To evaluate the performance, scalability, and data integration of G-IDSS, we designed and carried out a series of experiments to validate its core components: P2P overlay, peer communication, DBMS, data querying mechanisms, and data integration. This section outlines the experimental setup, the types of experiments conducted, and the specific validation strategies for each component, focusing on peer communication, overlay maintenance, database operations, query execution and effectiveness, data integration for each operation, and scalability with regard to computing resources.

4.1. Experimental Setup

Experiments were conducted on various scales to validate the prototype as a proof of concept. Four main testing setups were used based on the required experiments and computing power. The first setup involved a basic GitHub Codespace with 8 GB of memory, 2 Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8370C CPUs at 2.80 GHz, and 32 GB of disk space, which will be referred to as the codespace from now on. The second setup involved a virtual machine on a PC with 32 GB of RAM, an 11th-generation Intel Core i7-10710U CPU at 1.10 GHz, and 500 GB of SSD storage. The VM instance was based on a Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) running Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS, with 16 GB of memory and 12 logical processors, which we will now refer to as WSL. The third setup involved a server machine running Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS, with 2 Intel(R) Xeon(R) 12 cores CPUs at 2.00 GHz, 64 GB of memory, and 3 TB of disk space, which will be referred to as gridsurfer from now on. The fourth setup used another high-performance server running Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS, with Intel(R) Xeon(R) W-2495X 40-core CPUs, 255 GB of memory, and 6 TB of storage, which will be referred to as datadog from now on. The prototype’s codebase is primarily implemented in Go (version 1.21) for P2P overlay and database functionality, and its downloadable repository is available on GitHub (

https://github.com/cafaro/IDSS/tree/main accessed on 17 December 2025). A bash script was used to simulate the peers on an overlay, and Python was used to generate synthetic data to populate graph storage. Protobuf was used in the implementation to facilitate stream communication between peers and message serialisation. A specific release related to test results reported in this manuscript is available on GitHub (

https://github.com/Lunodzo/idss_graphdb/releases/tag/gidssv01 accessed on 17 December 2025).

The experiments were conducted by running multiple G-IDSS peers and clients, with each G-IDSS peer hosting its own dataset. Clients were run in different fashions to test the G-IDSS ability to handle multiple client requests and to respond accordingly. During experiments, the number of peers varied from 10 to 10,000 to assess for system’s scalability, with each peer running an instance of the EliasDB graph database and the libp2p-based P2P stack. Synthetic data populated each peer’s database with 10 client nodes, 100 consumption nodes, and 1000 belongs_to edges, unless specified otherwise in the experiments testing scalability. In such scenarios, we generated two graph nodes per peer, allowing the experiment to allocate compute resources to accommodate an increasing number of peers rather than using them for synthetic data generation. The Kademlia DHT was initialised with a subset of peers as bootstrap nodes, and the Noise protocol ensured secure communication among peers. Performance metrics were collected using the built-in pprof server (localhost:6060) and custom logging (go-log/v2). Each experiment was repeated several times to draw concrete conclusions and to record the best observed performance.

4.2. Overlay Establishment

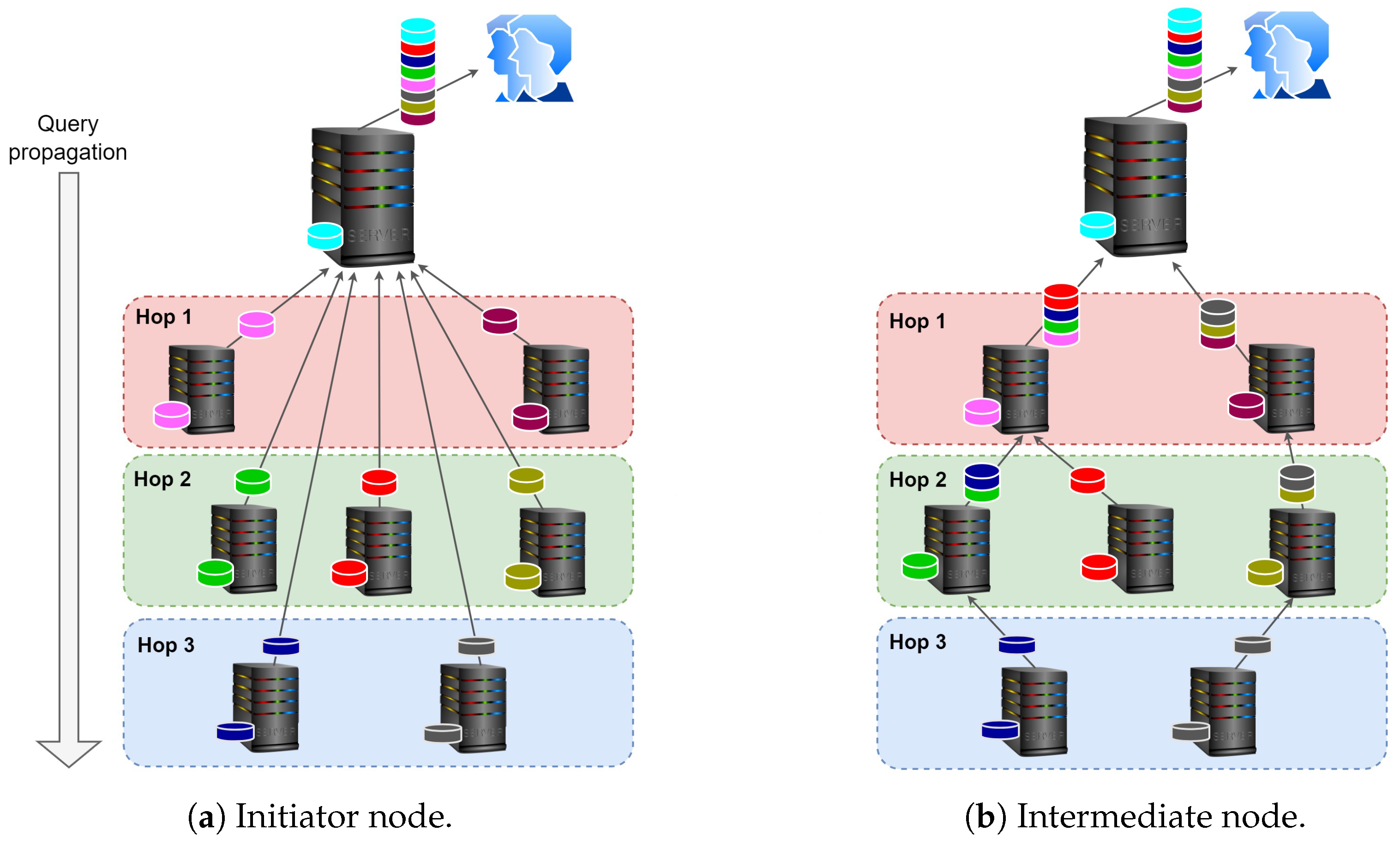

In this experiment, the study primarily focused on two key metrics: peer communication and its scalability. In peer communication, during all experiments, peers were able to efficiently create their IDs and overlay properties and then join the G-IDSS overlay (which is launched with its own service tag and protocol). The number of peers during experiments was 10–100 in the codespace, 200 in WSL, 1500 on gridsurfer, and up to 10,000 peers on datadog. While similar scalability test reports for libp2p and other P2P libraries are scarce in the research space, other (unreviewed) experiments using the IPFS DHT with Go-libp2p reportedly enabled the launch of up to 1000 concurrent peer connections, after which streams were automatically reset. Some libp2p implementations written in Rust reported that nodes can maintain up to 10,000 peer connections, including more than 1500 validator connections (

https://github.com/libp2p/rust-libp2p/discussions/3840?utm accessed on 17 December 2025). Currently, there are notable research works that have proposed approaches to enable DHTs to scale to millions of peers [

49]. This implies that scaling to 100,000 nodes with libp2p is viable if the per-node peer degrees remain around 100 connections. It is worth noting that the limited computational resources can limit scalability when experimenting with P2P overlays on a single machine. However, with peer discovery mechanisms (mDNS, DHT, and bootstrap nodes), scalability can be further improved because peers do not need to maintain a full connection to each other. Existing scalability evaluations of well-known P2P overlays demonstrate substantial progress, though largely through controlled studies. Early structured overlays, such as Chord, have been shown to scale to approximately 10,000 peers using a P2P simulator [

50], while Pastry and the gossip-enhanced DHT-like system Kelips report scalability up to 100,000 simulated peers [

51,

52]. More recent Kademlia-based deployments—including the BitTorrent Mainline DHT and related variants—have been evaluated at scales of more than a million nodes, either through large-scale simulations or real-world measurements [

53,

54].

In our experiments, the observed limits on the number of peers that we launched were due to resource exhaustion during the launch process. This improves if the launch process is performed in chunks, especially when launching more than 1000 peers. Maintaining an overlay does not require significant computational resources, mainly because we have set the routing table to refresh once every hour, and each peer maintains only a partial connection to all peers in the overlay. Libp2p also maintains a bucket size of 20 peers in the routing table, which is configurable depending on the requirements. This means that the computing required increases depending on DHT configurations. Important parameters to consider in such scenarios include the number of peers in the overlay, periodic discovery, routing table updates, liveness checks, handling new connections, and necessary data exchange during overlay population. Furthermore, since encryption of communication is required, key exchange operations should also be considered.

The observed failures were also due to the synthetic data generation process, rather than peer communication itself. This was the case in our experiments because, for a peer to join an overlay, we required them to have a graph data manager and some data loaded into it, which can be a slightly slower process depending on the data size. Hence, to test the maximum number we could launch, we had to set synthetic data generation to the minimum number of nodes and edges.

4.3. Database Management and Data Querying

This experiment aimed to test the tool’s capabilities for data management in terms of querying and integration in a decentralised fashion. For convenience, experiments on data querying and integration were conducted with 10–100 peers for WSL, 10–1000 nodes for gridsurfer, and 100–5000 peers for datadog, comprising 10-to-5 million graph nodes, to prove that decentralised graph data can be queried and integrated in a common format.

Each peer joining an overlay is mandated to host a graph DBMS before joining the network. Given the number of peers, this was successful in all experiments, and all peers involved in testing had both DBMS and graph data loaded. The results described in this section are based on query performance in the context of P2P distributed databases.

G-IDSS implements all basic queries supported by EQL’s syntax. Since their retrieval patterns involve fetching nodes under conditions like =, !=, | <, > |, as well as contain like and arithmetic operators, running such queries in distributed environments requires simple data aggregation methods among peers. Example queries may include the following:

get Client;

get Consumption traverse ::: where name = “Alice”;

lookup Client ’3’ traverse :::;

get Client traverse owner: belongs_to: usage: Consumption;

get Client show name.

The traversal expressions indicated by ::: provide a way to traverse the edges to fetch nodes and edges that are connected to each other (an equivalence to relationships in relational databases). The traversal statements may be followed by relational operators to filter data nodes/edges that comply with a condition given, i.e.,

The EQL comes with the built-in COUNT function, which can be useful in data querying. For instance, it can be used to fetch nodes that have a certain number of connections (relationships). In this regard, when the count number is set to greater than zero, the query returns all nodes in the graph that are connected to each other and have at least one connection, so any connected node will be returned. Possible queries are presented in

Table 5.

When such queries are run in a distributed fashion, they require only result aggregation among peers. However, this is not the case when performing queries that include additional functions, such as sorting datasets or computing the average of data values in a distributed manner. G-IDSS supports the distributed sorting of results using built-in EQL capabilities. To sort data, EQL uses the WITH clause, which is followed by the ordering command, for which a query has to specify an ascending or descending directive, and this is followed by a property to which one wants to refer for sorting, as indicated below. EQL also allows the use of show command to only return a specified property/column.

We run test queries by launching up to 100 peers, each having a varied number of graph nodes. We chose two cases which can basically represent a minimal and reasonably high number of graph nodes that can be fetched in a decentralised fashion, as summarised below.

Case 1: Few peers with huge data load. This is conducted through an experiment that launches 10 peers with a large dataset comprising 100,000 client nodes, 1,000,000 consumption nodes, and 1,000,000 edges across the entire overlay. On the other hand, the experiment involved launching 1000 graph nodes in each peer, running between 10–5000 peers in WSL, gridsurfer, and datadog.

Case 2: Increased number of peers with a few data. This is conducted by launching 100 peers with 1000 client nodes, 10,000 consumption nodes, and 10,000 edges across the entire overlay. Furthermore, experiments were conducted on the same machines used in Case One, this time loading peers with only 10 graph nodes per peer, to understand the variation in performance due to system dynamics.

The two scenarios will presumably generalise the complexities of data fetching in a few-peer environment and in an increased number of peers environment, demonstrating the impact of querying complexities in a scaling network. Three basic queries were considered based on the nature of the result set they return. First, get Client; second, get Consumption; and, third, get Consumption traverse :::. These queries aggregate data from peer-to-peer integration and traverse across nodes, enabling decentralised querying across traversed data. All peers and data generation were initiated by the prepared bash script to automate background tasks. With a single client launched, we tested all query types described in this section.

4.3.1. Case 1: Loading Huge Datasets

With 10 peers, the first case query returned all results in 4-to-10 s, fetching data between 1000 and 100,000 across the entire overlay. As a result, we extended the experiments for this use case by testing different numbers of peers with 1000 graph nodes per peer, resulting in 10,000 graph nodes across 10 peers, 20,000 across 20 peers, and 1,000,000 across 1000 peers. These experiments were run in WSL, gridsurfer, and datadog. The WSL accommodated up to 100 peers in this case, with 100,000 graph nodes. Hence, it was able to fetch all the results in 60 s, 67% of the results in 30 s, and it fetched results in only 1 peer when launching a query between 1 and 10 s. A summary of WSL experiment results is presented in

Table 6.

The same experiment was repeated on gridsurfer, where, with the same number of peers and data size simulated in WSL, G-IDSS was able to fetch all results in 30 s and more than half in 10 s. The summary of gridsurfer test results is presented in

Table 7.

We finally ran the same experiment in the datadog, which is the best machine among others involved in the test. The datadog machine was loaded with the same amount of data as for gridsurfer and WSL. In the case of peers, datadog launched 100-to-5000 peers. The experiment demonstrated the capacity of datadog to fetch all loaded datasets in 30 s while hosting up to 1000 peers. With 5000 peers, datadog was able to fetch up to 50% of the entire dataset in 60 s. This test has shed an important light that, with the existence of many peers, small TTL values would not be able to fetch the best result for consumption. The summary of its performance is presented in

Table 8.

4.3.2. Case 2: Scaling Number of Peers

With an increased number of peers containing fewer datasets, G-IDSS generally takes longer time to fetch the required results. The goal of this experiment was to observe how many peers each testing platform would be able to accommodate. G-IDSS was able to fetch all results in at least 30 s given a WSL machine, 10 s for the gridsurfer machine, and 1 s for datadog, all with 100 peers. Furthermore, we carried out additional experiments testing different peer sizes. In this case, every peer in the overlay had only 10 graph nodes. With WSL, G-IDSS was able to fetch all the results within 30 s while simulating with 50 peers. With 100 peers, the WSL fetched 89% of the required results in 30 s, 32% in 10 s, and 14% in 1 s. A summary of these results is presented in

Table 9.

On the other hand, G-IDSS on gridsurfer fetched all results from 100 peers within 30 s. In 10 s, G-IDSS fetched 42% of the required results. Furthermore, 1 s was enough to fetch all results in 10 and 20 peers. A summary of these results is presented in

Table 10.

We, lastly, simulated the experiments in datadog. In the tests, G-IDSS fetched all loaded results in 10 s while launching 1000 peers. With 5000 peers, G-IDSS fetched 80% of all results in 60 s. With 1 s, only 1% of the data was fetched. Other results are summarised in

Table 11.

We also conducted small-scale tests to observe the impact of the TTL value on querying. We ran the test by launching 50 peers, each with 10 client nodes (resulting in 500 clients in the overlay), 100 consumption records (resulting in 5000 consumption records in the overlay), and 5000 edges (each client node having 100 edges, representing direct connections to consumption records). A “get Client” query, executed with a TTL equal to 3, returned a total of 330 records, indicating that 33 out of 50 peers were successfully reached and returned the results. Running the same query with an increased TTL value of 6, G-IDSS was able to fetch all 500 client nodes, thereby reaching all peers in the overlay. Query traversal can also be run in G-IDSS to search for targeted records. For instance, the query traversal “get Client traverse owner: belongs_to: usage: Consumption” retrieves all client records with their associated consumption records in 7 s, i.e., these are two nodes connected through an edge with a connection pattern described as “owner: belongs_to: usage: Consumption”. A detailed description of submitted queries and fetched results is provided in the GitHub repository. As stated in [

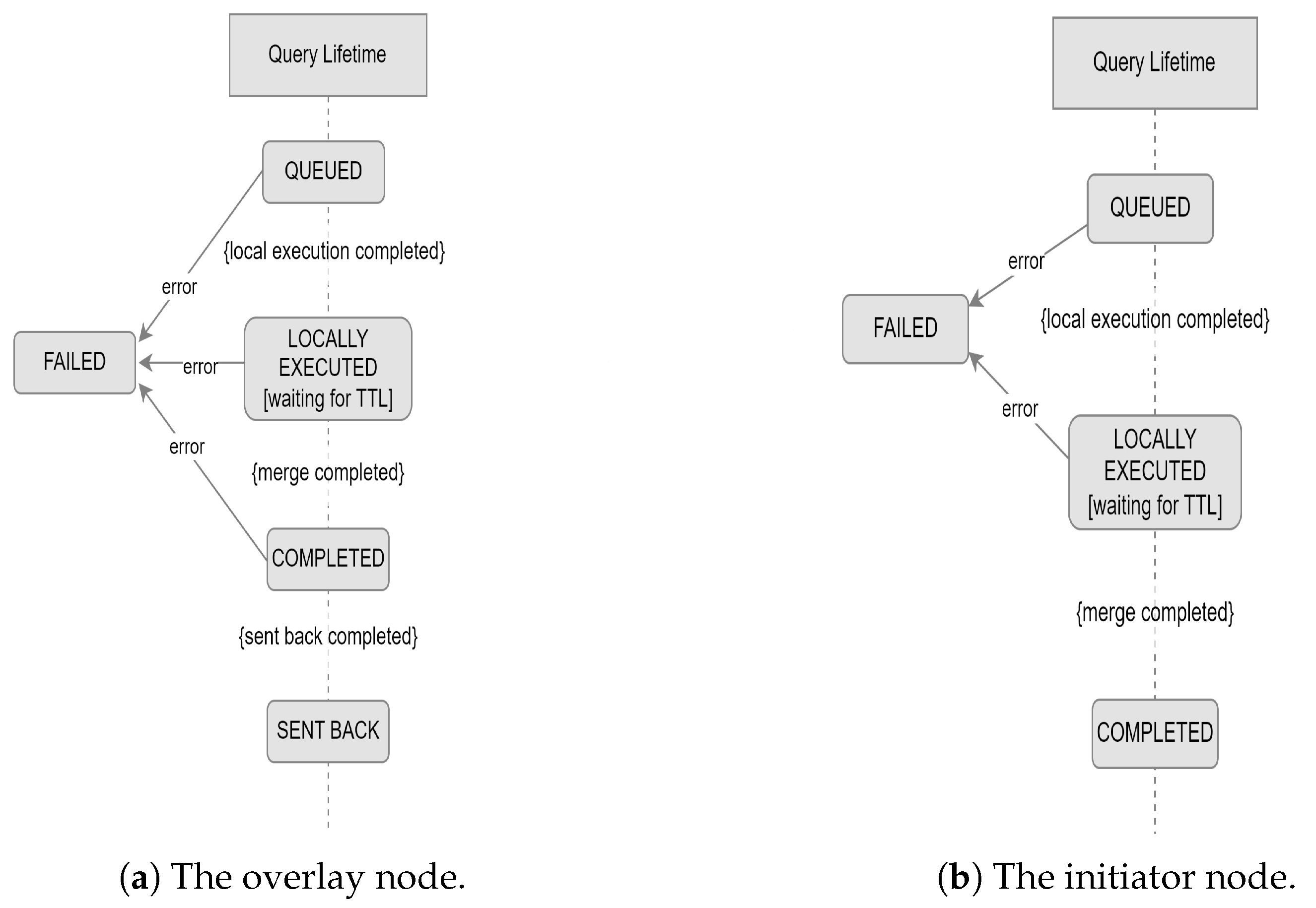

48], fetching results from G-IDSS is based on a “best effort” approach, given the potentially large number of distributed servers. Considering other factors that may affect an overlay, querying with a TTL of 3, for instance, will not always return the same number of records, even with a constant number of peers.

4.3.3. Other Querying Support

G-IDSS also supports running local queries, i.e., queries that are not intended to be broadcast in the overlay. This allows exclusively fetching data from a single peer, without necessarily fetching it from other peers. Additionally, all operations that require modifications to the graph data are limited to local data repositories, as it would not be reasonable to allow a peer to modify another peer’s datasets. To run local queries, a client must submit a query with either -l or -local flag. With the current release, we do not necessarily need to submit a TTL, as it is intended to control query propagation and dictate how long a client can wait before receiving the results.

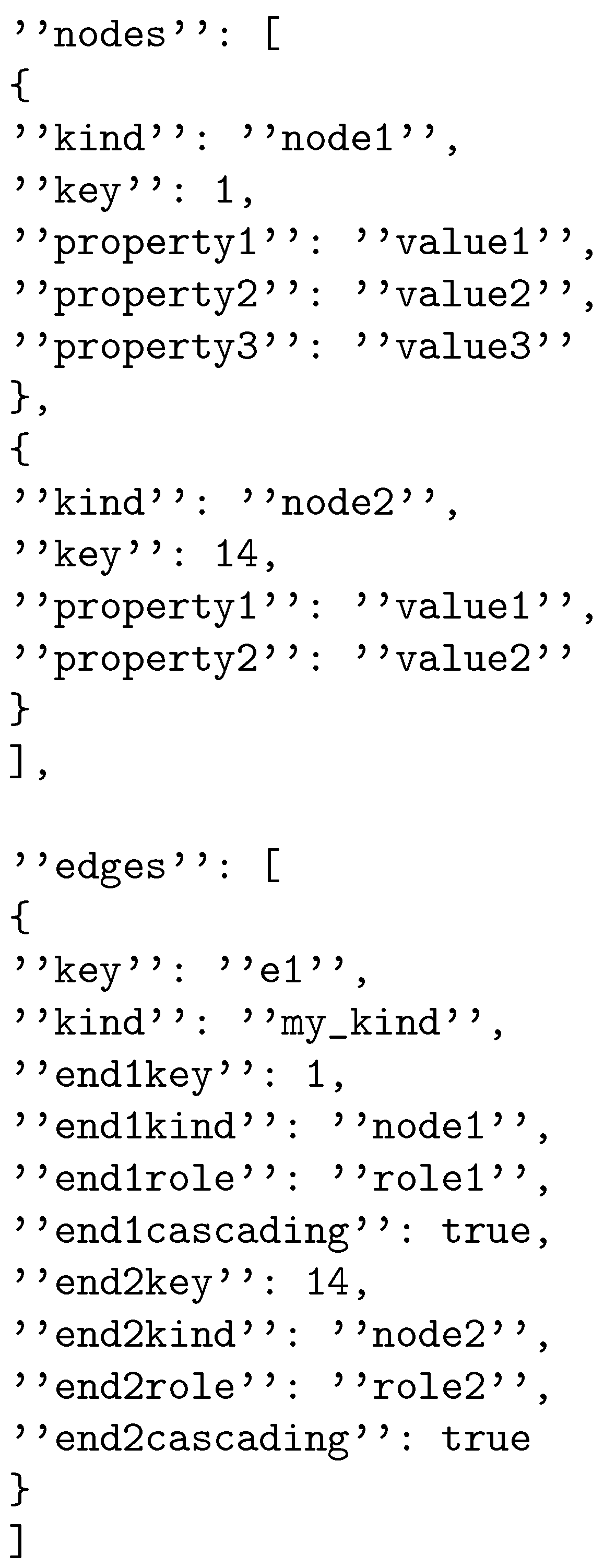

EQL does not inherently support data modification queries; however, EliasDB provides built-in ECAL functions for data modification, which can be executed as EliasDB graph manager operations or transactions. These functions are StoreNode(), which adds a node; RemoveNode(), which removes a node; and UpdateNode(), which updates an existing node. G-IDSS uses custom-defined keywords to facilitate the utilisation of these functions.

To add graph nodes, G-IDSS uses the keyword add to indicate a query that requires adding a node. The query must adhere to the “add <kind> <key> [properties]” syntax. This can be run as add Client 14 client_name = “John Doe” contract_number = 7437643 power = 7575.

To update/modify a graph node, G-IDSS uses the update keyword to change the values of an attribute or property. For instance, updating the Client with key “14” to a different name, we run the following query: update Client 14 client_name=“John Rhobi”. Lastly, to delete a graph node, a client must use the delete keyword, which is followed by a graph kind and key in the following format: delete <kind> <key>”. For example, a sample query can be formulated as delete Client 14.

In adding and updating graph nodes, queries may include attributes/properties that were not initially available in the graph data model. This implies that, when fetching the entire dataset, some graph nodes may have nil properties in certain instances, unless the data is universally updated or initial data preprocessing is performed within G-IDSS.

The time spent in fetching the complete result set is not constant. It is affected by factors such as the network traffic, the number of concurrent operations a single server must handle, the size of the overlay network, etc. The TTL set has a high impact on the completeness of the results. A higher TTL value will always guarantee the completeness of results. In small networks and controlled overlays, TTL may not be relevant; however, in large networks or when querying a global-scale network, it becomes relevant. In this case, we also note that the type of queries submitted did not place a significant computational load compared to other conditions. However, query formulation remains an important consideration when large loads are expected.

4.4. G-IDSS Clients

To assess the scalability and reliability of G-IDSS in a multi-client scenario, an experiment was conducted in which multiple G-IDSS clients were connected to a network of 10 server peers, with each client establishing a connection to a distinct server. The experiment aimed to evaluate the system’s performance in terms of connection establishment and data querying, focusing on success rates and data querying. The setup deployed 10 server peers, each running as a separate process with a unique TCP port (/ip4/127.0.0.1/tcp/x), and they were instantiated the EliasDB graph database with synthetic data (10 client nodes and 100 consumption nodes). Ten clients were simulated, each executed as a separate process, connecting to a randomly assigned server peer via its multiaddress. The experiment comprised two phases: (1) connection establishment, where clients initiated libp2p streams to their respective servers, and (2) data querying, where each client submitted a mix of local and distributed queries. Metrics included connection success rate, query response time, query success rate, and amount of data retrieved.

4.4.1. Client Connectivity

The connection phase tested clients’ ability to establish libp2p streams to their assigned server peers using the host.NewStream function in idss_client.go. The launch of client peers was performed across a variety of computing nodes with G-IDSS. Each client was provided with the multiaddress of its target server, e.g., /ip4/127.0.0.1/tcp/port/p2p/peerID, and the connection success rate was measured as the percentage of successful stream establishments. Across all server and client peers, the connection success was 100%, with no failures attributed. However, in a large-scale setup, we anticipate some failures due to port conflicts or transient resource contention within the test environment. When this happens, G-IDSS will log it by log.Error(“Error opening stream”). Connection latency, which is measured from stream initiation to successful establishment using WLS, averaged 15 ms in local settings and 73 s on the global internet because the bootstrap process traverses the entire libp2p network. Resource utilisation also peaks as the number of peers increases. The high success rate and minimal latency validate the robustness of the libp2p-based connection mechanism, particularly the lightweight Noise protocol’s secure handshake and the DHT’s rapid peer resolution. However, limitations include potential port exhaustion when scaling beyond 700 peers in the WSL setup, as dynamic port allocation can encounter conflicts, and increased CPU contention with more concurrent clients, suggesting a need for multi-VM deployments in larger scenarios. This was not experienced in gridsurfer as we launched up to 1500 peers.

4.4.2. Data Querying

The data querying phase evaluated the system’s ability to handle concurrent queries from multiple clients. One-to-one client-server querying was smooth, and data retrieval was straightforward. Queries were sequentially executed per client, with results processed locally and globally, in a distributed fashion. The query success rate, defined as the number of queries returning correct results (verified against a baseline of graph nodes loaded), saw both local and distributed queries achieve near-100% success, with data completeness affected by the TTL value and the load submitted to the server peer.

Distributed queries had a slightly lower data-completeness success rate due to occasional timeouts under high concurrency. Result accuracy was confirmed by checking that all client nodes returned the correct results for the distributed query example (as each had 10 consumption connections). These rates demonstrate G-IDSS’s ability to manage concurrent multi-client queries by leveraging the P2P overlay and EliasDB’s efficiency.

The experiment and broader G-IDSS implementation revealed several limitations across the P2P overlay, database management, and data querying, particularly in the single-VM setup. The P2P overlay faced scalability constraints due to port exhaustion and resource contention, as dynamic port allocation risked conflicts when scaling, and CPU/memory contention increased with concurrent clients/peers, limiting the system testing to a moderate network size. The reliance on the loopback interface eliminated real-world network variability (e.g., packet loss and latency), necessitating emulation via multi-VM testing for realistic conditions. In real-world scenarios, an overlay can scale up even further because each peer has its own autonomy and computing resources, thereby alleviating the problem of resource contention that we experienced in testing.

Database management was constrained by EliasDB’s performance with large datasets; while efficient for small graphs, query latency could increase significantly with an increase in nodes, requiring indexing or caching optimisations. Furthermore, data querying suffered from distributed query timeouts under high concurrency, as TTL-based propagation struggled with simultaneous requests and distributed queries incurred higher latency due to the merging of results. The single-machine setup exacerbated these issues by concentrating resource demands, and the lack of fault tolerance mechanisms (e.g., query retry policies) reduced robustness in the face of peer failures. Although libp2p promises scalability up to a million peers, G-IDSS still needs to be tested in a large-scale scenario that includes diverse datasets and multiple machines to achieve production-ready scalability and reliability.