Beyond the Wood Log: Relationships Among Bark Anatomy, Stem Diameter, and Tolerance to Eucalypt Physiological Disorder (EPD) in Cultivated Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex Maiden and E. urophylla T. Blake

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

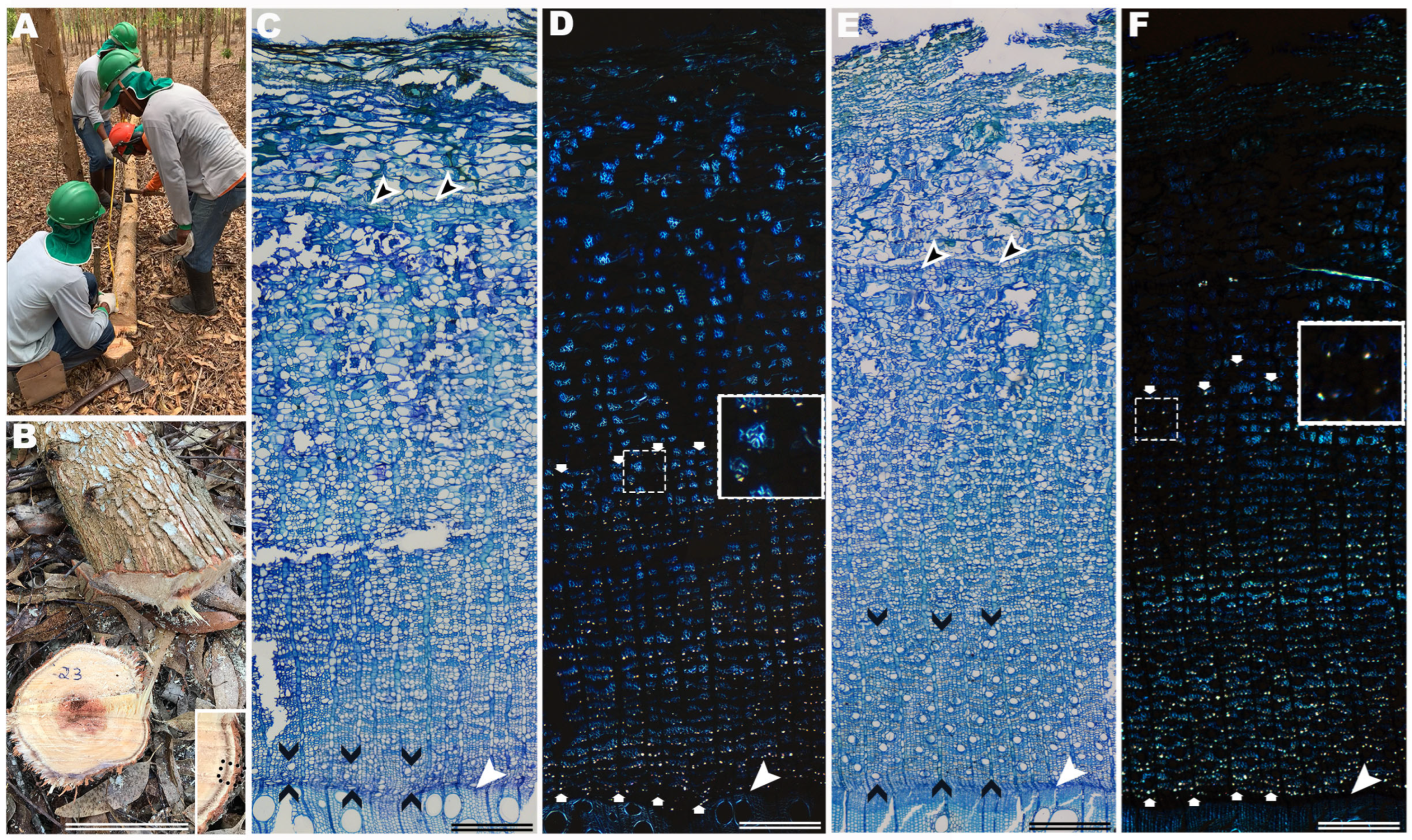

2.1. Experiment

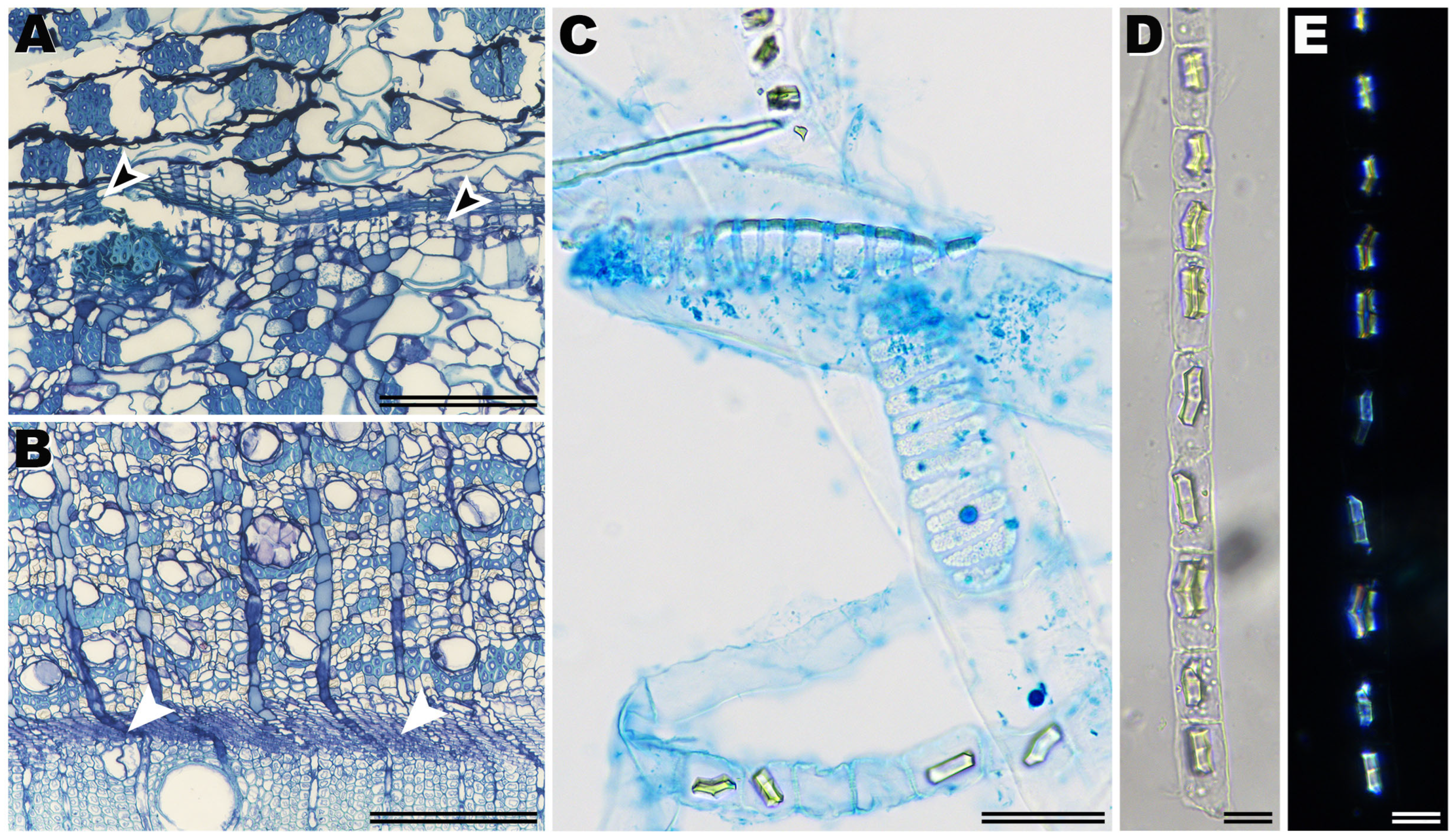

2.2. Sample Processing

2.3. Analysis of Bark Variation and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Correlation Analysis

2.6. Kohonen Self-Organizing Maps (SOM)

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics Preliminary Analysis

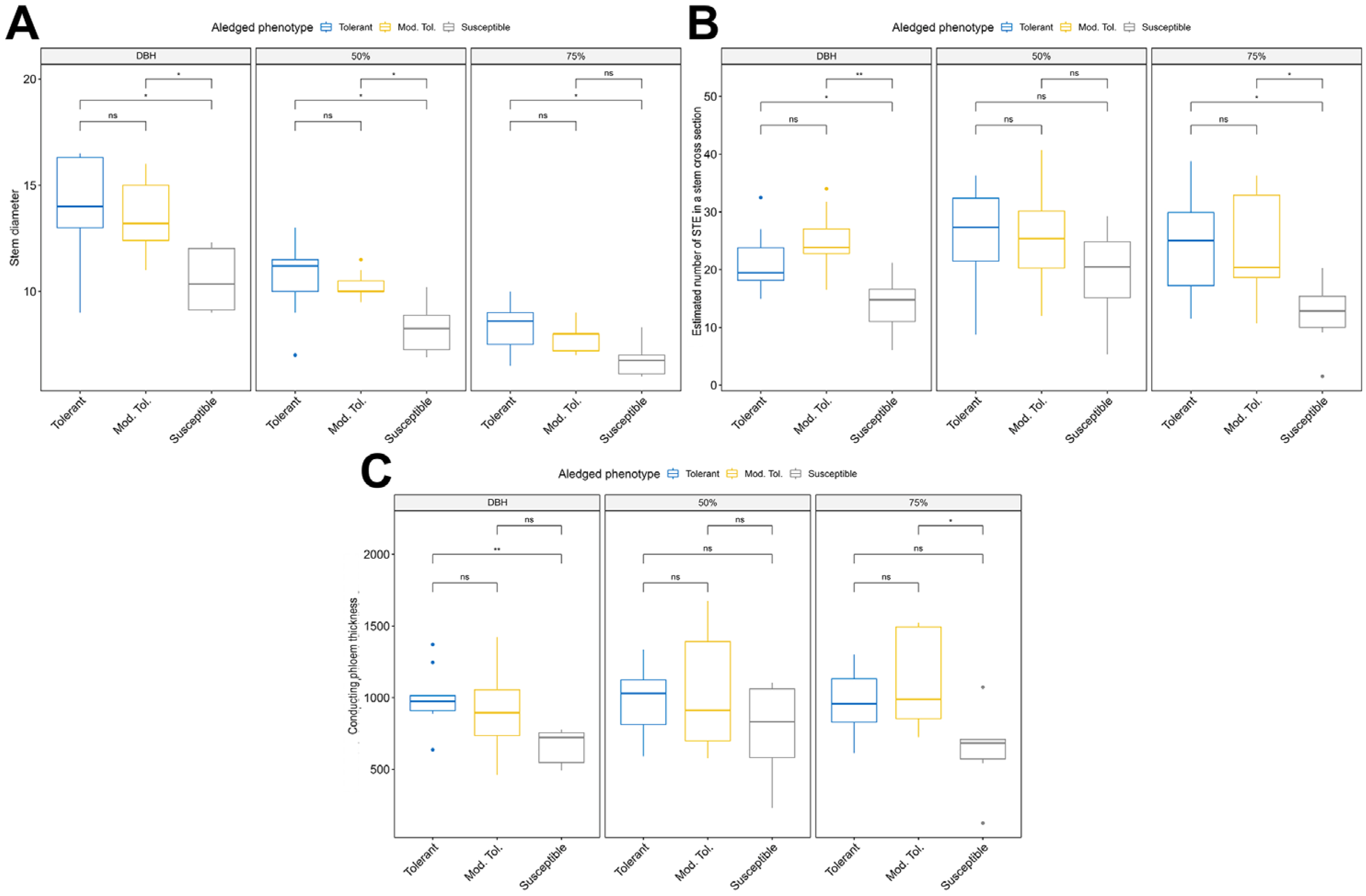

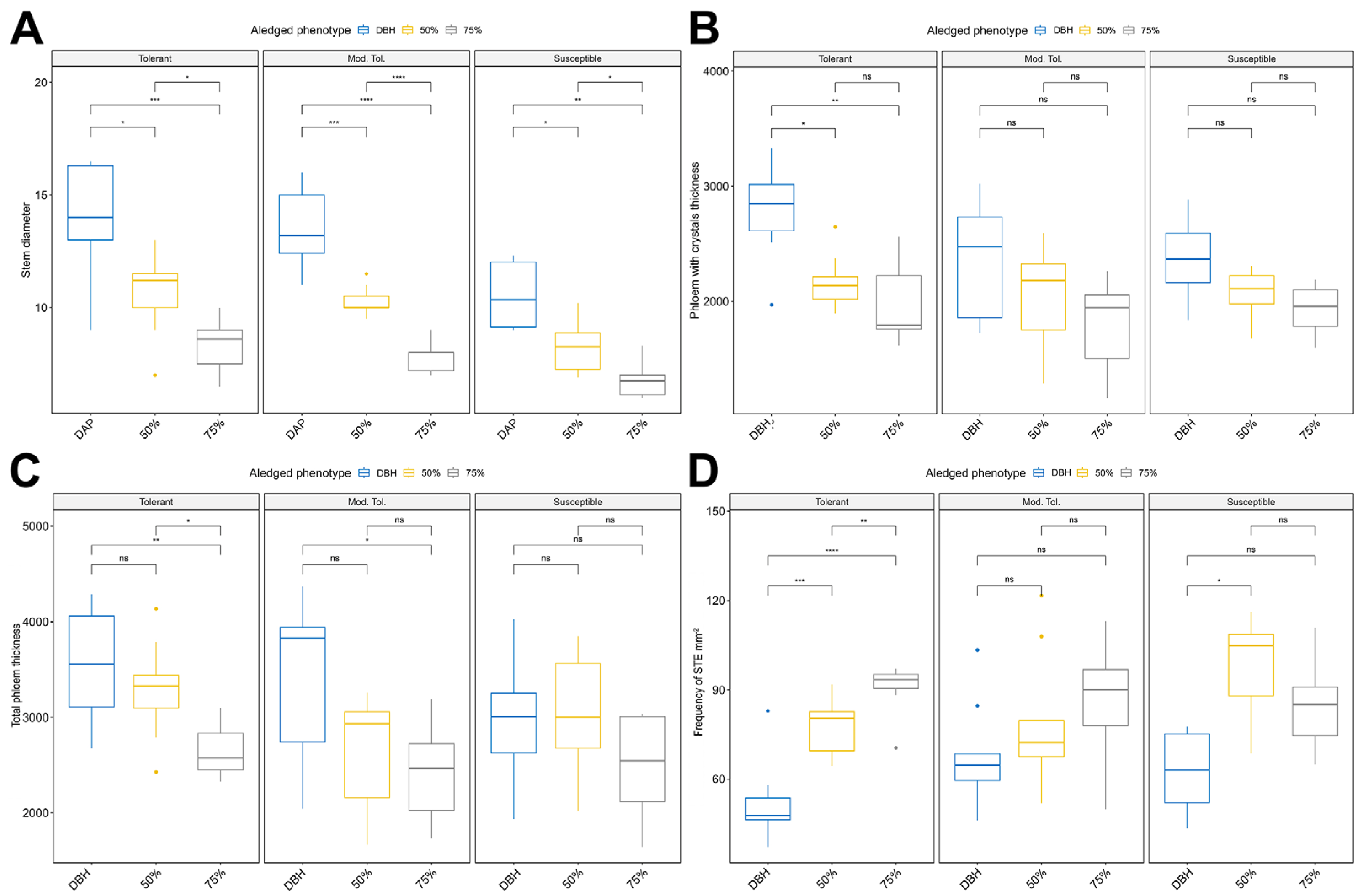

3.2. Analysis of Variance and Comparison Between Means

3.3. Correlation Analysis

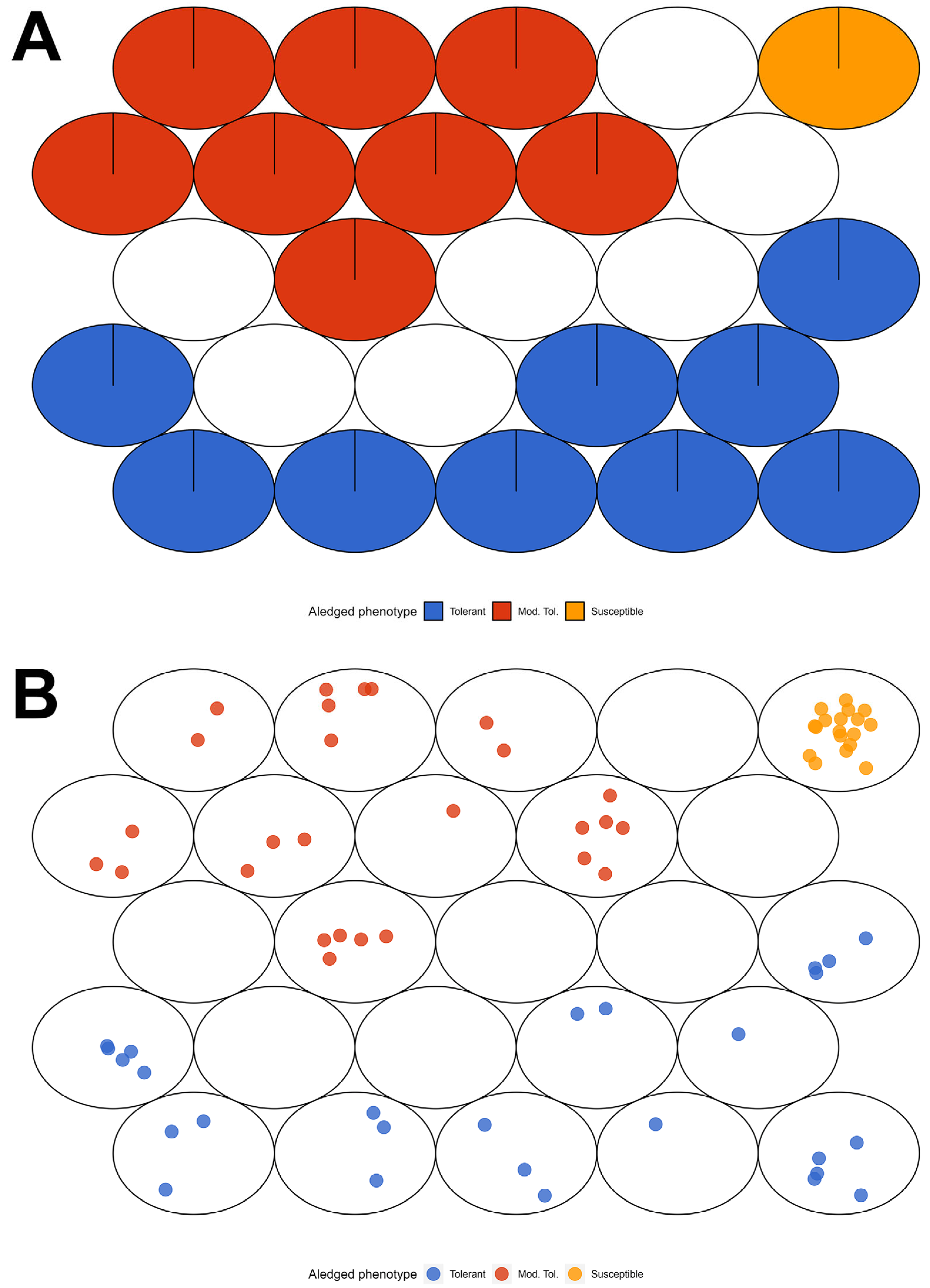

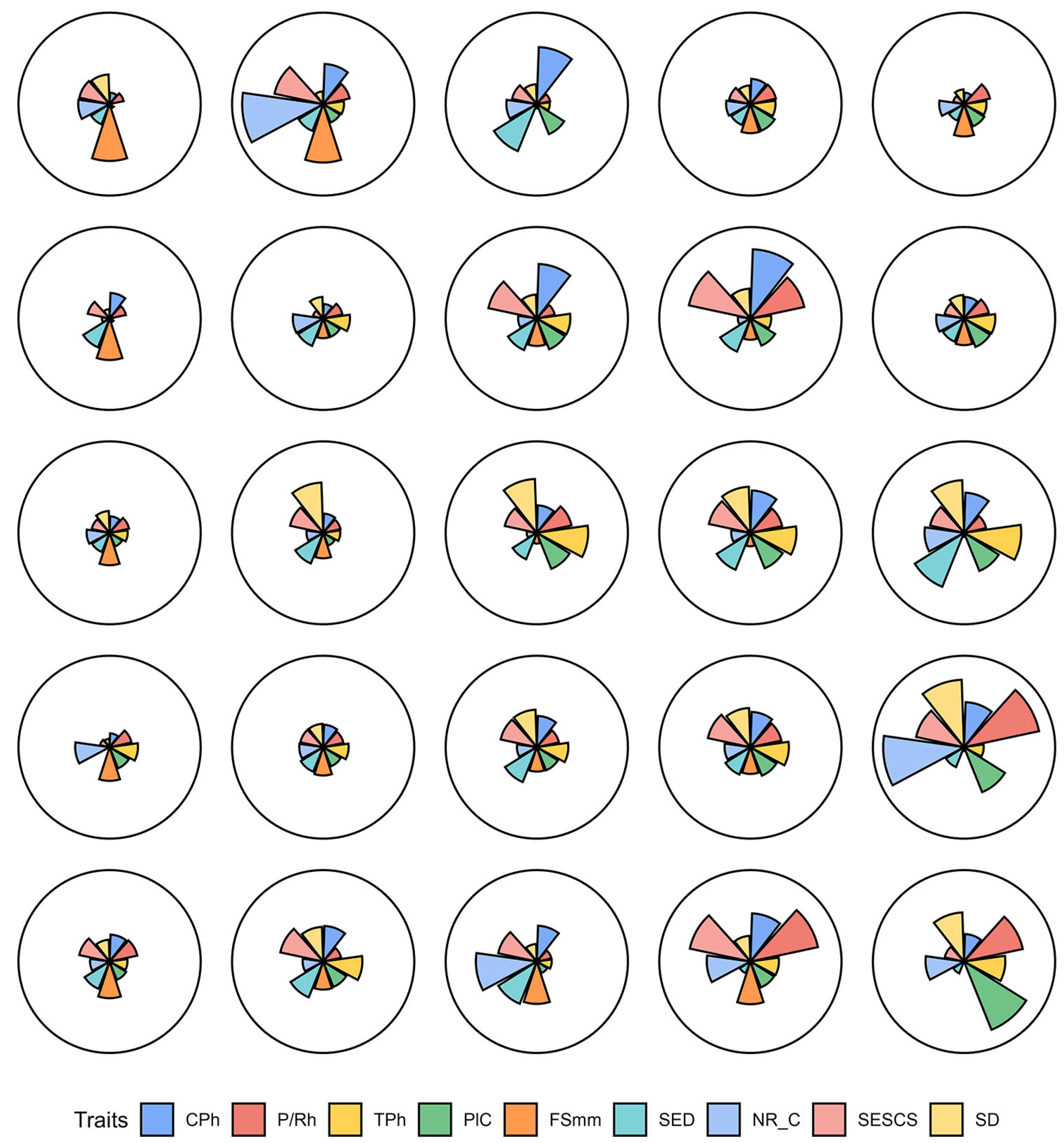

3.4. Pattern Recognition (SOM)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPD | Eucalypt Physiological Disorder |

| CaOx | Calcium oxalate crystals |

| STE | sieve tube element |

| DBH | Diameter at the Breast Hight |

| Btt | bark total thickness |

| P/Rh | periderm or rhytidome thickness |

| TPh | total phloem tissue thickness |

| CPh | conducting phloem thickness |

| PIC | thickness of phloem with crystals |

| NCoP | thickness of nonconducting phloem |

| CPPC/2 | average thickness of conducting and phloem with crystals |

| SED | average diameter of sieve tube elements |

| CPA | estimated fraction of conducting phloem in stem cross section |

| TPCA | estimated area of total phloem tissue in stem cross section |

| NR_C | number of parenchyma rays per 100 µm |

| PIC/Pl | ratio of phloem with crystals thickness per total phloem thickness |

| CPh/Pl | ratio of conducting phloem per total phloem thickness |

| SESCS | estimated number of sieve tube element per stem cross section |

| FSmm | frequency of sieve tube element per mm2 |

| SOM | Kohonen Self-Organizing Map |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Brooker, M.I.H.; Kleinig, D.A. Field Guide to Eucalypts, 3rd ed.; Volume 1. South Eastern Australia; Inkata Press Pty Ltd.: Mount Waverley, Australia, 2006; 356p. [Google Scholar]

- ABARES. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences. Australian Forest Profiles: Eucalypt; Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.S.; Chen, L.W.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Tahir, P.M. Engineering Wood Products from Eucalyptus spp. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8000780. [Google Scholar]

- INDÚSTRIA BRASILEIRA DE ÁRVORES Relatório Anual IBÁ 2023. Available online: https://iba.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/relatorio-anual-iba2023-r.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Laclau, J.-P.; Mignard, E.; Bouvet, J.-M.; Mareschal, L. (Eds.) Eucalyptus 2018: Managing Eucalyptus Plantations Under Global Changes; Abstracts Book, Montpellier, France (17–21 September 2018); IUFRO: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, L.L.; Fontaine, J.B.; Ruthrof, K.X.; Matusick, J.; Harper, R.J.; Hardy, G.E.S.J. Carbon consequences of drought differ in forests that resprout. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.N.F.; Vidaurre, G.B.; Pezzopane, J.E.M.; Lousada, J.L.P.C.; Silva, M.E.C.M.; Câmara, A.P.; Rocha, S.M.G.; Oliveira, J.C.L.; Campoe, O.C.; Carneiro, R.L.; et al. Heartwood variation of Eucalyptus urophylla is influenced by climatic Conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, A.P.; Vidaurre, G.B.; Oliveira, J.C.L.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Almeida, M.A.F.; Roque, R.M.; Tomazello Filho, M.; Souza, H.J.P.; Oliveira, T.R.; Campoe, O.C. Changes in hydraulic architecture across a water availability gradient for two contrasting commercial Eucalyptus clones. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 474, 118380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florêncio, G.W.L.; Martins, F.B.; Fagundes, F.F.A. Climate change on Eucalyptus plantations and adaptive measures for sustainable forestry development across Brazil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.C.R. Weather, Eucalyptus Dieback in New England, and a General Hypothesis of the Cause of Dieback. Pakc. Sci. 1986, 40, 58–78. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/1005 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Mueller-Dombois, D. Perspectives for an etiology of stand-level dieback. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1986, 17, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensham, R.J.; Holman, J.E. Temporal and spatial patterns in drought-related tree dieback in Australian savanna. J. Appl. Ecol. 1999, 36, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Jurskis, V. Eucalypt decline in Australia, and a general concept of tree decline and dieback. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 215, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusick, G.; Ruthrof, K.X.; Hardy, G.S.J. Drought and heat triggers sudden and severe dieback in a dominant mediterranean-type woodland species. Open J. For. 2012, 2, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartllori, E.; Lloret, F.; Aakala, T.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Aynekulu, E.; Bendixsen, D.P.; Bentouati, A.; Bigler, C.; Burk, C.J.; Camarero, J.J.; et al. Forest and woodland replacement patterns following drought-related mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 29720–29729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerga, B.; Warkineh, B.; Teketay, D.; Woldetsadik, M. The sustainability of reforesting landscapes with exotic species: A case study of eucalypts in Ethiopia. Sustain. Earth 2021, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P.L.d.; Pimenta, A.S.; Miranda, N.d.O.; Melo, R.R.d.; Amorim, J.d.S.; Azevedo, T.K.B.d. The Myth That Eucalyptus Trees Deplete Soil Water—A Review. Forests 2025, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C. New Introductions–Doing It Right. In Developing a Eucalypt Resource: Learning from Australia and Elsewhere: University of Canterbury; Wood Technology Research Centre: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2011; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stanturf, J.A.; Vance, E.D.; Fox, T.R.; Kirst, M. Eucalyptus beyond its native range: Environmental issues in exotic bioenergy plantations. Int. J. For. Res. 2013, 2013, 463030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoli, E.A.T.; de Resende, M.D.V.; Oda, S. Come Hell or High Water: Breeding the Profile of Eucalyptus Tolerance to Abiotic Stress Focusing Water Deficit. In Plant Growth and Stress Physiology; Gupta, D.K., Palma, J.M., Eds.; Plant in Challenging Environments; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 91–127. [Google Scholar]

- Alfenas, A.C.; Zauza, E.A.V.; Mafia, R.G.; de Assis, T.F. Clonagem e Doenças do Eucalipto, 2nd ed.; UFV Press: Viçosa, Brazil, 2009; 500p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, B.P.; da Silva Oliveira, J.T.; Demuner, B.J.; Mafia, R.G.; Vidaurre, G.B. Chemical and Kraft Pulping Properties of Young Eucalypt Trees Affected by Physiological Disorders. Forests 2022, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilhó, T.; Pereira, H.; Richter, H.G. Variability of bark structure in plantation-grown Eucalyptus globulus. IAWA J. 1999, 20, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, F.; Quilhó, T.; Pereira, H. Variability of fiber length in wood and bark in Eucalyptus globulus. IAWA J. 2000, 21, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I.; Gominho, J.; Mirra, I.; Pereira, H. Fractioning and chemical characterization of barks of Betula pendula and Eucalyptus globulus. Ind. Crop Prod. 2013, 41, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I.; Lima, L.; Quilhó, T.; Knapic, S.; Pereira, H. The bark of Eucalyptus sideroxylon as a source of phenolic extracts with anti-oxidant properties. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016, 82, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, A.P.; Oliveira, J.T.S.; Bobadilha, G.S.; Vidaurre, G.B.; Tomazello Filho, M.; Soliman, E.P. Physiological disorders affecting dendrometric parameters and Eucalyptus wood quality for pulping wood. Cerne 2018, 24, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.N.F.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Moulin, J.C.; Guimarães, L.M.S.; Zauza, E.A.V.; Loos, R.A.; Hall, K.B.; Gomes, D.S.; Conceição, G.J.; Rodrigues, P.D.; et al. Propriedades da madeira como potenciais biomarcadores de tolerância a distúrbios fisiológicos: Comparação de genótipos de eucalipto divergentes. Sci. For. 2020, 50, e3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.R.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Souza, G.A.; Condé, S.A.; Silva, N.M.; Lopes-Matos, K.L.; Resende, M.D.V.; Zauza, E.A.V.; Oda, S. Phenotypic markers in early selection for tolerance to dieback in Eucalyptus. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017, 107, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.N.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Souza, G.A.; Farag, M.A.; Scotti, M.T.; Barbosa Filho, J.M.; da Silva, M.S.; Tavares, J.F. Phenolics metabolism provides a tool for screening drought tolerant Eucalyptus grandis hybrids. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2017, 11, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Bueno, I.G.; Picoli, E.A.T.; dos Santos Isaias, R.M.; Lopes-Mattos, K.L.B.; Cruz, C.D.; Kuki, K.N.; Zauza, E.A.V. Wood anatomy of field grown eucalypt genotypes exhibiting differential dieback and water deficit tolerance. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Madeira, D.D.; Omena-Garcia, R.P.; Elerati, T.L.; da Silva Lopes, C.B.; Corrêa, T.R.; de Souza, G.A.; Oliveira, L.A.; Cruz, C.D.; Bhering, L.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; et al. Metabolic, Nutritional and Morphophysiological Behavior of Eucalypt Genotypes Differing in Dieback Resistance in Field When Submitted to PEG-Induced Water Deficit. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.R.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Pereira, W.L.; Condé, A.S.; Resende, R.T.; de Resende, M.D.V.; da Costa, W.G.; Cruz, C.D.; Zauza, E.A.V. Very early biomarkers screening for water deficit tolerance in commercial Eucalyptus clones. Agronomy 2023, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.L.; Aguiar, V.P.; Jacomini, F.A.; Costa, E.G.; Ribeiro, W.S.; Domokos-Szabolcsy, E.; Kleine, A.A.; Balmant, K.M.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Zauza, E.A.V.; et al. Rapid detection of bromatological and chemical biomarkers of clones tolerant to eucalyptus physiological disorder. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 175, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiello, E.M.; Ruiz, H.A.; Silva, I.R.; Barros, N.F.; Neves, J.C.L.; Behling, M. Transporte de boro no solo e sua absorção por eucalipto. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2009, 33, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leite, F.P.; Novais, R.F.; Silva, I.R.; Barros, N.F.; Neves, J.C.L.; Medeiros, A.G.B.; Ventrella, M.C.; Villani, E.M.A. Manganese accumulation and its relation to “eucalyptus shoot blight in the Vale do Rio Doce”. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2014, 38, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, S.A.; Picoli, E.A.T.; Corrêa, T.R.; dos Santos Dias, L.A.; Lourenço, R.D.S.; dos Santos Silva, F.C.; Pereira, W.L.; Zauza, E.A.V. Biomarkers for early selection in eucalyptus tolerant to dieback associated with water deficit. Rer. Bras. Ciênc. Agrár. 2020, 15, e7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.C.; Pereira, M.R.R.; Lopes, M.T.G. Germinação de sementes de eucalipto sob estresse hídrico e salino. Biosci. J. 2014, 30, 318–329. [Google Scholar]

- Rawal, D.S.; Kasel, S.; Keatley, M.R.; Nitschke, C.R. Climatic and photoperiodic effects 825 on flowering phenology of select eucalypts from south-eastern Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214/215, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strock, C.F.; Schneider, H.M.; Lynch, J.P. Anatomics: High-throughput phenotyping of plant anatomy. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandani, Y.; Sarikhani, H.; Gholami, M.; Ramandi, H.D.; Rad, A.C. Screening of Drought-tolerant Grape Cultivars Using Multivariate Discrimination Based on Physiological, Biochemical and Anatomical Traits. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.A. Bark in Woody Plants: Understanding the Diversity of a Multifunctional Structure. Integr Comp. Biol. 2019, 59, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfautsch, S. Hydraulic anatomy and function of trees—Basics and critical developments. Curr. For. Rep. 2016, 2, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.E.L.; Santos, R.C.; Vidaurreb, G.B.; Castro, R.V.O.; Rocha, S.M.G.; Carneiro, R.L.; Campoe, O.C.; Santos, C.P.S.; Gomes, I.R.F.; Carvalho, N.F.O.; et al. The effects of contrasting environments on the basic density and mean annual increment of wood from eucalyptus clones. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.M.L. Características Morfofisiológicas Associadas à Restrição Hídrica em Clones de Eucalipto. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2013; 26p. [Google Scholar]

- Liesche, J.; Pace, M.R.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, S. Height-related scaling of phloem anatomy and the evolution of sieve element end wall types in woody plants. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clair, B.; Ghislain, B.; Prunier, J.; Lehnebach, R.; Beauchêne, J.; Alméras, T. Mechanical contribution of secondary phloem to postural control in trees: The bark side of the force. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Salmerón, V.; Cho, H.; Tonn, N.; Greb, T. The Phloem as a Mediator of Plant Growth Plasticity. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R173–R181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, Y.; Dietrich, L.; Sevanto, S.; Hölttä, T.; Dannoura, M.; Epron, D. Drought impacts on tree phloem: From cell-level responses to ecological significance. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannoura, M.; Epron, D.; Desalme, D.; Massonnet, C.; Tsuji, S.; Plain, C.; Priault, P.; Gérant, D. The impact of prolonged drought on phloem anatomy and phloem transport in young beech trees. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gričar, J.; Jevšenak, J.; Giagli, K.; Eler, K.; Tsalagkas, D.; Gryc, V.; Vavrčík, H.; Čufar, K.; Prislan, P. Temporal and spatial variability of phloem structure in Picea abies and Fagus sylvatica and its link to climate. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 1285–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevanto, S. Phloem transport and drought. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelli-Feltrin, R.; Smith, A.M.S.; Adams, H.D.; Thompson, R.A.; Kolden, C.A.; Yedinak, K.M.; Johnson, D.M. Death from hunger or thirst? Phloem death, rather than xylem hydraulic failure, as a driver of fire-induced conifer mortality. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, C.J.; Mota, G.S.; Mori, F.A.; Miranda, I.; Quilhó, T.; Pereira, H. Bark characterization of a commercial Eucalyptus urophylla hybrid clone in view of its potential use as a biorefinery raw material. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2022, 12, 1541–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.P.; Feder, N.; McCully, M.E. Polychromatic staining of plant cell walls by toluidine blue O. Protoplasma 1964, 59, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angyalossy, V.; Pace, M.R.; Evert, R.F.; Marcati, C.R.; Oskolski, A.A.; Terrazas, T.; Kotina, E.; Lens, F.; Mazzoni-Viveiros, S.C.; Angeles, G.; et al. IAWA List of Microscopic Bark Features. IAWA J. 2016, 37, 517–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Version 3.6.1). Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses (R Package Version 1.0.7). 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/index.html (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Barbosa, I.P.; da Costa, W.G.; Nascimento, M.; Cruz, C.D.; de Oliveira, A.C.B. Recommendation of Coffea arabica genotypes by factor analysis. Euphytica 2019, 215, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.D.; Nascimento, M. Inteligência Computacional Aplicada ao Melhoramento Genético; Editora UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2018; 414p. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, W.G.; Barbosa, I.P.; de Souza, J.E.; Cruz, C.D.; Nascimento, M.; de Oliveira, A.C.B. Machine learning and statistics to qualify environments through multi-traits in Coffea arabica. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesolowski, A.; Adams, M.; Pfautsch, S. Insulation capacity of three bark types of temperate Eucalyptus species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 313, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, D.W.; Luo, A. Quantifying tree and forest bark structure with a bark-fissure index. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.A.; Gleason, S.; Méndez-Alonzo, R.; Chang, Y.; Westoby, M. Bark functional ecology: Evidence for tradeoffs, functional coordination, and environment producing bark diversity. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, F.M.G.; Pimenta, E.M.; Goulart, C.P.; De Almeida, M.N.F.; Vidaurre, G.B.; Hein, P.R.G. Effect of stand density on longitudinal variation of wood and bark growth in fast-growing Eucalyptus plantations. iForest 2019, 12, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gričar, J.; Prislan, P. Seasonal changes in the width and structure of non-collapsed phloem affect the assessment of its potential conducting efficiency. IAWA J. 2022, 43, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Gianoli, E.; Gómez, J.M. Ecological limits to plant phenotypic plasticity. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.A.; Olson, M.E.; Anfodillo, T.; Martínez-Méndez, N. Exploring the bark thickness-stem diameter relationship: Clues from lianas, successive cambia, monocots and gymnosperms. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Segovia, K.; Olson, M.E.; Campo, J.; Ángeles, G.; Martínez-Garza, C.; Vetter, S.; Rosell, J.A. Tip-to-base bark cross-sectional areas contribute to understanding the drivers of carbon allocation to bark and the functional roles of bark tissues. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harguindeguy, I.; Castro, G.F.; Novais, S.V.; Vergutz, L.; Araujo, W.L.; Novais, R.F. Physiological responses to hypoxia and manganese in Eucalyptus clones with differential tolerance to Vale do Rio Doce shoot dieback. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2018, 42, e0160550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J. Drought and dieback of rural eucalypts. Aust. J. Ecol. 1985, 10, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Blackman, C.J.; Rymer, P.D.; Quintans, D.; Duursma, R.A.; Choat, B.; Medlyn, B.E.; Tissue, D.T. Xylem embolism measured retrospectively is linked to canopy dieback in natural populations of Eucalyptus piperita following drought. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matusick, G.; Ruthrof, K.X.; Hardy, G.E.S.J. Stem functional traits vary among co-occurring tree species and forest vulnerability to drought. Aust. J. Bot. 2022, 70, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, O.M.M.; Collicchio, E.; Pereira, E.Q.; Azevedo, M.I.R. Edapho-climatic zoning for Eucalyptus urograndis in the state of Tocantins, Brazil. J. Bioenergy Food Sci. 2015, 2, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, T.P.; Prado, D.O.; Lyra, G.B.; Araújo, E.J.G.; Lyra, G.B. Edaphic-Climatic Zoning of Eucalyptus Species in the Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Floresta Ambient 2019, 26, e20160369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevanto, S.; Ryan, M.; Dickman, L.T.; Derome, D.; Patera, A.; Defraeye, T.; Pangle, R.E.; Hudson, P.J.; Pockman, W.T. Is desiccation tolerance and avoidance reflected in xylem and phloem anatomy of two coexisting arid-zone coniferous trees? Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1551–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencuccini, M.; Hölttä, T.; Sevanto, S.; Nikinmaa, E. Concurrent measurements of change in the bark and xylem diameters of trees reveal a phloem-generated turgor signal. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, E.S.; Lopez-Salmeron, V.; Belevich, I.; Poschet, G.; Jung, I.; Grunwald, K.; Sevilem, I.; Jokitalo, E.; Hell, R.; Helariutta, Y.; et al. Strigolactone- and karrikin-independent SMXL proteins are central regulators of phloem formation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevanto, S.; McDowell, N.G.; Dickman, L.T.; Pangle, R.; Pockman, W.T. How do trees die? A test of the hydraulic failure and carbon starvation hypotheses. Plant Cell 2014, 37, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilhó, T.; Pereira, H.; Richter, H.G. Within–tree variation in phloem cell dimensions and proportions in Eucalyptus globulus. IAWA J. 2000, 21, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liesche, J.; Crivellaro, A.; Doležal, J.; Altman, J.; Chiatante, D.; Dimitrova, A.; Fan, Z.; Fu, P.; Forest, F.; et al. Physical constraints and environmental factors shape phloem anatomical traits in woody angiosperm species. New Phytol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom, R.; Wright, C.F. Incomplete Penetrance and Variable Expressivity: From Clinical Studies to Population Cohorts. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 920390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgins, J.W.; Krekling, T.; Franceschi, V.R. Distribution of calcium oxalate crystals in the secondary phloem of conifers: A constitutive defense mechanism? New Phytol. 2003, 159, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tooulakou, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Bresta, P.; Dotsika, E.; Orkoula, M.G.; Kontoyannis, C.G.; Fasseas, C.; Liakopoulos, G.; Klapa, M.I.; et al. Reevaluation of the plant “gemstones”: Calcium oxalate crystals sustain photosynthesis under drought conditions. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1215793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furch, A.C.; Hafke, J.B.; Schulz, A.; van Bel, A.J. Ca2+-mediated remote control of reversible sieve tube occlusion in Vicia faba. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2827–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.A.; Beecher, S.D.; Clerx, L.; Gersony, J.T.; Knoblauch, J.; Losada, J.M.; Jensen, K.H.; Knoblauch, M.; Holbrook, N.M. Maintenance of carbohydrate transport in tall trees. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.F. Die-Back and Growth of Eucalypt Clones in Different Doses of Fertilizer. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2011; 56p. [Google Scholar]

- Gričar, J.; Prislan, P.; de Luis, M.; Gryc, V.; Hacurová, J.; Vavrčík, H.; Čufar, K. Plasticity in variation of xylem and phloem cell characteristics of Norway spruce under different local conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 1982, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, A.; Simon-Gáspár, B.; Soós, G. The Application of a Self-Organizing Model for the Estimation of Crop Water Stress Index (CWSI) in Soybean with Different Watering Levels. Water 2021, 13, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Neumann, K.; Friedel, S.; Kilian, B.; Chen, M.; Altmann, T.; Klukas, C. Dissecting the phenotypic components of crop plant growth and drought responses based on high-throughput image analysis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4636–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foelkel, C.E.B. (Ed.) Casca da Árvore do Eucalipto: Aspectos Morfológicos, Fisiológicos, Florestais, Ecológicos e Industriais, Visando a Produção de Celulose e Papel. In Eucalyptus Online Book Newsletter; TAPPI: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005; pp. 13–63. Available online: http://www.eucalyptus.com.br/capitulos/capitulo_casca.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Arets, E.J.M.M.; van der Meer, P.J.; Verwer, C.C.; Hengelveld, G.M.; Tolkamp, G.W.; Nabuurs, G.J.; van Oorschot, M. Global Wood Production: Assessment of Industrial Round Wood Supply from Forest Management Systems in Different Global Regions; Alterra-Rapport 1808; Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; 80p. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Borralho, N.M.G. Genetic gains and levels of relatedness from best linear unbiased prediction selection of Eucalyptus urophylla for pulp production in southeastern China. Can. J. For. Res. 2000, 30, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupin, S.; Zaruma, D.U.G.; de Souza, C.S.; Cambuim, J.; Coleto, A.L.; Alves, P.F.; Pavan, B.E.; de Moraes, M.L.T. Genetic parameters for growth traits, bark thickness and basic density of wood in progenies of Eucalyptus urophylla S.T. Blake. Sci. For. 2017, 45, 455–465. [Google Scholar]

- Paludeto, J.G.Z.; Bush, D.; Estopa, R.A.; Tambarussi, E.V. Genetic control of diameter and bark percentage in spotted gum (Corymbia spp.): Can we breed eucalypts with more wood and less bark? South. For. 2020, 82, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Essentials of the self-organizing map. Neural Netw. 2013, 37, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Bailey-Serres, J. Flood adaptive traits and processes: An overview. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, M.E.; Osteryoung, K.W.; Crafts-Brandner, S.J.; Vierling, E. Exceptional sensitivity of Rubisco activase to thermal denaturation in vitro and in vivo. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raturi, V.; Zinta, G. HSFA1 heat shock factors integrate warm temperature and heat signals in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1165–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, T.A.; Atkinson, W.; Fan, M.; Simkin, A.J.; Jindal, P.; Lawson, T. Impact of climate-driven changes in temperature on stomatal anatomy and physiology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2025, 380, 20240244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Cao, J.; Ge, K.; Li, L. The site of water stress governs the pattern of ABA synthesis and transport in peanut. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, M.J.; Coelho, D.; David, M.M. Response to seasonal drought in three cultivars of Ceratonia siliqua: Leaf growth and water relation. Tree Physiol. 2001, 21, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clone—Samples | Phenotype | Pedigree |

|---|---|---|

| E1-1, E1-2, E1-3 | tolerant | E. urophylla |

| E2-4, E2-5, E2-6 | tolerant | E. urophylla |

| E3-7, E3-8, E3-9 | tolerant | E. grandis × E. urophylla |

| E4-10, E4-11, E4-12 | semi-tolerant | E. grandis |

| E5-13, E5-14, E5-15 | semi-tolerant | E. grandis × E. urophylla |

| E6-16, E6-17, E6-18 | semi-tolerant | E. grandis × E. urophylla |

| E7-19, E7-20, E7-21 | mod-susceptible | E. grandis |

| E8-22, E8-23, E8-24 | susceptible | E. urophylla |

| E9-25, E9-26, E9-27 | susceptible | E. grandis |

| EPD Score | Symptoms | Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Level 0 | asymptomatic plants | E1-1, E1-2, E1-3, E2-4, E2-5, E2-6, E3-7, E4-10, E4-11, E5-13, E5-14, E5-15, E6-16, E6-17, E6-18, E7-21 |

| Level 1 | depressed surface lesion, cracking and slight detachment of the bark (“scaling”), randomly distributed on the trunk or branches | E3-8, E3-9, E4-12, E7-19, E7-20, E8-23, E8-24 |

| Level 2 | drying of the basal third leaves of the crown, cracking of the bark and swelling at specific points on the stem or randomly distributed along the main stem or branches | E8-22 |

| Level 3 | dieback, bifurcation of the main trunk, sprouting, formation of corky bark, release of bark (exophylactic periderm) and edema (callosity or rough appearance) on the leaves | E9-25, E9-26, E9-27 |

| Level 4 | drying canopy and plant death | - * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Picoli, E.A.d.T.; da Costa, W.G.; Ladeira, J.d.S.; Jacomini, F.A.; Almeida, M.N.F.; Kleine, A.A.; Vidaurre, G.B.; Moulin, J.C.; Balmant, K.M.; Cecon, P.R.; et al. Beyond the Wood Log: Relationships Among Bark Anatomy, Stem Diameter, and Tolerance to Eucalypt Physiological Disorder (EPD) in Cultivated Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex Maiden and E. urophylla T. Blake. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040124

Picoli EAdT, da Costa WG, Ladeira JdS, Jacomini FA, Almeida MNF, Kleine AA, Vidaurre GB, Moulin JC, Balmant KM, Cecon PR, et al. Beyond the Wood Log: Relationships Among Bark Anatomy, Stem Diameter, and Tolerance to Eucalypt Physiological Disorder (EPD) in Cultivated Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex Maiden and E. urophylla T. Blake. International Journal of Plant Biology. 2025; 16(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040124

Chicago/Turabian StylePicoli, Edgard Augusto de Toledo, Weverton Gomes da Costa, Josimar dos Santos Ladeira, Franciely Alves Jacomini, Maria Naruna Felix Almeida, Alaina Anne Kleine, Graziela Baptista Vidaurre, Jordão Cabral Moulin, Kelly M. Balmant, Paulo Roberto Cecon, and et al. 2025. "Beyond the Wood Log: Relationships Among Bark Anatomy, Stem Diameter, and Tolerance to Eucalypt Physiological Disorder (EPD) in Cultivated Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex Maiden and E. urophylla T. Blake" International Journal of Plant Biology 16, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040124

APA StylePicoli, E. A. d. T., da Costa, W. G., Ladeira, J. d. S., Jacomini, F. A., Almeida, M. N. F., Kleine, A. A., Vidaurre, G. B., Moulin, J. C., Balmant, K. M., Cecon, P. R., Zauza, E. Â. V., & Guimarães, L. M. d. S. (2025). Beyond the Wood Log: Relationships Among Bark Anatomy, Stem Diameter, and Tolerance to Eucalypt Physiological Disorder (EPD) in Cultivated Clones of Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex Maiden and E. urophylla T. Blake. International Journal of Plant Biology, 16(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040124