Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Leukemias in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Dwyer, K.; Freyer, D.R.; Horan, J.T. Treatment strategies for adolescent and young adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2018, 132, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, E.C.; Ducore, J.; Kwan, M.L.; Cheng, S.Y.; Bowles, E.J.A.; Greenlee, R.T.; Pole, J.D.; Rahm, A.K.; Stout, N.K.; Weinmann, S.; et al. Leukemia Risk in a Cohort of 3.9 Million Children with and without Down Syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2021, 234, 172–180.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasle, H.; Clemmensen, I.H.; Mikkelsen, M. Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down’s syndrome. Lancet 2000, 355, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.S.; Hunger, S.P. Optimal therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, W.; Luger, S.M.; Advani, A.S.; Yin, J.; Harvey, R.C.; Mullighan, C.G.; Willman, C.L.; Fulton, N.; Laumann, K.M.; Malnassy, G.; et al. A pediatric regimen for older adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of CALGB 10403. Blood 2019, 133, 1548–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.E.; Stock, W.; Johnson, R.H.; Advani, A.; Muffly, L.; Douer, D.; Reed, D.; Lewis, M.; Freyer, D.R.; Shah, B.; et al. Pediatric-Inspired Treatment Regimens for Adolescents and Young Adults with Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, J.S.; Sharaf, N.; O’Brien, A.R.W.; Batra, S.; Konig, H.; Skiles, J.L. Differences Between Pediatric and Adult Protocols and Medical Centers in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in the United States. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Lupo, P.J.; Shah, N.N.; Hitzler, J.; Rabin, K.R. Management of Down Syndrome-Associated Leukemias: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCI. Childhood Myeloid Proliferations Associated with Down Syndrome Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/hp/child-aml-treatment-pdq/myeloid-proliferations-down-syndrome-treatment-pdq#:~:text=Myeloid%20leukemias%20that%20arise%20in,%2C%20but%20not%20always%2C%20megakaryoblastic (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Purnell, J.Q. Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NCI. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_50 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Payne, R.B.; Little, A.J.; Williams, R.B.; Milner, J.R. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br. Med. J. 1973, 4, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2015, 219, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Galati, P.C.; Ribeiro, C.M.; Pereira, L.T.G.; Amato, A.A. The association between excess body weight at diagnosis and pediatric leukemia prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Rev. 2022, 51, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelelete, C.B.; Pereira, S.H.; Azevedo, A.M.; Thiago, L.S.; Mundim, M.; Land, M.G.; Costa, E.S. Overweight as a prognostic factor in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 1908–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsanipour, E.A.; Sheng, X.; Behan, J.W.; Wang, X.; Butturini, A.; Avramis, V.I.; Mittelman, S.D. Adipocytes cause leukemia cell resistance to L-asparaginase via release of glutamine. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2998–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramanik, R.; Sheng, X.; Ichihara, B.; Heisterkamp, N.; Mittelman, S.D. Adipose tissue attracts and protects acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from chemotherapy. Leuk. Res. 2013, 37, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.D.; Costello, A.G.; Shaw, P.H. A Comparison of Extremity Thrombosis Rates in Adolescent and Young Adult Versus Younger Pediatric Oncology Patients at a Children’s Hospital. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 6, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.R.; Patel, R.B.; Rahim, M.Q.; Althouse, S.K.; Batra, S. Venous Thromboembolic Events in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2022, 11, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimony, S.; Raman, H.S.; Flamand, Y.; Keating, J.; Paolino, J.D.; Valtis, Y.K.; Place, A.E.; Silverman, L.B.; Sallan, S.E.; Vrooman, L.M.; et al. Venous thromboembolism in adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on a pediatric-inspired regimen. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.H.; Rodriguez, V.; Lew, G.; Newburger, J.W.; Schultz, C.L.; Orgel, E.; Derr, K.; Ranalli, M.A.; Esbenshade, A.J.; Hochberg, J.; et al. Apixaban versus no anticoagulation for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia or lymphoma (PREVAPIX-ALL): A phase 3, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e27–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.; O’Brien, S.H.; Orgel, E.; Schultz, C.L.; Esbenshade, A.J.; Memaj, A.; Dyme, J.L.; Favatella, N.A.; Mitchell, L.G. on behalf of the, P.-A.L.L.i. Safety and efficacy of apixaban thrombosis prevention in pediatric patients with obesity and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 4738–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, E. Regulation of serum phosphate. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 3985–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Ganz, T.; Trumbo, H.; Seid, M.H.; Goodnough, L.T.; Levine, M.A. Parenteral iron therapy and phosphorus homeostasis: A review. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, V.J.; Nielsen, M.F.; Hannan, F.M.; Thakker, R.V. Hypercalcemic Disorders in Children. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 2157–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, N.R.; Cahill, H.; Diamond, Y.; McCleary, K.; Kotecha, R.S.; Marshall, G.M.; Mateos, M.K. Down syndrome-associated leukaemias: Current evidence and challenges. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2024, 15, 20406207241257901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Rau, R.E.; Kairalla, J.A.; Rabin, K.R.; Wang, C.; Angiolillo, A.L.; Alexander, S.; Carroll, A.J.; Conway, S.; Gore, L.; et al. Blinatumomab in Standard-Risk B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 392, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristic | Overall n = 27 | PED DS ALL n = 21 | AYA DS ALL n = 6 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | 4 (2–20) | 3 (2–12) | 17.0 (15.0–20.0) | <0.001 * | ||

| Sex | F | 11 (40.7%) | 8 (38.1%) | 3 (50.0%) | 0.6 | |

| M | 16 (59.3%) | 13 (61.9%) | 3 (50.0%) | |||

| Race | Asian | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0 | |

| African American | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| White | 20 (90.9%) | 16 (88.9%) | 4 (100.0%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0 | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 21 (91.3%) | 17 (89.5%) | 4 (100.0%) | |||

| BMI group | Underweight | 8 (29.6%) | 8 (38.1%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.06 | |

| Normal | 3 (11.1%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| Overweight | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (16.7%) | |||

| Obese | 1 (3.7%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (16.7%) | |||

| Unknown | 13 (48.1%) | 9 (42.9%) | 4 (66.7%) | |||

| Risk stratification | Standard risk | 6 (46.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.09 | |

| High risk | 6 (46.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (75.0%) | |||

| Very high risk | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (25.0%) | |||

| CNS Status | CNS1 | 23 (88.5%) | 18 (90.0%) | 5 (83.3%) | 0.5 | |

| CNS2 | 2 (7.7%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | |||

| CNS2B | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| BMI at diagnosis | 17.4 (14.4–35.5) | 17.2 (14.4–27.2) | 32.7 (29.8–35.5) | 0.036 * | ||

| Lab Value at Diagnosis | Overall n = 27 | PED DS ALL n = 21 | AYA DS ALL n = 6 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANC (/mm3) | 0.7 (0.1–8.7) | 0.8 (0.1–8.7) | 0.2 (0.1–4.8) | 0.7 |

| % Blasts Peripheral Smear (/mm3) | 67.5 (0–97) | 69.5 (0–97) | 56.0 (19.0–92.0) | 0.4 |

| WBC (/mm3) | 9.7 (2.2–366.5) | 13.6 (2.17–241.6) | 5.4 (5.2–366.5) | 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.6 (4–13) | 8.6 (4–12.6) | 8.4 (6.2–13.0) | 0.8 |

| Platelet (/mm3) | 40 (5–131) | 41.0 (5.0–131.0) | 39.0 (6.0–131.0) | 1.0 |

| LDH (U/L) | 670 (209–2612) | 771.5 (209–1700) | 625.0 (229.0–2612.0) | 0.8 |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 6.3 (3.4–10.1) | 6.4 (3.4–10.1) | 6.3 (6.2–8.1) | 0.6 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.2 (8.7–10.2) | 9.3 (8.7–10.2) | 9 (8.7–9.1) | 0.02 * |

| Adjusted Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.6 (8.9–10.4) | 9.2 (8.9–9.6) | 9.7 (9.1–10.4) | 0.02 * |

| Phosphorous (mg/dL) | 5.3 (3.4–6.8) | 5.4 (4.5–6.8) | 4 (3.4–4.6) | 0.004 * |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 (2.7–4.2) | 3.5 (2.7–4.2) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 0.8 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 129 (63–304) | 133.0 (63.0–304.0) | 102.0 (65.0–198.0) | 0.4 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 16 (5–26) | 14.5 (6–26) | 16.0 (5.0–17.0) | 0.8 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.5 (4–450) | 25.5 (4–100) | 40.5 (13–450) | 0.3 |

| AST (U/L) | 46 (8–291) | 40.5 (8–131) | 57.0 (19.0–291.0) | 0.4 |

| HTN, induction | 7 (28.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1.0 |

| VTE Occurrence | 5 (18.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | 0.056 |

| Febrile Neutropenia, Induction | 24 (88.9%) | 18 (85.7%) | 6 (100.0%) | 1.0 |

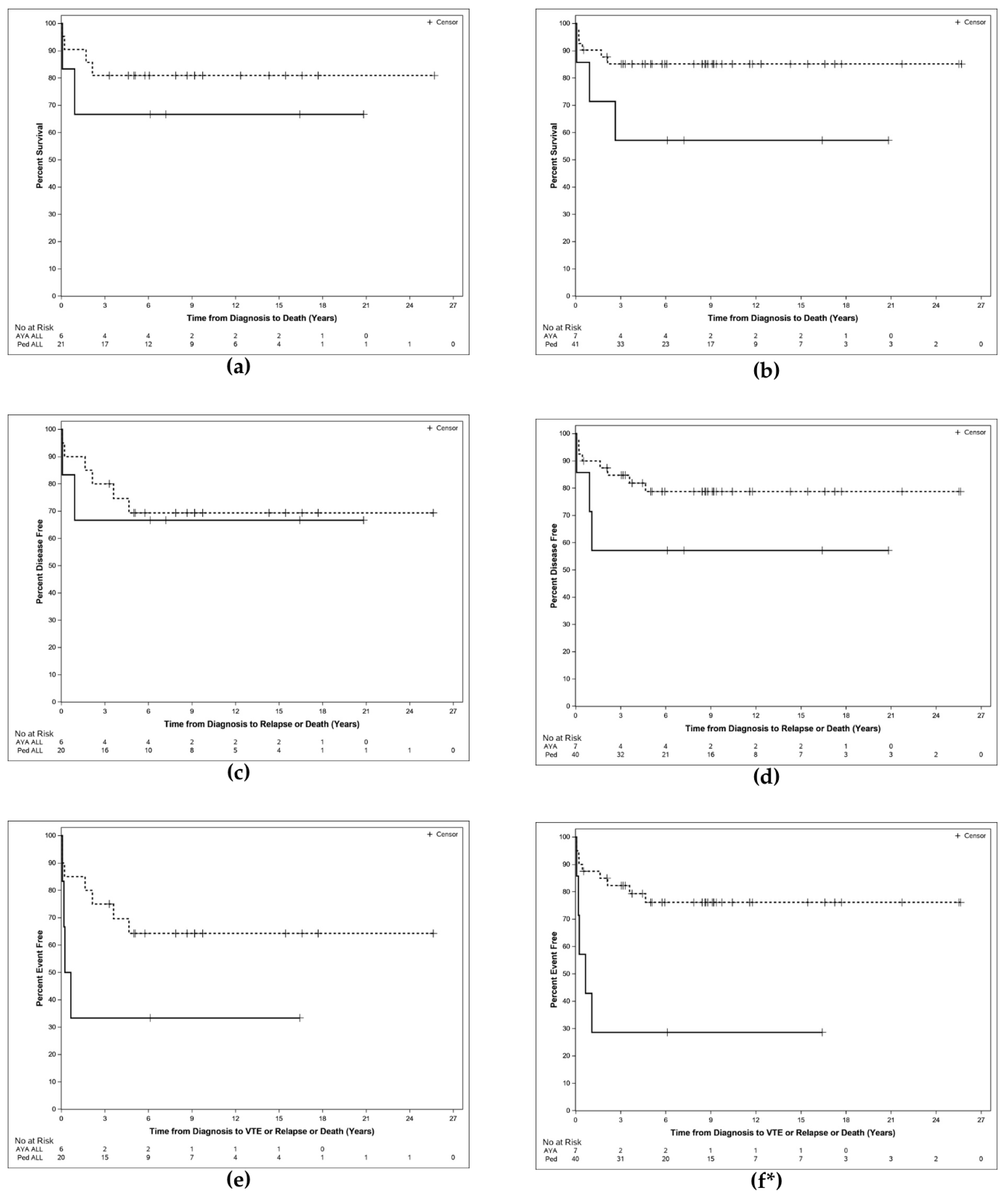

| Outcome | PED DS ALL | AYA DS ALL | Log Rank p-Value | PED DS (ALL + AML) | AYA DS (ALL + AML) | Log Rank p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival (OS) % | ||||||

| Median (years) | NR | NR | 0.4261 | NR | NR | 0.08 |

| 1-year probability | 90.5 | 66.7 | 90.2 | 71.4 | ||

| 2-year probability | 85.7 | 66.7 | 87.7 | 71.4 | ||

| Disease Free Survival (DFS) % | ||||||

| Median (years) | NR | NR | 0.7963 | NR | NR | 0.16 |

| 1-year probability | 90.0 | 66.7 | 90.0 | 71.4 | ||

| 2-year probability | 85.0 | 66.7 | 87.4 | 57.1 | ||

| Event Free Survival (EFS) % | ||||||

| Median (years) | NR | 0.4 | 0.0954 | NR | 0.6 | 0.002 |

| 1-year probability | 85.0 | 33.3 | 87.5 | 42.9 | ||

| 2-year probability | 80.0 | 33.3 | 84.9 | 28.6 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karam, M.N.; Althouse, S.K.; Andrews, M.G.; Chen, J.; Batra, S. Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Leukemias in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience. Hematol. Rep. 2025, 17, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17060070

Karam MN, Althouse SK, Andrews MG, Chen J, Batra S. Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Leukemias in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience. Hematology Reports. 2025; 17(6):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17060070

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaram, Marie Nour, Sandra K. Althouse, Madeline G. Andrews, Jenny Chen, and Sandeep Batra. 2025. "Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Leukemias in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience" Hematology Reports 17, no. 6: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17060070

APA StyleKaram, M. N., Althouse, S. K., Andrews, M. G., Chen, J., & Batra, S. (2025). Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Leukemias in Adolescents and Young Adults with Down Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience. Hematology Reports, 17(6), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17060070