Unlocking the Potential of Biostimulants: A Review of Classification, Mode of Action, Formulations, Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Sustainable Intensification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classification and Composition of Biostimulants

2.1. A Framework for Categorization

2.2. Functional Classification and Regulatory Overlap

2.3. Formulation Technologies: (Active in Nature Versus Inactive)

2.4. Modes of Action: The Way Biostimulants Work

3. Efficacy Under Specific Abiotic Stresses

| Abiotic Stress | Key Physiological Challenge | Effective Biostimulant Types | Primary Mechanism of Mitigation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Osmotic stress, Oxidative damage | PGPR, Seaweed extracts, Humic acids | Osmolyte accumulation, Antioxidant induction, Improved root architecture | [42] |

| Salinity | Iron toxicity, Osmotic stress | Halotolerant PGPR, AMF, Amino acids | Ion homeostasis (K+/Na+), Osmotic adjustment, Antioxidant defense | [56] |

| Heat Stress | Protein denaturation, Membrane instability | Trichoderma spp., PGPR, Seaweed extracts | Heat-shock protein (HSP) induction, Membrane stabilization | [53] |

| Chilling Stress | Membrane rigidification, ROS generation | Microbial consortia, Seaweed extracts | Cryoprotectant synthesis, Antioxidant defense | [70] |

| Flooding | Hypoxia, Reduced nutrient uptake | Azospirillum, Pseudomonas spp. | Aerenchyma formation, Anaerobic metabolism support | [55] |

4. Efficacy Against Biotic and Physiological Stresses

4.1. Suppression of Pathogens and Nematodes

4.2. Alleviation of Physiological Stresses

5. Performance Variability and Influencing Factors

5.1. Fundamental Principles Governing Variability

5.2. Environmental and Edaphic Determinants

5.3. Climatic and Management Influences

6. The Greenhouse vs. Field Efficacy Disparity

Limitations of Controlled Environment Research

7. Crop-Specific Responses to Biostimulants

8. Biostimulants’ Interactions with Soil Amendments

| Amendment | Primary Effect on Soil | Interaction with Microbial Biostimulants | Interaction with Non-Microbial Biostimulants | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composted Manure | Adds organic matter & nutrients; improves soil structure. | Synergistic: Provides a stable habitat and complex carbon sources that enhance microbial activity and survival. | Additive/Synergistic: Improves soil conditions for root growth and nutrient retention, enhancing the biostimulant’s environment. | [123,124,126] |

| Fresh Manure | High in soluble N, P and K and can be unstable. | Antagonistic: May cause ammonia toxicity and introduce competitive native microbes that inhibit inoculated strains. Added nutrients reduce response by nutrient solubilizer microbes. | Variable: Potential for salt stress and rapid degradation of organic compounds; benefits uncertain. | [78,81,123,124] |

| Biochar | Increases CEC and porosity; enhances water retention. | Synergistic: Porous structure provides protective microhabitats, buffering microbes from environmental stress. | Antagonistic: High surface area can adsorb organic bioactive compounds, reducing their plant availability. | [85,124,126] |

| Wood Chips/Mulch | High C:N ratio; leads to nitrogen immobilization during decomposition. | Antagonistic: Nitrogen starvation limits the growth and metabolic activity of both plants and N-dependent microbes. | Antagonistic: Poor plant growth due to N deficiency can mask or negate any potential biostimulant effect. | [124,130] |

| Lime | Raises soil pH; can reduce aluminum toxicity. | Variable: Effect is pH dependent. May favor certain bacterial communities but can inhibit acid-tolerant fungi. | Variable: Alters the solubility, stability, and availability of organic compounds and nutrients. | [131,132] |

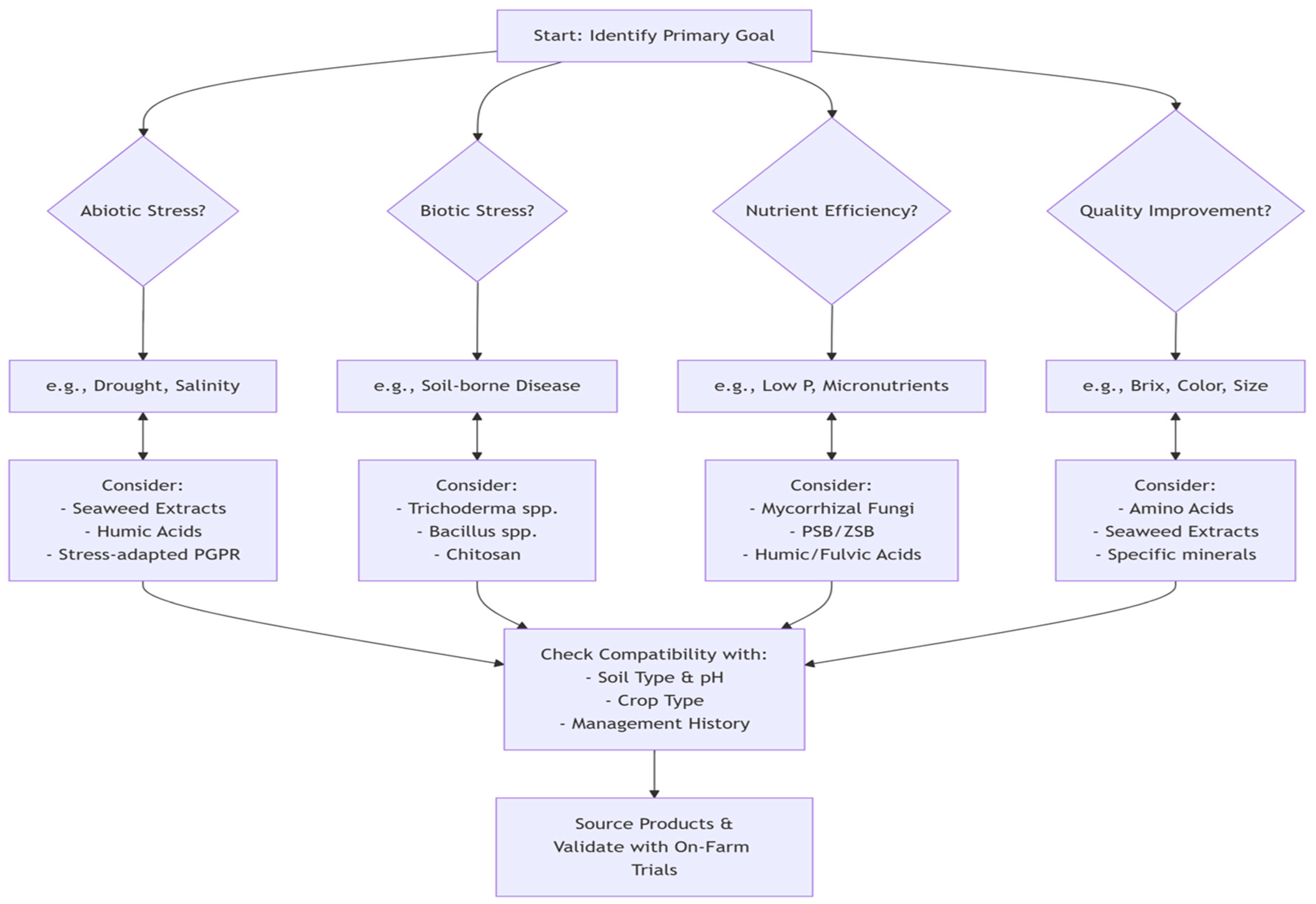

9. Observations and Recommendations

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate |

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| BNF | Biological Nitrogen Fixation |

| CEC | Cation Exchange Capacity |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| Fe | Iron |

| IPM | Integrated Pest Management |

| ISR | Induced Systemic Resistance |

| NGP | North Great Plains |

| NUE | Nutrient Use Efficiency |

| PGPR | Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| PGPM | Plant-Growth-Promoting Microorganisms |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SAR | Systemic Resistance |

| PGBF | Plant-growth-Promoting Fungi |

References

- United Nations. United Nations Population Prospects 2024. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Fritschi, F.B.; Mittler, R. Global warming, climate change, and environmental pollution: Recipe for a multifactorial stress combination disaster. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: Findings and issues. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reganold, J.P.; Wachter, J.M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2012, 485, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardin, P.D. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Doležal, K. Editorial: Growth regulators and biostimulants: Upcoming opportunities. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1209499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sible, C.; Below, F. Role of Biologicals in Enhancing Nutrient Efficiency in Corn and Soybean. Crop. Soils 2023, 56, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sible, C.N.; Seebauer, J.R.; Below, F.E. Biostimulant or biological? The complexity of defining, categorizing, and regulating microbial inoculants. Agric. Environ. Lett. 2025, 10, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Heick, T.M.; Kemmitt, G.M.; Bryson, R.; Brix, H. Instant Insights: Fungicide Resistance in Cereals; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, D.; Camberato, J.; Nafziger, E.; Kaiser, D.; Nelson, K.; Ruiz-Diaz, D.; Lentz, E.; Steinke, K.; Grove, J.; Ritchey, E.; et al. Performance of Selected Commercially Available Asymbiotic N-Fixing Products in the North Central Region; North Dakota State Extension: Fargo, ND, USA, 2023; Volume 4. Available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/performance-selected-commercially-available-asymbiotic-n-fixing-products (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Raymond, J.; Siefert, J.L.; Staples, C.R.; Blankenship, R.E. The natural history of nitrogen fixation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellriegel, H.; Wilfarth, H. Untersuchungen über die Stickstoffnahrung der Gramineen und Leguminosen; Hanbooks: Norderstedt, Germany, 1888; Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/27102 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Blunden, G. The effects of aqueous seaweed extract as a fertilizer additive. Proc. Int. Seaweed Symp. 1972, 7, 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Swarupa, P.; Kesari, K.K.; Kumar, A. Microbial inoculants as plant biostimulants: A review on risk status. Life 2022, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černohlávková, J.; Jarkovský, J.; Nešporová, M.; Hofman, J. Variability of soil microbial properties: Effects of sampling, handling and storage. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 2102–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, B.; Kamilova, F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, M.; Campana, E.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. An Appraisal of Nonmicrobial Biostimulants’ Impact on the Productivity and Mineral Content of Wild Rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.) Cultivated under Organic Conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L. Physiological responses to humic substances as plant growth promoters. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ugurlar, F. Non-microbial Biostimulants for Quality Improvement in Fruit and Leafy Vegetables. In Growth Regulation and Quality Improvement of Vegetable Crops: Physiological and Molecular Features; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 457–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, M.; Cotas, J.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L. Seaweed polysaccharides in agriculture: A next step towards sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Nardi, S.; Cardarelli, M.; Ertani, A.; Lucini, L.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Protein hydrolysates as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Freitas, H.; Dias, M.C. Strategies and prospects for biostimulants to alleviate abiotic stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1024243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datnoff, L.E.; Elmer, W.H.; Huber, D.M. (Eds.) Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease; APS Press—The American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2007; p. 278. ISBN 978-0-89054-346-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.G. A review of the applications of chitin and its derivatives in agriculture to modify plant-microbial interactions and improve crop yields. Agronomy 2013, 3, 757–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, A.; Bahabadi, S.E.; Beyzaei, H.; Mohammadi, Y.; Nusrat, E.; Sharifan, H. Nano-enhanced potassium biostimulants: Augmenting wheat yield, antioxidant activity, and micronutrient bioavailability in arid agricultural systems. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2025, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, D.P.K.; Sukla, L.B.; Bishoyi, A.K. Biosynthesis of Phosphorus Nanoparticles for Sustainable Agroecosystems: Next Generation Nanotechnology Application for Improved Plant Growth. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 14555–14565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ahmed, T.; Noman, M.; Qi, Y.; Ijaz, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Sun, L.; Qi, X.; Li, B.; et al. Immunomodulatory nano-biostimulants remodel transcriptome and metabolome for enhancing bayberry resilience against twig blight disease. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulogne, I.; Mirande-Ney, C.; Bernard, S.; Bardor, M.; Mollet, J.C.; Lerouge, P.; Driouich, A. Glycomolecules: From “sweet immunity” to “sweet biostimulation”? Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.Z.; Aranda, F.L.; Hernandez-Tenorio, F.; Garrido-Miranda, K.A.; Meléndrez, M.F.; Palacio, D.A. Polyelectrolytes for environmental, agricultural, and medical applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Adeleke, B.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Fayose, C.A.; Adeyemi, U.T.; Gbadegesin, L.A.; Omole, R.K.; Johnson, R.M.; Uthman, Q.O.; Babalola, O.O. Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: A case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apone, F.; Tito, A.; Carola, A.; Arciello, S.; Tortora, A.; Filippini, L.; Monoli, I.; Cucchiara, M.; Gibertoni, S.; Chrispeels, M.J.; et al. A mixture of peptides and sugars derived from plant cell walls increases plant defense responses to stress and attenuates ageing-associated molecular changes in cultured skin cells. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 145, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejela, T. Phytohormone-producing rhizobacteria and their role in plant growth. In New Insights into Phytohormones; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; Rodríguez-Morgado, B.; Gómez, I.; Franco-Andreu, L.; Benítez, C.; Parrado, J. Use of biofertilizers obtained from sewage sludges on maize yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 78, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.S.; Fleming, C.; Selby, C.; Rao, J.R.; Martin, T. Plant biostimulants: A review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Huang, Y.; Ge, W.; Jia, Z.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Involvement of jasmonic acid, ethylene and salicylic acid signaling pathways behind the systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma longibrachiatum H9 in cucumber. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Cortés-Penagos, C.; López-Bucio, J. Trichoderma virens, a plant beneficial fungus, enhances biomass production and promotes lateral root growth through an auxin-dependent mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1579–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Gui, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Guo, J.; Niu, D. Induced systemic resistance for improving plant immunity by beneficial microbes. Plants 2022, 11, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; Kolnaar, R.; Ravensberg, W.J. Mode of action of microbial biological control agents against plant diseases: Relevance beyond efficacy. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y.T.; He, J.; Gao, M.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18220–18225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Francioso, O.; Quaggiotti, S.; Nardi, S. Humic substances biological activity at the plant-soil interface: From environmental aspects to molecular factors. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Signal. Behav. 2006, 1, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dong, W.; Murray, J.; Wang, E. Innovation and appropriation in mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 1573–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Sambo, P.; Sanchez-Cortes, S.; Nardi, S. Capsicum chinensis L. growth and nutraceutical properties are enhanced by biostimulants in a long-term period: Chemical and metabolomic approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, H.M.; Fiaz, S.; Hafeez, S.; Zahra, S.; Shah, A.N.; Gul, B.; Aziz, O.; Rahman, M.U.; Fakhar, A.; Rafique, M.; et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria eliminate the effect of drought stress in plants: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 875774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashan, Y. Inoculants of plant growth-promoting bacteria for use in agriculture. Biotechnol. Adv. 1998, 16, 729–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Kant, C.; Turan, M. Humic acid application alleviate salinity stress of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants de-creasing membrane leakage. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 7, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, R.B.S.; Shahzad, R.; Tayade, R.; Shahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Ali, M.W.; Yun, B.-W. Evaluation potential of PGPR to protect tomato against Fusarium wilt and promote plant growth. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilangumaran, G.; Smith, D.L. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in amelioration of salinity stress: A systems biology perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Rodríguez, R.; Sáenz-Mata, J.; Trejo-Calzada, R.; Ochoa-García, P.P.; Arreola-Ávila, J.G. Halotolerant rhizobacteria promote plant growth and decrease salt stress in Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K.P.; Mahawar, L. Coping with salt stress-interaction of halotolerant bacteria in crop plants: A mini review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1077561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahed, K.R.; Saini, A.K.; Sherif, S.M. Coping with the cold: Unveiling cryoprotectants, molecular signaling pathways, and strategies for cold stress resilience. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1246093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E. Adaptation to changing osmolarity. In Bacillus Subtilis and Its Closest Relatives; Sonen-shein, A.L., Hoch, J.A., Losick, R., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, P.; Zha, Q.; Hui, X.; Tong, C.; Zhang, D. Research progress of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improving plant resistance to temperature stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Scopa, A.; Manfra, M.; De Nisco, M.; Tenore, G.; Troisi, J.; Di Fiori, R.; Novellino, E. Trichoderma harzianum strain T-22 induces changes in phytohormone levels in cherry rootstocks (Prunus cerasus × P. canescens). Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 65, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Moon, Y.-S.; Hamayun, M.; Khan, M.A.; Bibi, K.; Lee, I.-J. Pragmatic role of microbial plant biostimulants in abiotic stress relief in crop plants. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. The application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as microbial biostimulant, sustainable approaches in modern agriculture. Plants 2023, 12, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buga, N.; Petek, M. Use of Biostimulants to Alleviate Anoxic Stress in Waterlogged Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata)—A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Kim, W.-C. Plant growth promotion under water: Decrease of waterlogging-induced ACC and ethylene levels by ACC deaminase-producing bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yssel, J.; Everaerts, V.; Van Hemelrijk, W.; Bylemans, D.; Setati, M.E.; Lievens, B.; Blancquaert, E.; Crauwels, S. Assessing the potential of seaweed extracts to improve vegetative, physiological and berry quality parameters in Vitis vinifera cv. Chardonnay under cool climatic conditions. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The current status of its application in agriculture for the biocontrol of fungal phytopathogens and stimulation of plant growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Shao, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xun, W.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Biocontrol mechanisms of Bacillus: Improving the efficiency of green agriculture. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 2250–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.Y.; Kang, S. Trichoderma application methods differentially affect the tomato growth, rhizomicrobiome, and rhizosphere soil suppressiveness against Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1366690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonim, M. Induction of systemic resistance against Fusarium wilt in tomato by seed treatment with the biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, M.; Hafeez, F.Y. Characterization of siderophore producing bacterial strain Pseudomonas fluorescens Mst 8.2 as plant growth promoting and biocontrol agent in wheat. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 6308–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Rideout, S.; Langston, D. Cultural Management of Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans) in Greenhouse Tomatoes Production. Va. Coop. Ext. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijri, M. Microbial-based plant biostimulants. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.A.; Kainz, K.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Madeo, F. Microbial wars: Competition in ecological niches and within the microbiome. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maini, P. The experience of the first biostimulant, based on amino acids and peptides: A short retrospective review on the laboratory researches and the practical results. Fertil. Agrorum 2006, 1, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.; Cotas, J.; Gonçalves, A.M. Seaweed Proteins: A Step towards Sustainability? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.-C.; Xing, Y.-X.; Ma, Y.-H.; Li, S.-H.; Jia, Y.-X.; Yang, H.-C.; Zhang, F.-H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance soybean phosphorus uptake and soil fertility under saline-alkaline stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Huang, D. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant abiotic stress. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1323881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyno, G.; Danesh, Y.R.; Çevik, R.; Teniz, N.; Demir, S.; Durak, E.D.; Farda, B.; Mignini, A.; Djebaili, R.; Pellegrini, M.; et al. Synergistic benefits of AMF: Development of sustainable plant defense system. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1551956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nleya, T.; Clay, S.A.; Arinaitwe, U. Poor Emergence of Brassica Species in Saline–Sodic Soil Is Improved by Biochar Addition. Agronomy 2025, 15, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Nleya, T.M.; Kafle, R.; Clay, S.A. Can Beneficial Microbial, and Biochar Amendments Health and Remediate Plant Salt Stress in Saline Soils? In Proceedings of the ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 9–12 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: Advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms and microbial community effects. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Kumar, V.; Kohli, S.K.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Bhardwaj, R.; Zheng, B. Phytohormones regulate accumulation of osmolytes under abiotic stress. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Scartazza, A.; Gresta, F.; Loreti, E.; Biasone, A.; Di Tommaso, D.; Piaggesi, A.; Perata, P. Ascophyllum nodosum seaweed extract alleviates drought stress in Arabidopsis by affecting photosynthetic performance and related gene expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atasoy, M.; Ordóñez, A.Á.; Cenian, A.; Djukić-Vuković, A.; A Lund, P.; Ozogul, F.; Trček, J.; Ziv, C.; De Biase, D. Exploitation of microbial activities at low pH to enhance planetary health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 48, fuad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y. Interactive effects of soil pH and substrate quality on microbial utilization. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2020, 96, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.G.; Majrashi, M.A.; Ibrahim, H.M. Improving the physical properties and water retention of sandy soils by the synergistic utilization of natural clay deposits and wheat straw. Sustainability 2023, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Frame, W.H.; Reiter, M.; Langston, D.; Tech, W.E.T.V. Refining N Rates and NUE with Commercial BNF in the US Cotton Belt. Virginia Cooperative Extension. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385722649 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial–fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaramaiah, R.H.; Martins, C.S.; Egidi, E.; Macdonald, C.A.; Wang, J.-T.; Liu, H.; Reich, P.B.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Singh, B.K. Soil function-microbial diversity relationship is impacted by plant functional groups under climate change. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 200, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannipieri, P.; Hannula, S.E.; Pietramellara, G.; Schloter, M.; Sizmur, T.; Pathan, S.I. Legacy effects of rhizodeposits on soil microbiomes: A perspective. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadzie, F.A.; Moles, A.T.; Erickson, T.E.; de Lima, N.M.; Muñoz-Rojas, M. Inoculating native microorganisms improved soil function and altered the microbial composition of a degraded soil. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32, e14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Perdomo, F.; Camelo-Rusinque, M.; Criollo-Campos, P.; Bonilla-Buitrago, R. Effect of temperature and pH on the biomass production of Azospirillum brasilense C16 isolated from Guinea grass. Pastos Y Forraje 2015, 38, 231–233. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A.L. Diffusion the crucial process in many aspects of the biology of bacteria. In Advances in Microbial Ecology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Or, D. Aquatic habitats and diffusion constraints affecting microbial coexistence in unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Clay, S.A.; Nleya, T. Growth, yield, and yield stability of canola in the Northern Great Plains of the United States. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-Jones, K.; Robinson, S.L.; Veen, G.F.; Manzoni, S.; van der Putten, W.H. Microbial storage and its implications for soil ecology. ISME J. 2022, 16, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, H.M.; Chen, Y.X. Effects of 2,4-dichlorophenol, pentachlorophenol and vegetation on microbial characteristics in a heavy metal polluted soil. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part B 2007, 42, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessitsch, A.; Gyamfi, S.; Tscherko, D.; Gerzabek, M.H.; Kandeler, E. Activity of microorganisms in the rhizosphere of herbicide treated and untreated transgenic glufosinate-tolerant and wildtype oilseed rape grown in containment. Plant Soil 2005, 266, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P. The control of microbiological problems. Pulp Pap. Ind. 2015, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbeva, P.; van Elsas, J.D.; van Veen, J.A. Rhizosphere microbial community and its response to plant species and soil history. Plant Soil 2008, 302, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Yabwalo, D.N.; Hangamaisho, A. Advances in Micronutrients Signaling, Transport, and Integration for Optimizing Cotton Yield. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, L.E.; Grenzer, J.; Heinze, J.; Schittko, C.; Kulmatiski, A. Greenhouse- and Field-Measured Plant-Soil Feedbacks Are Not Correlated. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agho, C.; Avni, A.; Bacu, A.; Balazadeh, S.; Baloch, F.S.; Bazakos, C.; Čereković, N.; Chaturvedi, P.; Chauhan, H.; De Smet, I.; et al. Integrative approaches to enhance reproductive resilience of crops for climate-proof agriculture. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100704. [Google Scholar]

- Camli-Saunders, D.; Villouta, C. Root exudates in controlled environment agriculture: Composition, function, and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1567707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y. The function of root exudates in the root colonization by beneficial soil rhizobacteria. Biology 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshelion, M.; Dietz, K.-J.; Dodd, I.C.; Muller, B.; E Lunn, J. Guidelines for designing and interpreting drought experiments in controlled conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 4671–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, A.R.; Nunamaker, J.F.; Vogel, D.R. A comparison of laboratory and field research in the study of electronic meeting systems. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1990, 7, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A. Comparison between field research and controlled laboratory research. Arch. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2017, 1, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisi, R.M.; Bentley, G.E. Lab and field experiments: Are they the same animal? Horm. Behav. 2009, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mola, I.; Ottaiano, L.; Cozzolino, E.; Senatore, M.; Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Sacco, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Mori, M. Plant-based biostimulants influence the agronomical, physiological, and qualitative responses of baby rocket leaves under diverse nitrogen conditions. Plants 2019, 8, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Nain, P.; Kumar, A.; Joshi, S.; Punetha, H.; Sharma, P.K.; Siddiqui, S.; Alshaharni, M.O.; Algopishi, U.B.; Mittal, A. Next generation plant biostimulants & genome sequencing strategies for sustainable agriculture development. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1439561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, U.; Thomason, W.; Frame, W.H.; Reiter, M.S.; Langston, D. Optimizing Maize Agronomic Performance Through Adaptive Management Systems in the Mid-Atlantic United States. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Montaño, F.; Alias-Villegas, C.; Bellogín, R.A.; del Cerro, P.; Espuny, M.R.; Jiménez-Guerrero, I.; López-Baena, F.J.; Ollero, F.; Cubo, T. Plant growth promotion in cereal and leguminous agricultural important plants: From microorganism capacities to crop production. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, R.; Adak, A.; Verma, S.; Bidyarani, N.; Babu, S.; Pal, M.; Shivay, Y.S.; Nain, L. Cyanobacterial inoculation in rice grown under flooded and SRI modes of cultivation elicits differential effects on plant growth and nutrient dynamics. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Saadaoui, I.; Bibi, A.; Al-Ghouti, M.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. Applications, advancements, and challenges of cyanobacteria-based biofertilizers for sustainable agro and ecosystems in arid climates. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 25, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliki, S.; Al-Zabee, M.; Muter, D.M.; Jabbar, M.K.; Al-Mammori, H.Z.; Sallal, M. Mycorrhizal fungi and foliar fe fertilization improved soil microbial indicators and eggplant yield in the arid land soils. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2020, 21, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Ren, B.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M. Chemical and biological response of four soil types to lime application: An incubation study. Agronomy 2023, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, D.; Ventorino, V.; Fagnano, M.; Woo, S.L.; Pepe, O.; Adamo, P.; Caporale, A.G.; Carrino, L.; Fiorentino, N. Compost and microbial biostimulant applications improve plant growth and soil biological fertility of a grass-based phytostabilization system. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Herrero, R.; Vega-Jara, L.; García-Delgado, C.; Mayans, B.; Camacho-Arévalo, R.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Plaza, C.; Eymar, E. Synergistic effects of biochar and biostimulants on nutrient and toxic element uptake by pepper in contaminated soils. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilias, F.; Tsolis, V.; Zafeiriou, I.; Koukounaras, A.; Kalderis, D.; Chlouveraki, E.; Gasparatos, D. Effects of sewage sludge biochar and a seaweed extract-based biostimulant on soil properties, nutritional status and antioxidant capacity of lettuce plants in a saline soil with the risk of alkalinization. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 7271–7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, E.A.M.; Awad, E.-S.A.; Mohamed, I.R.; El-Hameed, A.M.A.; Feng, D.; Desoky, E.-S.M.; Algopishi, U.B.; Al Masoudi, L.M.; Elrys, A.S.; Mathew, B.T.; et al. Co-application of organic amendments and natural biostimulants on plants enhances wheat production and defense system under salt-alkali stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readyhough, T.; Neher, D.A.; Andrews, T. Organic Amendments alter soil hydrology and belowground microbiome of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, U.; Semple, K.T. Impact of biochar on organic contaminants in soil: A tool for mitigating risk? Agronomy 2013, 3, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossolani, J.W.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Merloti, L.F.; Moretti, L.G.; Costa, N.R.; Tsai, S.M.; Kuramae, E.E. Long-term lime and gypsum amendment increase nitrogen fixation and decrease nitrification and denitrification gene abundances in the rhizosphere and soil in a tropical no-till intercropping system. Geoderma 2020, 375, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Cui, W.; Qi, Z.; Zhou, W. Nitrogen Immobilization by Wood Fiber Substrates Strongly Affects the Photosynthetic Performance of Lettuce. Plants 2025, 14, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Carrión, V.J.; Yin, S.; Yue, Z.; Liao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, X. Acidic amelioration of soil amendments improves soil health by impacting rhizosphere microbial assemblies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 167, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Bååth, E. Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Primary Sources | Typical Mode of Action (MOA) | Example Products & Formulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Biostimulants | |||

| PGPR | Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Azospirillum, Rhizobium | Nutrient solubilization, N-fixation, phytohormone production, Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) | Utrisha™ N (liquid), TerraMax (granular) |

| Beneficial Fungi | Mycorrhizae (AMF), Trichoderma | Enhanced root surface area, nutrient/water uptake, pathogen antagonism | Trianum™ (powder), MycoApply® (granules, powder) |

| Non-Microbial Biostimulants | |||

| Humic Substances | Leonardite, peat, compost | Improve soil CEC & structure, nutrient uptake, hormone-like activity | Humifirst (liquid), (granular) |

| Seaweed Extracts | Brown algae: Ascophyllum nodosum | Betaines, polysaccharides, and phytohormones enhance stress tolerance | Acadian (liquid), Kelpak® (liquid) |

| Protein Hydrolysates | Animal/plant by-products | Source of bioavailable N, chelating agents, stress metabolite precursors | Terra-Sorb® (liquid) |

| Inorganic Compounds | Mineral deposits | Structural integrity (Si), induced resistance (Phosphites) | Sil-Matrix® (liquid), Nutri-Phite® (liquid) |

| Biostimulant Category | Primary Modes of Action (MOA) | Key Bioactive Compounds/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| PGPR (e.g., Bacillus, Pseudomonas) | N-fixation, P-solubilization, Phytohormone production (IAA), ISR, Antibiosis | IAA, Siderophores, ACC deaminase, Antibiotics, Exopolysaccharides |

| Beneficial Fungi (AMF, Trichoderma) | Enhanced nutrient/water uptake, Pathogen antagonism, ISR | Extensive hyphal network, Mycoparasitism, Chitinase enzymes |

| Seaweed Extracts | Osmotic adjustment, Antioxidant defense, Phytohormone-like activity | Betaines, Polysaccharides (alginates, laminarin), Cytokinins, Auxins |

| Humic Substances | Improved soil CEC, Root membrane permeability, Nutrient chelation | Humic acids, Fulvic acids, Polyphenols |

| Protein Hydrolysates/Amino Acids | Chelation, Osmoregulation, Metabolic precursors | Free L-amino acids, Peptides, Organic Nitrogen |

| Chitosan | Elicitation of plant defenses (SAR), Antimicrobial activity | Chitin derivatives, Oligosaccharides |

| Stress Category | Specific Challenge | Effective Biostimulant Types | Primary Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biotic Stress | Soil-borne pathogens (e.g., Fusarium, Pythium) | Trichoderma spp., PGPR (Bacillus, Pseudomonas) | Mycoparasitism, Competition, Antibiosis, Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) | [64,78] |

| Insect pests (e.g., aphids, mites) | Chitosan, Phenolic-rich plant extracts | Cell wall signification, Induction of defensive secondary metabolites | [74,75] | |

| Physiological Stress | Nutrient deficiency (e.g., P, Fe, Zn) | AMF, Humic substances, PSB | Nutrient solubilization, Chelation, Enhanced root surface area | [82,83] |

| Transplant shock | Amino acids, Seaweed extracts | Supply of organic N, Stimulation of root regeneration | [79] | |

| Poor fruit set/flowering | Amino acids, Microbial consortia | Improved pollen viability, Hormonal modulation | [53] | |

| Physical injury (hail, wind) | Amino acids, Seaweed extracts | Callus formation, Energy metabolism recovery | [8] |

| Crop Type | Key Challenges | Recommended Types | Application Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | Early establishment, nutrient efficiency | PGPR, Humic acids | Seed treatment, in-furrow |

| Legumes | Biological nitrogen fixation | Specific rhizobia | Seed inoculation |

| Vegetables | Soil diseases, transplant shock, quality | Trichoderma, AMF, Seaweed extracts | Soil incorporation, foliar |

| Plantations | Long-term soil health, periodic stress | Humic substances, AMF, Seaweed extracts | Broadcast granules, foliar |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arinaitwe, U.; Yabwalo, D.N.; Hangamaisho, A. Unlocking the Potential of Biostimulants: A Review of Classification, Mode of Action, Formulations, Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Sustainable Intensification. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040122

Arinaitwe U, Yabwalo DN, Hangamaisho A. Unlocking the Potential of Biostimulants: A Review of Classification, Mode of Action, Formulations, Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Sustainable Intensification. International Journal of Plant Biology. 2025; 16(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040122

Chicago/Turabian StyleArinaitwe, Unius, Dalitso Noble Yabwalo, and Abraham Hangamaisho. 2025. "Unlocking the Potential of Biostimulants: A Review of Classification, Mode of Action, Formulations, Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Sustainable Intensification" International Journal of Plant Biology 16, no. 4: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040122

APA StyleArinaitwe, U., Yabwalo, D. N., & Hangamaisho, A. (2025). Unlocking the Potential of Biostimulants: A Review of Classification, Mode of Action, Formulations, Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Sustainable Intensification. International Journal of Plant Biology, 16(4), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040122