1. Introduction

Cotton is a vital global agricultural commodity crop in food, feed, and industrial uses. The United States (U.S.) is among the world’s leading producers, ranking fourth globally with an annual output of 14.6 million bales of lint and a national average yield of 1059 kg ha

−1. The US’s cotton yield is well above the world average of 792 kg ha

−1 [

1]. Cotton is cultivated across a broad geographic extent in the U.S., from Virginia to California, with Texas, Georgia, and Mississippi as the top producing states [

1]. While the U.S. is the world’s largest cotton exporter, China remains the leading importer [

1,

2]. Like other crops, cotton growth and yield depends on the availability of both macro and micronutrients. The latter are only demanded by plants in trace quantities but are indispensable in sustaining the metabolic processes that drive cotton growth, reproduction, and fiber development.

Out of nearly 90 elements occurring naturally in soils, only a limited number are classified as essential micronutrients, and among them, iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), and boron (B) play critical roles in sustaining cotton yield [

3]. Each plays a unique role that directly influences cotton growth traits. Boron, for example, is essential for cell wall formation, membrane integrity, and reproductive structures formation [

4,

5]. Iron on the other hand regulates chlorophyll biosynthesis, photosynthetic electron transport, and energy metabolism [

6,

7,

8]. Manganese functions as a cofactor for enzymes in photosystem II, critical for lignin biosynthesis and oxidative stress regulation [

9]. Zinc contributes to auxin synthesis, enzyme activation, and reproductive organ development [

10]. These roles of micronutrients are linked to several physiological and molecular mechanisms that influence their effects on yield, yet their management has long been overshadowed by the emphasis on nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and sulfur (S) [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Given the global significance of cotton as both an economic and industrial crop, it is imperative to reevaluate the current advances, mechanisms, and contributions of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn in cotton growth and yield formation. This review integrates current physiological, molecular, and agronomic insights on B, Fe, Mn, and Zn in cotton. The overarching objective is to clarify their role in signaling pathways, transport mechanisms, and functional interactions in cotton, thereby defining opportunities for improving micronutrient use efficiency and identifying future research priorities.

2. Methodology

To ensure a comprehensive, transparent, and reproducible synthesis of current knowledge, this review employed a structured and systematic approach to identify scholarly work on the roles of boron, iron, manganese, and zinc in cotton. Additional emphasis was placed on mechanisms involved in micronutrient signaling, transport, and utilization in cotton.

A systematic literature search was conducted across major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The search primarily targeted studies published in English from January 2000 to March 2025 to capture contemporary advances in plant physiology, molecular genetics, and precision nutrient management. Earlier foundational studies (prior to 2000) were included selectively only when they provided essential insights into micronutrient functions or historical context for the development of current knowledge. Search terms combined keywords and Boolean operators such as “cotton” OR “Gossypium”) and “micronutrient” OR “boron” OR “iron” OR “manganese” OR “zinc”, “signaling” OR “transport” OR “homeostasis” OR “deficiency” OR “toxicity” OR “nutrient use efficiency” OR “NUE” OR “yield” OR “fiber quality” OR “gene expression” OR “breeding”.

Additional studies were identified through backward snowballing (reviewing reference lists) and forward citation tracking of seminal articles. Papers were included if they were peer-reviewed primary research articles, review papers, and authoritative book chapters. Studies were included if they directly evaluated the role of B, Fe, Mn, or Zn in cotton growth, physiology, molecular regulation, and agronomic performance. Additional studies investigating molecular mechanisms (transporters, transcription factors, hormonal regulation), nutrient signaling pathways, or breeding strategies for improved micronutrient use efficiency were also included. Mechanistic studies in model plants (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh., rice (Oryza sativa L.), and maize (Zea mays L.)) were incorporated when findings provided transferable insights relevant to cotton micronutrient biology. Non-English publications, studies where micronutrients were not the central focus, or where data lacked micronutrient-specific measurements and research on crops other than cotton unless supported by mechanistic generalizability were excluded.

All retrieved records were screened first by title and abstract to determine topical relevance. Full-text articles meeting preliminary criteria were reviewed in detail for eligibility. Key information was extracted into a structured matrix capturing study objectives, experimental design (field, greenhouse, or molecular laboratory data), cotton species or cultivar, nutrient source, and dosage. Insights on physiological responses, identified genes or proteins, and effects on yield or fiber-related traits were also noted. Extracted evidence was synthesized thematically to align with the objectives of this review. Themes included (a) physiological and phenotypic effects of micronutrient availability, (b) impacts on yield formation and fiber quality, (c) molecular and genetic mechanisms regulating micronutrient uptake and homeostasis, (d) micronutrient signaling and integrative pathways, (e) breeding innovations and technological tools for improving micronutrient use efficiency. A narrative synthesis was used to integrate findings, identify areas of consensus, highlight contradictions, and outline knowledge gaps. Figures and tables were constructed to summarize pathways, gene families, and agronomic outcomes across studies.

3. Effect of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn on Plant Growth and Development

Cotton’s growth phases from seedling, root development, vegetative, and reproductive growth and development are highly sensitive to the availability of all nutrients including micronutrients. The deficiencies in these nutrients often interact to exacerbate plant stress. For example, B deficiency impairs pollen tube growth during flowering, affecting flower fertilization [

18]. Similarly, B deficiency interferes with carbohydrate transport and reproductive growth, indirectly affecting the effectiveness of phosphorus and potassium applications [

19,

20]. Iron deficiency impairs chlorophyll formation, photosynthetic efficiency, and ultimately boll retention [

21]. Manganese shortages impair enzyme activity and photosynthetic water-splitting, and susceptibility to oxidative stress [

22]. Zn deficiency leads to shortened internodes, stunted growth, smaller leaves, and poor boll development [

23]. These micronutrient deficiencies not only reduce crop performance directly but also diminish the efficiency of applied macronutrients such as N and P. For instance, Fe and Zn are essential for nitrate reductase activity and protein synthesis [

24], meaning that their absence reduces the efficiency of N fertilization. This assertion is in line with several studies that observed yield reductions when these micronutrients are deficient compared with fertilized plots [

25,

26,

27].

4. Molecular Mechanisms of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn Utilization in Cotton

Micronutrients like B, Fe, Mn, and Zn are like tiny sparks that ignite cotton growth, driving higher yields. However, the excessive or poorly managed reliance on micronutrient fertilizers can pose environmental risks, including soil accumulation and toxicity that can disrupt nutrient balances [

41]. To grow more cotton with minimal environmental costs while improving micronutrient use efficiency (MUE), the plant’s ability to make the most of these nutrients is critical [

42]. While smarter farming practices help, the real game-changer lies in breeding cotton varieties that naturally excel at using these nutrients efficiently [

6,

43,

44]. Over the past 30 years, selective breeding has made great strides in enhancing how cotton plants handle B, Fe, Mn, and Zn [

21,

45]. Future yield gains will require greater attention to internal nutrient redistribution within the plant.

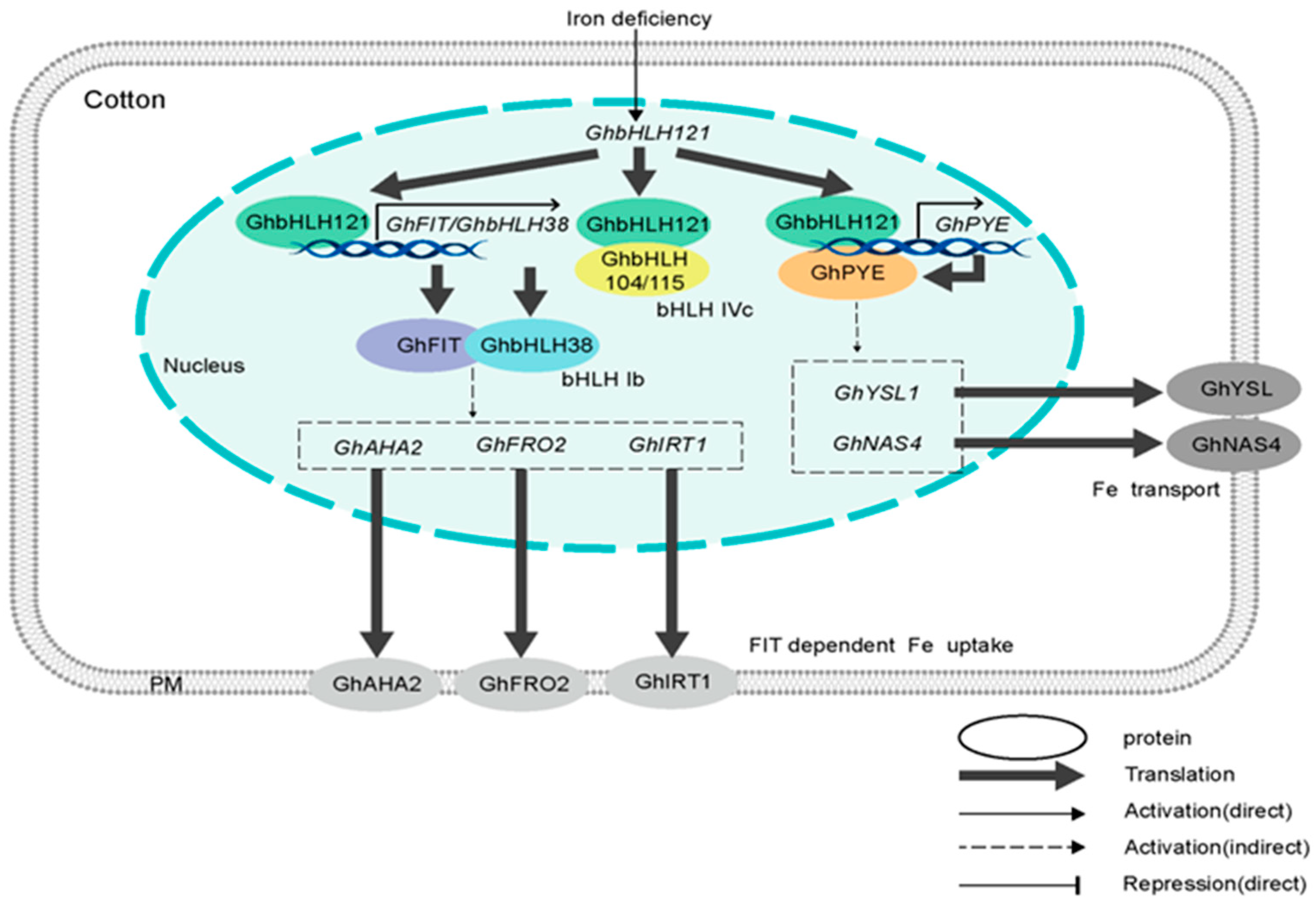

Under Fe-deficient conditions,

Gossypium hirsutum basic Helix–Loop–Helix 121 (GhbHLH121) gene expression is upregulated, indicating that it offers a starting point to understanding cotton’s iron deficiency response [

21]. The gene

GhbHLH121 forms heterodimers with

Gossypium hirsutum basic Helix–Loop–Helix 104 (

GhbHLH104) or

Gossypium hirsutum basic Helix–Loop–Helix 115 (GhbHLH115), independently activating the downstream expression of the three genes

Gossypium hirsutum basic Helix–Loop–Helix 38 (

GhbHLH38),

Gossypium hirsutum Fe-deficiency Induced Transcription factor (

GhFIT), and

Gossypium hirsutum POPEYE (

GhPYE), as shown in

Figure 5.

The downstream transcription factors

Gossypium hirsutum Fer-Like Iron Deficiency-Induced Transcription Factor (

GhFIT) and

Gossypium hirsutum POPEYE (

GhPYE) are critical for the plant’s adaptive response.

GhFIT functions as a central regulator of iron acquisition. Upon activation by the upstream Gossypium hirsutum basic helix–loop–helix 121 (

GhbHLH121) complex,

GhFIT promotes the expression of genes involved in rhizosphere acidification, such as proton-pumping adenosine triphosphatases (H

+-ATPases), and ferric iron reduction, such as ferric-chelate reductase-like enzymes (FRO-like enzymes), thereby enhancing the solubility and uptake of iron from the soil [

21,

31]

Furthermore,

GhPYE plays a pivotal role in managing internal iron homeostasis under deficiency stress. It orchestrates the remobilization and prioritization of iron within the plant, ensuring that the limited available iron is allocated to essential metabolic processes, thereby mitigating oxidative stress and supporting sustained growth [

21]. Therefore, the

GhbHLH121-mediated pathway coordinates a two-pronged strategy:

GhFIT acts to acquire more iron from the environment, while

GhPYE acts to conserve and optimize the use of existing iron reserves. This coordinated response enables adaptation to low iron availability.

When boron levels in the soil are low, cotton plants adjust their boron uptake efficiency (BUE) through root extensions to enhance absorption and fine-tune their internal processes to make better use of what is available. These adaptations to B uptake are driven by active root systems and optimized cellular functions that help maintain a healthy boron balance in the soil systems, especially with varieties bred for high BUE [

11,

20,

43,

46,

47]. Enzymes such as pectin methylesterases and expansins work together to maintain cell wall integrity, thereby enhancing resistance to lodging [

4,

43,

48]. Boron helps in maintaining cell wall structure and function through its involvement in the cross-linking of rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-II), a process mediated by enzymes such as UDP-glycosyltransferases that strengthen cell wall integrity. Concurrently, xyloglucan endotransglucosylases contribute to cell wall remodeling during growth and development [

48,

49]. Beyond structural functions, boron also modulates signaling pathways, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by oxidases act as key regulators of developmental processes and stress adaptation in cotton [

47,

50].

When soils are low in iron, plants actively respond to the deficiency. They release special compounds called phytosiderophores from their roots, which act like chemical “magnets” that bind tightly to iron in the soil. This process makes iron more available, allowing the plant to take it up more efficiently by increasing the activity of iron transporters in the roots [

21].

Table 1 summarizes iron uptake strategies in various crops, including upland cotton. The most common strategy is reduction-based, where the plant acidifies the rhizosphere, reducing Fe

3+ to Fe

2+. The reduced Fe

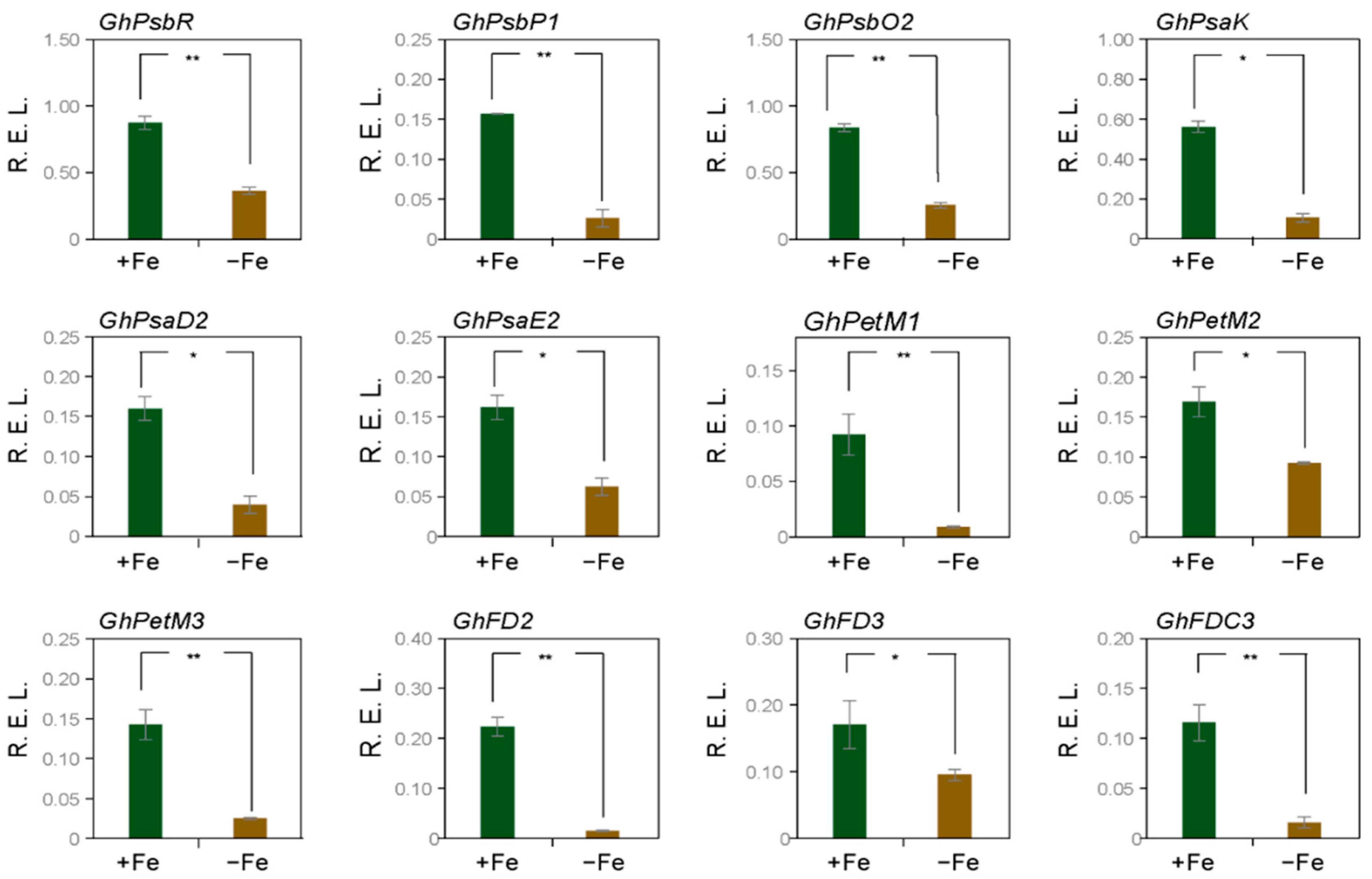

2+ is transported via specific transporters like Iron-Regulated Transporter 1 (IRT1). Cotton, for example, uses genes like GhbHLH121 as elucidated earlier to regulate responses to iron deficiency. Bioinformatics offers a systematic way to uncover the genetic networks that govern iron homeostasis in cotton. By profiling genes affected by iron deficiency as shown in

Figure 6, research can pinpoint key regulators of iron signaling and transport, creating opportunities to enhance iron acquisition. Plant mechanisms also incorporate enzyme activity. Enzymes such as ferredoxin and heme oxygenase adjust their activity to sustain iron mobilization and availability, ensuring continued photosynthetic efficiency and growth despite limited supply [

44].

For manganese and zinc shortages, cotton plants increase the production of metal tolerance proteins and zinc-regulated transporter protein (ZIP transporters), which act like gatekeepers to regulate the uptake and balance of these nutrients, ensuring the plant thrives despite limited supply [

9]. Under deficiency, alkaline phosphatase and zinc finger proteins become central to mobilizing zinc, regulating gene expression, and sustaining DNA replication and protein synthesis processes essential for fiber quality and seed development [

24,

25,

59].

4.1. Efficiency Genes and Hormonal Regulatory Mechanisms of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn in Plants

Boron uptake in plants is primarily mediated by the boron transporter (BOR) and nodulin 26-like intrinsic protein (NIP) families, with functional variation observed among species. In cotton, BOR family gene members have been identified to contribute to B export and tolerance. Specific transporters such as BOR1 and NIP5;1 are directly involved in B uptake, while others regulate B translocation and distribution [

7,

21,

50,

60]. Similarly, Fe, Mn, and Zn homeostasis in cotton is mediated by Zinc-Regulated/Iron-Regulated Transporter-Like Proteins (ZIPs) and Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Proteins (NRAMPs) [

24,

61]. In plant species related to cotton, ZIP genes have been identified. A study documented 14, 22, and 18 ZIP genes for Fe, Mn, and Zn transport, respectively, with collinearity analyses highlighting structural and functional conservation among these transporters [

24].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), known as oxygen derived free radical and non-radical species, further regulate micronutrient balance [

62,

63]. These are major byproducts of cellular activity with endogenous ROS accumulation enhancing tolerance under low micronutrient conditions. However, ROS action in plant pathology needs to be better understood and thus can be utilized in cotton. The action of ROS adds another dimension to adaptive responses to micronutrient stress that include modifications in root morphology, the exudation of organic acids, enhanced membrane and intracellular transport, and the induction of high-affinity transporter genes. These mechanisms facilitate the improved uptake and utilization of micronutrients [

60]. In Arabidopsis for example, transcription factors such as FIT and bHLH regulate Fe deficiency when activated by MYB proteins including MYB30 and MYB121 to enhance its distribution in plants [

64]. Homologous genes in cotton, including

GhbHLH121,

GhZIP, and

GhNRAMP, have been identified as key regulators of micronutrient acquisition and utilization, underscoring conserved regulatory mechanisms across species [

21,

51,

65].

4.2. Hormonal Regulation of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn

Plant hormones act as master regulators of cotton growth and development. Hormones coordinate diverse physiological responses to environmental and nutritional signals. Among them, auxins, cytokinins (CTKs), abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), gibberellins (GAs), brassinosteroids (BRs), jasmonic acid (JAs), salicylic acid (SA), and strigolactones (SL) stand out. These play central roles in mediating cotton’s adaptation to the availability of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. ABA has been shown to regulate Fe-driven lateral root formation, with ABA-dependent signaling pathways promoting root development and enhancing Fe redistribution from roots to shoots in both cotton and model systems like Arabidopsis [

68]. CTKs serve as long-distance messengers of nutrient status, relaying Zn and Fe utilization signals via the xylem. Genes such as

AtIPT3 and

AtIPT5, which govern CTK biosynthesis under Zn and Fe stress in Arabidopsis, appear to function through similar pathways in cotton roots which influence nutrient uptake [

69].

The interplay between Fe and GAs has been widely reported, with growth regulator factor 4 (GRF4) identified as a key player in Fe uptake and biomass partitioning. Despite this being reported in rice, comparable functions are proposed for cotton [

70]. Brassinosteriod signaling kinase 3 (BSK3), essential for root elongation under Fe deficiency in Arabidopsis, points to potential BR–Fe crosstalk in shaping cotton root architecture under nutrient stress [

35,

70]. Likewise, the application of ethephon, an ETH-releasing compound, improves Zn utilization efficiency by enhancing enzyme activity linked to Zn metabolism. Peptide hormones such as CEPD1 and CEPD2, which stimulate IRT1 expression and promote Fe uptake in Arabidopsis, may also have analogous functions in cotton nutrient transport. Under B deficiency, SA, ABA, and JA converge on WRKY75, a transcription factor that modulates auxin-mediated lateral root elongation and density, ultimately affecting cell wall stability and root morphology in cotton [

66]. In a similar way, excess Mn disrupts IAA balance, accelerating IAA oxidation and altering root development, underscoring the interaction between hormones and micronutrient signaling [

9,

34,

35]. A detailed summary of hormonal pathways is shown in

Table 2.

4.3. Signal Integration of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn

While the signaling pathways of these micronutrients have been extensively studied individually, their interactions remain poorly understood [

11,

41,

77]. Emerging evidence indicates that the integration of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn uptake represents an evolutionary adaptation that enables plants to maintain a balanced nutrient profile [

36,

52]. Significant progress has been achieved in identifying the key regulatory components governing B-Fe-Mn-Zn interactions in model species such as Arabidopsis and rice [

77]. Although research in cotton is limited, available molecular insights suggest promising opportunities to enhance boron use efficiency, iron use efficiency (IUE), manganese use efficiency (MUE), and zinc use efficiency (ZUE) [

21,

24,

34,

35,

78]. Current findings reveal a complex network that integrates B, Fe, Mn, and Zn signaling pathways, offering a clearer understanding of their interdependence (

Table 3).

4.4. Signaling Integration of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn in Root Development

Local B supply promotes lateral root elongation [

72], while excess Mn induces short, highly branched roots in cotton, altering nutrient uptake [

80]. Boron deficiency can have a two-way effect on plant growth. Boron deficiency can either promote or suppress taproot growth. Suppression is linked to blue light-induced Fe redox reactions near roots that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly under combined B and Fe deficiency in calcareous soils [

43,

65,

81]. Boron–Zn interactions further regulate root nutrient dynamics. Adequate B enhances Mn and Fe accumulation while maintaining balanced Mn/Fe ratios, supporting root health. In contrast, B deficiency upregulates ACS11, increasing ethylene biosynthesis, the auxin-mediated inhibition of root elongation, and ROS production. For example, Zn supplementation, including ZnO nanoparticles, were found to alleviate B toxicity by improving root biomass, reducing ROS, and enhancing Fe and Mn transporter activity [

82]. At the molecular level, the Arabidopsis transcription factor (AtNIGT1) has been found to integrate B and Zn signals, with homologs likely functioning in cotton [

71,

82]. B induces Arabidopsis thaliana Nitrate-Inducible GARP-Type Transcriptional Repressor 1 (AtNIGT1) via

BOR1, while Zn deficiency reduces its stability [

83]. This dual regulation modulates taproot growth, with AtNIGT1 suppressing taproot elongation under B deficiency but only in the presence of Zn, coordinating with Fe and Mn signals to maintain root structure. The

BOR1-AtNIGT1 module thus links B and Zn cues to the downstream regulation of root development [

83].

4.5. B-Fe-Mn-Zn Signaling Integration to Regulate Cotton Boll Development

Boron, iron, manganese, and zinc availability plays a pivotal role in boll formation and maturation in cotton by influencing reproductive structures and yield. Adequate boron supply enhances boll weight and reduces boll shedding, while manganese excess can disrupt iron homeostasis. This leads to reduced boll nutrient content, as seen in studies where high Mn/Fe ratios impair fiber quality [

11,

24,

25]. Low-Zn conditions impair boll development by limiting enzyme activities, exacerbating iron and manganese imbalances that affect cell wall integrity in bolls. This is pronounced under calcareous soils where Zn availability is low [

11,

84].

In cotton, the interaction between B and Zn affects Fe and Mn content in bolls. Boron promotes the transport of Fe and Mn to reproductive tissues, as evidenced by increased boll micronutrient levels under combined B-Zn application [

11,

80]. Boron deficiency inhibits pollen tube growth and boll setting. However, zinc supplementation has been documented to mitigate this by stabilizing membrane functions and hormone signaling, leading to higher boll retention and seed quality [

24]. Transcription factors like

GhbHLH121 integrate Fe and Zn signals to regulate boll gene expression under deficiency, coordinating with boron transporters for nutrient allocation and influencing fiber elongation [

21,

60]. Optimal B-Zn ratios ensure balanced Mn/Fe uptake, preventing oxidative stress in bolls and improving fiber quality, with foliar applications of Zn, Fe, and B significantly boosting boll yield.

4.6. B, Fe, Mn, and Zn Signaling Integration to Regulate Cotton Response to Stress

Boron, iron, manganese, and zinc are integral to cotton’s stress response mechanisms, modulating antioxidant defenses and nutrient homeostasis under abiotic stresses like toxicity or deficiency [

4,

85,

86,

87]. Boron toxicity increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation; however, zinc mitigates this stress by enhancing the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), thereby reducing hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in both roots and leaves, as demonstrated in cotton seedlings treated with zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles [

59,

66,

88]. Manganese and iron interactions under stress influence redox balance. Excess Mn disrupts Fe uptake and exacerbates oxidative damage, particularly in acidic soils where Mn toxicity is prevalent [

35].

In cotton, ZnO nanoparticles have been shown to upregulate ABC transporter genes and photosynthesis pathways to counter boron stress. These genes signal and set in motion processes that lead to nutrient redistribution and stress tolerance [

59,

85]. Boron interacts with Zn to modulate hormone signaling (e.g., jasmonic acid), enhancing resilience to toxicity, with foliar Zn reducing B-induced growth inhibition. Under calcareous soil conditions, balanced B, Zn, Fe, and Mn ratios improve membrane integrity and reduce susceptibility to environmental cues like salinity. In one study, nano-Zn applications mitigated salt stress by maintaining ionic homeostasis [

26]. Heat stress responses are alleviated by micronutrient sprays, including Mn and Zn, which upregulate defense genes and reduce oxidative damage in cotton [

89]. More details are elucidated in

Table 4.

4.7. B, Fe, Mn, and Zn Signaling Integration Regulating Nutrient Uptake

The AtNIGT1s family (AtNIGT1.1–1.4) plays a central role in nutrient regulation by repressing B-starvation-induced genes (e.g.,

BOR1,

NIP5;1) and controlling Zn-starvation-responsive genes (

ZIP2/4,

HMA2/4). These set in motion processes that lead to enhanced Zn utilization. AtNIGT1 expression is induced by high B and Zn deficiency and regulated by transcription factors AtbHLH121 and AtMYB13, linking B and Zn signaling pathways [

48,

76,

90]. Boron directly promotes Zn utilization [

11,

80]. In rice and cotton, the B transporter

BOR1 activates Zn-starvation-induced (ZSI) genes by interacting with SPX4-like proteins, leading to SPX4 degradation, MYB translocation into the nucleus, and the induction of Zn-responsive genes [

46,

65,

71]. This BOR1–SPX4–MYB axis exemplifies B–Zn crosstalk, where boron signaling co-activates both B- and Zn-responsive pathways.

The bHLH transcription factors also contribute to B signaling via cytoplasmic–nuclear shuttling [

21,

60]. Furthermore, SPX4 coordinates MYB13 (Zn signaling) and bHLH121 (B signaling), forming a unified BOR1–SPX4–bHLH121–MYB13 cascade that integrates B and Zn responses [

21,

60]. BOR1 and SPX4 are regulated through ubiquitination by plasma membrane-localized E3 ubiquitin ligases. Under toxic B conditions, BOR1 is targeted for degradation, preventing excess B accumulation [

59,

66,

88]. This BOR1–SPX module transduces B signals to core transcription factors, enabling the synergistic regulation of B- and Zn-responsive genes [

91]. Downstream, MYB, bHLH, and NIGT1 sustain B–Zn homeostasis under fluctuating environments [

92].

Beyond Zn, B also influences Mn utilization by regulating Mn concentration and assimilation. Boron reduces free Mn levels by repressing

NRAMP1, and activates

MTP11, while stimulating Mn superoxide dismutase activity. This demonstrates B’s role in linking Mn and Zn regulation [

93]. In cotton, B–Fe–Mn–Zn integration extends to macronutrient uptake. B enhances N and K absorption but reduces P and Fe translocation under high B. Zinc promotes N and K uptake while antagonizing P and Fe and also affects sulfur metabolism through enzyme activation [

11,

94]. Although the molecular basis of B–Fe–Mn–Zn signaling in cotton remains limited and unclear, evidence from model plants shows that these micronutrients function both independently and interactively, coordinating with macronutrient (N, P, K, S) uptake (

Table 5).

5. Recent Approaches for Breeding Nutrient-Efficient Cotton Varieties

The natural variation in micronutrient efficiency among cotton genotypes provides an opportunity to breed varieties with both high yield potential and improved NUE. High-throughput phenotyping, particularly using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with multispectral and hyperspectral sensors, now enables the precise assessment of chlorophyll content, biomass, and micronutrient status [

95]. With these abilities, these technologies allow the detection of nutrient deficiency symptoms [

95]. However, cotton’s complex canopy and inconsistent correlations between biomass and yield under variable micronutrient conditions remain a major challenge [

1]. Advances in UAV imaging and precision cameras are expected to overcome these limitations, enabling more accurate trait measurement [

96,

97].

Integrating UAV-based phenotyping with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) facilitates the discovery of genes controlling B, Fe, Mn, and Zn efficiency [

95]. Field trials with gradient micronutrient treatments can further improve screening accuracy while conserving resources. Genes such as

GhbHLH121 (Fe regulation) and

GhZIP3 (Zn uptake) enhance NUE and yield stability under deficiency, while

BOR1 and

NRAMP1 regulate B and Mn transport [

21,

60].

Breeding strategies can build on identifying and prioritizing the regulation of such genes into elite cotton lines. For example, the regulation of

BOR1 influences B deficiency-related reproductive success, while enhanced

IRT1 affects Fe and Zn uptake under calcareous soils [

46,

65,

71,

98]. Such targets provide a molecular framework for breeding strategies. Marker-assisted selection (MAS), CRISPR-based editing, and transgenic approaches targeting genes such as

GhMTP11 (Mn homeostasis) are producing varieties with balanced micronutrient uptake and improved fiber quality [

79]. Lessons from model plants like

Arabidopsis and rice continue to inform these efforts (

Table 6).

6. Future Research Directions for B, Fe, Mn, and Zn Efficiency in Cotton

The physiology of B, Fe, Mn, and Zn uptake, assimilation signaling, and efficiency in cotton is increasingly receiving attention. However, the genetic, hormonal pathways and technological advances remain underexplored compared with other crops such as corn and soybeans. Insights from corn, soybeans, and other plants highlight that there is a potential to improve cotton’s NUE and yield stability. Future research should focus on high-throughput phenotyping using UAV-based imaging, combined with genome-wide association studies (GWAS), among other molecular techniques for identifying nutrient-efficient genotypes. Breeding strategies incorporating marker-assisted selection and CRISPR editing, for instance, overexpressing BOR1 or IRT1, or editing GhMTP11, can enhance micronutrient uptake, fiber quality, and stress tolerance. Research focusing on nutrient interactions with macronutrients (N, P, K, S), adaptation to environmental stresses, and sustainable nutrient management is highly recommended. Integrating genetic improvements with precision fertilization, biofortification, and sensor-guided application can optimize nutrient efficiency, reduce environmental impact, and support high-yield, resilient cotton production

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review synthesizes the pivotal roles of boron, iron, manganese, and zinc in cotton physiology, signaling integration, and nutrient use efficiency. It also addresses yield gaps often overlooked in macronutrient-focused programs. The key findings demonstrate that these micronutrients regulate photosynthesis, hormone signaling, stress tolerance, and reproductive success. In most cases, micronutrient deficiencies are exacerbated by soil pH and interplant nutrient interactions. On a molecular level, genes such as BOR1, IRT1, and GhZIP3 provide targets for optimization. Looking ahead, a systems approach integrating advances in microRNA research, CRISPR-based gene editing, UAV phenotyping, and precision nutrition offer promising pathways to enhance micronutrient use efficiency, mitigate environmental challenges, and sustain high-yield cotton production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: U.A., A.H., D.N.Y., S.K., and F.A.; methodology: U.A. and D.N.Y.; software: U.A. and D.N.Y.; validation: U.A., A.H., and F.A.; formal synthesis: U.A., A.H., D.N.Y., S.K., and F.A.; investigation: U.A., A.H., D.N.Y., S.K., and F.A.; resources, U.A. and D.N.Y.; data curation, U.A., A.H., and D.N.Y.; writing—original draft preparation: U.A., D.N.Y., and S.K.; writing—review and editing: U.A., D.N.Y., A.H., and F.A.; supervision: U.A. and D.N.Y.; project administration: U.A. and D.N.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data for this article is contained within it. For additional information, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) took full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| NUE | Nutrient Use Efficiency |

| BUE | Boron Use Efficiency |

| IUE | Iron Use Efficiency |

| MUE | Manganese Use Efficiency |

| ZUE | Zinc Use Efficiency |

| N, P, K, S | Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium, Sulfur |

| IRT1 | Iron-Regulated Transporter 1 |

| BOR1 | Boron Transporter 1 |

| NIP5;1 | Nodulin 26-like Intrinsic Protein 5;1 |

| ZIP | Zinc/Iron-Regulated Transporter-like Protein family |

| NRAMP1 | Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein 1 |

| MTP11 | Metal Tolerance Protein 11 |

| HMA2/HMA4 | Heavy Metal ATPase 2/4 |

| GhbHLH121 | Basic Helix–Loop–Helix transcription factor in cotton |

| GhZIP3 | Zinc Transporter gene in cotton |

| GhMTP11 | Cotton Metal Tolerance Protein gene |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| miR169, miR398, miR408 | Specific microRNAs involved in nutrient regulation |

| NFYA | Nuclear Factor Y subunit A |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RG-II | Rhamnogalacturonan II |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| CTK/CTKs | Cytokinins |

| ETH | Ethylene |

| GA/GAs | Gibberellins |

| BR/BRs | Brassinosteroids |

| JA/JAs | Jasmonic Acid |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| SL | Strigolactones |

| IAA | Indole-3-Acetic Acid (Auxin) |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| scRNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Studies |

| MAS | Marker-Assisted Selection |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

References

- Arinaitwe, U. Optimizing Corn and Cotton Performance with Adaptive Management Systems and Subsurface Drip Irrigation in the Mid-Atlantic USA. Ph.D. Thesis, The Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Suffolk, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, L.; Dew, T. Cotton and Wool Outlook: May 2023. USDA ERS. 2023. Available online: https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/outlooks/106526/CWS-23e.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Ahmed, N.; Ali, M.A.; Hussain, S.; Hassan, W.; Ahmad, F.; Danish, S. Essential micronutrients for cotton production. In Cotton Production and Uses: Agronomy, Crop Protection, and Postharvest Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rosolem, C.A.; Bogiani, J.C. Physiology of boron stress in cotton. In Stress Physiology in Cotton; The Cotton Foundation: Cordova, TN, USA, 2011; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nesic, A.; Meseldzija, S.; Onjia, A.; Cabrera-Barjas, G. Impact of crosslinking on the characteristics of pectin monolith cryogels. Polymers 2022, 14, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cao, X.; Jia, X.; Liu, L.; Cao, H.; Qin, W.; Li, M. Iron deficiency leads to chlorosis through impacting chlorophyll synthesis and nitrogen metabolism in Areca catechu L. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 710093. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, G.R.; Sahoo, S. Role of iron in plant growth and metabolism. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2015, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Nozoye, T.; Nishizawa, N.K. Iron transport and its regulation in plants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, S.; Höller, S.; Meier, B.; Peiter, E. Manganese in plants: From acquisition to subcellular allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Scheffler, J. Genetic and molecular regulation of cotton fiber initiation and elongation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Araújo, É.; Ferreira Dos Santos, É.; Camacho, M.A. Boron-zinc interaction in the absorption of micronutrients by cotton. Agron. Colomb. 2018, 36, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y. Research on the Role of Micronutrient Management in Improving Cotton Fiber Quality. Cotton Genom. Genet. 2025, 16, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Millán, A.F.; Duy, D.; Philippar, K. Chloroplast iron transport proteins–function and impact on plant physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroh, G.E.; Pilon, M. Regulation of iron homeostasis and use in chloroplasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Yin, X. Nutrient Management in cotton. In Cotton Production; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.S.; Huyck, H.L. An overview of the abundance, relative mobility, bioavailability, and human toxicity of metals. In The Environmental Chemistry of Mineral Deposits, Reviews in Economic Geology; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moraghan, J.; Mascagni, H., Jr. Environmental and soil factors affecting micronutrient deficiencies and toxicities. Micronutr. Agric. 1991, 4, 371–425. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Júnior, J.P.; de Mello Prado, R.; Campos, C.N.S.; Oliveira, D.F.; Cazetta, J.O.; Detoni, J.A. Silicon foliar spraying in the reproductive stage of cotton plays an equivalent role to boron in increasing yield, and combined boron-silicon application, without polymerization, increases fiber quality. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 182, 114888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogiani, J.C.; Amaro, A.C.E.; Rosolem, C.A. Carbohydrate production and transport in cotton cultivars grown under boron deficiency. Sci. Agríc. 2013, 70, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Peng, J. Interaction between boron and other elements in plants. Genes 2023, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nie, K.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, M.; Yang, D.; Guan, X. The molecular mechanism of GhbHLH121 in response to iron deficiency in cotton seedlings. Plants 2023, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Morgan, P.W.; Joham, H.E.; Amin, J. Influence of substrate and tissue manganese on the IAA-oxidase system in cotton. Plant Physiol. 1968, 43, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawan, Z.M.; Mahmoud, M.H.; El-Guibali, A.H. Influence of potassium fertilization and foliar application of zinc and phosphorus on growth, yield components, yield and fiber properties of Egyptian cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.). J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Cui, C.; Muhammad Khan, N.; Zhou, G.; Wan, Y. Genome-wide investigation of ZINC-IRON PERMEASE (ZIP) genes in Areca catechu and potential roles of ZIPs in Fe and Zn uptake and transport. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1995647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Ahmad, F.; Abid, M.; Ullah, M.A. Impact of zinc fertilization on gas exchange characteristics and water use efficiency of cotton crop under arid environment. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Gwathmey, O.; Main, C.; Johnson, A. Effects of Sulfur Application Rates and Foliar Zinc Fertilization on Cotton Lint Yields and Qualities. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, S.; Ozkaya, I.; Caliskan, M.; Arslan, M. The effects of nitrogen and iron fertilization on growth, yield and fertilizer use efficiency of soybean in a Mediterranean-type soil. Field Crops Res. 2008, 108, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasim, M.; Akgür, Ö.; Yıldırım, B. An overview on boron and pollen germination, tube growth and development under in vitro and in vivo conditions. In Boron in Plants and Agriculture; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.Y.; Noaman, A.H. The role of boron in the vegetative growth characteristics of several cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) cultivars. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; p. 052056. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Oosterhuis, D.M. Cotton growth and physiological responses to boron deficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 2003, 26, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Gui, H.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Q.; Sikder, R.K.; Yang, G.; Song, M. Chemical defoliant promotes leaf abscission by altering ROS metabolism and photosynthetic efficiency in Gossypium hirsutum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Luo, Y.; Cao, N.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, W. Drought-induced cell wall degradation in the base of pedicel is associated with accelerated cotton square shedding. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallan, M.A.; Hassan, H.M.; Namich, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.A. Effect of sodium nitroprusside, putrescine and glycine betaine on alleviation of drought stress in cotton plant. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Mandal, S.K.; Bhaduri, S.; Armstrong, W.H. Manganese clusters with relevance to photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3981–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Xue, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals complex physiological response and gene regulation in peanut roots and leaves under manganese toxicity stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Dong, R.; Liu, P.; Liu, G.; Luo, L.; Chen, Z. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses reveal the roles of secondary metabolism in the adaptive responses of Stylosanthes to manganese toxicity. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, M. The Zn as a vital micronutrient in plants. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2021, 11, e4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, T.R.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Ghosh, P.K.; Sultana, S.; Das, A.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Keya, S.S.; Rahman, M.A. Zn Supplementation mitigates Drought effects on Cotton by improving photosynthetic performance and antioxidant defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, K. Lower and upper critical zinc levels in relation to cotton growth and development. Physiol. Plant. 1975, 35, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, K. Mn and B Effects on Micronutrients and P in Cotton 1. Agron. J. 1975, 67, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Hao, M. Impacts of long-term micronutrient fertilizer application on soil properties and micronutrient availability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, T.; Hakeem, K.R. Plant Micronutrients; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fan, H.; Song, Q.; Jing, L.; Yu, H.; Li, R.; Zhang, P.; Liu, F.; Li, W.; Sun, L. Physiological and molecular bases of the boron deficiency response in tomatoes. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Eaton-Rye, J.J.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Enhancing photosynthesis and plant productivity through genetic modification. Cells 2024, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wedegaertner, T. Genetics and breeding for glandless upland cotton with improved yield potential and disease resistance: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 753426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, F.; Aydın, A. An in-silico study: Interaction of BOR1-type boron (B) transporters with a small group of functionally unidentified proteins under various stresses in potato (Solanum tuberosum). Commagene J. Biol. 2020, 4, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Ye, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, F. Transcriptional Analysis Reveals the Differences in Response of Floral Buds to Boron Deficiency Between Two Contrasting Brassica napus Varieties. Plants 2025, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Maldonado, P.; Aquea, F.; Reyes-Díaz, M.; Cárcamo-Fincheira, P.; Soto-Cerda, B.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Inostroza-Blancheteau, C. Role of boron and its interaction with other elements in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1332459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Júnior, J.P.; de M Prado, R.; Campos, C.N.; Sousa Junior, G.S.; Oliveira, K.R.; Cazetta, J.O.; Gratão, P.L. Addition of silicon to boron foliar spray in cotton plants modulates the antioxidative system attenuating boron deficiency and toxicity. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, X.; Song, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W.; Riaz, M. Transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular mechanism of boron deficiency tolerance in leaves of boron-efficient Beta vulgaris seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 168, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, G.; Grotz, N.; Dédaldéchamp, F.; Gaymard, F.; Guerinot, M.L.; Briat, J.-F.; Curie, C. IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Wang, T. The adaptive mechanism of plants to iron deficiency via iron uptake, transport, and homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.; Yeh, K.-C. Role of root exudates in metal acquisition and tolerance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, K.; Nozoye, T.; Nagasaka, S.; Rasheed, S.; Miyauchi, N.; Seki, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Nishizawa, N.K. Paralogs and mutants show that one DMA synthase functions in iron homeostasis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Barranco, A.; Thomine, S.; Vert, G.; Zelazny, E. A quick journey into the diversity of iron uptake strategies in photosynthetic organisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1975088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.Y.; Li, C.X.; Sun, L.; Ren, J.Y.; Li, G.X.; Ding, Z.J.; Zheng, S.J. A WRKY transcription factor regulates Fe translocation under Fe deficiency. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E. Barley preferentially activates strategy-II iron uptake mechanism under iron deficiency. Biotech Stud. 2024, 33, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridis, G.; Chorianopoulou, S.N.; Ventouris, Y.E.; Sigalas, P.P.; Bouranis, D.L. An exploration of the roles of ferric iron chelation-strategy components in the leaves and roots of maize plants. Plants 2019, 8, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassarawa, I.S.; Li, Z.; Xue, L.; Li, H.; Muhammad, U.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhao, T. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate alleviate boron toxicity in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plants 2024, 13, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Geng, M.; Yuan, J.; Zhan, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, W.; Duan, H.; Zhao, H. GhRCD1 promotes cotton tolerance to cadmium by regulating the GhbHLH12–GhMYB44–GhHMA1 transcriptional cascade. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 1777–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomine, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant metal transporters with homology to proteins of the NRAMP family. In The NRAMP Family; Cellier, M., Gros, P., Eds.; Molecular Biology Intelligence Unit, Andes/Kluwer Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Verma, N.; Tewari, R.K. Micronutrient deficiency-induced oxidative stress in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotz, N.; Fox, T.; Connolly, E.; Park, W.; Guerinot, M.L.; Eide, D. Identification of a family of zinc transporter genes from Arabidopsis that respond to zinc deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7220–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, R.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, C.; Pu, M.; Lu, C.; Yang, Y.; Liang, G. bHLH121 functions as a direct link that facilitates the activation of FIT by bHLH IVc transcription factors for maintaining Fe homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasai, K.; Takano, J.; Miwa, K.; Toyoda, A.; Fujiwara, T. High boron-induced ubiquitination regulates vacuolar sorting of the BOR1 borate transporter in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 6175–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Smith, S.M.; Shabala, S.; Yu, M. Phytohormones in plant responses to boron deficiency and toxicity. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Araniti, F.; Bali, A.S.; Shahzad, B.; Tripathi, D.K.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Landi, M. The role of salicylic acid in plants exposed to heavy metals. Molecules 2020, 25, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.J.; Zhu, X.F.; Wang, Z.W.; Dong, F.; Dong, N.Y.; Zheng, S.J. Abscisic acid alleviates iron deficiency by promoting root iron reutilization and transport from root to shoot in A rabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Ueda, N.; Aoki, K.; Kuromori, T.; Hirayama, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaya, T.; Sakakibara, H. AtIPT3 is a key determinant of nitrate-dependent cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Jiang, B.; Wang, H.; Xiao, G. Gibberellic acid promotes single-celled fiber elongation through the activation of two signaling cascades in cotton. Dev. Cell 2024, 59, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, J.; Miwa, K.; Yuan, L.; von Wirén, N.; Fujiwara, T. Endocytosis and degradation of BOR1, a boron transporter of Arabidopsis thaliana, regulated by boron availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12276–12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Fontes, A.; Herrera-Rodríguez, M.; Martín-Rejano, E.M.; Navarro-Gochicoa, M.; Rexach, J.; Camacho-Cristóbal, J.J. Root responses to boron deficiency mediated by ethylene. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, J.; Wada, M.; Ludewig, U.; Schaaf, G.; von Wirén, N.; Fujiwara, T. The Arabidopsis major intrinsic protein NIP5; 1 is essential for efficient boron uptake and plant development under boron limitation. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, C.; Romera, F.J.; García, M.J.; Alcántara, E.; Pérez-Vicente, R. Ethylene participates in the regulation of Fe deficiency responses in Strategy I plants and in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.W.; Joham, H.E.; Amin, J. Effect of manganese toxicity on the indoleacetic acid oxidase system of cotton. Plant Physiol. 1966, 41, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero, V.; Ferreira Sánchez, D.; Abreu, I.; Sopeña-Torres, S.; Makarovsky-Saavedra, N.; Bernal, M.; Krämer, U.; Grolimund, D.; González-Guerrero, M.; Jordá, L. Arabidopsis thaliana Zn2+-efflux ATPases HMA2 and HMA4 are required for resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina BMM. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assunção, A.G.; Cakmak, I.; Clemens, S.; González-Guerrero, M.; Nawrocki, A.; Thomine, S. Micronutrient homeostasis in plants for more sustainable agriculture and healthier human nutrition. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, K. Manganese Nutrition of Cotton Under Two Boron Levels I. Growth and Development. Agron. J. 1973, 65, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Zhao, M.; Xue, Y. Transcriptome sequencing analysis of root in soybean responding to Mn poisoning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Maftoun, M.; Karimian, N.; Ronaghi, A.; Emam, Y. Effect of zinc× boron interaction on plant growth and tissue nutrient concentration of corn. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 30, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Schäfer, C.C.; Matthes, M.S. Molecular mechanisms affected by boron deficiency in root and shoot meristems of plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Cristóbal, J.J.; Martín-Rejano, E.M.; Herrera-Rodríguez, M.B.; Navarro-Gochicoa, M.T.; Rexach, J.; González-Fontes, A. Boron deficiency inhibits root cell elongation via an ethylene/auxin/ROS-dependent pathway in Arabidopsis seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3831–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, A.; Marshall-Colon, A.; Ronzier, E.; Szponarski, W.; Wang, R.; Gojon, A.; Crawford, N.M.; Ruffel, S.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Krouk, G. AtNIGT1/HRS1 integrates nitrate and phosphate signals at the Arabidopsis root tip. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Qamar, F.; Mehran, M.; Masood, S.; Shahzad, S.; Javed, M.; Azhar, M. Zinc nutrition optimization for better cotton productivity on alkaline calcareous soil. J. Cotton Res. 2025, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Abou-Baker, N. The contribution of nano-zinc to alleviate salinity stress on cotton plants. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-D.; Wu, Y.-J.; Ruan, X.-M.; Li, B.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Li, X.-B. Expressions of three cotton genes encoding the PIP proteins are regulated in root development and in response to stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Z. Engineered sulfur and iron nanoparticles enhance cotton tolerance to lead stress via distinct molecular and physiological strategies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.E.; Akcay, U.C. Overexpression of miR408 influences the cotton response to boron toxicity. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2024, 84, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordas, C. Foliar application of manganese increases seed yield and improves seed quality of cotton grown on calcareous soils. J. Plant Nutr. 2009, 32, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, M.; Xie, X. Cross-talks between macro-and micronutrient uptake and signaling in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamivand-Chegini, M.; Ebrahimie, E.; Tahmasebi, A.; Moghadam, A.; Eshghi, S.; Mohammadi-Dehchesmeh, M.; Kopriva, S.; Niazi, A. New insights into the evolution of SPX gene family from algae to legumes; a focus on soybean. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pireyre, M.; Burow, M. Regulation of MYB and bHLH transcription factors: A glance at the protein level. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhu, D.; Cui, J.; Liao, S.; Geng, M.; Zhou, W.; Hamilton, D. Plant availability of boron doped on iron and manganese oxides and its effect on soil acidosis. Geoderma 2009, 151, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.D.; Mei, L.; Ali, B.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, S. Cadmium-Induced Upregulation of Lipid Peroxidation and Reactive Oxygen Species Caused Physiological, Biochemical, and Ultrastructural Changes in Upland Cotton Seedlings. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 374063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabuayon, I.L.B.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Ritchie, G.L. High-throughput phenotyping in cotton: A review. J. Cotton Res. 2019, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, J.L.; Tsegaye, T.D.; Coleman, T.L.; Reddy, K.; Fahsi, A. Relationship between hyperspectral reflectance, soil nitrate-nitrogen, cotton leaf chlorophyll, and cotton yield: A step toward precision agriculture. J. Sustain. Agric. 2003, 22, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prananto, J.A.; Minasny, B.; Weaver, T. Rapid and cost-effective nutrient content analysis of cotton leaves using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). PeerJ 2021, 9, e11042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurtle-Schmidt, B.H.; Stroud, R.M. Structure of Bor1 supports an elevator transport mechanism for SLC4 anion exchangers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10542–10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Scheffler, B.E.; Bauer, P.J.; Campbell, B.T. Identification of the family of aquaporin genes and their expression in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, Y.; Kim, S.; Tsukamoto, T.; Oki, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Watanabe, S.; Matsuhashi, S.; Takahashi, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Mori, S. Mutational reconstructed ferric chelate reductase confers enhanced tolerance in rice to iron deficiency in calcareous soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7373–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Huang, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. The bHLH transcription factor PhbHLH121 regulates response to iron deficiency in Petunia hybrida. Plants 2024, 13, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaings, L.; Alcon, C.; Kosuth, T.; Correia, D.; Curie, C. Manganese triggers phosphorylation-mediated endocytosis of the Arabidopsis metal transporter NRAMP1. Plant J. 2021, 106, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |