Impact of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health Among Employees in Health and Social Services—A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

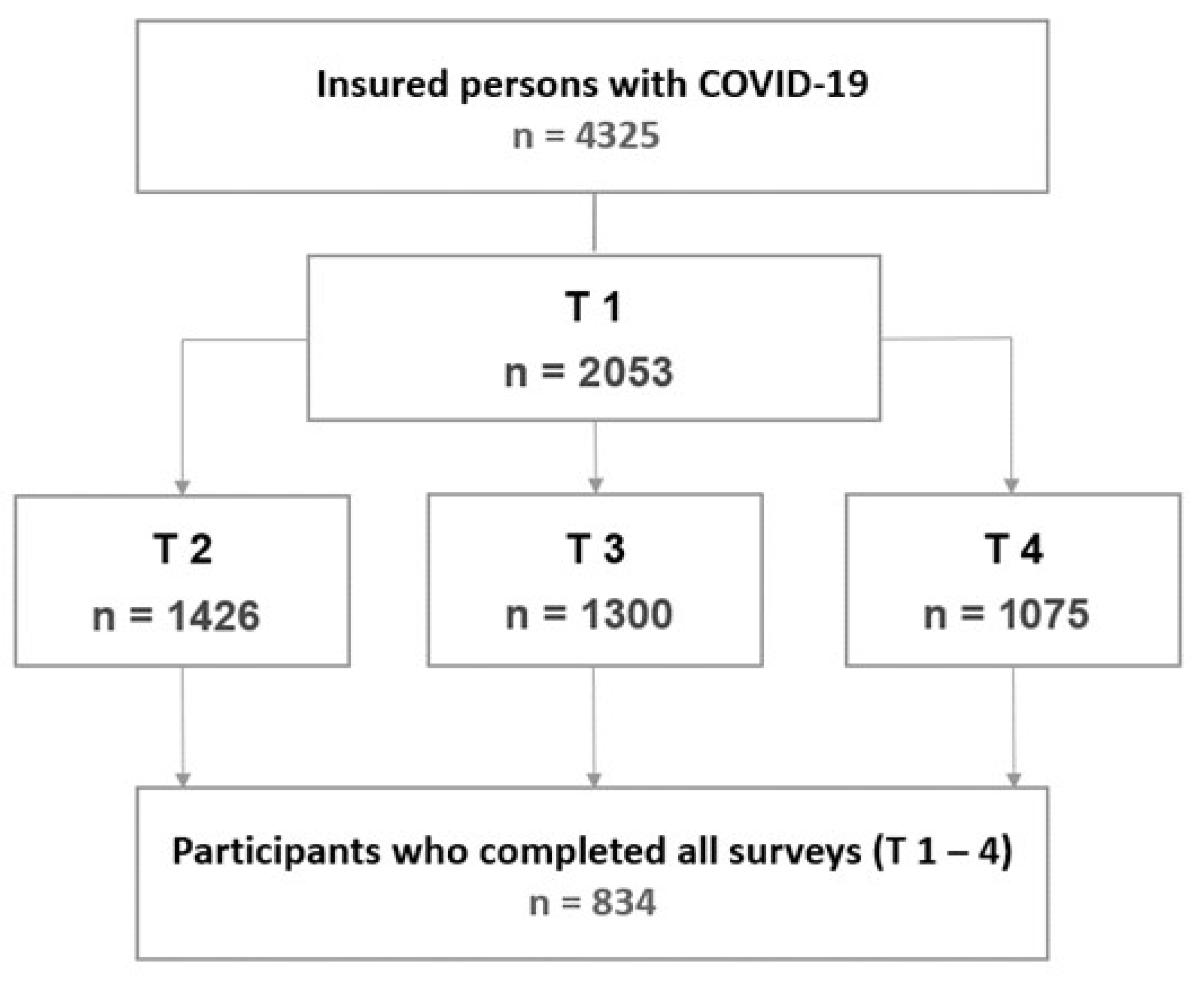

2.1. Study Description

2.2. Variables and Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

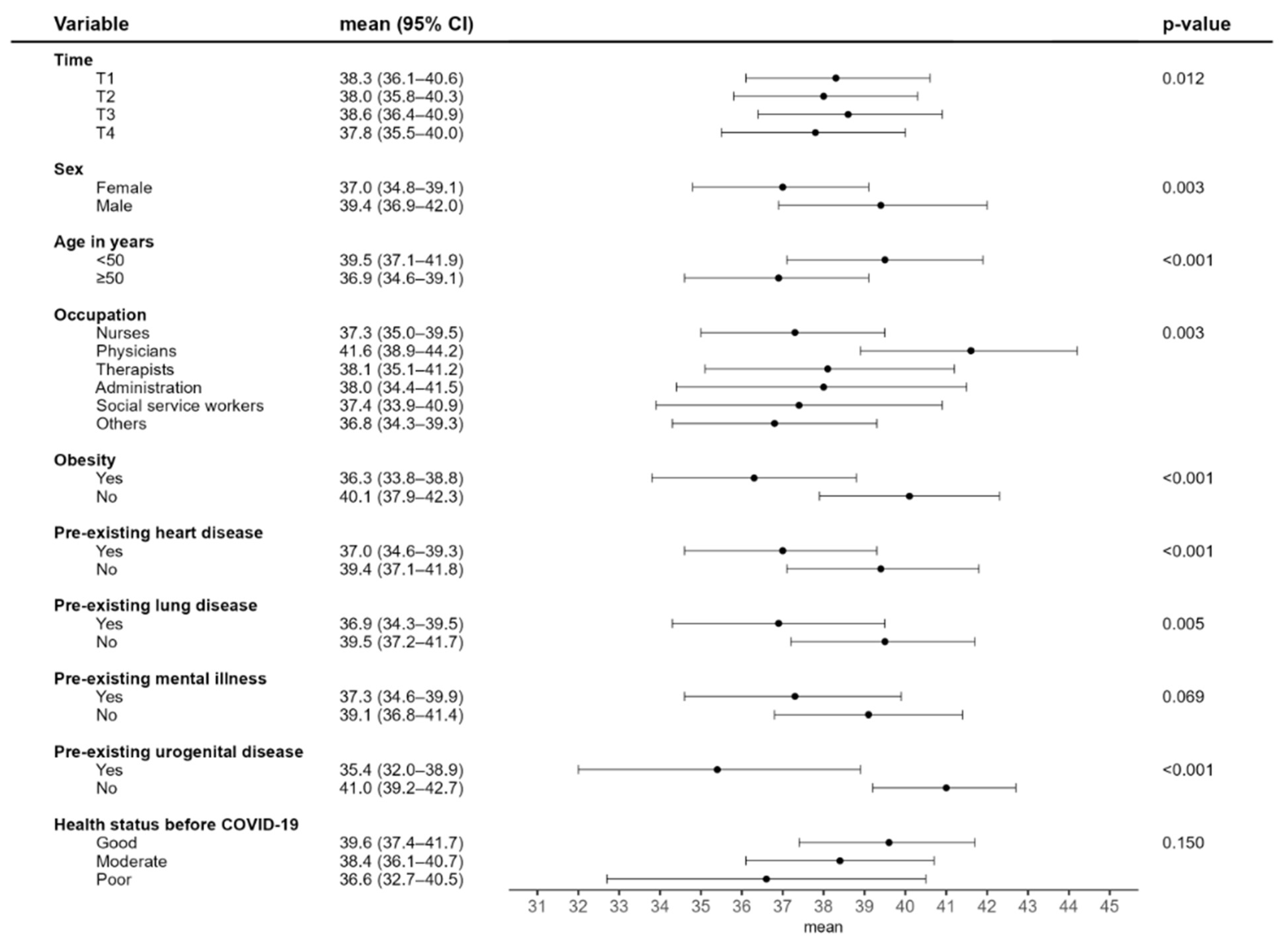

3.1. Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) and Contributing Factors

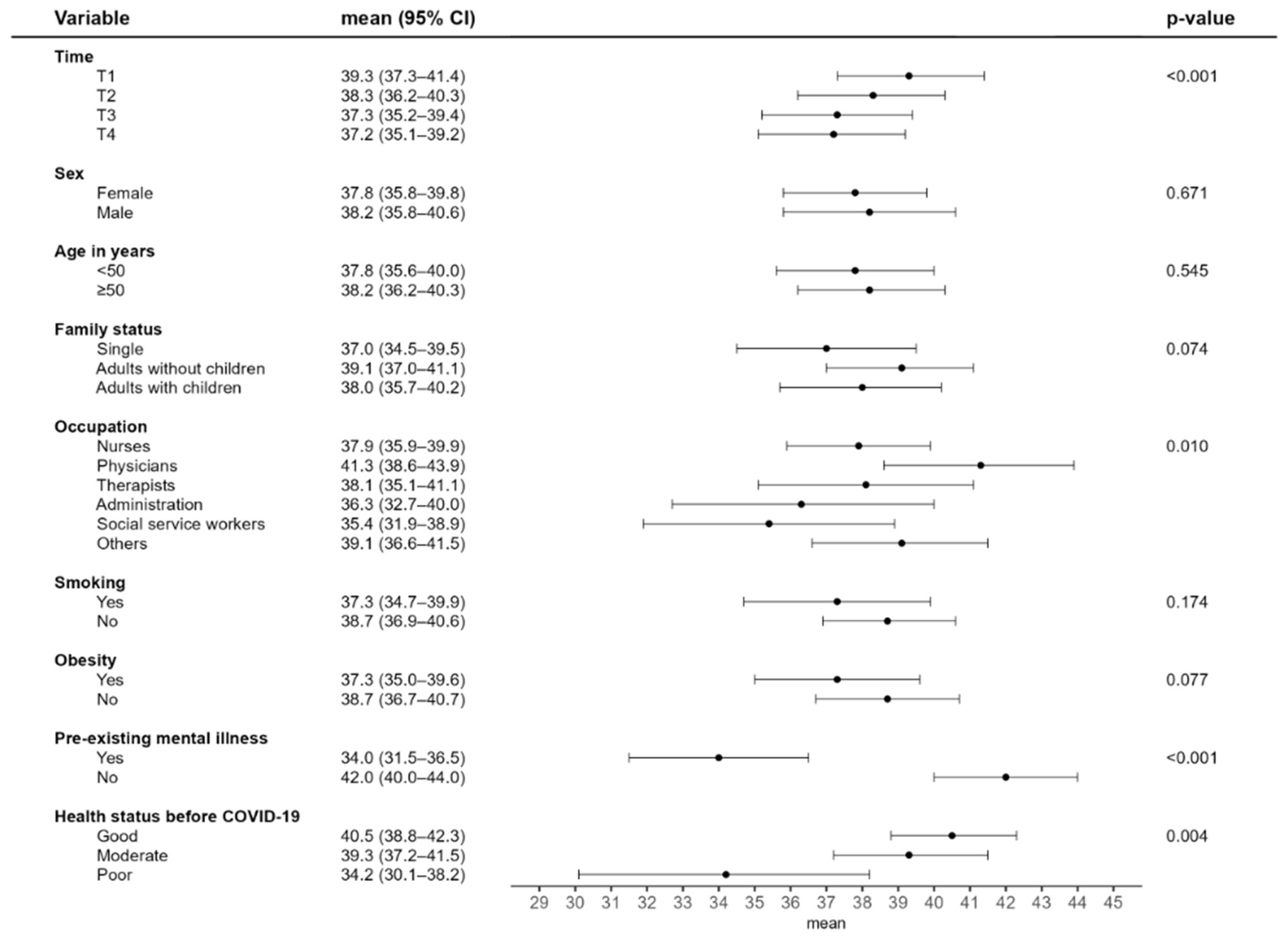

3.2. Development and Contributing Factors in Mental Health for Depression and Anxiety

4. Discussion

4.1. Health-Related Quality of Life

4.2. Predictors of HRQoL

4.3. Mental Health

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wachtler, B.; Neuhauser, H.; Haller, S.; Grabka, M.; Zinn, S.; Schaade, L.; Hövener, C.; Hoebel, J. The risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 among healthcare workers during the pandemic—Findings of a nationwide sero-epidemiological study in Germany. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 842–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; Rigó, M.; Formazin, M.; Liebers, F.; Latza, U.; Castell, S.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Greiser, K.H.; Michels, K.B.; Krause, G.; et al. Occupation and SARS-CoV-2 infection risk among 108 960 workers during the first pandemic wave in Germany. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2022, 48, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahrendorf, M.; Schaps, V.; Reuter, M.; Hoebel, J.; Wachtler, B.; Jacob, J.; Alibone, M.; Dragano, N. Occupational differences of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in Germany. An analysis of health insurance data from 3.17 million insured persons. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2023, 66, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, J.; Cajander, S.; Lidén, M.; Löfstedt, H.; Westberg, H. COVID-19 Across Professions—Infection, Hospitalization, and Intensive Care Unit Patterns in a Swedish County. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulon, M.; Stranzinger, J.; Wendeler, D.; Nienhaus, A. Occupational infectious diseases in healthcare workers 2023. Claims data from the Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health andWelfare Services. Zbl. Arbeitsmed. 2025, 75, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cajas, J.L.; Jolly, A.; Gong, Y.; Evans, G.; Perez-Patrigeon, S.; Stoner, B.; Guan, T.H.; Alvarado, B. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection before and after the Omicron wave in a cohort of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, R.S.; Eble, L.; Nieters, A.; Brockmann, S.O.; Göpel, S.; Merle, U.; Steinacker, J.M.; Kräusslich, H.G.; Rothenbacher, D.; Kern, W.V. Symptom Burden and Post-COVID-19 Syndrome 24 Months Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Longitudinal Population-Based Study. J. Infect. 2025, 90, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 NICE Guideline [NG188]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Mauz, E.; Walther, L.; Junker, S.; Kersjes, C.; Damerow, S.; Eicher, S.; Hölling, H.; Müters, S.; Peitz, D.; Schnitzer, S.; et al. Time trends in mental health indicators in Germany’s adult population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1065938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, Z.T.; Sun, X.C.; Chen, T.T.; Wu, X.T. Mental health status and related factors influencing healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0289454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niecke, A.; Henning, M.; Hellmich, M.; Erim, Y.; Morawa, E.; Beschoner, P.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Geiser, F.; Baranowski, A.M.; Weidner, K.; et al. Mental distress of intensive care staff in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from the VOICE study. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed. 2024, 120, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebeka, S.; Carcaillon-Bentata, L.; Decio, V.; Alleaume, C.; Beltzer, N.; Gallay, A.; Lemogne, C.; Pignon, B.; Makovski, T.T.; Coste, J. Complex association between post-COVID-19 condition and anxiety and depression symptoms. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchberger, I.; Meisinger, C.; Warm, T.D.; Hyhlik-Dürr, A.; Linseisen, J.; Goßlau, Y. Longitudinal course and predictors of health-related quality of life, mental health, and fatigue, in non-hospitalized individuals with or without post COVID-19 syndrome. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, L.; Buwalda, T.; Blair, M.; Forde, B.; Lunjani, N.; Ambikan, A.; Neogi, U.; Barrett, P.; Geary, E.; O’Connor, N.; et al. Impact of Long COVID on health and quality of life. HRB Open Res. 2022, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.; Dulon, M.; Westermann, C.; Kozak, A.; Nienhaus, A. Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Workers in Health and Social Services in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brähler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, I.; Feng, Y.S.; Buchholz, M.; Kazis, L.E.; Kohlmann, T. Translation and adaptation of the German version of the Veterans Rand-36/12 Item Health Survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.V.A.; Garegnani, L.I.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Heldt, K.; Mumm, R.; Scheidt-Nave, C. Post-COVID-19 conditions in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of health outcomes in controlled studies. BMJ Med. 2024, 3, e000723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, I.-A.; Ansari, W.; Nguyen, J.L.; Mendes, D.; Ahmed, W.; Atkinson, J.; Scott, A.; Atwell, J.E.; Longworth, L.; Becker, F. Health-related quality of life in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in the UK: A cross-sectional study from pre- to post-infection. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, D.; Heinemann, S.; Heesen, G.; Hummers, E.; Schmachtenberg, T.; Dopfer-Jablonka, A.; Vahldiek, K.; Klawonn, F.; Klawitter, S.; Steffens, S.; et al. Association of long COVID with health-related Quality of Life and Social Participation in Germany: Finding from an online-based cross-sectional survey. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, H.; Wilton, J.; Tran, K.C.; Janjua, N.Z.; Levin, A.; Zhang, W. Long-term Health-related Quality of Life in Working-age COVID-19 Survivors: A Cross-sectional Study. Am. J. Med. 2024, 138, 850–861.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, B.; Inderyas, M.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Thapaliya, K.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Health-related quality of life in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Post COVID-19 Condition: A systematic review. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaira, L.A.; Gessa, C.; Deiana, G.; Salzano, G.; Maglitto, F.; Lechien, J.R.; Saussez, S.; Piombino, P.; Biglio, A.; Biglioli, F.; et al. The Effects of Persistent Olfactory and Gustatory Dysfunctions on Quality of Life in Long-COVID-19 Patients. Life 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapin, B.; Baker, S.; Thompson, N.; Li, Y.; Milinovich, A.; Lago, W.; Katzan, I. Pre-COVID health-related quality of life predicts symptoms and outcomes for patients with long COVID. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1581288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prazeres, F.; Romualdo, A.P.; Campos Pinto, I.; Silva, J.; Oliveira, A.M. The impact of long COVID on quality of life and work performance among healthcare workers in Portugal. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, M.; Vieux, L.; Kaiser, L.; Chappuis, F.; Chenaud, C.; Guessous, I. The longitudinal study of subjective wellbeing and absenteeism of healthcare workers considering post-COVID condition and the COVID-19 pandemic toll. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, B.; Li, Y.; Englund, K.; Katzan, I.L. Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome: Identification of Symptom Clusters and Predictors of Long-Term Outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, L.; Halfmann, M.; Castioni, N.; Kiefer, F.; König, S.; Schmieder, A.; Koopmann, A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental burden and quality of life in physicians: Results of an online survey. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1068715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, M.; Ullerich, H.; Zaruchas, A.; Meier, T.; Diller, R.; Pannewick, U.; Dhayat, S.A. Long-Term Quality of Life after COVID-19 Infection: Cross-Sectional Study of Health Care Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casjens, S.; Taeger, D.; Brüning, T.; Behrens, T. Changes in mental distress among employees during the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasmann, L.; Morawa, E.; Adler, W.; Schug, C.; Borho, A.; Geiser, F.; Beschoner, P.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Albus, C.; Weidner, K.; et al. Depression and anxiety among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal results over 2 years from the multicentre VOICE-EgePan study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 34, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, V.; Lieb, M.; Borho, A.; Morawa, E.; Geiser, F.; Beschoner, P.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Albus, C.; Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Baranowski, A.M.; et al. Psychological and Social Factors Associated With Reporting Post-COVID Symptoms Among German Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 4095–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number (n) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female Male | 686 148 | 82.3 17.7 |

| Age | <50 years ≥50 years | 301 533 | 36.1 63.9 |

| Occupation | Nurses Physicians Therapists Social service Administration Housekeeping Others | 486 92 60 36 36 32 92 | 58.3 11.0 7.2 4.3 4.3 3.8 11.0 |

| Workplace N.A. = 6 | Hospital Residential geriatric care Disability care Medical practice Outpatient care Other | 366 253 46 43 39 81 | 44.2 30.6 5.6 5.2 4.7 9.8 |

| Housing situation/ family status N.A. = 6 | Adults without children Adults with children Single | 463 239 126 | 55.9 28.9 15.2 |

| Smoking N.A. = 5 | Smoker | 88 | 10.6 |

| Obesity N.A. = 10 | BMI ≥ 30 | 191 | 23.2 |

| Clinically diagnosed pre-conditions | 544 | 65.2 | |

| Pre-existing diseases | Cardiovascular disease Hormonal/metabolic disease Skin disease Respiratory disease Mental disorder Urogenital disease | 243 198 112 107 84 32 | 29.1 23.7 13.4 12.8 10.1 3.8 |

| Health status before COVID-19 N.A. = 9 | Good moderate poor | 681 122 22 | 82.5 14.8 2.7 |

| Severe acute COVID-19 symptoms | 612 | 73.4 | |

| COVID-19 hospitalisation | 72 | 8.6 | |

| Post-COVID-19 symptoms in T4 | Symptoms present No symptoms No clear classification | 455 270 109 | 54.6 32.4 13.1 |

| Time T4 | All (N = 725 *) | Post-COVID-19 Symptoms (n = 455) | No Symptoms (n = 270) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, mean ± SD | Median, mean ± SD | Median, mean ± SD | p-value | |

| Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) | ||||

| Physical HRQoL | 43.7/42.8 ± 10.4 | 39.0/38.6 ± 9.6 | 51.9/50.0 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Mental HRQoL | 44.7/44.0 ± 11.7 | 38.9/40.4 ± 11.4 | 52.8/50.1 ± 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Mental Health | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.0/1.5 ± 1.4 | 2.0/2.0 ± 1.4 | 1.0/0.9 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 1.0/1.4 ± 1.5 | 2.0/1.8 ± 1.5 | 0.0/0.7 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms of Depression (0–6) | Symptoms of Anxiety (0–6) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | p-value | Mean | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Time | T1 T2 T3 T4 | 2.09 2.17 2.20 2.26 | 1.86–2.33 1.94–2.41 1.96–2.43 2.03–2.50 | 0.007 | 2.44 2.47 2.55 2.58 | 2.16–2.73 2.18–2.75 2.27–2.83 2.30–2.86 | 0.034 |

| Sex | Female Male | 2.16 2.21 | 1.93–2.38 1.93–2.49 | 0.645 | 2.55 2.47 | 2.28–2.82 2.15–2.80 | 0.509 |

| Age | <50 years ≥50 years | 2.15 2.21 | 1.89–2.41 1.98–2.44 | 0.502 | 2.44 2.58 | 2.14–2.74 2.30–2.86 | 0.127 |

| Occupation | Nurses Physicians Therapists Administration Social service Others | 2.27 1.71 2.13 2.14 2.63 2.21 | 2.04–2.49 1.41–2.02 1.77–2.49 1.70–2.58 2.19–3.06 1.93–2.50 | <0.001 | 2.42 2.22 2.43 2.66 2.85 2.49 | 2.15–2.69 1.86–2.57 2.03–2.83 2.16–3.15 2.38–3.32 2.16–2.82 | 0.166 |

| Obesity | yes no | 2.27 2.09 | 2.00–2.54 1.86–2.32 | 0.066 | 2.61 2.41 | 2.29–2.92 2.14–2.69 | 0.063 |

| Smoking | Smoker Non-smoker | * | 2.68 2.34 | 2.33–3.03 2.08–2.60 | 0.017 | ||

| Pre-existing mental illness | yes no | 2.65 1.72 | 2.35–2.95 1.49–1.94 | <0.001 | 3.09 1.93 | 2.75–3.43 1.65–2.21 | <0.001 |

| Pre-existing skin disease | yes no | * | 2.60 2.42 | 2.27–2.93 2.15–2.69 | 0.152 | ||

| Health status before COVID-19 | good moderate poor | 1.84 2.04 2.66 | 1.65–2.03 1.79–2.30 2.16–3.16 | 0.002 | 2.05 2.24 3.24 | 1.81–2.29 1.94–2.54 2.70–3.79 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peters, C.; Dulon, M.; Schablon, A.; Kersten, J.F.; Nienhaus, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health Among Employees in Health and Social Services—A Longitudinal Study. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060138

Peters C, Dulon M, Schablon A, Kersten JF, Nienhaus A. Impact of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health Among Employees in Health and Social Services—A Longitudinal Study. Infectious Disease Reports. 2025; 17(6):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060138

Chicago/Turabian StylePeters, Claudia, Madeleine Dulon, Anja Schablon, Jan Felix Kersten, and Albert Nienhaus. 2025. "Impact of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health Among Employees in Health and Social Services—A Longitudinal Study" Infectious Disease Reports 17, no. 6: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060138

APA StylePeters, C., Dulon, M., Schablon, A., Kersten, J. F., & Nienhaus, A. (2025). Impact of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and Mental Health Among Employees in Health and Social Services—A Longitudinal Study. Infectious Disease Reports, 17(6), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17060138