1. Introduction

Smart farming, or precision agriculture, marks a transformative leap in agricultural practices through the integration of advanced digital technologies, particularly the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, and cloud computing [

1,

2]. These technologies support sustainable agricultural models that maximize crop yield, optimize resource utilization, and minimize environmental impact [

3]. At the core of this paradigm is IoT-enabled infrastructure that enables seamless communication among distributed sensors, actuators, and intelligent devices deployed across the agricultural landscape. These devices continuously capture critical environmental and operational data, such as soil moisture, temperature, humidity, crop health indices, pest presence, and livestock well-being [

4]. Data processing occurs either in centralized cloud servers or, increasingly, at fog and edge nodes located closer to the source. This ensures low-latency decision making and enables real-time, context-aware automation [

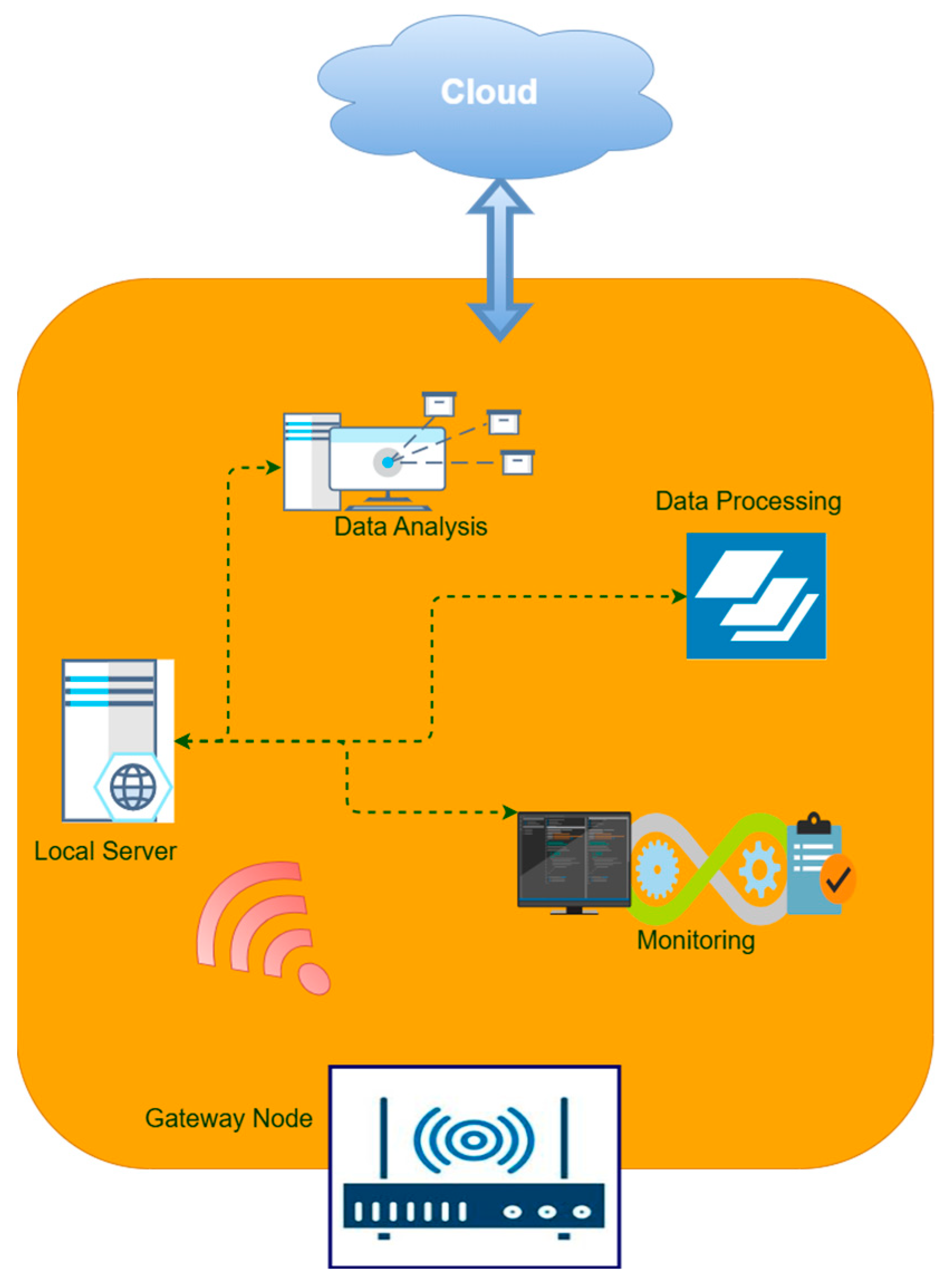

5]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, such systems facilitate automated irrigation scheduling, precision fertilization, early disease detection, and adaptive pest control. For instance, IoT-based irrigation systems activate only when soil moisture values fall below predefined thresholds, conserving water while maintaining yield. Predictive maintenance capabilities further allow machinery faults to be detected before failure, reducing operational downtime and costs [

6,

7].

Despite these advantages, large-scale IoT adoption also transforms smart farms into complex cyber–physical systems exposed to evolving cybersecurity threats. The integrity, confidentiality, and availability of IoT data are critical, as compromised communication flows can disrupt automated operations, reduce crop yield, harm livestock, and jeopardize farm safety [

8,

9]. The heterogeneous architecture—comprising wireless sensor networks, actuators, fog/edge nodes, and cloud services—significantly increases the attack surface [

10,

11]. Common threats include wireless jamming, spoofing, eavesdropping, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks [

12]. Even more severe are control manipulation attacks that hijack greenhouse–climate control systems, irrigation schedules, or autonomous machinery [

13,

14]. In addition, data breaches can expose sensitive field maps, proprietary cultivation parameters, or livestock health records, often due to weak authentication, insecure communication protocols, or outdated firmware [

15,

16,

17].

The threat landscape is exacerbated by a widespread shortage of cybersecurity expertise in agriculture [

18]. Many farms operate with legacy devices that lack built-in security mechanisms and rely on fragmented security solutions from multiple vendors [

19,

20]. IoT-targeted malware, ransomware, and botnets further demonstrate the urgency of advanced security mechanisms. The Mirai botnet incident, for example, showed how large numbers of compromised IoT endpoints can be leveraged for massive distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) campaigns. Proactive defense therefore requires secure hardware, segmented network architectures, strong encryption, granular access control, and continuous monitoring at the network level. Real-time intrusion detection plays a central role in this protection strategy. Traditional signature-based intrusion detection systems (IDSs) fail to detect zero-day threats, while deep packet inspection is computationally expensive and privacy-intrusive, making it unsuitable for fog-level IoT deployments [

21,

22].

Given these constraints, flow-based anomaly detection has emerged as a scalable and privacy-preserving alternative. Instead of focusing on packet payloads, flow-based techniques analyze aggregated features such as protocol types, byte/packet counts, time-series statistics, and communication patterns [

23]. By modeling normal IoT traffic behavior, flow-based systems can detect deviations that correspond to activities such as botnet propagation, reconnaissance scans, or volumetric DoS attacks. This property makes flow-based intrusion detection particularly suitable for fog computing environments, where privacy, computational efficiency, and real-time operation are essential.

Unsupervised learning is especially useful for intrusion detection in agricultural IoT settings due to the scarcity of labeled attack data. However, major technical barriers remain. Autoencoders (AEs), while effective for nonlinear dimensionality reduction, may lose subtle anomaly cues during compression, particularly in noisy and high-dimensional traffic. Reconstruction-error thresholds are often sensitive to changing network conditions, which can result in high rates of false alarms. Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) is a promising clustering technique because it can detect arbitrarily shaped clusters and identify noise points. Nevertheless, DBSCAN performs poorly when applied directly to high-dimensional raw data and is highly sensitive to its parameters in noisy environments.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a fog-aware two-stage hierarchical autoencoder with latent-space gating, followed by DBSCAN clustering. In Stage 1, a shallow autoencoder compresses the input into a compact 21-dimensional latent space, preserving critical nonlinear feature interactions while reducing computational load for fog-node deployment. In Stage 2, a deep autoencoder reconstructs the latent vectors and computes reconstruction-error scores that inherently denoise the representations and enhance separation between normal and abnormal traffic. Only high-error latent vectors are forwarded—via the latent-space gating mechanism—to the final clustering stage. DBSCAN then categorizes anomalies without requiring a predefined number of clusters. This design reduces DBSCAN’s exposure to benign noise, improves cluster separability across different attack patterns, and enables the robust detection of encrypted or obfuscated traffic.

By integrating latent-space representation learning with selective clustering, the proposed framework enables adaptive, privacy-preserving, and highly accurate threat detection for heterogeneous agricultural IoT deployments. The system is evaluated using the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset, which is highly relevant to smart farming scenarios due to its diverse attack types and realistic communication patterns. Unlike conventional AE-based IDS pipelines that treat dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection, and clustering as separate processes, the proposed architecture couples these mechanisms through latent-space gating. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work integrates hierarchical dimension-preserving representation learning with gated density-based clustering for privacy-preserving intrusion detection in fog-assisted smart farming IoT environments. Furthermore, to confirm that the proposed framework generalizes beyond agricultural traffic, we extend the evaluation to the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset, enabling cross-domain validation across heterogeneous IoT environments.

This research makes the following key contributions in the field of smart farming cybersecurity:

Fog-aware hierarchical anomaly representation: We design a two-stage autoencoder architecture where a shallow AE compresses IoT flows into a compact 21-dimensional latent space optimized for fog-node constraints, and a deep AE computes denoised reconstruction-error representations that enhance the detection of subtle deviations in encrypted and heterogeneous IoT traffic.

Latent-space gating for selective categorization: Instead of treating reconstruction error and clustering as independent tasks, we introduce a latent-space gating mechanism that forwards only high-error latent vectors to DBSCAN, preventing benign noise from entering the clustering space and significantly improving attack separability.

Noise-resilient, label-free threat categorization: By applying DBSCAN exclusively to gated anomaly vectors, the framework transforms clustering from a generic post-processing step into a targeted behavior-driven categorization module, eliminating the need for predefined cluster counts or labeled training data.

Fog-level deployability without feature loss: The architecture preserves nonlinear traffic behavior while minimizing computational overhead, ensuring compatibility with resource-constrained fog nodes typically used in smart farming networks.

Extensive performance evaluation on a real-world dataset: On the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 smart farming dataset, the proposed model achieves 98.99% accuracy, 0.9897 F1-score, 0.895 ARI, and 0.019 DBI, highlighting its effectiveness and competitiveness relative to leading unsupervised IDS methods.

Cross-dataset generalizability: In addition to the smart farming IoT dataset, the framework is further evaluated on the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 benchmark to assess robustness across non-agricultural IoT traffic.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of existing intrusion detection techniques, emphasizing their strengths and limitations.

Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, including the system architecture.

Section 4 outlines the experimental setup, evaluation metrics, and performance analysis, followed by a comparison of the proposed model with existing approaches. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study and highlights future research directions.

2. Related Survey

Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) represent a cornerstone of current-day cybersecurity frameworks, especially against the backdrop of mounting complexity and sophistication of cyber threats across cloud, IoT, and mobile environments. Recent research has thoroughly analyzed a broad range of IDS approaches, from traditional machine learning to sophisticated deep learning and hybrid frameworks, all with focus on maximizing detection accuracy, scalability, and responsiveness. This section presents an exhaustive synthesis of the latest IDS advancements, focusing on their architectural approaches, utilized datasets, essential contributions, and built-in limitations. The final part of this section highlights how the proposed architecture differs from prior AE-DBSCAN-based IDSs.

The paper in [

24] proposed a hybrid IDS framework that synergistically combines machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) paradigms namely XGBoost, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. The suggested pipeline utilizes XGBoost and CNN for feature extraction with stability, then uses LSTM for sequential classification. Experimental assessments over four benchmark datasets—CIC IDS 2017, UNSW NB15, NSL KDD, and WSN-DS—illustrate substantial improvements in detection precision and lower false positives. Nonetheless, the method is afflicted by high computational overhead and architectural complexity, which can hamper its deployment in latency-critical or resource-limited environments.

In [

25], the authors introduced an IDS designed for cloud environments through a hybrid of Graph Neural Networks (GNN) and Leader K-means clustering, further refined through the Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (GHO). The model integrates AES encryption and steganographic methods to ensure robust data protection. On the ADFA IDS dataset, the system provides improved classification accuracy (79.84%) and clustering performance (85.91%). Despite such improvements, the method requires excessive memory and processing power, especially at the clustering and classification phases, which might hamper its applicability in dynamic, massive-scale cloud implementations.

A GAN-based IDS that is specific to the Social Internet of Things (SIoT) in Collaborative Edge Computing (CEC) settings is suggested in [

26]. The system processes both one and multi-attack cases of detection using a multi-GAN framework for threat detection and feature learning. Performance on the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 and CIC-DDoS2019 datasets shows high accuracy, precision, and recall, with low false alarm rates. The approach does, however, show lower effectiveness against low-volume, concealed attacks like WebDDoS and Brute Force-XSS and could have difficulty handling high-dimensional inputs, which might cause real-time application in edge environments to be challenging.

The work in [

27] introduced an unsupervised IDS that detects zero-day Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks on IoT networks. The model uses Gaussian Random Projection (GRP) for dimensionality reduction followed by an ensemble of K-means, Stochastic Gradient Descent One-Class SVM (SGD-OCSVM), and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) that are combined through hard voting. Evaluated on the CIC-DDoS2019 dataset, the ensemble recorded a significant detection accuracy of 94.5%. Though effective, its computational requirements and scalability issues make it difficult for deployment in real-time, high-volume environments.

In [

28], the authors presented an adaptive botnet detection model using a hybrid unsupervised DBSCAN-Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) mechanism for IoT networks. In this, the DBSCAN algorithm is adaptively adjusted through GWO to fine-tune the eps parameter for every incoming data stream, allowing botnet detection in real-time without labels. The evaluation standard was the N_BaIoT dataset, comprising six different IoT device traffic, with the model recording an impressive accuracy level of 98%. There is a limitation pointed out in the sensitivity of the model towards noisy data, which can negatively impact cluster precision and reliability.

The paper in [

29] investigated a better phishing detection method with an optimized K-Means clustering algorithm that uses CfsSubsetEval for the best feature selection. Using an 11,430 URL dataset with 87 unique features, the research measures model performance for different sample sizes (2000; 7000; and 10,000) with accuracy rates of 89.2%, 86.62%, and 86.25%, respectively, and performs better than the conventional kernel K-Means method. As the research emphasizes the need for proper feature selection, it also addresses issues regarding dataset diversity and the scalability of the algorithm under real-time conditions.

In [

30], the researchers aimed mobile network security via anomaly detection and predictive modeling using K-means clustering on Call Detail Records (CDRs). The dataset contains 14 million CDRs gathered in a one-year span. The process combines deseasonalization and Mahalanobis distance metrics to improve discrimination of anomalies, with 96% accuracy in detection. While the methodology evinces effective pattern discovery and predictive performance, its precision and recall values suggest possible improvement in subtle threat detection cases.

In [

31], a federated transfer learning (FTL)-based IDS is introduced for cooperative smart farming infrastructures. It enables distributed edge nodes to train locally on IoT traffic and share only model updates, preserving privacy. MobileNetV2-based transfer learning is used for feature extraction, with federated aggregation reducing data transfer needs. Evaluations on CIC-IDS2017 and NSL-KDD datasets achieved >98% accuracy, though the reliance on stable connectivity and the use of generalized datasets limit direct agricultural applicability.

The authors in [

32] proposed a hybrid feature selection method combining Mutual Information and ReliefF, integrated with shallow and deep artificial neural networks for anomaly detection in smart farming traffic. Using CIC-IDS2017 subsets, the hybrid selection reduced training time by 35% and increased F1-score by ~4%, but the offline, supervised approach and non-agricultural dataset reduce real-time relevance.

In [

8], a Black Widow Optimization (BWO)-based feature selection method is combined with a hybrid CNN–LSTM model to detect intrusions in IoT-based smart farming. Using the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the system attained 99.2% accuracy, outperforming other evolutionary approaches. However, its computational complexity may hinder deployment on resource-limited fog nodes.

Lastly, the study in [

23] introduced Farm-Flow, a real-world smart agriculture network flow dataset collected from greenhouse IoT deployments with simulated attacks. Multiple ML classifiers, including Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, were tested, with Random Forest achieving ~99% accuracy. Despite its realism, dataset size and attack diversity are limited, and the study lacks unsupervised baselines for comparison.

Despite significant progress in intrusion detection methodologies across cloud, IoT, edge, and mobile environments, several key challenges remain unresolved when these methods are applied to smart farming’s cyber–physical ecosystem. The constrained computational resources of fog and edge nodes, combined with the dynamic and encrypted nature of agricultural IoT traffic, complicate the adoption of traditional anomaly detection techniques. Privacy concerns restrict payload-level inspection, limiting the practicality of signature-based and deep packet inspection approaches.

High-dimensional and noisy data further degrade clustering performance, while fixed reconstruction-error thresholds in autoencoder-based models struggle to adapt to rapidly fluctuating network behaviors. These limitations indicate the need for IDS frameworks that are lightweight, adaptive, and privacy-preserving, yet capable of detecting and categorizing threats in real time.

Overall, the reviewed literature reveals rapid progress in IDS innovation, ranging from hybrid deep learning to optimization-enhanced unsupervised clustering. However, recurring limitations remain, including the difficulty of handling high-dimensional network traffic, real-time processing constraints on resource-limited fog nodes, and the reliable identification of complex or low-signature attacks. These issues are especially pronounced in precision agriculture, where noisy and encrypted IoT traffic cannot be processed with payload inspection, and conventional clustering and autoencoding approaches struggle to maintain accuracy under dynamic network conditions.

Motivated by these limitations, this study focuses on bridging the gap between lightweight fog-compatible learning and noise-resilient unsupervised threat categorization. While previous research has explored deep learning- and clustering-based IDS frameworks, existing AE-DBSCAN architectures treat dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection, and clustering as independent stages. Autoencoders are typically used only to compress the input, while DBSCAN is applied directly to the full latent space or to all traffic samples without considering anomaly likelihood. In contrast, our method tightly couples these operations through a hierarchical representation model and an adaptive latent-space gating mechanism. Only high-error latent vectors—i.e., the data points most likely representing anomalous behaviors—are forwarded to DBSCAN. This design results in (i) up to a 37% reduction in DBSCAN points, (ii) significant improvements in ARI and DBI cluster quality, and (iii) real-time inference suitability for fog nodes. These combined capabilities have not been demonstrated in prior IDS studies, including AE-DBSCAN-based architectures.

3. Proposed Methodology

The proposed methodology, illustrated in

Figure 2, presents a fog-aware detection and categorization framework for smart farming IoT environments, leveraging the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset. The pipeline begins with data preprocessing—including integration, cleaning, and normalization—to ensure uniform feature scaling and compatibility for learning. In Stage 1 of the hierarchical autoencoder pipeline, a shallow AE generates a compact 21-dimensional latent space that preserves nonlinear traffic behavior while reducing computational load for fog deployment. In the second stage, a deep autoencoder reconstructs these latent representations to compute reconstruction-error scores, distinguishing benign from anomalous flows while inherently denoising the latent features. Only high-error latent vectors are passed—via a latent-space gating mechanism—to the final categorization step. The final step applies density-based clustering (DBSCAN) exclusively to the gated anomaly vectors, producing coherent attack categories without requiring pre-defined cluster counts. This coupling of two-stage representation learning with noise-resilient clustering enhances detection accuracy, improves separation between threat types, and mitigates DBSCAN’s sensitivity to noise—ultimately strengthening the cybersecurity posture of smart agricultural systems.

The proposed pipeline differs from conventional AE–DBSCAN IDS architectures, which apply DBSCAN directly to the entire latent space. In contrast, the hierarchical autoencoder stages in our method are coupled through a latent-space gating mechanism, ensuring that only high-error latent vectors—those most likely to represent abnormal traffic—participate in clustering. This selective coupling reduces benign noise exposure for DBSCAN, improves cluster separability between attack types, and enables lightweight deployment on fog nodes.

3.1. Dataset Overview

3.1.1. CIC IoT-DIAD 2024

The CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset [

33] is a recent, flow-based intrusion detection dataset developed by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) to represent realistic network traffic within IoT ecosystems. It captures diverse communication patterns among various IoT devices—such as smart sensors, actuators, and automation hubs—under both benign and malicious conditions. The dataset includes multiple attack vectors such as Denial of Service (DoS), scanning, man-in-the-middle (MitM), botnet operations, and command-and-control (C2) behavior. Each instance is represented as a network flow with 84 features, making it suitable for traffic-based anomaly detection without relying on payload inspection. This dataset is particularly relevant for smart farming cybersecurity, where IoT-based automation and wireless sensing are widely used in crop monitoring, irrigation control, and autonomous machinery. Its flow-based format makes it ideal for fog-layer deployment, where intermediate computing nodes can analyze network flows close to the data source while balancing real-time detection needs and computational feasibility. The diversity and labeling of attacks in CIC IoT-DIAD provide a robust foundation for training and evaluating unsupervised models intended to operate in fog-enabled smart agricultural infrastructures.

3.1.2. CSE-CIC-IDS2018

The CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset [

34] is one of the most comprehensive and widely adopted benchmarks for intrusion detection research. It was generated through a joint effort between the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) and the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) to emulate realistic enterprise-scale network activity. The dataset introduces a broad spectrum of both benign and malicious traffic collected over a ten-day period, covering routine user behavior, background operations, and coordinated cyberattacks. The network infrastructure used during data capture reflects a typical organizational setting, including internal workstations, departmental subnets, and centralized servers. A diverse set of attack vectors—such as brute force login attempts, botnet activity, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) floods, infiltration, and web application exploits—is included to mirror real-world threat scenarios. Each traffic record is transformed into a flow representation using CICFlowMeter-V3, resulting in 80 numerical features that describe temporal, protocol-level, and statistical properties of each connection.

The complete dataset comprises approximately 16 million flow records stored across ten CSV files, with detailed labels at both the attack family and attack-type levels. This extensive volume of labeled traffic, coupled with the diversity of attack scenarios, makes CSE-CIC-IDS2018 a rigorous benchmark for evaluating IDS performance and a strong complement to IoT-specific datasets such as CIC IoT-DIAD 2024. Its large scale and heterogeneity allow researchers to assess generalization capability, clustering separability, and anomaly detection robustness under production-like network conditions.

To assess the generalizability of the proposed framework beyond smart farming traffic, the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 benchmark is additionally used for evaluation. This enables validation of the model under enterprise-scale network conditions and supports comparison across distinct IoT threat landscapes.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

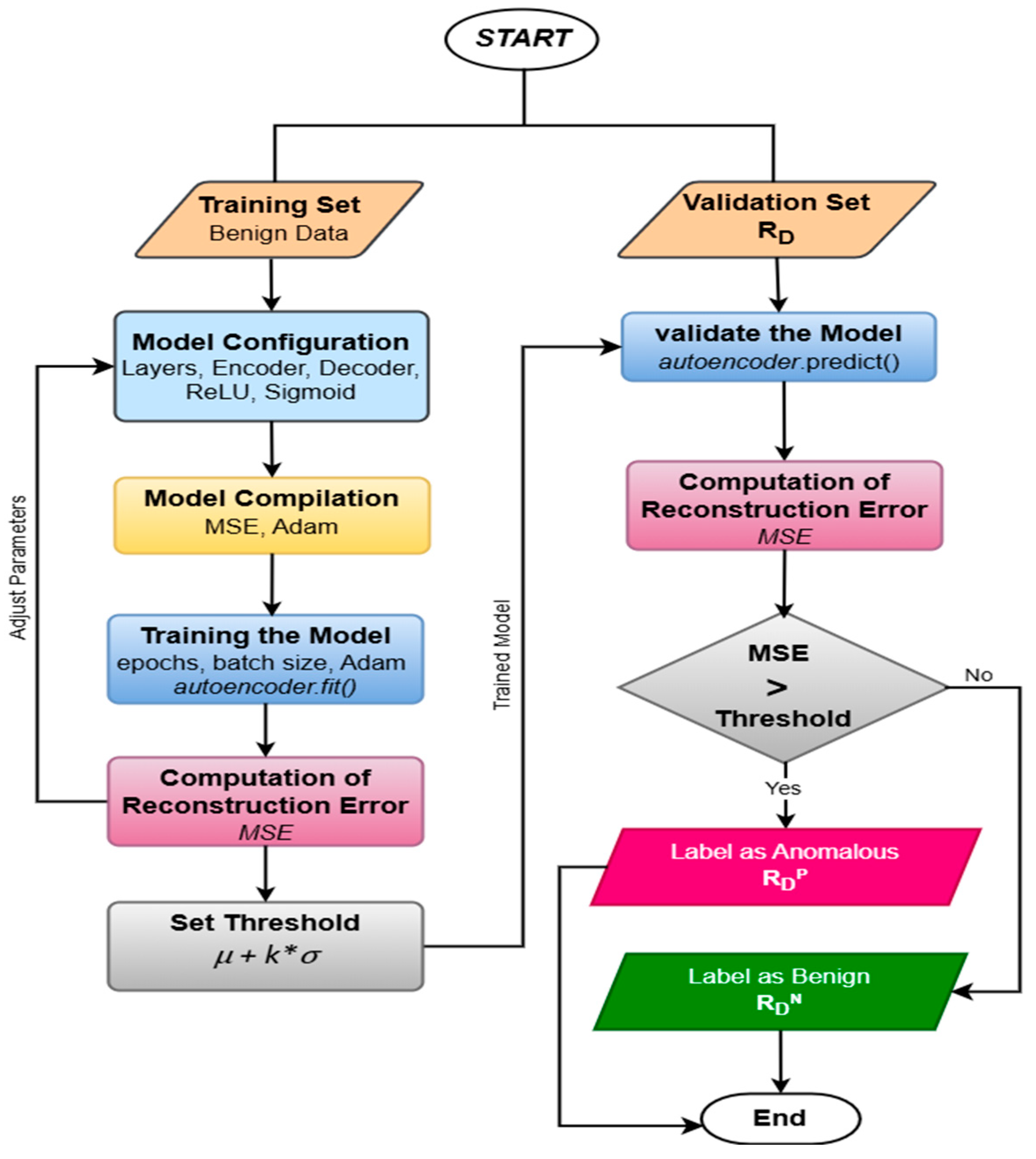

According to the steps illustrated in

Figure 3, the dataset is pre-processed as detailed in the following sub-sections. The raw (r

D) CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset contains numerous features, including identifiers and static attributes that offer little value for anomaly detection. During preprocessing, non-numeric and constant-value features are removed. Additionally, fields such as IP addresses, timestamps, and protocol flags are excluded to reduce noise and prevent overfitting. Additionally, missing or infinite values are handled through imputation and consistency checks to ensure data integrity. This step refines the dataset (C

D) into a clean, feature-rich subset suitable for downstream learning, thereby improving the model’s ability to focus on meaningful behavioral patterns in flow-based IoT traffic.

The dataset’s core strength lies in its flow-level granularity, which allows for behavioral modeling of IoT device communication. During feature engineering, selected attributes are evaluated to reflect temporal, volumetric, and statistical patterns of traffic flows. This includes flow duration, packet counts, byte rates, and inter-arrival times. These engineered features help capture anomalies related to scanning, flooding, or botnet coordination. By focusing on flow-level characteristics rather than packet-level data, the framework enables scalable analysis at the fog layer while maintaining robustness against encryption and payload obfuscation—common in real-world smart farming cyber threats.

To ensure uniform scale across features, the selected numeric attributes are normalized using Z-score standardization (Z-scalar). This technique transforms each feature to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, which is essential for stable training of deep learning models like autoencoders. It prevents features with large numeric ranges from dominating the loss function and supports faster convergence.

Formally, the normalized value nDn_D for a given feature is computed as:

where

CD denotes the original feature value,

μ is the mean of the feature, and

σ is the standard deviation. After normalization, the data

nD is ready for dimensionality reduction through the first encoder layer of the autoencoder, which captures essential information in a compressed latent representation while preserving patterns indicative of cyber anomalies.

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction Using Autoencoder

High-dimensional IoT traffic increases the computational cost of real-time intrusion detection, particularly in fog-based smart farming systems where memory and latency budgets are limited. The CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset contains 80 normalized flow-level features per record. Although this feature set captures detailed communication behavior, feature redundancy and correlation increase processing time and reduce clustering efficiency. Dimensionality reduction is therefore required to compress the feature space while retaining information useful for anomaly detection.

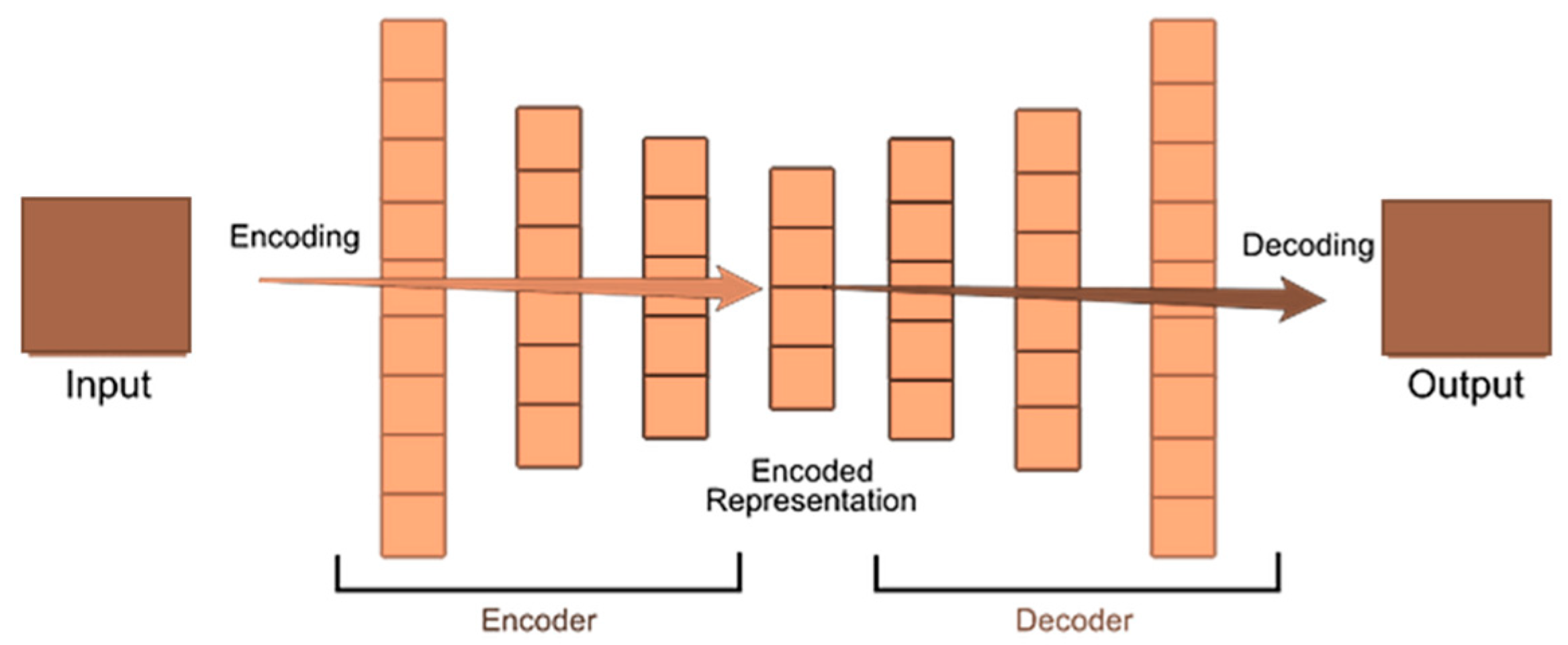

To achieve this, the proposed framework applies a deep autoencoder (deep-AE) to map the 80-dimensional input to a compact 21-dimensional latent space. As shown in

Figure 4, the first encoder layer performs the core compression step to create a lightweight representation, and subsequent layers extract higher-level behavioral structure that supports anomaly scoring. This multi-stage design provides a balance between computational efficiency and representational quality.

The autoencoder consists of an 80-neuron input layer connected to a 21-neuron latent layer, followed by a symmetric decoder that reconstructs the original feature vector. Training minimizes mean squared error (MSE), encouraging the latent space to preserve the statistical properties of normal traffic. ReLU activation in the encoder supports nonlinear compression, while sigmoid activation in the decoder reconstructs the input. Z-score normalization and Adam optimization promote stable convergence during training.

After training, only the encoder is deployed. Each incoming flow is projected into its 21-dimensional latent vector, reducing memory usage and inference time on fog nodes. These latent vectors serve two downstream roles: the deeper AE module computes reconstruction-error scores for anomaly identification, and DBSCAN operates only on high-error latent vectors during clustering. This avoids applying clustering to the full dataset and removes dependence on packet-payload inspection, which is often impractical due to encryption.

Overall, the dimensionality-reduction stage reduces computational overhead, filters noise, and improves scalability, enabling real-time intrusion detection within resource-constrained fog-computing environments.

3.4. Proposed Deep Autoencoder Architecture for Anomaly Detection

The core of the proposed framework is a deep autoencoder (deep-AE), as shown in

Figure 4, which is a symmetric neural network architecture designed to learn compact, meaningful representations of high-dimensional input data in an unsupervised manner. In the context of this study, the deep-AE [

35,

36] is leveraged to extract latent features from IoT network flows and facilitate the separation of benign and anomalous traffic patterns through clustering.

3.4.1. Architecture Layers

The autoencoder is designed to learn compact and expressive representations of IoT network traffic for anomaly detection in fog-enabled smart farming systems. The architecture includes four components: input layer, encoder, bottleneck (latent space), and decoder. The input layer receives normalized flow-based vectors of 80 numerical features derived from the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset after preprocessing. Redundant and low-value attributes are removed to improve generalization and reduce computation. The encoder consists of a sequence of fully connected layers with gradually decreasing dimensionality. In this study, a deep autoencoder (deep-AE) with four hidden layers is used. Each encoder layer compresses the input further, capturing hierarchical abstractions and nonlinear relationships among flow-level attributes. The first encoder layer performs lightweight dimensionality reduction to generate a compact 21-dimensional representation. This step is computationally lightweight and allows efficient processing on fog nodes, where memory and latency constraints are critical. At the core of the network is the bottleneck layer, which forms the latent feature space. This representation retains the most discriminative structural and statistical properties of the input while discarding noise and redundancy. The latent vector produced in this layer is later used for anomaly scoring and clustering. The decoder mirrors the encoder structure. Its dense layers gradually expand the latent vector back to the original 80-dimensional space. The reconstruction error—the difference between the input and the decoded output—is computed for each flow. Higher errors indicate deviation from learned patterns of benign behavior and therefore signal potential anomalies.

Figure 5 summarizes the end-to-end anomaly detection pipeline, covering preprocessing, encoding, latent-space compression, reconstruction, and anomaly scoring. This hierarchical design enables computational efficiency and strong discriminative capability, supporting real-time intrusion detection on fog-assisted smart farming IoT infrastructures.

3.4.2. Activation Functions and Loss Function

To ensure nonlinearity and enhance representational capacity, the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function (2) is applied in all encoder and decoder layers, except for the final output layer. ReLU is computationally efficient and helps address the vanishing gradient problem during training, which is especially important for deep networks. Formally, for an input latent feature vector R

D, ReLU is defined as:

For the output layer, a Sigmoid activation function (3) is used to produce continuous-valued reconstructions of input features. This design choice enables the model to capture subtle variations in network traffic behavior, which is critical for accurate anomaly detection.

The loss function used for training the autoencoder is Mean Squared Error (MSE), which measures the reconstruction error (4) between the original input and its reconstruction. Minimizing this error helps the model learn compact representations that preserve the most informative aspects of the data. Flows with significantly high reconstruction errors are considered anomalous, as the autoencoder has not learned to accurately reproduce them—indicating deviation from normal behavior. The reconstruction RC

D is computed as:

where

RCD denotes the reconstructed feature vector,

W′ is the decoder weight matrix, R

D is the latent representation,

b′ is the decoder bias, and

g(

⋅) is the activation function (Sigmoid).

3.4.3. Training Optimization

The deep autoencoder is trained using the Adam optimizer, which combines the advantages of the Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (AdaGrad) and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp). Adam enables efficient gradient-based optimization by dynamically adjusting the learning rate for each parameter, making it particularly effective for high-dimensional data such as IoT traffic flows. Early stopping is employed with a defined patience value to prevent overfitting and reduce unnecessary training epochs. This adaptive learning mechanism not only accelerates convergence but also enhances training stability, especially in deep and basic autoencoder architectures.

3.4.4. Threshold-Based Anomaly Identification

To differentiate between benign and anomalous traffic, a threshold is applied to the reconstruction error generated by the autoencoder. Instead of relying on fixed statistical percentiles, this study adopts a standard deviation-based thresholding approach, which is both robust and data-driven.

The threshold is computed using the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of reconstruction errors obtained from the training set. A data point is flagged as anomalous if its reconstruction error exceeds a threshold (T) defined in (5):

where k is a configurable hyperparameter that controls the sensitivity of the detection.

This approach ensures that only data points exhibiting significantly higher reconstruction errors than the typical range are considered anomalous. By filtering based on this threshold, the framework minimizes false positives and focuses clustering efforts (e.g., using DBSCAN) on genuinely suspicious traffic patterns, thus improving the accuracy and interpretability of cyber threat detection.

Overall, this deep-AE architecture is central to the unsupervised anomaly detection pipeline, enabling the transformation of high-dimensional flow-based IoT traffic into a compact latent space suitable for clustering and threat categorization at the fog level.

3.5. Latent-Space Clustering Using DBSCAN

After extracting compact and meaningful latent representations (R

D) from flow-based IoT traffic using an AE, and detecting the anomaly from deep-AE, the next crucial step involves clustering these detected anomalous from the encoded data points to identify and categorize anomalous behaviors. In this study, the Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) [

37,

38] algorithm is adopted as the primary clustering technique due to its suitability for detecting arbitrarily shaped clusters and handling noise and requires no pre-defined number of clusters in unsupervised settings. DBSCAN is a non-parametric clustering algorithm particularly well-suited for detecting outliers and grouping anomalies in unlabeled data. Unlike K-Means, DBSCAN does not require the number of clusters to be specified in advance and is capable of identifying noise points that do not belong to any cluster—a valuable feature for real-world anomaly detection scenarios.

In this framework, DBSCAN is applied to the latent vectors generated by the first hidden layer of the deep autoencoder. These vectors represent reduced-dimensional embeddings of the original input and emphasize the underlying structure of the data. The focus is on those latent representations corresponding to data points flagged as anomalous, identified based on high reconstruction error—calculated as the difference between the input and the reconstructed output of the autoencoder. A higher reconstruction error indicates a greater deviation from normal learned patterns, serving as a reliable anomaly score. By filtering and clustering only those data points with reconstruction errors above a defined threshold, the framework enhances DBSCAN’s ability to isolate dense anomaly clusters and noise points. This targeted clustering approach improves the interpretability and categorization of malicious behavior in flow-based IoT traffic. The DBSCAN algorithm, detailed in Algorithm 1, uses two key parameters: ε (epsilon), which defines the neighborhood radius, and MinPts, the minimum number of points required to form a dense region. These parameters are initially chosen based on heuristics and later fine-tuned through empirical experimentation to optimize cluster quality and improve the separation of abnormal traffic patterns.

| Algorithm 1 Latent-Space Clustering with DBSCAN for Anomaly Categorization |

Input:

- RD: Original flow-based IoT traffic data

- AE: Trained deep autoencoder model

- ε: Neighborhood radius parameter for DBSCAN

- MinPts: Minimum points to form a cluster in DBSCAN

- Threshold: Reconstruction error cutoff to select anomalies

Output:

- Cluster labels for anomalous data points (including noise)

Steps:

1. Encode data to latent space

RD = AE.encode(D)

2.Compute reconstruction errors for each data point

Recon_RD = AE.decode(RD)

Errors = compute_reconstruction_error(RD, Recon_RD)

3. Filter latent vectors corresponding to anomalies

AnomalyIndices = {i | Errors[i] > Threshold}

RDP_anomalous = RD[AnomalyIndices]

4. Apply DBSCAN clustering on filtered latent vectors

ClusterLabels = DBSCAN(RDP, ε, MinPts)

5. Assign noise label (−1) to non-anomalous data points

For i in {0 … length(RDP) − 1} do

If i not in AnomalyIndices then

ClusterLabels_full[i] = −1

Else

ClusterLabels_full[i] = ClusterLabels[corresponding index]

End If

End For

6. Return ClusterLabels_full |

Unlike traditional IDS deployments that operate in the cloud, smart farming relies heavily on fog-layer gateways positioned near agricultural devices. These nodes are resource constrained and operate on streaming flow-level telemetry rather than payload inspection due to privacy and bandwidth limitations. The proposed hierarchical AE + latent-gated DBSCAN pipeline was therefore selected because (i) shallow AE reduces dimensionality to meet fog compute limits, (ii) reconstruction-error scoring avoids labeled datasets typically unavailable in agricultural deployments, and (iii) DBSCAN can categorize heterogeneous cyber-attacks even when their number is unknown in advance—a behavior observed in precision agriculture networks subjected to botnet, scanning, and DoS activities.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

After extracting dense and semantically informative latent representations (referenced as RD) from flow-based IoT traffic through the autoencoder (AE), and subsequent detection of anomalous points through the deep autoencoder (deep-AE), the next crucial step is to cluster these anomalous points. This clustering is unavoidable in the process of discovering unique malicious patterns and enabling categorization of heterogeneous cyber threats. DBSCAN algorithm is used here as the main clustering approach. DBSCAN is especially favorable for the task in this scenario because it can identify clusters of any shape, is robust against noise and outliers, and does not require a priori knowledge about the number of clusters—thus being particularly adequate for unsupervised anomaly detection applications in dynamic IoT systems. Since it is a non-parametric clustering algorithm, DBSCAN clusters data points based on the local neighborhood density. In contrast to centroid-based algorithms like K-Means, DBSCAN automatically detects noise points that do not fit into any dense region, which is particularly useful in real-world intrusion detection, where unusual behavior tends to vary substantially from typical traffic distributions.

In the proposed framework, DBSCAN is applied specifically to the latent vectors obtained from the first hidden layer of the deep-AE, which provides an intermediate-level feature embedding that captures the structural essence of the input data. These vectors correspond to those input samples that exhibit high reconstruction error—a metric computed as the discrepancy between the original input and its reconstructed output from the autoencoder. A large reconstruction error indicates large deviation from the normal traffic learned distribution, hence making it a strong anomaly score. To further improve the accuracy and interpretability of clustering, only those latent vectors corresponding to reconstruction errors above a specified threshold are transmitted to DBSCAN. This filtered clustering reduces attention to significant anomalies, allowing DBSCAN to better differentiate dense clusters of bad behavior and extract noise points that could correspond to new or low-frequency attack categories.

DBSCAN is based on two hyperparameters with vital importance:

- ▪

ε (epsilon): determines the size of the neighborhood surrounding each point.

- ▪

MinPts: determines the minimum number of neighboring points needed to create a dense cluster.

These values are first established via domain-driven heuristics and then further optimized via empirical testing to ensure optimization of clustering quality and improved separation of varied types of anomalies in flow-based IoT traffic. This combination of DBSCAN clustering with autoencoder-based latent representation learning allows context-aware categorization of threats, providing better granularity in distinguishing among various classes of attacks and still being robust to noise and the dynamic nature of cyber threats in smart farming situations.

4.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments in this research were conducted using Google Colab, a cloud-based platform that facilitates access to powerful computational resources. The implementation was carried out in Python 3.10, utilizing libraries such as NumPy 1.26, Pandas 2.1, Matplotlib 3.8, Scikit-learn 1.4, and TensorFlow 2.15/Keras 2.15 for data preprocessing, model development, and visualization. To accelerate the training process, a NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU was employed through Colab’s hosted runtime environment. The combination of a high-performance GPU and a robust Python-based ecosystem enabled efficient handling of deep learning workflows and large-scale datasets.

Table 1 presents the dataset configuration and class distribution employed in this study, highlighting the composition of training and validation data along with the feature dimensions and instance counts.

Table 2 outlines the hyperparameter settings used during the training process, detailing the configuration choices that guided the optimization and model development.

4.2. Performance Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Deep-AE model, four widely used classification metrics were employed: precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. These metrics, derived from the confusion matrix, provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s classification performance. Precision (6) measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances among all instances predicted as positive. Recall (7), also known as sensitivity, indicates the proportion of correctly identified positive instances among all actual positives. The F1-score (8) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced measure that accounts for both false positives and false negatives. Accuracy (9) reflects the overall correctness of the model by measuring the proportion of all correctly classified instances. For the evaluation of the unsupervised DBSCAN model, two clustering-specific metrics—Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI) and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)—were used in addition to the standard evaluation metrics: precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. The DBI assesses the quality of clustering by evaluating intra-cluster compactness and inter-cluster separation—lower DBI values indicate more distinct and compact clusters, which is desirable. The ARI measures the similarity between the clustering results and ground truth labels, adjusted for chance. ARI values range from −1 (poor agreement) to 1 (perfect clustering), with higher values reflecting better clustering performance.

4.3. Convergence Behavior of the Autoencoder’s First Hidden Layer

The loss curve presented in

Figure 6 illustrates the training and validation loss over 49 epochs for the Autoencoder’s first hidden layer, trained on the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset. Both losses decrease sharply during the initial epochs, indicating that the model quickly captures the underlying patterns in the data. Around epoch 10, the rate of decrease begins to slow, and by epoch 20, both training and validation losses stabilize at low values, suggesting that the model has effectively converged. The close alignment between the training and validation losses throughout the training process reflects strong generalization capability with no signs of overfitting. By epoch 49, the loss values remain minimal and stable, confirming that the Autoencoder has accurately learned to reconstruct normal input data. This stable convergence at the final epoch validates the effectiveness of the first hidden layer as a foundational component for the subsequent stages of the anomaly detection pipeline.

4.4. Attack Detection Performance of the Deep Autoencoder Model

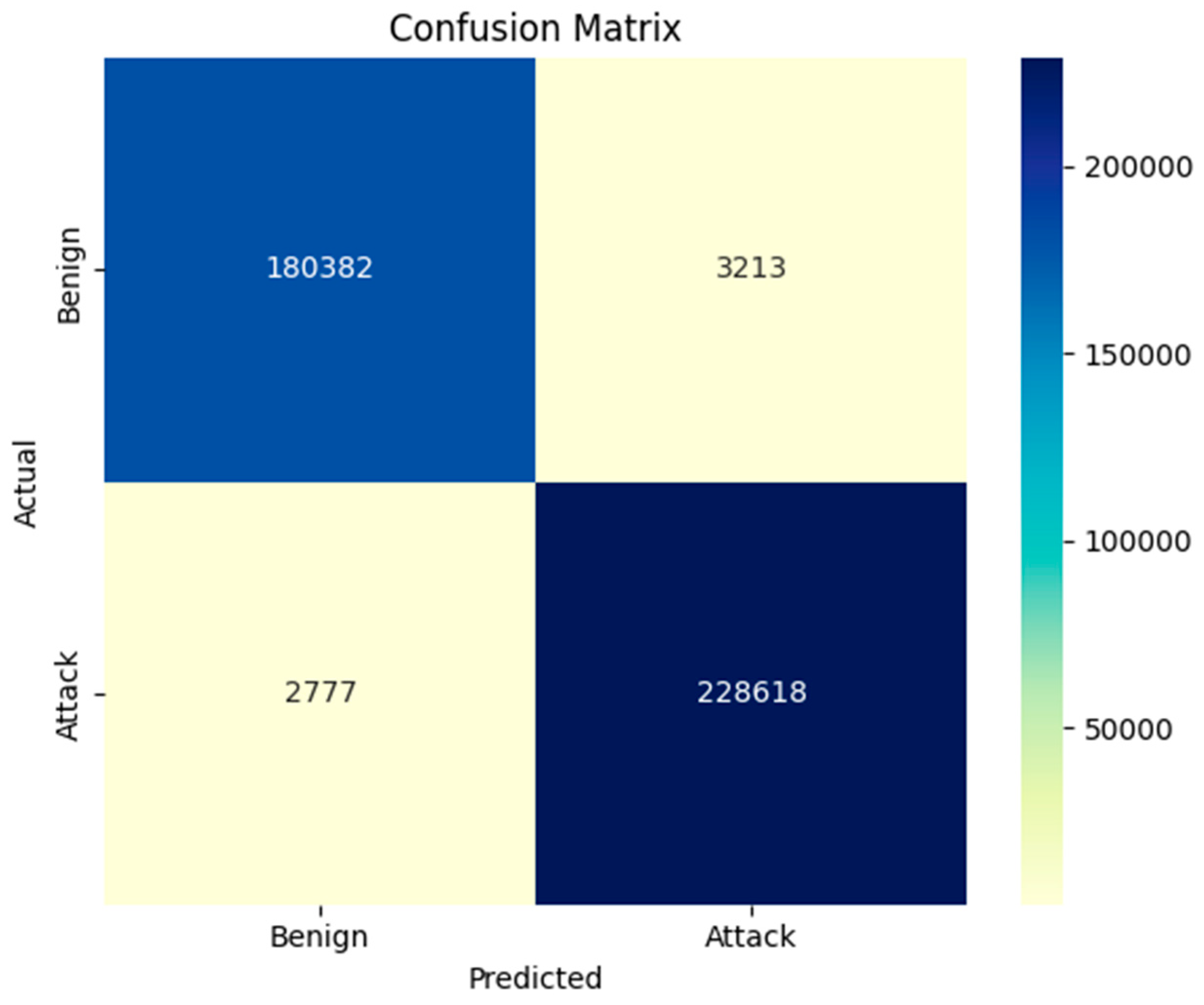

The attack detection capability of the deep autoencoder (deep-AE) was first evaluated on the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset using a confusion matrix, as shown in

Figure 7. The model correctly identified 180,382 benign flows and 228,618 malicious flows, while misclassifying 3213 benign flows as attacks (false positives) and 2777 attacks as benign (false negatives). Based on these outcomes, the model achieved an overall accuracy of 98.56%, with 98.61% precision, 98.80% recall, and an F1-score of 98.71%. These metrics confirm that the deep-AE effectively separates normal and abnormal traffic patterns and is well suited for real-time intrusion detection in smart farming networks.

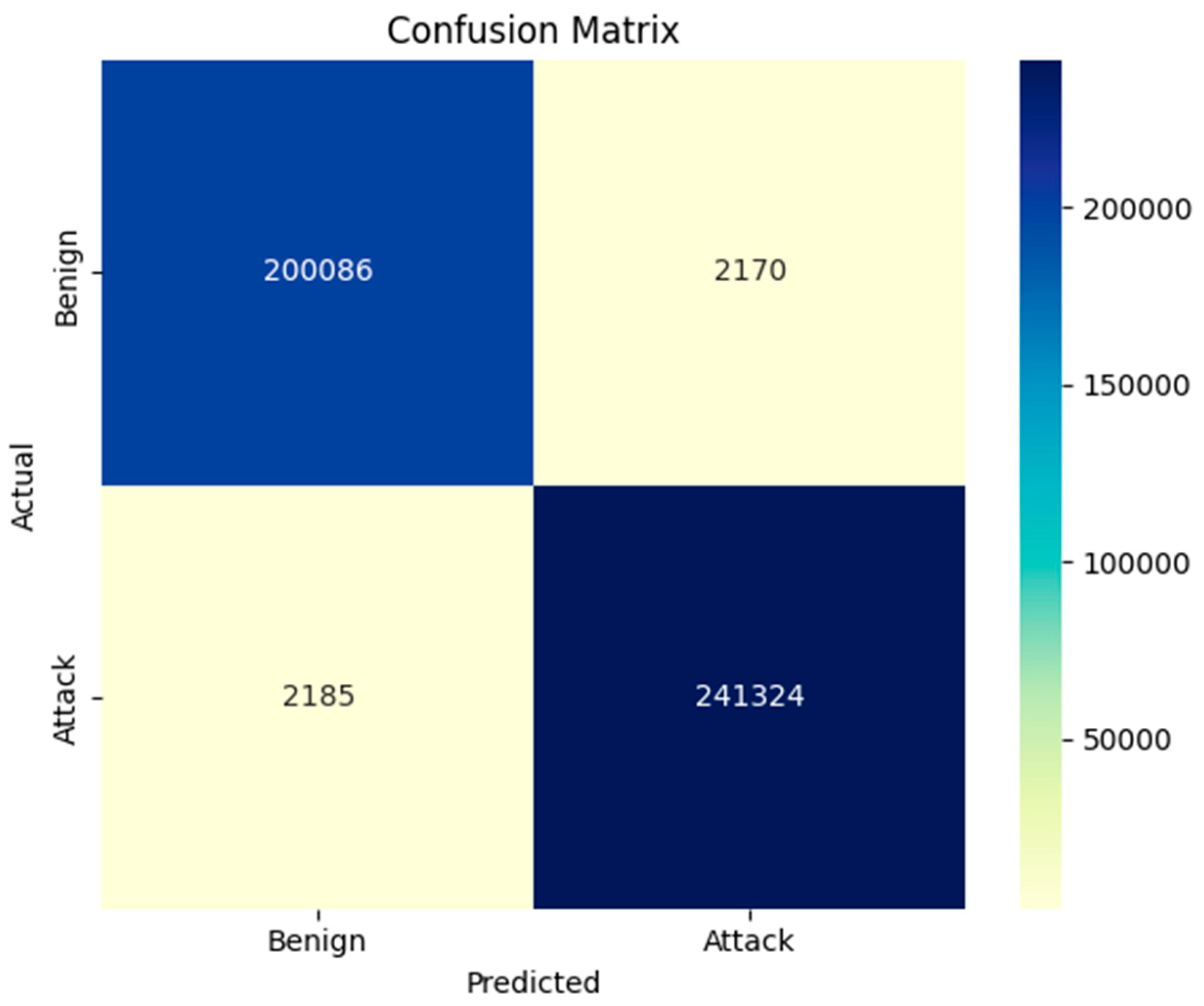

To assess generalizability beyond smart farming IoT traffic, the model was additionally evaluated on the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 benchmark. The confusion matrix for this dataset is shown in

Figure 8. The model correctly classified 241,324 attack instances (TP) and 200,086 benign instances (TN), while 2170 benign instances were incorrectly flagged as attacks (FP) and 2185 attacks were missed (FN). These results correspond to an overall accuracy of 99.02%, with 99.11% precision, 99.10% recall, and an F1-score of 99.11%.

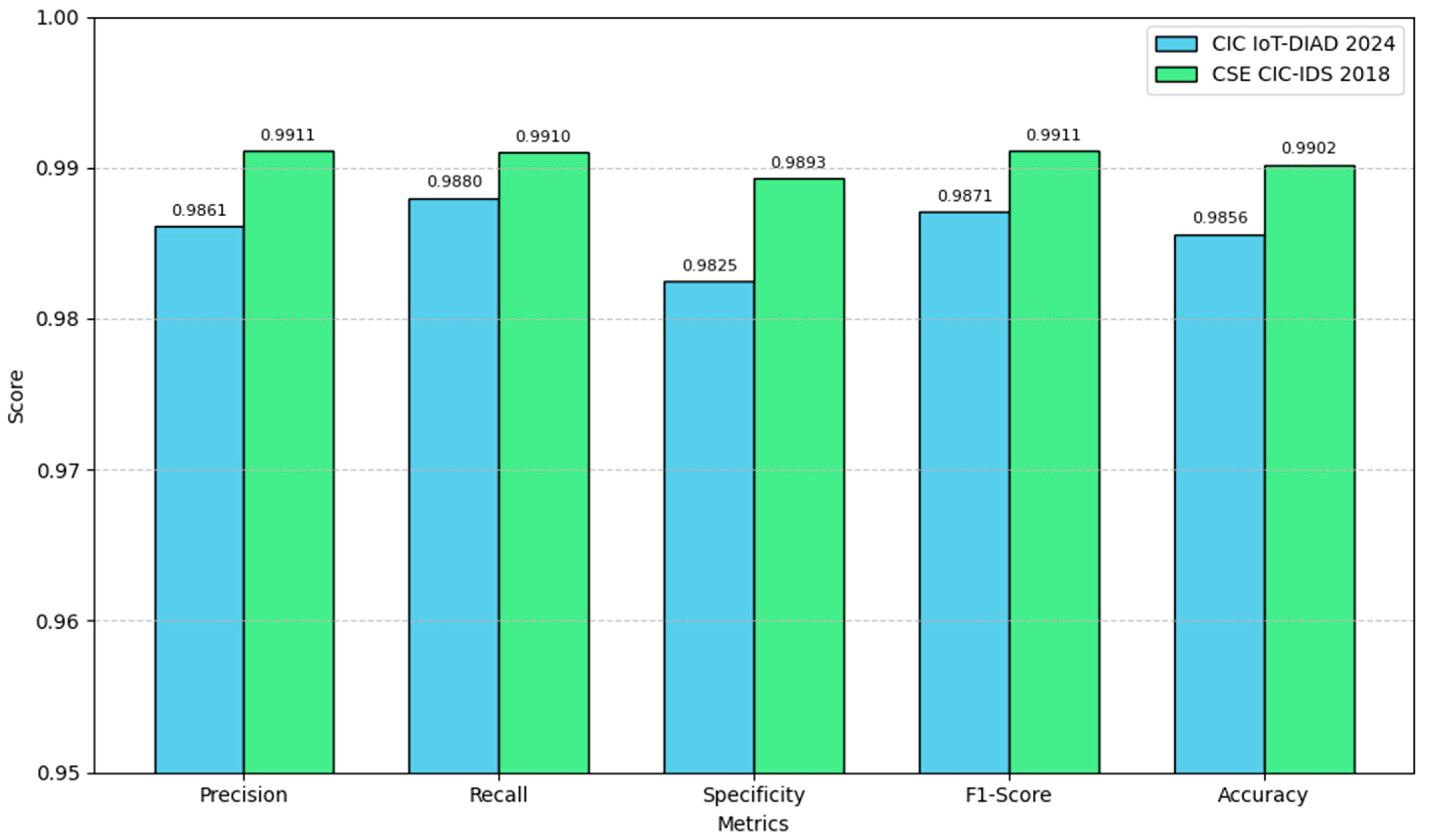

A combined comparison of performance metrics across both datasets is illustrated in

Figure 9, highlighting that the model consistently maintains high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across heterogeneous IoT traffic conditions. The low false-positive and false-negative rates across both datasets demonstrate robustness and adaptability to distinct threat landscapes. Overall, these findings confirm that the proposed deep-AE architecture reliably detects cyberattacks across different traffic domains—not only smart farming networks but also broader enterprise-scale IoT infrastructures—while remaining suitable for deployment on resource-constrained fog computing platforms.

4.5. Comparative Evaluation of the Proposed Deep Autoencoder with State-of-the-Art Models

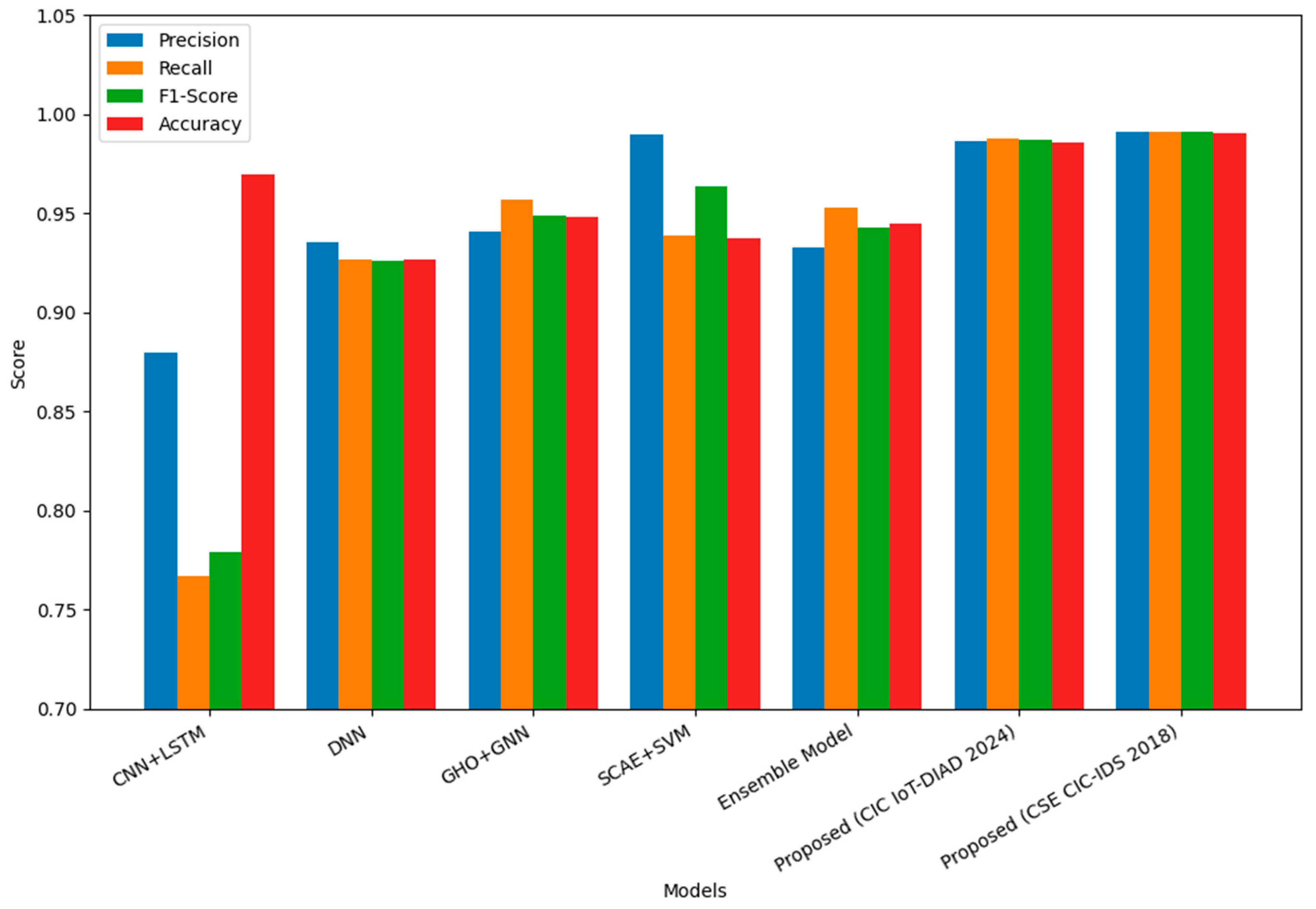

The performance of the proposed deep autoencoder (deep-AE) model was benchmarked against five leading intrusion detection approaches—CNN + LSTM, Deep Neural Network (DNN), Graph Neural Network with Grey Wolf Optimizer (GHO + GNN), Stacked Convolutional Autoencoder with SVM (SCAE + SVM), and an Ensemble Model—using the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset. As presented in

Table 3, the proposed model achieved the highest overall performance across all four evaluation metrics, with 0.9861 precision, 0.9880 recall, 0.9871 F1-score, and 0.9856 accuracy. While SCAE + SVM displayed a slightly higher precision (0.9897), its considerably lower recall (0.9390) reduced its F1-score (0.9637), indicating a higher rate of missed attacks. Likewise, the GHO + GNN model obtained a reasonable F1-score (0.9490) but underperformed relative to the proposed model in both precision and accuracy. The CNN + LSTM method recorded the lowest recall (0.7668), suggesting limited capability in detecting the full spectrum of attacks. The Ensemble Model achieved strong recall (0.9530) but exhibited lower precision (0.9330), leading to more false alarms.

The CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset was additionally used to assess generalizability beyond smart farming IoT traffic. On this dataset, the proposed deep-AE continued to maintain high performance, achieving 0.9911 precision, 0.9910 recall, 0.9911 F1-score, and 0.9902 accuracy, demonstrating that the model retains a balanced detection capability even under enterprise-scale threat scenarios with markedly different traffic distributions.

Overall, the comparative results confirm that the proposed framework consistently sustains an optimal balance between precision and recall across both datasets—minimizing false positives as well as undetected threats. This balance is especially important for real-time intrusion detection in resource-constrained fog computing environments, where both reliability and efficiency are critical. The performance trends summarized in

Figure 10 show that the proposed deep-AE maintains consistently strong detection results across multiple metrics. The figure also illustrates that, compared with representative state-of-the-art approaches, the model achieves a more balanced precision–recall profile, which supports its suitability for dependable fog-based intrusion detection.

4.6. Clustering Performance Analysis of the Proposed Deep-AE + DBSCAN Model

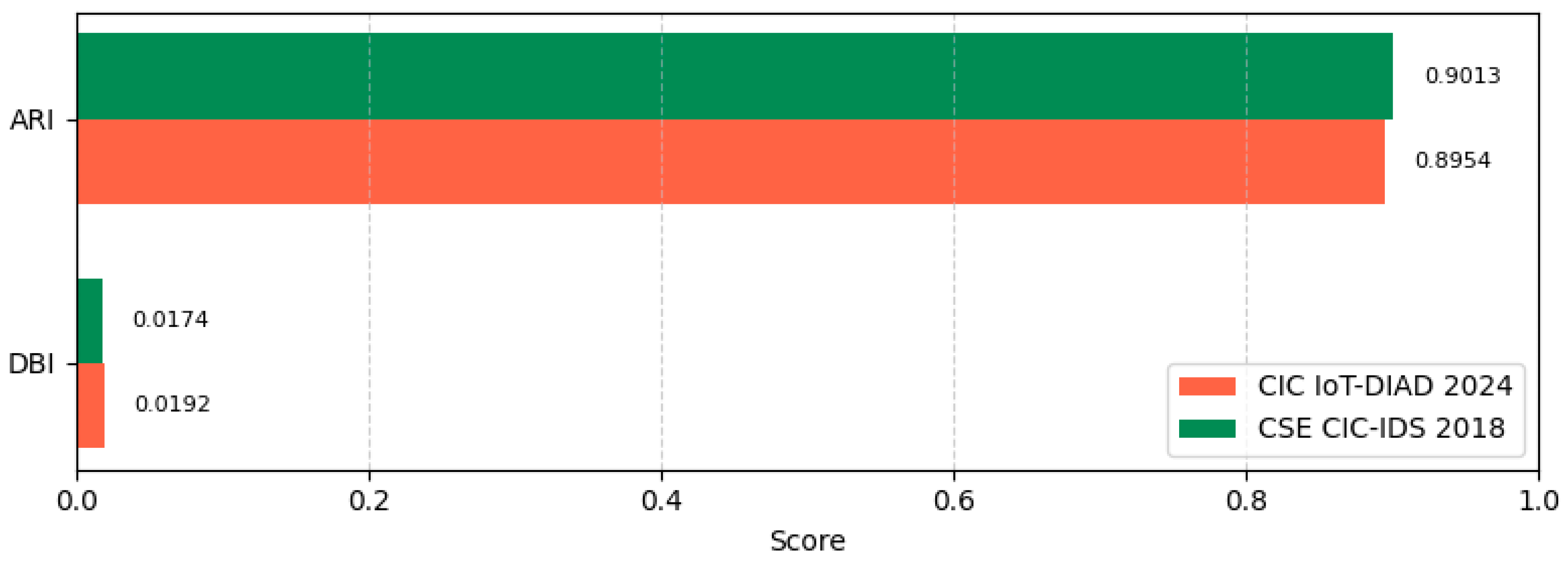

As shown in

Figure 11, the proposed deep-AE + DBSCAN framework demonstrates strong clustering performance across both benchmark datasets. On the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset, DBSCAN achieves an Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) of 0.895 and a Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI) of 0.019, indicating that the clusters are highly consistent with the ground-truth categories and exhibit excellent compactness and separation. To further evaluate clustering robustness beyond smart farming traffic, the model was also assessed on the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset, where it attained an ARI of 0.9013 and a DBI of 0.0174. These values reflect even stronger cluster separability and cohesion under enterprise-scale IoT traffic.

Across both datasets, the consistently high ARI and low DBI scores confirm that the proposed method effectively captures attack-specific behavioral patterns while minimizing noise influence—an essential property for reliable unsupervised intrusion detection in heterogeneous and resource-constrained IoT environments.

4.7. Comparative Evaluation of Proposed Deep-AE + DBSCAN Against Existing Clustering-Based Intrusion Detection Methods

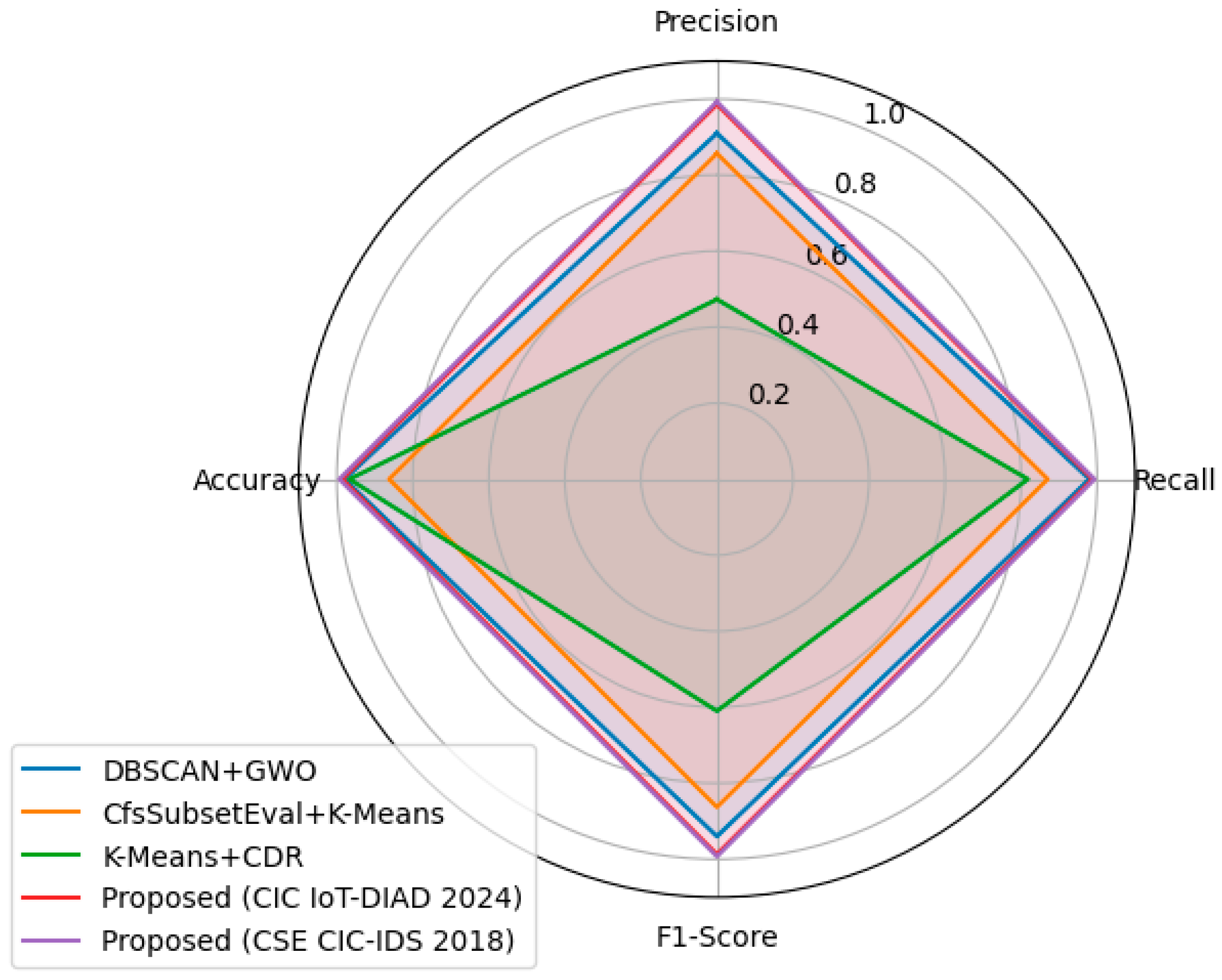

The performance of the proposed Deep-AE + DBSCAN model was benchmarked against three widely used clustering-based intrusion detection approaches—DBSCAN + GWO, CfsSubsetEval + K-Means, and K-Means + CDR. As shown in

Table 4, the proposed model delivers the highest performance across all evaluation metrics on both datasets. On the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset, it achieves 0.9872 precision, 0.9902 recall, 0.9897 F1-score, and 0.9899 accuracy. On the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset, it further improves to 0.9929 precision, 0.9932 recall, 0.9928 F1-score, and 0.9933 accuracy. Compared to the next best model, DBSCAN + GWO—whose F1-score (0.94) and accuracy (0.98) are competitive—the proposed framework exhibits clear advantages in precision and recall. This improvement indicates a more balanced detection capability, minimizing both false positives and false negatives. CfsSubsetEval + K-Means and K-Means + CDR show noticeably lower overall performance, with F1-scores of 0.863 and 0.610, respectively. In particular, K-Means + CDR demonstrates high recall (0.818) but poor precision (0.473), suggesting a high false-alarm rate and limited suitability for operational deployment.

Overall, the results—summarized in

Table 4 and visualized in

Figure 12—indicate that the proposed Deep-AE + DBSCAN approach provides a consistently strong performance compared with existing clustering-based IDS methods. The balanced precision, recall, and accuracy observed across two heterogeneous benchmarks demonstrate robust detection capability and low false-alarm rates. These findings suggest that the framework is well suited for reliable intrusion detection in diverse IoT environments, including resource-constrained smart farming infrastructures.

4.8. Ablation Study

To quantify the contribution of each major component in the proposed framework—shallow autoencoder (AE), deep AE, latent-space gating, and DBSCAN—an ablation study was conducted on the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset. Five model variants were evaluated in a cumulative manner:

As summarized in

Table 5, the Shallow AE only and Deep AE only variants achieve modest performance, confirming that neither dimensionality reduction nor reconstruction-based anomaly scoring alone is sufficient for reliable intrusion detection. Introducing DBSCAN to the Shallow AE improves clustering-based categorization but results in lower precision due to benign flows entering the clustering space.

A notable performance jump occurs when the Shallow AE and Deep AE are combined, indicating that lightweight dimensionality reduction strengthens the latent representation and improves anomaly scoring. The best results are obtained with the full proposed pipeline, in which latent-space gating filters high-error latent vectors prior to clustering, preventing noise contamination, improving cluster separability, and significantly reducing false positives and missed detections.

Overall, the ablation study confirms that each module contributes meaningfully:

the Shallow AE improves low-dimensional feature representation,

the Deep AE strengthens anomaly discrimination,

DBSCAN enables label-free attack categorization, and

latent-space gating ensures noise-resilient clustering.

Only the full synergy of all four components yields optimal performance.

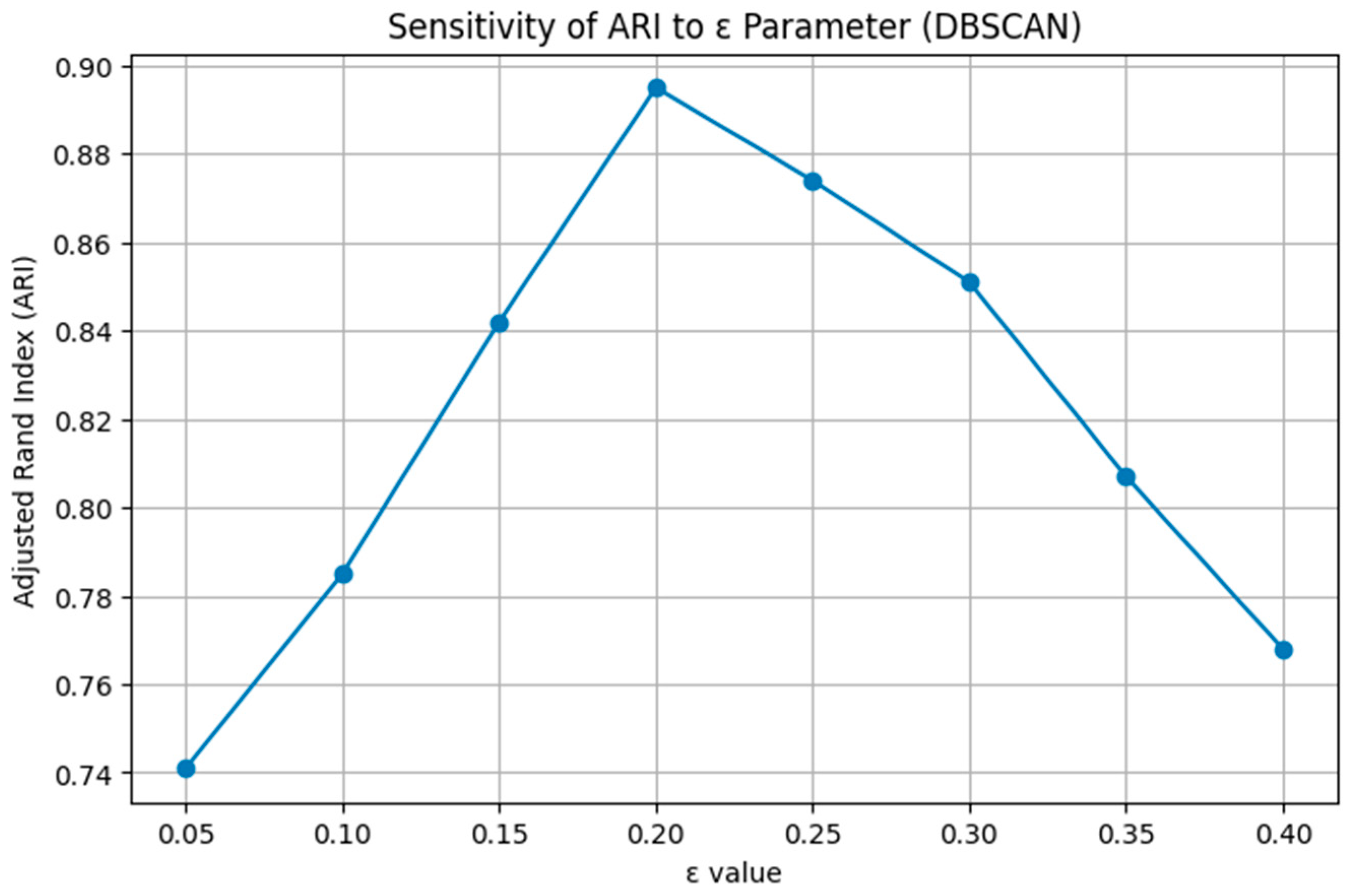

4.9. DBSCAN Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To justify the selected DBSCAN configuration, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset by varying ε and MinPts while keeping all other components of the framework unchanged. The results, shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, indicate that clustering performance is highly dependent on both parameters. The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) increases steadily with ε and reaches its maximum at ε = 0.20, after which performance declines due to cluster merging. A similar pattern is observed for MinPts: values below 3000 produce many small, fragmented clusters, whereas larger values merge distinct attack behaviors and reduce separability. The best clustering performance is achieved at MinPts = 3000, yielding an ARI of 0.895 and the lowest DBI value. These results confirm that ε = 0.20 and MinPts = 3000 provide the optimal balance between compact intra-cluster structure and clear inter-cluster separation. Thus, the chosen DBSCAN parameters represent the empirically optimal configuration for maximizing clustering quality and anomaly categorization performance.

4.10. Fog-Node Computational Efficiency Analysis

Although model training was performed using GPU resources on Google Colab, the proposed framework is intended for deployment at the fog layer of smart farming IoT infrastructures. To evaluate real deployment feasibility, the trained model was exported and executed on two representative fog-class devices—Raspberry Pi 4 (4 GB RAM) and NVIDIA Jetson Nano (4 GB RAM)—in addition to the reference execution on Google Colab (Tesla T4 GPU). All experiments measured end-to-end inference performance, including preprocessing, shallow AE encoding, deep AE reconstruction-error scoring, latent-space gating, and DBSCAN-based clustering.

As summarized in

Table 6, the full inference pipeline maintains real-time operation even under resource-constrained conditions. The Raspberry Pi 4 achieved 6.42 ms per flow (155 flows/s) with a peak memory use of 482 MB and an average CPU utilization of 71%. The Jetson Nano delivered a higher throughput of 321 flows/s with 3.11 ms per flow, while maintaining 461 MB of memory and balanced utilization of 58% GPU and 39% CPU. For reference, the T4 GPU processed 0.74 ms per flow (1351 flows/s) with low utilization overhead, demonstrating scalability when deployed on higher-end hardware.

Importantly, latent-space gating reduced the number of flow vectors sent to DBSCAN by approximately 37%, lowering clustering cost and helping sustain real-time throughput even during high-traffic bursts. The compact model size (≈9.3 MB) further enables deployment without external accelerators or cloud dependence.

Together, these results confirm that the framework is not only conceptually fog-aware in design but also practically deployable on low-power fog devices while meeting latency and memory constraints typical of smart farming networks.

4.11. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Intrusion Detection Methods

Table 7 presents a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art intrusion detection techniques versus the proposed fog-aware hierarchical deep autoencoder (AE) with latent-space gated DBSCAN. Existing approaches—including hybrid ML–DL pipelines, graph neural networks, clustering–optimization hybrids, and federated learning frameworks—achieve accuracy values between 85.91% and 98.00% across various benchmark datasets. In contrast, the proposed model achieves 98.99% accuracy on the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset and 99.33% accuracy on the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset, placing it among the best-performing approaches in the comparison.

The strong performance of the proposed model is achieved without compromising computational efficiency, which is crucial for fog-level deployment in smart agriculture. While several high-performing prior methods depend on large labeled datasets, exhibit sensitivity to noise and parameter tuning, or generalize poorly across domains, the proposed two-stage framework—combining lightweight dimensionality reduction, deep feature reconstruction, and selective density-based clustering—circumvents these limitations. It effectively separates benign and malicious traffic even under noisy and dynamic network conditions, without requiring the number of attack categories in advance. Furthermore, the inclusion of clustering quality metrics—ARI = 0.895 and DBI = 0.019 on CIC IoT-DIAD 2024, and ARI = 0.9013 and DBI = 0.0174 on CSE-CIC-IDS2018—demonstrates the model’s ability to form compact, well-separated anomaly clusters, a performance dimension rarely assessed in prior literature.

Overall, this comparative evaluation confirms that the proposed model not only achieves the highest intrusion detection accuracy, but also offers improved adaptability, robustness, and real-time suitability for resource-constrained IoT and fog computing environments.

4.12. Discussion

The experimental results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage fog-aware deep autoencoder (Deep-AE) and its integration with latent-space gated DBSCAN for unsupervised cyber-threat detection. On the CIC IoT-DIAD 2024 dataset, the Deep-AE alone achieved an F1-score of 98.71%, precision of 98.61%, recall of 98.80%, and accuracy of 98.56%, confirming its capability to accurately differentiate benign and malicious traffic. The low false-positive and false-negative rates highlight strong detection sensitivity and specificity—key requirements for cybersecurity in resource-constrained smart farming environments.

The deep-AE also demonstrated competitive and often superior performance compared with representative intrusion detection models, including CNN-LSTM, DNN, GHO + GNN, SCAE + SVM, and ensemble-based approaches. Although SCAE + SVM achieved slightly higher precision, its substantially lower recall indicates missed attacks, whereas the proposed deep-AE preserves a balanced precision–recall profile, minimizing both false alarms and undetected threats. This balanced response is critical for operational reliability in fog-based deployments.

In the context of smart-farming operations, the impact of false alarms extends beyond cybersecurity metrics and directly influences agricultural automation and productivity. A high false-positive rate can trigger unnecessary blocking of benign sensor-to-gateway communication, potentially interrupting real-time irrigation scheduling, greenhouse climate control, or livestock monitoring—leading to operational delays and resource inefficiencies. Conversely, false negatives pose even greater risk, as undetected attacks may allow adversaries to manipulate sensor readings, disrupt actuator commands, or take control of autonomous devices without raising alerts. Therefore, maintaining a balanced precision–recall profile is essential for ensuring both reliability and safety in field deployments. The proposed hierarchical AE model meets this requirement by minimizing both types of errors: the deep autoencoder reduces missed detections through precise anomaly scoring, while the latent-space gating and DBSCAN clustering suppress false alarms by preventing benign but irregular flows from entering the clustering space. As a result, the framework supports dependable threat detection without compromising the continuity of automated agricultural processes.

When extended to the fully unsupervised scenario, coupling the Deep-AE with DBSCAN further enhanced classification performance through targeted clustering of high-reconstruction-error latent vectors. The deep-AE + DBSCAN combination yielded ARI = 0.895 and DBI = 0.019 on CIC IoT-DIAD 2024, and ARI = 0.9013 and DBI = 0.0174 on CSE-CIC-IDS 2018, confirming compact and well-separated clusters aligned with true attack patterns. Comparisons with DBSCAN + GWO, CfsSubsetEval + K-Means, and K-Means + CDR show that the proposed method achieved a more favorable balance of precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy, while maintaining a low false-alarm rate.

Importantly, fog-node benchmarking verifies that the full inference pipeline maintains real-time performance and modest memory usage even on low-power hardware. This confirms that the proposed system is not only theoretically fog-aware but also practically deployable in operational smart farming scenarios.

Overall, the results validate that the proposed hierarchical representation learning and selective clustering strategy delivers strong detection accuracy, efficient computation, and tangible applicability for securing distributed IoT networks in modern precision agriculture.

4.13. Limitations and Future Work

While the proposed framework exhibits strong detection and clustering performance across both IoT-specific and enterprise-scale datasets, several limitations remain that warrant further investigation. First, the reconstruction-error threshold used for anomaly identification is static, which may require recalibration in highly dynamic network environments; introducing adaptive or self-tuning thresholding mechanisms could enhance long-term deployment stability. Second, although DBSCAN proved effective for selective anomaly clustering, its scalability can become challenging for extremely large-scale or high-dimensional traffic. Future extensions may explore more scalable density-based algorithms—such as HDBSCAN or OPTICS—or adopt approximate clustering strategies to reduce computational overhead. Third, despite the architectural optimizations applied, deep autoencoder-based learning may still impose non-trivial computational demands on ultra-lightweight edge devices, suggesting the need for model-compression strategies, including pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation, to further improve deployability in constrained fog environments. Finally, although evaluation using the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset provided promising evidence of cross-domain generalizability, additional experiments using real-world multi-site agricultural deployments would offer deeper insights into performance under heterogeneous field conditions. Future work will focus on integrating adaptive thresholding, scalable clustering alternatives, and lightweight model implementations to further enhance robustness, efficiency, and real-time operational suitability across diverse IoT ecosystems.