1. Introduction

Fungi are a crucial source of bioactive compounds, possessing a remarkable biosynthetic capacity for producing compounds with novel chemical structures [

1]. Historically, the study of these compounds catalyzed the golden age of antibiotic discovery, leading to the identification of most antibiotics still utilized today. The first antibiotic, penicillin, discovered in 1929, was isolated from a fungal species. Penicillin has fundamentally transformed the treatment of bacterial infections, resulting in substantial advances in public health and medical practice [

2]. Pleuromutilins, a class of antibiotics derived from macrofungi, were identified in the 1950s. Recently, a pleuromutilin derivative, retapamulin, has been approved for human use in the topical treatment of impetigo and minor wounds infected by

Staphylococcus aureus. Another derivative, lefamulin, has recently progressed to the final clinical phase for treatment of pneumonia and skin infections [

3].

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive, spherical (coccus) bacterium that typically clusters [

4]. While present in healthy humans, it can cause skin infections and serious conditions, such as endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, and pneumonia, in internal tissues [

5,

6].

Staphylococcus aureus infections are complicated by antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Methicillin-resistant

S. aureus (MRSA) in hospitals and communities has rendered many antibiotics ineffective, thereby increasing global mortality rates [

4]. In 2021, MRSA caused over 130,000 fatalities [

7], leading the World Health Organization to prioritize it for new treatment development [

8]. Previous studies have indicated that mortality rates associated with MRSA can reach as high as 60%. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 323,700 MRSA infections in US hospitals, causing 10,600 deaths and

$1.7 billion USD in costs [

9]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the incidence of infections caused by vancomycin-resistant

S. aureus (VRSA). Vancomycin remains a last-resort treatment option with associated health risks [

4]. Consequently, the exploration of strategies to combat drug-resistant bacteria has become an urgent priority. The development of novel antibiotics remains a crucial strategy for addressing AMR. Nonetheless, there is a growing interest in the advancement of alternative therapeutic approaches, including: (1) anti-virulence drugs targeting virulence factors to reduce disease severity and (2) adjuvants that enhance antibiotic efficacy against resistance, often worsened by bacterial biofilms [

1,

10,

11,

12]. Virulence factors and biofilm formation are regulated by

S. aureus quorum sensing (QS), which is controlled by accessory global regulator (Agr) and staphylococcal accessory (Sar) proteins [

13,

14]. Identifying QS inhibitors could address these strategies as anti-virulence and anti-drug-resistant agents.

The Yucatan peninsula has high fungal endemicity, with unique fungi that are important for chemical-biological research and potential antimicrobial agents [

15].

Trametes villosa, found globally, including the Yucatan peninsula, is an endophytic fungus [

16,

17,

18] with annual basidiomata of flexible consistency measuring 7–49 × 10–22 × 2–3 mm. It has a flabellate pileus, colored beige to ivory at the margins and gray to ebony at the base, with greenish hues from the algae. The surface is villose with radial striations, and the margins are acute and lobed. The hymenophore has dark brown angular to hexagonal pores, 1–3 per mm [

19]. While the biological activity and chemical composition of

T. villosa remain unreported, other

Trametes species show activity against

S. aureus [

20,

21], as well as

Staphylococcus epidermidis,

Enterococcus raffinosus, and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

22]. In addition, the chemical composition of other

Trametes species has been reported, identifying compounds such as fatty acids, flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, saponins, steroids, triterpene cardiotonic glycosides, sterols, ribonucleotides, phenols, glycosides, and furans [

23,

24,

25].

This study evaluated three polarity fractions from a Yucatan peninsula T. villosa on S. aureus growth and its virulence and resistance mechanisms, examining the chemical compositions and molecular docking of Agr and Sar proteins.

2. Materials and Methods

This project was approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committees National of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), with approval number R-2025-785-066.

2.1. Extract Preparation

2.1.1. Collection

Trametes villosa basidiomata (

Figure 1) were collected in Anikabil Archeo-Botanical Park, Mérida Yucatán (20.988° N–89.686° W) and voucher specimens were deposited at UADY’s “Alfredo Barrera Marín” Herbarium., Mérida, Mexico [H.Maldonado04(UADY)]; species identification was performed by Dr. J.P. Pinzón.

2.1.2. Extract and Fractions Preparation

The collected basidiocarps of T. villosa were meticulously cleaned using a brush to eliminate any impurities. Subsequently, the samples were oven-dried at 40 °C for 72 h. The fungal material was then ground using a handheld mill. The crushed fungal material was extracted with absolute grade ethanol (Fermont, Monterrey, NL, Mexico) at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio through dynamic maceration in an orbital shaker (MAXQ-2000 model 431-A, Thermo Fisher ScientificInc, Waltham, MA, USA) at a speed of 0.106× g for 24 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the cartridge was decanted and filtered, and a fresh solvent was added. This process was repeated thrice. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (Büchi model R-215, Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland).

The ethanolic crude extract was fractionated using a liquid–liquid extraction method, as described by Can-Aké et al. (2024) [

26]. This was resuspended in a methanol/H

2O mixture (3:2, 250 mL) using a separatory funnel. The mixture was subsequently extracted with

n-hexane (

n-Hex, 500 mL, 3×) and ethyl acetate (EtOAc, 500 mL, 3×). Finally, the solvent from each fraction and hydroalcoholic residue was evaporated using a rotary evaporator, yielding three fractions: non-polar (

n-Hex), medium-polarity (EtOAc), and polar (methanol/H

2O residue).

The fractions were stored at −20 °C until they were employed for anti-staphylococcal assays and chemical analyses.

2.2. Antibacterial Activity

2.2.1. Bacterial Strains

The ATCC strains and clinical isolates of

S. aureus used in this study are part of the biobank of the Unidad de Investigación Médica Yucatán of IMSS. The characteristics of reference strains and clinical isolates are shown in

Table 1.

2.2.2. Anti-Growth Activity

The anti-growth activity of the fractions was determined using the Resazurin Microtiter Assay (REMA) [

27]. Briefly, 100 μL of a bacterial suspension [1:50 (

v/

v) of 0.5 McFarland] was added to 100 μL of MHC-containing fungal fractions in serial dilutions, resulting in a total volume of 200 μL, with fungal fraction concentrations ranging from 2000 to 15.7 μg/mL. All assays included positive control (cultures with wells containing a type-specific antimicrobial), negative control (growth), and sterility control (broth). Each microplate was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. After incubation, 30 μL of resazurin (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was added to each well of the microplate, and the wells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The blue-to-pink color change was interpreted as an indicator of bacterial growth. Anti-growth results were reported as MIC, which is the lowest concentration that completely prevents the visible growth of the strain. We also expressed the anti-growth activity in terms of the IC

50 by quantifying the cell viability by measuring the fluorescence of resorufin, a product of the metabolic reduction in the non-fluorescent resazurin dye by viable cells. Fluorescence was detected at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm using a microplate reader (Varioskan Lux, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Each assay was performed in triplicate.

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by taking five microliters from the microplate where the MIC was measured, at concentrations of 4×, 2×, 1×, and 1/2× MIC on Mueller Hinton agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The MBC was defined as the concentration at which no bacterial growth was observed. The MBC to MIC ratio was calculated to determine whether the active fractions were bacteriostatic or bactericidal. A ratio above four indicates bactericidal activity, whereas a ratio below four indicates bacteriostatic activity [

27].

2.2.3. Anti-Hemolysins Assay

The hemolysin production inhibition assay was performed as described by Uc-Cachón et al., 2024 [

27]. Briefly, bacterial strains were pretreated for 24 h with fractions at sub-inhibitory concentrations for bacterial growth (500–31.5 µg/mL). The supernatant was then recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm, and 100 rpm was mixed with 300 µL of erythrocyte suspension (300 µL of red blood cells + 5 mL of 0.9% saline). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for one hour with shaking at 200 rpm. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged for four minutes at 4000 rpm, and 100 µL of the supernatant was added to a microplate, and the optical density (OD) at 430 nm was determined using a microplate reader. For this assay, three replicates were performed with their respective duplicates, and the percentage of inhibition and the IC

50 of hemolysin production were calculated.

2.2.4. Anti-Biofilm Assay

To assess biofilm formation inhibition, crystal violet staining was employed [

27]. Briefly, an overnight culture was adjusted to a turbidity of 0.5 on the McFarland scale and then diluted 1:50 with tryptone-casein soy broth supplemented with 1% glucose (

w/

v; TCB+G). A 100 µL aliquot of this suspension was combined with 100 µL of TCB+G containing fractions in serial dilutions (500–125 µg/mL) in a 96-well microplate. Each assay included a positive control (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), a negative control (untreated bacteria), and a sterility control (culture broth). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the culture medium was removed, and the microplates were washed to eliminate any remaining planktonic cells from the wells. The biofilms were heat-fixed and stained with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA). Finally, the crystal violet was dissolved, and the density was measured at 490 nm. For this assay, three replicates with their respective duplicates were conducted, and the percentage inhibition and IC

50 values for biofilm formation were calculated.

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the fractions was evaluated against human keratinocyte cell line (HaCat, ATCC-12191) and African green monkey kidney epithelial cells (VERO, ATCC CCL-81) from the American Type Culture Collection (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA). They were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin (InVitro, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (InVitro, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B (InVitro, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in a 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere at 37 °C.

Cells undergoing exponential growth were seeded in a 96-well cell culture plate; 100 μL of cell suspension at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/mL was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. Twenty-four hours later, when the cells reached 80–90% confluence, the medium was replaced, and the cells were treated with different concentrations of fractions (31.25–500 µg/mL) in medium without FBS. At the end of 48 h of exposure, the medium was removed, and the cells were fixed by adding 50 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid solution to each well and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. After incubation, trichloroacetic acid was eliminated, and 50 μL of sulforhodamine B (0.1% sulforhodamine B in 1% acetic acid) was added to each well and left in contact with the cells for 30 min, after which they were washed with 150 μL of 1% acetic acid and rinsed three times until only the dye adhering to the cells remained. The plates were dried, and 100 μL of 10 mM Tris base was added to each well to solubilize the dye. The plates were shaken gently for 10 min, and cellular proliferation was determined by measuring the OD at 540 nm. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the 50% cytotoxicity concentrations (CC50) were determined.

2.4. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Fractions were analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) on a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 gas chromatograph coupled to an ISQ LT single-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an HP-5MS UI capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film). Ultra-high-purity helium (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. Samples (1 µL) were injected in the splitless mode (purge 50 mL min−1). The oven program was set to 50 °C for 1 min, ramped at 4 °C min−1 to 220 °C and held for 2 min, then 5 °C min−1 to 300 °C and held for 1 min. The inlet and transfer lines were maintained at 250 °C, respectively. Electron impact (EI, 70 eV) mass spectra were acquired in the full-scan mode (m/z 50–700). Compound identification was based on spectral comparison with the NIST MS library (MS Search v2.0), reporting similarity (SI) and reverse similarity (RSI) indices; matches with SI or RSI ≥ 700 were considered reliable. Lower-scoring signals were retained, when appropriate, as class-level annotations supported by diagnostic EI fragmentation and late retention on a 5%-phenyl/95%-PDMS stationary phase. The EtOAc fraction was derivatized before analysis. Specifically, 10 mg of the fraction was dissolved in pyridine (370 µL) and BSTFA (N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (50 µL), followed by incubation at 50 °C for 1 h.

2.5. Molecular Docking on Quorum-Sensing Receptors of S. aureus

Molecular docking was performed on the quorum-sensing receptors of

S. aureus, AgrA and SarA, as previously reported by Ganesh et al. (2022) [

28]. First, the X-ray crystal structures of

S. aureus AgrA (PDB ID: 4G4K, 1.52 Å) and SarA (PDB ID: 2FNP, 2.60 Å) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (

https://www.rcsb.org/, accessed on 31 October 2025). The receptor structures were prepared using UCSF Chimera version 1.19, in which all co-crystallized ligands, ions, and water molecules were removed to prevent steric interference during docking. Protein protonation was performed using the AMBER ff14SB (AMB-1) force field, and polar hydrogens were added to maintain proper geometry and hydrogen-bonding capacity.

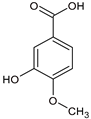

The three-dimensional structures of the selected ligands (benzoic acid, azelaic acid, and isovanillic acid) were obtained from the PubChem database (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 31 October 2025) and geometrically optimized to reach their lowest-energy conformations. Partial atomic charges were assigned using the Gasteiger–Marsili method to ensure consistency with the receptor electrostatic parameters.

Molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina 1.2.7, which defined a grid box encompassing the known or predicted active site of each receptor. The exhaustiveness parameter was set to 32 to enhance the conformational sampling and improve the accuracy of the predicted binding poses. The docking protocol assumed a rigid receptor and fully flexible ligands, allowing the exploration of all plausible orientations within the active site.

The docked poses were ranked based on binding affinity (kcal/mol), and the top-ranked conformations were further analyzed for hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, π–π interactions and van der Waals forces. Discovery Studio Visualizer (BIO-VIA) 4.5 and Chimera X 1.11 were employed to generate 2D and 3D interaction diagrams, highlighting the key residues involved in ligand recognition and stabilization within the binding pocket.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The values of IC50, CC50 and data analysis were conducted using R. software (v.4.3.2). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the inhibition percentage data. To identify statistically significant differences among the data, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. In all statistical analyses, results with p-values greater than 0.05 were considered non-significant.

4. Discussion

The increased prevalence of AMR has contributed to a significant increase in the incidence of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. These infections not only prolong hospital stays but also profoundly impact mortality rates, health outcomes, and healthcare costs. The variety of drug-resistant strains has expanded, with the emergence of “superbugs” such as MRSA, which complicates treatment due to the scarcity of effective therapeutic options [

29]. As a result, devising strategies to combat drug-resistant bacteria has become an urgent necessity.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report on the anti-

S. aureus activity of

T. villosa fungus. The

n-Hex and EtOAc fractions exhibited significant (31.25–2000 µg/mL) activity against both reference and clinical isolates of

S. aureus, including multidrug-resistant strains that exhibit resistance to methicillin and vancomycin. Notably, vancomycin is regarded as one of the final therapeutic options for the treatment of MRSA. Previous studies have documented the activities of other

Trametes species, such as

T. versicolor. Specifically, its MeOH extract exhibited bacteriostatic activity against clinical MRSA isolates at concentrations ranging from 3170 to 4250 µg/mL [

20]. Conversely, another study indicated that ethanolic (70%), chloroform, and hot water extracts of three

Trametes spp. were active against methicillin-sensitive (ATCC-25923) and MRSA (ATCC-33591) strains within the concentration range of 500–1170 µg/mL [

21]. All active fractions in our study exhibited bacteriostatic properties, except for the n-Hex fraction against SAU UIMY-1, which demonstrated bactericidal activity. While bactericidal activity is often considered the optimal approach for addressing bacterial infections, there remains a lack of consensus regarding its superiority over bacteriostatic activity. Some studies have documented that certain drugs with bacteriostatic properties are equally effective in treating lung, skin, and soft-tissue infections as those with bactericidal properties [

30,

31].

There is increasing interest in identifying compounds that can inhibit virulence factors and combat AMR. Numerous studies have highlighted the significant impact of virulence factors on the prognosis of patients. The expression of these factors is critical for the initiation and progression of infections [

32,

33]. Consequently, antivirulence drugs have emerged as viable alternatives to traditional antibiotics.

Staphylococcus aureus produces many virulence factors that contribute substantially to its success as a pathogen. These virulence factors can manipulate the host immune response and exacerbate tissue and organ damage, causing severe disease. Secreted bacterial toxins, such as α-toxin, are hemolysins secreted by 95% of pathogenic strains of

S. aureus. This toxin correspond to a monomer that oligomerizes to form a heptamer upon binding to host cells, subsequently inserting into the membrane to form pores that cause lysis of red blood cells and leukocytes [

34,

35]. In this context,

T. villosa fractions appear promising, exhibiting potent anti-virulence properties, specifically through the inhibition of hemolytic activity in reference strain and clinical

S. aureus isolates. Research on fungal extracts with anti-hemolytic properties is limited. A fraction of the MeOH crude extract from marine-derived

Aspergillus welwitschiae, processed through a Sephadex™ LH-20 column at a concentration of 100 µg/mL, demonstrated a 50% reduction in hemolytic activity of

S. aureus ATCC 29213. At a concentration of 400 µg/mL, the anti-hemolytic activity reached 80% in the MRSA clinical isolate IC 35777 [

36]. Our fractions exhibited greater potency than those in previous studies, with IC

50 values less than or equal to 53.8 ± 5.1 µg/mL.

In the pursuit of adjuvants to address AMR, there is an increasing interest in fractions or compounds that demonstrate efficacy against bacterial biofilms. Biofilms, which consist of bacterial cells encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix, are the primary factor contributing to treatment failure in

S. aureus infections. These biofilms create a favorable environment conducive to evading both antibiotics and the host immune system. Notably,

S. aureus within biofilms exhibits resistance to antibiotics at concentrations 10–1000 times higher than those required to inhibit planktonic

S. aureus. Furthermore, biofilms have been observed to facilitate the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes [

37,

38]. The fractions derived from

T. villosa demonstrated efficacy against biofilms formed by both reference strains and clinical isolates of

S. aureus. Remarkably, the EtOAc fraction exhibited superior activity compared to the positive control, EDTA, a chemical known to inhibit biofilm formation [

39]. Similar findings have been reported in studies involving other species of the

Trametes genus. Specifically, the chloroform extract of

T. elegans at a concentration of 250 µg/mL achieved a 69.75 ± 0.01% reduction in

S. aureus (ATCC25923) biofilm formation. At the same concentration the hot water extract achieved a 50 ± 0.02% reduction, while the 70% ethanol extract achieved a 41.18 ± 0.01% reduction. Comparable results were observed for the hot water and 70% ethanol extracts of

T. versicolor, which inhibited biofilm formation of

S. aureus ATCC 25923 by 41.18 ± 0.01% and 42.86 ± 0.01%, respectively, at a concentration of 250 µg/mL [

40].

The examination of the cytotoxic effects of fungal fractions is essential for assessing their potential risks and benefits. Evaluating the toxicity of these natural products is crucial, as it provides valuable insights into their safety and efficacy [

41]. In our study, we focused on the active fractions using kidney cell lines from the African green monkey (ATCC Vero CCL-18), which are particularly effective in determining the biocompatibility and safety of fractions or compounds derived from fungi or plants [

41]. Human keratinocytes (HaCat ATCC-12191) were used to evaluate safety in contexts related to human skin applications [

42]. The EtOAc fraction exhibited lower toxicity than the

n-Hex fraction, and both fractions demonstrated reduced toxicity towards skin cells. Both cell lines were susceptible to the concentrations necessary to kill most strains of

S. aureus, except for SAU UIMY-1, the SI for anti-growth activity may result in a very low value and indicates a relatively high toxicity. However, it is important to emphasize that a lower concentration was required to inhibit hemolysis and biofilm formation than to induce cell-death. The SI was determined by comparing the CC

50 and IC

50 values for hemolysis. It was found that a concentration 4.4 to 9.0 times higher than that required to inhibit 50% hemolysis is necessary to achieve 50% mortality in the kidney cell type. The selectivity index was notably higher in skin cells, with values ranging from 7.2 to 11.

Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant etiological agent of skin and soft tissue infections. In the United States, these infections result in over 10 million outpatient consultations and approximately 500,000 hospital admissions annually [

43]. This bacterium secretes various virulence factors, including several membrane-damaging toxins that can form pores in the cytoplasmic membranes of host cells, such as human keratinocytes, epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and erythrocytes. Pore formation leads to cell lysis, complicating the infection and delaying the healing process. Notably, the inhibition of these virulence factors has been associated with a reduction in lesion size and dermonecrosis in a skin infection model [

43]. Consequently, our fractions present a promising avenue for developing alternative treatments for skin infections caused by this pathogen.

Analysis of the chemical composition of the active fractions of

T. villosa revealed that the

n-Hex fraction predominantly comprises alkane-type compounds, aldehydes, and fatty acids. The effectiveness of fatty acids against

S. aureus is well-documented, with research showing their capacity to prevent biofilm formation and provide additional anti-infective effects by suppressing the expression of key

S. aureus virulence factors critical to the pathogenesis of the disease, including hemolysins. These fatty acids are considered promising candidates for anti-staphylococcal treatment [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Moreover, the compounds 1-methylene-2-benzoyl-6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline, [2,2′-Binaphthalene]-1,4,5′,8′-tetrone,1′,8-dihydroxy-3,6′-dimethyl and 9,10-Anthracenedione, 2-[4-(acetyloxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]-1,3,6,8-tetramethoxy may also play a role in the anti-

S. aureus activity in the

n-Hex fraction. These natural derivatives of alkaloids, naphthoquinones and anthraquinones are known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties [

49,

50,

51]. The EtOAc fraction contains interesting compounds in addition to sugars and fatty acids. Among these is benzoic acid, which has been found in

T. versicolor from Japan [

52]. It displayed activity against

S. aureus with an MIC value of 587 µg/mL [

53]. This compound affects the bacterial cell wall and internal membrane, disrupting metabolism and enzymes. Additionally, it can alter the lipid profile, inhibit enzymes such as ATPase, block cell division, prevent biofilm formation, and change bacterial shape. This results in the formation of membrane channels that lead to the leakage of essential ions, ATP, and nucleic acids, ultimately causing cell death [

53,

54]. Isovanillic acid was identified as a constituent of

T. suaveolens collected in Vietnam [

55]. A study conducted in mice demonstrated the protective potential of this compound against

S. aureus, specifically highlighting its ability to inhibit the virulence factors associated with coagulation [

56]. Although azelaic acid has not been reported in

Trametes species, it has been identified in other basidiomycetes. This compound is currently used in cosmeceuticals because of its antibacterial properties [

57]. It has demonstrated efficacy against

S. epidermidis and

Propionibacterium acnes, with its mechanism of action attributed to its involvement in the membrane proton gradient of both bacteria [

58]. Additionally, this compound exhibited activity against an MRSA strain, with an IC

50 value of 850 µg/mL [

59].

In our study, we performed a docking molecular analysis of—benzoic, isovanillic, and azelaic acids—on the proteins AgrA and SarA. AgrA serves as the central transcriptional activator of QS, which is crucial for biofilm and virulence factor production, whereas SarA is a global regulator that stabilizes biofilms and enhances virulence factor production [

60]. Notably, all three molecules demonstrated significant binding affinities to both proteins, potentially explaining the inhibition of hemolysins and biofilms in the EtOAc fraction. Isovanillic acid exhibited the highest binding affinity for both receptors, followed by benzoic acid. Notably, isovanillic acid is a substituted benzoic acid that features a hydroxyl group and a methoxy group attached to the benzene ring. Our findings suggest that these groups enhance binding to AgrA and SarA proteins. Previously, other benzoic acid derivatives, such as 3-hydroxybenzoic acid, have shown binding affinities to AgrA and SarA with lower binding energies of −4.4 kcal/mol and −4.1 kcal/mol, respectively. In the same study, this compound inhibited 90.34% of biofilm formation and the zone of hemolysis by

S. aureus SA-01 at a concentration of 25 μg/mL [

28].

Collectively, these findings suggest that the bioactivity of T. villosa fractions results from a synergistic interplay between fatty acids, phenolic acids, and quinone derivatives. These compounds may act on multiple bacterial targets—disrupting membranes, modulating virulent gene expression, and impairing energy metabolism, thereby contributing to the observed anti-S. aureus effects.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to document the pharmacological activity and chemical composition of T. villosa collected from the Yucatan peninsula.