Subthreshold Autism and ADHD: A Brief Narrative Review for Frontline Clinicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

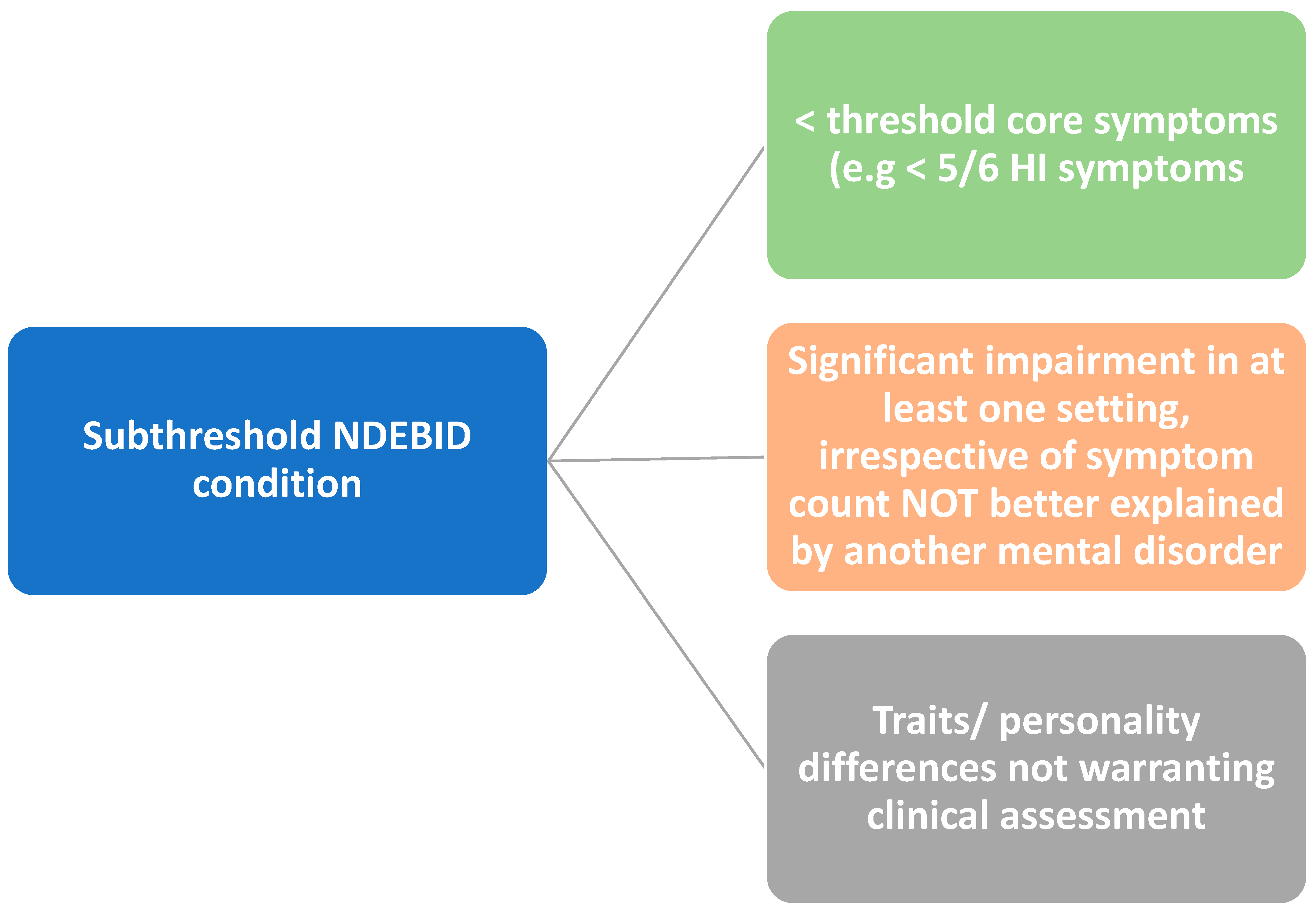

3.1. Definitions

3.2. Assessment Tools

3.3. Prevalence

3.4. Risk Factors and Neurobiology

3.5. Lifetime Functional Impairment

3.5.1. Cognitive and Academic Dysfunction

3.5.2. Psychosocial Difficulties

3.5.3. Crossing the Diagnostic Threshold

3.5.4. Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disorders

3.6. Review of NDD Classification Conceptual Models

3.6.1. Spectrum vs. Category

3.6.2. The Concept of Neurodiversity Rather than Disorder

3.7. Management

3.8. Raising Public Awareness

3.9. Future Research Directions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogundele, M.O.; Morton, M. Classification, prevalence and integrated care for neurodevelopmental and child mental health disorders: A brief overview for paediatricians. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillberg, C.; Fernell, E.; Minnis, H. Early symptomatic syndromes eliciting neurodevelopmental clinical examinations. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 710570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapar, A.; Cooper, M.; Rutter, M. Neurodevelopmental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embracing Complexity. Embracing Complexities in Diagnosis: Multi-Diagnostic Pathways for Neurodevelopmental Condi-tions. May 2019, p. 20. Available online: http://embracingcomplexity.org.uk/assets/documents/Embracing-Complexity-in-Diagnosis.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ayyash, H.F.; Ani, C.; Ogundele, M. The Role of Integrated Services in the Care of Children and Young People with Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Co-Morbid Mental Health Difficulties: An International Perspective. In Common Pediatric Diseases: Current Challenges; Rezaei, N., Samieefar, N., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2023; pp. 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, M.; Ayyash, H.; Ani, C. Integrated Services for Children and Young People with Neurodevelopmental and Co-Morbid Mental Health Disorders: Review of the Evidence. J. Psychiatry Ment. Disord. 2020, 5, 1027. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Luche, R.D.; Gesi, C.; Moroni, I.; Carmassi, C.; Maj, M. From Asperger’s Autistischen Psychopathen to DSM-5 Autism Spectrum Disorder and Beyond: A Subthreshold Autism Spectrum Model. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2016, 12, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmchen, H.; Linden, M. Subthreshold disorders in psychiatry: Clinical reality, methodological artifact, and the double-threshold problem. Compr. Psychiatry 2000, 41 (Suppl. S1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, H.A.; Davis, W.W.; McQueen, L.E. “Subthreshold” mental disorders. A review and synthesis of studies on minor depression and other “brand names”. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1999, 174, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Carpita, B.; Gesi, C.; Cremone, I.M.; Corsi, M.; Massimetti, E.; Muti, D.; Calderani, E.; Castellini, G.; Luciano, M.; et al. Subthreshold autism spectrum disorder in patients with eating disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 81, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meer, J.M.J.; Oerlemans, A.M.; Van Steijn, D.J.; Lappenschaar, M.G.A.; De Sonneville, L.M.J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Rommelse, N.N.J. Are Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Different Manifestations of One Overarching Disorder? Cognitive and Symptom Evidence From a Clinical and Population-Based Sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 1160–1172.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.; McGorry, P.D.; Wichers, M.; Wigman, J.T.W.; Hartmann, J.A. Moving From Static to Dynamic Models of the Onset of Mental Disorder: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; McGrath, M.J.; Viechtbauer, W.; Kuppens, P. Dimensions over categories: A meta-analysis of taxometric research. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1418–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblond, C.S.; Rolland, T.; Barthome, E.; Mougin, Z.; Fleury, M.; Ecker, C.; Bonnot-Briey, S.; Cliquet, F.; Tabet, A.-C.; Maruani, A.; et al. A Genetic Bridge Between Medicine and Neurodiversity for Autism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2024, 58, 487–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.R.; Gardiner, E.; Harding, L. Behavioural and emotional concerns reported by parents of children attending a neurodevelopmental diagnostic centre. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundele, M.O. A Profile of Common Neurodevelopmental Disorders Presenting in a Scottish Community Child Health Service—A One Year Audit (2016/2017). Health Res. 2018, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, J.; Keresztény, A. Subthreshold attention deficit hyperactivity in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Kirova, A.-M.; Woodworth, K.Y.; Biederman, I.; Faraone, S.V. Further Evidence of Morbidity and Dysfunction Associated With Subsyndromal ADHD in Clinically Referred Children. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79, 17m11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Lorenzi, P.; Carpita, B. Autistic Traits and Illness Trajectories. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2019, 15, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Cordone, A.; Ciapparelli, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Barberi, F.M.; Foghi, C.; Pedrinelli, V.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bazzichi, L.; Dell’Osso, L. Adult Autism Subthreshold spectrum correlates to Post-traumatic Stress Disorder spectrum in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. 130), 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Gesi, C.; Massimetti, E.; Cremone, I.M.; Barbuti, M.; Maccariello, G.; Moroni, I.; Barlati, S.; Castellini, G.; Luciano, M.; et al. Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum): Validation of a questionnaire investigating subthreshold autism spectrum. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 73, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, M.A.; Berrocal, C.; Primi, C.; Petracchi, G.; Carpita, B.; Cosci, F.; Ruiz, A.; Carmassi, C.; Dell’Osso, L. Measuring subthreshold autistic traits in the general population: Psychometric properties of the Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum) scale. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Cremone, I.M.; Chiarantini, I.; Arone, A.; Massimetti, G.; Carmassi, C.; Carpita, B. Autistic traits and camouflaging behaviors: A cross-sectional investigation in a University student population. CNS Spectr. 2022, 27, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanne, S.M.; Wang, J.; Christ, S.E. The Subthreshold Autism Trait Questionnaire (SATQ): Development of a brief self-report measure of subthreshold autism traits. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Panagiotidis, P.; Kimiskidis, V.; Nimatoudis, I.; Gonda, X. Prevalence and correlates of neurological soft signs in healthy controls without family history of any mental disorder: A neurodevelopmental variation rather than a specific risk factor? Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Neurosci. 2018, 68, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, K.; Edbom, T.; Wargelius, H.-L.; Larsson, J.-O. Psychiatric problems associated with subthreshold ADHD and disruptive behaviour diagnoses in teenagers. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamio, Y.; Moriwaki, A.; Takei, R.; Inada, N.; Inokuchi, E.; Takahashi, H.; Nakahachi, T. [Psychiatric issues of children and adults with autism spectrum disorders who remain undiagnosed]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2013, 115, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gökçen, E.; Petrides, K.V.; Hudry, K.; Frederickson, N.; Smillie, L.D. Sub-threshold autism traits: The role of trait emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Carpita, B.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Diadema, E.; Barberi, F.M.; Gesi, C.; Carmassi, C. Subthreshold autism spectrum in bipolar disorder: Prevalence and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robel, L.; Rousselot-Pailley, B.; Fortin, C.; Levy-Rueff, M.; Golse, B.; Falissard, B. Subthreshold traits of the broad autistic spectrum are distributed across different subgroups in parents, but not siblings, of probands with autism. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arildskov, T.W.; Højgaard, D.R.M.A.; Skarphedinsson, G.; Thomsen, P.H.; Ivarsson, T.; Weidle, B.; Melin, K.H.; Hybel, K.A. Subclinical autism spectrum symptoms in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, A.; Craig, F.; Palermo, G.; Coppola, A.; Margari, M.; Campanozzi, S.; Margari, L.; Turi, M. Differential Diagnosis in Children with Autistic Symptoms and Subthreshold ADOS Total Score: An Observational Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamaño, M.; Boada, L.; Merchán-Naranjo, J.; Moreno, C.; Llorente, C.; Moreno, D.; Arango, C.; Parellada, M. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with ASD without mental retardation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2442–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirova, A.-M.; Kelberman, C.; Storch, B.; DiSalvo, M.; Woodworth, K.Y.; Faraone, S.V.; Biederman, J. Are subsyndromal manifestations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder morbid in children? A systematic qualitative review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 274, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ek, U.; Fernell, E.; Westerlund, J.; Holmberg, K.; Olsson, P.-O.; Gillberg, C. Cognitive strengths and deficits in schoolchildren with ADHD. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, H.; Anckarsater, H.; Råstam, M.; Chang, Z.; Lichtenstein, P. Childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as an extreme of a continuous trait: A quantitative genetic study of 8,500 twin pairs. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.-C.; Kim, B.-N.; Kim, J.-W.; Rohde, L.A.; Hwang, J.-W.; Chungh, D.-S.; Shin, M.-S.; Lyoo, I.K.; Go, B.-J.; Lee, S.-E.; et al. Full syndrome and subthreshold attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a Korean community sample: Comorbidity and temperament findings. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyad, J.; Sampson, N.A.; Hwang, I.; Adamowski, T.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.H.S.G.; Borges, G.; de Girolamo, G.; Florescu, S.; et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2017, 9, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidt, A.; Höhnle, N.M.; Schönenberg, M. Cognitive and electrophysiological markers of adult full syndrome and subthreshold attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 127, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-B.; Dwyer, D.; Kim, J.-W.; Park, E.-J.; Shin, M.-S.; Kim, B.-N.; Yoo, H.-J.; Cho, I.-H.; Bhang, S.-Y.; Hong, Y.-C.; et al. Subthreshold attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is associated with functional impairments across domains: A comprehensive analysis in a large-scale community study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Prime, H.; Madigan, S. Using Sibling Designs to Understand Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Genes and Environments to Prevention Programming. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 672784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Asherson, P.; Viding, E.; Greven, C.U.; Pingault, J.-B. Early Predictors of De Novo and Subthreshold Late-Onset ADHD in a Child and Adolescent Cohort. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecendreux, M.; Silverstein, M.; Konofal, E.; Cortese, S.; Faraone, S.V. A 9-Year Follow-Up of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in a Population Sample. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 18m12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, J.F.; McClellan, L.S.; Li, S.; Jack, A.E.; Wallace, G.L.; McQuaid, G.A.; Kenworthy, L.; Anthony, L.G.; Lai, M.-C.; Pelphrey, K.A.; et al. The autism spectrum among transgender youth: Default mode functional connectivity. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 6633–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, W.E.; Wolke, D.; Shanahan, L.; Costello, E.J. Adult Functional Outcomes of Common Childhood Psychiatric Problems: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostoli, S.; Raimondi, G.; Gremigni, P.; Rafanelli, C. Subclinical attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Li, H.; Si, F.; Zhao, M.; Dong, M.; Pan, M.; Yue, X.; Liu, L.; Qian, Q.; et al. The Clinical Manifestation, Executive Dysfunction, and Caregiver Strain in Subthreshold Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankman, S.A.; Lewinsohn, P.M.; Klein, D.N.; Small, J.W.; Seeley, J.R.; Altman, S.E. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: A 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, J.L.; Gaffrey, M.S.; Tillman, R.; April, L.M.; Belden, A.C. Trajectories of preschool disorders to full DSM depression at school age and early adolescence: Continuity of preschool depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, S.E.; Kanne, S.M.; Reiersen, A.M. Executive function in individuals with subthreshold autism traits. Neuropsychology 2010, 24, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, N.; Virta, M.; Leppämäki, S.; Launes, J.; Vanninen, R.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Immonen, S.; Järvinen, I.; Lehto, E.; Michelsson, K.; et al. ADHD and subthreshold symptoms in childhood and life outcomes at 40 years in a prospective birth-risk cohort. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendarski, N.; Guo, S.; Sciberras, E.; Efron, D.; Quach, J.; Winter, L.; Bisset, M.; Middeldorp, C.M.; Coghill, D. Examining the Educational Gap for Children with ADHD and Subthreshold ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussing, R.; Mason, D.M.; Bell, L.; Porter, P.; Garvan, C. Adolescent outcomes of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a diverse community sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washbrook, E.; Propper, C.; Sayal, K. Pre-school hyperactivity/attention problems and educational outcomes in adolescence: Prospective longitudinal study. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2013, 203, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, N.; Virta, M.; Leppämäki, S.; Launes, J.; Vanninen, R.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Järvinen, I.; Lehto, E.; Hokkanen, L. Childhood ADHD and subthreshold symptoms are associated with cognitive functioning at age 40-a cohort study on perinatal birth risks. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1393642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirama, A.; Stickley, A.; Kamio, Y.; Saito, A.; Haraguchi, H.; Wada, A.; Sueyoshi, K.; Sumiyoshi, T. Emotional and behavioral problems in Japanese preschool children with subthreshold autistic traits: Findings from a community-based sample. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, L.D.; Tian, L.H.; Rubenstein, E.; Schieve, L.; Daniels, J.; Pazol, K.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Barger, B.; Moody, E.; Rosenberg, S.; et al. Features that best define the heterogeneity and homogeneity of autism in preschool-age children: A multisite case-control analysis replicated across two independent samples. Autism Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, B.; Li, S.; Li, P.; Yang, L. Time perception of individuals with subthreshold autistic traits: The regulation of interpersonal information associations. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Akechi, T. The mediating role of psychological flexibility in the association of autistic-like traits with burnout and depression in medical students during clinical clerkships in Japan: A university-based cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, A.I.; Luman, M.; van der Oord, S.; Bergwerff, C.E.; van den Hoofdakker, B.J.; Oosterlaan, J. Facial emotion recognition impairment predicts social and emotional problems in children with (subthreshold) ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.; Hammerton, G.; Collishaw, S.; Langley, K.; Thapar, A.; Dalsgaard, S.; Stergiakouli, E.; Tilling, K.; Davey Smith, G.; Maughan, B.; et al. Investigating late-onset ADHD: A population cohort investigation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.B.; Munir, K.; Munafò, M.R.; Hughes, M.; McCormick, M.C.; Koenen, K.C. Stability of autistic traits in the general population: Further evidence for a continuum of impairment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, C.W.; Sigman, M. Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Stickley, A.; Haraguchi, H.; Takahashi, H.; Ishitobi, M.; Kamio, Y. Association Between Autistic Traits in Preschool Children and Later Emotional/Behavioral Outcomes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3333–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Carpita, B.; Muti, D.; Morelli, V.; Salarpi, G.; Salerni, A.; Scotto, J.; Massimetti, G.; Gesi, C.; Ballerio, M.; et al. Mood symptoms and suicidality across the autism spectrum. Compr. Psychiatry 2019, 91, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, J.; Kamio, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Ota, M.; Teraishi, T.; Hori, H.; Nagashima, A.; Takei, R.; Higuchi, T.; Motohashi, N.; et al. Autistic-Like Traits in Adult Patients with Mood Disorders and Schizophrenia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyku Memis, C.; Sevincok, D.; Dogan, B.; Baygin, C.; Ozbek, M.; Kutlu, A.; Cakaloz, B.; Sevincok, L. The subthreshold autistic traits in patients with adult-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparative study with adolescent patients. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 54, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norén Selinus, E.; Molero, Y.; Lichtenstein, P.; Anckarsäter, H.; Lundström, S.; Bottai, M.; Hellner Gumpert, C. Subthreshold and threshold attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in childhood: Psychosocial outcomes in adolescence in boys and girls. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2016, 134, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, R. ADHD symptomatology is best conceptualized as a spectrum: A dimensional versus unitary approach to diagnosis. Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2015, 7, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; Rutter, M. Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Conceptual Issues. In Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, C.J.; Klein, C. Comorbidity of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Current Status and Promising Directions. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 57, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. Nativism versus neuroconstructivism: Rethinking the study of developmental disorders. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, N.; Mynors-Wallis, L. Psychiatric diagnosis: Impersonal, imperfect and important. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2014, 204, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, B.N. Research Domain Criteria: Toward future psychiatric nosologies. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 17, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J.; Wylie, G.; Haig, C.; Gillberg, C.; Minnis, H. Towards system redesign: An exploratory analysis of neurodivergent traits in a childhood population referred for autism assessment. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne’eman, A. When Disability Is Defined by Behavior, Outcome Measures Should Not Promote “Passing”. AMA J. Ethics 2021, 23, E569–E575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, N. Neurodiversity at work: A biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 135, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.S.; Deeley, Q. Dangers of self-diagnosis in neuropsychiatry. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoopen, L.W.; de Nijs, P.F.; Slappendel, G.; van der Ende, J.; Bastiaansen, D.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L.; Hillegers, M.H. Associations between autism traits and family functioning over time in autistic and non-autistic children. Autism Int. J. Res. Pract. 2023, 27, 2035–2047. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.I. Efficacy of Omega-3 and Korean Red Ginseng in Children with Subthreshold ADHD: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundele, M.O.; Ayyash, H.F. ADHD in children and adolescents: Review of current practice of non-pharmacological and behavioural management. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garralda, M.E. Child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and ICD-11. Br. J. Psychiatry 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Z.D.; Gowda, A.; Horsfall Turner, I.C. The viability of a proposed psychoeducational neurodiversity approach in children services: The PANDA (the Portsmouth alliance’s neuro-diversity approach). Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosco, J.P.; Bona, A. Changes in Academic Demands and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Young Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaschewski, T.; Häge, A.; Hohmann, S.; Mechler, K. Perspectives on ADHD in children and adolescents as a social construct amidst rising prevalence of diagnosis and medication use. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1289157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falissard, B. Did we take the right train in promoting the concept of “Neurodevelopmental disorders”? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekori-Domachevsky, E.; Guri, Y.; Yi, J.; Weisman, O.; Calkins, M.E.; Tang, S.X.; Gross, R.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Emanuel, B.S.; Zackai, E.H.; et al. Negative subthreshold psychotic symptoms distinguish 22q11.2 deletion syndrome from other neurodevelopmental disorders: A two-site study. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 188, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, L.; Boot, E.; Bassett, A.S. Update on the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and its relevance to schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Osa, N.; Penelo, E.; Navarro, J.B.; Trepat, E.; Ezpeleta, L. Prevalence, comorbidity, functioning and long-term effects of subthreshold oppositional defiant disorder in a community sample of preschoolers. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Population | ADHD Traits | ASD Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| [35] Ek et al., 2007 | General population | 1.6% | |

| [37] Cho et al., 2009 | Korean school children | 9% | |

| [36] Larsson et al., 2012 | 9–12 yr Swedish twins | 9.75% | |

| [17] Balázs & Keresztény | LR | 0.8–23.1% | |

| [31] Arildskov et al., 2016 | OCD | 10–17% | |

| [38] Fayyad et al., 2016 | Adults | 3.7% | |

| [34] Kirova et al., 2019 | LR/Meta-analysis | 17.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogundele, M.O.; Morton, M.J.S. Subthreshold Autism and ADHD: A Brief Narrative Review for Frontline Clinicians. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020042

Ogundele MO, Morton MJS. Subthreshold Autism and ADHD: A Brief Narrative Review for Frontline Clinicians. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgundele, Michael O., and Michael J. S. Morton. 2025. "Subthreshold Autism and ADHD: A Brief Narrative Review for Frontline Clinicians" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020042

APA StyleOgundele, M. O., & Morton, M. J. S. (2025). Subthreshold Autism and ADHD: A Brief Narrative Review for Frontline Clinicians. Pediatric Reports, 17(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020042