Educator-Informed Development of a Mental Health Literacy Course for School Staff: Classroom Well-Being Information and Strategies for Educators (Classroom WISE)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Educator Roles in Comprehensive School Mental Health Systems

1.2. Educator Perspectives on Supporting Student Mental Health

1.3. Educator Mental Health Literacy

the knowledge, skills and beliefs that help school personnel to: create conditions for effective school mental health service delivery; reduce stigma; promote positive mental health in the classroom; identify risk factors and signs of mental health and substance use problems; prevent mental health and substance use problems; help students along the pathway to care.[35] (p. 4)

1.4. Mental Health Literacy Professional Development for Educators

1.5. Development of Educator Mental Health Literacy Professional Development Curriculum in the United States

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Partners

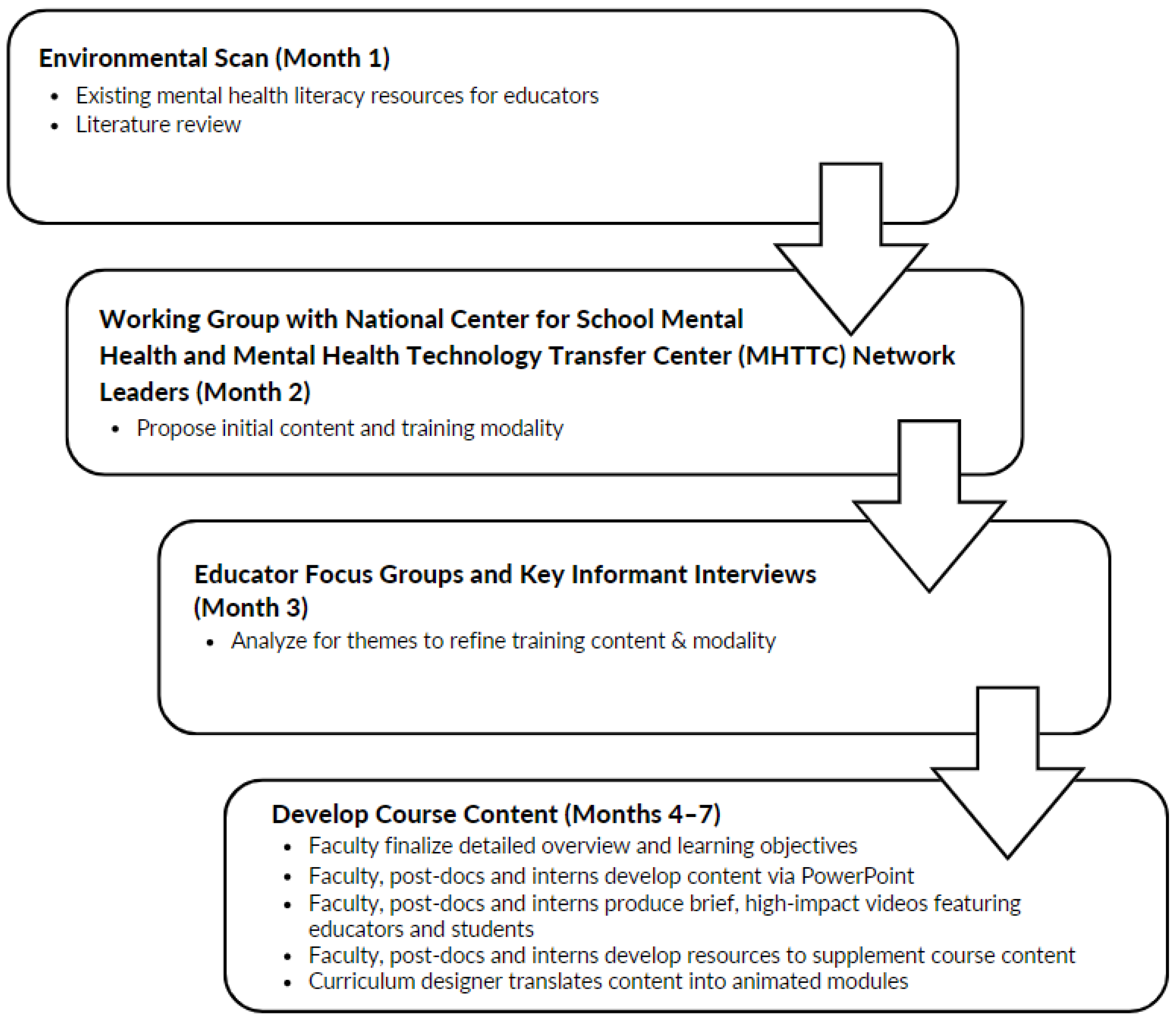

2.2. Curriculum Development Process

2.3. NCSMH and MHTTC Network Leadership Brainstorming Session

2.4. Educator Focus Groups

2.5. Key Informant Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Educator Focus Groups

3.2. Key Informant Interviews

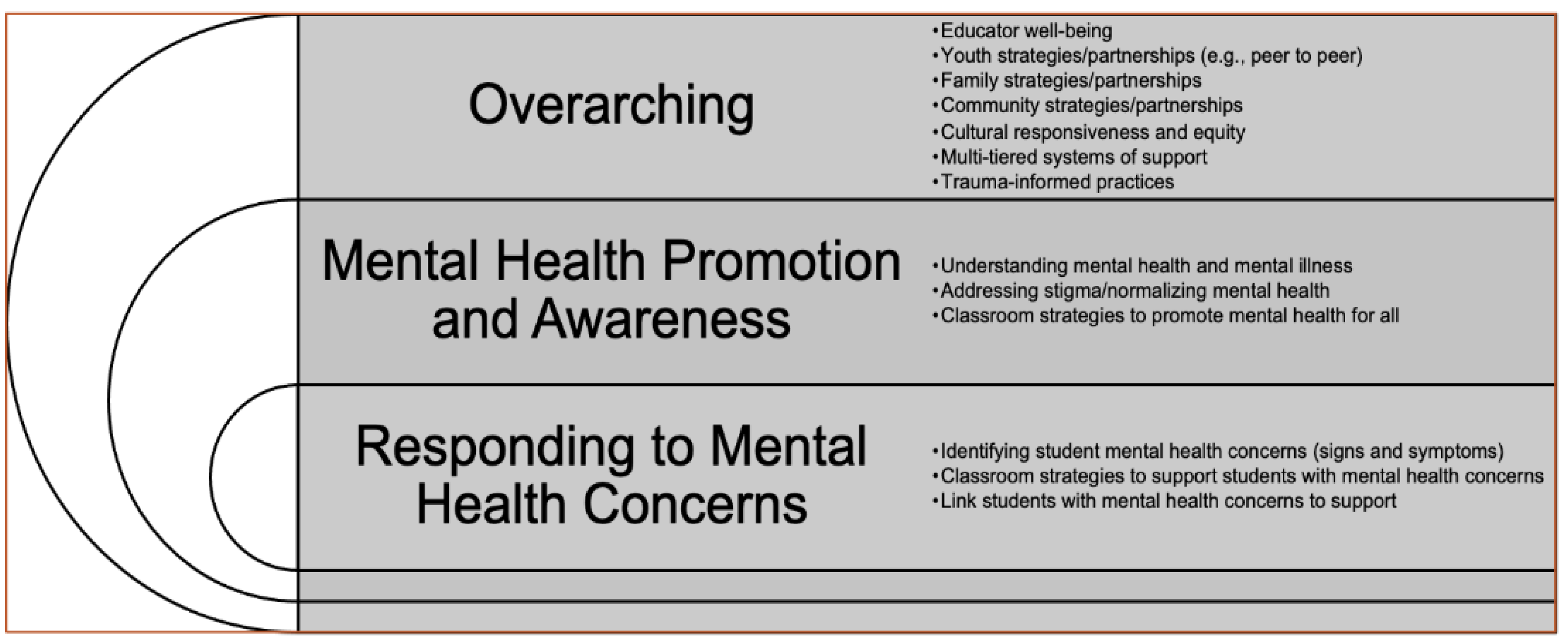

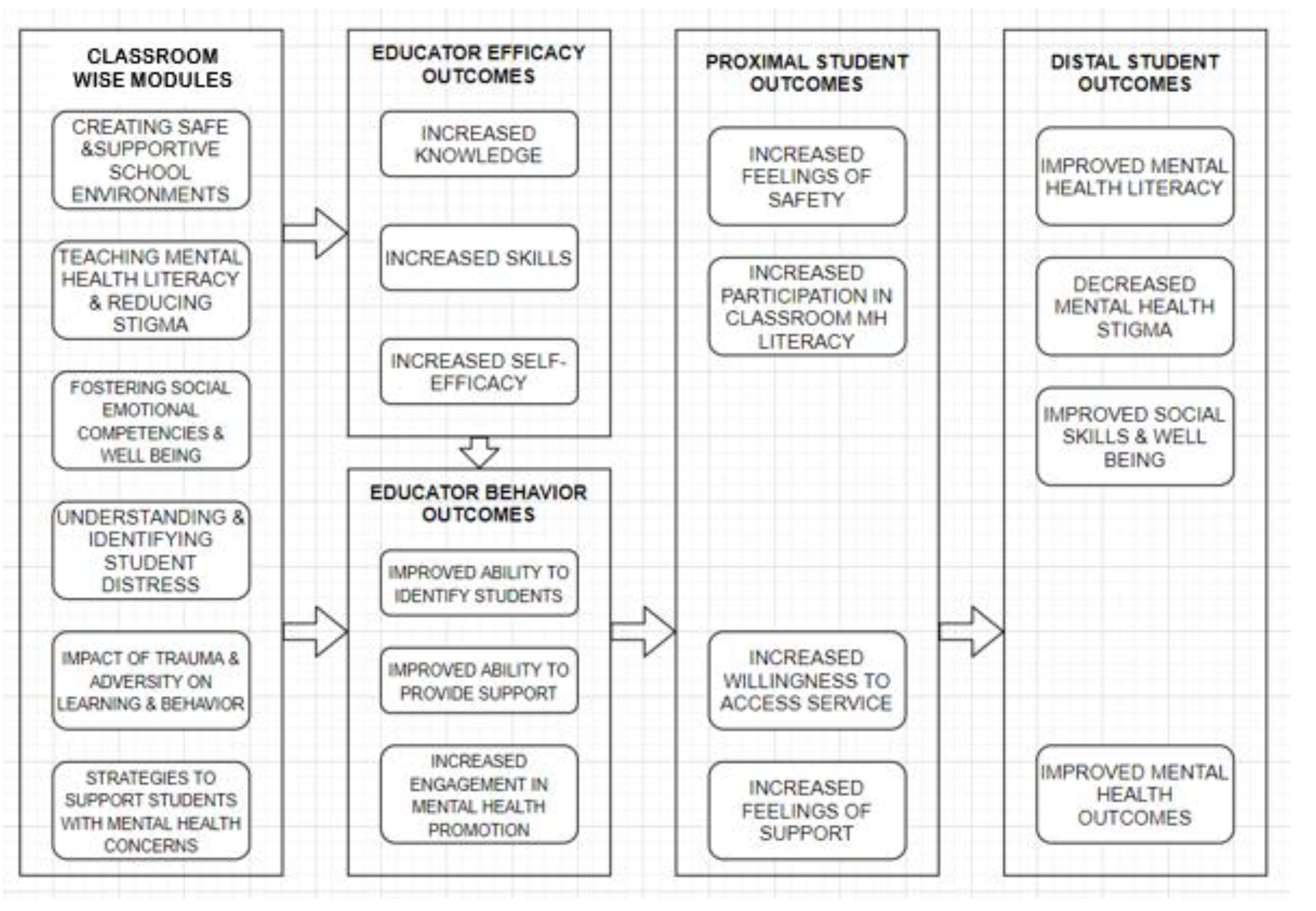

3.3. Course Structure and Content

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoover, S.; Lever, N.; Sachdev, N.; Bravo, N.; Schlitt, J.; Acosta Price, O.; Sheriff, L.; Cashman, J. Advancing Comprehensive School Mental Health: Guidance from the Field; National Center for School Mental Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 54, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Dowdy, E.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Furlong, M.J. An empirical approach to complete mental health classification in adolescents. Sch. Ment. Health 2019, 11, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J. Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34982518/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP); The Children’s Hospital Association (CHA). AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Council of Chief State School Officers; Healthy Schools Campaign; National Center for School Mental Health. Restart and Recovery: Leveraging Federal COVID Relief Funding and Medicaid to Support Student and Staff Wellbeing and Connections: Opportunities for State Education Agencies. Available online: https://learning.ccsso.org/restart-recovery-leveraging-federal-covid-relief-funding-medicaid-to-support-student-staff-wellbeing-connection (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Council of Chief State School Officers. Advancing Comprehensive School Mental Health Systems: A Guide for State Education Agencies. 2021. Available online: https://753a0706.flowpaper.com/CCSSOMentalHealthResource/#page=3 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Whitley, J.; Smith, J.D.; Vaillancourt, T. Promoting mental health literacy among educators: Critical in school-based prevention and intervention. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 28, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strein, W.; Hoagwood, K.; Cohn, A. School psychology: A public health perspective. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weist, M.D.; Lever, N.A.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Owens, J. Further advancing the field of school mental health. In Handbook of School Mental Health; Weist, M., Lever, N., Bradshaw, C., Owens, J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-0-387-73313-5. [Google Scholar]

- Splett, J.W.; Fowler, J.; Weist, M.D.; McDaniel, H.; Dvorsky, M. The critical role of school psychology in the school mental health movement. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, G.S.; Kim, J.S.; Ryan, T.N.; Kelly, M.S.; Montgomery, K.L. Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese-Germain, B.; Riel, R. Understanding Teachers’ Perspectives on Student Mental Health: Findings from a National Survey; Canadian Teachers’ Federation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-88989-399-3. [Google Scholar]

- Phillippo, K.L.; Kelly, M.S. On the fault line: A qualitative exploration of high school teachers’ involvement with student mental health issues. Sch. Ment. Health 2014, 6, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzer, K.R.; Rickwood, D.J. Teachers’ role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 8, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knightsmith, P.; Treasure, J.; Schmidt, U. Spotting and supporting eating disorders in school: Recommendations from school staff. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekornes, S. Teacher perspectives on their role and the challenges of inter-professional collaboration in mental health promotion. Sch. Ment. Health 2015, 7, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Phelps, R.; Maddison, C.; Fitzgerald, R. Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teach. Teach. 2011, 17, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, J.R.; Osterlind, S.J.; Paris, K.; Weston, K.J. Differences between novice and expert teachers’ undergraduate preparation and ratings of importance in the area of children’s mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2004, 6, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, W.M.; Stormont, M.; Herman, K.C.; Puri, R.; Goel, N. Supporting childrens’ mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothi, D.M.; Leavey, G.; Best, R. On the front line: Teachers as active observers of pupils’ mental health. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1217–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelemy, L.; Harvey, K.; Waite, P. Secondary school teachers’ experiences of supporting mental health. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2019, 14, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidger, J.; Gunnell, D.; Biddle, L.; Campbell, R.; Donovan, J. Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff’s views on supporting student emotional health and well-being. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.; McCabe, M.; Wideman-Johnston, T. Mental health issues in the schools: Are educators prepared? J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2014, 9, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, S.; Thomas, Y.; Greber, C.; Broadbridge, J.; Edwards, A.; Newton, J.; Lyons, M. Attributes of excellence in practice educators: The perspectives of Australian occupational therapy students. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2014, 61, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekornes, S. Teacher stress related to student mental health promotion: The match between perceived demands and competence to help students with mental health problems. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 61, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mælan, E.N.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Baklien, B.; Thurston, M. Helping teachers support pupils with mental health problems through inter-professional collaboration: A qualitative study of teachers and school principals. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A. Educator readiness to adopt expanded school mental health: Findings and implications for cross-systems approaches. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2011, 4, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelemy, L.; Harvey, K.; Waite, P. Supporting students’ mental health in schools: What do teachers want and need? Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2019, 24, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWalt, D.A.; Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.; Lohr, K.N.; Pignone, M.P. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourget, B.; Chenier, R. Mental Health Literacy in Canada: Phase One Report Mental Health Literacy Project; Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- School Based Mental Health and Substance Use Consortium. School Board Decision Support Tool for Mental Health Capacity Building; Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier, F.; Lalonde, G.; Venesoen, P.; Legwegoh, A.F.; Short, K.H. Educator mental health literacy to scale: From theory to practice. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2017, 10, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.K.; Ford, T.; Soneson, E.; Coon, J.T.; Humphrey, A.; Rogers, M.; Moore, D.; Jones, P.B.; Clarke, E.; Howarth, E. A systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of school-based identification of children and young people at risk of, or currently experiencing mental health difficulties. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, B.A.; Jorm, A.F. Mental Health First Aid: An international programme for early intervention. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2008, 2, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kutcher, S. Innovations in practice: ‘Go-to’ educator training on the mental health competencies of educators in the secondary school setting: A program evaluation. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 19, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, S.L.; Semchuk, J.; Lever, N.A.; Gotham, H.J.; Gonzalez, J.; Hoover, S.A. An environmental scan of mental health literacy training for educators. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2022, submitted.

- Delbecq, A.L.; Van de Ven, A.H. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1971, 7, 466–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, K.; Cervantes, P.E.; Nelson, K.L.; Seag, D.; Horwitz, S.M.; Hoagwood, K.E. Review: Structural racism, children’s mental health service systems, and recommendations for policy and practice change. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, P.L.; Skiba, R.; Arredondo, M.I.; Pollock, M. You can’t fix what you don’t look at: Acknowledging race in addressing racial discipline disparities. Urban Educ. 2017, 52, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, W.S.; Maupin, A.N.; Reyes, C.R.; Accavitti, M.; Shic, F. Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions? Yale University Child Study Center: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, S.; Chapman, S.; Spetz, J.; Brindis, C.D. Chronic childhood trauma, mental health, academic achievement, and school-based health center mental health services. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splett, J.W.; Perales, K.; Miller, E.; Hartley, S.N.; Wandersman, A.; Halliday, C.A.; Weist, M.D. Using readiness to understand implementation challenges in school mental health research. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 3101–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J.M.; Shirran, L.; Thomas, R.; Mowatt, G.; Fraser, C.; Bero, L.; Grilli, R.; Harvey, E.; Oxman, A.; O’Brien, M.A. Changing provider behavior: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med. Care 2001, 39, II2–II45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B.; Showers, B. Designing training and peer coaching: Our need for learning. In Student Achievement through Staff Development; Joyce, B., Showers, B., Eds.; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 69–94. ISBN 10-0582284090. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | White or Caucasian | 14 (93%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (7%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | No | 14 (93%) |

| Yes | 1 (7%) | |

| Gender | Female | 13 (87%) |

| Male | 2 (13%) | |

| Role | Teacher | 8 (53%) |

| School Administrator | 3 (20%) | |

| Master Teacher/Department Head | 2 (13%) | |

| School Social Worker | 1 (7%) | |

| Other | 1 (7%) | |

| Grade Level | Early Childhood | 1 (7%) |

| Elementary | 6 (40%) | |

| Middle School | 2 (13%) | |

| High School | 3 (20%) | |

| Multiple | 3 (20%) | |

| Special Education | Yes | 2 (13%) |

| No | 13 (87%) | |

| School Community | Rural | 5 (33%) |

| Suburban | 3 (20%) | |

| Urban | 4 (27%) | |

| Multiple | 3 (20%) |

| Rank | Most Highly Endorsed Responses |

|---|---|

| Most pressing educator training and resource needs related to mental health identification, referral, and supporting student mental health | |

| 1 | Recognizing warning signs of mental health issues at various ages (vs. understanding of typical development) |

| 2 | How to create a safe and welcoming classroom environment that promotes positive mental health for all kids |

| 3 | Interventions that teachers can use in the classroom for trauma |

| Suggestions to improve the content of the training | |

| 1 | Add self-regulation skills/recognizing feelings and emotions/how to develop empathy toward all students (including out of classroom settings) |

| 2 | Expand the time of the training to adequately cover content |

| 3 | Make sure cultural responsiveness is included and how mental health is viewed in different communities/cultural views |

| Recommendations for format | |

| 1 | Offer a small group or cohort format to compliment the training |

| 2 | Include question and answer component |

| 3 | Offer guidance to schools on how to best implement the training as part of a professional development day |

| Question Response |

|---|

| Most pressing educator training and resource needs related to promoting student mental health and well-being |

| Strategies |

| Stigma |

| Common mental health language |

| Positive mental health (by developmental stage) |

| Positive, healthy classroom climate |

| Wellness strategies for students and teachers (including compassion fatigue/secondary trauma) |

| Most pressing educator training and resource needs related to identification, support, and referral for student mental health challenges |

| Referral process/who to go to, including the educator’s role in the system |

| Identifying risk factors without labeling and diagnosing |

| Screening |

| Making the training more relevant and helpful for educators |

| Practical solutions |

| Concrete examples |

| Direct connections between mental health and academic success |

| Appropriate length and format for an online training for educators on student mental health |

| Short—30 min to 1 h maximum in a single module |

| Importance of personalization/ability to choose modules based on need, such as one bigger required module and multiple shorter modules that teachers can choose from |

| Make it interactive |

| Priorities for mental health topics to be covered in quick (e.g., 1 or 2 min) videos |

| Anxiety |

| Internalizing behaviors |

| Suicide prevention |

| Educator self-care |

| Challenges in educators accessing or completing an online mental health training |

| Time, including allowing teachers to start/stop modules and return later |

| Buy-in from administration |

| Tools and/or resources that should be included |

| Tools for progress monitoring |

| Handouts/visual tools with simple strategies |

| Checklists (e.g., behaviors to look for, when to follow-up and refer) |

| Module # | Module Title | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Creating safe and supportive classrooms |

|

| 2 | Teaching mental health literacy and reducing stigma |

|

| 3 | Fostering social emotional competencies and well-being |

|

| 4 | Understanding and supporting students experiencing adversity |

|

| 5 | Impact of trauma and adversity on learning and behavior |

|

| 6 | Classroom strategies to support students |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semchuk, J.C.; McCullough, S.L.; Lever, N.A.; Gotham, H.J.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Hoover, S.A. Educator-Informed Development of a Mental Health Literacy Course for School Staff: Classroom Well-Being Information and Strategies for Educators (Classroom WISE). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010035

Semchuk JC, McCullough SL, Lever NA, Gotham HJ, Gonzalez JE, Hoover SA. Educator-Informed Development of a Mental Health Literacy Course for School Staff: Classroom Well-Being Information and Strategies for Educators (Classroom WISE). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemchuk, Jaime C., Shannon L. McCullough, Nancy A. Lever, Heather J. Gotham, Jessica E. Gonzalez, and Sharon A. Hoover. 2023. "Educator-Informed Development of a Mental Health Literacy Course for School Staff: Classroom Well-Being Information and Strategies for Educators (Classroom WISE)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010035

APA StyleSemchuk, J. C., McCullough, S. L., Lever, N. A., Gotham, H. J., Gonzalez, J. E., & Hoover, S. A. (2023). Educator-Informed Development of a Mental Health Literacy Course for School Staff: Classroom Well-Being Information and Strategies for Educators (Classroom WISE). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010035