Contribution of Rare and Common APOE Variants to Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spanish Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients, Controls, and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Genetic Testing for Pathogenic Variants

2.3. APOE Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

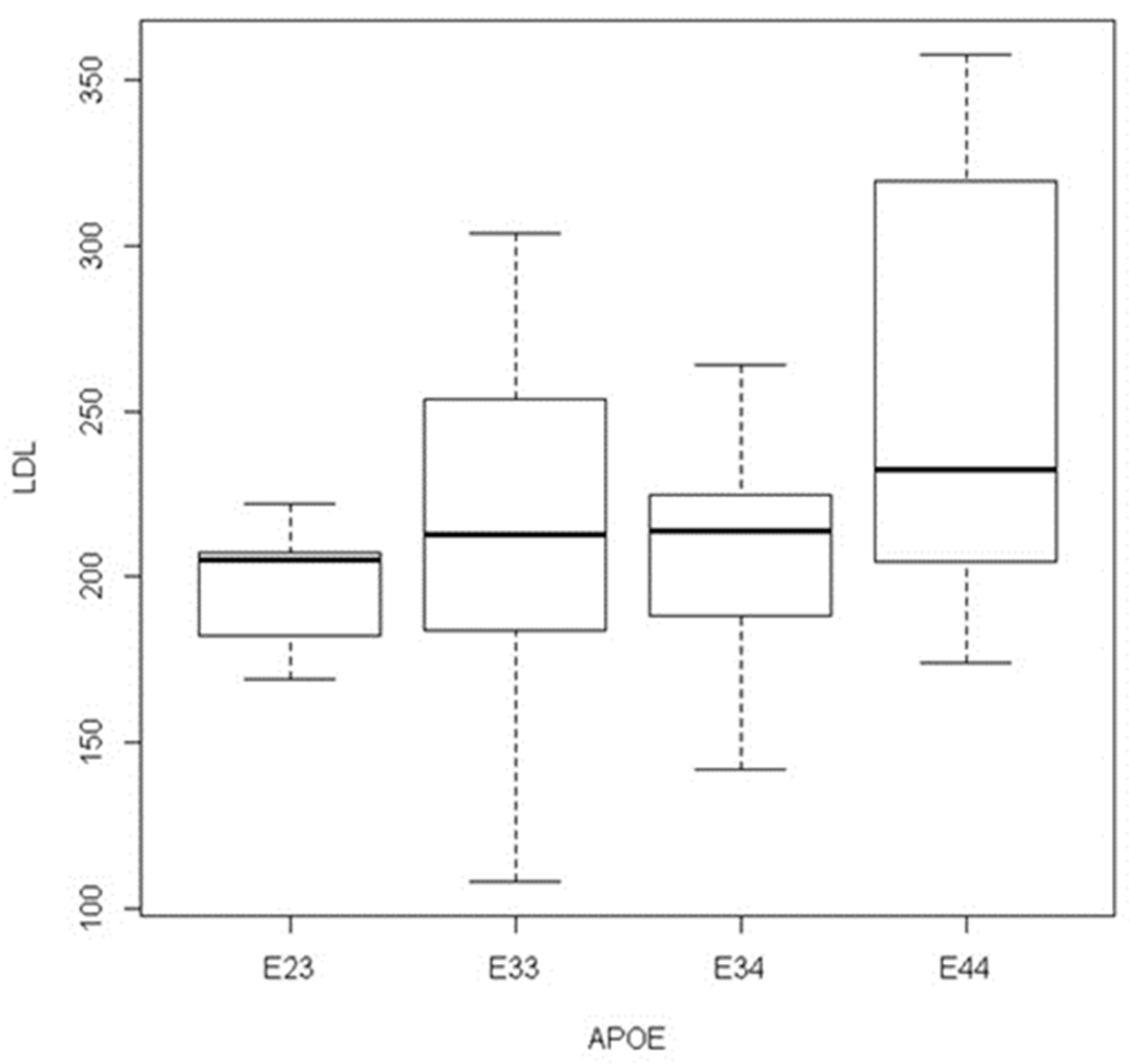

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watts, G.F.; Gidding, S.S.; Hegele, R.A.; Raal, F.J.; Sturm, A.C.; Jones, L.K.; Sarkies, M.N.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Blom, D.J.; Daccord, M.; et al. International Atherosclerosis Society guidance for implementing best practice in the care of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 845–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozik, J.; Główczyńska, R.; Grabowski, M. Genetic backgrounds and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Genet. 2024, 105, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricou, E.P.; Morgan, K.M.; Betts, M.; Sturm, A.C. Genetic Testing for Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Clinical Practice. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Moran, A.E. Genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 35, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Jiménez, M.J.; Mansilla-Rodríguez, M.E.; Gutiérrez-Cortizo, E.N. Predictors of cardiovascular risk in familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 34, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, E.; Hegele, R.A. Monogenic Versus Polygenic Forms of Hypercholesterolemia and Cardiovascular Risk: Are There Any Differences? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abifadel, M.; Boileau, C. Genetic and molecular architecture of familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 293, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandirerung, F.J. The Clinical Importance of Differentiating Monogenic Familial Hypercholesterolemia from Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’sullivan, J.W.; Raghavan, S.; Marquez-Luna, C.; Luzum, J.A.; Damrauer, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; O’donnell, C.J.; Willer, C.J.; Natarajan, P.; Cardiology, C.O.C.; et al. Polygenic Risk Scores for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, E93–E118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoye, X.; Bardel, C.; Rimbert, A.; Moulin, P.; Rollat-Farnier, P.-A.; Muntaner, M.; Marmontel, O.; Dumont, S.; Charrière, S.; Cornélis, F.; et al. A new 165-SNP low-density lipoprotein cholesterol polygenic risk score based on next generation sequencing outperforms previously published scores in routine diagnostics of familial hypercholesterolemia. Transl. Res. 2023, 255, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futema, M.; Shah, S.; A Cooper, J.; Li, K.; A Whittall, R.; Sharifi, M.; Goldberg, O.; Drogari, E.; Mollaki, V.; Wiegman, A.; et al. Refinement of variant selection for the LDL cholesterol genetic risk score in the diagnosis of the polygenic form of clinical familial hypercholesterolemia and replication in samples from 6 countries. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmastroni, E.; Gazzotti, M.; Arca, M.; Averna, M.; Pirillo, A.; Catapano, A.L.; Casula, M.; LIPIGEN Study Group. Twelve Variants Polygenic Score for Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Distribution in a Large Cohort of Patients with Clinically Diagnosed Familial Hypercholesterolemia with or Without Causative Mutations. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamiquiz-Moneo, I.; Pérez-Ruiz, M.R.; Jarauta, E.; Tejedor, M.T.; Bea, A.M.; Mateo-Gallego, R.; Pérez-Calahorra, S.; Baila-Rueda, L.; Marco-Benedí, V.; de Castro-Orós, I.; et al. Single Nucleotide Variants Associated with Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia in Families Diagnosed Clinically with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinder, M.; Cermakova, L.; Ruel, I.; Baass, A.; Paquette, M.; Wang, J.; Kennedy, B.A.; Hegele, R.A.; Genest, J.; Brunham, L.R. Influence of Polygenic Background on the Clinical Presentation of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaninger, G.; Forer, L.; Ebenbichler, C.; Dieplinger, H.; Kronenberg, F.; Zschocke, J.; Witsch-Baumgartner, M. Filling the gap: Genetic risk assessment in hypercholesterolemia using LDL-C and LPA genetic scores. Clin. Genet. 2023, 104, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, I.R.; Tada, M.T.; Oliveira, T.G.; Jannes, C.E.; Bensenor, I.; Lotufo, P.A.; Santos, R.D.; Krieger, J.E.; Pereira, A.C. Polygenic risk score for hypercholesterolemia in a Brazilian familial hypercholesterolemia cohort. Atheroscler. Plus 2022, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, A.; Villazón, F.; Suárez-Gutiérrez, L.; Gómez, J.; Martínez-Faedo, C.; Méndez-Torre, E.; Avanzas, P.; Álvarez-Velasco, R.; Cuesta-Llavona, E.; García-Lago, C.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of Patients with Genetically Confirmed Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingorani, A.D.; Gratton, J.; Finan, C.; Schmidt, A.F.; Patel, R.; Sofat, R.; Kuan, V.; Langenberg, C.; Hemingway, H.; Morris, J.K.; et al. Performance of polygenic risk scores in screening, prediction, and risk stratification: Secondary analysis of data in the Polygenic Score Catalog. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bea, A.M.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Marco-Benedi, V.; Uribe, K.B.; Galicia-Garcia, U.; Lamiquiz-Moneo, I.; Laclaustra, M.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Fernandez-Corredoira, P.; Olmos, S.; et al. Contribution of APOE Genetic Variants to Dyslipidemia. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, Y.A.; Marmontel, O.; Ferrières, J.; Paillard, F.; Yelnik, C.; Carreau, V.; Charrière, S.; Bruckert, E.; Gallo, A.; Giral, P.; et al. APOE Molecular Spectrum in a French Cohort with Primary Dyslipidemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, S.; Padilla, V.; Avila, M.L.; Gil, M.; Maestre, G.; Wang, K.; Xu, C. APOE Gene Associated with Cholesterol-Related Traits in the Hispanic Population. Genes 2021, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, Y.A.; Rabès, J.P.; Boileau, C.; Varret, M. APOE gene variants in primary dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis 2021, 328, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennet, A.M.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ye, Z.; Wensley, F.; Dahlin, A.; Ahlbom, A.; Keavney, B.; Collins, R.; Wiman, B.; de Faire, U. DaneshJ Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA 2007, 298, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva Silvino, J.P.; Jannes, C.E.; Tada, M.T.; Lima, I.R.; de Fátima Oliveira Silva, I.; Pereira, A.C.; Gomes, K.B. Cascade screening and genetic diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia in clusters of the Southeastern region from Brazil. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 9279–9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreotti, G.; Menashe, I.; Chen, J.; Chang, S.-C.; Rashid, A.; Gao, Y.-T.; Han, T.-Q.; Sakoda, L.C.; Chanock, S.; Rosenberg, P.S.; et al. Genetic determinants of serum lipid levels in Chinese subjects: A population-based study in Shanghai, China. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2009, 24, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.M.d.M.; Norde, M.M.; Fisberg, R.M.; Marchioni, D.M.L.; Rogero, M.M. Lipid metabolism genetic risk score interacts with the Brazilian Healthy Eating Index Revised and its components to influence the odds for dyslipidemia in a cross-sectional population-based survey in Brazil. Nutr. Health 2019, 25, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Rajavelu, I.; Reddy, S.; Pereira, M.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Song, Q.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, J.J.; et al. Association of Apolipoprotein E (APOE) Polymorphisms with Serological Lipid and Inflammatory Markers. Cureus 2024, 16, e60721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbo, R.M.; Scacchi, R. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele distribution in the world. Is APOE*4 a ‘thrifty’ allele? Ann. Hum. Genet. 1999, 63 Pt 4, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reales, G.; Rovaris, D.L.; Jacovas, V.C.; Hünemeier, T.; Sandoval, J.R.; Salazar-Granara, A.; Demarchi, D.A.; Tarazona-Santos, E.; Felkl, A.B.; Serafini, M.A.; et al. A tale of agriculturalists and hunter-gatherers: Exploring the thrifty genotype hypothesis in native South Americans. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 2017, 163, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, F.J.; Real, J.T.; García-García, A.B.; Puig, O.; Ordovas, J.M.; Ascaso, J.F.; Carmena, R.; Armengod, M.E. Large rearrangements of the LDL receptor gene and lipid profile in a FH Spanish population. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 31, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truty, R.; Paul, J.; Kennemer, M.; Lincoln, S.E.; Olivares, E.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Aradhya, S. Prevalence and properties of intragenic copy-number variation in Mendelian disease genes. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| FH Patients N = 431 | Controls N = 165 | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 227 (53%) | 78 (47%) |

| Women | 204 (47%) | 87 (53%) |

| Age at diagnostic range years | 18–45 | 18–60 |

| Total cholesterol mG/dL mean (range) | 345 (275–926) | 205 (78–310) |

| LDL-cholesterol mean (range) | 248 (180–750) | 132 (61–150) |

| Triglycerides | 194 (15–1132) | 97 (28–320) |

| DLCN score | ||

| 3–5 possible | 25% | - |

| 6–8 probable | 40% | - |

| >8 definite | 35% | - |

| Gene/Variant | Npatients |

|---|---|

| APOB: c.10580G>A (p.Arg3527Gln) | 2 |

| APOE: c.500_502del (p.Leu167del) | 3 |

| APOE: c.83C>T(p.Pro28leu) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.91G>T (p.Glu31Ter) | 2 |

| LDLR: c.251C>T (p.Pro84Leu) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.409G>A (p.Gly137Ser) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.464G>A (p.Cys155Tyr) | 2 |

| LDLR: c.487C>T (p.Gln163Ter) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.520G>A (p.Glu174Ter) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.530C>T (p.Ser177Leu) | 3 |

| LDLR: c.676T>C (p.Ser226Pro) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.682G>A (p.Glu228Lys) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.758G>A (p.Arg253Gln) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.682G>A (p.Glu288Lys) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.889A>C (p.Asn297His) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.916_919dupTCAG (p.Asp307Valfs*3) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1019G>A (p.Cys340Tyr) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1060G>A (p.Asp354Asn) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1176C>A (p.Cys392Ter) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1216C>T (p.Arg406Trp) | 3 |

| LDLR: c.1222G>A (p.Glu408Lys) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1246C>T (p.Arg416Trp) | 4 |

| LDLR: c.1285G>A (p.Val429Met) | 23 |

| LDLR:c.1609G>T (p.Gly537Ter) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1690A>C (p.Asn564His) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1775G>A (p.Gly592Glu) | 11 |

| LDLR: c.1796T>C (p.Leu599Ser) | 4 |

| LDLR: c.1804G>T (p.Glu602Ter) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1816G>T (p.Ala606Ser) | 2 |

| LDLR: c.1862C>T (p.Thr621Ile) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1897C>T (p.Arg633Cys) | 2 |

| LDLR:c.1898G>A (p.Arg633His) | 5 |

| LDLR:c.1966C>A (p.His656Asn) | 2 |

| LDLR: c.1973T>C (p.Leu658Pro) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.2096C>T (p.Pro699Leu) | 3 |

| LDLR: c.2099A>G (p.Asp700Gly) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.2177C>T (p.Thr726Ile) | 2 |

| LDLR: c.2397_2405del (p.Val800_Leu802del) | 1 |

| LDLR: c. 7+1G>T (IVS1+1G>T) | 7 |

| LDLR: c.1987+1 G>A (IVS13+1G>A) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1988−2 A>T (IVS13−2A>T) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.2389+4 A>G (IVS16+4A>G) | 27 |

| LDLR: c.313+2 insT (IVS3+2insT) | 5 |

| LDLR: c.1186+5 G>A (IVS8+5G>A) | 1 |

| LDLR: c.1187+1delG (IVS8−1delG) | 1 |

| LDLRAP1: c.207delC (p.Ala70ProfsTer19) HOMOZYGOUS | 1 |

| PV POS N = 139 | PV NEG N = 292 | Controls N = 165 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE at diagnostic range in years | 18–40 | 25–45 | 18–60 |

| MALE | 76 (55%) | 151 (52%) | 78 (47%) |

| FEMALE | 63 (45%) | 141 (48%) | 87 (53%) |

| LDL-C range mG/dL | 190–750 | 180–358 | 61–150 |

| LDL-C mean mG/dL | 268 | 213 | 132 |

| APOE-e2/e3/e4 | |||

| e2e2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| e2e3 | 9 (6%) | 14 (5%) | 26 (16%) |

| e2e4 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1%) |

| e3e3 | 106 (76%) | 193 (66%) | 115 (70%) |

| e3e4 | 23 (17%) | 71 (24%) | 20 (12%) |

| e4e4 | 0 | 13 (4%) | 2 (1%) |

| e3e4 + e4e4 | 23 (17%) | 84 (29%) | 22 (13%) |

| e4 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vega-Prado, L.M.; Vázquez-Coto, D.; Villazón, F.; Suárez-Gutiérrez, L.; Martínez-Faedo, C.; Menéndez-Torre, E.; Riestra, M.; González-Martínez, S.; Gutiérrez-Buey, G.; García-Lago, C.; et al. Contribution of Rare and Common APOE Variants to Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spanish Cohort. Cardiogenetics 2025, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cardiogenetics15010003

Vega-Prado LM, Vázquez-Coto D, Villazón F, Suárez-Gutiérrez L, Martínez-Faedo C, Menéndez-Torre E, Riestra M, González-Martínez S, Gutiérrez-Buey G, García-Lago C, et al. Contribution of Rare and Common APOE Variants to Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spanish Cohort. Cardiogenetics. 2025; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cardiogenetics15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleVega-Prado, Lorena M., Daniel Vázquez-Coto, Francisco Villazón, Lorena Suárez-Gutiérrez, Ceferino Martínez-Faedo, Edelmiro Menéndez-Torre, María Riestra, Silvia González-Martínez, Gala Gutiérrez-Buey, Claudia García-Lago, and et al. 2025. "Contribution of Rare and Common APOE Variants to Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spanish Cohort" Cardiogenetics 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cardiogenetics15010003

APA StyleVega-Prado, L. M., Vázquez-Coto, D., Villazón, F., Suárez-Gutiérrez, L., Martínez-Faedo, C., Menéndez-Torre, E., Riestra, M., González-Martínez, S., Gutiérrez-Buey, G., García-Lago, C., Gómez, J., Alvarez, V., Gil, H., Lorca, R., & Coto, E. (2025). Contribution of Rare and Common APOE Variants to Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spanish Cohort. Cardiogenetics, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cardiogenetics15010003