Severe Rectal Syphilis in the Setting of Profound HIV Immunosuppression: A Case Report Highlighting ERG/CD38 Immunophenotyping and a Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. History and Presentation

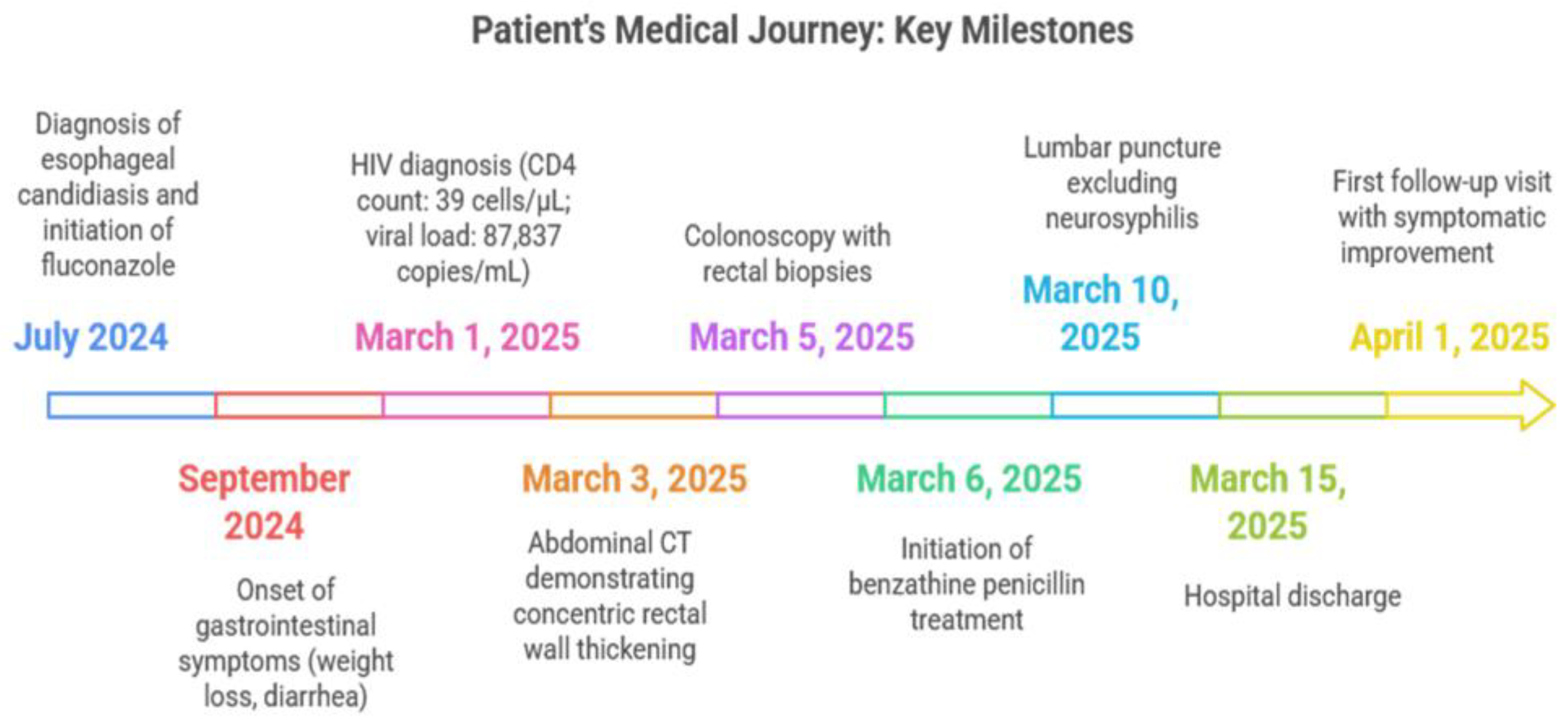

2.2. Key Timeline of Events

2.3. Initial Evaluation

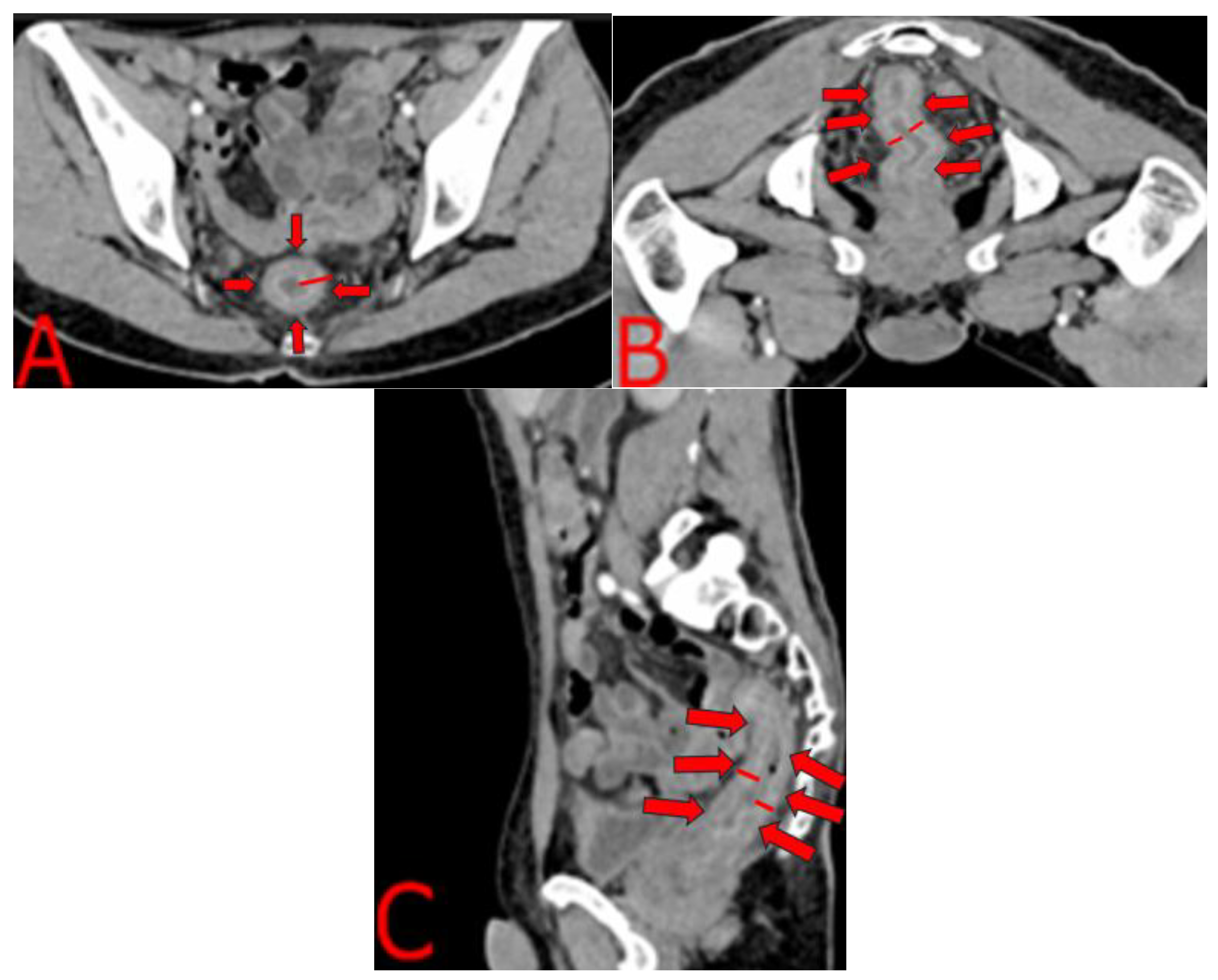

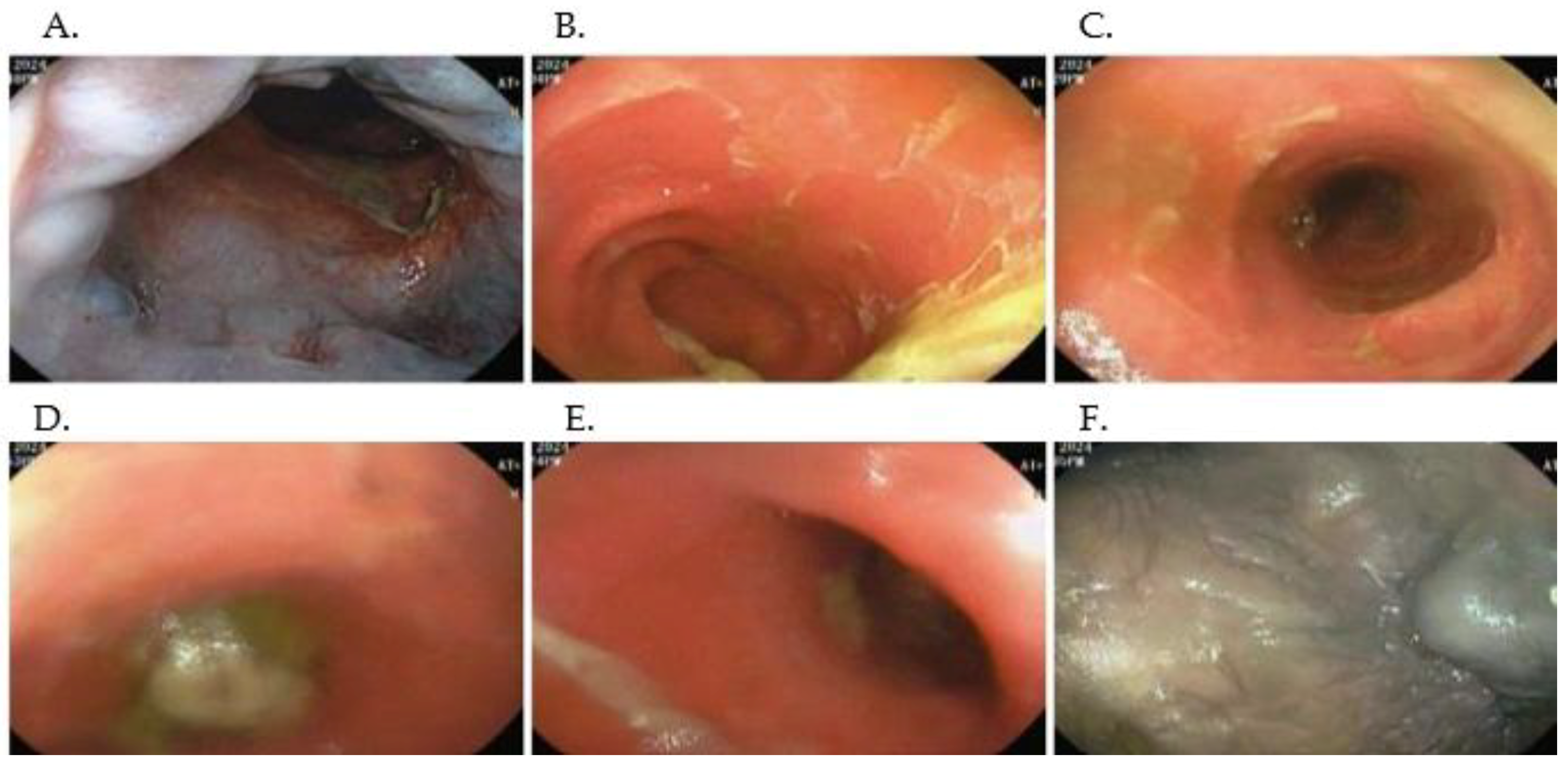

2.4. Imaging and Endoscopic Findings

2.5. Microbiological and Histopathological Workup

2.6. Treatment and Prophylaxis

2.7. Additional Investigations and Management

2.8. Antiretroviral Therapy and Outcome

3. Discussion

3.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance

3.2. Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

3.3. Comparative Case Analysis

3.4. Diagnostic Workup and Histopathology

3.5. Management and Follow-Up

3.6. Lessons Learned and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ab | antibody |

| ART | antiretroviral therapy |

| AZM | azithromycin |

| BID | twice daily |

| CD4 | cluster of differentiation 4 |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | computed tomography |

| Dox | doxycycline |

| d | days |

| EIA | enzyme immunoassay |

| ERG | ETS-related gene |

| FTA ABS | fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin stain |

| HRA | high-resolution anoscopy |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| IM | intramuscular |

| M | male |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSM | men who have sex with men |

| NL | normal |

| NS | not stated |

| PCN G | penicillin G |

| PET FDG | positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose |

| RPR | rapid plasma reagin |

| TMP/SMX | trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| TPHA | Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay |

| Trep EIA | treponemal enzyme immunoassay |

| TPPA | Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay |

| VDRL | Venereal Disease Research Laboratory |

| WS stain | Warthin–Starry stain |

| Wt loss | weight loss |

| ↑ diarrhea | increased diarrhea |

| hematemesis | vomiting of blood |

| wk | week |

References

- Afzal, Z.; Hussein, A.; O’Donovan, M.; Bowden, D.; Davies, R.J.; Buczacki, S. Diagnosis and Management of Rectal Syphilis—Case Report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 2024, rjac102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Attar, B.M.; Mutneja, H.R.; Majeed, M.; Randhawa, T.; Omar, Y.A.; Chicas, O.A.R. 1456 A Case of Syphilitic Proctitis in a Newly Diagnosed Patient With HIV. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, S807–S808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Arias, J.A.; Vidales-Silva, M.; Ocampo-Ramírez, A.; Higuita-Gutiérrez, L.F.; Cataño-Correa, J. Prevalence of HIV, Treponema Pallidum and Their Coinfection in Men Who Have Sex with Men, Medellín-Colombia. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 2024, 16, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmi, S.S.H.; Achuo-Egbe, Y.N.; Daid, S.G.S.; Dimino, J.; Shady, A.; Khan, G.M. S2776 Syphilitic Proctitis Mimicking Ulcerative Colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, e1819–e1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Liu, G.; Xu, J.; Luo, J.; Peng, L.; Ding, Y.; Shi, W. Syphilitic Proctitis:A Case Report and Review of theLiterature. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2024, 16, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajal, D.; Lambert, K.; Hamed, A.; Movahed, H. S1854 Syphilitic Proctitis: A Rectal Cancer Mimic. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, S816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona Arias, J.; Higuita-Gutiérrez, L.F.; Cataño-Correa, J.C. Prevalencia de infección por Treponema pallidum en individuos atendidos en un centro especializado de Medellín, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Pública 2022, 40, e343212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, Y.A.; Restrepo, A.J.; Martinez, J.D.; Rey, M.H.; Marulanda, J.C.; Molano, J.C.; Garzon Olarte, M. Coexistencia de sida y proctitis ulcerativa en un paciente colombiano. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 2006, 21, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Peine, B.S.; Ved, K.J.; Fleming, T.; Sun, Y.; Honaker, M.D. Syphilitic Proctitis Presenting as Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Case Report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 107, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Pinho, R.; Rodrigues, A. Infectious Proctitis Due to Syphilis and Chlamydia: An Exuberant Presentation. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2019, 111, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, R.; Hashim, P.W.; Reddy, V.B.; Einarsdottir, H.; Longo, W. Sexually Transmitted Infections of the Anus and Rectum. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, M.M.; Whitlow, C.B. Sexually Transmitted and Anorectal Infectious Diseases. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 42, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-Y.; Wang, J. Primary Syphilitic Proctitis Associated with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in a Male Patient Who Had Sex with Men: A Case Report. J. Mens. Health 2021, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, I.; Wang, G.; Grennan, T. Syphilis Proctitis: An Uncommon Presentation of Treponema Pallidum Mimicking Malignancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2025, 18, e263948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, C.M.; Hook, E.W., III; Shepherd, M.; Verley, J.; Rompalo, A.M. Altered Clinical Presentation of Early Syphilis in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, R.; Jiménez-Oñate, F.; Aguilar, M.; Galindo, M.J.; Rivas, P.; Ocampo, A.; Berenguer, J.; Arranz, J.A.; Ríos, M.J.; Knobel, H.; et al. Impact of Syphilis Infection on HIV Viral Load and CD4 Cell Counts in HIV-Infected Patients. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2007, 44, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E.L.; Spudich, S.S. Neurosyphilis and the Impact of HIV Infection. Sex. Health 2015, 12, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Jaime, F.; Paniagua, C.S.; Balén, M.B. Primary Chancre in the Rectum: An Underdiagnosed Cause of Rectal Ulcer. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017, 109, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretti, A.P.; Virdis, M.; Maroni, N.; Arena, M.; Masci, E.; Magenta, A.; Opocher, E. The Great Pretender: Rectal Syphilis Mimic a Cancer. Case Rep. Surg. 2015, 2015, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Yanagisawa, N.; Suganuma, A.; Imamura, A.; Ajisawa, A. Syphilis proctitis complicated with HIV infection: A case report. J. Jpn. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 2012, 86, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.A.; Calixto, N.N.; Cárdenas, G.V.; García, C.C. Rectal Syphilis in a HIV Patient from Peru. Rev. Gastroenterol. Perú 2018, 38, 381–383. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Artunduaga-Cañas, E.; Vidal-Cañas, S.; Pérez-Garay, V.; Valencia-Ibarguen, J.; Lopez-Muñoz, D.F.; Liscano, Y. First Report from Colombia of a Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Kluyvera Ascorbata Exhibiting an AmpC Resistance Pattern: A Case Report. Diseases 2025, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, J.F.; Diaz-Diaz, M.Á.; Vidal-Cañas, S.; Urriago, G.; Correa, V.; Melo-Burbano, L.Á.; Liscano, Y. Postoperative Empyema Due to Leclercia Adecarboxylata Following Mesothelioma Surgery: A Case Report. Pathogens 2025, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos, M.; Aristizabal, Y.; Aragón-Muriel, A.; Oñate-Garzón, J.; Liscano, Y. Characterization and Classification In Silico of Peptides with Dual Activity (Antimicrobial and Wound Healing). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Sanchez, S.P.; Ocampo-Ibáñez, I.D.; Liscano, Y.; Martínez, N.; Muñoz, I.; Manrique-Moreno, M.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Oñate-Garzon, J. Integrating In Vitro and In Silico Analysis of a Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Interaction with Model Membranes of Colistin-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Location | Age/Sex | Clinical Background | HIV Status | Symptom Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work (2025) | Universidad Santiago de Cali & Clínica de Occidente, CALI, CO | 46 M (MSM) | Erosive antral gastritis; esophageal candidiasis (2024) | New HIV (CD4 39 cells/µL; VL 87,837 copies/mL) | 6 months |

| Díaz-Jaime et al. (2017) [18] | La Fe Hospital, Valencia, Spain | 35 M (MSM) | Known HIV; no other comorbidities | Not specified | 2 weeks |

| Pisani et al. (2015) [19] | Univ. of Milan, Milan, Italy | 48 M (MSM) | No prior history; monogamous MSM relationship | Not specified | Few weeks |

| Kobayashi et al. (2012) [20] | Tokyo Univ. Hosp., Tokyo, Japan | 26 M (MSM) | Newly diagnosed HIV at presentation | CD4 227 cells/µL; not on ART | Several weeks |

| Figueroa et al. (2018) [21] | Specialized Ctr., Lima, Peru | 53 M (MSM) | No known HIV until workup; prior painless chancre | New HIV CD4 275 cells/µL | ~3 months |

| Chen and Wang (2021) [13] | Municipal Hosp., Hangzhou, China | 31 M (MSM) | Newly diagnosed HIV; multiple anonymous partners | HIV−1 Ab +; CD4% 15.9% | ~2 months |

| Hunter I et al. (2025) [14] | Vancouver, Canada | 60 s M | Previously healthy; condomless receptive anal sex with casual partner | HIV−; negative serology | >3 months |

| Afzal Z et al. (2024) [1] | Cambridge, UK | 64 M | Diverticular disease; multiple MSM partners (elicited later) | HIV−; negative serology | Several weeks |

| Author (Year) | Key Manifestations | Biopsy Highlight | Imaging Brief | Serology | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work (2025) | Wt loss, ↑diarrhea, hematemesis, fever, pain | ERG+ capillaries; CD38+ plasma cells | CT “target sign”; colonoscopy: exudates, ulcers | Trep-EIA+; VDRL 1:64 | PCN G IM × 3 wk + TMP/SMX and AZM + Dox + ART |

| Díaz-Jaime et al. (2017) [18] | Hematochezia, rectal mass | Plasma-cell-rich; spirochetes (WS stain) | Endoscopic ulcer only | TPHA+; RPR+ | PCN G IM (single dose) |

| Pisani et al. (2015) [19] | Rectal bleeding; palpable 3 cm mass | WS stain + spirochetes | Colon ulcer; MRI T3N+; PET FDG+ | Trep+; HSV/CMV/HHV-8- | PCN G 2.4 M IU IM × 1 |

| Kobayashi et al. (2012) [20] | Anal pain, bleeding, palm/sole rash | Deep ulcer; no organisms on H&E | Endoscopic deep ulcer | FTA-ABS+; RPR NS | IV PCN G (dose unspecified) |

| Figueroa et al. (2018) [21] | Tenesmus, bleeding, pain, lymphadenopathy | Granulomatous infiltrate; spirochetes | Deep ulcer + multiple erosions | VDRL–; FTA-ABS+ | PCN G IM × 1 + ART |

| Chen and Wang (2021) [13] | Tenesmus, mucous discharge, rash | Plasma cell infiltrate; T. pallidum IHC+ | Sigmoidoscopy: superficial ulcers | TPPA 1:1280; RPR 1:256 | PCN G IM × 3 wk + ART |

| Hunter I et al. (2025) [14] | Verrucous lesions, pain, bleeding | Psoriasiform hyperplasia; ERG+, CD38+ | HRA: friable, hyperaemic mass | EIA+; TPPA+; RPR 1:4096 | Doxy 100 mg BID × 14 d |

| Afzal Z et al. (2024) [1] | Bowel habit change; mass; cutaneous lesions | Chronic proctitis; spirochetes (Steiner) | CT: mild thickening + nodes; MRI NL | EIA+; TPPA+; RPR 1:128 | Oral PCN G course (14 d) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carmona Valencia, D.M.; López, J.D.; Correa Forero, S.V.; Bonilla Bonilla, D.M.; Assis, J.K.; Liscano, Y. Severe Rectal Syphilis in the Setting of Profound HIV Immunosuppression: A Case Report Highlighting ERG/CD38 Immunophenotyping and a Review of the Literature. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17040085

Carmona Valencia DM, López JD, Correa Forero SV, Bonilla Bonilla DM, Assis JK, Liscano Y. Severe Rectal Syphilis in the Setting of Profound HIV Immunosuppression: A Case Report Highlighting ERG/CD38 Immunophenotyping and a Review of the Literature. Infectious Disease Reports. 2025; 17(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarmona Valencia, Diana Marcela, Juan Diego López, Shirley Vanessa Correa Forero, Diana Marcela Bonilla Bonilla, Jorge Karim Assis, and Yamil Liscano. 2025. "Severe Rectal Syphilis in the Setting of Profound HIV Immunosuppression: A Case Report Highlighting ERG/CD38 Immunophenotyping and a Review of the Literature" Infectious Disease Reports 17, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17040085

APA StyleCarmona Valencia, D. M., López, J. D., Correa Forero, S. V., Bonilla Bonilla, D. M., Assis, J. K., & Liscano, Y. (2025). Severe Rectal Syphilis in the Setting of Profound HIV Immunosuppression: A Case Report Highlighting ERG/CD38 Immunophenotyping and a Review of the Literature. Infectious Disease Reports, 17(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr17040085