Abstract

Under the current low-carbon background, new energy vehicles are the main force in the new energy industry to reduce traffic pollution. Based on improving energy conservation and environmental protection, and taking consumers’ purchase intention (PI) of new energy vehicles (NEV) as an example, this study explores the influence mechanism of consumers’ green perceived value (GPV) and green perceived risk (GPR) on consumers’ PI of new energy vehicles. This study found that the higher the GPV, the higher the consumers’ willingness to buy NEV. Moreover, the higher the GPR, the lower the consumers’ willingness to buy NEV. Green trust plays an important role in promoting the consumption behavior of NEV. Citizens’ environmental awareness (EA) has a significant moderating effect on customers’ GPV, GPR, GT, and PI. By collecting samples from the world’s largest market, we try to provide meaningful insights for new energy vehicle companies that have entered or plan to enter the Chinese market.

1. Introduction

China’s Central Economic Work Conference proposed the implementation of the 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target for addressing climate change and strives to achieve the goals of carbon neutrality by 2060. Green development is a characterized sustainable development model, which can promote coordinated economic, social, and environmental development [1,2,3]. With the continuous improvement of science and technology, people’s quality of life has also continuously improved. The means of transportation people take tend to be diversified. People are not limited to using traditional fuel vehicles to travel, and emerging new energy vehicles have gradually occupied a certain market [4,5]. However, some problems arising from rapid economic development are unavoidable. The first is environmental problems, such as global warming, El Niño, haze weather, etc. [6]. Traditional fuel vehicles will inevitably emit harmful emissions; unfriendly waste gas is also a major source of the greenhouse effect on the urban environment. The second is the energy issue. Traditional fuel vehicles have a lower fuel economy, higher fuel consumption, gradually decreasing oil resources, and rising costs. Under the current low-carbon background, new energy vehicles are the main force in the new energy industry to reduce traffic pollution [7]. New energy vehicles are promoted globally as a green means of transportation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and are cost-effective [8,9,10]. Many countries have accelerated the transition to electric vehicles to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels, mitigate pollution, and address the energy crisis [4,11,12]. This plays a crucial role for enterprises to carry out efficient and reasonable green development strategies and form sustainable competitive advantages. Therefore, based on improving energy conservation and environmental new energy vehicles (NEV), as an example, this study explores the influence mechanism of consumers’ green perceived value (GPV) and green perceived risk (GPR) on consumers’ PI of NEV.

Globally, the vigorous development of the NEV has become the main driving force for the development of the world automobile industry, which is an inevitable choice for the country to become a powerful automobile industry. NEV use electricity rather than fuel, do not produce harmful gas emissions, can reduce traffic environmental pollution, and protect the environment. At the same time, the electric energy used by new energy vehicles is more economical than fuel, saving energy. Casals et al. (2016) found that the use of electric vehicles in European countries can reduce CO2 emissions [13]. NEVs are a step in this direction, as they not only help reduce harmful emissions, but also help combat climate change [14,15]. These new energy sources are environmentally friendly and renewable. Since new energy vehicles are relatively new technologies [16], they will also have many new features that traditional vehicles do not have. Moreover, people’s awareness of environmental protection has also continuously improved. When choosing a car, the issue of sustainability is also considered, and some consumers will choose new energy vehicles [17].

Current research mainly focuses on green purchasing behaviors in different environments, such as industrial catering services [18], bottled water recycling [19], zero-waste products [20], general green purchasing behaviors [21,22], green performance [23], sustainable food [24], and electric vehicles [25]. Several studies have investigated environmentally conscious consumer behavior in different green marketing contexts [21,26,27], including willingness to pay [28,29], the perceived value [30,31], trust [32,33], and green attitudes [34,35,36]. Other scholars have focused on the challenges of adopting electric vehicles [37,38] or from a policy perspective [39].

However, there are relatively few studies on the impact of GPR and environmental awareness on consumers’ willingness to buy green products. The perceived risk is also an important factor when considering the purchasing decision of green products because the uncertainty of green products and the information asymmetry between producers and consumers may affect consumers’ purchasing decisions. With the enhancement of people’s awareness of environmental protection and the concept of green consumption, companies should minimize the risk of green perception to improve consumers’ green trust, thereby enhancing green purchasing behavior [40,41]. Therefore, it can also be inferred that customers’ environmental awareness will enhance the impact of GPV, GPR, and green trust (GT) on consumers’ green purchase intention (GPI). This study takes new energy vehicles as an example, and looks into how consumers’ willingness to buy can be improved and how risks can be avoided so that new energy vehicles can develop powerfully and sustainably, and consumers can receive a more comfortable experience.

This study takes the NEV that have attracted much attention in recent years as the research object, trying to find out the psychological mechanism of consumers’ purchase behavior toward new energy vehicles. To our knowledge, no studies have included the five variables of GPV, GPR, GT, environmental protection awareness, and new energy vehicle’s PI into the same model for research. When faced with external stimuli, psychological changes are the first changes consumers perceive, while consumer trust is a deeper psychological change, which is the connection between consumers’ personal perception and purchasing behavior. Therefore, this study will use GPV and GPR as independent variables, GT as an intermediary variable, environmental protection awareness as a moderator variable, and the new energy vehicle purchase intention as a dependent variable by collecting samples from China. This study constructs a structural equation model and tests it, obtains relevant research, and puts forward strategies and suggestions to improve the perceived value and environmental awareness of NEV and reduce the perceived risk.

2. Conceptual Framework and Assumptions

2.1. Green Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of NEV

2.1.1. GPV

Woodruff (1997) put forward the view that consumers’ perceived value is a relative comparative concept. When consumers perceive the high value conferred by environmentally friendly products, they tend to choose these products [42]. Chen et al. (2018) defines the perceived value as the net gain that customers expect from the use of a social commerce website [43]. Wang et al. (2019) believes that consumers’ overall evaluation of products and services is based on the tradeoff between perceived benefits and perceived sacrifices [44]. Vishwakarma et al. (2020) believes that the perceived value is the result of consumers’ overall assessment of relative perceived benefits and sacrifices of products [45]. By studying consumers’ willingness to adopt electric vehicles, Kim et al. (2018) believes that the perceived value is consumers’ overall evaluation of a commodity after considering the relative weight of its benefits and risks [46]. When studying consumers’ green housing purchase intention, Zhao and Chen (2021) believe that GPV refers to the residents’ overall perception of green products based on the balance between benefits and sacrifices [47]. Zhang et al. (2020) defines GPV as the environmental protection characteristics of energy-saving products. In the context of the purchase of NEV, consumers may also pursue the environmental protection utility brought by their behavior [48].

2.1.2. Dimensions of GPV

Teng et al. (2018) defined GPV as the functional value, social value, and emotional value of green hotels when studying consumers’ behavioral willingness to stay in green hotels [49]. Soutar (2001) divided the perceived value into multiple dimensions, namely the product price, product quality, and emotional factors [50].

This study follows the improved views of Roh et al. (2022) and divides the perceived value into five dimensions [51], namely the price, emotional, social, quality, and green value. For the price value, since the NEV industry is the future trend of the auto industry and is also the key development target of the government in response to planning requirements, the government will give some preferential policies to consumers who buy NEV. There are certain car-buying benefits and some tax benefits or deductions. In addition, the long-term use of NEV can reduce fuel costs, which has a certain price value in the long run. In terms of the emotional value, from the design point of view, compared with traditional fuel vehicles, a new energy body form preference SUV or single-compartment car, where the body size is significantly larger than the same level of fuel vehicles, prefer the use of large-size wheels, four-wheel design, etc., so it can to bring customers a more comfortable experience. Meanwhile, the equipment of NEV will be more intelligent, and the riding experience will be different from traditional cars. For the social value, since NEV conform to the current trend of environmental protection, the purchase of NEV may be appreciated by the people around them, reflecting their value. For the quality value, compared with traditional vehicles, NEV will consume less energy. With the improvement of technology, the performance of NEV will be further improved. For the green value, it is the role of green products or services in saving energy, reducing pollution, and enhancing consumers’ awareness of environmental protection.

2.1.3. The Impact of GPV on Consumers’ Purchase of NEV

Sirdeshmukh and Abol (2002) optimized the relationship between GPV and PI. As the coefficient of GPV increases, consumers’ PI will also increase [52]. Jalu et al. (2023) indicated that consumers’ perceptions of GPV have indirect effects on green brand loyalty [53]. Zheng et al. (2023) demonstrated that GPV significantly positively affected green food’s PI [22]. Therefore, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

GPV has a positive impact on the PI of NEV.

2.2. Green Perceived Risk and Purchase Intention of NEV

2.2.1. GPR

Perceived risk is reflected in the fact that there are too many uncertain factors in the purchase result, such as whether the safety of NEV can be guaranteed and whether the performance is stable [54]. Harridge-March. (2006) simplified the concept and proposed that risk perception is the decision maker’s subjective expectation of loss [55]. Chen and Chang (2012) pointed out that the core of risk perception is uncertainty, but this uncertainty does not exist objectively [35]. Ai et al. (2024) thought that environmental climate change would affect human risk perception and then affect individual behavior [56]. Tao et al. (2024) believed that improving employees’ GPR can promote employees’ pro-environment behaviors [15].

2.2.2. Dimensions of GPR

Previous scholars have jointly proposed that perceived risk is a multi-faceted structure, which is mainly generated when consumers are afraid of making wrong decisions [57]. The dimensions of consumer perceived risk may vary depending on the study context [58]. Risk perception includes both financial and psychological factors. Some scholars have summarized the research on risk perception dimensions and identified a total of eight dimensions. In addition to the above five dimensions, it also includes personal risk, privacy risk, and source risk [59].

This study analyzes the risks that consumers may encounter during the purchase process and the risks that they may want to avoid. Therefore, by summarizing the research of relevant scholars, the perceived risks were divided into time, financial, security, and functional risk. In terms of time risk, since NEV are a new type of industry, their brand may not be well-known, and compared with some established brands of traditional fuel vehicles, consumers may spend more time choosing these NEV. For financial risk, some brands of NEV may be priced unreasonably or too high and the price/performance ratio of the NEV may not be high enough, as well as the fact that NEV are an emerging industry, the relevant supporting measures may not be perfect, and repairing the car may cost more money and possibly a battery replacement over time. For safety risks, NEV are emerging technologies, and some technologies may not be perfect, and there may be some safety risks. For example, the recent Tesla brake failure incident may make consumers more cautious about the purchase of NEV. In terms of functional risk, people will have higher expectations for new cars. If the expected expectations are not met, for example, the performance is not as good as expected, there may be false propaganda by the merchants that cause the product to fail to meet expectations, and the possibility that the performance defects caused by the technology of NEV may not be mature enough, which are all functional risks that may be encountered.

2.2.3. Impact of GPR on Consumers’ Purchase of NEV

Many studies have pointed out that perceived risk is an important antecedent affecting consumer behavior decision making. For example, perceived risk weakens consumer trust [60], and hinders consumers’ adoption behavior and behavioral willingness. The perceived risk theory assumes that consumers tend to minimize perceived risks rather than maximize expected returns. Perceived risks not only directly affect consumer behavioral decisions, but also offset the positive impact of perceived usefulness on consumer behavior [61]. Many studies believe that perceived risk plays a regulating role in the relationship between the perceived value and behavioral decision making. Studies have shown that in situations with a higher perceived risk, the perceived value has a stronger promoting effect on behavior. Kwok et al. (2015) argue that if consumers feel that there is a higher risk in purchasing decisions, the perceived risk will have a greater impact on their purchasing intentions. Therefore, consumers’ sense of instability, that is, their perception of risk, has a certain impact on their desire to buy [62].

Although the above scholars have researched these issues, they have not yet formed a unified view, and there is a lack of attention on how to use consumers’ perceived value and risks to react to the manufacture, sales, and promotion of NEV. Therefore, this study looks into how to improve consumers’ willingness to buy NEV based on consumers’ GPV and avoiding the risks they perceive. One of the characteristics of NEV is that they are relatively “new”. Compared with traditional fuel vehicles, their appearance, usage methods, and charging methods are very new. Furthermore, the risks brought by new energy are also greater, so consumers will pay more attention to the risks it will bring during the purchase process. Generally, the greater the perceived risk of a consumer, the lower his willingness to purchase the product. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Green perception risk has a negative impact on the PI of NEV.

2.3. The Impact of GPV on GT

Consumers can perceive the green value of products and services provided by enterprises, which plays a vital role in the development of companies and the maintenance of good relations between consumers and companies. Moreover, consumer GPV is also considered to be the most important differentiator between a company and its products and its competitors. Chen and Huang (2013) found that GPV plays an important role in strengthening GT [63]. Li et al. (2020b) proposed that consumers’ perceived value is a combination of rationality and sensibility and generated through reasonable judgment, including not only the cognition of product quality, but also the personalized perception of their preferred brands [64].

Moreover, this perceived value can affect consumers’ satisfaction with the company in the long run. If consumers are highly satisfied with the company, they will become dependent on the company and thus trust it. Based on the analysis of the current situation and characteristics of green products in this study, we can see that at the level of the emotional value, NEV pay attention to environmental protection and are beneficial to consumers’ physical and mental health; because of their social benefits, they can also bring happiness to consumers. When consumers have emotional recognition and pleasure, they can deepen their trust in products. At the level of the social value, the use of NEV can show consumers’ concern for the environment and ecology, and form a good reputation for environmental protection. At the level of the green value, when choosing NEV, consumers can satisfy their pursuit of environmental protection by purchasing NEV. In terms of the economic value, providing consumers with the value that matches their prices will gain consumers’ trust, and they will be willing to provide NEV as the environmental benefits of the car pay for it. Through the above analysis, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H3:

GPV can significantly and positively influence GT.

2.4. GPR and GT

The perceived risk theory holds that consumers are keen to reduce their perceived risk rather than increase their perceived utility when purchasing a product. Consumers have negative emotions related to the perceived risk of purchasing, which will have a negative impact on trust. Some research shows that if consumers have a higher perceived risk to a product, they will have difficulty trusting the product [65,66]. Several previous studies have shown that perceived risk has a negative impact on consumer trust [67,68]. Shiri and Jafari-Sadeghi (2023) emphasize that trust minimizes the perceived risk, thereby creating a favorable trading environment that increases the likelihood of purchase [69]. At present, with the increasingly serious environmental pollution, people are paying more attention to the protection of the environment, and more green products have entered the market. However, information asymmetry makes it more difficult for consumers to determine the actual value of a product before making a purchase, which incentivizes salespeople to make false sales. The price of green products is usually higher than that of ordinary products, and consumers find that the products have not met their expectations after purchasing the products, and some have brought losses in all aspects, which leads to higher perceived risks for consumers and doubts about whether the products on the market are really green and environmentally friendly products produced by a regular and reputable manufacturer. Based on this, the following assumption is put forward:

H4:

GPR has a negative impact on consumers’ GT.

2.5. GT and Willingness to Purchase NEV

As a category of psychology, trust is widely used in economics, education and management, and other disciplines. In the current market environment, with the increase in the green consumer demand and the enhancement of consumers’ awareness of environmental protection, many enterprises will take measures to package ordinary products into pseudo-green products to obtain higher profits. Laufer (2003) argues that GT plays an important role in consumer behavior and that products endowed with green characteristics belong to trust [62]. Schlosser et al. (2006) pointed out that trust, as the basis of the transaction market, can influence the PI behavior of consumers [52]. Chen et al. (2010) defined GT as prompting consumers to increase their beliefs and expectations for green products. In the context of green marketing, consumers’ perception of the product fit will affect GT and then consumers’ PI [60]. There is a proportional relationship between consumers’ GT and PI. Kamboj et al. (2023) argue that increased levels of GT can increase consumers’ PI, which in turn shapes their actual green purchasing behavior [70]. Viet et al. (2024) examined companies in the industrial and marine coatings sectors in Vietnam and found that GT increases PI [71].

H5:

GT has a positive impact on the PI of NEV.

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Awareness

GPV and GPR are consumers’ perceptions of their own gains or losses and are important factors that affect their willingness to purchase NEV. At the same time, environmental awareness (EA), as the environmental cognition of one’s own or others’ behavior, also affects the consumption behavior [72]. Kahn (2007) surveyed residents’ willingness to consume automobiles in six cities in California by sampling and learned from the sample data that residents who advocate environmental protection are more inclined to buy NEV [53]. Some scholars have pointed out that consumers with high EA tend to adopt green consumption behaviors [73]. Koklic et al. (2019) showed that consumers’ green environmental protection concerns can directly affect their green purchasing behavior and can also affect consumers’ green purchasing behavior through mediating effects such as their perceived behavior control [74]. Brian et al. (2010) examined whether the impact of fuel cost and vehicle registration tax on consumers is enough for them to buy NEV in replacement of gasoline vehicles [2]. Some respondents expressed concern about the current environmental pollution problem, and expressed that they would spend more money to improve the current environmental problems. Delang and Cheng (2012), based on a survey of the size of households in Hong Kong, China, found that although many people recognized the contribution of new energy vehicles to environmental protection, more people were concerned about battery pollution, and the conflict between these two ideas made them hold reservations about purchasing new energy vehicles [75]. Wei et al. (2017) proposed that the relationship between green information such as eco-labels and the green purchasing behavior is a positive correlation [76]. Cerri et al. (2018) concluded that the formation of consumers’ GPI is related to the increase in the external relevant green information, that is, positive environmental attitudes will promote the green purchase intention [57]. Kautish et al. (2019) state that EA and the recycling intention significantly moderate the impact of the perceived consumer utility and environmental protection intention on GPI [21]. However, both green consumers and current acquisition programs reduce the observed risks [77]. As consumers become more environmentally aware, they will analyze the perceived risks associated with specific purchases and be prepared to purchase sustainable products, thereby expanding the goal of purchasing environmentally friendly products [78].

Therefore, the green consumption behavior of purchasing NEV should not only be explored from the perspective of self-interest and the rational perspective of weighing pros and cons, but also from the perspective of other interests and the social perspective of protecting the environment. People’s understanding of environmental knowledge and the intensity of information publicity are important variables that affect residents’ energy conservation and environmental protection. Social–environmental problems and energy problems are becoming increasingly serious, and it is becoming more important to enhance people’s EA. Increased awareness and education can awaken and enhance people’s EA [79]. There are similarities and differences between the East and the West in raising consumers’ EA. Publicity and education are the most commonly used methods in the policies of energy conservation and environmental protection in Western countries. As the government and the public continue to call for the establishment of an environment-friendly society, consumers’ EA is gradually improving. Even if green products need to bear part of the premium expenditure, many consumers still choose to buy them. In the research process of customers’ perceived value and GPI, considering the characteristics of NEV as green products, the factors that affect consumers’ green consumption behavior are introduced to further supplement the research structure of this study. For the moderating variable of EA, this study believes that with the increasing EA of consumers, more consumers are willing to buy zero-emission or low-emission NEV. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6:

Citizens’ EA positively moderates the relationship between consumers’ GPV and their willingness to purchase NEV.

H7:

Citizens’ EA negatively moderates the relationship between consumers’ green perception risk and their willingness to purchase NEV.

H8:

Citizens’ EA positively moderates the relationship between customers’ GT and their willingness to purchase NEV.

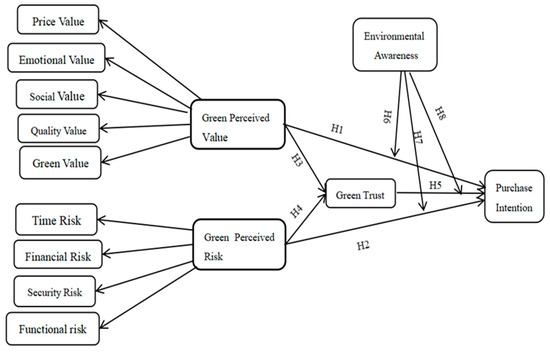

We summarize all the assumptions discussed above in Figure 1 and outline the research model. Based on SOR theory, this paper holds that environmental problems include the stimulus (S), affect consumers’ perceived state (O), and then affect consumers’ behavior (R) [80]. The arrows describe the relationships between the structures, which are subject to statistical testing.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Data Collection

The survey was distributed to Chinese residents over the age of 18 with a driver’s license, indicating that this study was designed to gain insights from individuals who are legally qualified to drive and make vehicle purchase decisions. This choice may have been made to ensure that the sample represents a segment of the population that has the autonomy to consider the adoption of NEVs. The target population was those who were considering buying a car and had no previous experience with new energy vehicles, possibly to assess people’s perceptions and intentions, regardless of past experience. The questionnaire was filled out by customers who visited the company’s showroom looking for new energy vehicles (Table A1). All variables in this study are measured using a 5-point Likert scale, and respondents answered according to their actual situation [81]. A total of 324 questionnaires were collected, 20 invalid questionnaires were deleted, and 304 valid questionnaires remained, with an effective recovery rate of 93.8%. A pilot study of 304 respondents using a structured questionnaire confirmed the surface validity and content validity of the research tool.

The valid questionnaires described and analyzed the basic situation of the respondents from the aspects of gender, age, monthly disposable income, region, occupation, education level, etc. (Table 1). The number of women surveyed was 3.5 times that of men; about 80% of those surveyed were between the ages of 18 and 25; 65.5% had more disposable income below CNY 5000. The region where they were located has the highest proportion in the Pearl River Delta region, accounting for 46%; most of the respondents were general employees of the company, accounting for 71%, followed by senior managers, accounting for 17%; the education level was mostly undergraduate, accounting for 83.2%.

Table 1.

Sample demographic.

3.2. Measurement Model

As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s score and CR scores exceed the recommended benchmark of 0.6, implying a good measure of reliability in the model [82]. Convergence validity was tested by measuring factor loadings and the extracted mean-variance (AVE). The results show that all items had factor loadings above 0.6, all AVE scores were above 0.55, and the convergence validity of our measurement model was satisfactory.

Table 2.

Reliability test.

In addition, we also performed a discriminant validity test, and the results are shown in Table 3, where the corresponding square root of AVE was significantly larger than the correlation between all the potential constructs. Thereafter, hypothesis testing could be carried out.

Table 3.

Discrimination validity.

3.3. Structural Model

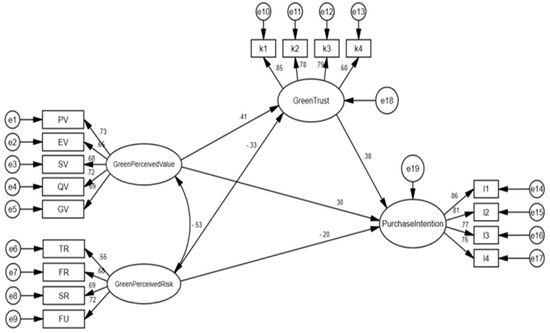

After establishing the reliability and validity of the structure, we evaluated the structural model. In this study, all indicators met the goodness-of-fit criteria, so the model can be considered to have a good fit [83]. Figure 2 and Table 4 present the normalized path coefficients for the endogenous latent variables.

Figure 2.

Results of SEM.

Table 4.

Structural equation model fitting index.

It can be seen from Figure 2 that the influence degree of the five dimensions of GPV is price value (PV) > quality value (QV) > green value (GV) > social value (SV) > emotional value (EV). The influence coefficients were 0.73, 0.72, 0.69, 0.68, and 0.66, respectively, and p < 0.001; all passed the significance test. Research shows that when consumers make new energy vehicle purchase decisions, the price value and quality value are the key driving factors, and consumers will still pay great attention to the product cost performance and the core functional attributes of products or services. The influence degree of the four dimensions of GPR is functional risk (FU) > security risk (SR) > financial risk (FR) > time risk (TR), and the influence coefficients are significant. Research shows that functional risk and safety risk are the key driving factors when consumers make purchase decisions for NEV. Consumers are concerned about the functional risk first, i.e., that the product may have defects, and then whether the product is safe.

It can be seen from Table 5 that GPV has a significant positive impact on PI (β = 0.295, p < 0.05), and hypothesis 1 is established; GPR has a significant negative impact on PI (β = −0.204, p < 0.05) and a positive influence, meaning hypothesis 2 is established; GPV has a significant positive impact on GT (β = 0.413, p < 0.05), and hypothesis 3 is established; GPR has a significant positive impact on GT (β = −0.329, p < 0.05) and a negative impact, meaning assumption 4 holds; and GT has a significant positive effect on PI (β = 0.378, p < 0.05), so hypothesis 5 holds.

Table 5.

Path analysis.

Further mediation effect indicators show (as shown in Table 6) that GT mediates the link between the GPV and PI of NEV and the link between the GPR and PI of NEV. Confidence intervals for the upper and lower bounds were calculated to check whether the indirect effect is significant. If the interval contains zero, the indirect effect is not significant. It can be seen from Table 6 that the total effect value of the GPV on PI is 0.451. The total effect value of GPR on PI is −0.328, indicating that the total effect exists. The indirect effect of the GPV on PI through GT is 0.156, indicating that the indirect effect exists; the indirect effect GPR on PI through GT is −0.124, indicating that the indirect effect exists. In the direct effect, the direct effect value of the GPV on PI is 0.295, indicating that the direct effect exists; the direct effect value of GPR on PI is −0.204, indicating the existence of the direct effect. Since the Bias-Corrected confidence intervals for all indirect effect paths do not include zero, it can be inferred that GT is a key intermediate determinant for consumers to purchase NEV.

Table 6.

Overall, direct, and indirect impacts.

3.4. Adjustment Inspection

Gender, age, monthly disposable income, region, occupation, and education level are used as control variables, GPV, GPR, and GT are used as independent variables, EA is used as a moderator variable, and new energy vehicles’ PI is used as a dependent variable in a conduct adjustment test analysis, see Table 7.

Table 7.

Moderating effect test.

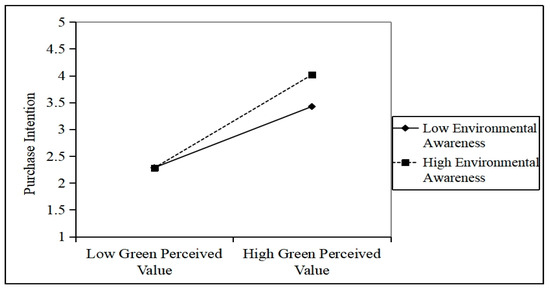

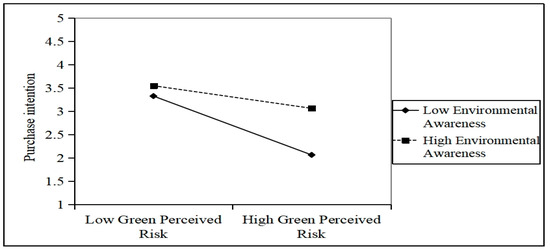

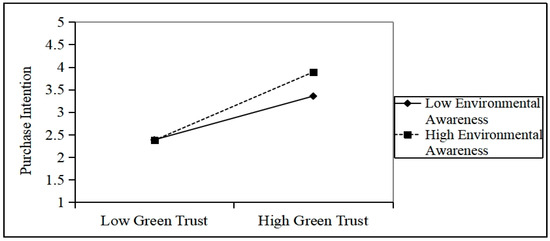

It can be obtained from Model 1 in Table 7 that EA × GPV has a significant positive effect on PI (β = 0.124, p < 0.05), indicating that EA has a significant positive moderating effect on PI in GPV. Hypothesis 6 was established. In Model 2, EA × GPR has a significant positive effect on PI (β = 0.166, p < 0.05), indicating that EA has a significant positive moderating effect on green perception risk in PI. Hypothesis 7 is established. Model 3 indicates that EA in GT has a significant positive moderating effect on PI. Hypothesis 8 is established.

To elaborate on the findings, the interaction plots are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5, respectively, with the line labeled High EA having a steeper gradient than the Low EA navigation [84]. Therefore, EA moderates the closer relationship intentions among the GPV, GPR, GT, and PI, respectively, leading to the conclusion that H6–H8 are also supported.

Figure 3.

Interaction plot of EA × GPV.

Figure 4.

Interaction plot of EA × GPR.

Figure 5.

Interaction plot of EA × GT.

4. Discussion and Managerial Implications

4.1. Discussion

First, this study attempts to explore the phenomenon and influencing factors of NEV’s purchase intention from the perspectives of consumers’ GPV, GPR, GT, and EA. Among the five driving factors of the GPV, the practical value such as price and quality values have a greater driving effect, followed by the green value; the hedonic value such as emotional and social values have less of an effect. Among the four factors of GPR, functional and safety risks are the key driving factors. Consumers pay attention to the efficacy and performance of the product first, and then worry about whether the product is safe. This finding also makes up for the lack of previous research on the driving factors of the GPV of NEV.

Second, this study found that the higher the GPV, the higher the consumers’ willingness to buy NEV. Moreover, the higher the GPR, the lower the consumers’ willingness to buy NEV [85]. GT plays an important role in promoting the consumption behavior of NEV. From an economic perspective, due to the serious information asymmetry between consumers and enterprises, GT can be used as a trusted medium to connect the two, and this GT can promote consumption willingness [86]. By receiving the green information provided by the enterprise and judging the daily pro-social activities of the enterprise, consumers will have a specific cognition of the enterprise in their hearts. The perceived value and risk in green services will enhance consumers’ trust in enterprises, which in turn enhances the green purchase tendency, that is, GT plays an intermediary role in this process. Citizens’ EA has a significant moderating effect on customers’ perceived green value, GPR, GT, and PI [75]. Due to the improvement of environmental protection awareness, consumers will also consider the benefits of the purchased products or services on the ecological environment [87].

4.2. Managerial Implications

First, companies need to adjust their marketing strategies to increase consumer trust. The price value and quality value of the GPV of NEV belong to practical values, which can promote consumers’ willingness to buy more than the hedonic value, namely the green value, emotional value, and social value. Therefore, enterprises should give priority to improving the cost performance of products. The government can increase the concessions for NEV and the purchase tax and formulate reasonable, diversified, and efficient policies to promote the optimization of the NEV industry. The most important thing for a product is its quality and performance, and enterprises need to constantly improve the technology of NEV by strengthening the safety of vehicles, prevent the occurrence of problems such as brake failure, and reduce the quality problems of NEV. Improving the battery life of NEV is also a major selling point for companies selling NEV, and it is also a concern of consumers. Furthermore, we must continue to innovate in technology, so that consumers can obtain emotional and quality satisfaction.

Second, companies need to reduce consumers’ green perception risks. Functionality and security risks are at the top of the mind for consumers. At present, domestic vehicle power batteries have shown a certain cost advantage, but consumers are still worried that the product’s poor design and poor supporting facilities have not met consumers’ expectations. Therefore, enterprises need to increase investment in research and development, solve the product safety issues that consumers are concerned about, and reduce the perceived risks of consumers. It is also necessary to jointly establish an after-sales service system suitable for new energy vehicles with insurance companies and auto repair companies to solve the problem of the use and maintenance of new energy vehicles. In addition, with the establishment of a large number of new energy vehicle charging stations, the government needs to standardize battery quality standards, establish a sound battery safety performance evaluation system, and eliminate consumers’ concerns about battery safety.

Finally, EA reflects consumers’ altruism, which was included in this study. Enterprises should focus on promoting the environmental protection attributes of NEV and vigorously advocate the idea of environmental protection to help establish people’s awareness. A very important point of NEV is environmental protection, which is in line with the development trend of the new era. Therefore, in addition to strengthening people’s ideological education, the government can also conduct some special community environmental protection activities, give some special environmental protection lectures in school classrooms, and establish incentive measures to make people more interested in the concept of environmental protection, thereby boosting the development of new energy vehicles.

Author Contributions

H.S.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Y.W.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing—review and editing, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

H.S. received funding to support this work through the Philosophy and Social Sciences Project of the Guangdong Province (No. GD22XGL49); the Education Bureau of Guangzhou Municipality (No. 202235337); Guangzhou Panyu Polytechnic (No. 2022SK03); the Guangdong Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning 2024 Youth Project (GD24YGL29); the Philosophy and Social Sciences Project of the Guangdong Province (GD24XYJ27); and the Special Project for Key Fields of Ordinary Universities in the Guangdong Province in 2024 (Serving the “Millions Project”) (2024ZDZX4110). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study does not violate any legal provisions, and such research does not require ethical approval. During the course of the study, we strictly adhered to relevant law to ensure that the rights and interests of all subjects were fully protected. All subjects signed informed consent forms and were informed of the study’s purpose, methods, and possible risks. This research does not violate any laws, regulations, or ethical norms.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude for the support and resources provided during the course of this study. Your contributions have been invaluable in shaping the insights presented in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| NEV | New Energy Vehicles |

| GPV | Green Perceived Value |

| GPR | Green Perceived Risk |

| PI | Purchase Intention |

| EA | Environmental Awareness |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

| Variable | Item | Measuring Item |

|---|---|---|

| Price Value (PV) | PV1 | I think the current pricing of new energy vehicles is reasonable |

| PV2 | I think the price of new energy vehicles is within my acceptable range | |

| PV3 | Long-term use of new energy vehicles can save me a lot of money | |

| PV4 | I think it is worth it to buy new energy cars today | |

| PV5 | I think a series of subsidy policies provided by the government for new energy vehicles will attract me to buy them | |

| Emotional Value (EV) | EV1 | I think the intelligent equipment of new energy vehicles makes me feel comfortable |

| EV2 | The energy-saving and environmental protection characteristics of new energy reduce environmental pollution and this makes me feel happy when using it | |

| EV3 | I think new energy vehicles conform to the trend of The Times, letting me feel like I am advancing with The Times | |

| EV4 | The appearance of new energy vehicles is stylish and makes me feel happy | |

| Social Value (SV) | SV1 | I think buying a new energy car makes me feel socially responsible |

| SV2 | I think buying new energy vehicles can make it easier for me to get praise and affirmation from others | |

| SV3 | I think buying new energy cars can help me build a better personal image | |

| SV4 | I think buying new energy cars can show my personal value and identity | |

| Quality Value (QV) | QV1 | The energy consumption of new energy vehicles is small, and the battery life can meet my needs |

| QV2 | New energy vehicles have stable performance and high safety when driving | |

| QV3 | The battery life of new energy vehicles is long | |

| QV4 | New energy vehicles are simple to operate | |

| QV5 | New energy vehicles have fewer breakdowns | |

| Green value (GV) | GV1 | The use of new energy vehicles will reduce environmental pollution |

| GV2 | The use of new energy vehicles will be good for social development | |

| Time Risk (TR) | TR1 | I think it will take me a lot of time to find the right brand and product information of new energy vehicles |

| TR2 | I think it will take a lot of time to fully understand the performance and use skills of new energy vehicles | |

| Financial Risk (FR) | FR1 | I am worried that the new energy vehicle-related laws and insurance systems are not sound enough to cause financial losses |

| FR2 | I will worry about the property loss caused by the imperfect charging, maintenance, and repair facilities of new energy vehicles | |

| FR3 | I think the price of new energy vehicles is too high | |

| FR4 | I am worried about the high cost of using and maintaining new energy vehicles | |

| Security Risks (SR) | SR1 | I will worry that the technology of new energy vehicles is not safe or mature enough so may cause harm to personal safety |

| SR2 | I will worry about the potential battery safety problems in new energy vehicles that cannot be found in time when they are purchased | |

| SR3 | I worry that driving new energy vehicles for a long time will do harm to my health | |

| Functional Risk (FU) | FU1 | I am worried that the performance of new energy vehicles will not meet my expectations |

| FU2 | I am worried that the performance of the car I bought is not up to the hype | |

| FU3 | I am worried that the industry technology of new energy vehicles is not mature enough and there are certain defects | |

| Green Trust (GT) | K1 | I think the environmental reputation of green food is solid |

| K2 | I think the environmental performance of green food is reliable | |

| K3 | I think the environmental claims of green food are credible | |

| K4 | I think green food promises to protect the environment | |

| Environmental Awareness (EA) | EA1 | Waste batteries can be harmful to the environment and human health |

| EA2 | I would spend more money on products that prevent environmental pollution | |

| EA3 | Poor conditions can lead to health problems | |

| EA4 | I will support organizations that support environmental issues | |

| Purchase Intention (PI) | I1 | Compared with traditional fuel cars, I will give priority to buying new energy cars |

| I2 | I would like to buy new energy vehicles in the near future | |

| I3 | I will give priority to new energy vehicles when buying my next car | |

| I4 | I will recommend to my friends and relatives to buy new energy vehicles |

References

- André, A.; Moura, P.S.; Almeida, A.D. Technical and economic assessment of the secondary use of repurposed electric vehicle batteries in the residential sector to support solar energy. Appl. Energy 2016, 181, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, C.; Seona, F.; Brian, M. Examining individuals preferences for hybrid electricand alternatively fuelled vehicles. Transp. Policy 2010, 17, 387. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Slater, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; et al. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, S.; Tomaschek, J.; Fahl, U. Perspectives of electric mobility: Total cost of ownership of electric vehicles in Germany. Transp. Pol. 2016, 50, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crescenza, C.; Angela, M.; Angela, L.; Nunziata, R. Evaluating people’s awareness about climate changes and environmental issues: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Islam, M.; Jambulingam, M.; Lim, W.; Kumar, S. Leveraging environmental corporate social responsibility to promote green purchases: The case of new energy vehicles in the era of sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ku, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y. Dual credit policy: Promoting new energy vehicles with battery recycling in acompetitive environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, L.; Zarazua de Rubens, G.; Kester, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Beyond emissions andeconomics: Rethinking the Co-benefits of electric vehicles (EVs) and vehicle-to-grid(V2G). Transp. Pol. 2018, 71, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, V.; Vaibhav, S. A review and simple meta-analysis of factors influencing adoption of electric vehicles. Transport. Res. Transp. Environ. 2020, 86, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Pyke, D.; Steenhof, P. Electric vehicles: The role and importance of standards in an emerging market. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Nelson, J.D.; Mulley, C. Electric car sharing as a service (ECSaaS) acknowledging the role of the car in the public mobility ecosystem and what it might mean for maas as eMaaS? Transp. Pol. 2022, 116, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, L.C.; Martinez-Laserna, E.; García, B.A.; Nieto, N. Sustainability analysis of the electric vehicle use in Europe for CO2 emissions reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Kumar, V.V.; Sidhpuria, M. A study on the adoption of electric vehicles in India: The mediating role of attitude. Vision. J. Bus. Perspect. 2019, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarei, P.K.; Chand, P.; Gupta, H. Barriers to the adoption of electric vehicles:evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Kumari, P. Exploring the enablers and inhibitors of electric vehicle adoption intention from sellers’perspective in India: A view of the dual-factor model. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24, e1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Cong, L.; Hui, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yu, B. Life cycle CO2 emissions for the new energy vehicles in China drawing on the reshaped survival pattern. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.H.; Ling, H.Y.; Yeow, J.; Hassan, A.; Arif, M. The infuence of green consumption cognition of consumers on behavioral intention- A case study of resturant service industry. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 7888–7895. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Tan, C.; Wu, L.; Peng, J.; Ren, R.; Chiu, C. Determinants of Intention to Purchase Bottled Water Based on Business Online Strategy in China: The Role of Perceived Risk in the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.; Hartati, N.; Gunawan, I.; Luthfi, F. Revealing consumer attitudes towards green products: The role of environmental awareness, perceived value, and media influence on zero waste products purchase intentions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1267, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Ling, S.; Cho, D. How Social Identity Affects Green Food Purchase Intention: The Serial Mediation Effect of Green Perceived Value and Psychological Distance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbeibu, S.; Emelifeonwu, J.; Senadjki, A.; Gaskin, J.; Jari, K.O. Technological turbulence and greening of team creativity, product innovation, and human resource management: Implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Tangeland, T. The role of consumers in transitions towards sustainable food consumption. The case of organic food in Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.M.; Khuman, Y.S. Electric vehicles as a means to sustainable consumption: Improving adoption and perception in India. In Socially Responsible Consumption and Marketing in Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A.; Teiga, N.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. The ecological conscious consumer behaviourbehavior: Are the activists different? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Seock, Y.K. Impacts of health and environmental consciousness on young female consumers’ attitude towards and purchase of natural beauty products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for the environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Yin, J. Antecedents of urban residents’ separate collection intentions for household solid waste their willingness to pay: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.; VoThanh, T.; Wang, J. Luxury hotels’ green practices and consumer brand identification: The roles of perceived green service innovation and perceived values. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4568–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nupur, A.; Parul, M. Green perceived value and intention to purchase sustainable apparel among Gen Z: The moderated mediation of attitudes. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 168–185. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Goudeau, C. Consumers’ beliefs, attitudes, and loyalty in purchasing organic foods. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curvelo, I.C.G.; Watanabe, E.A.d.M.; Alfinito, S. Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. Rev. Gest. 2019, 26, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceive drisk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; Lavrador, T. Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J. Envrion. Manag. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, P.; Navajas Cawood, E.; Fiorello, D. Challenges for urban transport policy after the COVID-19 pandemic: Main findings from a survey in 20 European cities. Transp. Pol. 2022, 129, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Fingerman, K. Public electric vehicle charger access disparities across race and income in California. Transp. Pol. 2021, 100, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E.; Moore, D.; Kelleher, L.; Brereton, F. Barriers to electric vehicle uptake in Ireland: Perspectives of car-dealers and policy-makers. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Yehia, E.; Nadir, A. Perceived Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Effect on Green Perceived Value and Green Attitude in Hospitality and Tourism Industry: The Mediating Role of Environmental Well-Being. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Huang, Z. The evolving policy network in sustainable transitions: The case of new energy vehicle niche in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Hsiao, K.L.; Wu, S.J. Purchase intention in social commerce: An empirical examination of perceived value and social awareness. Libr. Hi Tech 2018, 36, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Understanding consumers’ willingness to use ride-sharing services: The roles of perceived value and perceived risk. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Datta, B. Travelers’ intention to adopt virtual reality: A consumer value perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Oh, J.; Park, J.H.; Joo, C. Perceived value and adoption intention for electric vehicles in Korea: Moderating effects of environmental traits and govenmnent supports. Energy 2018, 159, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, L. Exploring Residents’ Purchase Intention of Green Housings in China: An Extended Perspective of Perceived Value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for en ergy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Lu, A.; Huang, T. Drivers of consumers’ behavioral intention toward green hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutar, S. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, A.E.; White, T.B.; Lloyd, S.M. (electronic) converting web site visitors into buyers: How web site investment increases consumer trusting beliefs and online purchase intentions. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M. Do greens drive hybrids or hummers? Environmental ideology as a determinant ofconsumer choice. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 54, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.M. The Major Dimensions of Perceived Risk. In Risk Taking and Information Handing in Consumer Behavior; Cox Donald, F., Ed.; Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1967; pp. 82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Harridge-March, S. Can the Building of Trust Consumer Perceived Risk Online. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2006, 24, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Q. Extreme weather experience and climate change risk perceptions: The roles of partisanship and climate change cause attribution. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Irniza, B.; Nor, E.; Ong, T. The mediating role of pro-environmental attitude and intention on the translation from climate change health risk perception to pro-environmental behavior. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9831. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, C. Towards green trust: The infuences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Hsu, I.C.; Lin, C.C. Website Attributes That Increase Consumer Purchase Intention: A Conjoint Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.K. Ethical consumption behavior towards eco-friendly plastic products: Implication for cleaner production. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 5, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W. Social Account ability and Corporate Green Washing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Huang, T. High speed rail passengers’ mobile ticketing adoption. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 30, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yang, P.; Zheng, S. The influence of factor brand perceived value on consumers’ repurchase intention: An empirical study mediated by brand trust. Manag. Mod. 2019, 39, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. Transport-related lifestyle and environmentally-friendly travel mode choices: A multi-level approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 107, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Madhu Kumar, R. Analysing the aspects of sustainable consumption and impact of product quality, perceived value, and trust on the green product consumption. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 73, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corritore, C.; Wiedenbeck, S.; Kracher, B. Online Trust and Health Information Websites.International. J. Technol. Hum. Interact. 2012, 8, 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Kostka, G.; Anzinger, N. Citizens’ electric vehicle purchase intentions in China: An analysis of micro-level and macro-level factors. Transp. Pol. 2019, 79, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, N.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. Corporate social responsibility and green behaviour: Towards sustainable food-business development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Matharu, M.; Gupta, M. Examining consumer purchase intention towards organic food: An empirical study. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 9, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, N.; Tran, T.; Ngo, K. Corporate social responsibility and behavioral intentions in an emerging market: The mediating roles of green brand image and green trust. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 12, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green consumption: Behavior and norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delang, C.; Cheng, W. Consumers’ attitudes towards electric cars: A case study of Hong Kong. Transp. Res. Part 2012, 17, 492–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Chiang, C.; Kou, T.; Lee, B. Toward sustainable livelihoods: Investigating the drivers of purchase behavior for green products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H.; Thurasamy, R. Predicting electric vehicles adoption: A synthesis of perceived risk, benefit and the NORM activation model. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 56, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, N.; Bajaj, P.; Batra, G. Environmentally conscious consumer behavior: An empirical study. Res. J. Commer. Behav. Sci. 2012, 2, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.V.; Sintov, N.D. You are what you drive: Environmentalist and social innovator symbolism drives electric vehicle adoption intentions. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 99, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Singh, A.; Lascu, D.N. Green smartphone purchase intentions: A conceptual framework empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D.D. Modelagem de equações estruturais com utilização do SmartPLS. Rev. Bras. De Mark. 2014, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis:conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J. Exploring the influence of anxiety, pleasure and subjective knowledge on public acceptance of fully autonomous vehicles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Wong, K.; Lau, T.; Lee, J.; Kok, Y. Study of intention to use renewable energy technology in Malaysia using TAM and TPB. Renew Energy 2024, 221, 119787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).