The Diversity of Developmental Age Gynecology—Selected Issues

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- 1.

- The number of admissions from 2012 to 2022 showed no significant upward or downward trend (r = 0.131, p > 0.05). The lowest number of admissions was recorded in 2020 (n = 299), possibly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the highest number occurred in 2022 (n = 612), indicating a potential backlog of cases being addressed post-pandemic (Table 1, Figure 1). No trend in the number of admissions was observed in the years 2013–2023 (no significant correlation, p > 0.05). Trend analysis was performed using Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient significance test (r values) and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient significance test (Rs values).

- 2.

- N94.0—Mittelschmerz (Intermenstrual pain)

- N94.1—Dyspareunia (Painful sexual intercourse)

- N94.2—Vaginismus

- N94.3—Premenstrual tension syndrome

- N94.4—Primary dysmenorrhea

- N94.5—Secondary dysmenorrhea

- N94.6—Unspecified dysmenorrhea

- N94.8—Other specified conditions associated with female genital organs and the menstrual cycle

- N94.9—Unspecified condition associated with female genital organs and the menstrual cycle

| Pelvic Pain Syndrome | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

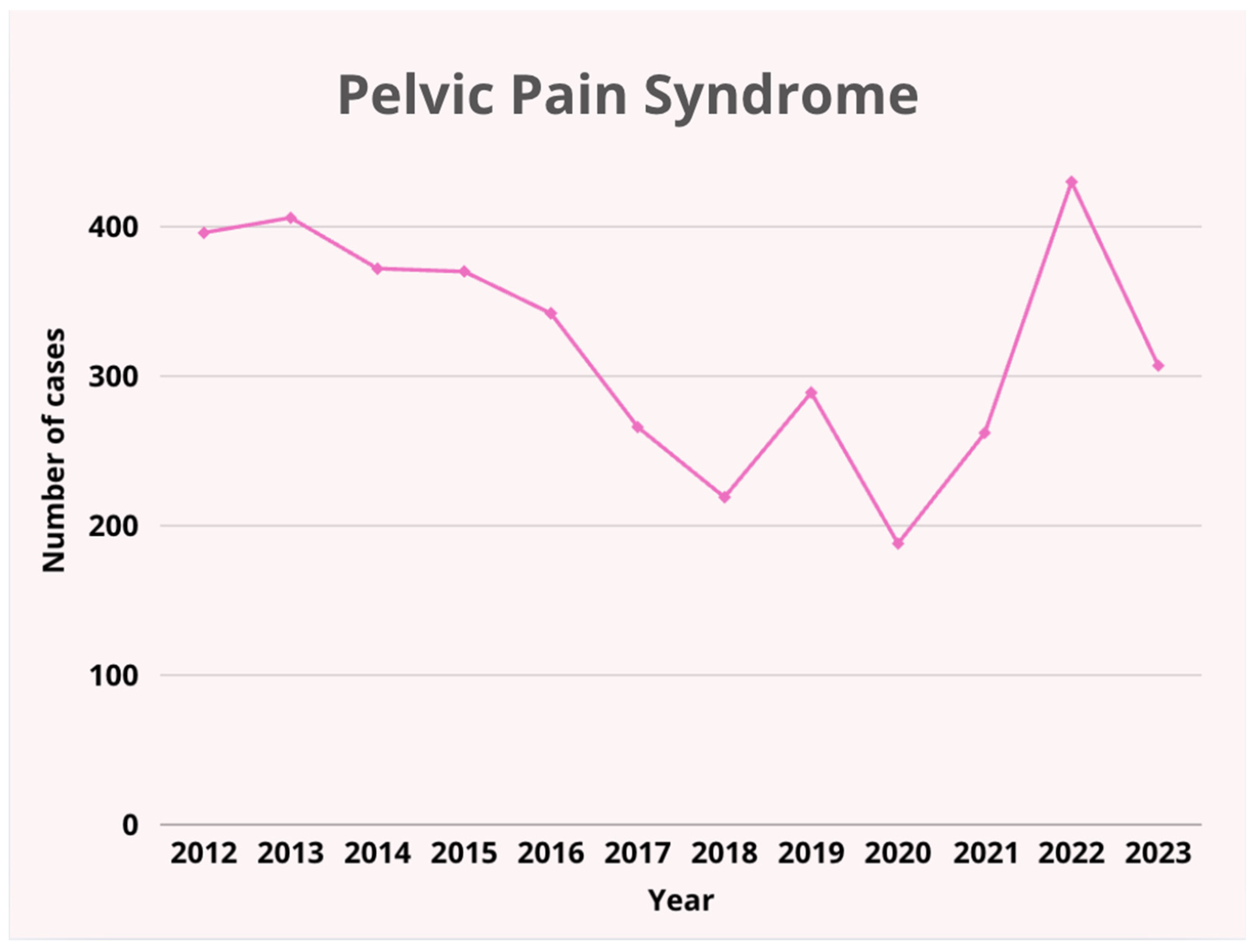

| Androgenization Syndromes | 396 | 406 | 372 | 370 | 342 | 266 | 219 | 289 | 188 | 262 | 430 | 307 | 3847 |

| Eating Disorders | 9 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 45 | 83 | 117 | 84 | 118 | 118 | 60 | 652 |

| Psychosexual Development Issues | 19 | 9 | 28 | 6 | 1 | 15 | 25 | 35 | 22 | 30 | 28 | 20 | 238 |

| Other | 8 | 35 | 22 | 26 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 36 | 42 | 192 |

| Total | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| 436 | 459 | 425 | 407 | 354 | 331 | 331 | 444 | 299 | 414 | 612 | 430 | 4942 |

- 3.

- Significant Correlations Between Years and the Percentage Share of Diagnoses

- (1)

- Androgenization Syndromes (p = 0.0040)—a strong positive correlation (Rs = 0.762). In the following years, the percentage share of this diagnosis among all diagnoses increased (upward trend).

- (2)

- Preventive Care, Issues Related to the Physiology and Pathology of the Mammary Glands, Osteoporosis, Pregnancy Planning Counselling, Contraception (p = 0.0471)—a moderate negative correlation (Rs = −0.582). Over the years, there was a decrease in the percentage share of this diagnosis among all diagnoses (downward trend).

- (3)

- Pelvic Pain Syndrome (p = 0.0018)—a strong negative correlation (Rs = −0.798). In the following years, the percentage share of this diagnosis among all diagnoses decreased (downward trend).

- 4.

- Diverse Conditions: While pelvic pain syndrome and androgenization syndromes dominate the diagnostic landscape, other conditions such as eating disorders, psychosexual issues, and breast pathology also play an important role. This underscores the need for a multidisciplinary approach in diagnosis and treatment, particularly in managing hormonal, psychosexual, and metabolic disorders.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medbook.com.pl. Słownik Pochodzenia nazw i Określeń Medycznych—Antyczne i Nowożytne Dzieje Chorób w ich Nazwach ukryte. Available online: https://medbook.com.pl/pl/nauki-pokrewne-medycyny/44402-slownik-pochodzenia-nazw-i-okreslen-medycznych-krzysztof-w-zielinski-hanna-zalewska-jura-16291.html?srsltid=AfmBOopQH5RqszD03dWxynCVv7dvAr4u9Ur_DTRKKYma2zzFGsLYe6M7 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Emans, Laufer, Goldstein’s Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology. Available online: https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/emans-laufer-goldsteins-pediatric--adolescent-gynecology-817 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Pelizzo, G.; Nakib, G.; Calcaterra, V. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology: Treatment Perspectives in Minimally Invasive Surgery. Pediatr. Rep. 2019, 11, 8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagens-Rotman, K.; Drejza, M.; Kędzia, W.; Jarząbek-Bielecka, G. Gynaecological Infections in Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology: A Review of Recommendations. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. /Postępy Dermatologii i Alergologii 2021, 38, 737–739. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Adolescent Health, ACOG. ACOG Committee Opinion. Number 335, May 2006: The initial reproductive health visit. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Z.J.; Rodriguez, P.; Wright, D.R.; Austin, S.B.; Long, M.W. Estimation of Eating Disorders Prevalence by Age and Associations with Mortality in a Simulated Nationally Representative US Cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Rebar, R.W.; Legro, R.S.; Balen, A.H.; Lobo, R.; Carmina, E.; Chang, J.; Yildiz, B.O.; Laven, J.S.E.; et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): The Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril. 2012, 97, 28–38.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witchel, S.F.; Burghard, A.C.; Tao, R.H.; Oberfield, S.E. The diagnosis and treatment of PCOS in adolescents: An update. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2019, 31, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.K.; Campbell, C.; Hansen, D.J. Child Sexual Abuse. In Handbook of Clinical Psychology Competencies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1481–1514. Available online: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-0-387-09757-2_54 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Mareti, E.; Vatopoulou, A.; Spyropoulou, G.A.; Papanastasiou, A.; Pratilas, G.C.; Liberis, A.; Hatzipantelis, E.; Dinas, K. Breast Disorders in Adolescence: A Review of the Literature. Breast Care 2020, 16, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sex Education in America. Available online: https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/sex-education-in-america-summary.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Hewitt, G.D.; Brown, R.T. Chronic Pelvic Pain in the Adolescent Differential Diagnosis and Evaluation. Available online: https://www.contemporaryobgyn.net/view/chronic-pelvic-pain-adolescent-differential-diagnosis-and-evaluation (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Jarząbek, G.; Kapczuk, K.; Pawlaczyk, M.; Sowińska-Przepiera, E.; Wachowiak-Ochmańska, K.; Szafińska, A.; Rzeczycki, J.; Friebe, Z.; Grys, E.; Bieś, Z.; et al. Problematyka ginekologii wieku rozwojowego na podstawie analizy dokumentacji lekarskiej poradni ginekologii i wieku rozwojowego. Now. Lek. 2003, 72, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Rocznik Demograficzny 2021. 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/demographic-yearbook-of-poland-2021,3,15.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Sytuacja Demograficzna Polski do 2022 roku. 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/population/population/demographic-situation-in-poland-up-to-2022,13,3.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Shukla, A.; Rasquin, L.I.; Anastasopoulou, C. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459251/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Meng, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Ma, C.; Shi, Q. Global burden of polycystic ovary syndrome among women of childbearing age, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis using the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1514250. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1514250/full (accessed on 12 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Christ, J.P.; Cedars, M.I. Current Guidelines for Diagnosing PCOS. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Nankali, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Jafarpour, S.; Ghasemi, H.; Dokaneheifard, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Women Worldwide: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, S.M.; Michala, L. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology: A multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 43, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, S.; Wood, P. A study of paediatric and adolescent gynaecology services in a British district general hospital. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 117, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L.S.; Chapin, J.L.; Lara-Torre, E.; Schulkin, J. The care of adolescents by obstetrician-gynecologists: A first look. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2009, 22, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaskowitz, A.; Quint, E. A Practical Overview of Managing Adolescent Gynecologic Conditions in the Pediatric Office. Pediatr. Rev. 2014, 35, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craighill, M.C. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology for the primary care pediatrician. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 1998, 45, 1659–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland Clinic. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology: What Primary Care Pediatricians Need to Know. Available online: https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/pediatric-and-adolescent-gynecology-what-primary-care-pediatricians-need-to-know (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Children′s National Hospital. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology for the Primary Care Provider. 6 October 2017. Available online: https://www.childrensnational.org/get-care/departments/pediatric-gynecology-program (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Braverman, P.K.; Breech, L.; The Committee on Adolescence. Gynecologic Examination for Adolescents in the Pediatric Office Setting. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, V.H.; Laube, D.W.; Hale, R.W.; Williams, S.B.; Power, M.L.; Schulkin, J. Obstetrician–Gynecologists and Primary Care: Training during Obstetrics–Gynecology Residency and Current Practice Patterns. Acad. Med. 2007, 82, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, W.W.; Barhan, S.M.; Rogers, R.E. Obstetrician-gynecologist as primary care provider. Am. J. Manag. Care 2001, 7, SP19–SP24. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, R.W. Obstetrician/Gynecologists: Primary Care Physicians for Women—ScienceDirect. Prim. Care Update Ob/Gyns. 1995, 2, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Weckmann, G.; Weckmann, F.; Jol, C.A. Women’s health in primary care—A comparative analysis of healthcare in 12 European countries|Request PDF. In Proceedings of the 28th World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) Europe Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 7–10 June 2023; ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371446106_Women’s_health_in_primary_care_-_a_comparative_analysis_of_healthcare_in_12_European_countries (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Rechenek-Białkowska, M.; Jarząbek-Bielecka, G.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; Lorkiewicz-Muszyńska, D.; Łabęcka, M.; Przystańska, A.; Obrebowska, A.; Pawlaczyk, M.; Jakubek, E.; Mizgier, M.; et al. Sexual violence against children, including the issue of STD and caring for their victims, also in mature age. Med. Rodz. 2022, 2022-1, 11–15. Available online: https://www.czytelniamedyczna.pl/7203,przemoc-seksualna-wobec-dzieci-z-uwzglednieniem-zagadnienia-std-i-opieki-nad-ofi.html (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Aspekty opiniowania lekarskiego w przypadku przemocy seksualnej wobec dzieci. Available online: https://www.czytelniamedyczna.pl/6610,aspekty-opiniowania-lekarskiego-w-przypadku-przemocy-seksualnej-wobec-dzieci.html (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Sachedin, A.; Todd, N.; Sachedin, A.; Todd, N. Dysmenorrhea, Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12, 7–17. Available online: https://jcrpe.org/articles/doi/jcrpe.galenos.2019.2019.S0217 (accessed on 12 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, K.; Sela, Y.; Nissanholtz-Gannot, R. New Insights about Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östberg, V.; Låftman, S.B.; Modin, B.; Lindfors, P. Bullying as a Stressor in Mid-Adolescent Girls and Boys-Associations with Perceived Stress, Recurrent Pain, and Salivary Cortisol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, S.S.; Bergman, S.; Almquist-Tangen, G.; Dahlgren, J.; Roswall, J.; Malmborg, J.S. Frequent Pain is Common Among 10-11-Year-Old Children with Symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 3867–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, M.A.; Nguyen, M.L. Psychosocial stress and abdominal pain in adolescents. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2010, 7, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Vallabhaneni, P. Anxiety disorders presenting as gastrointestinal symptoms in children—A scoping review. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2025, 68, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, T.; Fleming, N.; Tsampalieros, A.; Webster, R.J.; Black, A.; Mohammed, R.; Singh, S.S. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Practices: A National Survey of Canadian Gynecologists. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2022, 35, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.A.; Schroeder, B.; Kowalczyk, C. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology experience in academic and community OB/GYN residency programs in Michigan. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 1999, 12, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosdzol-Cop, A.; Orszulak, D. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology—Diagnostic and therapeutic trends. Ginekol. Pol. 2022, 93, 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms-Cendan, J. Examination of the pediatric adolescent patient. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 48, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, J.S.; Lara-Torre, E. Adolescent Gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemel, A.H. The Importance of Using Inclusive Language in Medical Practice. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health Blog. 2023. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjsrh/2023/03/31/the-importance-of-using-inclusive-language-in-medical-practice/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 6 Listopada 2008 r. o Prawach Pacjenta i Rzeczniku Praw Pacjenta. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20090520417 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Wilkes, M.S.; Anderson, M. A primary care approach to adolescent health care. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieving, R.E.; He, Y.; Lucas, S.; Brar, P.; O′BRien, J.R.G.; Gower, A.L.; Plowman, S.; Farris, J.; Ross, C.; Santelli, J.; et al. Primary Care Clinicians’ Views of Parents’ Roles in Clinical Preventive Services for Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2025, 39, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majcherek, E.; Jaskulska, J.; Drejza, M.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Kędzia, W.; Wilczak, M.; Pisarska-Krawczyk, M.; Mizgier, M.; Opydo-Szymaczek, J.; et al. The Diversity of Developmental Age Gynecology—Selected Issues. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050091

Majcherek E, Jaskulska J, Drejza M, Plagens-Rotman K, Kapczuk K, Kędzia W, Wilczak M, Pisarska-Krawczyk M, Mizgier M, Opydo-Szymaczek J, et al. The Diversity of Developmental Age Gynecology—Selected Issues. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(5):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajcherek, Ewa, Justyna Jaskulska, Michalina Drejza, Katarzyna Plagens-Rotman, Karina Kapczuk, Witold Kędzia, Maciej Wilczak, Magdalena Pisarska-Krawczyk, Małgorzata Mizgier, Justyna Opydo-Szymaczek, and et al. 2025. "The Diversity of Developmental Age Gynecology—Selected Issues" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 5: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050091

APA StyleMajcherek, E., Jaskulska, J., Drejza, M., Plagens-Rotman, K., Kapczuk, K., Kędzia, W., Wilczak, M., Pisarska-Krawczyk, M., Mizgier, M., Opydo-Szymaczek, J., Linke, J., Wójcik, M., & Jarząbek-Bielecka, G. (2025). The Diversity of Developmental Age Gynecology—Selected Issues. Pediatric Reports, 17(5), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050091