3. General Characteristics and Architecture of the PLAM Platform

The PLAM (PLovdiv Air Monitoring) platform was developed as a multi-agent system with a high degree of autonomy, adaptability, and interconnectivity between individual agents. Conceptually, it is designed as a research platform in which agents do not simply execute commands, but engage in logical interaction, knowledge exchange, and decision-making in the context of dynamic air quality data. Taking into account various factors, as well as the main air pollutants (particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, ozone), PLAM is designed to perform the following functions with optimal use of available computing resources:

Monitoring air quality based on data from various information sources.

Identification, localization, and analysis of contradictions, inconsistencies, and anomalies.

Establishing a specific “profile” of the Plovdiv area—urban air pollution has a complex structure, including natural background, regional background (formed by sources located outside the city but affecting the air quality in the city), urban background (concentrations of various pollutants caused by industrial facilities in the city itself), traffic, and other local sources. Establishing the specific profile of the city will help find more effective solutions to improve air quality.

Assisting in the establishment of secondary standards for the Plovdiv area—the secondary effect of pollution considers the impact of pollution on crops, buildings, and facilities. This is a significant issue, as the Plovdiv area is the center of vegetable production in Bulgaria.

In general, the platform can be characterized as agent-oriented, hybrid, and regional. The agents in the platform are autonomous, proactive, reactive, social, and environmentally aware software components. These properties make them extremely useful for achieving the goals we have set ourselves with the implementation of PLAM. For automated air monitoring, it is necessary to distinguish between the measuring devices and sensor networks as an environment separate from the analytical part. Autonomy and proactive behavior allow agents to self-activate when exceeding standards that users (citizens) have no way of knowing (i.e., they do not stand idly by and wait for people to tell them what to do). Agents are always active and ready to respond to changes in the environment that they can perceive. The assessment of newly received measurements of air pollutant values (i.e., changes in the agents’ environment) does not depend on specific users (who cannot know about them). The agents themselves must act depending on changes in their environment. They make decisions, invoke services, and generate results continuously and asynchronously, without the need for user intervention. Whenever an agent monitoring deviations from the norm receives a new measurement, it analyzes it based on the permissible limits and flags any discrepancies, then decides whether to generate a warning without anyone asking it to do so; it simply reacts to the event “receiving new measurements.” Agents are also reactive. As such, they can perceive and affect their environment, as well as fulfill user requests. As social components, agents can interact with each other to solve common tasks or achieve common goals, as demonstrated in the article.

The platform is hybrid because it uses two types of agents, which we have named BDI agents and ReAct (LLM-based) agents. While BDI agents focus on complex, goal-oriented behavior, reactive agents are optimized for quick response to specific events. They operate on a “stimulus-response” principle, continuously monitoring incoming messages and responding immediately upon receipt. In the system, they perform roles such as notifications and rapid processing of user requests. Agreeing with the conclusions in [

37], we also believe that ReAct agents do not have typical agent-oriented behavior, but are rather reactive components, often relying on simplified, LLM-centric architectures. However, much of the literature on LLM-based agents appropriates the terminology without committing to the core principles of the agent-oriented paradigm. There are critical discrepancies between the theory of the agent-oriented paradigm and the current implementations of ReAct architecture. On the one hand, with hybridity, we aim to reduce the effects of this discrepancy and provide a unified understanding and interpretation of the mental properties of the agents participating in the platform. On the other hand, we want to take advantage of the benefits that both types of architectures provide. Thus, in our architecture, BDI agents are primarily those that make decisions and plan the necessary actions. ReAct agents are usually more operational components that have the advantage of being relatively easy to use as an LLM reasoning engine, as well as effectively integrating and accessing various tools and services, which is essential for our platform. BDI agents have runtime support, i.e., the development environment used provides a corresponding BDI interpreter. To facilitate and unify the interaction between the two types of agents, we have developed our own BDI interpreter, which ReAct agents can use if necessary.

Most of the platforms presented in the review are global in nature, reporting on air quality over wide areas. There are good reasons for this—air pollution is transboundary. However, determining the objective air quality is difficult due to a number of local factors that affect air quality. Our goal is to build an objective “profile” of air quality in Plovdiv. In terms of the language model used, we are developing a small language model that can be fully deployed on our server configuration and trained with information specific to the Plovdiv area. Our goal is for our platform to use computing resources efficiently and sparingly. However, the platform can also be adapted for other areas (as demonstrated later in the article).

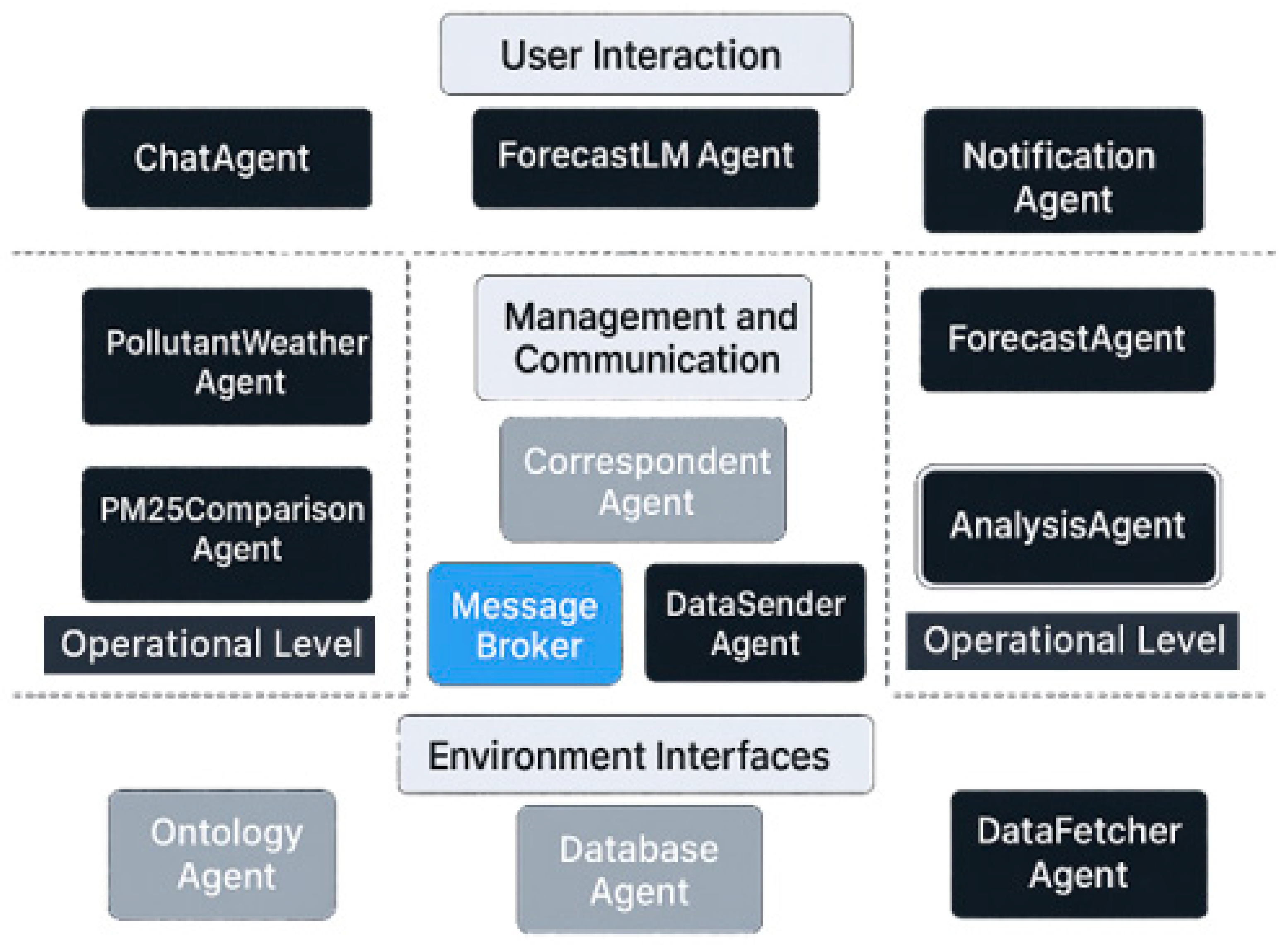

The overall architecture of the platform is shown in

Figure 1. Users can interact with the platform via a mobile device or its website. The first and important step towards complex reasoning in generative models was through a method called “chain of thought” (CoT). CoT aims for the generative model to first “think” rather than directly answering the question without any reasoning [

38]. In the PLAM platform, CoT is developed as a hybrid structure incorporating the BDI and ReAct (or AI) agents presented above. We hope that combining the positive aspects of both architectures will have a synergistic effect.

A characteristic feature of agents is that they operate in an environment with which they can interact. In PLAM, we distinguish between structured and unstructured environments. The structured environment includes a specialized ontology (ontology is presented in more detail in our previous article for this journal [

1]), storing basic knowledge for air monitoring, and a relational database in which data from university sensor network measurements are recorded. The unstructured environment consists of external information sources that publish air measurement data from various interested institutions.

The lowest level of the platform is formed by IoT nodes. For this study, an integrated environmental monitoring system comprising three proprietary sensor networks located in various spatial and functional zones was employed to cover a wide range of atmospheric and microclimatic conditions. The networks are centralized in town area of Plovdiv, at a Research Institute of Vegetable Crops ‘Maritsa’ (RIVC), located on the outskirts of the city as well as at a Plant Genetic Resources Institute (PGRI), which is approximately 20 km from Plovdiv. The sensor infrastructure at PGRI comprises a sensor set consisting of about 7–8 sensors designed for outdoor condition monitoring. At RIVC a total of eight sensor clusters has been installed. Each sensor cluster encompasses between 5 and 10 different sensors measuring a variety of environmental parameters, which are relevant for the growth and development of vegetable crops. This configuration provides high spatial and parametric resolution of data in an agroecological context.

The urban sensor network in Plovdiv consists of 7 sensor groups, each equipped with 8 sensors covering basic atmospheric and ecological parameters. Additionally, fixed remote measuring systems are installed in the urban area, including a spectral instrument type DOAS (Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy) and a LIDAR system for obtaining vertical atmospheric aerosol profiles. These tools expand the analysis capabilities through the application of remote sensing methods. Regarding data collection methods, the majority of measurements are done by in situ sensors that provide continuous and locally representative data. DOAS and LIDAR systems are classified as remote sensing methods and contribute to gathering integral and profile information of the composition and structure of the atmosphere. Data transmission from all sensor networks is performed via the POST mechanism, which ensures reliable and standardized communication between measurement devices and the central data storage and processing system. It is implemented on standard TCP/IP protocols. This automated transmission supports structured data exchange formats (e.g., JSON or XML), which ensures compatibility, traceability and allows for subsequent processing and archiving.

The combination of various types of sensors, spatially distributed networks, and a hybrid measurement approach (in situ and remote) provides a solid basis for complex environmental analysis and facilitates scientific research in the fields of atmospheric physics, agroecology, and natural resource management.

The three sensor networks consist of cheap PM2.5/PM10 nodes, covering a 35 km2 area in the vicinity of Plovdiv. Data is collected at 5 min intervals and transmitted every 30 min through secure channels to the central platform via MQTT. The data are processed at a speed of 1.2 million records per month with an end-to-end latency of less than 4 s. The data received from the three sensor networks is stored in a single relational database.

4. PLAM-CoT

The PLAM-CoT architecture combines deliberative (implemented by JADEX environment [

39] and given on a gray background in the diagram) and reactive agents (implemented by Atomic Agents [

40] and LangChain [

41] and given on a black background in the diagram) into a harmonious system. The BDIAgent class provides an environment for complex planning and long-term goal execution, while the ReactiveAgent class ensures immediate response to significant events. This hybrid design allows the system to address strategic tasks and operational requirements simultaneously. The CoT architecture is built on the following four levels (

Figure 2): interaction with users, management and coordination, operational level, interfaces with the environment.

Management and Communication Level. The agent-based paradigm lies at the foundation of the architecture, where each module performs specific responsibilities within the overall platform. The agents operate in an environment managed by a Message Broker, which serves as a central communication intermediary coordinating the flow of messages, requests, and events. MessageBroker is the core of the communication infrastructure. It facilitates asynchronous message exchange among the agents in the system, ensuring independence and eliminating dependencies between individual components. This makes the system easy to extend, as new agents can be added without risk of disrupting existing dependencies. The applied model resembles “publish–subscribe” architectures used in large distributed systems but is strongly adapted to the cognitive environment in which the agents operate, focusing on logical interactions among them. Such a structure facilitates distributed processing and the easy addition of new agents without requiring changes to the core logic. This modularity is typical of cognitive architectures of the BDI (Belief–Desire–Intention) type, where the system implements a reasoning process for decision-making based on beliefs, desires, and intentions. The DataSenderAgent serves as a communication bridge, sending data to the deliberative CorrespondentAgent. The agent has a BDI function, with the primary task of formatting internal knowledge—represented as data within ACL messages—and sending it to the CorrespondentAgent. This ensures the possibility of sharing data with the deliberative part of the platform. The CorrespondentAgent, on the other hand, acts as the facilitator and coordinator for the platform’s reasoning processes. It is the point of contact for external queries and orchestrates the fulfillment of those queries by delegating to the appropriate agents. The CorrespondentAgent’s beliefs include the current set of pending user requests and a map of partial results received from other agents. Its desires/goals typically center on providing a comprehensive answer about the air quality status for a given city and pollutant, which often requires combining information from multiple knowledge sources. The CorrespondentAgent’s plans are designed to achieve these goals: upon receiving a request it simultaneously dispatches sub-requests to the OntologyAgent and DatabaseAgent. This parallel invocation is a key advantage of the agent approach—by fetching normative data and live sensor data concurrently, the overall response is faster. The CorrespondentAgent then waits for both replies (or error notifications) to arrive, aggregates the results and sends the combined information back to the requester. If one of the sub-results fails, the CorrespondentAgent can decide how to handle it—for instance, it may still return the available part (with a warning that one component is missing), thus exhibiting flexibility in partial fulfillment. Internally, this agent can be seen as executing a simple workflow. It logs interactions in its belief base so that responses can be correlated with requests. The CorrespondentAgent essentially abstracts the rest of the multi-agent system as a unified “service” to outside clients, hiding the complexity of coordination behind a single interface.

The platform is implemented as an autonomous, continuously operating multi-agent system with an asynchronous MessageBroker architecture, designed for long-term monitoring and analysis of environmental data. To assess its practical applicability and engineering reliability, a systematic measurement of key performance indicators was conducted under clearly defined conditions and an experimental protocol.

End-to-end latency is defined as the time interval between the moment new data enters the system (successful retrieval from a sensor or external API and registration in the database) and the moment the processing result becomes available to the end user via a dashboard or notification. This includes coordination between agents through the MessageBroker, internal logical processing, and, where applicable, a single LLM request. All measurements were performed on a standard server configuration with 4 CPU cores, 8 GB RAM, and stable network connectivity, using a fixed software version and identical agent settings.

With a standard monitoring interval of 30 min and LLM analysis enabled, the average end-to-end latency is 2.8 s, while the 95th percentile (P95) of the latency distribution remains below 4.1 s. The use of the P95 percentile allows evaluation of worst-case yet still typical scenarios and is standard practice in real-time system assessment. In configurations without LLM analysis, the average latency is below 1.2 s, indicating that the primary contribution to delay comes from the external LLM service rather than from the MessageBroker layer or agent coordination.

LLM analysis is implemented through a single request with a constrained and fixed prompt and a maximum length of 1500 tokens, ensuring a balance between analytical depth and predictable response time. Caching of immutable context components (norms, structural instructions) is employed, further reducing latency and variability. This makes it possible to achieve an average end-to-end latency below 3 s even with the LLM component enabled.

The throughput of the MessageBroker was measured using synthetic load with concurrently active agents. In a configuration with 20 agents, each generating an average of 5 messages per second, the system stably processes over 100 messages per second without loss or degradation of latency. These values significantly exceed realistic operational conditions, providing sufficient headroom for peak loads. Under simulated short-term spikes of up to 500 messages per second, a temporary increase in queue sizes is observed, but without system failure or loss of functionality. Latency increases smoothly, confirming the effectiveness of the back-pressure mechanism.

The limitation of queues to 100 messages per agent is an intentional design choice. When a queue is full, additional messages are deliberately dropped, with the event logged and interpreted by the sending agent as an overload signal. This prevents uncontrolled message accumulation and cascading system degradation, treating message loss as controlled and observable behavior rather than as a hidden failure.

System reliability was evaluated through continuous operation for over 30 days. A critical failure is defined as a state in which the MessageBroker or central coordination ceases to function, and data processing becomes impossible. No such failures were recorded during the observation period. Individual agents may temporarily fail due to external causes (e.g., API unavailability), but this does not affect the rest of the system. The recovery time after an agent error is defined as the interval until the next successful monitoring cycle, without requiring a platform restart.

The results were obtained through repeated trials under identical conditions, analyzing averages and distributions rather than single measurements. This ensures the robustness of the observed metrics. The selected test parameters, such as a 30 min monitoring interval and 20 agents, reflect a scenario for a medium-sized city and represent a balanced compromise between operational frequency and resource efficiency.

Operational Level. The next processing level is represented by the PM25ComparisonAgent and AnalysisAgent, which implement comparative and analytical functions in the system. Their operation is based on a cognitive approach: they not only compute statistics but also interpret results, extract patterns from the data, and formulate hypotheses, interacting with large language models (LLMs) for this purpose. This gives the system a better understanding of the meaning of the data and allows it to perform more complex analyses of environmental information. The agents function as independent experts who autonomously manage their actions by maintaining their own internal state and activation criteria. They determine for themselves when to act, based on time intervals and available data. The PM25ComparisonAgent and AnalysisAgent respond immediately to environmental changes, not simply waiting for events but proactively checking for them and planning their activities in advance. The agents work closely together, with the PM25ComparisonAgent providing data comparisons that the AnalysisAgent uses for deeper analysis performed by LLM. The PollutantWeatherAgent and NotificationAgent represent reactive units within the hybrid PLAM architecture. The PollutantWeatherAgent acts as a reactive analytical agent functioning as an interpreter of sensor data. It receives raw CSV data from external sources—specifically AQICN and IQAir, which relate solely to atmospheric conditions for each individual day—and performs a full processing cycle, from validation and parsing of the data to calculating metrics and statistical dependencies. At the core of its operation lies the concept of empirical cognition: the agent does not generate its own intentions but reacts to changes in input data, which then activate higher-order cognitive agents in the system. An important aspect of the PollutantWeatherAgent’s work is the use of an LLM. After processing all data, the agent passes it to the language model, which identifies causal relationships between meteorological factors and air pollution. The agent thus acts as a mediator between the empirical and cognitive layers of the architecture. The ForecastAgent extracts data from the AQICN and IQAir websites at a preset interval (default 30 min) and generates an alert when PM2.5 or PM10 levels are elevated. The agent integrates machine learning approaches (Random Forest Regressor), temporal analysis and data visualization, as well as automatic email notifications.

Environment Interface Level. The DataFetcherAgent provides the incoming data stream by combining inputs from different sources—on the one hand, scraping mechanisms, and on the other, external API services. The agent serves as the “sensory input” of the system, ensuring the continuous updating of empirical data. The agent independently decides when to retrieve data without human intervention, managing its goals and priorities and automatically recovering from errors so that it can continue functioning. Its reactivity and proactivity appear in its rapid response when current data is missing, by initiating preliminary actions to obtain such data, as well as planning and performing extraordinary actions when urgent information is required. The DataFetcherAgent communicates with the rest of the agents in the system using ACL messages. An example of such communication is the “inform” message it sends to the PM25ComparisonAgent, which then uses the received data to compare pollutant measurements for PM2.5 from different sources.

To ensure reliable storage and access to information from measurements, forecasts, comparisons, and analytical results, PLAM uses a database. It functions as the system’s memory, on which agents build their beliefs and from which they draw information for decision-making. Through the creation of aggregation functions and statistical extraction, the system achieves a well-structured information architecture. The DatabaseAgent serves as the bridge to the live and historical observation data stored in the relational database. Its beliefs include the endpoint or connection parameters for the data API and placeholders for query parameters like city and pollutant. The DatabaseAgent’s primary goal is to fetch the latest measurement for a given pollutant in a given city. Upon receiving a request, the DatabaseAgent formulates an HTTP query to the data service and sends it out. Its intention then is to parse the JSON response (or any returned data structure), extract the relevant fields (e.g., value and timestamp), and deliver that as an ACL message back to the requester. If the query yields no data (e.g., the database has no recent entry for that pollutant/city) or if a timeout/error occurs, the DatabaseAgent replies with a failure message to indicate the observation could not be obtained. Under normal operation, this agent effectively wraps the database with an agent interface, translating a high-level question into the necessary data operations. This design allows us to change the underlying data source or API without affecting other agents—only the DatabaseAgent’s implementation would need updating if, say, we moved from a local DB to a cloud data warehouse. Additionally, the DatabaseAgent could perform on-the-fly data post-processing: for instance, if the request was for an average over a period, it could compute that after retrieving raw data. In our current scenario, it focuses on current values to complement the OntologyAgent’s normative output.

The OntologyAgent encapsulates access to the domain knowledge and regulatory rules encoded in the system’s OWL ontology (presented in the previous article [

1]. Its beliefs include the loaded ontology model (an in-memory representation of the OWL file) and relevant identifiers or mappings for classes/properties representing cities, pollutants, and limit values. The ontology itself contains individuals for each city and pollutant, with data properties defining threshold values. The OntologyAgent’s desire is to provide the “official” permissible level (or other semantic info) for any pollutant–city combination requested. When it receives a request (from CorrespondentAgent) specifying a city and pollutant, its intention/plan is to query the ontology via a reasoner or OWL API for the corresponding limit value. If the ontology contains the information, the agent retrieves it and formats it into a reply message. The OntologyAgent demonstrates how incorporating a semantic component allows the platform to reason about meaning rather than just data.

User Interaction Level. The NotificationAgent, in turn, is a reactive communication agent focused on synchronization among the system’s other agents. Beyond functioning as a notification component, it also acts as a “social mediator” within the agency, receiving, interpreting, and forwarding messages between agents. It monitors the proper completion of each process and informs the user interface accordingly. Its key characteristic is rapid response to events, ensuring that every system state is communicated clearly and promptly. Through a continuous cycle of monitoring and event checking, the NotificationAgent ensures the connection between the system and the user. The ChatAgent and ForecastLLMAgent extend the system toward interactivity, enabling communication with the user through natural language. They function as cognitive mediators that contextualize the system’s knowledge and present it to the user in an accessible way. The agents act based on user requests, demonstrating high sensitivity to external stimuli and an ability for immediate response. Although highly reactive, the ChatAgent does not merely wait for queries—it proactively gathers information with the ultimate goal of delivering more accurate responses to the user. The ForecastLLMAgent generates its forecasts using predefined templates and evaluation norms. Social capability is strongly expressed in both agents: aside from communicating with the user, they interact actively with other components of the system through ACL messages to obtain data, which they then structure into a clear and comprehensible form for the client.

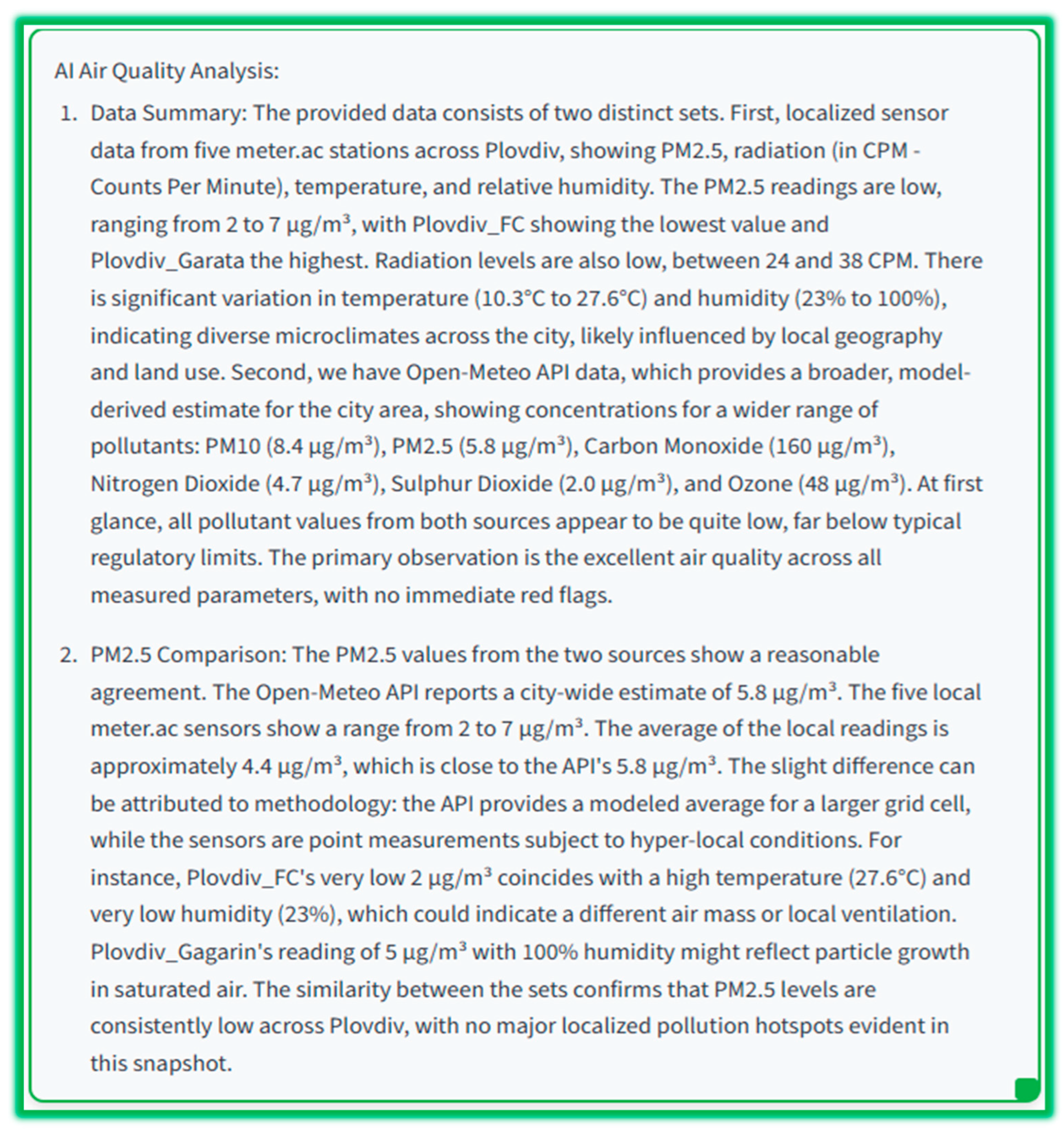

In the PLAM platform, LLM-based agents are used as an interpretative and explanatory analytical layer rather than as a primary source of numerical estimates or as an autonomous predictive model. All quantitative data, including atmospheric pollutant concentrations, meteorological parameters, and background radiation levels, are obtained exclusively from deterministic sources—the local sensor network and external data providers—and are supplied to the language model in a structured, unaltered, and semantically annotated form. The LLM does not perform statistical aggregation, interpolation, or extrapolation of raw measurements; instead, it solely synthesizes a textual explanation of already available numerical values and their interpretation with respect to clearly defined normative reference thresholds.

The analytical process is fully specified by a fixed command, which serves as a formalized analytical protocol. This command is immutable within the system configuration. The command used has the following structure

Figure 3.

The prompt explicitly prohibits free generation, the introduction of external knowledge, and hidden assumptions, thereby minimizing the risk of hallucinations and conceptual drift. The formal reasoning sequence is predefined, which enables comparability of results over time and across different experimental configurations.

To ensure result stability, the DeepSeek language model is used with fixed parameters that are part of the experimental protocol. During all analyses, the generation temperature is set to 0.1, which practically eliminates stochastic variability in the output. The top-p parameter is fixed at 0.9, preserving linguistic fluency without allowing semantic deviation. The maximum response length is limited to a predefined 1500 tokens, sufficient for a complete analytical report but insufficient for uncontrolled expansion. A fixed version of the model (a specific checkpoint) is used, ensuring that results are not affected by future updates to the architecture or training process.

With respect to reliability and error management, the platform applies a multi-layer control mechanism. At the input level, all data are validated for presence, type, and physical plausibility, with missing or inconsistent values explicitly marked and passed to the LLM as such. Within the analysis, the model is instructed to treat these cases as sources of uncertainty rather than as opportunities for interpolation. At the output level, LLM results are treated as interpretative text rather than machine-executable decisions. They are stored together with the input context, timestamps, and the model settings used, ensuring full traceability and auditability.

Potential hallucinations are addressed through a combination of preventive and reactive mechanisms. Preventively, the prompt and parameter settings strongly constrain the model’s generative freedom. Reactively, the system enables cross-checking between the textual analysis and deterministic calculations of normative states performed outside the LLM. In the event of discrepancies between numerical evaluations and textual interpretation, the result is flagged for additional review and is not used for automated notifications or visualizations without human intervention.

The role of LLM-based analysis is analogous to that of an expert interpreter who formalizes and communicates the outputs of the measurement and analytical infrastructure without replacing the primary data. This positioning allows LLM-dependent results to be methodologically defensible.

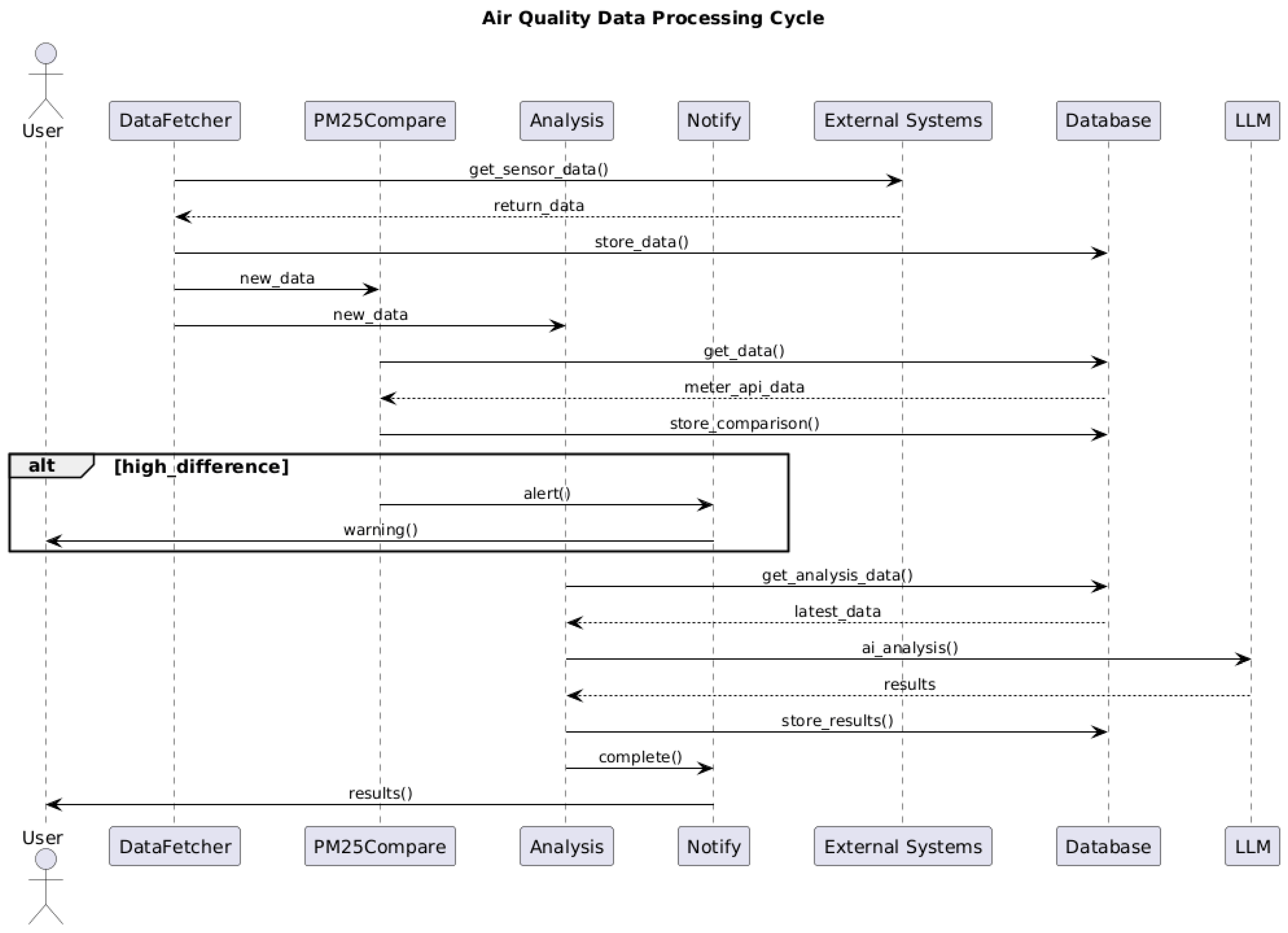

We demonstrate the principal interaction between some of the agents in one session with two sequencing diagrams. In the first Sequence diagram (

Figure 4), the autonomous data-processing cycle and the independent operation of the multi-agent system are presented. The DataFetcher agent retrieves data and stores it in the database. The system then simultaneously notifies the PM25ComparisonAgent and the AnalysisAgent about the available data. The PM25ComparisonAgent compares PM

2.5 values from different sources and generates alerts when critical deviations occur. The AnalysisAgent extracts enriched data and sends it to LLM for analysis using a chain-of-thought methodology. The results are presented to the user and stored in the database. The cycle demonstrates full autonomy—each stage triggers the next without human involvement. The system integrates heterogeneous data sources, applies specialized algorithms, and uses artificial intelligence to perform continuous monitoring.

The second sequence diagram (

Figure 5) illustrates the chat function using contextual memory, which demonstrates how the ChatAgent coordinates information from multiple sources to produce accurate and complete responses. When a user request is received, the agent simultaneously retrieves current sensor data through the DataFetcherAgent, comparative analyses from the PM25ComparisonAgent, and semantic interpretations from the AnalysisAgent. After processing all contextual elements, the system generates an enriched query for the LLM. The personalized response produced by the LLM is a synthesis of multidimensional data, transforming a simple user request into a dialogue with full awareness of the current air conditions and pollution levels. The presented mechanism implements contextual intelligence by integrating dispersed information into coherent communication.

The hybrid architecture of the PLAM platform implements a clearly delineated yet tightly coordinated model of cooperation between two distinct agent construction paradigms: the classical BDI agent (Belief–Desire–Intention) and an LLM-based ReAct agent. This cooperation is organized to leverage the strengths of each paradigm while simultaneously minimizing their limitations.

The BDI agent performs the role of a central cognitive coordinator and is responsible for the long-term, goal-oriented behavior of the system. It maintains an explicit representation of the system’s internal state through beliefs, which are updated upon the arrival of new data or events. Based on these beliefs, the agent activates desires, which reflect both periodic tasks (e.g., regular analyses) and externally initiated requirements (e.g., manually triggered analyses). The selection of intentions and the creation of plans are carried out through a priority-based evaluation of active desires, ensuring predictability and enabling controlled behavior.

The LLM-based ReAct agent, in contrast, is designed as a reactive component with minimal internal state and no long-term planning. Its function is the rapid interpretation of incoming requests, the performance of contextual analysis via a language model, and the generation of immediate responses, predictions, and explanations oriented toward the end user. The ReAct agent does not make autonomous strategic decisions and does not manage the global behavior of the system; instead, it acts as a specialized cognitive “coprocessor” activated on demand.

Cooperation between the two types of agents is implemented entirely through asynchronous, message-based communication implemented via a central broker.

An important architectural decision is that the LLM agent does not directly modify the beliefs, desires, or intentions of the BDI agent. The results of the LLM analysis are treated as informational messages that may be used by the BDI layer but do not bypass its evaluation and planning mechanism. In this case, the LLM agent generates and sends an inform performative according to the ACL specification, which the BDI agent receives and processes. In this way uncontrolled influence of the language model on the system logic and significantly limits the risk of hallucinations or logically inconsistent actions is prevented.

The BDI agent guarantees consistency, robustness, and control over the lifecycle of the analysis, while the ReAct agent optimizes latency and interaction quality by providing high-quality responses. This asymmetry reflects the philosophy of the platform: the language model is a powerful analytical tool, but not an autonomous decision-making entity.

The hybrid cooperation model in PLAM can be formalized as a hierarchical cognitive architecture in which the BDI agent acts rationally and embodies the system’s intentions, while the LLM-based ReAct agent functions as a highly efficient, context-sensitive analyzer and human-facing interface.

5. Demonstration Example

We would like to demonstrate the use of the platform in real conditions with one example. One of the first tasks that the platform has to solve is to compare data obtained from different sources for greater objectivity. It turns out that this is not a trivial task for the Plovdiv region. In most cases, analyses are based on partial data, and it was intuitively assumed that there were discrepancies in the measurements of the various institutions involved. The use of the platform shows that it can contribute to the objectivity of information by using the full set of measurements and preparing an objective comparative analysis. For example, in the first version of the platform [

1], we took the data from our university sensor network as a reference (i.e., we compared the deviations in other systems against it). However, subsequent research and analysis with the platform showed that this (somewhat intuitive) understanding was wrong. So, in the current version, we changed our decision and now accept as reference the data obtained from the Open-Meteo, IQAir, and AQICN systems.

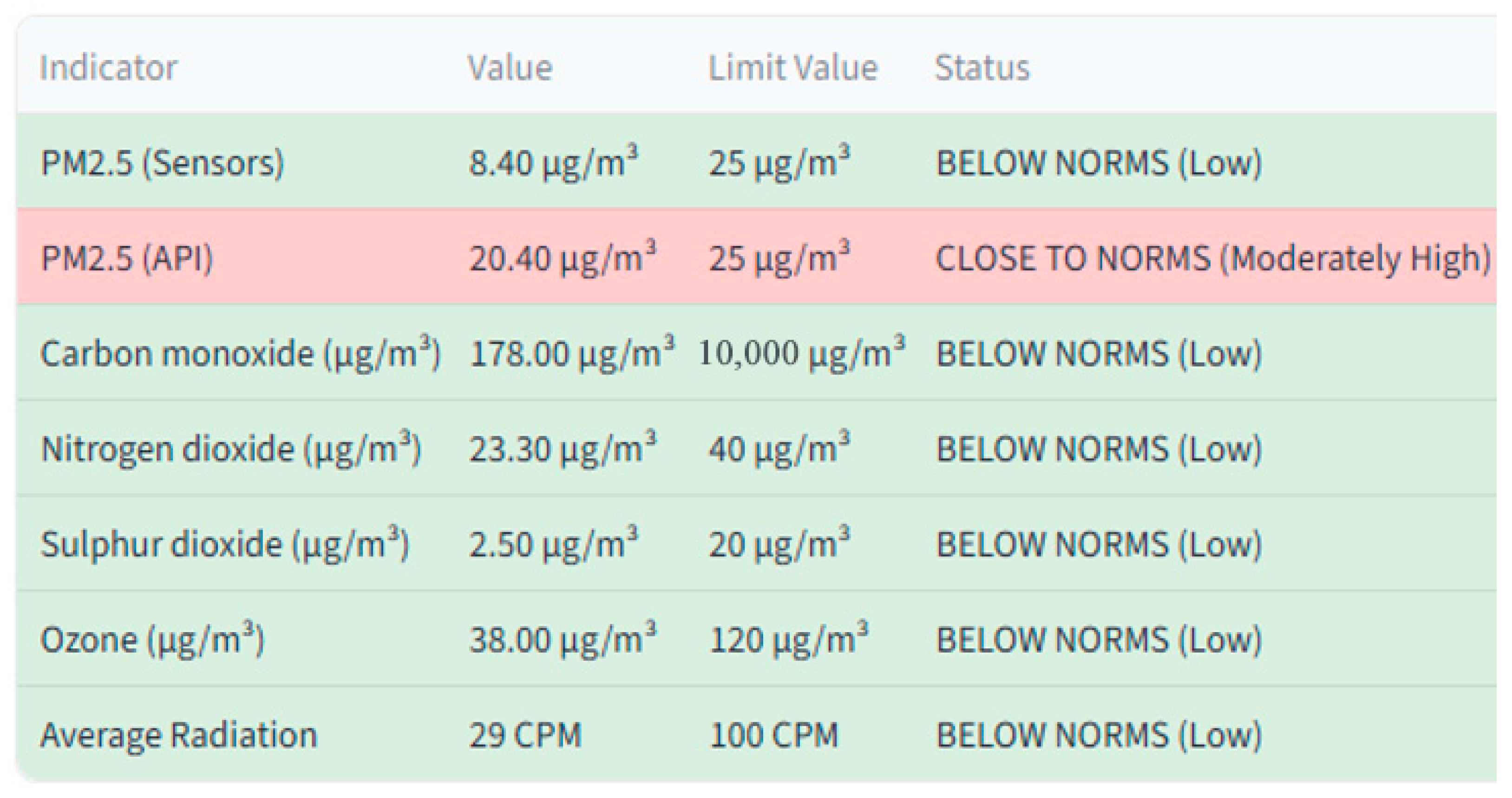

A sample from a general analysis of the air quality, generated based on the current data, is presented in

Figure 6. The AnalysisAgent uses the LLM deepseek-v3.2-exp to produce a comprehensive assessment of the conditions. Due to space limitations, the model’s response shown in the figure is a shortened version of the full analysis, displaying only the first two elements of the structured LLM report.

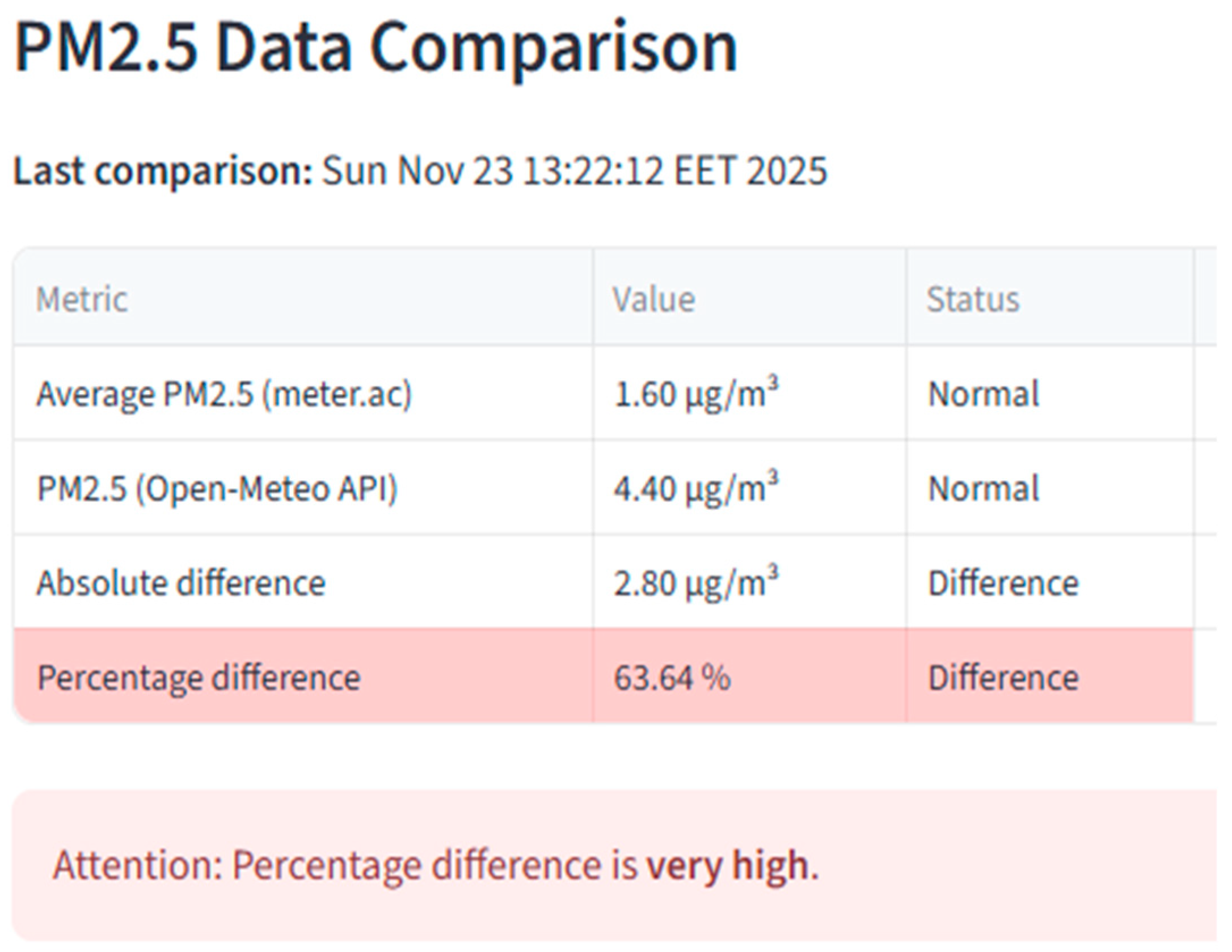

Significant discrepancies in measurements from different sources are documented by the PM25ComparisonAgent, which generates a comparative table (

Figure 7) after extracting the necessary data. European standards extracted from the specialized ontology are used as reference threshold values.

A summary overview of the measurements from two sources (ours and external) and their deviations from the norms is presented in

Figure 8. The pollutant whose instantaneous value is close to the thresholds regulated in European norms (extracted from ontology) is shown in red.

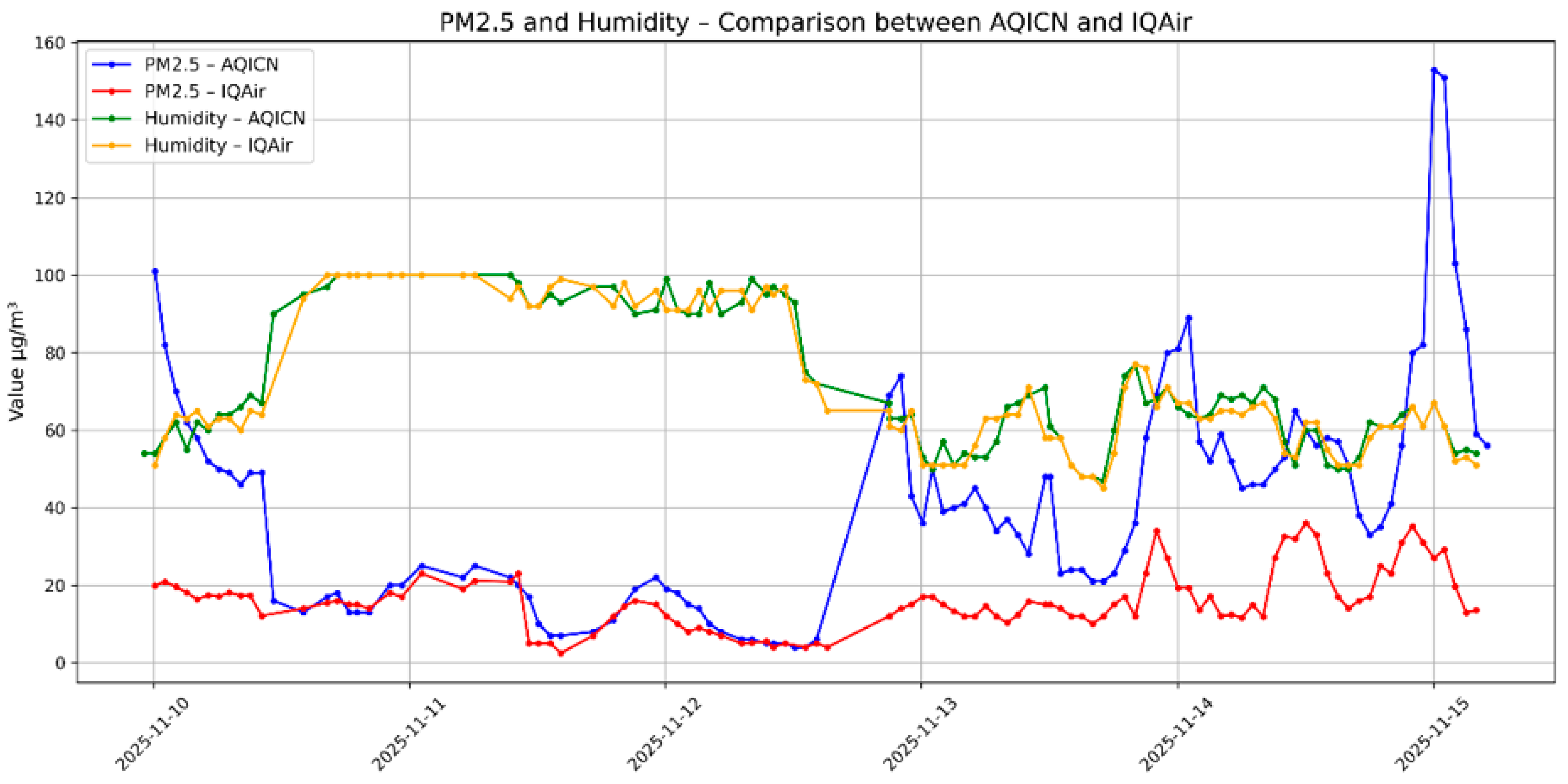

The results of the platform’s work reveal some interesting details that manually prepared analyses were unable to establish. For example, poor meteorological conditions, such as high humidity, as shown in

Figure 9, bring measurements from different sources closer together (the first half of the diagram). Such results provide ideas for different considerations in new directions and at the same time reconfirm the need to use this type of assessment and analysis tools.

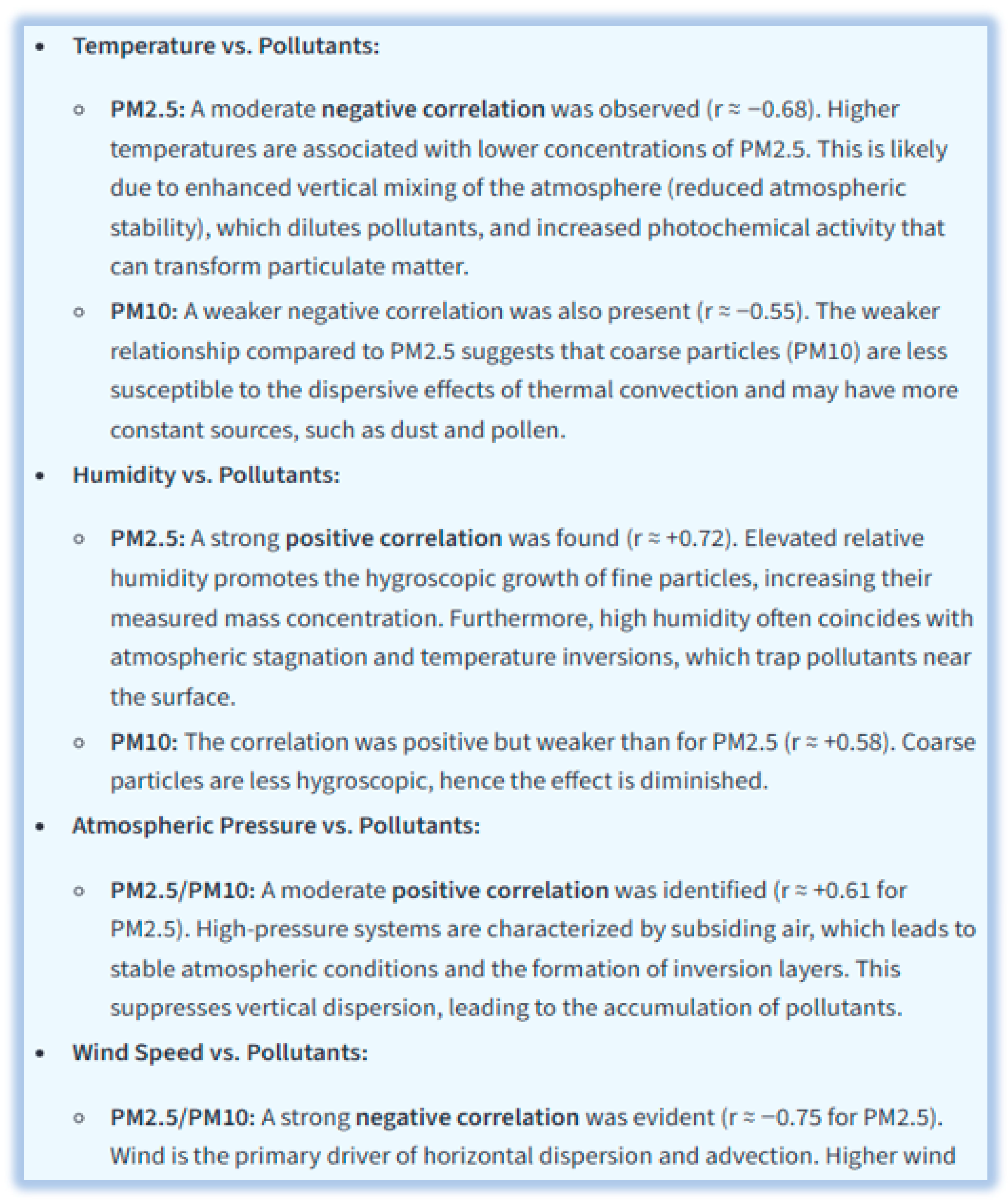

The PollutantWeatherAgent and ForecastAgent work with the same data and reach similar conclusions.

Figure 10 shows an analysis generated by the platform after PollutantWeatherAgent calls the services of LLM deepseek-v3.2-exp. This action results in an analysis that links atmospheric conditions to pollutant levels for the relevant period.

The second task we are tackling with the platform is the preparation of statistics and analysis on air quality in the Plovdiv area. In

Figure 11, the platform’s working data is shown in a clear tabular layout. The table “Data from the station in Plovdiv (meter.ac)” illustrates the sensor readings collected through the monitoring sources of Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski”, while the table “Air quality data in Plovdiv (Open-Meteo)” provides key pollution indicators obtained through the Open-Meteo API. Due to space constraints, the figure includes only a portion of the full dataset. Complete information remains accessible to users through the Streamlit interface [

42], where they can explore it interactively with flexible navigation and filtering options.

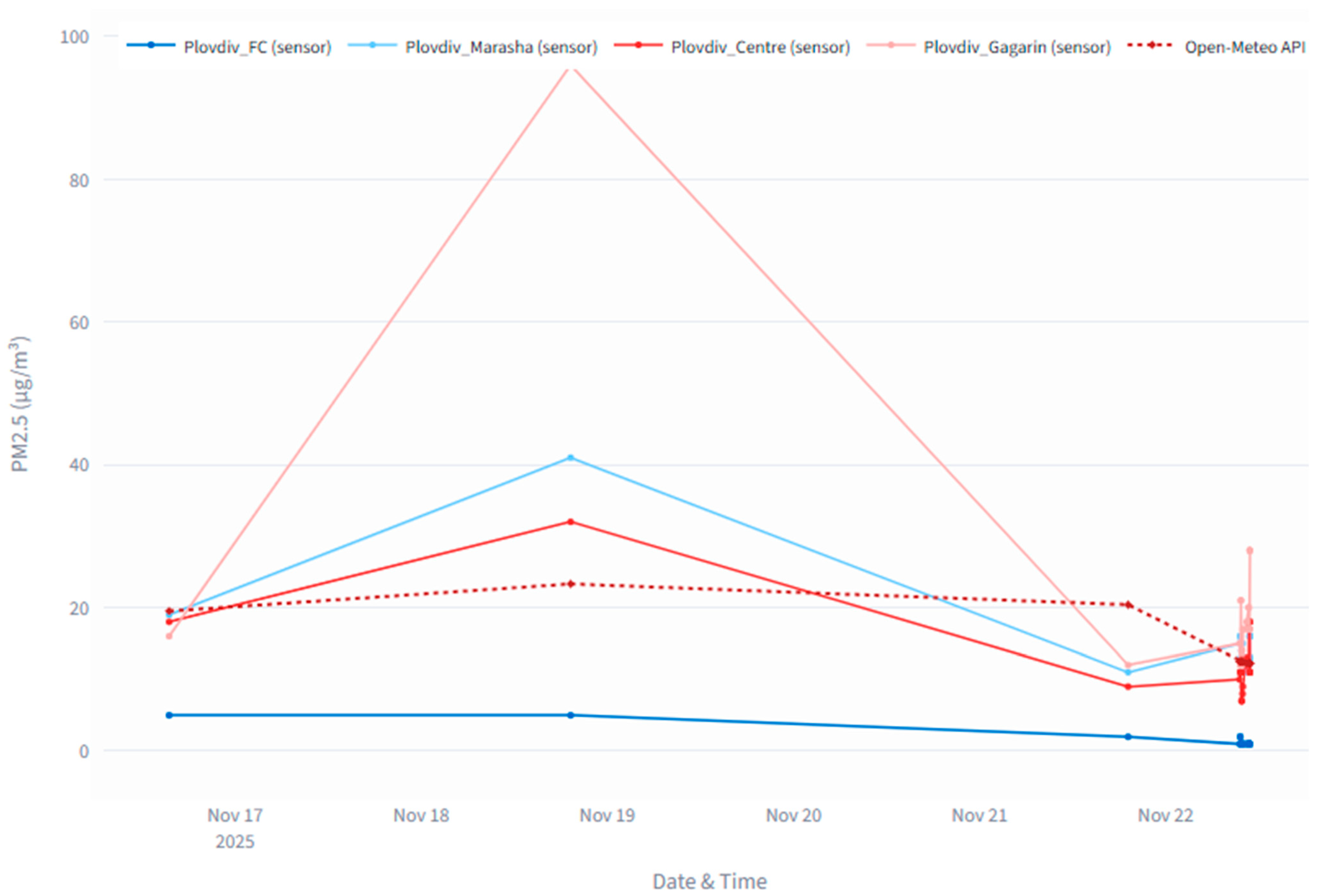

Figure 12 shows a graph that visualizes the data collected for PM

2.5 pollutant from the sensors of Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski” and from an external source via API (Open-Meteo). The differences between the various data sources are clearly distinguishable, with the difference measured for the pollutant by the university station, located in the Gagarin district of the city, and the data we receive from the external source of information, marked with a dotted line, being particularly striking. The data from the university station is significantly lower than that from the external source.

Another function of the PLAM platform is to make predictions. We will demonstrate its capabilities in this regard with two examples. Using ForecastLLMAgent, the user can request a pollution forecast for the next 24 h, and the agent generates it using LLM deepseek-v3.2-exp (

Figure 13). When applying MAE/RMSE validation in Random Forest Regressor, the selected result shows that the MAE is approximately in the range of 3–7 μg/m

3 for PM

2.5 at a 24 h forecast horizon, with a performance improvement of 18–22% over the baseline resilience-based approach. As part of the evaluation and interpretation of the results, thresholds are extracted and used from a domain-specific ontology, allowing for semantic enrichment of the predictions and more accurate classification of pollution conditions with respect to regulatory and health criteria.

When interacting with ChatAgent, the user can chat with PLAM, with the conversation limited to the topic of air pollution. In this particular case, the customer asks whether they should open their windows today, and the model generates its response based on the specific data available at that moment in order to best answer the user’s query (

Figure 14).

To verify the correctness of its operation, the PLAM platform logs actions taken by agents and communication modules in the system. Some of the logs can be seen on

Figure 15.

Although the PLAM platform is regional and developed primarily for use in the Plovdiv area, it can be adapted for other regions. Initial experiments conducted for the regions of Sofia, Varna, Burgas, and Ruse (

Figure 16) show that it can be adapted relatively easily, using public data from air quality measurements for the respective region. The difference is that for the Plovdiv region, we use additional data stored in the structured environment of the agents, which gives greater depth to the analysis. For Varna, for example, 36 exceedances of the PM

10 standards were recorded in the first three months of 2025 (

Figure 17a), and by mid-September 2025, the exceedances were 40 (

Figure 17b).

In contrast to ACreM, the following key aspects are introduced in PLAM: hybrid multi-agent architecture, evaluation across different sources, quantitative validation of forecasting, and integration of the LLM from the perspective of reproducibility. All of these elements turn the local experimental setup of the former ACreM a region-centric air quality monitoring platform PLAM.

Table 1 systematically summarizes the differences between ACreM and PLAM and clearly shows that PLAM is not an iteration of the software, but a fully expanded platform with a new system scope, architectural components, and measurable engineering characteristics. While ACreM was developed as a local experimental system focused on ontology-assisted BDI reasoning, PLAM introduces:

regionally scalable architecture;

hybrid agent model (BDI + LLM-based ReAct);

multi-source, automated comparative profiling;

quantitatively validated KPIs (latency, data volume, prediction errors).

Thus, the novelty of PLAM is simultaneously architectural, methodological, and engineer-measurable.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents a new version of a platform supporting air monitoring in the Plovdiv region. The core of the platform is a dedicated air monitoring Chain of Thought. Monitoring and analysis of air quality is demonstrated through various examples. The initial results from the platform’s operation make it possible to seek opportunities for creating a more effective infrastructure for the urban system for objective measurement of air pollutants. Analyses on our platform have identified significant differences in the measurements. Manual analysis examines individual cases and covers a small amount of data, which means that the conclusions and findings are incomplete, partial, and rather intuitive. In contrast to such analyses, those performed using the platform are complete, much more objective, and solidly substantiated. Using our platform, the first conclusion we can draw is that the general perception that there is a discrepancy in the measurements of different institutions is confirmed.

The observed discrepancies arise mainly from differences in the type and calibration of the sensors, their spatial representation, processing algorithms and temporal alignment. This is due to the fact that we do not have access to the calibration of the external sources. The external sources are considered reference for comparison, given the fact that they all have their own calibration procedures and cover a wider area. Also, unlike our sources, the external ones are certified and provide quality control procedures. It is necessary to note that PLAM is transparent about uncertainties and discrepancies and does not hide them. Objectivity in this work is determined by the operational process of source independence and consistent comparison over time.

In the future, it would be appropriate to consider the proposed platform together with existing architectural and methodological solutions for air quality monitoring and analysis. As an illustration, the inclusion of FIWARE in air quality monitoring systems is discussed in detail in [

43], presenting an IoT-based solution that integrates Cloudino and FIWARE components for sensor data collection and management. This work can be taken as a direct basis for subsequent actions, as it shows a generic platform implementation focused primarily on data collection and visualization. Therefore, the added value of our architecture, which goes beyond simply extending standard FIWARE AQM systems through semantic interoperability, integration of predictive models, and a deeper analytical layer, should be emphasized.

Furthermore, for “objective profiling” of pollution and source-related analysis, it is appropriate to use modern remote sensing methods with high spatial-temporal resolution. The article [

44] reveals a hyperspectral method for determining the hourly distribution of trace gases with a horizontal resolution of 100 m, along with accurate identification of emission sources. All this means that, in addition to conventional ground stations and public APIs, remote sensing and optical methods can significantly deepen the data ecosystem used by platforms such as PLAM, thereby extending their functionalities to determination, source identification, and attribution.

A future direction for the platform’s development is to improve our sensor networks with the ability to measure new parameters that affect air quality. We are also continuing our experiments with the aim of improving the platform’s components.

One way in which PLAM can be further developed is by creating a domain-specific language model (LLM) trained on the vocabulary, standards, ontologies, and real-world cases in the field of air quality monitoring and analysis. Such a model can act as an intelligent mediator between users and the platform, thus allowing the use of natural language for queries, obtaining self-sufficient summaries of analytical results, assisting in their interpretation, and even creating context-aware explanations (e.g., with regard to regulatory thresholds, seasonal fluctuations, meteorological conditions, and possible sources of emissions).

Our first step was to investigate and test various options for creating a specialized small language model that we could call our own. A domain-specific language model has the potential to enhance semantic interoperability by efficiently mapping and aligning the concepts of different data schemas and standards without human intervention. Moreover, by combining textual knowledge (documentation, methodologies, expert rules) and numerical measurements obtained from ground sensors and remote sensing, such a tool can also help detect anomalies. Essentially, for our research, these models represent a very effective solution for merging extremely niche, scarce information on air quality and monitoring. The small language model can be easily fine-tuned for air monitoring tasks, and at the same time, it will enhance the platform’s performance and accuracy. PLAM is intended to mainly address regional problems. Hence, we think that the use of SLM trained with region-specific datasets is a rational move. On one side, it would give us the possibility to optimize the use of our servers and also make the platform less dependent on external resources and information sources. On the other side, the SLM platform fits IoT level since it offers a combination of efficiency, low consumption of computing resources and electricity, quick response, and can provide even better security. Consequently, implementing a domain-specific language model not only aims at making the platform smarter and more functional, but it also contributes to its application in real institutional and scientific scenarios that are usually resource-constrained but can be demanding regarding autonomy and reliability.

Moreover, a recent study [

45] claims that the two factors of very rapid development along with the diversity of IoT ecosystems, on top of the fact that they have limited computing power, significantly raise the risk of cybersecurity threats. Thus, this is another reason for implementing lightweight ML/AI-based security mechanisms in IoT platforms. A detailed investigation [

46] of the IoT security area confirms the shift in the focus of new technologies, especially machine learning, anomaly detection methods, and lightweight solutions, to the core of robust IoT applications, particularly when there are real-world constraints. Concurrently, a recent paper [

47] points out that IoT security models, in turn, are increasingly victim to adversarial machine learning attacks, which can lead to a breach of the trust of ML-based decision-making in critical IoT environments. Hence, a strengthened defense against adversarial manipulation should be considered as one of the main features of IoT security architectures, along with the existing ones such as efficiency and scalability.

The feature of security and resilience in the development of the PLAM platform should probably be given substantial consideration. These two aspects are not only among the hottest topics in research at present, but they are also areas that are changing very rapidly. As the complexity of IoT-based architectures, distributed sensor networks and multi-agent systems increases, there will be a great rise in the probability of attacks on the integrity or availability of data and processes for malicious purposes. Under these conditions, ML-based intrusion detection systems (IDSs) as well as the newest domain adaptation methods can provide capable and effective assistance in detection even at large, weakly labeled IoT scenarios where the transfer of semantic knowledge is done between domains [

48]. In addition, generative AI and large language models are increasingly considered as components of the potential next-generation IoT security toolkit; therefore, they might offer solutions for threat detection, automation, and adaptive resilience strategies [

45]. On the other hand, the expansion of ML-based security mechanisms paves the way for more new vulnerabilities to be exploited, since through adversarial attacks, major IoT security frameworks such as intrusion detection systems (IDS), malware detection systems (MDS), and device identification systems (DIS) have been consistently penetrated [

47]. This thus reiterates the importance of having robust and lightweight defensive mechanisms that are capable of ensuring trustworthy operation even in adversarial conditions in the real world.

At the same time, guaranteeing that the operation is secure requires more visibility and the ability to detect devices operating in the different parts of IoT infrastructures. Previously, large language models were believed possible to be used for real-world IoT device identification by treating diverse network metadata as a language modeling task, and they surprisingly achieved high accuracy as well as robustness even when the data was noisy, incomplete, or under adversarial scenarios [

49].

The specific feature is quite relevant to PLAM, whereby it is indispensable at the device level to have trust, accountability, and anomaly detection in order to guarantee the integrity of the monitoring data streams. Meanwhile, recent reviews [

50] highlight that future IoT security solutions should be scalable, adaptive, and capable of addressing rapidly evolving threats, where emerging paradigms such as edge computing, federated learning, and explainable AI offer promising, strengthening resilience and compliance. The approaches are very important for monitoring infrastructures with limited resources, where security mechanisms should still be efficient without causing too much computational overhead.

PLAM’s future development path should be that of a platform being such a platform: rich, smart, and secure; seamlessly providing semantic interoperability; having multimodal data sources (ground-based, remote sensing, and hyperspectral); having state-of-the-art analytical and predictive models; and having built-in cybersecurity and resilience features. A comprehensive effort in such a way will change the platform from merely a monitoring tool to an academic and operational environment of a trustworthy institution for the study and management of air quality in real, dynamic, and possibly even hostile situations.

In this case, robustness withstanding not only traditional cyber threats but also adversarial manipulations of ML-based components should be taken as an unconditional prerequisite for the operational reliability of real deployments [

47,

50].