Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Uneven Environments: A Survey of Coverage and Sensor Data Collection Methods

Abstract

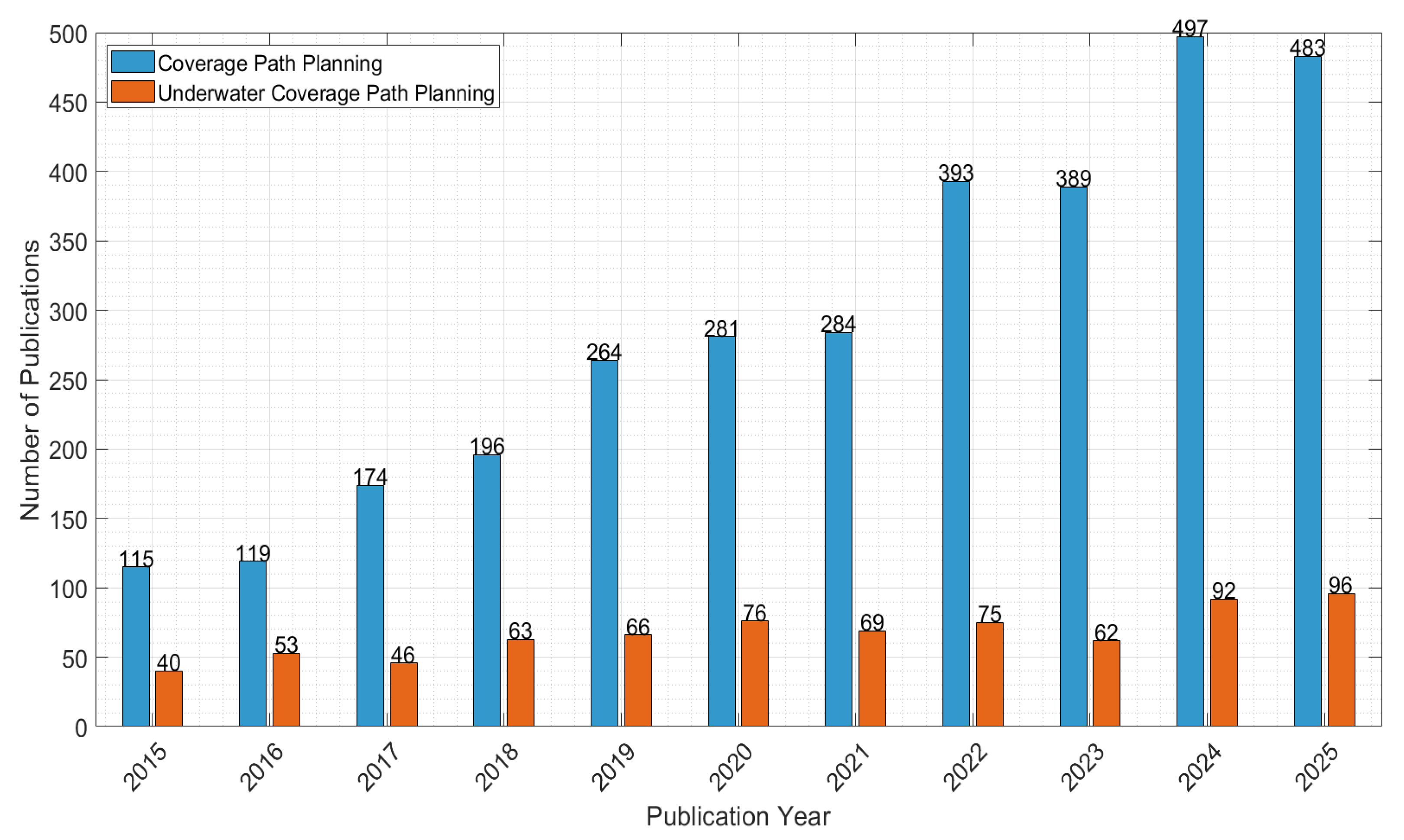

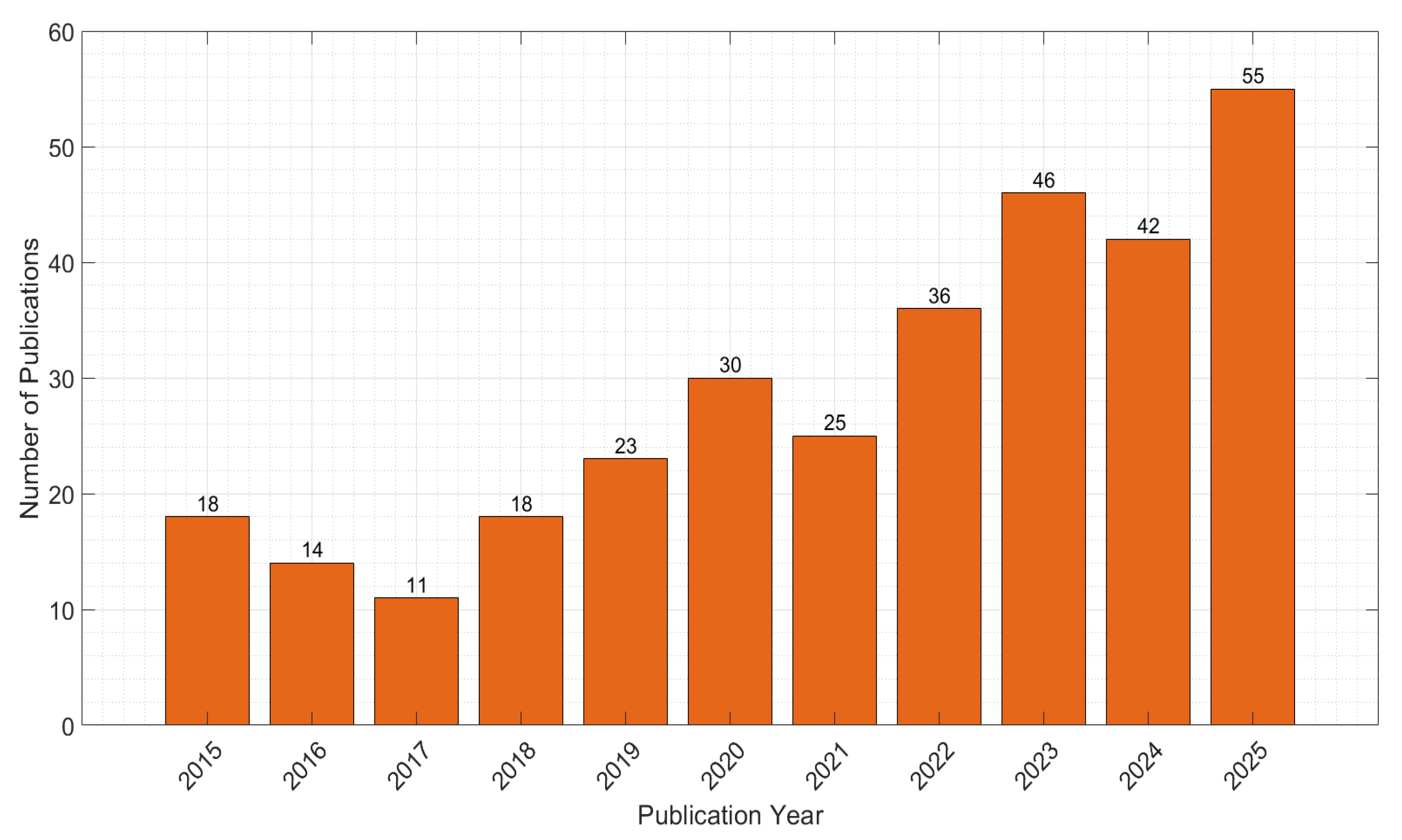

1. Introduction

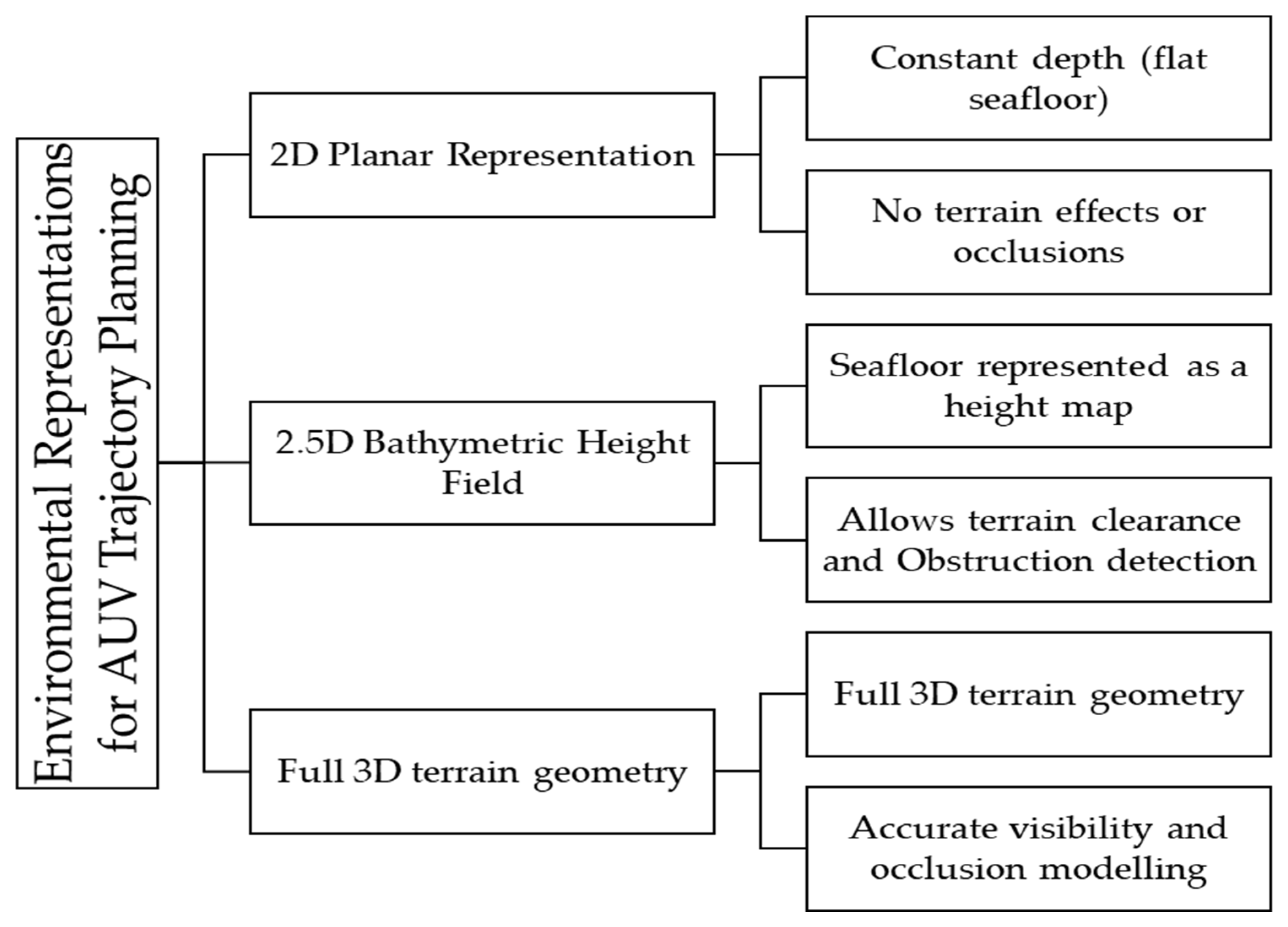

2. Fundamentals of AUV Sensing and Trajectory Planning

3. Application Domains of AUV Sensing Missions

3.1. Underwater Search and Rescue

3.2. Marine Geology and Geophysics

3.3. Underwater Archaeology

3.4. Environmental Monitoring

3.5. Underwater Seismic Data Collection

3.6. Oil Spill Detection and Cleaning

3.7. Fishing and Marine Farming

4. AUV-Based Underwater Area Coverage

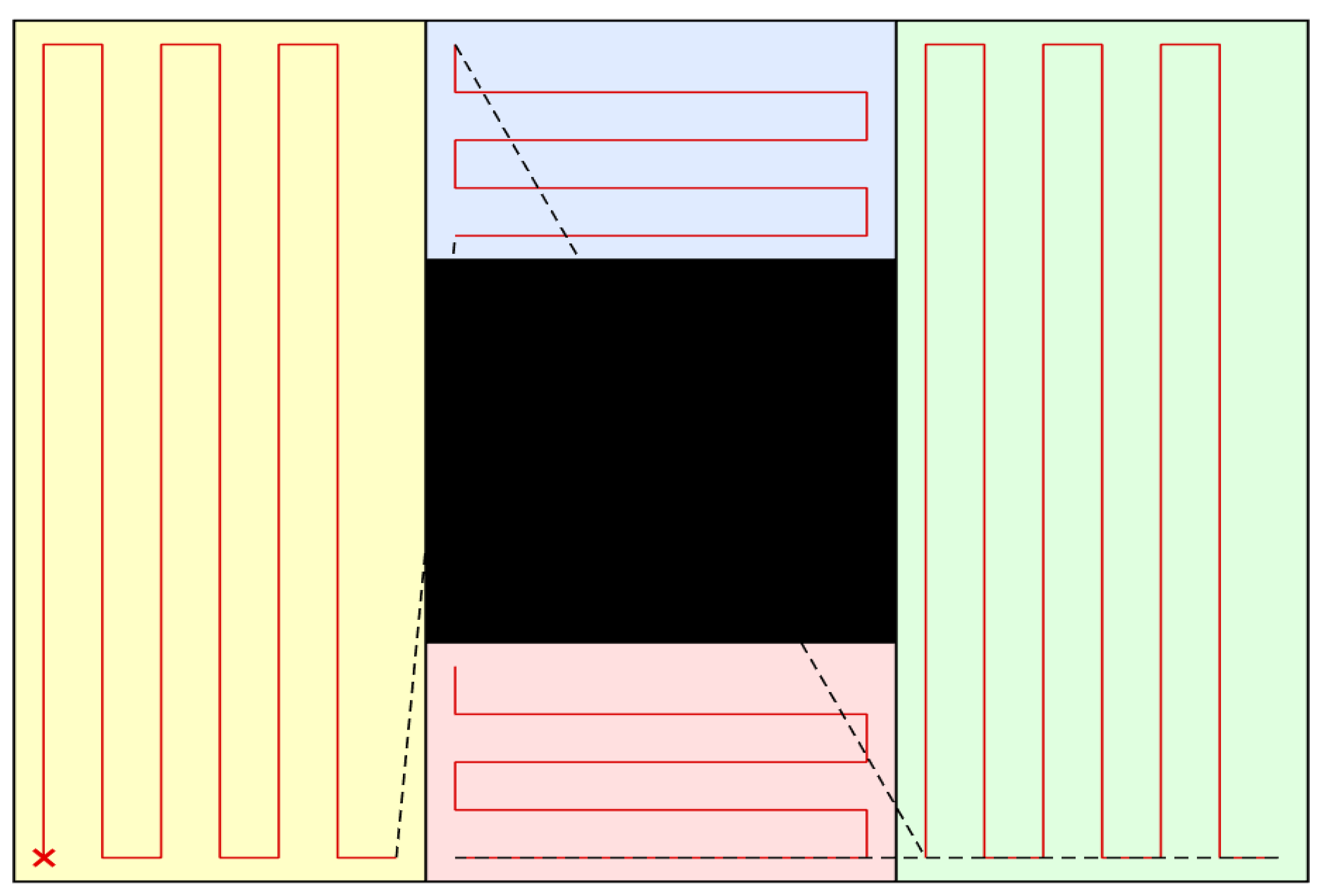

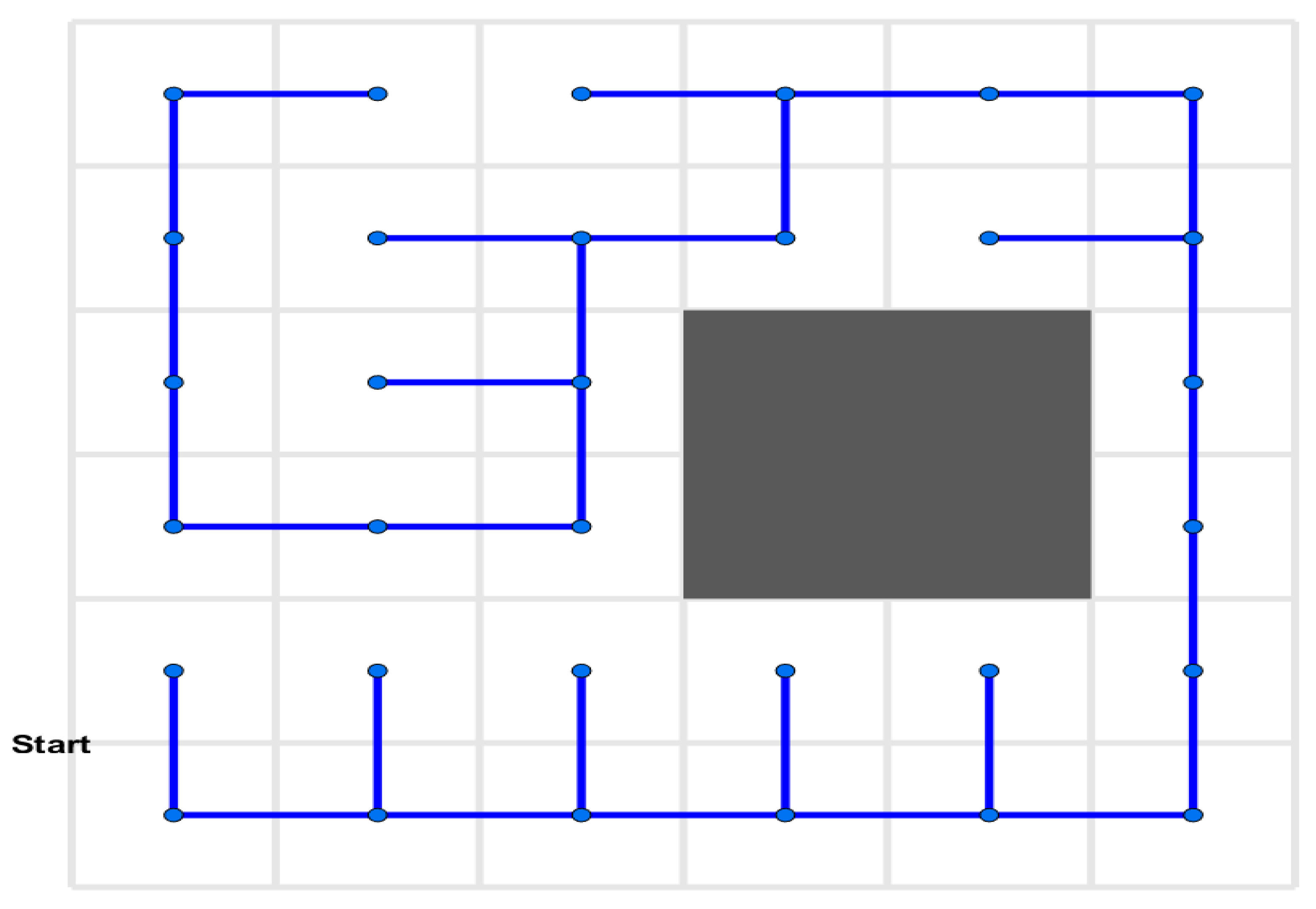

4.1. Classical Coverage Path Planning Foundations

4.2. Terrain-Aware Coverage Using Bathymetric Information

4.3. Occlusion and Visibility-Aware Coverage

4.4. Cooperative and Multi-AUV Coverage Planning

4.5. Online Coverage in Unknown or Partially Known Environments

4.6. Research Gap

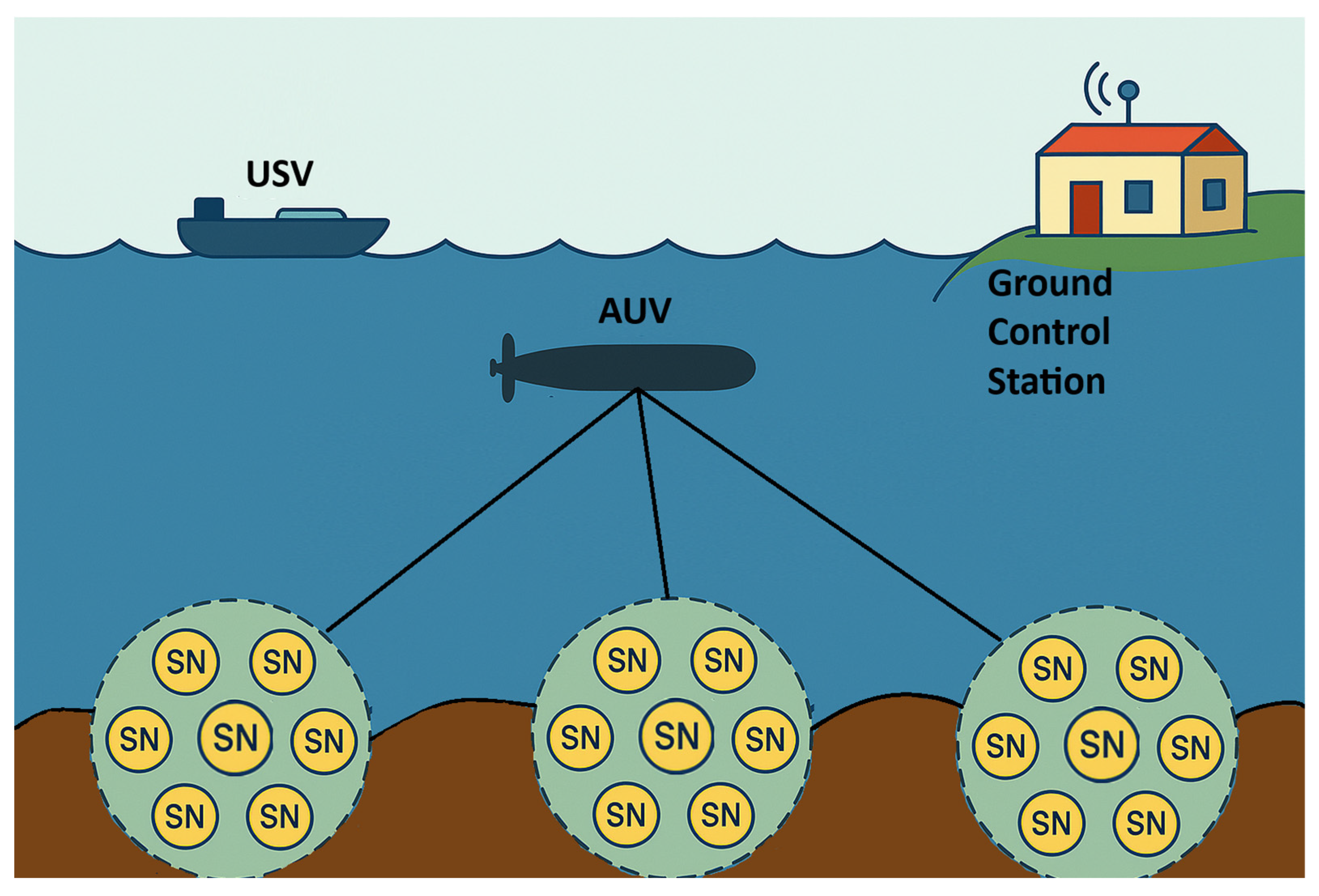

5. AUV-Based Underwater Sensor Data Collection

5.1. Energy-Aware Trajectory Planning

5.2. Channel-Aware Trajectory Planning

5.3. Information-Based Collection (AoI and VoI)

5.4. Cooperative USV-AUV Architectures

5.5. Research Gap

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUVs | Autonomous Underwater Vehicles |

| IoUT | Internet of Underwater Things |

| UASNs | Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks |

| AoI | Age of Information |

| VoI | Value of Information |

| USVs | Unmanned Surface Vehicles |

| BCD | Boustrophedon Cellular Decomposition |

| SNs | Sensor Nodes |

| CH | Cluster Head |

| WSNs | Wireless Sensor Networks |

| VBPS | VoI-based Packet Scheduling |

| ADCP | Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler |

References

- Wynn, R.B.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Le Bas, T.P.; Murton, B.J.; Connelly, D.P.; Bett, B.J.; Ruhl, H.A.; Morris, K.J.; Peakall, J.; Parsons, D.R.; et al. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): Their Past, Present and Future Contributions to the Advancement of Marine Geoscience. Mar. Geol. 2014, 352, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, A.; Piran, M.J.; Song, H.-K.; Lee, B.M. A Survey on Unmanned Underwater Vehicles: Challenges, Enabling Technologies, and Future Research Directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Bian, H. Subsea Pipeline Leak Inspection by Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2021, 107, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Du, L. AUV Trajectory Tracking Models and Control Strategies: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galceran, E.; Carreras, M. A Survey on Coverage Path Planning for Robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1258–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, P.; Du, L. Path Planning Technologies for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles—A Review. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9745–9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankiewicz, P.; Tan, Y.T.; Kobilarov, M. Adaptive Sampling with an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle in Static Marine Environments. J. Field Robot. 2021, 38, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, L.; Seto, M.; Li, H. Area Coverage Planning That Accounts for Pose Uncertainty with an AUV Seabed Surveying Application. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 6592–6599. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, S. Mosaicking of the Ocean Floor in the Presence of Three-Dimensional Occlusions in Visual and Side-Scan Sonar Images. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Technology, Monterey, CA, USA, 2–6 June 1996; pp. 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, B.M.; Ellen, J.S.; Grier, M.C. Toward Improving Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Sensing Operations through Characterization of the Impacts and Limitations of in Situ Environmental Conditions. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2022, Hampton Roads, Hampton Roads, VA, USA, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Benoist, N.M.A.; Morris, K.J.; Bett, B.J.; Durden, J.M.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Le Bas, T.P.; Wynn, R.B.; Ware, S.J.; Ruhl, H.A. Monitoring Mosaic Biotopes in a Marine Conservation Zone by Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldred, R.; Lussier, J.; Pollman, A. Design and Testing of a Spherical Autonomous Underwater Vehicle for Shipwreck Interior Exploration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chang, S.; Zou, G.; Wan, C.; Li, H. A Robust Graph-Based Bathymetric Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Approach for AUVs. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 49, 1350–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Mohd-Mokhtar, R.; Arshad, M.R. A Comprehensive Review of Coverage Path Planning in Robotics Using Classical and Heuristic Algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119310–119342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kume, A.; Maki, T.; Sakamaki, T.; Ura, T. A Method for Obtaining High-Coverage 3D Images of Rough Seafloor Using AUV—Real-Time Quality Evaluation and Path-Planning. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2013, 25, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, R.W.L.; Boukerche, A.; Vieira, L.F.M.; Loureiro, A.A.F. Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks: A New Challenge for Topology Control–Based Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.C. An Overview of the Internet of Underwater Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2012, 35, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. AUV-Aided Hybrid Data Collection Scheme Based on Value of Information for Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 6944–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, M.; Das, S.K.; Anastasi, G. Data Collection in Wireless Sensor Networks with Mobile Elements: A Survey. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2011, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.W.; Abdullah, A.H.; Anisi, M.H.; Bangash, J.I. A Comprehensive Study of Data Collection Schemes Using Mobile Sinks in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2014, 14, 2510–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Chen, C. Energy-Efficient Data Collection over AUV-Assisted Underwater Acoustic Sensor Network. IEEE Syst. J. 2018, 12, 3519–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Liu, C.; Qu, W.; Qiu, T. A Joint Optimized Data Collection Algorithm Based on Dynamic Cluster-Head Selection and Value of Information in UWSNs. Veh. Commun. 2022, 38, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Fan, X.; Lyu, W. Research Progress of Path Planning Methods for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8847863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkahraman, Ö.; Ögren, P. Efficient Navigation Aware Seabed Coverage Using AUVs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), New York City, NY, USA, 25–27 October 2021; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zacchini, L.; Franchi, M.; Bucci, A.; Secciani, N.; Ridolfi, A. Randomized MPC for View Planning in AUV Seabed Inspections. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2021, San Diego–Porto, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–23 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paull, L.; Saeedi, S.; Seto, M.; Li, H. AUV Navigation and Localization: A Review. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 39, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Du, J.; Jiang, C.; Ren, Y. Value-Based Hierarchical Information Collection for AUV-Enabled Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9870–9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillai, S.M.; Turnock, S.R.; Rogers, E.; Phillips, A.B. Experimental Analysis of Low-Altitude Terrain Following for Hover-Capable Flight-Style Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 1399–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Y.R. Task Assignment and Path Planning for Multiple Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Using 3D Dubins Curves. Sensors 2017, 17, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, B.; Khosravi, A.; Sarhadi, P. A Review of the Path Planning and Formation Control for Multiple Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 101, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Lian, L.; Sammut, K.; He, F.; Tang, Y.; Lammas, A. A Survey on Path Planning for Persistent Autonomy of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Ocean. Eng. 2015, 110, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Al Redwan Newaz, A.; Bobadilla, L.; Alsabban, W.H.; Smith, R.N.; Karimoddini, A. Towards Energy-Aware Feedback Planning for Long-Range Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 621820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Yue, G.; Zhou, N.; Chen, C. Occupancy Grid-Based AUV SLAM Method with Forward-Looking Sonar. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galceran, E.; Carreras, M. Planning Coverage Paths on Bathymetric Maps for In-Detail Inspection of the Ocean Floor. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 4159–4164. [Google Scholar]

- Almuzaini, T.S.; Savkin, A.V. Online Multi-AUV Trajectory Planning for Underwater Sweep Video Sensing in Unknown and Uneven Seafloor Environments. Drones 2025, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J. Real-Time LiDAR–Inertial Simultaneous Localization and Mesh Reconstruction. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldão, L.; de Charette, R.; Verroust-Blondet, A. 3D Surface Reconstruction from Voxel-Based Lidar Data. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 2681–2686. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Torres, M.A.; Braun, A.; Borrmann, A. SLAM2REF: Advancing Long-Term Mapping with 3D LiDAR and Reference Map Integration for Precise 6-DoF Trajectory Estimation and Map Extension. Constr. Robot. 2024, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomer, A.; Ridao, P.; Ribas, D. Inspection of an Underwater Structure Using Point-Cloud SLAM with an AUV and a Laser Scanner. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.; Cong, Z.; Xu, S.; Li, Z. Active Bathymetric SLAM for Autonomous Underwater Exploration. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2023, 130, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchini, L.; Franchi, M.; Ridolfi, A. Sensor-Driven Autonomous Underwater Inspections: A Receding-Horizon RRT-Based View Planning Solution for AUVs. J. Field Robot. 2022, 39, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.D.; Istenič, K.; Gracias, N.; Palomeras, N.; Campos, R.; Vidal, E.; García, R.; Carreras, M. Autonomous Underwater Navigation and Optical Mapping in Unknown Natural Environments. Sensors 2016, 16, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuzaini, T.S.; Savkin, A.V. Multi-Auv Path Planning for Underwater Video Surveillance Over an Uneven Seafloor. In Proceedings of the 2025 17th International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE), Perth, Australia, 20–22 March 2025; pp. 557–561. [Google Scholar]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Pompili, D.; Melodia, T. Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks: Research Challenges. Ad Hoc Netw. 2005, 3, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozs, N.; Gorma, W.; Henson, B.T.; Shen, L.; Mitchell, P.D.; Zakharov, Y.V. Channel Modeling for Underwater Acoustic Network Simulation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 136151–136175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Holdcroft, S.; Fenucci, D.; Mitchell, P.; Morozs, N.; Munafò, A.; Sitbon, J. Adaptable Underwater Networks: The Relation between Autonomy and Communications. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.C. A Topology Reorganization Scheme for Reliable Communication in Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks Affected by Shadow Zones. Sensors 2009, 9, 8684–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, X. Research Advances and Prospects of Underwater Terrain-Aided Navigation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, M.; Preisig, J. Underwater Acoustic Communication Channels: Propagation Models and Statistical Characterization. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2009, 47, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucani, D.E.; Medard, M.; Stojanovic, M. Underwater Acoustic Networks: Channel Models and Network Coding Based Lower Bound to Transmission Power for Multicast. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2008, 26, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Qiu, M. Reliable Data Collection Techniques in Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 404–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, F.; Kraemer, F.A. Value of Information in Wireless Sensor Network Applications and the IoT: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 9228–9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosta, A.; Pappas, N.; Angelakis, V. Age of Information: A New Concept, Metric, and Tool. Found. Trends® Netw. 2017, 12, 162–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, I.; Sinha, A.; Modiano, E. Optimizing Age of Information in Wireless Networks with Throughput Constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2018—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–19 April 2018; pp. 1844–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Codreanu, M.; Ephremides, A. On the Age of Information in Status Update Systems with Packet Management. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2016, 62, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9789533074320. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Li, S.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, W. Probabilistic Neighborhood-Based Data Collection Algorithms for 3D Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. Sensors 2017, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Chen, K.; Cheng, E. Joint Optimization of AoI and Energy for AUV-Assisted Data Collection in Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1580751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, J.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Cuan-Urquizo, E.; García-Valdovinos, L.G.; Salgado-Jiménez, T.; Cabello, J.A.E. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles: Localization, Navigation, and Communication for Collaborative Missions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, G.A.; Pereira, A.A.; Binney, J.; Somers, T.; Sukhatme, G.S. Learning Uncertainty in Ocean Current Predictions for Safe and Reliable Navigation of Underwater Vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2016, 33, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, S.; Wilson, P.; Ridao, P.; Petillot, Y. A Survey on Terrain Based Navigation for AUVs. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2010 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE, Seattle, WA, USA, 20–23 September 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Galceran, E.; Campos, R.; Palomeras, N.; Ribas, D.; Carreras, M.; Ridao, P. Coverage Path Planning with Real-Time Replanning and Surface Reconstruction for Inspection of Three-Dimensional Underwater Structures Using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2015, 32, 952–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeHardy, P.K.; Moore, C. Deep Ocean Search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. In Proceedings of the 2014 Oceans—St. John’s, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 14–19 September 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Moridian, B.; Mahmoudian, N. Underwater Multi-Robot Persistent Area Coverage Mission Planning. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mujeebu, M.A. The Disappearance of MH370 and the Search Operations—The Role of Technology and Emerging Research Challenges. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2016, 31, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S. AUV for Search & Rescue at Sea—An Innovative Approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV), Tokyo, Japan, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Chen, J.; Yan, Q.; Liu, F.; Zhou, R. A Prior Information-Based Coverage Path Planner for Underwater Search and Rescue Using Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) with Side-Scan Sonar. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2022, 16, 1225–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhou, N.; Han, S.; Xue, Y. An Environment Information-Driven Online Bi-Level Path Planning Algorithm for Underwater Search and Rescue AUV. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 296, 116949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Chen, J.; Yan, Q.; Liu, F. A Multi-Robot Coverage Path Planning Method for Maritime Search and Rescue Using Multiple AUVs. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Zhu, Z.; Mu, X.; Zhou, L.; Qin, H.; Bai, G. Hybrid-Algorithm-Based Emergency Search and Rescue Method with AUV to Uncertain Environment in Internet of Underwater Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 29925–29939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obembe, E.; Ali, B. Evaluating the Applications and the Growing Importance of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) in Marine Geophysical Survey. J. Sci. Innov. Technol. Res. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.; He, B. An Online Path Planning Algorithm for Autonomous Marine Geomorphological Surveys Based on AUV. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 118, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, D.D.; Pervukhin, D.A.; Davardoost, H.; Afanasyeva, O.V. Prospects for the Use of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) to Solve the Problems of the Mineral Resources Complex (MRC) of the Russian Federation. J. Marit. Res. 2024, 21, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, V.K.; Lobo, Z.; Lupanow, J.; von Fock, S.S.; Wood, Z.; Gambin, T.; Clark, C. AUV Motion-Planning for Photogrammetric Reconstruction of Marine Archaeological Sites. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 5096–5103. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Pinto, J.; Ribeiro, M.; Lima, K.; Monteiro, A.; Kowalczyk, P.; Sousa, J. Underwater Archaeology with Light AUVs. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019—Marseille, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reggiannini, M.; Salvetti, O. Seafloor Analysis and Understanding for Underwater Archeology. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 24, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotta, B.; Costanzi, R.; Ridolfi, A.; Salvetti, O.; Reggiannini, M.; Kruusmaa, M.; Salumae, T.; Lane, D.M.; Frost, G.; Tsiogkas, N.; et al. The ARROWS Project: Robotic Technologies for Underwater Archaeology. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Florence, Italy, 18 June 2018; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 364. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiogkas, N.; Saigol, Z.; Lane, D. Distributed Multi-AUV Cooperation Methods for Underwater Archaeology. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2015—Genova, Genova, Italy, 18–21 May 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciaccio, F.; Troisi, S. Monitoring Marine Environments with Autonomous Underwater Vehicles: A Bibliometric Analysis. Results Eng. 2021, 9, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Y. Data Collection Optimization of Ocean Observation Network Based on AUV Path Planning and Communication. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 282, 114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.; Forti, N.; Millefiori, L.M.; Carniel, S.; Renga, A.; Tomasicchio, G.; Binda, S.; Braca, P. Underwater Inspection and Monitoring: Technologies for Autonomous Operations. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2024, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilijević, A.; Nađ, Đ.; Mandić, F.; Mišković, N.; Vukić, Z. Coordinated Navigation of Surface and Underwater Marine Robotic Vehicles for Ocean Sampling and Environmental Monitoring. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essaouari, Y.; Turetta, A. Cooperative Underwater Mission: Offshore Seismic Data Acquisition Using Multiple Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV), Tokyo, Japan, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Tsingas, C.; Brizard, T.; Muhaidib, A. Al Seafloor Seismic Acquisition Using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Geophys. Prospect. 2019, 67, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Hollings, B.; Manning, T.; Debens, H. Development of a Novel Seismic Acquisition System Based on Fully Autonomous Ocean Bottom Nodes. Aust. Energy Prod. J. 2024, 64, S407–S410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth Kumar, S.; Jayaparvathy, R.; Priyanka, B.N. Efficient Path Planning of AUVs for Container Ship Oil Spill Detection in Coastal Areas. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 217, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bose, N.; Brito, M.; Khan, F.; Millar, G.; Bulger, C.; Zou, T. Risk-Based Path Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in an Oil Spill Environment. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 266, 113077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Mucha, A.; Santos, T.; Oliveira, A.; Amaral, G.; Ferreira, H.; Martins, A.; Almeida, J.; Silva, E. Oil Spill Mitigation with a Team of Heterogeneous Autonomous Vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubina, N.A.; Cheng, S.C. A Review of Unmanned System Technologies with Its Application to Aquaculture Farm Monitoring and Management. Drones 2022, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelasidi, E.; Su, B.; Caharija, W.; Føre, M.; Pedersen, M.O.; Frank, K. Autonomous Monitoring and Inspection Operations with UUVs in Fish Farms. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenius, I.; Folkesson, J.; Bhat, S.; Sprague, C.I.; Ling, L.; Özkahraman, Ö.; Bore, N.; Cong, Z.; Severholt, J.; Ljung, C.; et al. A System for Autonomous Seaweed Farm Inspection with an Underwater Robot. Sensors 2022, 22, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowmmiya, U.; Roselyn, J.P.; Sundaravadivel, P. Integrating Edge-Intelligence in AUV for Real-Time Fish Hotspot Identification and Fish Species Classification. Information 2024, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Gao, W. Coverage Path Planning for Multi-AUV Considering Ocean Currents and Sonar Performance. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1483122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, K.P.; Nair, V.G.; Sathish, D. A Comprehensive Survey on Coverage Path Planning for Mobile Robots in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 60158–60185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choset, H.; Pignon, P. Coverage Path Planning: The Boustrophedon Cellular Decomposition. In Proceedings of the Field and Service Robotics; Zelinsky, A., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 1998; pp. 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Savkin, A.V.; Huang, H. Asymptotically Optimal Path Planning for Ground Surveillance by a Team of UAVs. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3446–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choset, H. Coverage for Robotics—A Survey of Recent Results. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2001, 31, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriely, Y.; Rimon, E. Spanning-Tree Based Coverage of Continuous Areas by a Mobile Robot. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2001, 31, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Roman, C.; Pizarro, O.; Eustice, R.; Can, A. Towards High-Resolution Imaging from Underwater Vehicles. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2007, 26, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Roberson, M.; Pizarro, O.; Williams, S.B.; Mahon, I. Generation and Visualization of Large-Scale Three-Dimensional Reconstructions from Underwater Robotic Surveys. J. Field Robot. 2010, 27, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, L.A.M.; Blackmore, L.; Williams, B.C. AUV Bathymetric Mapping Depth Planning for Bottom Following Splice Linear Programming Algorithm. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Englot, B.; Hover, F. Sampling-Based Coverage Path Planning for Inspection of Complex Structures. Proc. Int. Conf. Autom. Plan. Sched. 2012, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, I.S.; Bernalte Sánchez, P.J.; Papaelias, M.; Márquez, F.P.G. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles and Field of View in Underwater Operations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrampoulidis, C.; Shulkind, G.; Xu, F.; Freeman, W.T.; Shapiro, J.H.; Torralba, A.; Wong, F.N.C.; Wornell, G.W. Exploiting Occlusion in Non-Line-of-Sight Active Imaging. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2018, 4, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Pinto, J.; Dias, P.S.; Sujit, P.B.; Sousa, J.B. Multiple Underwater Vehicle Coordination for Ocean Exploration. Intl. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell. 2009, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Hao, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Ren, R. Multi-Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Full-Coverage Path-Planning Algorithm Based on Intuitive Fuzzy Decision-Making. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Tian, C.; Jiang, X.; Luo, C. Multi-AUVs Cooperative Complete Coverage Path Planning Based on GBNN Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 29th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 May 2017; pp. 6761–6766. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Feng, X. Multi-AUV Coverage Path Planning Algorithm Using Side-Scan Sonar for Maritime Search. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 300, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell-Torres, A.; Guerrero-Sastre, J.; Oliver-Codina, G. Coordination of Marine Multi Robot Systems with Communication Constraints. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2024, 142, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, D.; Pang, W.; Zhang, Y. A Survey of Underwater Search for Multi-Target Using Multi-AUV: Task Allocation, Path Planning, and Formation Control. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 278, 114393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Beaujean, P.-P.J.; An, E.; Carlson, E. Task Allocation and Path Planning for Collaborative Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Operating through an Underwater Acoustic Network. J. Robot. 2013, 2013, 483095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekleitis, I.M.; Dudek, G.; Milios, E.E. Multi-Robot Exploration of an Unknown Environment, Efficiently Reducing the Odometry Error. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 1340–1345. [Google Scholar]

- MahmoudZadeh, S.; Yazdani, A. Distributed Task Allocation and Mission Planning of AUVs for Persistent Underwater Ecological Monitoring and Preservation. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 290, 116216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhoun, R.; Taha, T.; Seneviratne, L.; Zweiri, Y. A Survey on Multi-Robot Coverage Path Planning for Model Reconstruction and Mapping. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Saha, I. Scalable Online Coverage Path Planning for Multi-Robot Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 10102–10109. [Google Scholar]

- Paull, L.; Saeedi, S.; Seto, M.; Li, H. Sensor-Driven Online Coverage Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2013, 18, 1827–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shi, J. An Uncertainty-Driven Sampling-Based Online Coverage Path Planner for Seabed Mapping Using Marine Robots. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Symposium (AUV), Singapore, 19–21 September 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ma, M.; Cao, J.; Luo, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, W. A Method for Multi-AUV Cooperative Area Search in Unknown Environment Based on Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, D.; Luo, G. A Static Area Coverage Algorithm for Heterogeneous AUV Group Based on Biological Competition Mechanism. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 845161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Yates, R.; Gruteser, M. Real-Time Status: How Often Should One Update? In Proceedings of the 2012 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM, Orlando, FL, USA, 25–30 March 2012; pp. 2731–2735. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.C.; Roy, S.; Jain, S.; Brunette, W. Data MULEs: Modeling and Analysis of a Three-Tier Architecture for Sparse Sensor Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2003, 1, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Uma, R.N.; Abay, B.H.; Wu, W.; Wang, W.; Tokuta, A.O. Minimum Latency Multiple Data MULE Trajectory Planning in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2014, 13, 838–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temene, N.; Sergiou, C.; Georgiou, C.; Vassiliou, V. A Survey on Mobility in Wireless Sensor Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 125, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Yu, G.; Qu, F.; Sun, R. AUV-Aided Energy-Efficient Data Collection in Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 10010–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.R.; Ahmed, S.H.; Jembre, Y.Z.; Kim, D. An Energy-Efficient Data Collection Protocol with AUV Path Planning in the Internet of Underwater Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 135, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Sun, M.; Peng, Z.; Guo, J.; Cui, J.; Qin, B.; Cui, J.-H. A Channel-Aware AUV-Aided Data Collection Scheme Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.A. Information Value Theory. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1966, 2, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Wu, W.; Tang, L.; Qu, F.; Shen, X. Value of Information-Based Packet Scheduling Scheme for AUV-Assisted UASNs. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 7172–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Tang, Y.; Jin, M.; Jing, L. An AUV-Assisted Data Gathering Scheme Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for IoUT. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Liu, L. Link Strength for Unmanned Surface Vehicle’s Underwater Acoustic Communication. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/OES China Ocean Acoustics (COA), Harbin, China, 9–11 January 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Françolin, C.C.; Rao, A.V.; Duarte, C.; Martel, G. Optimal Control of a Surface Vehicle to Improve Underwater Vehicle Network Connectivity. J. Aerosp. Comput. Inf. Commun. 2012, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savkin, A.V.; Verma, S.C.; Anstee, S. Optimal Navigation of an Unmanned Surface Vehicle and an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Collaborating for Reliable Acoustic Communication with Collision Avoidance. Drones 2022, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xie, G.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, S. USV-AUV Collaboration Framework for Underwater Tasks under Extreme Sea Conditions. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025–2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari, M.; Savkin, A.V. Kinodynamic Motion Model-Based MPC Path Planning and Localization for Autonomous AUV Teams in Deep Ocean Exploration. In Proceedings of the 2025 33rd Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Tangier, Morocco, 10–13 June 2025; pp. 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari, M.; Savkin, A.V.; Deghat, M. Integrated Path Planning and Localization for an Ocean Exploring Team of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles with Consensus Graph Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2026, 11, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuzaini, T.S.; Savkin, A.V. AUV Trajectory Planning for Optimized Sensor Data Collection in Internet of Underwater Things. Future Internet 2025, 17, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Known Environment 1 | Unknown Environment 2 | Single AUV | Multiple AUVs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7,8,24,34] |  |  | ||

| [9,15,116,117] |  |  | ||

| [93,106] |  |  | ||

| [118,119] |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Almuzaini, T.S.; Savkin, A.V. Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Uneven Environments: A Survey of Coverage and Sensor Data Collection Methods. Future Internet 2026, 18, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020079

Almuzaini TS, Savkin AV. Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Uneven Environments: A Survey of Coverage and Sensor Data Collection Methods. Future Internet. 2026; 18(2):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020079

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmuzaini, Talal S., and Andrey V. Savkin. 2026. "Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Uneven Environments: A Survey of Coverage and Sensor Data Collection Methods" Future Internet 18, no. 2: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020079

APA StyleAlmuzaini, T. S., & Savkin, A. V. (2026). Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Uneven Environments: A Survey of Coverage and Sensor Data Collection Methods. Future Internet, 18(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18020079