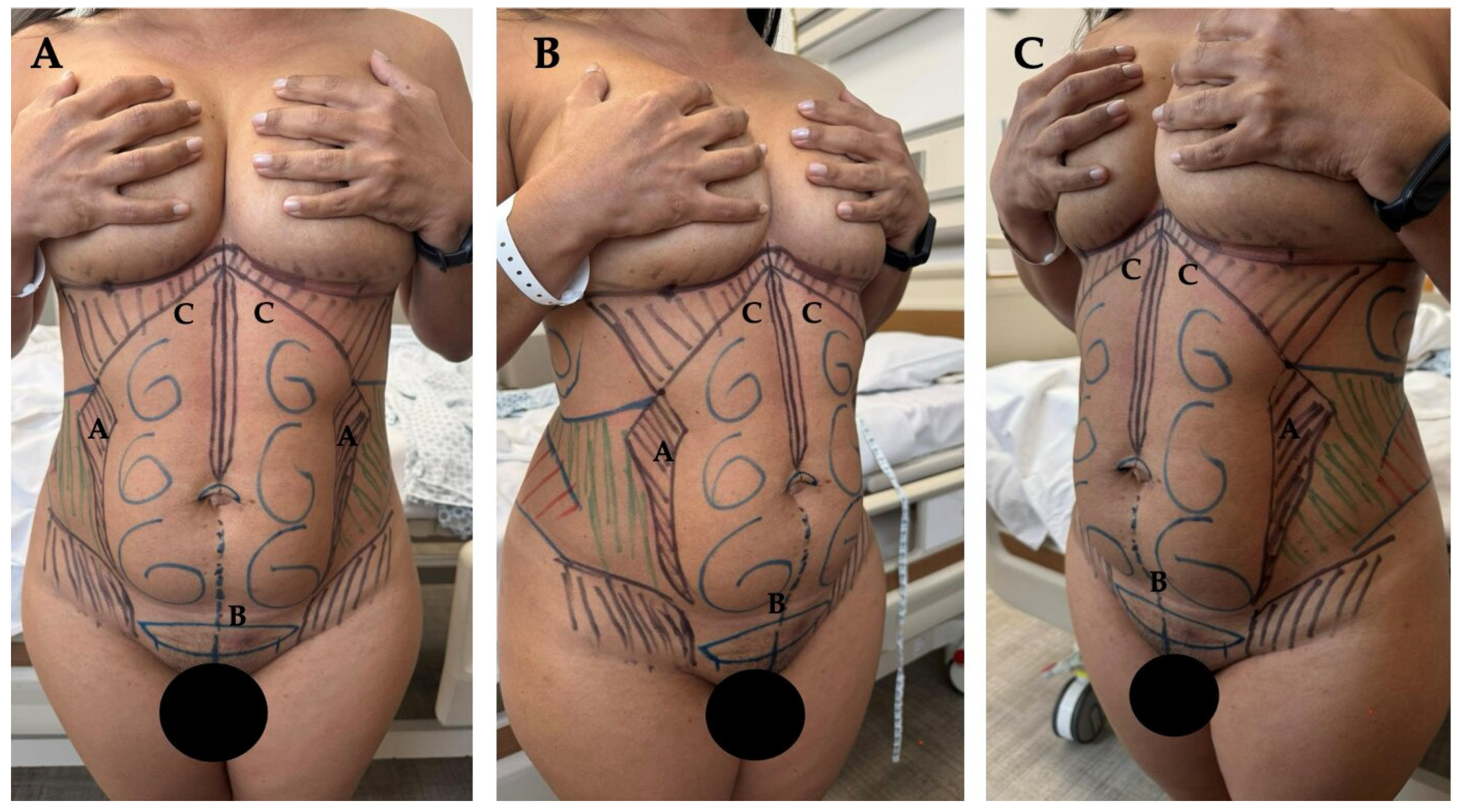

2. Ideas

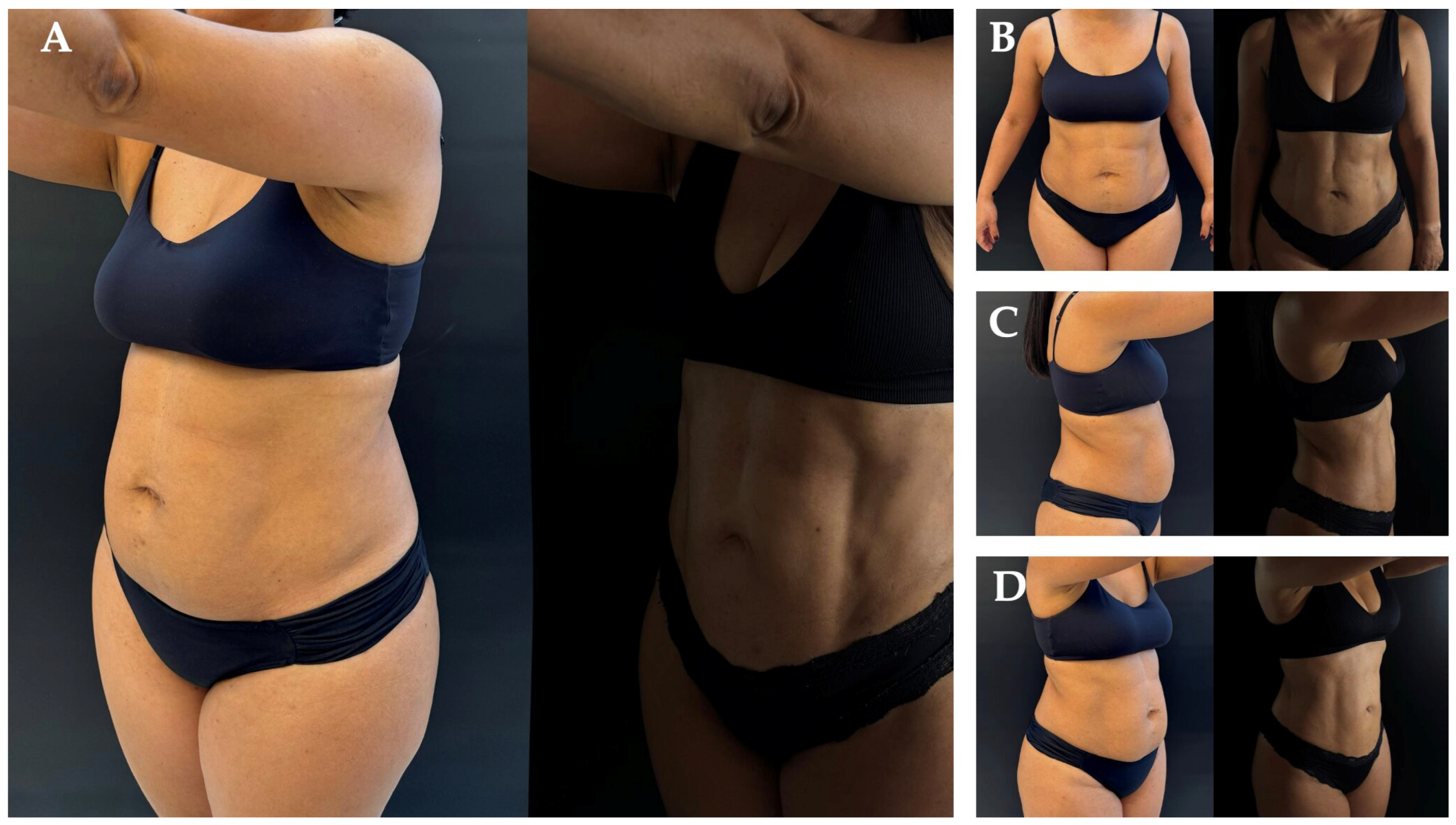

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akram, J.; Matzen, S.H. Rectus abdominis diastasis. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2014, 48, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperstad, J.B.; Tennfjord, M.K.; Hilde, G.; Ellström-Engh, M.; Bø, K. Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: Prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hernández-Granados, P.; Henriksen, N.A.; Berrevoet, F.; Cuccurullo, D.; López-Cano, M.; Nienhuijs, S.; Ross, D.; Montgomery, A. European Hernia Society guidelines on management of rectus diastasis. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turan, V.; Colluoglu, C.; Turkyilmaz, E.; Korucuoglu, U. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekol. Pol. 2011, 82, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lelli, G.; Iossa, A.; DEAngelis, F.; Micalizzi, A.; Fassari, A.; Soliani, G.; Cavallaro, G. Mini-invasive surgery for diastasis recti: An overview on different approaches. Minerva Surg. 2025, 80, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mommers, E.H.H.; Ponten, J.E.H.; Al Omar, A.K.; de Vries Reilingh, T.S.; Bouvy, N.D.; Nienhuijs, S.W. The general surgeon’s perspective of rectus diastasis. A systematic review of treatment options. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 4934–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peltz, G.; Aguirre, M.T.; Sanderson, M.; Fadden, M.K. The role of fat mass index in determining obesity. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2010, 22, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hubner, P.N.V.; Alberti, L.R.; Carvalho, A.C.; Soares, V.C.; Neto, C.S.; Garcia, D.P.C. Morphometric evaluation of the linea alba in fresh corpses. JPRAS Open 2024, 40, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faria-Correa, M.A. Robotic Procedure for Plication of the Muscle Aponeurotic Abdominal Wall. In New Concepts on Abdominoplasty and Further Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Faria-Correa MA, Videoendoscopy in plastic surgery: Brief communication. Rev. Soc. Bras. Cir. Plast. Est. Reconst. 1992, 7, 80–82.

- Faria-Correa, M.A. Abdominoplasty: The South America style. In Endoscopic Plastic Surgery; Ramirez, O.M., Daniel, R.K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Faria-Correa, M.A. Abdominoplastia videoendoscopica (subcutaneoscopica). In Atualizacao em Cirurgia Plastica Estetica e Reconstrutiva; Robe Editorial: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.T.; Sahoo, M.R. Laparoscopic plication and mesh repair for diastasis recti: A case series. Int. J. Case Rep. Images 2014, 5, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chai, Y.; Cao, C.; Jin, K.; Hu, Z. Laparoscopic versus open incisional and ventral hernia repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, E.M.; Di Biasio, G. Alternativa de manejo miniinvasivo para el tratamiento de pacientes con diástasis abdominal y colgajo dermograso mediante la táctica VER: Vaser® + endoscopia + Renuvion®. Rev. Argent. Cirugía Plástica 2022, 28, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, M.A. Videoendoscopic subcutaneous techniques for aesthetic and reconstructive plastic surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1995, 96, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Cano, M. Editorial: Rectus Diastasis. J. Abdom. Wall Surg. 2025, 4, 14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Greminger, R.F. The mini-abdominoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1987, 79, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Diego, J.M. Endoscopic Lipoabdominoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bank, D.E.; Perez, M.I. Skin Retraction After Liposuction in Patients Over the Age of 40. Dermatol. Surg. 1999, 25, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, C.M.P.; Malcher, F.; Cavazzola, L.T.; Furtado, M.; Morrell, A.; Azevedo, M.; Meirelles, L.G.; Santos, H.; Garcia, R. Subcutaneous Onlay Laparoscopic Approach (Scola) for Ventral Hernia and Rectus Abdominis Diastasis Repair: Technical Description and Initial Results. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2018, 31, e1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malcher, F.; Lima, D.L.; Lima, R.N.C.L.; Cavazzola, L.T.; Claus, C.; Dong, C.T.; Sreeramoju, P. Endoscopic onlay repair for ventral hernia and rectus abdominis diastasis repair: Why so many different names for the same procedure? A qualitative systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 5414–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, C.M.P.; DI-Biasio, G.A.; Ribeiro, R.D.; Correa, M.A.M.F.; Pagnoncelli, B.; Palmisano, E. Minimally invasive lipoabdominoplasty (MILA) tactic. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2024, 51, e20243692, (In English, Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, T.S. Mini-abdominoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1988, 82, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, C.H.; Walters, N.; Stroh, R.; Munavalli, G. New Technologies in Skin Tightening. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 2021, 9, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Correa, M.A. MILA-Minimally Invasive Robotic and Endoscopic Lipo-Abdominoplasty. In Body Contouring: Current Concepts and Best Practices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galhego, R.F.; Martins, T.; Carvalho, A.C.; Faria-Correa, M.; Nogueira, R. Mini Abdomen Experience: A Novel Approach for Mini-Abdominoplasty Minimally Invasive (MAMI) Abdominal Contouring. Surg. Tech. Dev. 2025, 14, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14020016

Galhego RF, Martins T, Carvalho AC, Faria-Correa M, Nogueira R. Mini Abdomen Experience: A Novel Approach for Mini-Abdominoplasty Minimally Invasive (MAMI) Abdominal Contouring. Surgical Techniques Development. 2025; 14(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalhego, Rodrigo Ferraz, Tulio Martins, Alvaro Cota Carvalho, Marco Faria-Correa, and Raquel Nogueira. 2025. "Mini Abdomen Experience: A Novel Approach for Mini-Abdominoplasty Minimally Invasive (MAMI) Abdominal Contouring" Surgical Techniques Development 14, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14020016

APA StyleGalhego, R. F., Martins, T., Carvalho, A. C., Faria-Correa, M., & Nogueira, R. (2025). Mini Abdomen Experience: A Novel Approach for Mini-Abdominoplasty Minimally Invasive (MAMI) Abdominal Contouring. Surgical Techniques Development, 14(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/std14020016