Beyond the Spike Glycoprotein: Mutational Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, RNA Extraction, and Quantification

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

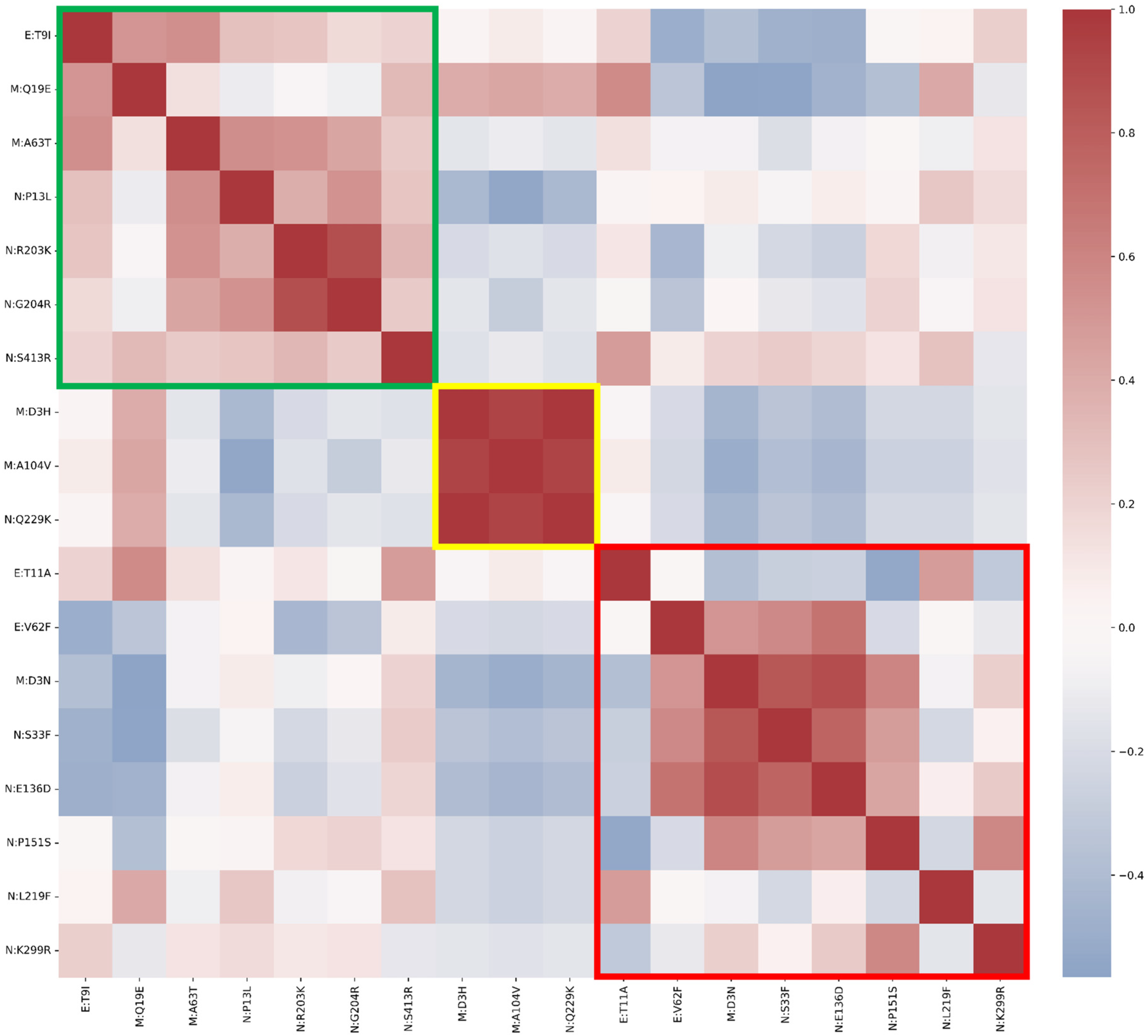

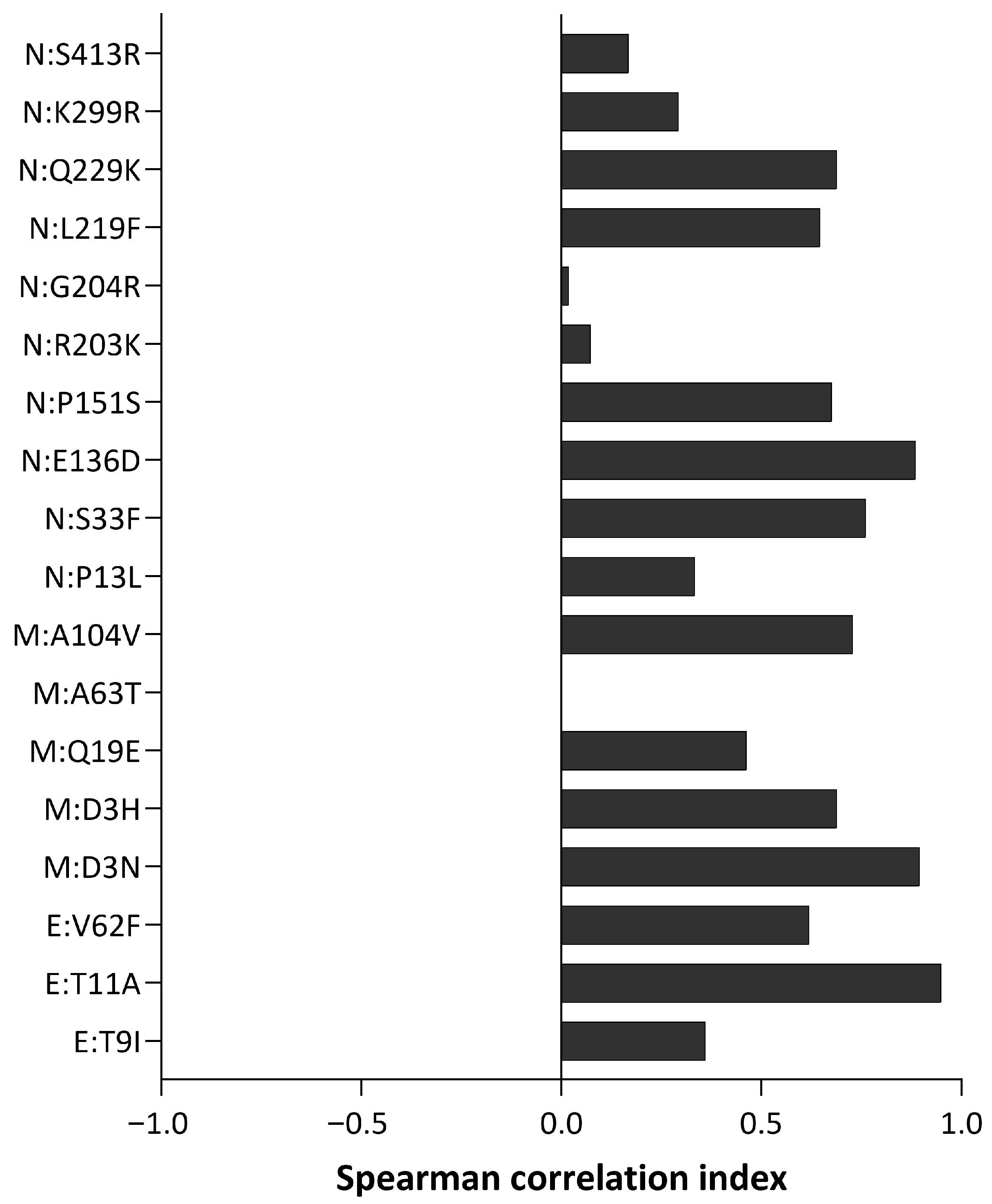

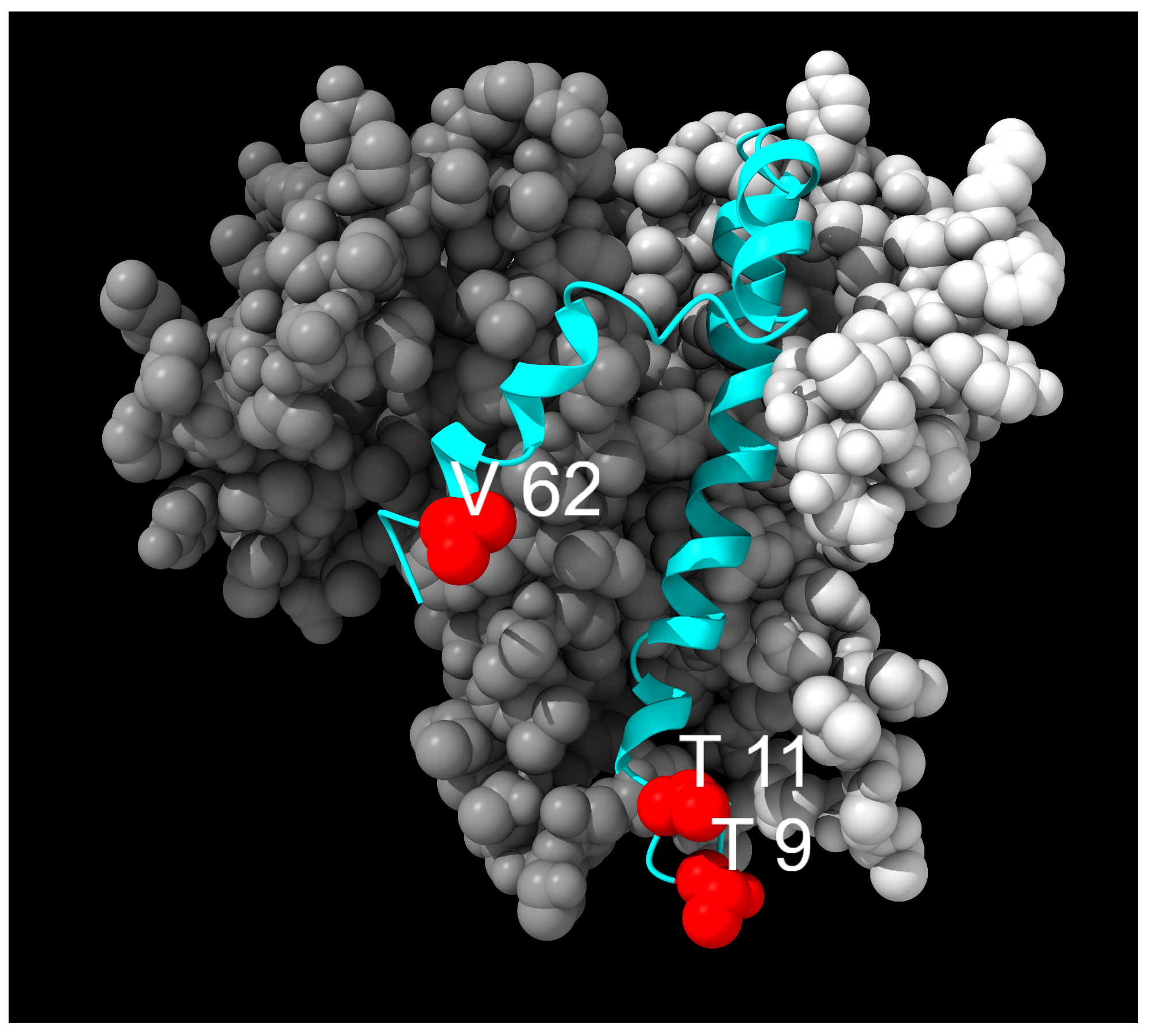

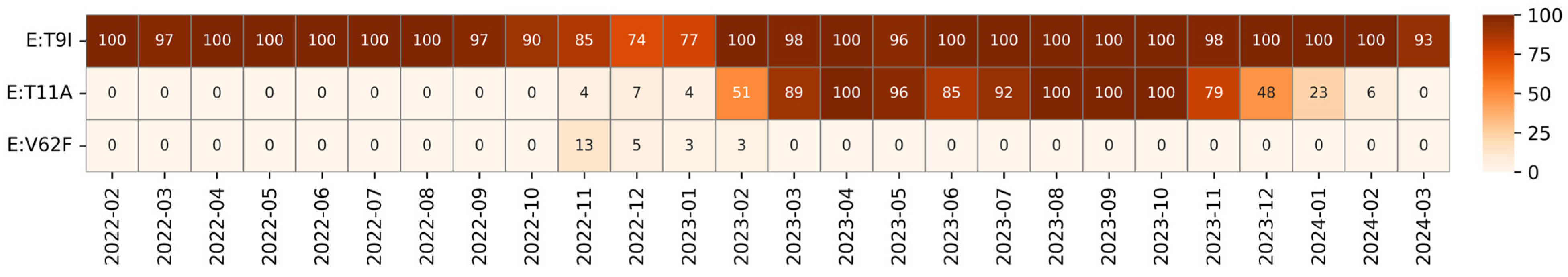

3.1. Envelope Mutations

3.2. Membrane Protein Mutations

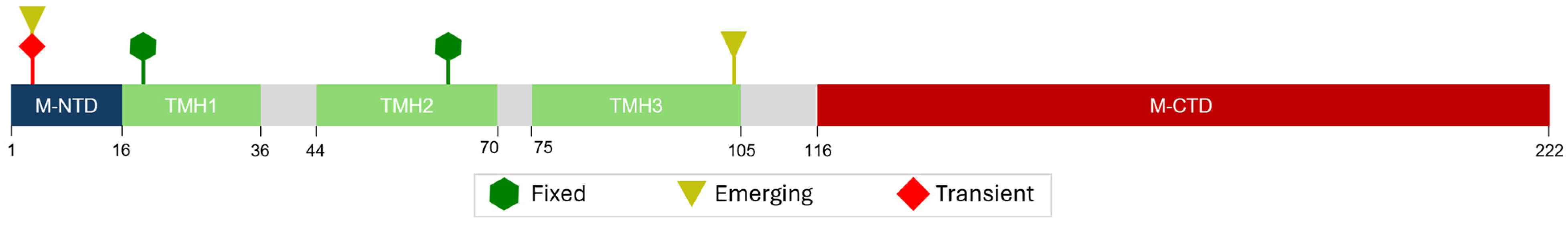

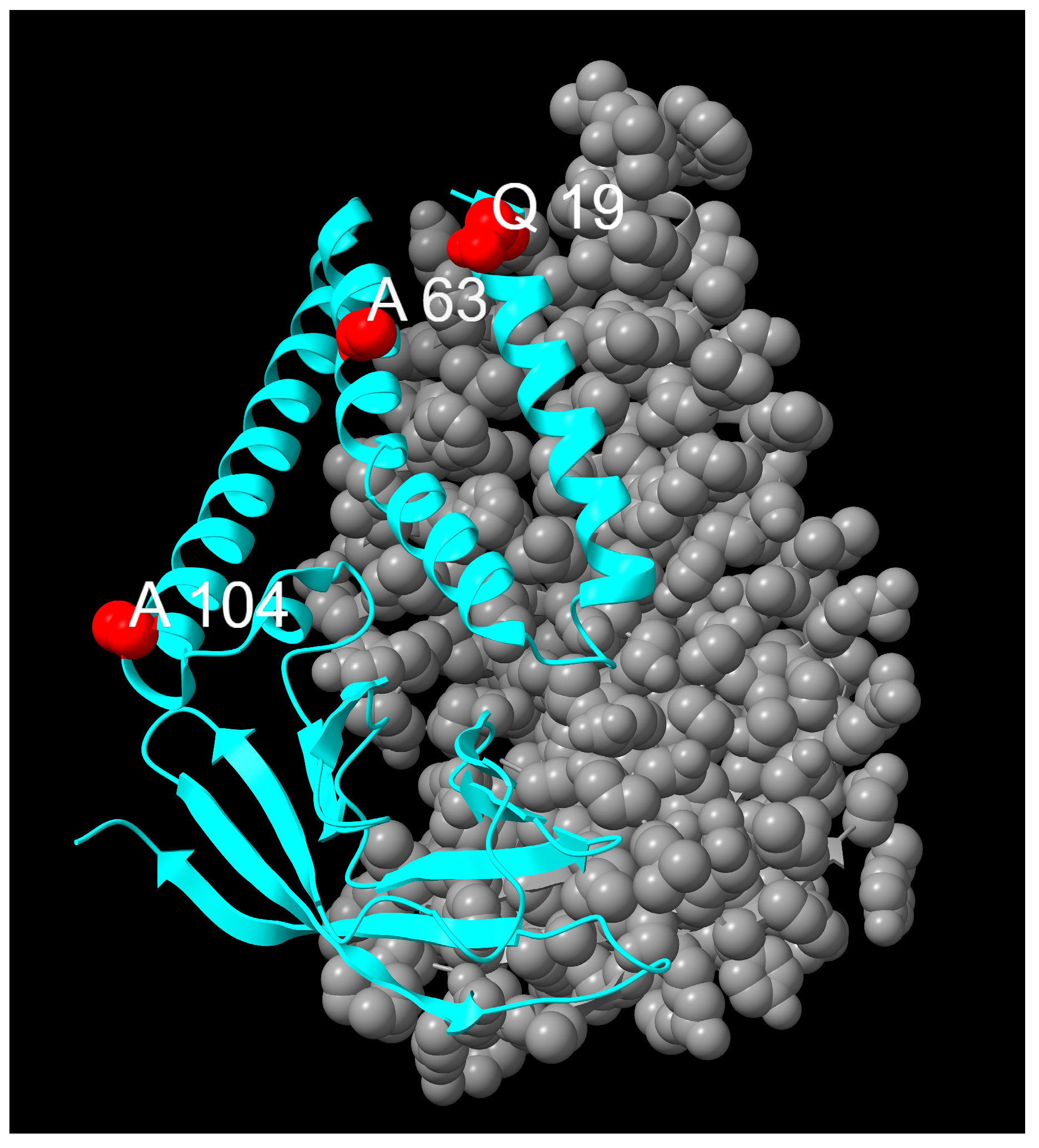

3.3. Nucleocapsid Mutations

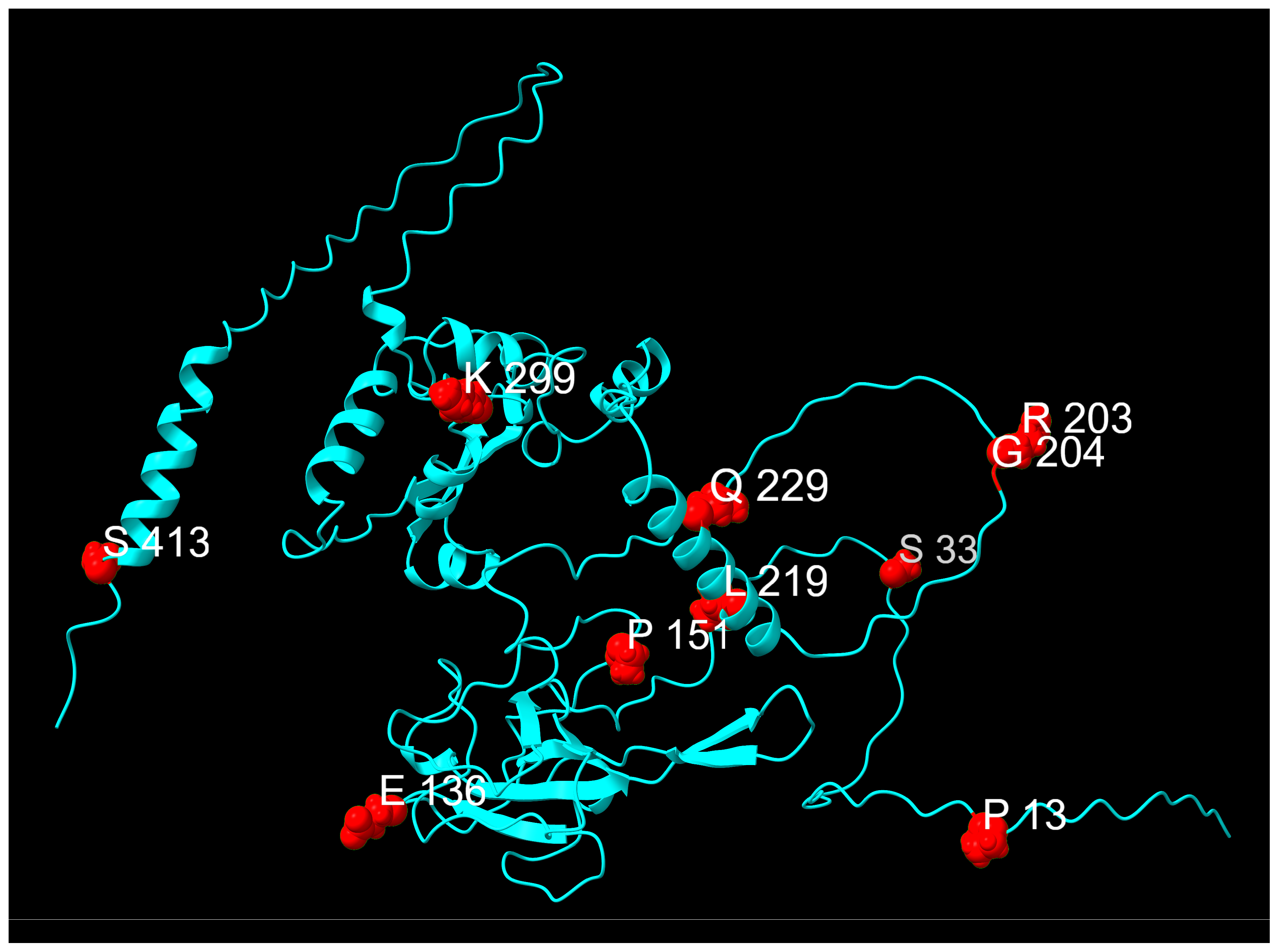

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOUI | Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata |

| CTD | C-terminal Domain |

| E | Envelope |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| GISAID | Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data |

| IDR | Intrinsically Disordered Region |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IGV | Integrative Genomics Viewer |

| ISS | Istituto Superiore di Sanità |

| LKR | Linker Region |

| M | Membrane |

| N | Nucleocapsid |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NSP | Non-structural protein |

| NTD | N-terminal Domain |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| S | Spike |

| SARS-CoV | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus |

| TMD | Transmembrane Domain |

| TMH | Transmembrane Helix |

| UOC | Unità Operativa Complessa |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A New Coronavirus Associated with Human Respiratory Disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.; Kratzel, A.; Barut, G.T.; Lang, R.M.; Aguiar Moreira, E.; Thomann, L.; Kelly, J.N.; Thiel, V. SARS-CoV-2 Biology and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; O’Toole, Á.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Ruis, C.; du Plessis, L.; Pybus, O.G. A Dynamic Nomenclature Proposal for SARS-CoV-2 Lineages to Assist Genomic Epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, P.; Kempf, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Schulz, S.R.; Jäck, H.M.; Pöhlmann, S.; Hoffmann, M. Omicron Sublineage BQ.1.1 Resistance to Monoclonal Antibodies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetto, R.; Tonon, E.; Palmisano, A.; Lagni, A.; Diani, E.; Lotti, V.; Mantoan, M.; Montesarchio, L.; Palladini, F.; Turri, G.; et al. An Italian Single-Center Genomic Surveillance Study: Two-Year Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Mutations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, R.; Lee, I.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Meng, X. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 E Protein: Sequence, Structure, Viroporin, and Inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Martin, M.-J.; Orchard, S.; Magrane, M.; Ahmad, S.; Alpi, E.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Britto, R.; Bye-A-Jee, H.; Cukura, A.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, V.S.; McKay, M.J.; Shcherbakov, A.A.; Dregni, A.J.; Kolocouris, A.; Hong, M. Structure and Drug Binding of the SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Transmembrane Domain in Lipid Bilayers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilocca, B.; Soggiu, A.; Sanguinetti, M.; Babini, G.; De Maio, F.; Britti, D.; Zecconi, A.; Bonizzi, L.; Urbani, A.; Roncada, P. Immunoinformatic Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein as a Strategy to Assess Cross-Protection against COVID-19. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, H.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Ye, C.; Lin, W.; Hu, J.; Ji, J.; et al. The E Protein Is a Multifunctional Membrane Protein of SARS-CoV. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2003, 1, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S. The Structure of the Membrane Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Resembles the Sugar Transporter SemiSWEET. Pathog. Immun. 2020, 5, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Nomura, N.; Muramoto, Y.; Ekimoto, T.; Uemura, T.; Liu, K.; Yui, M.; Kono, N.; Aoki, J.; Ikeguchi, M.; et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Membrane Protein Essential for Virus Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorkhali, R.; Koirala, P.; Rijal, S.; Mainali, A.; Baral, A.; Bhattarai, H.K. Structure and Function of Major SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV Proteins. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2021, 15, 117793222110258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, K.A.; Dutta, M.; Kern, D.M.; Kotecha, A.; Voth, G.A.; Brohawn, S.G. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 M Protein in Lipid Nanodiscs. eLife 2022, 11, e81702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, D.C.; Chalupska, D.; Silhan, J.; Koutna, E.; Nencka, R.; Veverka, V.; Boura, E. Structural Basis of RNA Recognition by the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Phosphoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecky-Bromberg, S.A.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Frieman, M.; Baric, R.A.; Palese, P. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Open Reading Frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and Nucleocapsid Proteins Function as Interferon Antagonists. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Chen, C.-M.; Chiang, M.; Hsu, Y.; Huang, T. Transient Oligomerization of the SARS-CoV N Protein—Implication for Virus Ribonucleoprotein Packaging. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Akter, S.; Rashid, A.A.; Khair, S.; Alam, A.S.M.R.U. Unique Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants’ Non-Spike Proteins: Potential Impacts on Viral Pathogenesis and Host Immune Evasion. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 170, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diani, E.; Silvagni, D.; Lotti, V.; Lagni, A.; Baggio, L.; Medaina, N.; Biban, P.; Gibellini, D. Evaluation of Saliva and Nasopharyngeal Swab Sampling for Genomic Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Children Accessing a Pediatric Emergency Department during the Second Pandemic Wave. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1163438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, J.K.; Marshall, J.; Danecek, P.; Li, H.; Ohan, V.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; Davies, R.M. HTSlib: C Library for Reading/Writing High-Throughput Sequencing Data. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, Á.; Scher, E.; Underwood, A.; Jackson, B.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Colquhoun, R.; Ruis, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Taylor, B.; et al. Assignment of Epidemiological Lineages in an Emerging Pandemic Using the Pangolin Tool. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: Real-Time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Shu, Y.; McCauley, J. GISAID: Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data—From Vision to Reality. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure Visualization for Researchers, Educators, and Developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance for Representative and Targeted Genomic SARS-CoV-2; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021.

- Chen, C.; Nadeau, S.; Yared, M.; Voinov, P.; Xie, N.; Roemer, C.; Stadler, T. CoV-Spectrum: Analysis of Globally Shared SARS-CoV-2 Data to Identify and Characterize New Variants. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 1735–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, K.; Abdalla, M.; Wei, D.Q.; Khan, M.T.; Lodhi, M.S.; Darwish, D.B.; Sharaf, M.; Tu, X. Emerging Mutations in Envelope Protein of SARS-CoV-2 and Their Effect on Thermodynamic Properties. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 25, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, S.; Nchioua, R.; Cordsmeier, A.; Vishwakarma, J.; Koepke, L.; Alshammary, H.; Jung, C.; Hirschenberger, M.; Hoenigsperger, H.; Fischer, J.-R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Envelope T9I Adaptation 1 Confers Resistance to Autophagy 2 Running Title: E T9I Confers SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Autophagy Resistance. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Ji, H.; Zuo, X.; Xiao, G.-F.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.-K.; Xia, B.; Gao, Z. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Mutations on the Pathogenicity of Omicron XBB. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.; Shen, X.; He, Y.; Pan, X.; Liu, F.-L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Fang, S.; Wu, Y.; Duan, Z.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Causes Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)-like Pathological Damages and Constitutes an Antiviral Target. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchetto, R.; Tonon, E.; Medaina, N.; Turri, G.; Diani, E.; Piccaluga, P.P.; Salomoni, A.; Conti, M.; Tacconelli, E.; Lagni, A.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Δ426 ORF8 Deletion Mutant Cluster in NGS Screening. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Panasiuk, N.; Rabalski, L.; Gromowski, T.; Nowicki, G.; Kowalski, M.; Wydmanski, W.; Szulc, P.; Kosinski, M.; Gackowska, K.; Drweska-Matelska, N.; et al. Expansion of a SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant with an 872 Nt Deletion Encompassing ORF7a, ORF7b and ORF8, Poland, July to August 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hoque, M.N.; Islam, M.R.; Islam, I.; Mishu, I.D.; Rahaman, M.M.; Sultana, M.; Hossain, M.A. Mutational Insights into the Envelope Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2021, 22, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, Y.; Rost, B. Correlating Protein Function and Stability through the Analysis of Single Amino Acid Substitutions. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Pereira, C.; Pires, M.N.; Gouveia, R.P.; Pereira, N.N.; Caniceiro, A.B.; Rosário-Ferreira, N.; Moreira, I.S. SARS-CoV-2 Membrane Protein: From Genomic Data to Structural New Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, M.H.; Mahmanzar, M.; Rahimian, K.; Mahdavi, B.; Tokhanbigli, S.; Moradi, B.; Sisakht, M.M.; Deng, Y. Global Landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Conserved Regions. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhmola, S.; Indari, O.; Kashyap, D.; Varshney, N.; Das, A.; Manivannan, E.; Jha, H.C. Mutational Analysis of Structural Proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer-Stroh, S.; Eisenhaber, F. Myristoylation of Viral and Bacterial Proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H. Protein Myristoylation in Protein–Lipid and Protein–Protein Interactions. Biophys. Chem. 1999, 82, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.H.; Heal, W.P.; Mann, D.J.; Tate, E.W. Protein Myristoylation in Health and Disease. J. Chem. Biol. 2010, 3, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.K. Higher Omicron JN.1 Coronavirus Transmission Due to Unique 17MPLF Spike Insertion Compensating 24LPP, 69HV, 145Y, 211N and 483V. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Ren, L.; Wang, J. Functional Mutations of SARS-CoV-2: Implications to Viral Transmission, Pathogenicity and Immune Escape. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulas, A.; Zanti, M.; Tomazou, M.; Zachariou, M.; Minadakis, G.; Bourdakou, M.M.; Pavlidis, P.; Spyrou, G.M. Generalized Linear Models Provide a Measure of Virulence for Specific Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Strains. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0238665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradyan, N.; Arakelov, V.; Sargsyan, A.; Paronyan, A.; Arakelov, G.; Nazaryan, K. Impact of Mutations on the Stability of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Structure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.A.; Zhou, Y.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Vu, M.N.; Bopp, N.; Crocquet-Valdes, P.A.; Kalveram, B.; Schindewolf, C.; Liu, Y.; Scharton, D.; et al. Nucleocapsid Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Augment Replication and Pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.I.; Nazli, A.; Al-furas, H.; Asad, M.I.; Ajmal, I.; Khan, D.; Shah, J.; Farooq, M.A.; Jiang, W. An Overview of Viral Mutagenesis and the Impact on Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1034444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xing, N.; Meng, K.; Fu, B.; Xue, W.; Dong, P.; Tang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, G.; Luo, H.; et al. Nucleocapsid Mutations R203K/G204R Increase the Infectivity, Fitness, and Virulence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1788–1801.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; He, S.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, S.; Kang, S. Structural Insight Into the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein C-Terminal Domain Reveals a Novel Recognition Mechanism for Viral Transcriptional Regulatory Sequences. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 624765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Yamayoshi, S.; Halfmann, P.J.; Wilson, N.; Bobholz, M.; Vuyk, W.C.; Wei, W.; Ries, H.; O’Connor, D.H.; Friedrich, T.C.; et al. Sensitivity of Rapid Antigen Tests for Omicron Subvariants of SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nguyen, A.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Hassan, S.A.; Chen, J.; Shroff, H.; Piszczek, G.; Schuck, P. Plasticity in Structure and Assembly of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamotharan, K.; Korn, S.M.; Wacker, A.; Becker, M.A.; Günther, S.; Schwalbe, H.; Schlundt, A. A Core Network in the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid NTD Mediates Structural Integrity and Selective RNA-Binding. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussow, A.B.; Auslander, N.; Faure, G.; Wolf, Y.I.; Zhang, F.; Koonin, E.V. Genomic Determinants of Pathogenicity in SARS-CoV-2 and Other Human Coronaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 15193–15199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poran, A.; Harjanto, D.; Malloy, M.; Arieta, C.M.; Rothenberg, D.A.; Lenkala, D.; van Buuren, M.M.; Addona, T.A.; Rooney, M.S.; Srinivasan, L.; et al. Sequence-Based Prediction of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Targets Using a Mass Spectrometry-Based Bioinformatics Predictor Identifies Immunogenic T Cell Epitopes. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonon, E.; Cecchetto, R.; Diani, E.; Medaina, N.; Turri, G.; Lagni, A.; Lotti, V.; Gibellini, D. Surfing the Waves of SARS-CoV-2: Analysis of Viral Genome Variants Using an NGS Survey in Verona, Italy. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, M.G.L.; Spiteri, G.; Caliskan, G.; Lotti, V.; Carta, A.; Gibellini, D.; Verlato, G.; Porru, S. SARS-CoV-2 and Its Variants in Thrice-Infected Health Workers: A Case Series from an Italian University Hospital. Viruses 2022, 14, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccaluga, P.P.; Di Guardo, A.; Lagni, A.; Lotti, V.; Diani, E.; Navari, M.; Gibellini, D. COVID-19 Vaccine: Between Myth and Truth. Vaccines 2022, 10, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| E Mutations | Wild Type Polarity | Mutated Polarity | Domain | Involvement | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T9I | Polar | Hydrophobic | TMD | Autophagy resistance [35] | Fixed |

| T11A | Polar | Hydrophobic | TMD | Reduced pathogenicity [36] | Transient |

| V62F | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | E-CTD | Unknown | Transient |

| M Mutation | Wild Type Polarity | Mutated Polarity | Domain | Involvement | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3N | Negative | Polar | M-NTD | Protein interaction modulation [44] | Transient |

| D3H | Negative | Positive | M-NTD | Protein interaction modulation [44] | Emerging |

| Q19E | Polar | Negative | TMH1 | Protein stabilization [42] | Fixed |

| A63T | Hydrophobic | Polar | TMH2 | Protein stabilization [42] | Fixed |

| A104V | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | TMH3 | Unknown | Emerging |

| N Mutation | Wild Type Polarity | Mutated Polarity | Domain | Involvement | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P13L | Proline | Hydrophobic | N-arm | Protein stabilization [52] | Fixed |

| S33F | Polar | Hydrophobic | N-arm | Unknown | Transient |

| E136D | Negative | Negative | N-NTD | Unknown | Transient |

| P151S | Proline | Polar | N-NTD | Immune evasion [59] | Transient |

| R203K | Positive | Positive | LKR | Increased pathogenicity [53] | Fixed |

| G204R | Glycine | Positive | LKR | Increased pathogenicity [53] | Fixed |

| L219F | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | LKR | Enhanced protein stability [58] | Transient |

| Q229K | Polar | Positive | LKR | Unknown | Emerging |

| K299R | Positive | Positive | N-CTD | Unknown | Transient |

| S413R | Polar | Positive | C-tail | Protein stabilization [52] | Fixed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tonon, E.; Cecchetto, R.; Lotti, V.; Lagni, A.; Diani, E.; Palmisano, A.; Mantoan, M.; Montesarchio, L.; Palladini, F.; Turri, G.; et al. Beyond the Spike Glycoprotein: Mutational Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060150

Tonon E, Cecchetto R, Lotti V, Lagni A, Diani E, Palmisano A, Mantoan M, Montesarchio L, Palladini F, Turri G, et al. Beyond the Spike Glycoprotein: Mutational Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins. Infectious Disease Reports. 2025; 17(6):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060150

Chicago/Turabian StyleTonon, Emil, Riccardo Cecchetto, Virginia Lotti, Anna Lagni, Erica Diani, Asia Palmisano, Marco Mantoan, Livio Montesarchio, Francesca Palladini, Giona Turri, and et al. 2025. "Beyond the Spike Glycoprotein: Mutational Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins" Infectious Disease Reports 17, no. 6: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060150

APA StyleTonon, E., Cecchetto, R., Lotti, V., Lagni, A., Diani, E., Palmisano, A., Mantoan, M., Montesarchio, L., Palladini, F., Turri, G., & Gibellini, D. (2025). Beyond the Spike Glycoprotein: Mutational Signatures in SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins. Infectious Disease Reports, 17(6), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060150