The Role of Phosphorus-Potassium Nutrition in Synchronizing Flowering and Accelerating Generation Turnover in Sugar Beet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design and Nutritional Treatments

- (i)

- Deficiency (D): Irrigation with distilled water only (negative control)

- (ii)

- Knop’s solution (KS): Weekly application of 50 mL/plant of standard solution containing Ca(NO3)2 (1 g/L), MgSO4 (0.25 g/L), K2HPO4 (0.25 g/L), KCl (0.125 g/L), and FeSO4 (0.125 g/L), yielding final concentrations of N 170.8 mg/L, P 44.5 mg/L, K 112.2 mg/L (N:P:K = 3.8:1.0:4.0)

- (iii)

- Additional potassium (K): KS followed by 30 mL of KCl (12 g/L), resulting in total concentrations of N 170.8 mg/L, P 44.5 mg/L, K 2471.1 mg/L (N:P:K = 3.8:1.0:88.9)

- (iv)

- Additional phosphorus-potassium (PK): KS followed by 30 mL of KH2PO4 (40 g/L), yielding total concentrations of N 170.8 mg/L, P 3441.4 mg/L, K 4420.7 mg/L (N:P:K = 1.0:32.2:41.4)

2.3. Foliar Applications

2.4. Digital Phenotyping and Data Acquisition

2.5. Evaluation of Mini-Steckling Formation Under Different Light Regimes

2.6. Generative Development and Seed Production Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- 1.

- Initial linear mixed-effects models (LMM) were fitted with genotype, nutrition, time (as a numeric variable), and their two-way interactions as fixed effects, and plant identity as a random effect (random intercept).

- 2.

- Assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test on residuals) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s test) were formally assessed.

- 3.

- Where violations occurred, a systematic “rescue preprocessing” protocol was initiated: this included evaluating Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) with alternative distributions (gamma, log-normal, inverse Gaussian), applying normalizing transformations (log, square-root, Yeo-Johnson), and implementing enhanced outlier detection (e.g., residual-level winsorization).

- 4.

- The final model for each index was selected based on the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and successful fulfillment of parametric assumptions. This resulted in: a square-root transformed LMM with an AR(1) correlation structure for digital biomass; an untransformed LMM for NDVI; and a Yeo-Johnson transformed LMM for PSRI.

- 5.

- Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05) on estimated marginal means. As a robustness check, key findings were validated using non-parametric Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE).

3. Results

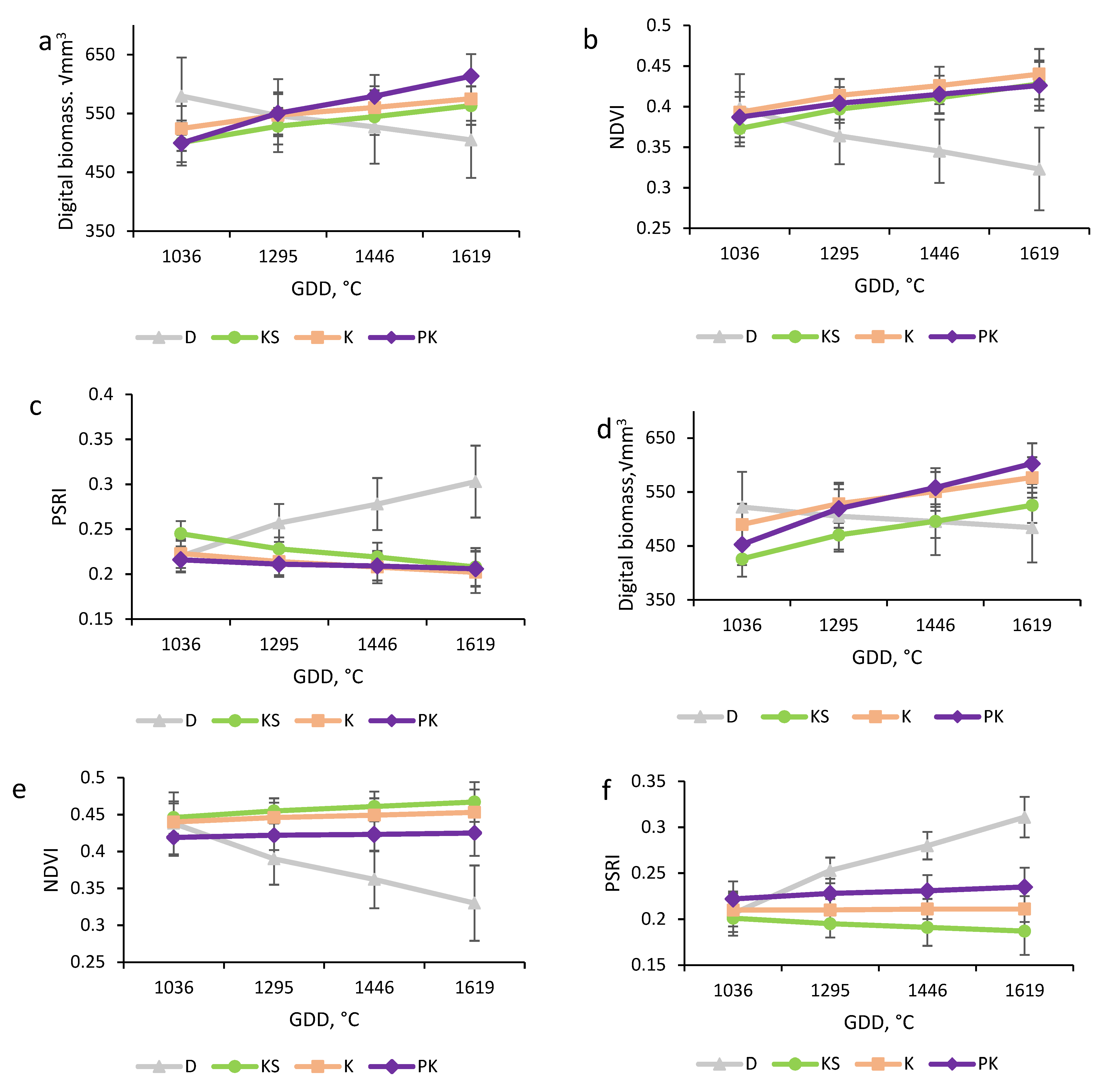

3.1. Digital Biomass Dynamics

3.2. Photosynthetic Performance and Plant Senescence (NDVI and PSRI)

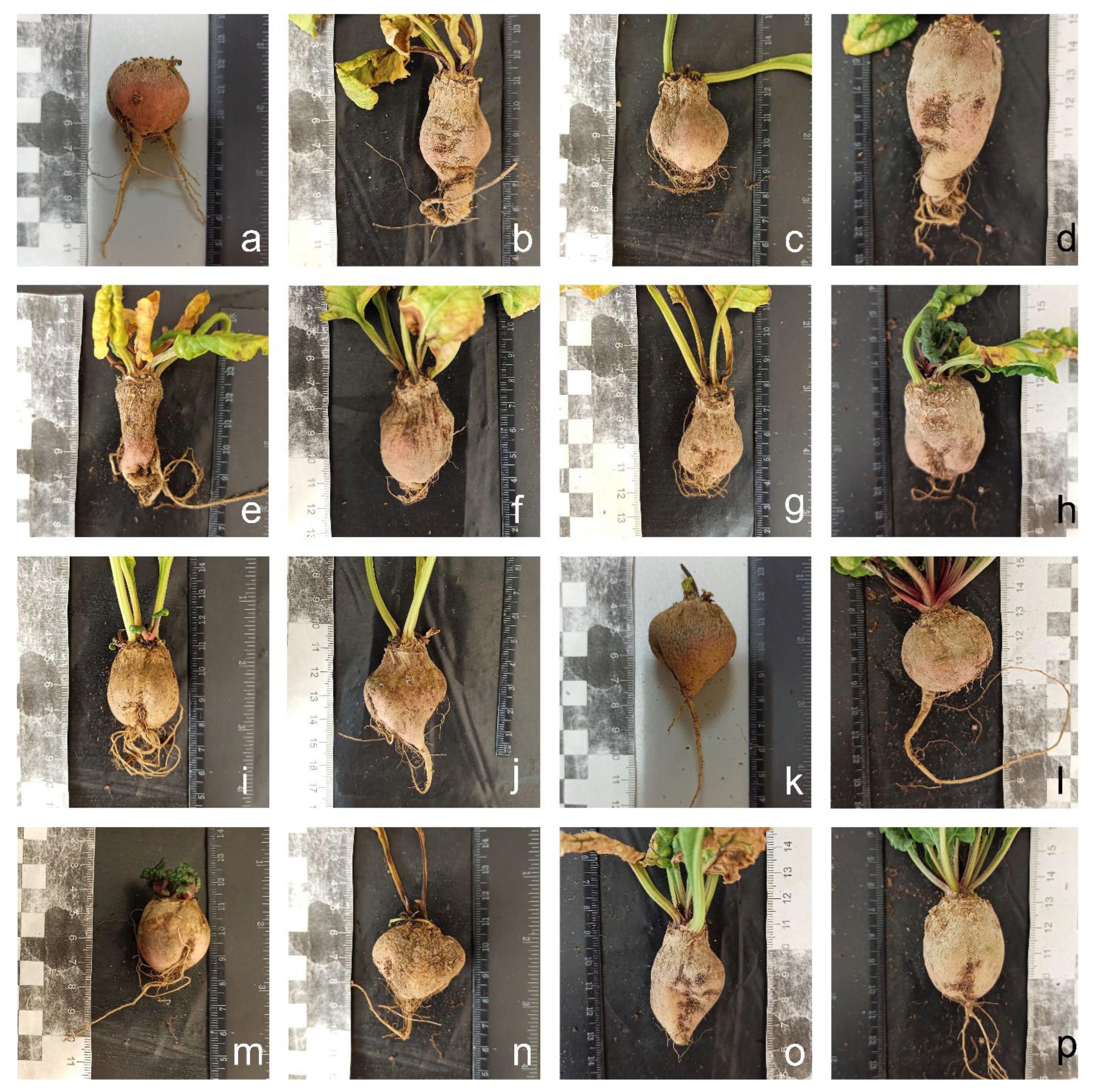

3.3. Influence of Mineral Nutrition on Mother Root (Mini-Steckling) Formation

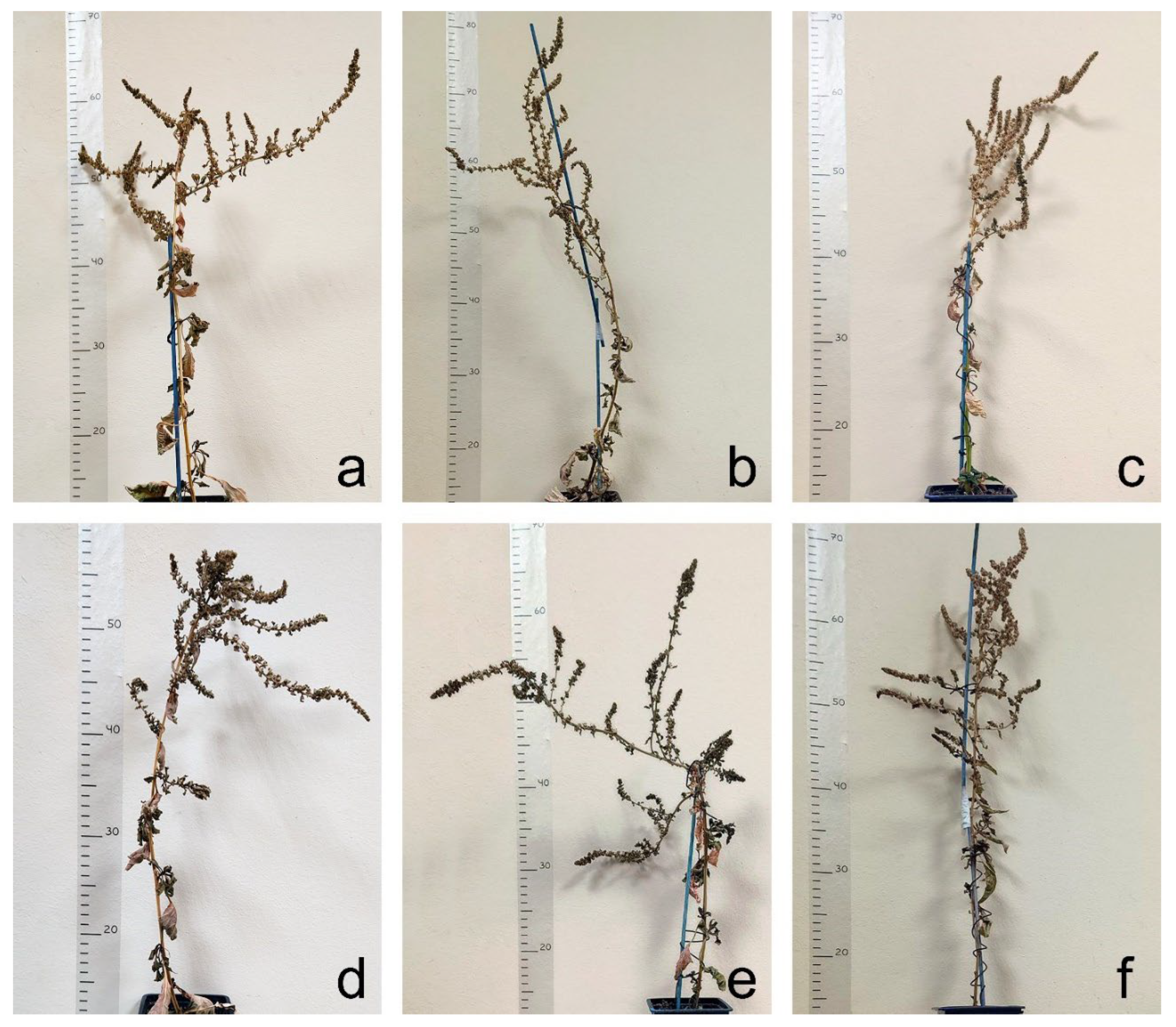

3.4. The Influence of Mineral Nutrition on Generative Development Following Vernalization

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implementation of PK Nutrition in Speed Breeding Systems

4.2. Genotype-Specific Responses and Breeding Applications

4.3. Nutritional Optimization and System Refinement

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Divashuk, M.G.; Blinkov, A.O.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Svistunova, N.Y.; Radzeniece, S.B.; Karlov, G.I. Practical Experience in Acceleration of Plant Development Under Controlled Growing Conditions. In Proceedings of the Plant Genetics, Genomics, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology (PlantGen 2023), Kazan, Russia, 10–15 July 2023; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Marenkova, A.G.; Blinkov, A.O.; Radzeniece, S.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Karlov, G.I.; Lavygina, V.A.; Patrushev, M.V.; Divashuk, M.G. Testing and Modification of the Protocol for Accelerated Growth of Malting Barley under Speed Breeding Conditions. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2024, 19, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Ghosh, S.; Williams, M.J.; Cuddy, W.S.; Simmonds, J.; Rey, M.-D.; Asyraf Md Hatta, M.; Hinchliffe, A.; Steed, A.; Reynolds, D.; et al. Speed Breeding Is a Powerful Tool to Accelerate Crop Research and Breeding. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Elwafa, S.F.; Abdel-Rahim, H.M.; Abou-Salama, A.M.; Teama, E.A. Sugar Beet Floral Induction and Fertility: Effect of Vernalization and Day-Length Extension. Sugar Tech 2006, 8, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Kuranouchi, T.; Okazaki, K.; Takahashi, H.; Taguchi, K. Biennial Sugar Beets Capable of Flowering without Vernalization Treatment. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 71, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggard, K.W.; Wickens, R.; Webb, D.J.; Scott, R.K. Effects of Sowing Date on Plant Establishment and Bolting and the Influence of These Factors on Yields of Sugar Beet. J. Agric. Sci. 1983, 101, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinkov, A.O.; Nagamova, V.M.; Minkova, Y.V.; Svistunova, N.Y.; Radzeniece, S.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Sleptsov, N.N.; Freymans, A.V.; Panchenko, V.V.; Chernook, A.G.; et al. A Higher Far-Red Intensity Promotes the Transition to Flowering in Triticale Grown under Speed Breeding Conditions. Vestn. VOGiS 2025, 29, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.G.; Dean, C. Arabidopsis, the Rosetta Stone of Flowering Time? Science 2002, 296, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, W.; Hou, K.; Wu, W. Bolting, an Important Process in Plant Development, Two Types in Plants. J. Plant Biol. 2019, 62, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.M. Breeding Biennial Crops. In Encyclopedia of Plant and Crop Science; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfeiler, J.; Alessandro, M.S.; Morales, A.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Galmarini, C.R. Vernalization Requirement, but Not Post-Vernalization Day Length, Conditions Flowering in Carrot (Daucus carota L.). Plants 2022, 11, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Deng, X.W. Phytochrome Signaling Mechanisms. Arab. Book 2011, 9, e0148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, G.F.J.; Jarvis, P.J.; Walters, C. A Vernalization-Intensity Model to Predict Bolting in Sugar Beet. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 148, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupin, P.Y.; Kroupina, A.Y.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. Root Causes of Flowering: Two Sides of Bolting in Sugar Beet. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggard, K.W.; Qi, A.; Armstrong, M.J. A Meta-Analysis of Sugarbeet Yield Responses to Nitrogen Fertilizer Measured in England Since 1980. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 147, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.M. Root Quality of Sugarbeet. Sugar Tech 2010, 12, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, D.; Nielsen, O.; Wilting, P.; Koch, H.-J.; Märländer, B. Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Fodder and Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) in Contrasting Environments of Northwestern Europe. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 73, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadoria, P.S.; Steingrobe, B.; Claassen, N.; Liebersbach, H. Phosphorus Efficiency of Wheat and Sugar Beet Seedlings Grown in Soils with Mainly Calcium, or Iron and Aluminium Phosphate. Plant Soil 2002, 246, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorassani, R.; Hettwer, U.; Ratzinger, A.; Steingrobe, B.; Karlovsky, P.; Claassen, N. Citramalic Acid and Salicylic Acid in Sugar Beet Root Exudates Solubilize Soil Phosphorus. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunin Yelets State University; Gulidova, V.; Zakharov, V. Bunin Yelets State University Productivity of Promising Sugar Beet Hybrids in the Lipetsk Region. VAGAU 2024, 235, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubravka KWS. Available online: https://www.kws.com/ru/ru/produkty/sakharnaya-svekla/obzor-gibridov/dubravka-kws/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Putilina, L.N.; Gribanova, N.P.; Lazutina, N.A. Complex Evaluation and Selection of Domestic Sugar Beet Breeding Material by Productivity and Technological Quality. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2021, 47, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Iberia KWS. Available online: https://www.kws.com/kz/ru/produkty/saharnaja-svekla/smart-iberia-kws/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Tsialtas, J.T.; Maslaris, N. The Effect of Temperature, Water Input and Length of Growing Season on Sugar Beet Yield in Five Locations in Greece. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 152, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabade, P.G.; Kumar, S.; Kohli, A.; Singh, U.M.; Sinha, P.; Singh, V.K. Speed Breeding 3.0: Mainstreaming Light-Driven Plant Breeding for Sustainable Genetic Gains. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 2462–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zewail, R.M.Y.; El-Gmal, I.S.; Khaitov, B.; El-Desouky, H.S.A. Micronutrients through Foliar Application Enhance Growth, Yield and Quality of Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.). J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, T.; Mahapatra, C.K.; Hosenuzzaman, M.; Gupta, D.R.; Hashem, A.; Avila-Quezada, G.D.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Hoque, M.A.; Paul, S.K. Zinc and Boron Soil Applications Affect Athelia Rolfsii Stress Response in Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, Z.; Sultana, R.; Parveen, R.; Swapnil; Singh, D.; Sinha, S.; Sahoo, J.P. Understanding the Concept of Speed Breeding in Crop Improvement: Opportunities and Challenges Towards Global Food Security. Trop. Plant Biol. 2024, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Páez, E.; Prohens, J.; Moreno-Cerveró, M.; De Luis-Margarit, A.; Díez, M.J.; Gramazio, P. Agronomic Treatments Combined with Embryo Rescue for Rapid Generation Advancement in Tomato Speed Breeding. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, A. Seed Production and Certification in Sugar Beet. In Sugar Beet Cultivation, Management and Processing; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Pin, P.A.; Benlloch, R.; Bonnet, D.; Wremerth-Weich, E.; Kraft, T.; Gielen, J.J.L.; Nilsson, O. An Antagonistic Pair of FT Homologs Mediates the Control of Flowering Time in Sugar Beet. Science 2010, 330, 1397–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Campagna, G.; Della Lucia, M.C.; Broccanello, C.; Bertoldo, G.; Chiodi, C.; Maretto, L.; Moro, M.; Eslami, A.S.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. SNP Alleles Associated with Low Bolting Tendency in Sugar Beet. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 693285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Choi, I.; Shahzad, Z.; Brandizzi, F.; Rouached, H. Nutrient Cues Control Flowering Time in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Kong, F.; Chen, L. Nutrient-Mediated Modulation of Flowering Time. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Okazaki, K.; Taguchi, K. Molecular Variation at BvBTC1 Is Associated with Bolting Tolerance in Japanese Sugar Beet. Euphytica 2019, 215, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Yao, Q.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Tan, W.; Wang, Q.; Xing, W.; Liu, D. Tolerance and Adaptation Characteristics of Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) to Low Nitrogen Supply. Plant Signal. Behav. 2023, 18, 2159155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozema, J.; Cornelisse, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Bruning, B.; Katschnig, D.; Broekman, R.; Ji, B.; Van Bodegom, P. Comparing Salt Tolerance of Beet Cultivars and Their Halophytic Ancestor: Consequences of Domestication and Breeding Programmes. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plu083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aallam, Y.; Dhiba, D.; El Rasafi, T.; Lemriss, S.; Haddioui, A.; Tarkka, M.; Hamdali, H. Growth Promotion and Protection against Root Rot of Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) by Two Rock Phosphate and Potassium Solubilizing Streptomyces spp. under Greenhouse Conditions. Plant Soil 2022, 472, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, L.; Yoon, J.; An, G. The Control of Flowering Time by Environmental Factors. Plant J. 2017, 90, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinkov, A.O.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Dmitrieva, A.R.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. Speed Breeding: Protocols, Application and Achievements. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1680955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M.; Brown, P.; Cakmak, I.; Rengel, Z.; Zhao, F. Function of Nutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 191–248. ISBN 978-0-12-384905-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.; Mahmud, J.; Hossen, M.; Masud, A.; Moumita; Fujita, M. Potassium: A Vital Regulator of Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Long, J.; Li, X.; Ke, L.; Xu, R.; Wu, Z.; Pi, Z. Vernalization Promotes Bolting in Sugar Beet by Inhibiting the Transcriptional Repressors of BvGI. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, N.; Xiao, K.; Holtgräwe, D.; Jung, C. The B2 Flowering Time Locus of Beet Encodes a Zinc Finger Transcription Factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10365–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | DAS (GDD, °C) | Genotype | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Iberia KWS | Dubravka KWS | ||||||||

| Treatment (Number of Plants) | |||||||||

| D (6) | KS (24) | K (18) | PK (18) | D (6) | KS (24) | K (18) | PK (18) | ||

| Digital biomass, √mm3 | 48 (1036) | 579.634 ab ± 65.531 | 500.651 b ± 33.204 | 524.605 ab ± 38.172 | 499.826 ab ± 38.172 | 522.139 ab ± 65.497 | 426.239 a ± 33.204 | 489.975 ab ± 38.172 | 452.820 ab ± 38.172 |

| 60 (1295) | 546.486 a ± 62.016 | 528.558 a ± 31.022 | 547.116 a ± 35.816 | 550.312 a ± 35.816 | 505.184 a ± 61.983 | 470.339 a ± 31.022 | 528.679 a ± 35.816 | 519.498 a ± 35.816 | |

| 67 (1446) | 527.150 a ± 62.263 | 544.837 a ± 31.176 | 560.248 a ± 35.982 | 579.762 a ± 35.982 | 495.293 a ± 62.231 | 496.064 a ± 31.176 | 551.257 a ± 35.982 | 558.394 a ± 35.982 | |

| 75 (1619) | 505.051 ab ± 64.619 | 563.442 ab ± 32.640 | 575.255 ab ± 37.563 | 613.418 ab ± 37.563 | 483.990 a ± 64.585 | 525.464 a ± 32.640 | 577.059 ab ± 37.563 | 602.846 b ± 37.563 | |

| NDVI | 48 (1036) | 0.398 ab ± 0.042 | 0.373 b ± 0.022 | 0.393 ab ± 0.025 | 0.387 ab ± 0.025 | 0.438 ab ± 0.042 | 0.446 a ± 0.022 | 0.440 ab ± 0.025 | 0.419 ab ± 0.025 |

| 60 (1295) | 0.364 ab ± 0.035 | 0.397 a ± 0.017 | 0.414 ab ± 0.020 | 0.404 ab ± 0.020 | 0.390 a ± 0.035 | 0.455 b ± 0.017 | 0.446 ab ± 0.020 | 0.422 ab ± 0.020 | |

| 67 (1446) | 0.345 acd ± 0.039 | 0.411 abdf ± 0.020 | 0.426 bef ± 0.023 | 0.415 abcdef ± 0.023 | 0.362 ab ± 0.039 | 0.461 ce ± 0.020 | 0.449 cdef ± 0.023 | 0.423 abcdef ± 0.023 | |

| 75 (1619) | 0.323 ac ± 0.051 | 0.428 bd ± 0.027 | 0.440 bd ± 0.031 | 0.426 bd ± 0.031 | 0.330 ab ± 0.051 | 0.467 cd ± 0.027 | 0.453 cd ± 0.031 | 0.425 cd ± 0.031 | |

| PSRI | 48 (1036) | 0.220 ab ± 0.017 | 0.245 b ± 0.014 | 0.223 ab ± 0.016 | 0.216 ab ± 0.014 | 0.206 ab ± 0.024 | 0.201 a ± 0.015 | 0.210 ab ± 0.018 | 0.222 ab ± 0.019 |

| 60 (1295) | 0.257 acd ± 0.021 | 0.228 abdf ± 0.013 | 0.214 bef ± 0.015 | 0.211 bef ± 0.014 | 0.253 ab ± 0.014 | 0.195 ce ± 0.015 | 0.210 cdef ± 0.012 | 0.228 abcdef ± 0.016 | |

| 67 (1446) | 0.278 acd ± 0.029 | 0.219 bef ± 0.016 | 0.208 bef ± 0.018 | 0.209 bef ± 0.016 | 0.280 ab ± 0.015 | 0.191 ce ± 0.020 | 0.211 cdef ± 0.011 | 0.231 df ± 0.017 | |

| 75 (1619) | 0.303 acd ± 0.040 | 0.208 bef ± 0.021 | 0.202 bef ± 0.023 | 0.206 bef ± 0.020 | 0.311 ab ± 0.022 | 0.187 ce ± 0.026 | 0.211 cdef ± 0.014 | 0.235 df ± 0.021 | |

| Treatment | Smart Iberia KWS | Dubravka KWS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Mineral Nutrition | Weight, g | Number of Plants | % vs. D | Weight, g | Number of Plants | % vs. D |

| W | D | 9.45 adf [7.82–11.08] | 2 | 0.0 | 11.11 abc [10.78–11.44] | 2 | 0.0 |

| KS | 15.18 beh [11.88–17.97] | 4 | 60.6 | 14.69 deg [13.77–15.68] | 4 | 32.2 | |

| K | 16.80 bceghi [13.58–20.02] | 2 | 77.8 | 16.34 defghi [15.68–17.01] | 2 | 47.1 | |

| PK | 24.85 cgi [24.81–24.89] | 2 | 163.0 | 16.14 fhi [12.60–19.68] | 2 | 45.3 | |

| FR | D | 6.02 adf [5.86–7.43] | 3 | 0.0 | 10.72 abc [9.33–10.82] | 3 | 0.0 |

| KS | 13.44 beh [11.43–16.24] | 6 | 123.3 | 10.89 deg [9.19–14.64] | 5 | 1.6 | |

| K | 9.51 bceghi [6.57–14.81] | 3 | 58.0 | 14.37 defghi [12.85–16.93] | 3 | 34.0 | |

| PK | 18.16 cgi [16.57–19.84] | 3 | 201.7 | 18.79 fhi [18.70–20.98] | 3 | 75.3 | |

| Smart Iberia KWS | Dubravka KWS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolting | ||||||||||

| Nutrition | N | Events | Censored | Censoring Rate | Median GDD | N | Events | Censored | Censoring Rate | Median GDD |

| D | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2295.42 abcdef | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2727.08 abcdef |

| KS | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2273.83 bf | 12 | 7 | 5 | 0.42 | 2403.33 acde |

| K | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2273.83 cef | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0.22 | 2424.92 abd |

| PK | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2317.00 de | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0.22 | 2424.92 abcf |

| Budding | ||||||||||

| D | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.67 | 3115.58 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.67 | 3115.58 |

| KS | 12 | 11 | 1 | 0.08 | 2489.67 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0.67 | 3115.58 |

| K | 9 | 8 | 1 | 0.11 | 2468.08 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 0.78 | 3115.58 |

| PK | 9 | 8 | 1 | 0.11 | 2489.67 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 0.67 | 3115.58 |

| Flowering | ||||||||||

| D | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3374.58 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3374.58 |

| KS | 12 | 6 | 6 | 0.5 | 3201.92 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 0.92 | 3374.58 |

| K | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0.33 | 2878.17 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 3374.58 |

| PK | 9 | 8 | 1 | 0.11 | 2878.17 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 3374.58 |

| Capsules | ||||||||||

| D | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3547.25 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3547.25 |

| KS | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0.58 | 3547.25 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 3547.25 |

| K | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0.33 | 3547.25 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 3547.25 |

| PK | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0.22 | 3547.25 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 0.78 | 3547.25 |

| Treatment (Genotype × Nutrition) | 1000-Seed Weight (g) | Seed Number per Plant | Seed Weight per Plant (g) | Flower Stalk Length (cm) | Flower Stalk Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dubravka KWS × KS | 14.71 a | 34.00 a | 0.50 a | 33.00 a [21.11–61.22] | 1.00 ac |

| Dubravka KWS × K | 26.61 a | 124.00 a | 3.30 a | 57.00 a | 38.00 ab |

| Dubravka KWS × PK | 20.86 a [19.55–24.74] | 374.00 a [194.00–404.00] | 7.80 a [4.80–7.90] | 63.00 a [63.00–71.00] | 33.00 bd [30.00–35.00] |

| Smart Iberia KWS × KS | 15.72 a [14.69–19.60] | 153.00 a [111.08–332.26] | 2.95 a [2.02–4.92] | 49.00 a [40.00–64.58] | 18.00 bd [9.50–22.83] |

| Smart Iberia KWS × K | 19.24 a [13.79–20.90] | 219.00 a [128.46–252.33] | 4.20 a [2.43–4.83] | 58.00 a [50.00–61.00] | 20.50 cd [17.00–21.83] |

| Smart Iberia KWS × PK | 21.36 a [18.83–22.21] | 192.00 a [116.39–210.87] | 4.10 a [2.49–4.47] | 57.50 a [55.62–60.50] | 21.00 ac [19.25–24.62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kroupina, A.Y.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Polyakova, M.N.; Alkubesi, M.; Ulyanova, A.A.; Ulyanov, D.S.; Svistunova, N.Y.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. The Role of Phosphorus-Potassium Nutrition in Synchronizing Flowering and Accelerating Generation Turnover in Sugar Beet. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2026, 17, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010005

Kroupina AY, Kroupin PY, Polyakova MN, Alkubesi M, Ulyanova AA, Ulyanov DS, Svistunova NY, Kocheshkova AA, Karlov GI, Divashuk MG. The Role of Phosphorus-Potassium Nutrition in Synchronizing Flowering and Accelerating Generation Turnover in Sugar Beet. International Journal of Plant Biology. 2026; 17(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleKroupina, Aleksandra Yu., Pavel Yu. Kroupin, Mariya N. Polyakova, Malak Alkubesi, Alana A. Ulyanova, Daniil S. Ulyanov, Natalya Yu. Svistunova, Alina A. Kocheshkova, Gennady I. Karlov, and Mikhail G. Divashuk. 2026. "The Role of Phosphorus-Potassium Nutrition in Synchronizing Flowering and Accelerating Generation Turnover in Sugar Beet" International Journal of Plant Biology 17, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010005

APA StyleKroupina, A. Y., Kroupin, P. Y., Polyakova, M. N., Alkubesi, M., Ulyanova, A. A., Ulyanov, D. S., Svistunova, N. Y., Kocheshkova, A. A., Karlov, G. I., & Divashuk, M. G. (2026). The Role of Phosphorus-Potassium Nutrition in Synchronizing Flowering and Accelerating Generation Turnover in Sugar Beet. International Journal of Plant Biology, 17(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb17010005