Abstract

Background: Peripancreatic collections (PPCs) are a frequent and severe complication of acute and chronic pancreatitis, as well as pancreatic surgery, often requiring interventions to treat and prevent infection, gastric obstruction, and other complications. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative to surgical and percutaneous approaches, offering reduced morbidity and shorter recovery times. However, the effectiveness of EUS-guided drainage in post-surgical PPCs remains underexplored. Methods: This retrospective, single-center study evaluated the technical and clinical outcomes of EUS-guided drainage in patients with PPCs between October 2021 and December 2024. Patients were categorized as having post-pancreatitis or post-surgical PPCs. Technical success, clinical success, complications, recurrence rates, and the need for reintervention were assessed. Results: A total of 50 patients underwent EUS-guided drainage, including 42 (84%) with post-pancreatitis PPCs and 8 (16%) with post-surgical PPCs. The overall technical success rate was 100%, with clinical success achieved in 96% of cases. Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) were used in 84% of patients, including 7.1% as a dual-gate salvage strategy after the failure of double-pigtail drainage. The complication rate was 24%, with infection being the most common (16%). The recurrence rate was 25%, with no significant difference between post-pancreatitis and post-surgical cases. Patients with walled-off necrosis had a significantly higher reintervention rate (35%) than those with pseudocysts (18%; p = 0.042). Conclusions: EUS-guided drainage is a highly effective and safe intervention for PPCs, including complex post-surgical cases. The 100% technical success rate reinforces its reliability, even in anatomically altered post-surgical collections. While recurrence rates remain a consideration, EUS-guided drainage offers a minimally invasive alternative to surgery, with comparable outcomes in both post-pancreatitis and post-surgical patients. Future multi-center studies should focus on optimizing treatment strategies and reducing recurrence in high-risk populations.

1. Introduction

Peripancreatic collections (PPCs) are common and serious complications of acute and chronic pancreatitis, affecting up to 40% of patients with severe acute pancreatitis [1]. These collections can lead to considerable morbidity, causing infections, persistent abdominal pain, biliary and gastric outlet obstruction, and even sepsis if not treated [2]. Managing PPCs poses a major therapeutic challenge due to their heterogeneous nature, variable clinical course, and risk of recurrence despite intervention. The management of PPCs relies on several factors, including their composition (necrotic vs. non-necrotic), size, symptoms, and risk of infection. While some collections may resolve on their own, symptomatic and infected PPCs require intervention to avoid complications such as superinfection, rupture, or bleeding. Traditionally, surgical drainage was the standard of care, but it came with high morbidity and extended hospital stays [3]. Over the past two decades, minimally invasive techniques, particularly endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage, have emerged as a first-line approach, offering lower complication rates and shorter recovery times. EUS-guided drainage has revolutionized PPC management [4]. This method allows for direct transmural drainage into the gastrointestinal lumen using plastic or metal stents, often eliminating the need for surgery. Endoscopic necrosectomy has further enhanced treatment options for infected walled-off necrosis, reducing the need for open or percutaneous surgical debridement [3,4,5]. Multiple studies have shown high clinical success rates, less morbidity, and shorter length of hospital stay for endoscopic interventions.

The evolution of PPC classification has also played a central role in optimizing treatment strategies. The original 1992 Atlanta classification provided a framework for defining PFCs, which was later revised in 2012 to include four distinct types: acute peripancreatic fluid collections, pancreatic pseudocysts, acute necrotic collections (ANCs), and walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) [6]. These categories consider the collection’s time-based development and the presence of necrotic material, guiding therapeutic decision-making. Recent studies underscore the importance of intervention based on symptoms rather than solely on size, leading to a paradigm shift in clinical management [7].

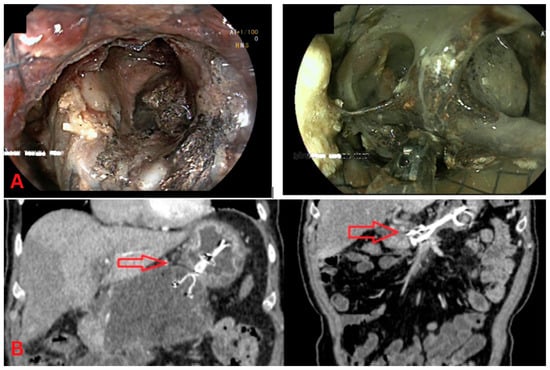

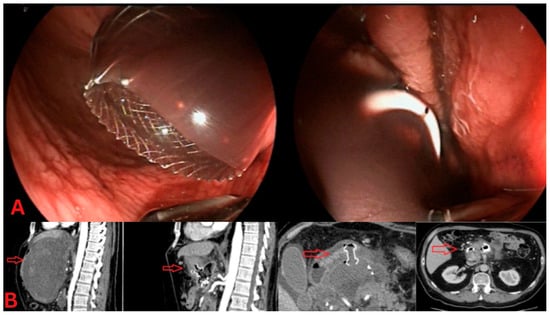

Among PPCs, WOPN presents a significant challenge due to solid necrotic debris, which often necessitates direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) (Figure 1). Using lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) has proven beneficial in facilitating more effective drainage and providing access for necrosectomy [8]. Furthermore, the multiple transluminal gateways technique (MTGT) [9] and dual-modality drainage, which combines percutaneous and endoscopic approaches, have been explored to enhance treatment efficacy [10], especially in cases complicated by disconnected duct syndrome (DDS) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN). (A) Endoscopic view: This image shows direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) from walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN). The necrotic tissue is visualized through the endoscope, with a clear opening into the cavity containing necrotic material. (B) CT imaging: The left CT scan shows a sizeable peripancreatic collection before DEN, with encapsulated fluid and necrotic debris (red arrow). The CT scan on the right demonstrates the post-procedural imaging after DEN, showing a significant reduction in the collection and improved drainage.

Figure 2.

Dual-gate drainage for peripancreatic collections. (A) Endoscopic view: The left panel shows a lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) placed for drainage of a sizeable peripancreatic collection, providing a wide conduit for necrotic material to exit. The right panel displays a double-pigtail plastic stent, placed as a secondary drainage method, to offer additional decompression of the collection. (B) CT imaging: The sagittal CT view (left) highlights a dual-gate drainage approach, with a visible LAMS (red arrow) in place. The axial CT image (right) further illustrates the positioning of both the LAMS and pigtail stents, confirming adequate drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collection.

Despite the increasing implementation of endoscopic management, several questions remain regarding its comparative effectiveness across different types of peripancreatic collections, particularly between post-pancreatitis and post-surgical cases. While prior studies have evaluated outcomes for endoscopic drainage [11,12], limited data directly compare these two distinct patient groups in real-world clinical settings. Additionally, much of the existing literature focuses on short-term procedural success, with fewer studies examining long-term outcomes such as recurrence rates, delayed complications, and hospital readmissions. Understanding these differences is crucial for optimizing patient selection and procedural decision-making.

Another key area of interest is the variability in endoscopic techniques and their impact on treatment outcomes. Factors such as stent choice (LAMSs vs. plastic stents) and direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) may significantly influence success rates [8]. However, these aspects are not always standardized across studies. By assessing the effectiveness of various endoscopic strategies, our study aims to provide practical, evidence-based insights that can help refine treatment protocols.

This retrospective study evaluates the real-world effectiveness, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic interventions for PPCs. By analyzing a broad patient cohort that includes both post-pancreatitis and post-surgical cases, we aim to bridge the gap in the literature and provide valuable insights into procedural success rates, complication profiles, and predictors of treatment outcomes.

2. Methods

This study is a retrospective review conducted at a single tertiary referral center specializing in the management of pancreatic diseases. We examined patients who underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided (EUS-guided) drainage of peripancreatic collections between October 2021 and December 2024. Patients were included if they had imaging-confirmed peripancreatic collections (as confirmed by CT, MRI, or EUS) and underwent EUS-guided drainage. All collections were classified according to the Revised Atlanta Classification [6]. As all patients underwent drainage at least 4 weeks after onset, only late-phase collections were included: walled-off necrosis (WON), pancreatic pseudocysts, and post-surgical collections. Drainage was only performed for patients with symptomatic or infected collections. Patients with sterile necrosis without complications or collections in the setting of interstitial pancreatitis were omitted. Exclusion criteria included patients with unconfirmed diagnoses, incomplete records, or those who underwent surgical or percutaneous drainage without EUS-guided intervention. The procedure involved transgastric or transduodenal drainage guided by a linear-array echoendoscope, with the placement of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) or two double-pigtail plastic stents. The choice between lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) and plastic stents was based on multiple factors. Percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) was not performed in this cohort. At our center, endoscopic drainage is preferred for collections with mature walls and favorable anatomical proximity to the gastrointestinal lumen.

LAMSs were generally preferred for walled-off necrosis (WON), especially when significant solid debris was present, due to their larger diameter and ability to facilitate necrosectomy. In contrast, plastic stents were selected for uncomplicated pseudocysts or smaller fluid collections with minimal necrosis. Additional considerations included the size of the cavity, the maturity of the collection wall, and anatomical accessibility. Operator preference and stent availability also influenced the decision, particularly in urgent or after-hour cases. All procedures were performed under EUS guidance using either a freehand or wire-guided technique, at the discretion of the endoscopist. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) was performed on demand for collections with extensive necrosis. Primary outcomes included technical success (successful stent placement and resolution of the collection) and clinical success (resolution of symptoms without further intervention). Secondary outcomes included procedure-related complications (bleeding, infection, and stent migration), length of hospital stay, and recurrence rates within six months. Subgroup analysis was performed to compare outcomes between post-pancreatitis and post-surgical collections. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Comparisons between post-pancreatitis and post-surgical collections were made using the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of clinical success and the need for repeat interventions. The Pearson chi-square test was applied to evaluate whether post-surgical etiology was associated with a higher risk of recurrent collections requiring reintervention. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS v.19.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Between October 2021 and December 2024, 50 patients underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage for peripancreatic collections (PPCs) (Table 1). The median age of the cohort was 56 years (range: 34–90), with a male predominance of 56%. The primary etiology of PPCs was post-pancreatitis in 84% (n = 42) of cases, while 16% (n = 8) were post-surgical collections. The most common type of PPC was walled-off necrosis (WON) at 50%, followed by pancreatic pseudocysts at 32%, infected collections at 16%, and mixed-type collections at 2%. The median duration from diagnosis to intervention was 37 days (IQR: 21–64 days). Indications for drainage included persistent abdominal pain (78%), systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with suspected infection (24%), gastric outlet obstruction (12%), and biliary obstruction (10%).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

Among the 42 patients with post-pancreatitis collections, the severity of acute pancreatitis was classified as severe in 6 patients (14.3%) and moderately severe in 36 patients (85.7%), according to the Revised Atlanta Classification.

In the post-surgical group (n = 8), surgical procedures included central pancreatectomy (n = 1) and distal pancreatectomy (n = 7). Dual-gate drainage (placement of two stents into separate compartments of the collection) was performed in three patients overall, two with post-pancreatitis walled-off necrosis and one with a post-surgical collection, reflecting increased anatomical complexity and limited access in these cases. Detailed information regarding surgical drain management and postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) was not available in the retrospective records.

3.2. Technical and Clinical Success

The overall technical success rate of EUS-guided drainage was 100%, defined as the successful placement of transluminal stents with adequate fluid drainage and resolution of collections without the need for percutaneous or surgical intervention. Clinical success, defined as resolution of symptoms and radiologic improvement without the need for further intervention, was achieved in 96% of patients (95% CI: 86.5–98.9%) within the six-month follow-up period.

Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) were used in 42 of 50 patients (84%), with 3 cases (7.1%) requiring LAMS placement as a dual-gate salvage strategy due to a lack of clinical improvement following initial drainage with two double-pigtail plastic stents.

3.3. Complications and Need for Additional Interventions

Complications occurred in 24% of cases (95% CI: 14.3–37.4%) (Table 2), with secondary infection being the most common (16%, n = 8), followed by bleeding (4%, n = 2). All were managed conservatively or endoscopically without the need for surgical conversion. Notably, no cases of stent migration were observed during the study period.

Table 2.

Confidence intervals for key outcomes.

Reintervention was required in 24% of cases (95% CI: 14.3–37.4%), most commonly among patients with WON (35%) compared to pseudocysts (18%), reflecting the increased procedural complexity associated with necrotic collections (p = 0.042). The mean time to secondary intervention (direct endoscopic necrosectomy) was 12 days (IQR: 8–22 days) following the initial procedure.

3.4. Outcomes in Post-Surgical vs. Post-Pancreatitis Collections

Among the eight patients with post-surgical peripancreatic collections (16% of the cohort), technical success, like clinical success, was observed in 100% of cases by final follow-up. However, post-surgical collections demonstrated a higher rate of repeat endoscopic interventions (25%) compared to post-pancreatitis collections (19%) (p < 0.001). The median duration of stent placement was significantly longer in the post-surgical group (42 days) compared to the post-pancreatitis group (28 days) (p = 0.021). Despite these differences, overall complication rates and long-term clinical success were comparable between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes between post-pancreatitis and post-surgical PPCs.

3.5. Predictors of Outcome and Recurrence Rates

Univariate analysis identified post-surgical etiology as a significant predictor for the need for repeat interventions (χ2 = 23.12, p < 0.05). Neither age nor sex was significantly associated with treatment success or recurrence. The recurrence rate of peripancreatic collections was 24% (95% CI: 14.3–37.4%), and this was more frequently observed in patients with walled-off necrosis (30%) compared to pseudocysts (12%, p = 0.038). All recurrences were managed successfully with repeat EUS-guided drainage, and no patients required surgical intervention. The median time to recurrence was 12 days.

3.6. Long-Term Outcomes and Follow-Up

At the six-month follow-up, 96% of patients remained asymptomatic, with no evidence of recurrence. Patients who achieved clinical resolution reported significant improvement in nutritional status and overall quality of life. There were no procedure-related mortalities, and no patients required surgical salvage procedures.

4. Discussion

A key strength of this study is the inclusion of post-surgical peripancreatic collections (PPCs) and post-pancreatitis collections, making it one of the few retrospective studies to evaluate and compare outcomes across these distinct clinical scenarios. While most studies on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage have focused on PPCs secondary to acute necrotizing pancreatitis, post-surgical collections remain underrepresented despite their distinct pathophysiology, higher recurrence risk, and potential need for prolonged drainage [13]. By incorporating a heterogeneous patient cohort, our study provides valuable real-world insights into the applicability and efficacy of EUS-guided drainage across both post-pancreatitis and post-surgical cases. The 100% technical success rate reinforces the reliability and feasibility of EUS-guided drainage, even in the more complex subset of post-surgical PPCs, where anatomical alterations, fibrotic changes, and fistula formation can make endoscopic intervention technically challenging. Despite these challenges, our findings suggest that EUS-guided drainage remains highly effective and durable for post-surgical collections, with outcomes comparable to those in post-pancreatitis PPCs. Another strength of this study is its real-world applicability, as it reflects outcomes in a heterogeneous patient population managed in routine clinical practice rather than controlled trial settings. Many previous studies have excluded post-surgical patients, leading to limited guidance on the optimal management approach for this subgroup. Our study contributes to the limited body of evidence by demonstrating that EUS-guided drainage appears to be a feasible, safe, and effective option in selected patients with post-surgical peripancreatic collections. While encouraging, these findings require validation in larger, prospective studies before firm treatment recommendations can be made.

We did not stratify outcomes based on the timing of intervention (i.e., before or after 28 days). However, this distinction has been associated with differences in complication rates, particularly in cases of sterile necrosis. Given that our median time to drainage was 37 days, most patients underwent late-phase intervention. Future studies should investigate how timing affects outcomes, particularly the risk of infection or procedural failure in early attempts at drainage.

The 100% technical success rate observed in our study is consistent with previous reports demonstrating the high feasibility of EUS-guided drainage when performed by experienced endoscopists [14,15]. However, few studies have addressed post-surgical PPCs, making direct comparisons difficult. Our findings suggest that EUS-guided drainage can be just as effective for post-surgical collections as for post-pancreatitis collections, which is an essential contribution to the literature. Additionally, our 96% clinical success rate aligns with previously reported success rates ranging between 85% and 97% in meta-analyses focusing on post-pancreatitis PPCs [4]. However, the recurrence rate of 25% in our study is slightly higher than in some reports [16], likely due to the inclusion of post-surgical patients, who are known to have a higher risk of recurrence due to persistent pancreatic fistulas or altered anatomy. This finding underscores the need for tailored management strategies in post-surgical cases, including potential prolonged stent placement or additional interventions to optimize outcomes, such as directed treatment to the disrupted pancreatic duct [17].

The inclusion of post-surgical PPCs in this study has significant clinical implications. It suggests that EUS-guided drainage should be considered the preferred treatment modality for these cases, rather than defaulting to surgical or percutaneous approaches [18]. Traditionally, surgical drainage has been the standard for post-surgical collections, particularly in patients with anastomotic leaks or complex fistula formations [19]. However, our findings indicate that EUS-guided drainage is a minimally invasive, safe, and highly effective alternative, potentially reducing the need for reoperations and shortening hospital stays. For patients with post-surgical collections, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage offers multiple benefits over traditional techniques: 1. Its minimally invasive approach reduces extra surgical trauma for at-risk patients. 2. There is less morbidity compared to open or laparoscopic drainage methods [20]. 3. It allows for repeat procedures, making step-up management easier when necessary. 4. Patients typically experience shorter hospital stays, as endoscopic methods enable faster recovery than conventional surgery procedures.

Given the increasing evidence supporting EUS-guided drainage for PPCs, our study further supports its expansion into more complex cases, including post-surgical collections, where guidance is generally lacking.

We use the term “real-world” to describe the inclusion of an unselected, consecutive patient cohort treated in routine clinical settings, without strict eligibility criteria or protocolized interventions. This design reflects typical clinical decision-making and enhances the external validity of our findings, though it also introduces variability in treatment technique and timing.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. As a retrospective single-center study, findings may not be generalizable to all patient populations or reflect variations in procedural expertise across different institutions. The cohort size, while sufficient for meaningful analysis, remains limited, particularly regarding the small number of patients with post-surgical collections (n = 8), which restricts the ability to draw firm conclusions for this subgroup. Additionally, heterogeneity in procedural techniques, including differences in stent selection, timing of necrosectomy, and duration of drainage, may have influenced outcomes.

Another limitation is the relatively short follow-up period of six months, which may not fully capture late complications such as recurrent fluid collections, delayed stent-related adverse events, or the development of pancreatic fistulas, especially in patients with altered postoperative anatomy or disconnected duct syndrome.

Another significant limitation is the potential for selection bias. Only patients undergoing EUS-guided drainage were included, while those managed conservatively, percutaneously, or surgically were excluded. Although this study did not include a surgical comparator group, prior studies have shown that step-up surgical strategies can achieve durable outcomes. For instance, Pavlek et al. [21] reported comparable clinical success and improved long-term pancreatic function using a minimally invasive step-up approach in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. The absence of a comparison group treated with surgical or percutaneous drainage limits the ability to directly assess the relative efficacy of EUS-guided drainage in post-surgical cases. Future studies should include prospective, multi-center trials to compare outcomes across drainage modalities and refine treatment algorithms in this complex patient population.

Future Research Directions

Future research should focus on prospective multi-center trials to confirm these findings and explore standardized treatment protocols for post-surgical PPCs. Investigations into optimal stent dwell time, ideal patient selection criteria for necrosectomy, and novel adjunctive therapies (e.g., enzymatic debridement [22] and irrigation techniques [23]) may help optimize outcomes. Additionally, studies assessing the long-term quality of life, cost-effectiveness, and comparative effectiveness of EUS-guided drainage against surgical approaches would provide valuable insights into the broader clinical impact of this approach.

Due to the higher recurrence rate observed in post-surgical collections, upcoming research should investigate strategies such as prolonged stent placement to minimize recurrence, supplementary endoscopic treatments (e.g., dual-modality drainage) for complex post-surgical cases, and predictive models to identify patients at increased risk of recurrence and customize interventions accordingly.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage for peripancreatic collections (PPCs), including post-surgical cases, in a real-world setting. The 100% technical success rate confirms the feasibility of this minimally invasive approach, while the 96% clinical success rate and low complication rates further support its effectiveness. A key strength of this study is the inclusion of post-surgical collections, a challenging and often underrepresented group, demonstrating that EUS-guided drainage is as effective in these cases as in those involving post-pancreatitis collections.

Our findings support the feasibility of EUS-guided drainage as a potential first-line approach in selected post-surgical patients; however, prospective validation is still needed. While the 25% recurrence rate emphasizes the need for tailored management strategies, such as prolonged stent placement, this study reinforces the role of EUS as a preferred treatment option.

Despite the retrospective, single-center design, our results provide valuable real-world data that supports EUS as the standard of care for PPCs. Future multi-center trials should further refine treatment strategies, optimize patient selection, and explore methods to reduce recurrence, particularly in post-surgical cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. and P.I.K.; methodology, N.S. and P.I.K.; validation, N.S. and P.I.K.; formal analysis, N.S. and P.I.K.; investigation, N.S. and P.I.K.; resources, N.S. and P.I.K.; data curation, N.S. and P.I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, N.S. and P.I.K.; visualization, N.S. and P.I.K.; supervision, P.I.K.; project administration, N.S. and P.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of Acibadem City Clinic, Tokuda University Hospital EAD (Statement No 65, approval date 16 June 2025, application No: 07/11.06.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, as the research involved analysis of pre-existing anonymized patient data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PPCs | Peripancreatic collections |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| LAMS | Lumen-apposing metal stents |

| WON | Walled-off necrosis |

| DEN | Direct endoscopic necrosectomy |

| MTGT | Multiple transluminal gateway technique |

| DDS | Disconnected duct syndrome |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| SIRS | Systemic inflammatory response syndrome |

References

- Trikudanathan, G.; Wolbrink, D.R.J.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Mallery, S.; Freeman, M.; Besselink, M.G. Current Concepts in Severe Acute and Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1994–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.-Y. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: Experience from 643 patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besselink, M.G.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Nieuwenhuijs, V.B.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Buskens, E.; Dejong, C.H.; van Eijck, C.H.; van Goor, H.; Hofker, S.S.; et al. Minimally invasive “step-up approach” versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): Design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN13975868]. BMC Surg. 2006, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brunschot, S.; van Grinsven, J.; Voermans, R.P.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bouwense, S.A.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Transluminal endoscopic step-up approach versus minimally invasive surgical step-up approach in patients with infected necrotising pancreatitis (TENSION trial): Design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN09186711]. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onnekink, A.M.; Boxhoorn, L.; Timmerhuis, H.C.; Bac, S.T.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bouwense, S.A.W.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Endoscopic Versus Surgical Step-Up Approach for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis (ExTENSION): Long-term Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.G.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Vege, S.S. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyberg, A.; Karia, K.; Gabr, M.; Desai, A.; Doshi, R.; Gaidhane, M.; Sharaiha, R.Z.; Kahaleh, M. Management of pancreatic fluid collections: A comprehensive review of the literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, N.; Kozarek, R.; Kanji, Z.; Ross, A.; Gluck, M.; Gan, S.; Larsen, M.; Irani, S. Do lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) improve treatment outcomes of walled-off pancreatic necrosis over plastic stents using dual-modality drainage? Endosc. Int. Open 2017, 5, E1052–E1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajulu, S.; Phadnis, M.A.; Christein, J.D.; Wilcox, C.M. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 74, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluck, M.; Ross, A.; Irani, S.; Lin, O.; Gan, S.I.; Fotoohi, M.; Hauptmann, E.; Crane, R.; Siegal, J.; Robinson, D.H.; et al. Dual Modality Drainage for Symptomatic Walled-Off Pancreatic Necrosis Reduces Length of Hospitalization, Radiological Procedures, and Number of Endoscopies Compared to Standard Percutaneous Drainage. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012, 16, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.B.; Kwon, J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Hwang, D.W.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, M.-H.; Lee, S.K.; Seo, D.-W.; Lee, S.S.; et al. The treatment indication and optimal management of fluid collection after laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, A.C.; Levy, M.J.; Kaura, K.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Cleary, S.P.; Kendrick, M.L.; Truty, M.J.; Vargas, E.J.; Topazian, M.; Chandrasekhara, V. Acute and early EUS-guided transmural drainage of symptomatic postoperative fluid collections. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coté, G.A. Treatment of postoperative pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.Y.; Arnoletti, J.P.; Holt, B.A.; Sutton, B.; Hasan, M.K.; Navaneethan, U.; Feranec, N.; Wilcox, C.M.; Tharian, B.; Hawes, R.H.; et al. An Endoscopic Transluminal Approach, Compared with Minimally Invasive Surgery, Reduces Complications and Costs for Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderloni, A.; Fabbri, C.; Nieto, J.; Uwe, W.; Dollhopf, M.; Aparicio, J.R.; Perez-Miranda, M.; Tarantino, I.; Arlt, A.; Vleggaar, F.; et al. The safety and efficacy of a new 20-mm lumen apposing metal stent (lams) for the endoscopic treatment of pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections: A large international, multicenter study. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivian Lopes, C.; Pesenti, C.; Bories, E.; Caillol, F.; Giovannini, M. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, B.; Parlak, E.; Oguz, D.; Disibeyaz, S.; Koksal, A.S.; Sahin, B. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic fistulas. Surg. Endosc. 2006, 20, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, C.G.; Gervais, D.A.; Castillo, C.F.; Mueller, P.R.; Arellano, R.S. Interventional Radiology in the Management of Abdominal Collections After Distal Pancreatectomy: A Retrospective Review. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; Meredith, L.; Tham, E.; Yeo, T.P.; Bowne, W.B.; Nevler, A.; Yeo, C.J.; Lavu, H. Peripancreatic fluid collections following distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy—When is intervention warranted? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2024, 28, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, W.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, A. Endoscopic Versus Laparoscopic Treatment for Pancreatic Pseudocysts. Pancreas 2021, 50, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlek, G.; Romic, I.; Kekez, D.; Zedelj, J.; Bubalo, T.; Petrovic, I.; Deban, O.; Baotic, T.; Separovic, I.; Strajher, I.M.; et al. Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, M.; Tekin, A.; Kucukkartallar, T.; Vatansev, H.; Kartal, A. Enzymatic Debridement in Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Int. Surg. 2015, 100, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, J. Acidic solution irrigation as a novel approach for treating infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Med. Hypotheses 2024, 187, 111341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).