Effects of a Media Prevention Program on Media-Related Knowledge and Awareness in Children and Their Parents: A Non-Randomized Controlled Cluster Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

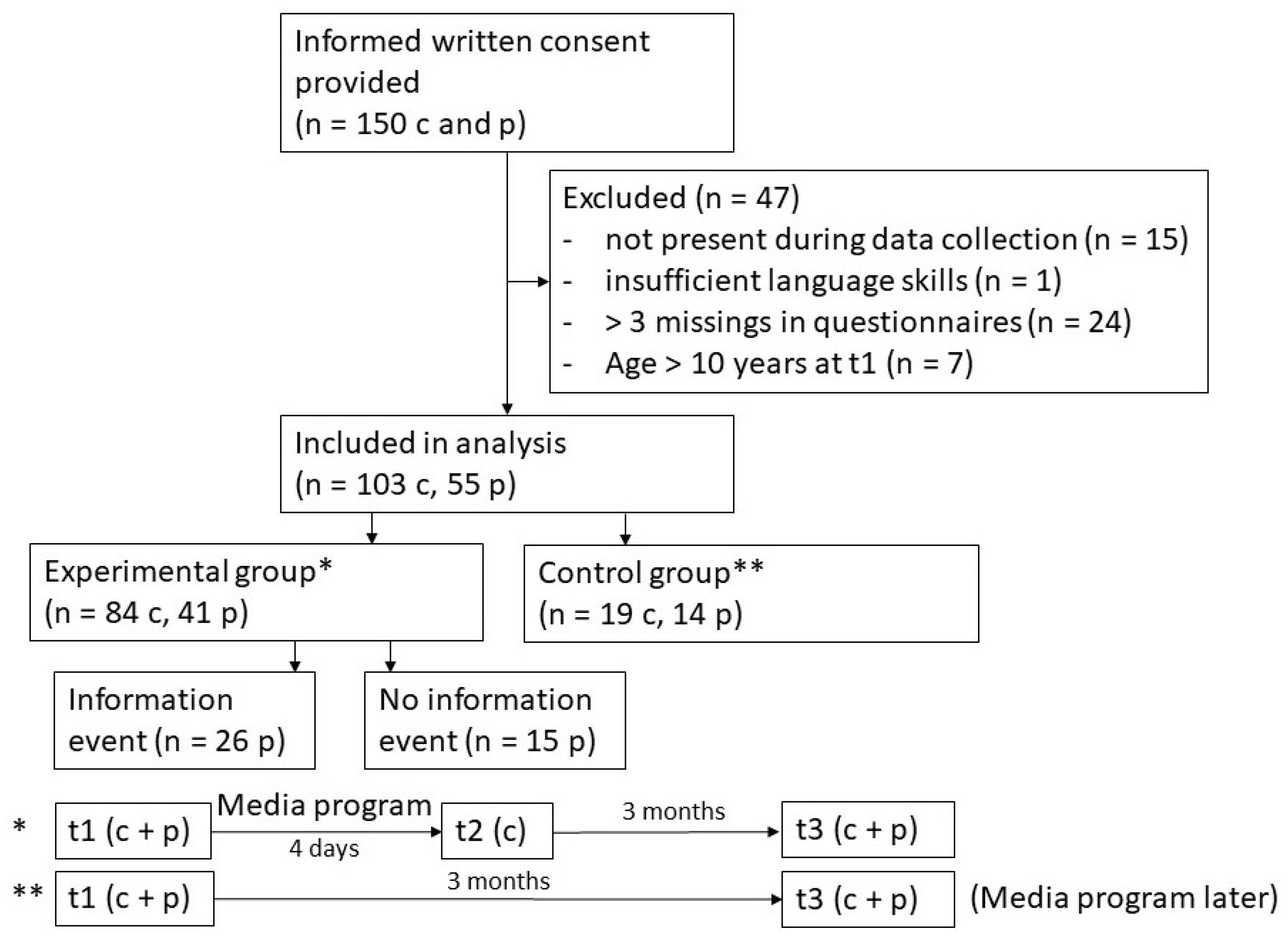

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Media Program

2.3. Evaluation Questionnaires

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description

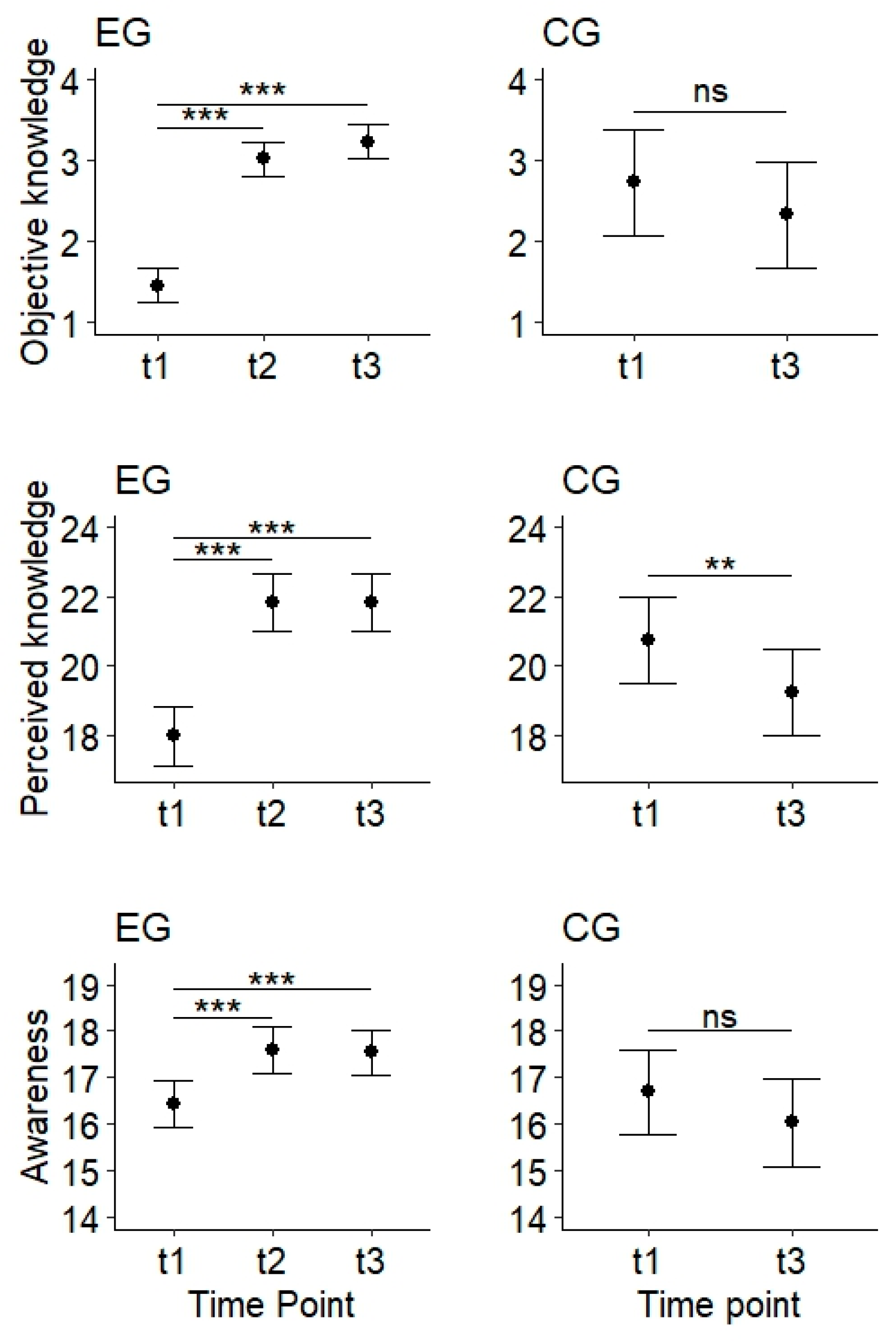

3.2. Effects of the Media Prevention Program in Children

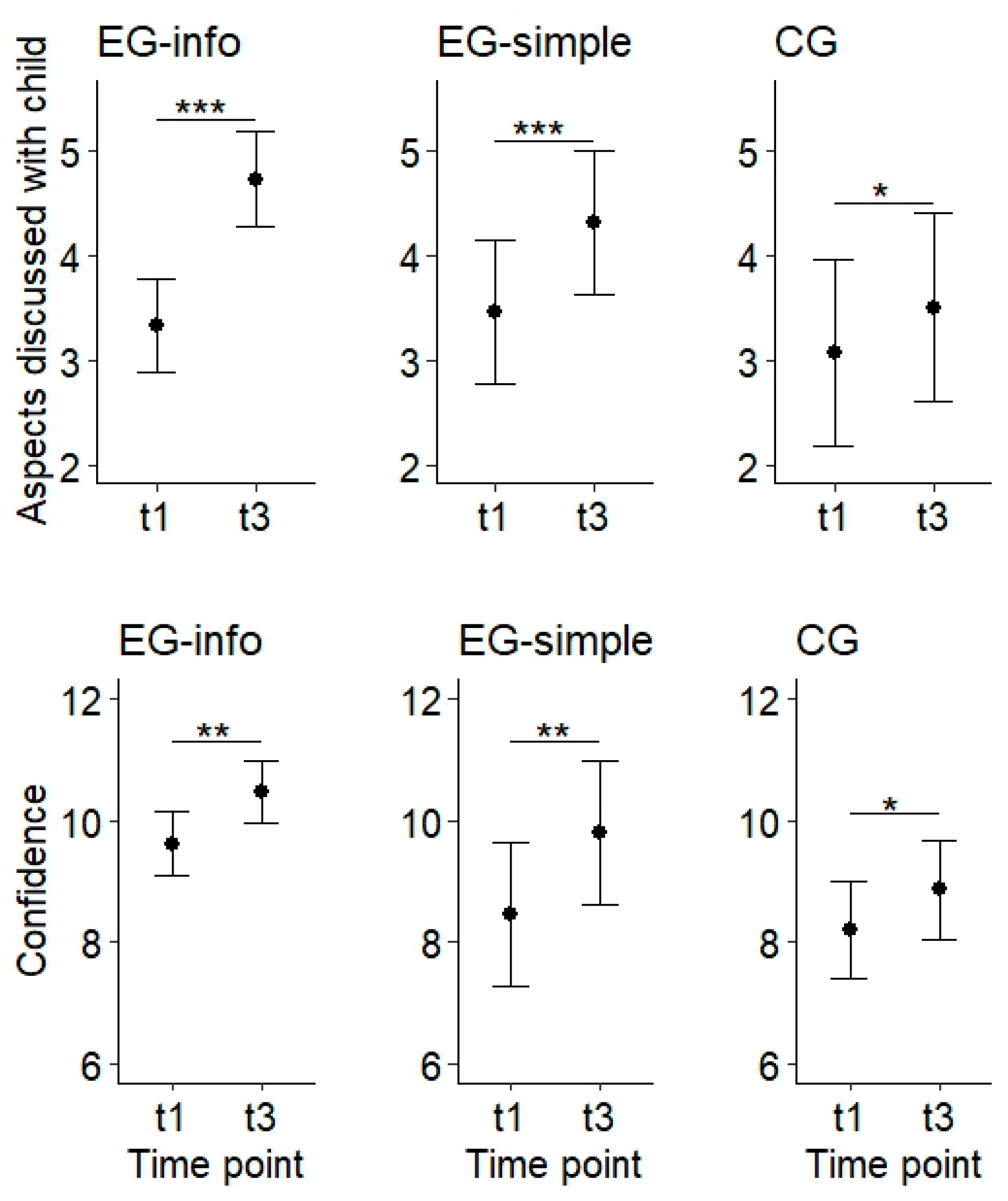

3.3. Effects of the Media Program in Parents

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the Media Prevention Program in Children

4.2. Effects of the Media Prevention Program in Parents

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EG | experimental group |

| CG | control group |

References

- Rideout, V.; Peebles, A.; Mann, S.; Robb, M.B. Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens; Common Sense: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rathgeb, T.; Schmid, T. KIM-Studie 2024: Basisuntersuchung Zum Medienumgang 6- Bis 13-Jähriger; Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest: Stuttgart, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Meier, A.; Beyens, I. Social Media Use and Its Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, F.W.; Ohmann, S.; von Gontard, A.; Popow, C. Internet Gaming Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Vogel, M.; Ludwig, J.; Grafe, N.; Körner, A.; Kiess, W. Reciprocal Longitudinal Associations Between Adolescents’ Media Consumption and Psychological Health. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Sasayama, D.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, T.; Kuraishi, Y.; Washizuka, S. Association between Children’s Difficulties, Parent-Child Sleep, Parental Control, and Children’s Screen Time: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel-Saldierna, M.; Méndez-Garavito, I.R.; Elizondo-Hernandez, E.; Fuentes-Orozco, C.; González-Ojeda, A.; Ramírez-Ochoa, S.; Cervantes-Pérez, E.; Vicente-Hernández, B.; Vázquez-Sánchez, S.J.; Chejfec-Ciociano, J.M.; et al. Social Media Use and Fear of Missing out: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in Junior High Students from Western Mexico. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, L.; Sølvhøj, I.N.; Danielsen, D.; Andersen, S. Electronic Media Use and Sleep in Children and Adolescents in Western Countries: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peracchia, S.; Curcio, G. Exposure to Video Games: Effects on Sleep and on Post-Sleep Cognitive Abilities. A Systematic Review of Experimental Evidences. Sleep Sci. 2023, 11, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Vogel, M.; Buzek, T.; Genuneit, J.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W. Reciprocal Longitudinal Associations between Adolescents’ Media Consumption and Sleep. Behav. Sleep Med. 2018, 7, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelantado-Renau, M.; Moliner-Urdiales, D.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Beltran-Valls, M.R.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Association Between Screen Media Use and Academic Performance Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Peschel, T.; Vogel, M.; Jurkutat, A.; Kiess, W. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations of Screen Time and Physical Activity with School Performance at Different Types of Secondary School. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, P.; Favez, N.; Liddle, H.; Rigter, H. Linking Parental Mediation Practices to Adolescents’ Problematic Online Screen Use: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Zhu, X. Parental Mediation and Adolescents’ Internet Use: The Moderating Role of Parenting Style. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Haddon, L.; Görzig, A.; Ólafsson, K. Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children: Full Findings and Policy Implications from the EU Kids Online Survey of 9–16 Year Olds and Their Parents in 25 Countries; EU Kids Online: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, T.; Meigen, C.; Kiess, W.; Vogel, M. Media Regulation Strategies in Parents of 4- to 16-Year-Old Children and Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szapary, A.; Feher, G.; Radvanyi, I.; Fejes, E.; Nagy, G.D.; Jancsak, C.; Horvath, L.; Banko, Z.; Berke, G.; Kapus, K. Problematic Usage of the Internet among Hungarian Elementary School Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-H.; Cheng, H.-Y. Problematic Internet Use among Elementary School Students: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 24, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S.E.; Borgen, A.L.; Radesky, J.S. Interactional Theory of Childhood Problematic Media Use. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lepeleere, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Stappen, V.; Huys, N.; Latomme, J.; Androutsos, O.; Manios, Y.; Cardon, G.; Verloigne, M. Parenting Practices as a Mediator in the Association Between Family Socio-Economic Status and Screen-Time in Primary Schoolchildren: A Feel4Diabetes Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Adair, P.; Coffey, M.; Harris, R.; Burnside, G. Identifying the Participant Characteristics That Predict Recruitment and Retention of Participants to Randomised Controlled Trials Involving Children: A Systematic Review. Trials 2016, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, K.; Te’eni-Harari, T. Systematic Review: Characteristics and Outcomes of in-School Digital Media Literacy Interventions, 2010–2021. J. Child. Media 2024, 18, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saletti, S.M.R.; Van den Broucke, S.; Chau, C. The Effectiveness of Prevention Programs for Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents and Youths: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2021, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Rennoldson, M.; Kuss, D.J. School-Based Prevention for Adolescent Internet Addiction: Prevention Is the Key. A Systematic Literature Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.; Hanewinkel, R.; Morgenstern, M. Effects of a Brief School-Based Media Literacy Intervention on Digital Media Use in Adolescents: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, K.; Halasy, K.; Schoenmaekers, S. A Randomized Efficacy Trial of a Cognitive-Behavioral Group Intervention to Prevent Internet Use Disorder Onset in Adolescents: The PROTECT Study Protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2017, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeun, Y.R.; Han, S.J. Effects of Psychosocial Interventions for School-Aged Children’s Internet Addiction, Self-Control and Self-Esteem: Meta-Analysis. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2016, 22, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Available online: https://www.R-Project.Org/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Matthes, J.; Thomas, M.F.; Stevic, A.; Schmuck, D. Fighting over Smartphones? Parents’ Excessive Smartphone Use, Lack of Control over Children’s Use, and Conflict. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 116, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Gama, A.; Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Nogueira, H.; Rosado-Marques, V.; Silva, M.-R.G.; Padez, C. Home vs. Bedroom Media Devices: Socioeconomic Disparities and Association with Childhood Screen- and Sleep-Time. Sleep Med. 2021, 83, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corkin, D.M.; Horn, C.; Pattison, D. The Effects of an Active Learning Intervention in Biology on College Students’ Classroom Motivational Climate Perceptions, Motivation, and Achievement. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 37, 1106–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Young, M.D.; Lloyd, A.B.; Wang, M.L.; Eather, N.; Miller, A.; Murtagh, E.M.; Barnes, A.T.; Pagoto, S.L. Involvement of Fathers in Pediatric Obesity Treatment and Prevention Trials: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Topic | Content | Variable(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| t1, t3 | Device ownership | Ownership of 5 devices (TV, smartphone, smartwatch, laptop/tablet, game console) Response options: yes; no | Number of own devices (range 0–5) |

| t1, t3 | Media use frequency | Usage frequency for 3 media activities (movies/series, video games, social media) Response options: (nearly) each day, ≥2 h (4); (nearly) each day, <2 h (3); 3–4 times/week (2); 1–2 times/week (1); less frequently or never (0) | Dichotomous: daily versus not daily, for each media activity; sum score (range 0–12, higher scores indicate more frequent use) |

| t1, t3 | Rules | Rules at home (movies/series, video games, social media) Response options: yes; no | Dichotomous: yes versus no, for each media activity |

| t3 | Media use contract | Media use contract Response options: yes; no | Dichotomous: yes versus no |

| t1, t2, t3 | Objective knowledge | 4 questions on media knowledge: 1. naming two components of secure passwords (open), 2. naming three behaviors that help in case of harassment on the Internet (open), 3. naming a search engine for children on the Internet (open), 4. naming who is responsible for photos on the Internet (response options: person on the photo (=correct); person taking the photo; person sending the photo) | Number of correct responses (range 0–4) |

| t1, t2, t3 | Perceived knowledge | Knowledge on 6 aspects of media use/Internet (age restrictions, online privacy, password security, online bullying, online search strategies, social media) Response options: not at all (1); rather no (2); rather yes (3); yes (4) | Sum score (range 6–24, higher scores indicate higher self-rated knowledge) a |

| t1, t2, t3 | Awareness | Awareness regarding 5 aspects of media use/Internet (photos on the Internet, trustworthiness of the Internet, online contact to strangers, cluelessness on the Internet, sharing personal data) Response options: not at all (1); rather no (2); rather yes (3); yes (4) | Sum score (range 5–20, higher scores indicate higher awareness) b |

| t1, t2 EG only | Group work | Pleasantness of group work Response options: very pleasant; rather pleasant; rather not pleasant; not pleasant at all | Dichotomous: very pleasant versus lower |

| t1, t2 EG only | Class climate | Satisfaction with the class mates Response options: very low; rather low; rather good; very good | Dichotomous: very good versus lower |

| Time | Topic | Content | Variable(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | Education | Highest school degree Response options: no school degree; lowest secondary school; middle secondary school; highest secondary school | Dichotomous: high versus low/middle (“no school degree” was not reported) |

| t1 | Media use frequency | Usage time for 3 media activities (movies/series, video games, social media) Response options: (nearly) each day, ≥3 h (4); (nearly) each day, <3 h (3); 3–4 times/week (2); 1–2 times/week (1); less frequently or never (0) | Dichotomous: daily versus not daily, for each media activity; sum score (range 0–12, higher scores indicate more frequent use) |

| t1, t2 | Discussion with child | Discussion on 5 topics (age restriction, online bullying, online shopping, fake news, online privacy) Response options: yes; no | Number of topics already discussed (range 0–5) |

| t1, t2 | Confidence | Confidence regarding 3 subjects (media education, finding information regarding media education, applications for secure use) Response options: not at all (1); rather not (2); rather yes (3); totally (4) | Sum score (range 3–12, higher scores indicate more confidence) a |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG (n = 84) | CG (n = 19) | EG (n = 84) | EG (n = 84) | CG (n = 19) | ||

| Age | n (%) 9 years | 30 (36%) | 8 (42%) | - | 14 (17%) | 6 (32%) |

| n (%) 10 years | 54 (64%) | 11 (58%) | - | 70 (83%) | 13 (68%) | |

| Sex | n (%) male | 37 (44%) | 6 (32%) | - | - | - |

| n (%) female | 47 (56%) | 13 (68%) | - | - | - | |

| Device ownership | ||||||

| TV a | n (%) | 18 (21%) | 6 (32%) | - | 16 (19%) | 6 (32%) |

| Smartphone a | n (%) | 49 (59%) | 12 (63%) | - | 60 (71%) | 14 (74%) |

| Smartwatch a | n (%) | 21 (25%) | 4 (21%) | - | 24 (25%) | 4 (21%) |

| Laptop/Tablet a | n (%) | 51 (61%) | 5 (28%) | - | 56 (67%) | 8 (42%) |

| Game console a | n (%) | 58 (71%) | 11 (68%) | - | 62 (75%) | 13 (68%) |

| Number of media devices | Mean (sd) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.2) | - | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.2) |

| Media use frequency | ||||||

| Movies/series a | n (%) daily use | 47 (56%) | 11 (58%) | 43 (51%) | 11 (58%) | |

| Video games a | n (%) daily use | 37 (45%) | 8 (42%) | 45 (54%) | 6 (32%) | |

| Social media a | n (%) daily use | 32 (38%) | 5 (28%) | 34 (41%) | 7 (39%) | |

| Frequency of use (score) | Mean (sd) | 6.2 (3.3) | 5.1 (3.0) | - | 6.3 (2.9) | 5.3 (2.4) |

| Media Rules b | ||||||

| Movies/series | n (%) yes | 46 (66%) | 8 (53%) | - | 54 (77%) | 10 (67%) |

| Video games | n (%) yes | 49 (70%) | 6 (50%) | - | 50 (71%) | 10 (77%) |

| Social media | n (%) yes | 24 (50%) | 3 (38%) | - | 33 (69%) | 4 (50%) |

| Media use contract | n (%) yes | - | - | - | 66 (80%) | 0 (0%) |

| Objective knowledge | ||||||

| Number correct | Mean (sd) | 1.4 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.0) | 3.2 (0.8) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| Self-rated knowledge | ||||||

| Sum score | Mean (sd) | 18.0 (4.1) | 20.7 (2.7) | 21.8 (2.6) | 21.8 (2.2) | 19.2 (2.5) |

| Awareness | ||||||

| Sum score | Mean (sd) | 16.5 (2.4) | 16.7 (1.9) | 17.6 (1.9) | 17.6 (1.6) | 16.0 (1.9) |

| Class climate | ||||||

| Group work | n (%) very pleasant | 24 (29%) | - | 37 (44%) | - | - |

| Class climate | n (%) very good | 16 (19%) | - | 26 (31%) | - | - |

| T1 | T3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG-Info (n =26) | EG-Simple (n = 15) | CG (n = 14) | EG-Info (n =26) | EG-Simple (n = 15) | CG (n = 14) | ||

| Sex | n (%) female | 20 (73%) | 12 (80%) | 12 (86%) | 18 (69%) | 11 (73%) | 11 (79%) |

| n (%) male | 6 (23%) | 3 (20%) | 2 (14%) | 8 (31%) | 4 (27%) | 3 (21%) | |

| Education | |||||||

| Low/Middle | n (%) yes | 10 (38%) | 6 (40%) | 5 (38%) | - | - | - |

| Highest | n (%) yes | 16 (62%) | 9 (60%) | 8 (62%) | - | - | - |

| Media use frequency | |||||||

| Movies/series a | n (%) daily use | 11 (42%) | 7 (47%) | 4 (29%) | - | - | - |

| Video game a | n (%) daily use | 4 (15%) | 5 (33%) | 3 (21%) | - | - | - |

| Social media a | n (%) daily use | 18 (69%) | 13 (87%) | 10 (71%) | - | - | - |

| Frequency of use (score) | Mean (sd) | 5.2 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.4) | - | - | - |

| Discussion with child | |||||||

| Number topics | Mean (sd) | 3.3 (1.5) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.5) | 4.8 (0.7) | 4.4 (0.5) | 3.5 (1.6) |

| Confidence | |||||||

| Sum score | Mean (sd) | 9.6 (1.4) | 8.7 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.3) | 10.5 (1.3) | 10.0 (1.4) | 8.9 (1.3) |

| Variable | Difference EG-CG 1 | Differences Between Time Points | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In EG | In CG | ||||||

| t1 | t3 | t2-t1 2 | t3-t1 2 | t3-t2 3 | t3-t1 2 | ||

| Knowledge | b | −1.27 | 0.92 | 1.57 | 1.78 | 0.21 | −0.40 |

| 95% CI | −1.86, −0.69 | 0.36, 1.48 | 1.30, 1.85 | 1.50, 2.06 | −0.07, 0.48 | −1.08, 0.28 | |

| p | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.143 | 0.271 | |

| Perceived knowledge | b | −2.03 | 3.11 | 3.89 | 3.89 | 0.00 | −1.53 |

| 95% CI | −4.26, 0.20 | 1.97, 4.24 | 3.15, 4.23 | 3.16, 4.63 | −0.72, 0.73 | −2.56, −0.49 | |

| p | 0.078 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.994 | 0.010 | |

| Awareness | b | −0.10 | 1.65 | 1.17 | 1.11 | −0.06 | −0.66 |

| 95% CI | −1.26, 1.06 | 0.77, 2.53 | 0.66, 1.69 | 0.60, 1.62 | −0.56, 0.45 | −1.61, 0.30 | |

| p | 0.865 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.823 | 0.196 | |

| Class climate | OR | - | - | 2.49 | - | - | - |

| 95% CI | - | - | 1.01, 6.12 | - | - | - | |

| p | - | - | 0.046 | - | - | - | |

| Group work | OR | - | - | 2.65 | - | - | - |

| 95% CI | - | - | 1.16, 6.03 | - | - | - | |

| p | - | - | 0.021 | - | - | - | |

| Number devices | b | 0.40 | −0.11 | - | 0.19 | - | 0.33 |

| 95% CI | −0.29, 1.08 | −0.63, 0.41 | - | −0.02, 0.41 | - | 0.11, 0.56 | |

| p | 0.292 | 0.692 | - | 0.086 | - | 0.009 | |

| Frequency of use | b | 0.61 | 0.51 | - | 0.08 | - | −0.03 |

| 95% CI | −10.34, 20.56 | −0.67, 10.69 | - | −0.53, 0.69 | - | −0.98, 0.91 | |

| p | 0.538 | 0.399 | - | 0.794 | - | 0.949 | |

| Rules TV | OR | 2.38 | 1.55 | - | 2.93 | - | 2.80 |

| 95% CI | 0.57, 9.99 | 0.36, 6.72 | - | 0.95, 9.08 | - | 0.32, 24.7 | |

| p | 0.235 | 0.558 | - | 0.062 | - | 0.352 | |

| Rules video games | OR | 2.31 | 0.50 | - | 1.14 | - | 5.1 |

| 95% CI | 0.66, 8.06 | 0.09, 2.54 | - | 0.41, 3.09 | - | 0.65, 56.9 | |

| p | 0.189 | 0.405 | - | 0.799 | - | 0.141 | |

| Rules social media | OR | 2.01 | 1.30 | - | 2.95 | 1.91 | |

| 95% CI | 0.41, 9.90 | 0.24, 7.08 | - | 1.02, 8.55 | - | 0.19, 19.4 | |

| p | 0.391 | 0.764 | - | 0.047 | - | 0.583 | |

| Differences Between Groups 1 | Differences Between t1 and t3 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | t3 | |||||||

| EG-Info -CG | EG-Simple -CG | EG-Info -CG | EG-Simple -CG | EG-Info | EG-Simple | CG | ||

| Discussion with child | b | 0.19 | 0.44 | 1.10 | 0.67 | 1.40 | 0.85 | 0.43 |

| 95% CI | −0.73, 1.11 | −0.58, 1.46 | 0.62, 1.57 | 0.13, 1.22 | 0.93, 1.86 | 0.42, 1.29 | 0.09, 0.77 | |

| p | 0.689 | 0.400 | <0.001 | 0.019 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.028 | |

| Confidence | b | 1.49 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 1.33 | 0.64 |

| 95% CI | 0.23, 2.76 | −0.90, 1.83 | 0.10, 1.58 | 0.08, 1.64 | 0.36, 1.33 | 0.65, 2.01 | 0.08, 1.21 | |

| p | 0.052 | 0.527 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.045 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Poulain, T.; Kiess, W.; Drahtseil, T.; Meigen, C. Effects of a Media Prevention Program on Media-Related Knowledge and Awareness in Children and Their Parents: A Non-Randomized Controlled Cluster Study. Pediatr. Rep. 2026, 18, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010004

Poulain T, Kiess W, Drahtseil T, Meigen C. Effects of a Media Prevention Program on Media-Related Knowledge and Awareness in Children and Their Parents: A Non-Randomized Controlled Cluster Study. Pediatric Reports. 2026; 18(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulain, Tanja, Wieland Kiess, Team Drahtseil, and Christof Meigen. 2026. "Effects of a Media Prevention Program on Media-Related Knowledge and Awareness in Children and Their Parents: A Non-Randomized Controlled Cluster Study" Pediatric Reports 18, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010004

APA StylePoulain, T., Kiess, W., Drahtseil, T., & Meigen, C. (2026). Effects of a Media Prevention Program on Media-Related Knowledge and Awareness in Children and Their Parents: A Non-Randomized Controlled Cluster Study. Pediatric Reports, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric18010004