1. Introduction

Precision Agriculture (PA) has transformed the agricultural sector in recent decades by enabling the collection, analysis and application of spatial and temporal data for optimised crop management [

1]. Its main aims include increasing productivity in response to global population growth [

2], improving resource-use efficiency, promoting more sustainable agricultural practices and helping address the impacts of climate change [

3]. Within this broader framework, Precision Viticulture (PV) has emerged as a specific application of PA, focused on the detailed monitoring and evaluation of vine growing conditions and physiological responses [

4]. A central concept in PV is bioclimatic monitoring, understood as the systematic observation of soil, plant and atmospheric variables to support data-driven decisions. These data underpin applications such as irrigation scheduling, pest and disease management, canopy management and the computation of climatic indices [

5,

6].

Increasing climate variability makes real-time bioclimatic information particularly relevant for sustainable wine production and for mitigating climate-related risks [

7]. What matters is not only the external environmental conditions, but also how they affect vine physiology and soil dynamics. Temperature, humidity, solar radiation and precipitation drive phenological stages—from budburst and flowering to fruit set and ripening—as well as photosynthesis, transpiration, nutrient uptake and fruit-quality development. Moreover, rainfall and evapotranspiration control soil-moisture availability and, consequently, root activity and nutrient transport [

8]. In this context, the term mesoclimate refers to the local atmospheric conditions that shape vine growth and grape composition at the vineyard or site scale [

9].

Monitoring is therefore a prerequisite for all PV applications: without reliable data, neither precise irrigation control nor robust risk assessments are feasible. Sensors are the core technology that convert physical variables into electrical signals that can be processed by microcontrollers or data-loggers. Remote-sensing technologies, such as satellite or UAV imaging, are valuable for large-scale vineyard mapping [

10]. However ground-based systems are better suited to continuous, high-resolution measurements at plant and soil level, which is consistent with the low-cost, site-specific focus of this work. Data acquisition systems (DAS) implement four core functions: collecting, processing, storing and transmitting data [

11]. Their performance depends on adequate sensor interfacing (signal conditioning and protection), on the accuracy of measurements and on sampling and telemetry rates that capture plant–environment dynamics. Architectures should remain scalable and interoperable to represent site-specific variability and to accommodate heterogeneous sensors. Nevertheless, architectures can be adapted to better suit more field implementation contexts or operator needs.

Considering proximal sensing, four main PV application domains can be distinguished for a DAS: smart irrigation, smart fertilisation, pest and disease control and climatic-index monitoring [

5]. Each application may require different sensor sets, and a fully inclusive system would quickly become complex and expensive. Taking into account complexity, cost and applicability, air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and direction, precipitation, leaf wetness, soil water tension and soil temperature were identified as a minimal yet representative set of variables that remains useful across these domains, while preserving the low cost and simplicity required by small- and medium-sized winegrowers. Because these variables describe generic soil–plant–atmosphere processes, the same sensing set can also be reused in other PV contexts and similar perennial crops, with minor adjustments in sensor placement and decision thresholds:

Climatic indices are pivotal because climate events act on both soils and plants, shaping grape maturation, evapotranspiration, disease pressure, and precipitation-driven moisture availability during critical phenological periods [

12,

13,

14]. At the vineyard/site scale, these indices are typically derived from mesoclimate observations (on-site stations or quality-controlled interpolations) [

15,

16]. Microclimate modeling can downscale these site-scale (mesoclimate) observations from on-site stations to ≈10 m grids, enabling viticultural indices to be computed at vineyard-landscape resolutions [

17].

Air temperature and relative humidity exhibit strong spatial gradients across vineyards [

18], and viticultural practices, like leaf removal, modulate these variables with direct consequences for grape quality [

19]. Monitoring both parameters therefore supports mesoclimate-informed management.

For irrigation, assessing the soil moisture status is a widely used strategy to reduce vine water stress [

20]. While assessing plant water status is a viable solution [

21], soil matric potential offers a cost-effective, accurate, and easily integrated alternative for proximal monitoring [

5].

Soil temperature governs key soil–plant processes: it influences microbial biomass and organic-matter turnover [

22], affects grape composition (elevating sugars while reducing acids and anthocyanins) [

23], and informs water-availability dynamics in the root zone [

24]. It is thus relevant to both fertilization and irrigation decisions.

Leaf wetness is a critical disease-risk indicator for proximal sensing: beyond its agronomic benefits [

25], many pathogens require surface water films to germinate and infect the plants [

26]. Coupling leaf-wetness data with climatic variables supports timely prediction and detection of disease outbreaks.

The need for effective bioclimatic monitoring systems has sparked the development of many research and commercial solutions [

27]. Nevertheless, the majority of existing platforms are characterised by high hardware and subscription costs, non-negligible power consumption, demanding installation and maintenance requirements, or limited adaptability to different agricultural contexts [

28]. Recent reviews on precision viticulture and digital agriculture report that high upfront investment, limited digital skills, perceived complexity and mistrust of digital tools are major barriers to the adoption of precision technologies, particularly among small and medium-sized wine producers [

27,

28,

29]. These producers represent a substantial share of the wine sector in many regions, yet often lack access to affordable, easy-to-use monitoring systems tailored to their constraints [

29]. Furthermore, traditional communication infrastructure is frequently non-existent or severely limited because vineyards are mostly located in remote areas [

28]. In this context, long-range communication technologies such as LoRa (Long Range) and cellular protocols (GSM, 3G, 4G) offer promising options for efficient data transmission over large areas, provided that they are integrated into low-cost and easily deployable DAS architectures [

30].

Likewise, IoT (Internet-of-Things) has boosted advances in this area, with the adaptation of new and existing technology for agricultural and viticultural practices. Generally, IoT is defined as a network of physical devices featuring sensors, software, and connectivity, all of which collect and exchange data autonomously. In agriculture, this concept has been applied for various purposes [

31], overlapping with PV applications already described. All of these applications benefit from the implementation of sensors and their integration into networked systems, such as wireless sensor networks (WSNs) that distribute homogeneous or heterogeneous nodes across a field to capture spatial variability, as in [

32], where a WSN-based solution for soil moisture and temperature monitoring is deployed in farmland. Other local systems combine sensing, actuation and wireless communication in compact weather stations or nodes that perform a wide range of tasks, such as the IoT-based weather station proposed in [

33].

Reliable communication between sensor nodes and data aggregation platforms is critical in IoT vineyard deployments, which often span large, topographically variable, and remote areas far from power and population centers. There are more than 20 communication technologies that allow for wireless data exchanges between devices and platforms [

30], but for agricultural applications, several factors such as range, energy consumption, cost and infrastructure availability influence the choice of communication protocols.

Wi-Fi offers high throughput but short range and high energy use with infrastructure demands; cellular communication protocols provide wide-area coverage but incur ongoing costs and higher power draw; ZigBee and similar mesh network protocols suit short-range links, yet add routing complexity. In contrast, LPWAN, particularly LoRaWAN, operates in unlicensed ISM bands, delivers kilometer-scale links at very low power and supplies a network layer with device addressing, adaptive data rates, and security. Its star-of-stars topology allows end devices to send uplinks directly to any in-range gateway (no multi-hop), minimizing configuration and energy. Thus, after taking into consideration the advantages and disadvantages, its clear that LoRaWAN offers a suitable solution for simple implementation and adaptability to different contexts.

The literature reports diverse PV DAS architectures spanning simple to flexible designs and varying their hardware choices. For example, Ioannou et al. [

34] proposed a low-cost automatic weather station for agricultural applications, capable of measuring multiple meteorological variables and serving a local HTML dashboard; however, its architecture is mainly oriented to a standalone weather station and does not explicitly address vineyard-specific bioclimatic monitoring or long-range, low-power networking beyond the local deployment. Another example is the system proposed by Mokhtarzadeh et al. [

35], which proposed a broader, low-cost ESP32 system that acquires data from multiple parameters and serves a local HTML dashboard for data visualizations, demonstrating how to implement a low-cost attractive system but relying on Wi-Fi and plain-page visualization that raises infrastructure and security concerns. These and other PV DAS architectures illustrate a clear trend towards affordable, sensor-based monitoring solutions in viticulture. At a more general level, Garcia et al. [

36] provided an overview of IoT-based smart irrigation systems, showing how low-cost sensors, wireless communication technologies and cloud platforms can be combined to improve water-use efficiency in precision agriculture, and highlighting the growing relevance of LPWAN solutions, such as LoRaWAN, for large-scale deployments. In line with these trends, several works have explored LoRa and LoRaWAN in vineyard and woody-crop scenarios, either for monitoring plant water status or for optimising network deployment and coverage.

Stojanovic et al. [

37] presented a compact, battery-powered LoRaWAN node based on an ESP32 module with a DHT11 and a custom soil-moisture probe, transmitting data to a remote server and demonstrating the simplicity and affordability of LoRaWAN nodes, although with a very limited sensor set and no specific focus on vineyard bioclimatic monitoring. Dafonte et al. [

38] implemented a multi-node LoRa system for woody crops, where each node integrates air-temperature, humidity, duplicated soil-moisture and soil-temperature probes and a Watermark sensor; the nodes communicate via LoRa to a nearby gateway that forwards data through Wi-Fi/4G, providing an efficient low-power field layer but still relying on existing infrastructure for backhaul and focusing mainly on soil-water monitoring. Valente et al. [

39] developed a flexible low-cost LoRaWAN node with support for SDI-12 and other agro-environmental sensors, validating long-range, low-power telemetry and plug-and-play integration of commercial instruments, but using relatively expensive sensor suites and not targeting a compact, dedicated proximal station for vineyard bioclimatic monitoring or a fully characterised energy-autonomous platform. Building on this hardware, Valente et al. [

40] proposed a complete LoRaWAN IoT system for vine-water-status determination, combining soil–plant–atmosphere measurements under field conditions, with an emphasis on water-stress assessment and high-end instrumentation rather than on a low-cost, easily replicable DAS for small and medium producers. Brunel et al. [

41] mapped LoRa signal propagation in a vineyard, characterising received signal strength and signal-to-noise ratio as a function of distance and terrain and providing guidelines for reliable network design, but without proposing an integrated sensing station. Overall, these works confirm the suitability of LoRa and LoRaWAN for remote, energy-efficient monitoring in viticulture, while also revealing gaps in terms of truly low-cost sensor integration, reduced dependency on external communication infrastructure, explicit energy-autonomy characterisation and holistic bioclimatic monitoring.

Building on these PV DAS and LoRa/LoRaWAN developments, this work proposes a low-cost, energy-autonomous bioclimatic monitoring system for precision viticulture that can be adapted to broader precision viticulture, and consequently agriculture. Unlike previous solutions that mainly rely on generic development boards or, in the case of Valente et al. [

39], on a flexible LoRaWAN node conceived for commercial sensors, the proposed system is built around a dedicated low-cost printed circuit board (PCB) that natively integrates multiple soil–plant–atmosphere sensors in a compact proximal station, simplifying assembly, wiring and replication. An MCU board with an integrated LoRa transceiver provides a LoRaWAN link between the field node and a central server, while a small solar panel and a rechargeable battery ensure continuous outdoor operation with minimal maintenance. The system is validated in a commercial vineyard through a side-by-side comparison with an industrial Meter Group station, and its energy performance is characterised to assess the feasibility of near self-sufficient operation.

Beyond this, the proposed system provides an end-to-end, reproducible architecture that combines open LPWAN infrastructure and the mySense platform, explicitly targeting the cost, complexity and adaptability barriers that currently limit the adoption of bioclimatic monitoring systems by small- and medium-sized producers. Accordingly, this manuscript focuses on cost-driven system integration, deployment and quantitative validation, with the main contribution being practical implementation and field performance assessment rather than the introduction of new sensing principles or agronomic models.

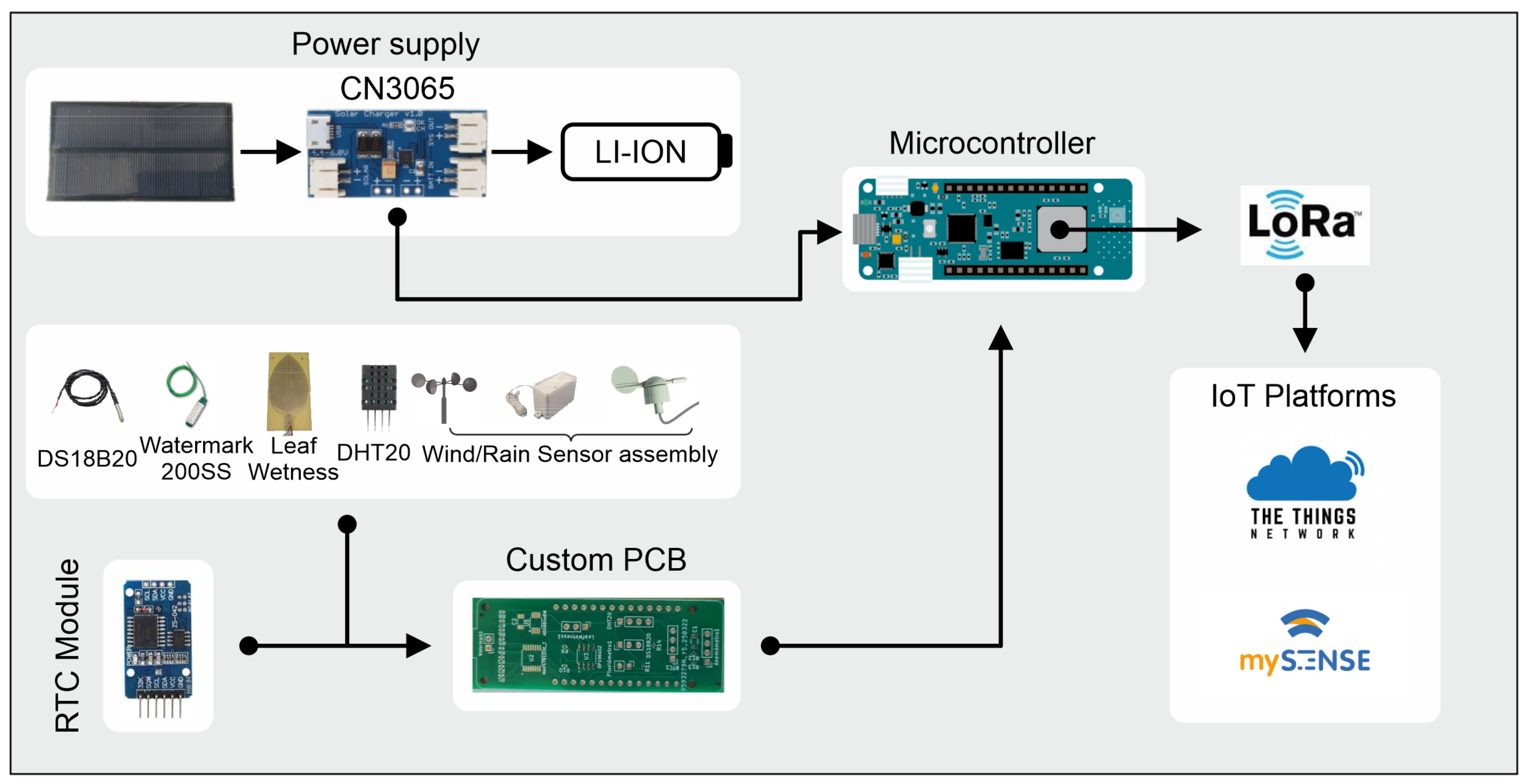

2. System Overview

Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed system, which integrates low-cost commercial sensors and a custom-built sensor, a low-power LoRaWAN-enabled microcontroller development board, a custom PCB which fuses the needed electronics and an autonomous solar power supply for continuous bioclimatic monitoring in vineyards. The component selection process was guided by trade-offs between cost and performance among commercially available components, with the aim of keeping the node cost in the range of a few hundred euros, while maintaining measurement quality suitable for the targeted precision viticulture use cases.

The chosen microcontroller development board for this project was an Arduino version that includes a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M0+ microcontroller and an integrated LoRa module Murata (Nagaokakyo, Kyoto, Japan) for long-range and low-power wireless communication, the Arduino MKR WAN 1310 (Arduino, Monza, Italy). The selection reflects a practical trade-off between cost, ease of LoRaWAN integration (via the Arduino ecosystem) and low-power operation, while enabling rapid prototyping through the Arduino IDE. Compared with approaches that require a separate MCU and external LoRa module or additional integration steps, the integrated board reduces component count and integration effort, supporting a cost-driven and reproducible design. Sensor data are collected at regular intervals and transmitted using the LoRaWAN protocol to a centralized gateway.

Environmental parameters such as wind speed, wind direction, and precipitation are measured using an Argent Data Systems 80422 weather sensor assembly (Argent Data Systems, Santa Maria, CA, USA), which integrates three passive sensors based on reed switches and magnetic triggers. The wind speed sensor (anemometer) and the rain gauge sensor work with external interrupts in a microcontroller. The wind direction sensor (anemoscope) generates a signal that when measured can be mapped to one of the 16 directions possible on a rose compass. These sensors interface the signals with an RJ-11 connector. The details of the sensors are presented in the manufacturer datasheet. Using a single integrated wind/rain assembly simplifies wiring and mechanical integration per node and improves deployment repeatability.

Air temperature and relative humidity are measured using a DHT20 (Aosong (Guangzhou) Electronics Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) digital sensor, which communicates with the Arduino MKR WAN 1310 through the I2C protocol. This sensor integrates both sensing elements and internal signal conditioning, facilitating reliable data retrieval via existing Arduino libraries, making it a reliable and easy implementable solution for these parameters. A multi-plate external shield is used to protect the sensor from solar radiation and precipitation, providing a more accurate measurement by blocking direct sunlight while allowing natural airflow. Its fully digital I2C interface minimizes analogue front-end circuitry and calibration effort on the custom PCB, reducing assembly complexity.

Leaf wetness is detected with a custom sensor mostly based on the design of the 237-L sensor (Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA), developed in [

42]. Using this sensor allows for reducing the cost of the final product, while remaining adequate for leaf-wetness detection in field operation. The sensor’s output varies in resistance depending on the presence of water bridging the electrode pattern. Given its low signal amplitude, the sensor output is routed through a non-inverting operational amplifier powered by the Arduino’s 3.3 V rail. This amplified signal is then read by the microcontroller’s 10-bit ADC. To reduce long-term degradation and oxidation of the electrodes, the sensor is powered using a digital output pin, activated only during measurement intervals for reducing the time it is powered. This approach reduces both material cost and long-term degradation risk, supporting a low-maintenance deployment.

Soil temperature is monitored using a DS18B20 digital sensor (Analog Devices, Wilmington, MA, USA), properly encapsulated to be used buried in the soil, which operates using the 1-Wire protocol. It provides a temperature measurement range of −55 °C to +125 °C with a typical accuracy of ±0.5 °C in the −10 °C to +85 °C range. The core of the DS18B20 is a silicon bandgap temperature sensor. This sensor was selected due to its low cost, digital interface (which reduces the need for analog signal conditioning) and ease of integration into outdoor IoT applications. Its waterproof encapsulation reduces packaging and installation effort for in-soil deployment without increasing system complexity.

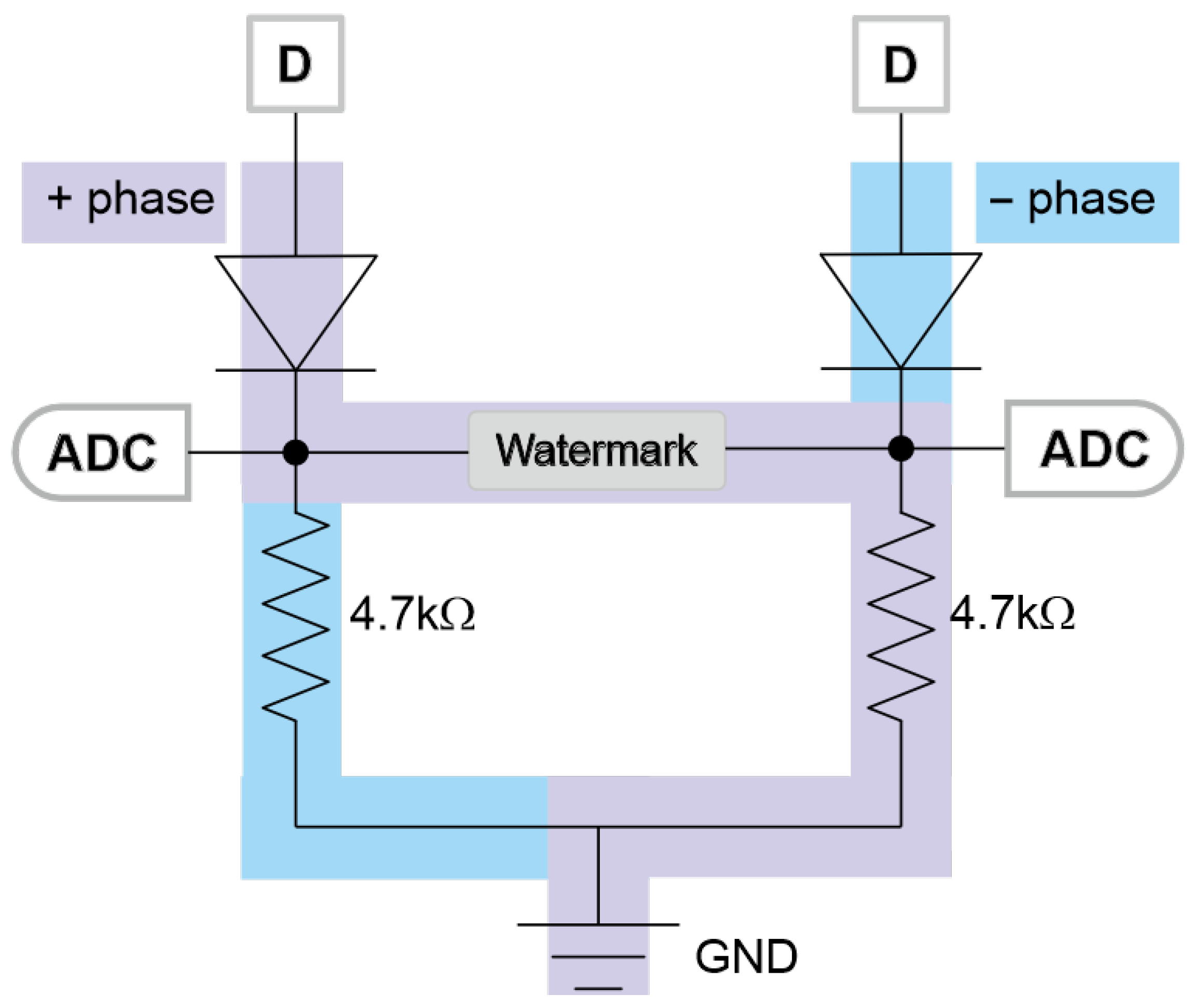

Soil moisture is measured using a Watermark 200SS sensor (Irrometer Company, Inc., Riverside, CA, USA), which relies on changes in electrical resistance within a porous matrix to estimate soil water tension.

The chosen method excites the sensor with simulated AC pulses, by rapidly reversing the applied polarity in short microcycles (“+” and “−” phases) while sampling the same sensing node in both phases. After that, it calculates the medium measured value, using that value with thermal compensation to convert resistance values into centibars. Studies show that the sensor can read values up to −600 cbs, but the recommended range, given by the manufacturer, is between 0 and −200 cbs, being that the sensor responds much slower to changes [

43]. This information show that the sensor will, most of the time, exceed the 200 cb value of the measurements, but being most trustworthy in the 0–200 cb range.

Because the electrodes are embedded in gypsum and the device behaves as an impedance with parasitic capacitance (not strictly ohmic), this alternating drive minimizes net DC at the electrodes and mitigates polarization/corrosion. A simple conditioning network with two diodes isolates the conduction path for each phase so that, at any instant, the reading corresponds only to the active leg of the resistive divider after a brief settling time. This method can be visually understood with

Figure 2. The polarity-switching excitation is implemented with simple PCB circuitry and timing control, avoiding specialised instrumentation while improving measurement robustness and sensor longevity.

Another essential component integrated in the system is an RTC clock, in our case a module based on a DS3231 (Analog Devices, USA) chip, to keep accurate time and generate periodic alarms to define the frequency of transmissions and data collection. Its built-in temperature-compensated crystal ensures minimal drift, and the alarm output lets the microcontroller wake up precisely (e.g., every minute) without busy-waiting. It also timestamps data collection and can be synchronized over the serial interface for manual clock updates. The DS3231 module was selected as a readily available commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) time base to schedule measurements and transmissions via periodic alarms/interrupts, ensuring accurate timing while avoiding continuous polling.

After deciding and testing the functioning of the previous presented components, it was time to think about how to implement them in a fully operable system. Regarding this, a dedicated PCB was custom designed and then manufactured by a specialized company. The design was shaped for the PCB to act as a shield for the Arduino microcontroller board. Adopting this PCB offers clear advantages over bread and protoboards: stable and repeatable connections, a compact layout with improved routing and noise immunity and mechanical robustness to vibration and thermal cycling. Moreover, the layout and design facilitate scalability, leaving open paths and pins which can be later used if needed. These characteristics are central to the standardization of this system for small- and medium-scale producers. At a unit manufacturing cost of 13.37 €, the custom PCB is a key enabler of repeatable assembly and straightforward replication in a cost-driven design.

In order for the system to operate autonomously, it was necessary to have a continuous power supply that would guarantee energy for the system to function correctly. With this in mind, and still trying to minimize costs, a mini 6 V 150 mA solar panel was purchased, providing a maximum power of 0.9 W. Its estimated energy conversion efficiency, under normal test conditions (1000 W/m2 of irradiance), is between 15 and 18%. The interface between solar panel and battery is made through a solar charger module based on a CN3065 (several manufacturers in the world) chip. The chosen battery was a rechargeable lithium one with 3.7 V and 2200 mAh, which means that for a system with an output of 100 mA, it can work for approximately 22 h. Using COTS power components reduces integration effort while enabling continuous outdoor operation with minimal maintenance.

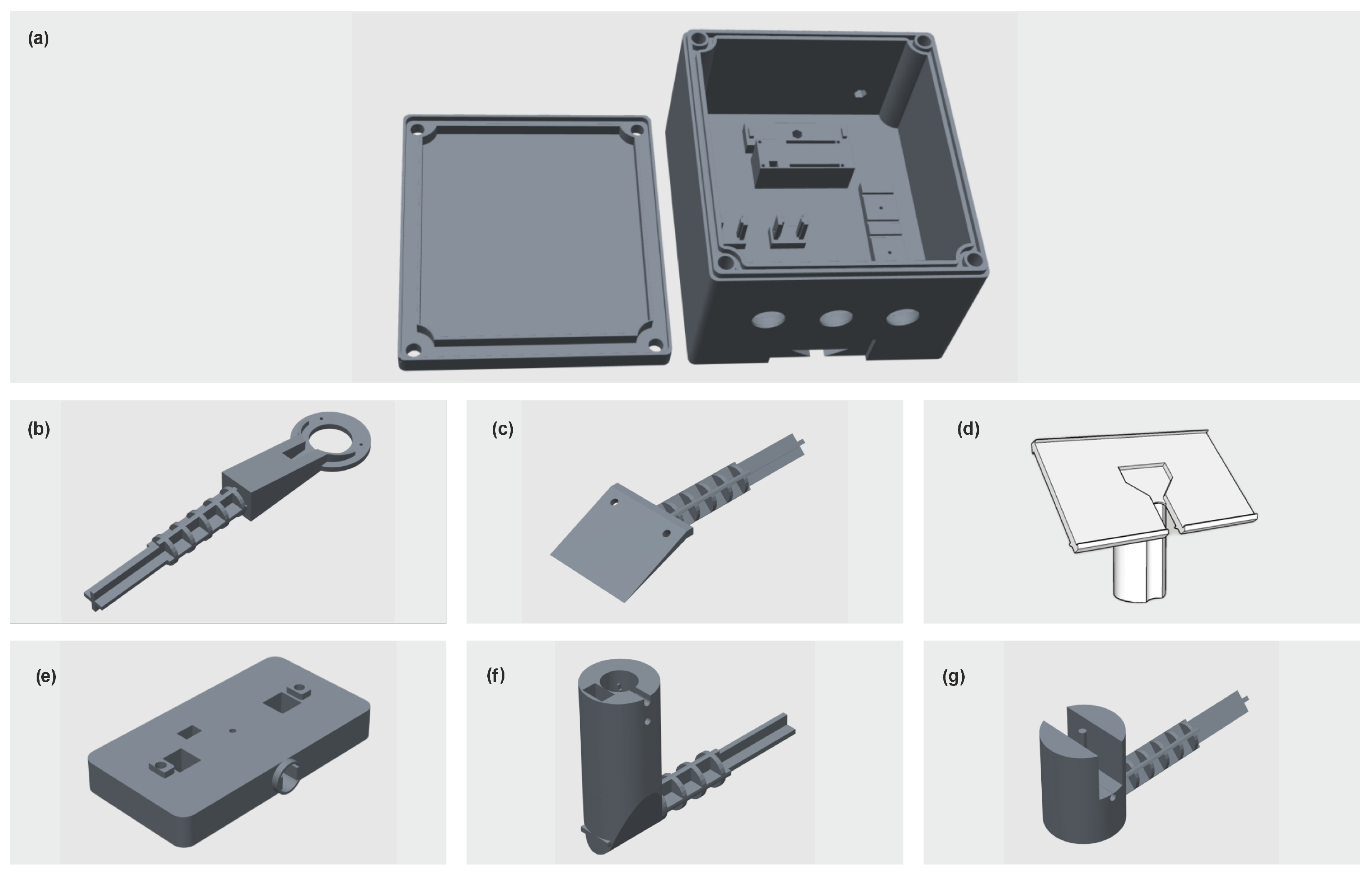

Having in mind that the system needed an external structure capable of being installed in a remote vineyard, a box and supports were needed so all the components could be accommodated. For this purpose, 3D printed parts were acknowledged as a low-cost and practical solution, guaranteeing the most important characteristics: adaptability, structural resistance to extreme climate events, and component suitability. In this way, five sensor supports, a solar panel support, and a box were printed in UTAD, using a Bambu Lab H2D 3D printer and ABS for the filament material. The printed parts can be seen in

Figure 3. Additive manufacturing avoids custom tooling and enables rapid adaptation of mounts and enclosure geometry to site-specific vineyard layouts while keeping the electronics and PCB unchanged.

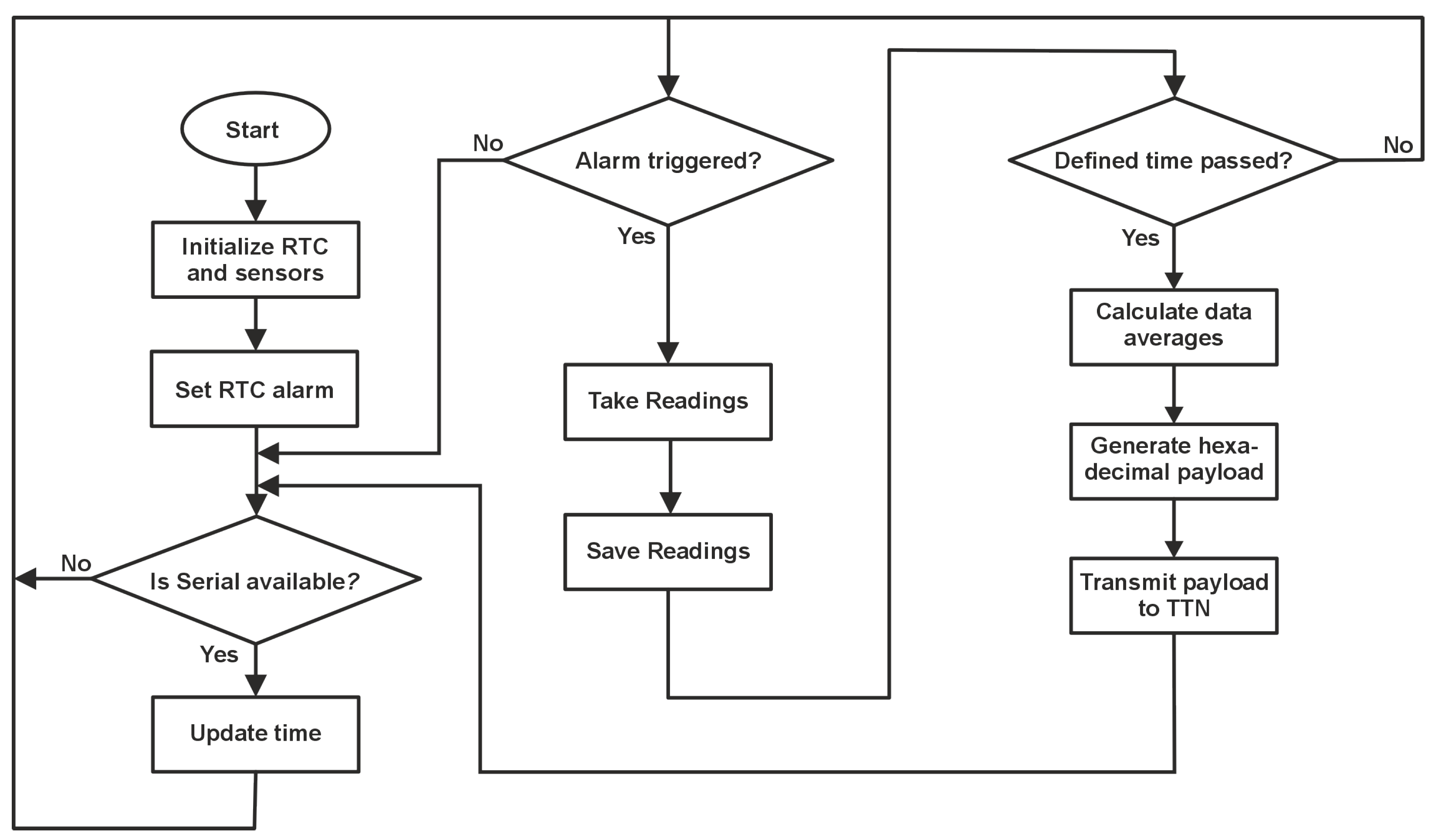

After selecting all components, firmware was developed to coordinate three stages: data collection, data preparation and lastly data transmission. Accordingly,

Figure 4 represents the firmware flow, which operates in the following manner: after powering up the microcontroller, it initializes the real-time clock and the sensors, then programs a periodic RTC alarm. The RTC-driven scheduling and 15-min cycle reduces radio activity and processing overhead while maintaining a time resolution suitable for the targeted applications. Every time the alarm fires, the code takes and stores samples from the sensors. Independently, it checks whether the defined collection interval has elapsed: when it has, the firmware computes averages of the stored readings, builds a hexadecimal encoded payload (including the channel-mask) and sends it over LoRa to TTN, clearing its buffers, and starting the next cycle.

Figure 5 shows the developed and installed field prototype, using a wooden vineyard post to ensure fixation, although it could be installed without it.

Before going to the data analysis, it is important to reflect on the cost of the developed prototype, since a low-cost product was one of the aims for the system. As so,

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide a compact and transparent breakdown of the per-node cost and the main price drivers, which is essential for reproducibility and cost transparency. The Vendor (example) column is retained even when certain parts were supplied by the university, offering equivalent sources for search and reproducibility.

As the table shows, the total cost for this station goes for around €260. Several mechanical items (posts, arms, metal clamps, and brackets) were supplied by the lab from previous projects, so their prices are indicative only. Unit prices are indicative procurement/reference values collected between November 2024 and February 2025 and may vary with supplier, VAT and shipping; USD prices were converted to EUR using the exchange rate at the time of collection. The total cost is not fixed: structural parts, mounts, and cabling can be substituted, and equivalent components may be sourced from alternative suppliers (including online marketplaces), potentially affecting both cost and durability. Overall, the station delivers its intended functionality at a low per-node cost, which can be further reduced through bulk purchasing or local sourcing.

The data gathered from the sensors are sent to a platform to be stored and analyzed. The mySense platform [

44], developed in UTAD, was chosen to smooth this process, as it is agriculture-oriented and easy for data access and visualization. This IoT platform is designed in a 4-layer architecture, which has been studied in the cybersecurity field [

45], showing how well-developed it is. Studies like [

46] show how IoT devices have been implemented with this platform, strengthening how well suited, for agricultural practices support, the platform is. Since the mySense platform isn’t a LoRaWAN Network Server (LNS), a dedicated LNS is needed to handle security, validation and decodification of LoRaWAN data packages. For this purpose, the The Things Network (TTN) was the chosen platform.

The field node operates as a LoRaWAN Class A end-device in the EU868 band, using Over-the-air-activation (OTAA) to join The Things Network (TTN). During the vineyard deployment, the node transmitted one unconfirmed uplink every 15 min on application port 3, with a compact hexadecimal payload whose maximum size is 24 bytes (4 bytes for the channel mask plus up to ten 2 byte channels). The data rate was managed by the network server using Adaptive Data Rate (ADR) with the default MKRWAN (Arduino library for microcontroller development board) and TTN settings for the EU868 band, ensuring reliable long-range communication while respecting regional duty-cycle constraints.

Specifically, the collected data is first packaged in a hexadecimal payload compatible with LoRaWAN: a 4 byte mask (32 bits) indicates which channels the data is sent on, followed by 16 bit values (big-endian, signed) for each channel present. The order results from the active bits in the mask. Each channel has a scaling factor applied in the TTN decoder, producing a JSON string with the fields already in physical units.

Figure 6 visually summarises this process.

Using a decoding function (Payload formatter) in TTN allows the data to be converted to a compatible format (JSON) for mySense. After that, data is sent to mySense via an HTTP Webhook. In the mySense Application Server, messages are received with a timestamp, node ID, and metadata (channel/sensor type), and are persisted in the time-series database for visualisation and analysis [

44].

3. Results and Discussions

After testing and preparing the node in the laboratory, the prototype was deployed in an actual vineyard, to evaluate its behaviour under real field conditions. Because the Li-ion battery is recharged by a small solar panel, the installation site had to ensure good exposure to direct sunlight and avoid persistent shading, which would reduce the effective daily charging time. The station was therefore installed on the property of the Mateus Palace/Casa de Mateus Foundation, in the parish of Mateus (Vila Real, Portugal), at WGS84 coordinates 41.2968° N, 7.7124° W (

Figure 7) [

47]. The site includes vineyards in production and an active winery (dating back to the 16th century) [

48], allowing direct observation of the cultural cycle and viticultural practices.

The Mateus Palace is located on the edge of the Douro Demarcated Region, at an altitude of about 500 m. In addition, the property hosts phytosanitary protection trials in a real-world context: as part of the UVineSafe project (CITAB/UTAD), UV-C treatments are being tested in a commercial vineyard owned by the Casa de Mateus Foundation with the aim of reducing the use of plant protection products by 30–50% [

49,

50,

51]. This context reinforces the relevance of the site for bioclimatic monitoring and decision-support studies. To validate the measurements, the prototype was installed next to a commercial Meter Group station (USA), which integrates factory-calibrated, higher-cost sensors from the same manufacturer.

The system operated continuously for 14 days, between 14 and 28 August 2025, with one acquisition and one LoRaWAN uplink every 15 min, that resulted in 1309 successful uplinks out of 1345, with no parameters values missing in each uplink. Overall, the time series show temporal and inter-sensor consistency, with no prolonged outages that would compromise daily mesoclimate analysis. The longest gap without records was 2 h 15 min, with the remaining gaps were short and showed no consistent temporal pattern, suggesting sporadic non-systemic failures. For precipitation and soil-matric-potential analyses, it was necessary to extend the analysed period: the first 14 days contained no rainfall events and the soil was already dry, preventing a meaningful assessment of rain-driven dynamics. The station therefore remained in operation until suitable events occurred, extending the observation window until 3 September 2025. For precipitation-related performance metrics, we focus on the paired timestamps within rainfall-event windows to reflect the intermittent, event-based nature of the signal.

The system was then evaluated in five main components, reflecting the following 5 subsections: Sensor data quality, discussing agronomic value for decision-making support, communications reliability and scalability, energy autonomy and prototype structural assessment and also in a cost-performance comparison with commercial and other existing solutions.

3.1. Sensor Data Quality

Sensor data quality was assessed by comparing the prototype readings with those of the co-located Meter Group station using paired 15-min records over the deployment period. Because data gaps and quality screening did not occur simultaneously in the two systems, the effective overlap window (and thus

N) differs across variables. Although the developed station produced 1309 complete uplinks over the 14-day deployment, the time series and agreement metrics reported in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and

Table 3 are computed from the paired valid overlap for each variable, resulting in

in several cases. For soil matric potential and wind direction, no direct comparison was possible because the reference station did not provide reliable measurements for the corresponding variables. All agreement metrics were computed from paired timestamps only (complete-case analysis), and no imputation was performed. To quantify uncertainty while accounting for temporal autocorrelation, 95% confidence intervals for the mean bias were estimated using a moving block bootstrap over the paired differences (developed minus reference), with block lengths defined in

Table 3. A bias is considered statistically different from zero when its 95% CI excludes zero.

is reported as the squared Pearson correlation coefficient computed over paired samples.

For air temperature and relative humidity, the time series closely follow those of the reference station (

Figure 8a,b), reproducing diurnal and nocturnal cycles and short-term events. A small negative systematic offset is observed in both variables: the mean bias is −0.79 °C for air temperature and −1.99% for relative humidity, with 95% CIs that exclude zero (

Table 3). Diurnal and nocturnal cycles are well reproduced and short-term events, such as the advection of moister air masses, are captured in both temperature and humidity. These results indicate that, despite low-cost sensing, the prototype provides measurement quality compatible with mesoclimate monitoring and decision support under the tested field conditions.

Soil temperature was measured at approximately 25 cm depth. Its temporal evolution is consistent with the reference station (

Figure 8c), with similar trends and amplitude. The mean bias is −0.70 °C with a narrow 95% CI that excludes zero, and the RMSE is 0.71 °C (

Table 3), which is within the range expected for proximal soil-temperature measurements, considering differences in exact burial depth, soil structure and local thermal properties.

For precipitation, the timing of rainfall events is coherent between stations and the recorded dynamics are consistent with the accompanying changes in air temperature and relative humidity (

Figure 8d). The mean bias is negligible (−0.01 mm) with a 95% CI that includes zero, and the RMSE is small (0.08 mm), although

is moderate (0.57), reflecting the intermittent, event-driven nature of rainfall at 15-min resolution (

Table 3). Because point-wise correlation is not fully representative for intermittent signals, we also examined agreement at the event scale by grouping consecutive non-zero reference records into rainfall events and comparing event timing and accumulated amounts over the corresponding windows. The developed gauge reproduces the main rainfall events visible in

Figure 8d with comparable timing, while differences in event magnitude are attributable to sensor design (collector diameter, bucket volume) and firmware, as well as to relative siting and short response delays. These effects are consistent with known intensity-dependent biases and undercatch in tipping-bucket rain gauges [

52,

53].

Regarding wind, the temporal evolution of wind speed shows similar dynamics in both stations, with coincident peaks during more intense episodes (

Figure 9a). The prototype exhibits a positive bias of 4.18 km/h with a 95% CI that excludes zero, and an RMSE of 5.81 km/h, with

(

Table 3). The higher variability of peak values in the developed station is explained by the firmware of the cup anemometer, which counts rotations in a short 2 s window and reports an almost instantaneous value, closer to gust speed, whereas the reference station applies temporal averaging, because it uses a ultrasonic type of anemometer. This behaviour is in line with the known sensitivity of cup anemometers to turbulence and averaging interval [

54,

55]. Wind direction is reported by the prototype as integer codes from 0 (north) to 15 (north-northwest) (

Figure 9b), with no failures obtaining the readings, showing proper functioning of the sensor and the firmware that acquires the data.

The leaf-wetness sensor correctly identifies periods with wet or moist leaf surfaces, which coincide with high relative humidity, low wind speed and, occasionally, precipitation (

Figure 9c). The prototype shows a mean positive offset of 0.37 in the normalised signal, with a 95% CI that excludes zero, and a comparatively low

(0.12), which is expected given the bounded and quasi-binary nature of the variable and the different calibration procedures used: the reference sensor is factory-calibrated, whereas the prototype relies on field calibration (

Table 3). To better reflect practical use, we therefore assessed wet/dry agreement by thresholding the normalised signals and comparing the timing of wetness episodes. Despite differences in absolute level and sensitivity, the onset and duration of the main wetness episodes are consistent between sensors in

Figure 9c, supporting the use of the developed sensor as input for disease-risk models when combined with temperature and humidity. This behaviour is consistent with the literature, which reports that leaf-wetness measurements are highly sensitive to sensor design, mounting height, orientation and exposure, and that different instruments may yield distinct absolute values even under the same conditions [

56,

57].

Finally, the soil matric potential (Watermark) measurements shown in

Figure 9d correspond to the developed station only (no reliable reference measurements were available) and reflect the dry conditions typical of late summer/early autumn, with tensions often close to the upper operating range of the sensor (

Figure 9d). Following rainfall events, a rapid decrease in matric potential is observed, followed by a gradual return towards pre-event values, in line with soil-moisture depletion by evapotranspiration. This behaviour is consistent with published evaluations of Watermark 200SS sensors, which report reliable performance in the 0–200 cb range but slower response and increased uncertainty at very dry conditions [

20,

43,

58]. These results confirm that the sensor is suitable for tracking trends in soil-water status and for supporting irrigation or controlled-deficit strategies, even if extreme dry-end values should be interpreted with some caution.

3.2. Agronomic Interpretation and Decision-Support Value

This subsection interprets the bioclimatic measurements in terms of agronomic decision support. Using the data obtained from the test window (14–28 August),

Table 4 summarises the daily mesoclimate, reporting extremes of air temperature and relative humidity, rainfall, mean wind speed and vapour pressure deficit (VPD). The aim is to characterise the environmental regime under which the node operated and to illustrate how the monitored variables can inform irrigation strategies, disease-risk management and, more broadly, within-season decisions in precision viticulture.

As shown in

Table 4, daily

reached

40.2 °C (day 14) and

dropped to

10.4 °C (day 28), evidencing a wide diurnal range. VPD spanned

0.59–2.68 kPa, with

high evaporative demand on days

14–17 and

23 (VPD ≥ 1.5 kPa). Mean wind speeds were

moderate–strong (∼5.7–12.5 m/s), favouring rapid leaf-surface drying, yet nightly

up to ∼90–95% indicates potential dew windows. With zero rainfall, soil-moisture dynamics are dominated by evapotranspiration, consistent with elevated Watermark tensions and only gradual overnight relief.

During the test period, the vines were in the veraison–harvest stage of their phenological cycle. In this phase, the target is typically a moderate water deficit that concentrates sugars and aroma compounds without arresting ripening, in line with regulated-deficit irrigation strategies reported for grapevine [

59,

60]. Accordingly, the combined analysis of air temperature, VPD and soil matric potential supports several concrete decisions: (i) on high-demand days (e.g., 14–17 and 23 August, VPD ≥ 1.5 kPa), soil-water status should be monitored more closely and short maintenance irrigations can be applied if tensions exceed the vineyard’s target band, to avoid excessive shrivel; (ii) under lower-demand days (e.g., 27–28 August), gentle recovery irrigations can be scheduled to preserve acidity and avoid must dilution; and (iii) the absence of rainfall during the period confirms that soil-moisture dynamics were dominated by evapotranspiration, consistent with the elevated Watermark tensions and their only partial overnight relief.

For disease management, the joint behaviour of relative humidity, wind speed and leaf wetness identifies potential infection windows. Nights with

above 90–95% and positive leaf-wetness readings, followed by slow drying under low wind speed, correspond to conditions favourable to Botrytis and other fungal diseases, and can be used to flag periods in which protective treatments should be prioritised on subsequent dry, calm mornings [

61,

62,

63]. Conversely, the predominance of dry, windy days during the test window indicates generally lower infection pressure. This allows for a reduction in the number of treatments and the associated costs and environmental impact, provided that wetness episodes are still tracked to avoid missing critical events. Beyond Botrytis, the same combination of temperature, relative humidity and leaf wetness can be used as input to empirical or mechanistic models for downy and powdery mildew risk, which rely on thresholds of wetness duration and temperature bands to estimate infection events. In this sense, the station supplies the minimum bioclimatic information needed to drive standard grapevine disease-warning models without requiring additional instrumentation [

61,

62,

63].

In addition to irrigation and disease control, the monitored variables support other PV applications such as canopy-management decisions (e.g., adjusting leaf removal according to microclimate measurements) and the computation of thermal indices that help to schedule harvest and compare vintages at the plot scale. Together, these examples show how the monitored variables and derived indices (e.g., VPD) translate into concrete recommendations for irrigation timing and disease-risk management, instead of remaining as raw sensor readings.

3.3. Communications Reliability and Scalability

The vineyard deployment also allows a first quantitative assessment of the LoRaWAN link. Over the 14-day window between 14 and 28 August 2025, with one unconfirmed uplink scheduled every 15 min, the node successfully delivered 1309 out of 1345 expected messages, corresponding to a packet delivery ratio (PDR) of 97.32%. The longest gap in the time series was 2 h 15 min; the remaining missing records were isolated and showed no clear association with a specific time of day or weather condition, suggesting sporadic non-systematic losses (e.g., transient fading, interference or temporary backhaul issues) rather than persistent link failures. For comparison, the co-located Meter Group station achieved a very similar data coverage (97.11%) over the same period, indicating that the proposed system attains reliability levels comparable to a commercial reference under the same field conditions.

In the adopted configuration, the node operates as a Class A LoRaWAN device in the EU868 band, using OTAA for network access, adaptive data rate (ADR) and unconfirmed uplinks. With one payload of up to 24 bytes every 15 min, the application-layer duty cycle of the node remains well below 0.02%, even for conservative spreading-factor choices. This is more than one order of magnitude under the 1% duty-cycle limit defined for the main EU868 sub-bands and is consistent with operating points recommended in LoRaWAN scalability studies, where tens to a few hundreds of devices per gateway can be supported at similar reporting intervals in rural monitoring networks without saturating the medium [

64,

65,

66]. The exclusive use of unconfirmed uplinks further reduces downlink load and avoids the well-documented impact of acknowledgements on network capacity in dense deployments [

67].

Scalability is also supported at the system level. On the device side, the custom PCB and firmware expose all eight sensor channels through a fixed payload mask, allowing additional nodes with identical or reduced sensor sets to be replicated without redesign. On the back-end side, the LoRaWAN star-of-stars architecture and the mySense platform naturally accommodate multi-node deployments: each station is mapped to a distinct object identifier, while the same TTN decoder and webhook configuration are reused to ingest data streams from multiple field nodes [

44]. For small and medium-sized vineyards, this enables single-station deployments for mesoclimate characterisation or sparse multi-station layouts (e.g., a few nodes per estate) to sample within-vineyard variability, with a single community or private gateway covering multiple producers.

Overall, the observed PDR in the single-node deployment, together with the low application-level duty cycle and the LoRaWAN-based architecture, indicate that the proposed system is compatible with reliable and scalable operation in typical vineyard scenarios. A dedicated multi-node field trial was beyond the scope of this work but is a natural next step to quantify collision rates and coverage margins as the number of deployed stations increases.

3.4. Energetic Profile Characterisation and Structural Assessment

To characterise the energy profile of the node, a dedicated measurement setup based on a Texas Instruments INA226 current–shunt and power monitor was used. The INA226 was inserted in a high-side shunt configuration between the Li-ion battery and the node’s power input and controlled by an Arduino Uno via an I2C interface. A microSD card interface logged the INA226 readings (bus voltage, shunt voltage, current and power) at 1 Hz during continuous operation. From these measurements, three main operating states of the 15-min duty cycle were identified: idle, sensor acquisition and LoRaWAN transmission. The corresponding average current, average power and fraction of time spent in each state were computed.

Figure 10 summarises the resulting energy behaviour: panel (a) shows the battery-voltage trace over a representative 14-day vineyard deployment, and panel (b) shows the power profile of a single 15-min duty cycle, where the one-minute acquisitions and the final LoRaWAN transmission spike are clearly visible.

The INA226 logs yielded mean currents of 26.136 mA in idle, 27.505 mA during sensor acquisition and 55.715 mA during LoRaWAN transmission. With a mean bus voltage of approximately 3.97 V (which decreases slightly for higher currents), these measurements correspond to average powers of ≈104 mW in idle, ≈109 mW in sensor acquisition and ≈210 mW during transmission. The node spends approximately 92.9% of the 15-min cycle in idle, 6.7% performing sensor data acquisition and 0.44% transmitting via LoRaWAN. The resulting time-weighted average power is

which corresponds to a daily energy consumption of

To relate this measured consumption to the solar subsystem, we consider the 3.7 V, 2200 mAh Li-ion battery (≈

Wh) and the 6 V, 150 mA photovoltaic panel (0.9 W). The effective daily energy harvested by the solar panel can be written in terms of the number of equivalent full-sun hours

and a lumped efficiency factor

that accounts for controller, cabling, temperature and battery-charging losses:

For the study region, in northern Portugal, long-term solar resource assessments indicate annual mean global horizontal irradiation values corresponding to about 4–5 equivalent peak-sun hours per day [

68,

69], with higher values during summer. In small stand-alone PV systems, it is common to assume that these losses reduce the usable energy at the battery to roughly half of the panel’s nominal STC power over a day. Taking

and

h as a representative summer value, the expected daily energy effectively available to the node is therefore

which is of the same order of magnitude as the measured consumption

Wh/day. A lower effective efficiency would lead to a small daily deficit that can be buffered by the 8.14 Wh battery, whereas higher efficiencies or longer sun hours would produce a modest surplus.

Consistently with this simple energy budget, the measured battery-voltage trace in

Figure 10a shows daily charge–discharge cycles between approximately 3.78 V and 4.2 V, with no long-term downward drift over the 14-day deployment. This behaviour indicates that, under the irradiance conditions experienced during the test period (mid-August), the energy harvested from the panel was sufficient to balance the node consumption. Together with the power trace in

Figure 10b, these results support the conclusion that the current design is compatible with near self-sufficient operation under summer irradiance in the study region. A more detailed assessment of year-round autonomy would require long-term joint monitoring of load current and incident irradiance, but the measurements and simple energy budget presented here are consistent with the intended low-maintenance, solar-powered operation of the node.

A structural prototype analysis, after prototype development tests and the field deployment test period of the system, revealed that the 3D printed box, sensor supports and solar panel support withstood thermal and meteorological variations without significant loosening and degradation. However, incremental improvements were identified:

better UV resilience (more suitable materials and/or addition of stabilizers and coatings);

sealing and breathing space (better condensation management and cable glands);

geometric robustness of the supports (thicknesses and radii of agreement) to reduce local stresses and wear due to thermal cycles.

These improvements should improve the structure of the system, so it can stay operating for a very long time and allow for easier maintenance.

3.5. Cost-Performance Comparison and Discussion

After presenting and discussing the main results and their main aspects, it is also important to assess and discuss the cost–performance of the system, in comparison with other similar solutions. In this way, it can be provided an integrated view of hardware cost and measurement performance. The material cost of the developed station was estimated from the bills of materials in

Table 1 and

Table 2, resulting in approximately 260 €. For direct comparison, the co-located reference system is based on commercial hardware from METER Group, which, with a configuration of sensors comparable to those in the developed station, uses a compact ATMOS-22 weather station, a leaf-wetness sensor, a soil-temperature sensor, a soil-matric-potential sensor and a ZL6 datalogger. Based on price lists from European distributors [

70] and the official METER store, the reference configuration (ATMOS-22, PHYTOS-31, TEROS-21 and a dedicated RT-1 soil-temperature sensor) has an aggregate cost of approximately 1900 €. Adding the ZL6 datalogger (837 €) and the annual subscription to ZENTRA Cloud (about 220 €/year), the total cost of ownership in the first year is close to 3000 €, which contrasts with the 260 € hardware cost of the developed station, free from annual subscription fees. Even restricting the comparison to the eight bioclimatic variables monitored by both systems, the cost per measured variable is on the order of a few tens of euros for the prototype, versus a few hundred euros for the commercial station.

Beyond this specific reference configuration, many commercial bioclimatic and precision-viticulture platforms follow a similar pattern: proprietary multi-sensor stations, vendor-specific dataloggers and cloud services that require recurring subscription fees, often with limited access to raw data and restricted options for sensor expansionX [

27,

28,

29]. In contrast, the proposed station is built from off-the-shelf components, exposes all raw measurements at the application layer and can be integrated with open IoT platforms such as mySense [

44], thereby reducing vendor lock-in and facilitating replication, repair and adaptation by small- and medium-sized producers.

A further practical aspect is network coverage. In areas without existing public LoRaWAN infrastructure, installing a gateway increases the initial investment; however, this cost can be shared by several users or absorbed by the implementing entity. Addressing coverage constraints is therefore an integral part of enabling wider adoption of this type of system by small- and medium-scale producers.

From a deployment-at-scale perspective, the proposed station provides proximal measurements representative of local canopy/soil–atmosphere conditions. Therefore, large-area monitoring is achieved by replicating low-cost nodes across management zones (e.g., irrigation blocks or topographic units) and sharing network infrastructure, rather than assuming a fixed sensing radius per station. In practice, the required number of nodes is an integer and depends on how many zones need independent decision support: a homogeneous 4 ha block may be monitored with one node, whereas a 40 ha vineyard may require, for example, 4 nodes (one per 10 ha) or 8 nodes (one per 5 ha) if higher spatial resolution is needed.

In terms of cost, node hardware scales approximately with the number of deployed stations: the upfront node investment is about

, where

is the per-node hardware cost (approximately 260 € as built,

Table 1 and

Table 2). For example, one node corresponds to about 260 €, and four nodes to about 1040 € (excluding any gateway cost). Gateway requirements are not directly determined by vineyard area in hectares, but by radio coverage conditions, which are typically expressed over distances (km) and depend on antenna height, terrain and line-of-sight. As a reference for scale, 100 ha correspond to 1 km

2, so a single gateway footprint of a few kilometres can cover many tens to hundreds of hectares in favourable conditions. Consequently, when public/community LoRaWAN coverage is available, the marginal cost of adding nodes is mostly the per-node hardware; when coverage is not available, a dedicated gateway adds a one-time infrastructure cost that can be shared across all nodes in the deployment (and potentially across neighbouring users), and may require more than one gateway only for very large areas or complex topography.

Interpreting these cost figures together with the data quality results provides a clearer view of the system’s cost–performance balance. The developed station achieves RMSE values below 1.5 °C for air temperature and below 5% for relative humidity, with coefficients of determination above 0.96 (

Table 3), and soil-temperature errors of about 0.7 °C. Precipitation timing and magnitude are consistent with the reference within the expected limits for tipping-bucket gauges, and wind speed shows the expected positive bias associated with the different sensing and averaging strategies. Leaf-wetness and soil-matric-potential measurements reproduce the onset and duration of wet and dry periods, providing agronomically useful trends despite the use of low-cost sensors. In addition, the energy analysis shows that the node can operate close to energy self-sufficiency with the chosen panel and battery, while maintaining this level of data quality.

When compared with other open-hardware solutions, a representative benchmark is the SEnviro platform [

71,

72]. The vineyard-oriented SEnviro node measures eight meteorological variables (air and soil temperature, air and soil humidity, atmospheric pressure, rainfall, wind speed and wind direction), costs about 256.45 € per unit and, in a 140-day deployment with 10-min sampling, achieved data-delivery success rates between 91.96% and 98.75% across five nodes. The proposed station operates in a similar cost range (approximately 260 € per node) but with a different emphasis: it uses LoRaWAN instead of 3G/Wi-Fi, integrates a bioclimatic sensor set that also includes leaf wetness and soil matric potential, and has its measurement performance quantitatively benchmarked against an industrial PV station (bias, MAE, RMSE and

in

Table 3). In addition, communication reliability is evaluated side by side with the commercial system (packet-delivery ratio over the same period), with both systems having a proper energy consumption characterisation. Overall, these comparisons indicate that the proposed system offers a more favourable cost–performance balance, while remaining versatile for different agricultural and viticultural applications.

When focusing specifically on LoRa/LoRaWAN-based systems, the proposed station also occupies a distinct position in terms of sensing scope, validation and cost. Stojanovic et al. [

37] reported a material cost below 200 € and kilometre-scale communication, but without an explicit energy budget or an extended multi-variable DAS. Dafonte et al. [

38] implemented a multi-node LoRa field layer for woody crops, but the focus remained on soil-water-status monitoring and does not extend to a holistic bioclimatic station or a cost-per-variable analysis. Valente et al. [

39,

40] thoroughly characterised communication coverage and plant-water-stress indicators, yet the sensing end relied on high-end commercial instruments, without a detailed breakdown of hardware cost or cost per monitored variable.

In the work of Stojanovic et al. [

37], the LoRaWAN node monitors a small set of variables (air temperature, relative humidity and soil moisture) and is validated mainly in terms of connectivity and basic time-series plausibility, without reporting quantitative error metrics (e.g., bias, MAE, RMSE) against a commercial reference or a detailed analysis of current consumption in each operating state. Dafonte et al. [

38] provide laboratory calibration and field trends for their low-cost soil sensors within a multi-node LoRa network, but performance is mainly expressed through calibration curves and qualitative soil-water dynamics, rather than through a full set of field error statistics and an explicit energy-autonomy budget. Valente et al. [

39,

40] demonstrate continuous LoRaWAN communication without data loss during vine–water–status campaigns and use soil–plant–atmosphere measurements to support irrigation decisions, but do not publish a complete hardware cost breakdown or per-variable sensor errors. Altogether, these systems confirm the technical suitability of LoRa/LoRaWAN for irrigation and water-status monitoring, but the balance between hardware cost, quantitatively validated measurement accuracy and long-term autonomy is either only partially characterised or oriented to higher-end instrumentation, whereas the present work explicitly targets that balance for all characteristics of a low-cost proximal bioclimatic station.

In contrast, the present system combines a deliberately low-cost sensor set with a dedicated PCB, providing sufficient flexibility for deployment in different agricultural contexts. The selected variables and sensors are not specific to a single vineyard, but are applicable to multiple viticultural and agricultural applications, which increases the usefulness of each node per euro invested.

From a data-management perspective, the use of an open LoRaWAN stack and the mySense platform ensures that measurements are stored as raw time series with standardised metadata and can be accessed through documented APIs [

44], in contrast to many commercial ecosystems that primarily expose processed indicators via vendor-specific dashboards.

The side-by-side quantitative validation against an industrial PV station demonstrates that non–factory-calibrated low-cost sensors intended for field deployment can still achieve agronomically acceptable accuracy for bioclimatic monitoring. The explicit energy-autonomy assessment identifies the margins for improving long-term, low-maintenance operation, while confirming that the current design is close to self-sufficient for the high irradiance conditions in spring and summer. In addition, the measured packet-delivery ratio shows that the LoRaWAN link provides sufficient reliability for near real-time monitoring without systematic loss of information relevant for decision support.

Taken together, these results indicate that it is not necessary to rely exclusively on high-cost bioclimatic stations equipped with specialised industrial-grade sensors to obtain data of sufficient quality for irrigation management and disease-risk assessment. Instead, the proposed station occupies an intermediate design point in the current solution space, achieving a favourable balance between hardware cost and the number and type of sensors when compared both to generic low-cost IoT nodes with limited sensing capabilities and to commercial multi-sensor platforms. Overall, the proposed design combines (i) a low-cost yet agronomically meaningful sensor set for soil–plant–atmosphere monitoring, (ii) a quantified assessment of data quality, energy autonomy and communication reliability, and (iii) a cost–performance analysis against both an industrial PV station and representative low-cost alternatives.

Despite these favourable cost–performance results, some constraints remain and point to opportunities for further optimisations. First, it would be of particular interest to test the system over longer periods and across different seasons, in order to better assess and refine energy-consumption optimisations. A slightly larger photovoltaic panel or an adaptive duty cycle would increase the safety margin for long-term autonomous operation, with negligible impact on the final hardware cost. Second, the analysis presented here focuses on hardware acquisition cost and does not yet quantify life-cycle costs such as long-term sensor drift or enclosure ageing, which will be relevant for multi-year deployments. Third, additional actuator hardware and firmware for different applications could be tested to further characterise how the system behaves when adapted to other contexts (e.g., large-scale vineyards or different crops).

Overall, these elements provide a more complete cost–performance picture than in other comparable systems, showing that it is possible to balance hardware cost, data quality, communication reliability and energy autonomy in a way that is compatible with widespread adoption by small- and medium-scale producers.

4. Conclusions and Final Remarks

In a 14-day deployment in a commercial vineyard, co-located with an industrial Meter Group station, the prototype showed good agreement for the main variables. Air and soil temperatures exhibited RMSE values below 1.4 °C and relative humidity an RMSE of about 4.5%, with coefficients of determination above 0.96. Precipitation timing and magnitude were consistent with the reference station within the expected uncertainty of tipping-bucket gauges, and wind speed followed the same dynamics, with a positive bias explained by the different sensing and averaging strategies. Leaf wetness reproduced the onset and duration of the main wet/dry episodes observed in the co-located reference sensor, supporting its use for disease-risk models. Soil matric potential (Watermark) exhibited coherent rain-driven and dry-down dynamics, providing trend-based decision support for irrigation even in the absence of reliable reference measurements.

The LoRaWAN link achieved a packet-delivery ratio of 97.32% over the test window, comparable to the data coverage of the industrial station, while operating with an application-level duty cycle below 0.02%. The measured power profile yielded an average consumption of approximately 0.105 W (about 2.5 Wh/day). Combined with a simple energy-budget analysis and the observed battery-voltage trace, these results indicate that the present power subsystem is compatible with near self-sufficient operation under summer irradiance in the study region.

From a cost perspective, the hardware for the developed node amounts to roughly 260 €, dominated by sensors and mechanical components, whereas an equivalent Meter Group configuration plus cloud subscription exceeds 3000 € in the first year of operation. Even when restricting the comparison to the eight common bioclimatic variables, the cost per measured variable is therefore reduced from a few hundred to a few tens of euros. Relative to other open-hardware and LoRa/LoRaWAN-based systems, the proposed station combines a holistic sensor set, explicit quantitative validation against an industrial reference, an energy-autonomy assessment and an end-to-end cost–performance analysis framed by agronomic use cases. At scale, the initial hardware cost can be expressed as a function of deployment density (nodes/ha), yielding a first-order cost per hectare of approximately plus a shared gateway term when dedicated infrastructure is needed, which supports practical large-area deployments without assuming a fixed sensing radius per station.

The agronomic interpretation of the measurements illustrates how the monitored variables and derived indices, such as vapour-pressure deficit and soil matric potential, can support irrigation scheduling and disease-risk management during the veraison–harvest period. High-demand days and wetness episodes can be objectively identified, enabling maintenance irrigations and targeted phytosanitary treatments, while dry, windy conditions suggest windows for reducing interventions without increasing risk.

Despite these favourable results, some limitations remain. A longer-term, multi-season assessment is needed to characterise year-round energy autonomy, sensor drift and enclosure ageing, and to quantify performance under different climatic regimes. In addition, the cost of gateways in areas without public LoRaWAN coverage and the integration of actuators for closed-loop control deserve further study. The modular PCB and firmware already provide a basis for adapting the node to other perennial crops and for scaling to multi-node deployments.

Overall, by combining dedicated PCB-based integration of soil, plant and atmospheric sensing, solar-powered autonomous operation, and a LoRaWAN end-to-end data pipeline, the proposed station delivers a reproducible field node suitable for precision viticulture. Validated side-by-side against a commercial reference, it achieves agronomically useful monitoring at a material cost approximately one order of magnitude lower than a comparable commercial station, enabling scalable deployments by replicating low-cost nodes across management zones and sharing network infrastructure where available.