Facts and Recommendations regarding When Medical Institutions Report Potential Abuse to Child Guidance Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Facilities

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Items

2.3.1. Basic Attributes of Facilities

2.3.2. Notification Policy

2.3.3. Reason for Notification Policy

2.3.4. Effects of the Notification

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate and Basic Attributes of Responding Facilities and Respondents

3.2. Response Rate and Basic Attributes of Responding Facilities and Respondents

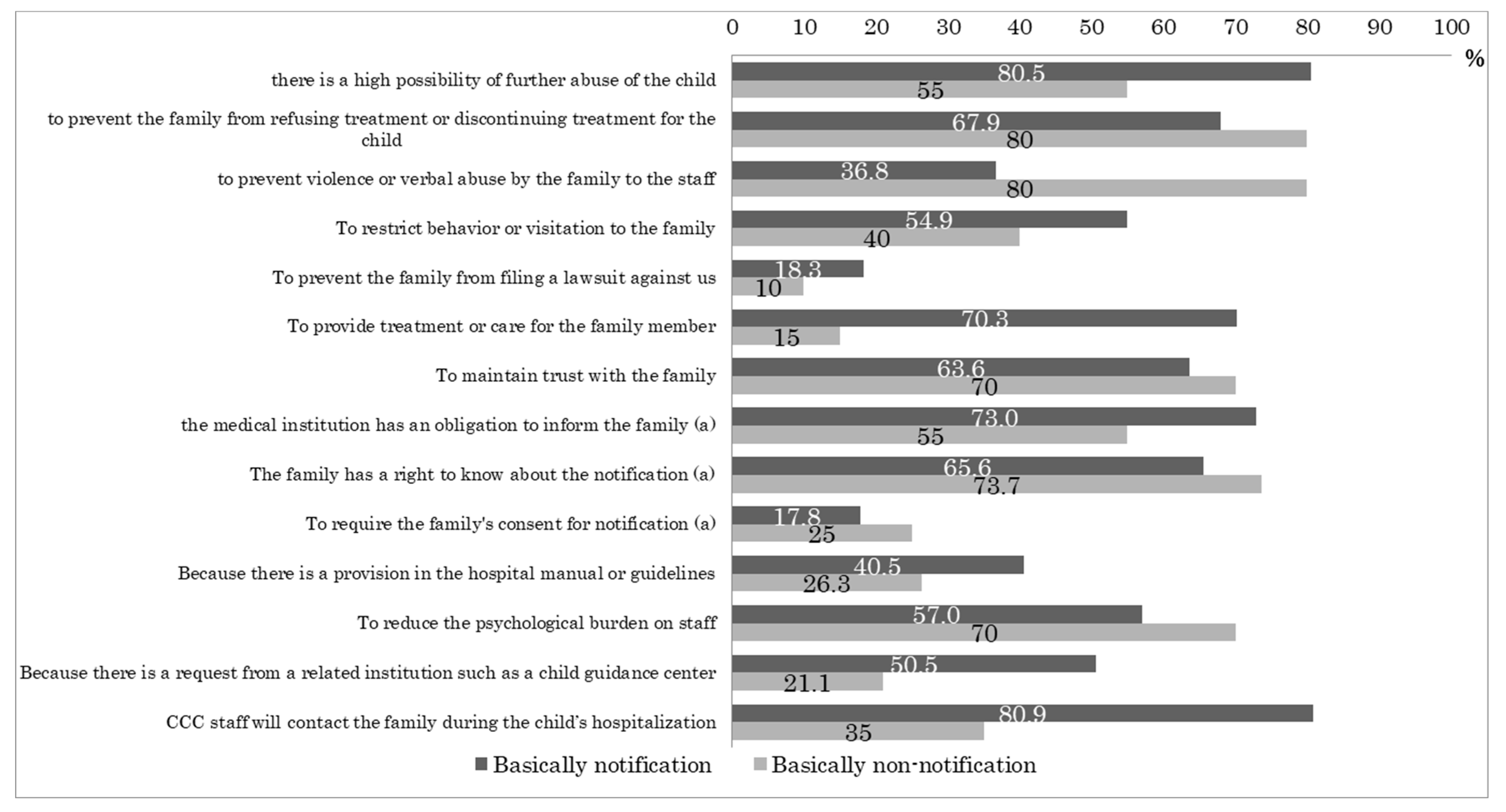

3.3. Reasons for the Notification Policy

3.4. Effects of Notification

3.4.1. Experienced Difficulties after Responding to Notifications

3.4.2. Notification Policy and Experienced Difficulties

3.4.3. Timing of Notification and Experienced Difficulties

3.4.4. Psychological Burden of Dealing with Family Members

4. Discussion

4.1. Notification Policy and Reasons

4.2. Difficulties Arising with Notification and Non-Notification

4.3. Difficulties Arising and Timing of Notification

4.4. Psychological Burden of Dealing with Family Members

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teo, S.S.S.; Griffiths, G. Child protection in the time of COVID-19. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 146, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.; Ming, D.; Maslow, G.; Gifford, E. Mitigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic response on at-risk children. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yomiuri Shimbun. Jido-Gyakutai Saita-no 108,050-nin, Corona de Senzaika no Osore “Ie ni Irushika-Naku Oya no Boryoku Hidokunatta [The Largest Number of Child Abuse, 108,050, Is Feared to be Latent in COVID-19, “I Had No Choice but to Stay at Home and the Parental Violence Got Worse.”]. 3 February 2022. Available online: https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/national/20220203-OYT1T50179/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Jiji Tsushin. Jido-Gyakutai-Higai, SAITA 2,219-nin: Corona de Senzaika-Kenen, Sakunen 54-nin Shibo, Keisatsucho [Child Abuse Victims, the Largest Number of 2219 People: 54 Deaths Last Year in the Covid-19, National Police Agency]. 10 March 2022. Available online: https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2022031000430&g=soc (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Act on the Prevention, etc. of Child Abuse. Act No. 82 of 24 May 2000. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/2221/tb (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Japan. Jido no Kenri ni kansuru Joyaku [Convention on the Rights of the Child]. 1994. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/kokusai/jidou/main4_a9.htm (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1990. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- McCoy, M.L.; Keen, S.M. Child Abuse and Neglect, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2009; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. The Role if Professional Child Care Providers in Preventing and Responding to Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008. Available online: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/childcare.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Kitaoka, T. Tsukoku to Kokuchi: Nani wo Dou Tsutaeru ka [Notification and report: What to say and how to say it]. Shoni Naika 2010, 42, 1854–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Kliegman, R.M.; Bonita, M.D.; Joseph, S.; Geme, S.; Schor, N.F.; Behrman, R.E. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, S.E. Child Abuse: Clinical Findings and Management. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2000, 12, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HM Government. Working Together to Safeguard Children—A Guide to Inter-Agency Working to Safeguard and Promote the Welfare of Children. 2010. Available online: https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/publicationdetail/page1/DCSF-00305-2010 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- General Medical Council, Protecting Children and Young People. The Responsibilities of All Doctors. 2012. Available online: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/13260.asp (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Besharov, D.J. Recognizing Child Abuse a Guide For The Concerned; FreePress: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, C. Safeguarding and Child Protection for Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors. A Practical Guide; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman, S.C. Mandated Reporting of Suspected Child Abuse. Ethics, Law, & Policy, 2nd ed.; Amer Psychological Assn: Worcester, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- London Safeguarding Children Board. London Child Protection Procedures and Practice Guidance; London Safeguarding Children Board: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M. Jido-dodanjo kara mita Chiiki-iryo-network ni tsuite no Ankeito Chosa: Hi-gyakutaiji ni taio surutameno Byoin-nai oyobi Chiiki-iryo-system ni kansuru Kenkyu [Questionnaire Survey on Community Medical Network from the Viewpoint of Child Consultation Center: Study on Hospital and Community Medical System for Responding to Abused Children]. FY2004 Health, Labour and Welfare Science Research (Comprehensive Research Project for Children and Families) Study on the Comprehensive Medical Treatment System for Abused Children (Principal Investigator: Toshiro Sugiyama). FY2004 Res. Rep. 2004, 11–39. Available online: https://mhlw-grants.niph.go.jp/system/files/2004/043031/200400386A/200400386A0001.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Nakamura, Y.; Kitano, N. Kodomo Gyakutai no Kokusai-hikaku [International Comparison of Child Abuse]. Shoni Naika 2011, 42, 1754–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, F. Jido-Gyakutai: Genba Kara no Teigen [Child Abuse: Recommendations from the Field]; Iwanami Shinsho: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhnke, G.W.; Wilson, S.R.; Akamatsu, T.; Kinoue, T.; Takashima, Y.; Goldstein, M.K.; Koenig, B.A.; Hornberger, J.C.; Raffin, T.A. Ethical decision making and patient autonomy: A comparison of physicians and patients in Japan and the United States. Chest 2000, 118, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford University School of Medicine. Disclosing—Child Abuse. Available online: http://childabuse.stanford.edu/reporting/disclosing.html (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Hayasaka, Y. Daigaku byion no Baai: CAPS (Child Abuse Prevention System) [For University Hospitals: CAPS (Child Abuse Prevention System)]. Shoni Naika 2011, 42, 1844–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Pediatric Society. Kodomo Gyakutai Shinryo Tebiki Dai-2-han [A Guide to the Treatment of Child Abuse, 2nd ed.]. 2014. Available online: http://www.jpeds.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=25 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Hospital Type | |

| Children’s hospital | 14 (4.4) |

| University hospital | 81 (25.6) |

| General hospital | 217 (68.7) |

| Other | 4 (1.3) |

| Hospital Location | |

| Hokkaido | 18 (5.7) |

| Tohoku | 18 (5.7) |

| Kanto | 87 (27.4) |

| Chubu | 68 (21.5) |

| Kinki | 69 (21.8) |

| Chugoku | 14 (4.4) |

| Shikoku | 12 (3.8) |

| Kyushu | 31 (9.8) |

| Total Number of Beds | |

| ≤249 beds | 20 (6.5) |

| 250–499 beds | 105 (34.3) |

| 500–749 beds | 120 (39.2) |

| 750–999 beds | 36 (11.8) |

| 1000 beds | 25 (8.2) |

| Pediatric Beds | |

| ≤24 beds | 104 (33.6) |

| 25–49 beds | 150 (48.4) |

| 50–74 beds | 39 (12.6) |

| 75–99 beds | 5 (1.6) |

| 100 beds | 12 (3.9) |

| Report Experience | |

| Yes | 278 (88.8) |

| No experience | 35 (11.2) |

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 252 (79.5) |

| Female | 65 (20.5) |

| Occupation | |

| Doctor | 296 (93.4) |

| Nurse | 18 (5.7) |

| Social worker | 2 (0.6) |

| Clinical psychologist | 1 (0.3) |

| Position Related to Child Abuse Cases a | |

| Yes | 217 (70.2) |

| Not employed | 92 (29.8) |

| Average (min., max.) | |

| Age | 49.3 (28, 66) |

| Years of experience in the profession | 23.7 (2, 41) |

| Years involved in dealing with child abuse cases child abuse child abuse | 9.7 (0, 37) |

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Notification Policy | |

| Notification | 190 (59.8) |

| Varies from case to case | 107 (33.7) |

| No notification | 21 (6.6) |

| Number of Cases Notified in a Year | |

| 0 cases | 94 (30.6) |

| 1–5 cases | 168 (54.7) |

| 6–10 cases | 31 (10.1) |

| 11–15 | 8 (2.6) |

| 16 cases | 6 (2.0) |

| Number of Notices per Year | |

| 0 | 122 (40.5) |

| 1–5 | 141 (46.8) |

| 6–10 | 25 (8.3) |

| 11–15 notices | 7 (2.3) |

| 16 notices | 6 (2.0) |

| In Case of Notificationn (%) | In Case of Non-Notificationn (%) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 278 (100) | 278 (100) | |

| Experienced some kind of problem † | 176 (63.3) | 52 (18.7) | <001 |

| Content of Problems Experienced (multiple responses allowed) | |||

| Relationship with family deteriorated | 143 (51.4) | 25 (9.0) | |

| Family requested early discharge or transfer | 80 (28.8) | 14 (5.0) | |

| Family refused treatment for the child | 39 (14.0) | 9 (3.2) | |

| Family was violent toward the staff or harmed the staff in some other way | 38 (13.7) | 8 (2.9) | |

| The family removed or attempted to remove the child | 38 (13.7) | 6 (2.2) | |

| The child suffered further abuse | 10 (3.6) | 19 (6.8) | |

| The family filed a lawsuit | 7 (2.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Notification Group | Case-by-Case group Notification | p-Value * | Non-Notification Group | Case-by-Case group Non-notification | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 172 (100) | 87 (100) | 18 (100) | 87 (100) | ||

| Experienced some kind of problem † | 102 (59.3) | 65 (74.7) | 0.015 | 2 (11.1) | 30 (34.5) | 0.050 |

| Content of Problems Experienced (multiple responses allowed) | ||||||

| Relationship with family deteriorated | 79 (45.9) | 56 (64.4) | 0 (0) | 13 (14.9) | ||

| Family requested early discharge or transfer | 43 (25.0) | 31 (35.6) | 1 (5.6) | 9 (10.3) | ||

| Family refused treatment for the child | 15 (8.7) | 18 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.6) | ||

| Family was violent toward the staff or harmed the staff in some other way | 22 (12.8) | 13 (14.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.6) | ||

| The family removed or attempted to remove the child | 17 (9.8) | 18 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.6) | ||

| The child suffered further abuse | 6 (3.5) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (5.6) | 10 (11.5) | ||

| The family filed a lawsuit | 3 (1.7) | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Pre-Report n (%) | Post-Report n (%) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 73 (100) | 67 (100) | |

| Experienced some kind of problem † | 40 (54.8) | 52 (77.6) | 0.005 |

| Content of Problems Experienced (multiple responses allowed) | |||

| Relationship with family deteriorated | 30 (41.1) | 42 (62.7) | |

| Family requested early discharge or transfer | 16 (21.9) | 20 (29.9) | |

| Family refused treatment for the child | 4 (5.5) | 6 (9.0) | |

| Family was violent toward the staff or harmed the staff in some other way | 6 (8.2) | 11 (16.4) | |

| The family removed or attempted to remove the child | 3 (4.1) | 11 (16.4) | |

| The child suffered further abuse | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.5) | |

| The family filed a lawsuit | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urade, M.; Fujita, M.; Tsuchiya, A.; Mori, K.; Nakazawa, E.; Takimoto, Y.; Akabayashi, A. Facts and Recommendations regarding When Medical Institutions Report Potential Abuse to Child Guidance Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 14, 479-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric14040056

Urade M, Fujita M, Tsuchiya A, Mori K, Nakazawa E, Takimoto Y, Akabayashi A. Facts and Recommendations regarding When Medical Institutions Report Potential Abuse to Child Guidance Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatric Reports. 2022; 14(4):479-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric14040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrade, Mio, Misao Fujita, Atsushi Tsuchiya, Katsumi Mori, Eisuke Nakazawa, Yoshiyuki Takimoto, and Akira Akabayashi. 2022. "Facts and Recommendations regarding When Medical Institutions Report Potential Abuse to Child Guidance Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study" Pediatric Reports 14, no. 4: 479-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric14040056

APA StyleUrade, M., Fujita, M., Tsuchiya, A., Mori, K., Nakazawa, E., Takimoto, Y., & Akabayashi, A. (2022). Facts and Recommendations regarding When Medical Institutions Report Potential Abuse to Child Guidance Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatric Reports, 14(4), 479-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric14040056