1. Introduction

Pneumonia is a major global health issue, with over 450 million cases and approximately 4 million deaths annually, thus being an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially among vulnerable and elderly people [

1]. Patients with chronic neurological disorders may experience a severe course of the disease and an increased mortality risk when exposed to respiratory diseases [

2]. Pneumonia has been defined as an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma, mainly of alveolar sacs, and results in inflammation, collection of fluid and/or pus, and thereby impaired gas exchange [

3]. Clinically, these phenomena result in a collection of symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, dysphagia, chest pain, fever, and even hypoxia [

4]. However, in certain populations at risk, including patients with neurodegenerative diseases, these clinical symptoms may be altered, or even abolished, because of their impaired immunological response.

Pneumonia can be classified as community-acquired, hospital-acquired, or ventilator-associated, depending on the environmental setting in which it occurs. There are also several distinctions based on the microbial etiology and the time of onset. Numerous pathogens, such as

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Legionella pneumophila,

Haemophilus influenzae, atypical bacteria like

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, various influenza viruses, SARS-CoV-2, and fungi (like

Pneumocystis jirovecii) are examples of etiological agents [

5]. Clinical signs and symptoms, supported by imaging and laboratory results, are usually the basis for diagnostic confirmation.

Respiratory tract infections, particularly pneumonia, are considerably more common in patients with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and multiple sclerosis (MS). In addition to being a serious risk to life, pneumonia is a leading cause of hospitalization, extended recuperation, and higher mortality rates in these patients. It often leads to acute clinical deterioration and impacts long-term prognosis [

6].

Pneumonia episodes in these patients frequently result in increased frailty, loss of functional independence, and accelerated cognitive decline in addition to acute effects, making long-term care and disease management even more challenging. Rapid identification of early pneumonia symptoms is essential in this situation because it can avoid serious complications and lessen the burden of care

Pulse oximetry, arterial blood gas analysis, chest radiography (CXR), sputum analysis, blood cultures, urine antigen testing, and, if practical, bronchoscopy are among the diagnostic techniques that are available. CXR continues to be the key diagnostic tool for pneumonia, due to its accessibility and relatively high diagnostic accuracy. Automating its interpretation can support faster and more accurate clinical decisions.

In this regard, real-time, remote detection of pneumonia episodes is made possible by AI-driven tools that are integrated into IoT platforms. This is particularly applicable when those tools are incorporated into patient monitoring systems for individuals with neurodegenerative diseases.

AI-based solutions that can enable early, accurate, and continuous detection of pneumonia in neurodegenerative populations are needed, as these clinical vulnerabilities and diagnostic limitations in outpatient and long-term care settings underscore.

A new Machine Learning (ML) paradigm called Federated Learning (FL) [

7] allows several entities (devices, organizations, cars, etc.) to use their local data to train a common global model without exchanging it with a central server. In this way, medical institutions can keep their data local, preserving the patients’ privacy, mitigating security risks, and reducing the overhead caused by high-resolution medical images being transmitted and stored at the servers.

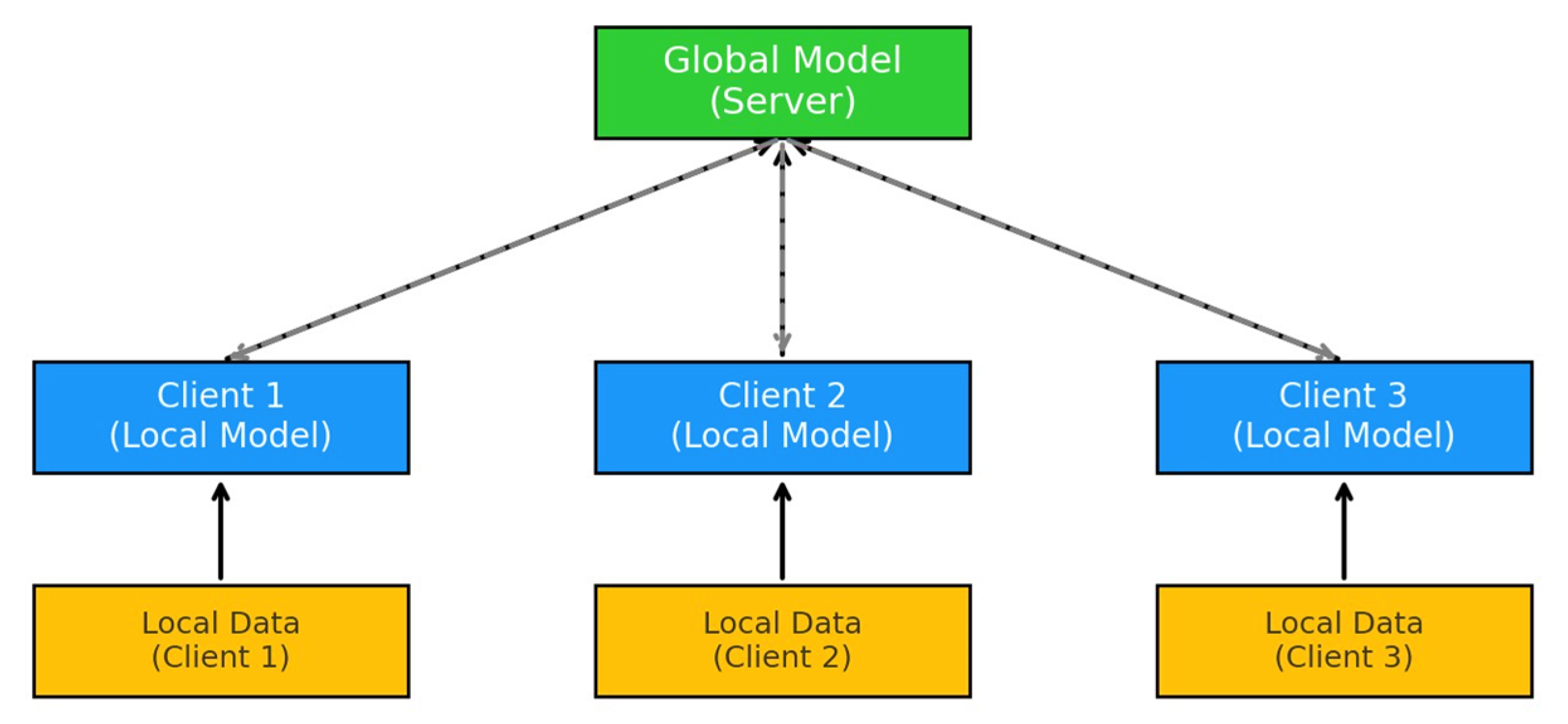

Figure 1 illustrates the basic architecture of FL. A global model is hosted on a central server, which coordinates the learning process. Each client (Client 1, Client 2, Client 3) trains its local model using its own local data, which remains on the client device to preserve privacy. After local training, the updated parameters (not the raw data) are sent back to the server, where they are aggregated to improve the global model.

This approach is gaining popularity in the medical imaging space, notably for CXR, where deep learning models require vast, heterogeneous datasets to generalize effectively [

8]. Deep Learning (DL) models have been proven particularly useful for detecting illnesses from medical images, such as Computed tomographies (CTs), Magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs), including CXR [

9], which remain a key diagnostic tool for pneumonia.

Building on prior work in FL for medical imaging, the authors created and evaluated a pneumonia detection model based on DL, which was specifically designed for distributed training on CXR data under varying simulated settings.

The rapid evolution of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies has enabled the development of distributed sensor systems for continuous physiological tracking [

10]. In healthcare, such platforms use wearable, ambient, and biomedical sensors to collect and transmit multimodal data for continuous assessment of patients’ health. This layered architecture, which includes sensing, local processing, communication, and cloud analytics, enables low-latency, privacy-aware decision support [

11,

12].

One representative example of such an IoT-based health platform is NeuroPredict, currently under development as part of a national R&D initiative in Romania [

13]. The platform is designed to support real-time, multimodal monitoring and adaptive care for patients with neurodegenerative conditions such as PD, AD, or MS. It integrates heterogeneous sensor data, behavioral indicators, cognitive scores, and physiological parameters using a layered architecture that accommodates modular AI components. The federated pneumonia detection approach proposed in this study aligns with this architectural framework and could be conceptualized as a diagnostic module for respiratory problems, which are a primary cause of deterioration and hospitalization in this population.

It is important to emphasize that the suggested model has not been clinically evaluated and is still in the proof-of-concept stage. It illustrates the technical viability of incorporating a federated AI component in IoT-based health solutions to diagnose pneumonia automatically. While not yet included in the NeuroPredict platform, the model is consistent with its modular architecture and fills a major monitoring need in neurodegenerative care via privacy-preserving respiratory surveillance.

Platforms such as NeuroPredict demonstrate how sensor-rich IoT ecosystems, integrating wearable devices, ambient monitoring units, and edge–cloud architectures, can support real-time, multimodal surveillance [

14] and personalized AI-driven decision support in chronic care settings. Moreover, the continuous monitoring, combined with the adaptive learning capabilities of FL, contributes to building a personalized, longitudinal medical history for each patient. This enhances both the contextual understanding of subtle clinical changes and the accuracy of predictive models over time, ultimately supporting earlier and more informed clinical decision-making.

Current computerized tools for monitoring neurodegenerative disorders, notably the NeuroPredict platform, focus primarily on monitoring cognitive, motor, and behavioral symptoms [

15,

16,

17]. However, they often lack integrated systems for recognizing acute, high-risk comorbidities such as pneumonia. By exploring diagnostic performance, robustness, and architectural feasibility, this study provides a proof of concept for embedding AI-based classification modules into smart sensor systems targeting comorbid conditions like pneumonia in vulnerable populations. The model is a technically feasible extension for improving real-time clinical surveillance in neurodegenerative care, even though it is not yet integrated into the NeuroPredict platform. It also aligns structurally and functionally with its modular architecture. By including an AI-driven method for detecting acute respiratory complications, the proposed pneumonia detection module would greatly increase the NeuroPredict platform’s functionality and improve its clinical relevance and responsiveness in handling complicated neurodegenerative cases.

Although several studies have explored the use of FL in radiological imaging, most focus on technical performance alone and do not address its deployment within real-world IoT-based health platforms [

18,

19,

20,

21]. These implementations mostly ignore the diagnostic requirements of neurodegenerative patients, who are especially susceptible to underdiagnosed pneumonia. This study intends to investigate whether incorporating a federated CXR classification model into a modular IoT architecture for ongoing respiratory surveillance in this patient population is feasible.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the clinical background on pneumonia in neurodegenerative patients, emphasizing the diagnostic challenges and unmet monitoring needs in PD and AD.

Section 3 describes the system architecture and implementation of the FL setup, including model configurations, training parameters, and data distribution schemes.

Section 4 reports the experimental results obtained in both centralized and federated scenarios, analyzing performance across optimizers, client configurations, and class imbalance conditions.

Section 5 discusses clinical implications, integration feasibility in IoT-based health platforms such as NeuroPredict, and the conceptual value of the proposed module in smart chronic care.

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions, discusses existing limitations, and proposes areas for future development and validation.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Pneumonia and Respiratory Vulnerabilities in Neurodegenerative Disorders

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, AD, and MS, are often accompanied by a progressive decline in motor coordination, bulbar function, cognitive capacity, and immune competence, creating a clinical environment that is suitable for recurrent infections. These patients are at a significantly higher risk of developing respiratory tract infections, especially pneumonia.

In AD and related dementias, impaired cognition and oropharyngeal coordination, leading to impaired swallowing (dysphagia), markedly increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia, often without overt symptoms, a situation that delays early diagnostic and treatment, increasing the risk of complications [

22]. In PD, rigidity of respiratory muscles, bradykinesia, and decreased cough strength, due to weakened respiratory muscles, lead to ineffective airway clearance, resulting in mucus retention and secondary bacterial infections [

23]. Similarly, the progressive weakening of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles in MS and MS impairs ventilatory efficiency, decreasing oxygen exchange and increasing the risk of opportunistic infections and atelectasis.

A large number of these patients are institutionalized for an extended period of time, frequently in long-term care facilities where multidrug-resistant pathogens are more common. This raises the risk of healthcare-associated pneumonia, which is linked to a more complicated treatment plan and a higher death rate. Due to their chronic immunosuppressive state, these populations can also have reduced or absent pneumonia-specific signs and symptoms, such as productive cough, leukocytosis, and febrile response, which could result in underdiagnosis or delayed detection.

The clinical consequences of pneumonia in patients with neurodegenerative disorders are greater than in other people suffering from pneumonia, because this pathological condition is associated, in their specific case, with increased mortality and morbidity, frequent hospital admissions and longer recovery times, and also accelerated decline in their neurological and functional status. That is why pneumonia is a leading cause of death in advanced-stage PD and AD.

In this context, there are some diagnostic challenges of pneumonia in neurodegenerative conditions: symptoms can be nonspecific or masked by baseline neurological deficits, underdiagnosis is common due to communication barriers and subtle onset, and, at the same time, there is frequently limited access to imaging in long-term care facilities or home settings.

In real-world clinical practice, there is a lack of structured monitoring for early respiratory decline, limited access to radiology for outpatients, and no tailored surveillance strategies in neurologic cases. Despite its accessibility, CXR interpretation requires trained radiologists, which may not be available in all settings.

That is why there is a real need for early detection through continuous monitoring systems. Automated, AI-driven tools are needed to support clinical decision-making in vulnerable neurodegenerative patients.

2.2. Federated Learning Approaches in Medical Imaging

Since FL was first introduced by McMahan in 2017 [

7], applications using it have emerged in various fields, such as IoT [

24], cybersecurity [

25] or the medical field [

26].

In the field of medical imaging, where centralized approaches are problematic because of large file sizes and strict privacy regulations, this is especially helpful. It improves resilience and scalability in diverse healthcare settings [

27].

According to [

28], ML algorithms can be used to identify pneumonia from radiological images, and for these applications it is well known that the existence of a database with labeled images, acquired and preprocessed correctly, is very important.

In real-world FL scenarios, a number of practical restrictions affect system performance and dependability. First, the data among clients is frequently non-IID, which means that various clients’ datasets may be highly imbalanced or biased reducing global model convergence. Second, clients’ hardware capabilities can vary, reducing the speed and consistency of local training. Third, intermittent or poor network connectivity, particularly in resource-constrained medical institutions or rural areas, might slow or restrict participation in global model updates. These limitations must be carefully examined when assessing FL systems for use in medical imaging workflows.

FL is important for more than just data privacy; it is also compatible with IoT-based healthcare solutions.

In the article written by Saadat Hasan et al. [

29], the research involves comparing the performance of four DL models, namely ResNet50, VGG16, AlexNet and a CNN composed of 4 Convolution, Max-Pooling and 2 Dense layers. The database used was “Chest X-ray (COVID-19 & Pneumonia)” [

30], from Kaggle, and for this pneumonia detection application, the COVID-19 images were removed from the training and testing sets. Each model was trained several times to adjust the parameters (learning rate, optimizer, number of epochs), and the complexity of the models was managed by adding or removing some layers that com- posed the proposed neural architecture. The best results were obtained for VGG16, with an accuracy of 90.6% on the test set, a precision of 94%, and a recall of 93%.

Amer et al. [

31] used the same database for image classification and tested the following pre-trained architectures on the ImageNet dataset: AlexNet, DenseNet, ResNet50, Inception, and VGG19. In an FL system, the 5 architectures obtained the following accuracies on the test dataset: ResNet-50 has 93%, DenseNet has 91%, AlexNet and VGG19 have 51%, and Inception has 50%.

In the article written by Judith S’ainz-Pardo et al. [

20] a custom CNN with the following characteristics is proposed: 5 Conv2D layers, 5 BatchNormalization, 5 Max- Pooling2D, 4 Dropout layers, 1 Flatten, and 2 Dense layers for the classifier. The study was conducted on the images obtained from [

20], and the performances were evaluated for three and ten clients, highlighting the benefits and challenges of each tested case. Additionally, cases where some clients leave or join during the data training phase or experience connectivity problems were also tested. After all the tests, it was observed that it is more convenient/effective to apply more rounds than training epochs of the model. This approach achieves good accuracy while reducing computation time. The accuracy obtained for 10 epochs for 3 clients was 80%, and for 10 clients it was 72%.

The article by Alhassan Mabrouk et al. [

32] proposes a solution that combines FL with eight CNN models (DenseNet169, MobileNetV2, Xception, InceptionV3, VGG16, ResNet50, DenseNet121, and ResNet152V2) through ensemble learning. A local ensemble model shared with a central node is created using the best two local models. The ensemble models are aggregated to obtain a global model. These steps are repeated until no further improvements are observed in the best local models. An accuracy of 96% is achieved using this approach.

Building on these foundations, our study simulates an FL framework for pneumonia detection from chest radiographies, aiming to assess its feasibility and performance under realistic constraints. The model is designed as a modular, privacy-preserving component suitable for integration into distributed IoT platforms.

2.3. Smart Healthcare Systems and Modular AI

IoT technology integration in healthcare has produced connected systems that can continuously and in real-time monitor patients’ behavioral and physiological parameters [

33]. These architectures use distributed sensors, including biomedical instruments, wearable technology, and ambient monitors, to gather multimodal data, such as activity, temperature, respiration, and vital signs. Particularly for vulnerable groups like patients with PD, AD, or MS, where early detection of complications like pneumonia is vital, these data streams provide context-aware decision support in both hospital and home settings. A paradigm shift from episodic care to proactive, individualized healthcare is represented by sensor-based health monitoring.

Several approaches have been proposed to embed AI in IoT-based respiratory health monitoring. Kelvin-Agwu et al. (2023) introduced a wearable device powered by AI that can detect respiratory problems early on, such as pneumonia and COPD, by continuously monitoring oxygen levels and lung function [

34]. Thanveer et al. (2023) looked into remote patient monitoring systems that use IoT technology, highlighting how FL helps with privacy-preserving distributed training across both edge devices and cloud servers [

35]. In a home-based ambient-assisted living context, Zieni et al. (2025) developed IoT sensor networks capable of discreet, continuous collection of multimodal physiological data and discussed integration constraints related to privacy, interoperability, and scalable deployment [

36]. While these systems show promising accuracy, they often rely on centralized data pipelines and lack modular AI deployment flexibility. Most are built as monolithic architectures that are hard to scale, validate, or adapt to new conditions or user profiles.

In contrast, the solution provided in this research focuses on modular deployment, privacy protection, and architectural integration into realistic IoT frameworks. Using FL, the pneumonia detection model can be trained locally on different devices or sites like clinics, rehab centers, or smart homes, without sending patient data to a central server. Unlike traditional centralized systems, the FL model functions as a standalone AI component that can be easily integrated into existing data collection and analysis workflows alongside other analytics tools. Its lightweight design and ability to handle diverse data make it ideal for deployment in resource-limited IoT environments. The design aligns with real-world system development practices, as exemplified by ongoing work on the NeuroPredict platform, where modular AI components are envisioned as integral parts of a flexible, multi-layered monitoring architecture.

The NeuroPredict platform, which collects multimodal data from wearable and ambient sensors, is one example of such an architecture. It is meant to support modular analytics components, including task-specific AI models for risk prediction, anomaly detection, and decision support [

37,

38]. The pneumonia detection module suggested in this study is conceptually similar to this architecture, both in its modular design and compatible with privacy-preserving computation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing Pipeline

3.1.1. Dataset Characteristics and Limitations

The dataset we chose to work with contains a large set of CXR images and was downloaded from Kaggle [

30]. This dataset contains binary labels (‘Normal’ and ‘Pneumonia’) and does not differentiate between pneumonia subtypes such as bacterial, viral, fungal or atypical pneumonia. While this binary classification task is suitable for feasibility evaluation of an FL framework, it does not fully reflect the complexity of real-world clinical diagnosis. The CXR images from this dataset are anterior–posterior, meaning that the X-ray beam enters the body from the front (anterior) and exits through the back (posterior). The images are in JPEG format and have different dimensions (for example, 1782 × 1434, 1570 × 1164, etc.), but most of them have a high resolution (over 1000 pixels both in width and height). Their sizes range from 100 KB to 500 KB approximately, and they are labeled into two classes: normal and pneumonia. Some randomly selected images from the dataset are shown in

Figure 2.

The Chest X-Ray dataset from Kaggle was chosen because it serves as a standard for pneumonia detection tasks and provides a publicly available, well-annotated image corpus that is appropriate for comparison and experimental reproducibility. It can simulate FL without requiring high-throughput infrastructure thanks to its controlled format and relatively small size.

The original dataset contains 5856 images in total, which have been pre-split into training, testing, and validation sets (a graphic representation of the class distribution can be seen in

Figure 3):

Train: 5216 images, 1341 normal, 3875 pneumonia;

Test: 624 images, 234 normal, 390 pneumonia;

Validation: 16 images, 8 normal, 8 pneumonia.

3.1.2. Implementation Environment and Tools

The most important technologies used in this research are:

Python version 3.10.12: This was the programming language used to develop this research.

TensorFlow version 2.15.0: It is an open-source framework that provides a solid and easy-to-use environment for ML applications.

Keras version 2.15.0: Keras allows the user to implement deep learning models in a high-level way.

CUDA version 12.2: Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) was a key tool in the development of this research, since the training of DL models on the central processing unit (CPU) would have been virtually impossible.

Pandas version 2.1.1, Numpy version 1.24.4: Used for the manipulation of different collections such as arrays or dataframes.

Matplotlib version 3.7.2: The main library for plotting the results of the clients and the global model.

Sklearn version 1.2.2: Used for generating the confusion matrices and the classification reports.

The research presented in this paper was developed on the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL2), due to the flexibility and usefulness of the Linux terminal. The specifications of the physical machine used for testing and implementing are as follows: Lenovo Intel i7-12700H CPU with 14 cores and 20 threads, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 Laptop GPU 8 GB, 32 GB RAM (Shenzhen, China).

In order not to be forced to store the high-resolution X-Ray images into memory, in our implementation we are using the ImageDataGenerator provided by Keras. This powerful tool can take a directory or a DataFrame containing image file paths as input and load the raw data of the image into memory only when it is required (in our case, only training and evaluation). The image data generator also allows for applying transformations to the image on the fly, which was used during dataset augmentation and when training the models.

3.1.3. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

All CXR images were resized to ensure consistent input dimensions and computational efficiency across clients in the federated setup. Images were resized to 150 × 150 pixels for the CNN model and to 224 × 224 pixels for the VGG16 model pretrained on ImageNet, following the Keras implementation guidelines [

39]. For VGG16, the keras.applications.vgg16.preprocess_input function was applied.

To address the class imbalance present in the original dataset and to improve model generalization under federated learning constraints, training data were augmented using standard CXR image transformations. The augmentation pipeline included random rotation (±10°), width/height shift (20%), shear (0.2), zoom (0.2), and horizontal flip. These transformations were applied stochastically to generate additional samples, particularly for the minority class, thereby reducing the risk of client-level overfitting and improving robustness in non-IID scenarios. A sample of augmented images is shown in

Figure 4.

Augmentation was applied exclusively to the training set. The validation and test sets were left unchanged to maintain an unbiased evaluation of model performance. After augmentation, the dataset contained 8 381 images in total, distributed as follows:

Train: 6966 images, 3479 normal, 3487 pneumonia;

Test: 624 images, 234 normal, 390 pneumonia;

Validation: 791 images, 395 normal, 396 pneumonia.

3.1.4. Client Data Partitioning Scenarios

An important aspect of FL is how the data is split between clients and what class distribution there is in each client’s dataset. In this research, the FL setup was simulated on a single physical machine, rather than being deployed on actual distributed devices, due to feasibility considerations and the need for reproducibility. A simulated environment was selected primarily because of resource constraints and to ensure that the experiments could be easily replicated:

Distribution by size: We can choose before starting the simulation how much data to assign to each client. This represents its personal data, which will be used for local training and will not be shared with anyone. The data distribution is performed by specifying for each client a fraction of the total globally available data.

Class proportion on clients: After the client has received its dataset, we can specify the fraction of data to keep for each class.

Data size for training in a round: To control how much data each client uses in its local training in a round, we can specify what fraction of the local dataset (the one resulting after the class selection from the bullet point above) is to be used for training in a round. If there are 10 rounds and the fraction is 0.1, then the total local dataset will be split into 10 batches of size 10% of it, and the client will train in the first round on the first batch, in the second round on the second batch, etc. So in this case, the client will practically train on new data each round, which is a useful scenario for simulating a real-world use case in which the data influx is constant. If the fraction is, for example, 0.5, and the number of rounds is 10, then the client will train on 50% of its dataset in the first round, then on the other 50% in the second round, but starting from the third round, it will reuse for training the same batch used in the first round; the fourth round will use the batch from the second round etc.

Figure 5 illustrates a simulated scenario in which the training and validation data are partitioned and allocated to three distinct clients participating in the FL process. Each horizontal bar represents one client’s local dataset, segmented by class distribution. The internal class balance within each client’s local data repository and the percentage of the entire global dataset assigned to each client are the two main features of the visualization. This makes it possible to simulate both Independent and Identically Distributed (IID) and Non-IID scenarios, which accurately represent the variability that exists in the real world across various healthcare facilities. In practice, such heterogeneity can significantly impact model convergence and global performance.

3.2. Model Architectures

The choice of model architectures in this study was motivated by deployment feasibility in realistic FL scenarios. Although more complex architectures such as EfficientNet, DenseNet, or Vision Transformers [

40] have demonstrated superior performance on chest radiography classification tasks, they require significantly higher computational resources and memory, making them less suitable for edge deployment in federated systems. Therefore, we selected a lightweight CNN architecture and the VGG16 model as a transfer learning baseline in order to balance diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency at the client level.

3.2.1. Baseline CNN Model Design

The CNN used in our experiments (

Figure 6) has 18 layers. A rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation layer, a max pooling layer with a pool size of 2 × 2, and a batch normalization layer come after each of the three 2D convolutional layers. By choosing the highest value from each feature map, the max pooling layer shrinks the feature maps’ dimensions, and the batch normalization layer normalizes the combined features for the subsequent convolutional layer. Max pooling thus decreases the computational load of the network, while normalizing stabilizes training and helps to preserve consistency. The next layers are the ones used to classify the input. The Flatten layer flattens the input into a vector with one dimension, while both Dense (fully connected) layers combine all features detected by the convolutional blocks. A Dropout layer of 0.5 (meaning 50% of the neurons are ignored) before each Dense layer forces the network to not rely too much on specific features, which prevents overfitting [

41]. The loss function used is binary cross-entropy, and in most experiments, Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) was the chosen optimizer.

3.2.2. Transfer Learning with VGG16

In Transfer Learning (TL), a model uses the knowledge learned from a task in order to generalize better for another one, which could be different. That implies using the weights of a model trained on a particular dataset on other data, which is similar in nature. This method is used if both tasks are related (image classification, for example) and if there is not enough labeled data to train a model from zero. Thus, an already existing network that was trained on massive amounts of data could more easily adapt to the new task.

For this task, we are using the pre-trained VGG16 [

42] model, which is a CNN with 16 layers that has been trained on ImageNet, a massive database containing over 14 million images belonging to thousands of classes. The VGG16 model was chosen as it demonstrated superior performance compared to other architectures, as reported in [

43,

44]. This can be attributed to VGG16’s simpler and more homogeneous architecture.

Since ImageNet is a database containing colored images, when training the VGG16 model, we need to convert the X-rays from grayscale to RGB. This is achieved using the ImageDataGenerator from Keras. First, we load the VGG16 architecture with the pre-trained weights from the ImageNet dataset, excluding the fully connected layers from the top of the model (include_top = False). Afterwards, we freeze the pretrained layers because we do not want their weights to be updated during the training (since we would lose the already known features). After putting the input through the pre-trained VGG16 layers, we use a GlobalAveragePooling2D layer to reduce the dimensions to a single vector for each feature map. This is followed by a Dense layer and a Dropout to prevent overfitting. The final Dense output layer with the sigmoid function is used for binary classification.

3.3. Federated Learning Setup and Training Workflow

The development of the federated learning system in this study was guided by four primary objectives:

Data privacy and security: to ensure that no actual data is transmitted between participating institutions, preserving patient confidentiality;

Diagnostic performance: to enable accurate detection of pneumonia in CXR images, with emphasis on minimizing false negatives;

Scalability: although the current setup involved only 3 to 10 simulated clients, the architecture is intended to support larger-scale deployments in real-world scenarios. Future work will address extensive scalability testing under broader network and client diversity conditions;

Robustness: to maintain performance despite class imbalance or data heterogeneity across clients, reflecting real-world variability in medical datasets.

Our general workflow is defined in several main steps:

At the beginning of the FL simulation, the images from the dataset are loaded into memory, and then, based on the set configurations, they are distributed to each client. In this way, each client has its own local set of data, which will be used for training and not shared with anyone else. Based on the model chosen in the configuration (CNN or VGG16), each client receives a different instance of the model, with an optimizer and a learning rate (both are the same across all clients), which will be trained locally on its personal dataset each round. The clients’ models are completely independent from each other; the only aspect that remains the same is the architecture. The global model is also initialized in this step. All clients are using the same model architecture in order for the weight aggregation to be possible.

During the training phase, the simulation runs for the number of communication rounds specified in the configuration. A round consists of the following steps:

Assign data used for local training in the current round: Based on the simulation’s configuration, the client can either use the same data for training or have different batches each round. In this step, the client’s data generator is updated to point to the data the client uses for training in the current round.

Local training: Now, the clients train their local models using the data given to them in the current round and with the configured number of epochs. After training, each local model is evaluated on the global test set, and the resulting metrics are stored for visualization at the end. In this way, we can record the clients’ performance across rounds.

Aggregation: Once all the clients have finished their local training, their model weights are aggregated using Federated Averaging (FedAvg), which computes an average of the weights of all clients. The result of the aggregation represents the global model’s weights for the current round. This aggregated model is now evaluated on the global test set, and the metrics are stored in order to be able to observe the global model’s performance evolution across rounds.

Update the clients’ local models: The clients’ local models receive the aggregated weights from the current round. In the next round, they will start their training from these new weights.

After the simulation ends, the system displays the metrics it collected throughout the training process using classification reports.

Since the main aim of this research was to simulate an FL setting and implement its basic principles, we have opted for an approach in which the clients are represented as class instances and the server that aggregates the client updates is the main process.

This implementation has two main advantages. Firstly, it is hardware- and time-efficient and focuses on the sole aspect of simulating a correct FL scenario. Secondly, the implementation dependencies (which in Python are not easily managed) are the same as the ones required for a traditional ML implementation.

We have implemented a class that stores a list containing the clients used in the simulation. The privacy aspect of the client’s data is handled by having a different data loader (Keras’s ImageDataGenerator) for each client.

It is important to emphasize that the FL configuration mentioned above is simulated in a centralized setting by simulating distributed clients through sequential training on a single physical machine. Although this method is common in FL research for controlled benchmarking, it ignores important elements of FL deployments in the real world, like client dropout, hardware heterogeneity, communication latency, and asynchronous updates. Therefore, rather than serving as a performance metric for clinical integration, the results reported here should be viewed as a proof-of-concept validation of architectural viability and model behavior under distribution constraints.

3.3.1. Data Distribution Policies

To distribute the original training and validation datasets among the clients, a function is employed that splits the initial dataframes based on a specified fraction. To guarantee that class proportions are maintained across the resulting subsets, the data is shuffled before splitting. Because a fixed random seed is used for this shuffling, the results are guaranteed to be repeatable. Each client receives a list of dataframes corresponding to the images it will use for training during each round. An equivalent procedure is applied to the validation data, and both sets are subsequently used in the FL process.

The configuration of an FL simulation in our system is defined through a structured set of design choices that govern various aspects of the training process. Each simulation scenario begins by specifying how the dataset is distributed among participating clients, how the local training is carried out, and how the class balance is handled within each client’s dataset.

For example, in a typical setup with three clients, each one may be assigned an equal share of the dataset, such as 20% per client, while the remaining data can be excluded or redistributed as needed. The number of training epochs executed locally by each client during each communication round is also defined at this stage, as is the volume of data processed in each step of training.

Instead of training on the entire dataset at once, clients are sometimes set up to use only a subset of their local dataset each round. This method enables clients to train incrementally over several rounds, simulating real-world scenarios where new data arrives gradually.

The configuration also allows for specifying the proportion of different classes within each client’s local dataset. For example, one client might be assigned a balanced distribution of cases, another a majority of normal cases, and a third a majority of pneumonia cases. This configuration makes it possible to simulate data that is not uniformly distributed, which captures the bias and variability frequently found in actual clinical settings.

Each client additionally maintains a track of validation performance to increase training efficiency and avoid overfitting. If no improvement is observed after a predetermined number of iterations, local training may be stopped early.

3.3.2. Federated Learning Implementation

Before the simulation begins, the FL application is initialized, and both the global model and individual local models for each client are instantiated. This setup establishes the necessary architecture for distributed training across clients.

At the start of each simulation round, each client is provided with dedicated data generators for training, validation, and testing batches. The test set remains constant and is not split across rounds, as client performance is consistently evaluated on the global test set to ensure a comprehensive and comparable performance assessment throughout the simulation.

Once the data generators are assigned, local training commences independently on each client. To improve training efficiency and model generalization, two key callbacks are utilized: EarlyStopping, which halts training if the validation loss does not improve after a predefined number of epochs (5), thereby mitigating overfitting; and ModelCheckpoint, which stores the model weights corresponding to the epoch with the lowest validation loss. After local training concludes, the best-performing weights are reloaded into the client’s local model.

Following the completion of local training by all clients, model parameters are aggregated using the FedAvg algorithm. The resulting aggregated weights are assigned to the global model and stored in a history structure for subsequent evaluation. Additionally, each client’s performance on the global test set is recorded for the current round, and the local models are updated with the newly aggregated global weights in preparation for the next round of training.

In our implementation, we employ FedAvg as the aggregation strategy for client model weights due to its demonstrated effectiveness even in non-IID data settings [

7]. This method computes the global model weights as the average of the locally trained weights from each client.

Specifically, the aggregation process begins by scaling each client’s weights by a corresponding scaling factor. In the standard FedAvg implementation, all clients are assumed to contribute equally, and therefore each client is assigned the same scaling factor, calculated as 1/N, where N is the total number of clients. This ensures that the global model reflects an equal contribution from each participant. For instance, in a system with three clients with local weights w

1, w

2, and w

3, the global model weights w

global are computed as follows:

During the aggregation process, the client weights are first individually scaled. Then, for each model layer, the corresponding scaled weights from all clients are summed to obtain the aggregated weights for that layer. This is performed in an iterative manner, layer by layer, ensuring consistent integration of updates across all model parameters.

3.3.3. Simulation Parameters and Client Settings

A number of client-side and data distribution parameters were set up in the FL simulation environment to mimic real-world healthcare situations while guaranteeing scalability and reproducibility. Depending on the experiment, the number of FL communication rounds varied among simulations, but the most common values were 10, 20, and 50.

To assess the FL framework’s scalability and adaptability under growing federation sizes, simulations were run with 3, 5, and 10 clients. This variation makes it possible to examine the effects of the number of participating institutions (such as clinics or hospitals) on the convergence of the model. While larger federations simulate wider deployments across regional or national networks, smaller federations replicate early-stage collaborations between a small number of centers.

A full participation strategy was used, where all clients synchronously engaged in every communication round. In order to simplify experimental control and enable more transparent analysis of the effects of data distribution and model updates, this synchronous setting—which is equivalent to the original FedAvg protocol—was selected. Full participation acts as a baseline for performance evaluation, even though client availability may fluctuate in real-world situations.

Each client conducted local training for 5 epochs per communication round. This value was selected as a compromise between local convergence speed and communication efficiency. It also ensures that local overfitting is limited while providing sufficient model updates per round.

A batch size of 32 was used across all clients. Both the Adam optimizer and SGD were tested. Although Adam is known for faster convergence in centralized settings, SGD was chosen as the default due to better stability in the federated context, as observed in preliminary experiments. A fixed learning rate of 0.01 was used during local training for all clients. The learning rate remained constant across communication rounds.

All clients were simulated as class instances within a shared Python environment, with equal access to computational resources. Hardware heterogeneity was abstracted to focus on algorithmic behavior and data-driven performance differences. This simplification also facilitates fair comparisons across clients and aligns with prior FL simulation practices.

The global dataset was partitioned using a custom Python function that ensures both reproducibility and controlled variability. A fixed random seed was used for shuffling before allocation to guarantee consistent results across different simulation runs. To reflect the spectrum of data homogeneity in healthcare systems, two distribution paradigms were implemented: IID and non-IID. As a performance baseline, this idealized situation provided information about the model’s upper-bound accuracy and convergence potential in ideal circumstances. The non-IID setup, on the other hand, involved assigning datasets to distinct clients with different class imbalances. For instance, one client was given 80% pneumonia and 20% normal cases, while another client was given the opposite distribution. A third client might have received a fully balanced subset. This setup was designed to simulate realistic conditions in which demographic and diagnostic variability exists across healthcare institutions. The choice of the 80/20 ratio was not based on a specific clinical study but was selected heuristically to simulate a clearly imbalanced scenario.

For clarity and reproducibility, the main hyperparameters used in all federated simulations are summarized below:

Optimizer: SGD (learning rate = 0.01, momentum = 0.9).

Loss function: binary crossentropy.

Initialization: He normal initialization for all convolutional and dense layers.

Local training epochs per round: 5.

Batch size: 32.

Early stopping: patience = 5 (based on validation loss).

Model checkpoint: best local weights saved each round.

Federated rounds: 10.

Aggregation algorithm: FedAvg (equal client weighting).

Batch-fraction usage: 0.1 or 0.5 depending on the scenario (as described earlier).

Train/validation split per client: proportional to local dataset size (90%/10%).

Test set: global held-out test set, identical for all configurations.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

In our experiments, we evaluated the performance of the shared global model after the final round of FL using metrics such as accuracy (2), F1-score (3), precision (4), recall (5), and loss. However, because in some cases the performance of the global model degraded in the last rounds, we also considered its maximum accuracy during the entire process and the maximum accuracy for each client as well. The F1-score is useful when there is class imbalance or when both types of errors carry significant clinical consequences. In Equation (2), TP means True Positives, TN is True Negatives, FP is False Positives, and FN is False Negatives:

TP—patient has pneumonia, and it was detected correctly;

TN—patient does not have pneumonia, and the X-Ray image was classified by the model as normal;

FP—X-Ray was classified as pneumonia, but the patient is healthy;

FN—X-Ray classified as normal, but patient does suffer from pneumonia.

The test accuracies for both the global model and the clients are calculated on the entire test set in order to establish a clear understanding of how the system is converging. Although in real life a client would not have access to the entire test set, we considered that for the purpose of this simulation it would be more useful to have a solid view on the actual performance of a client. The evaluation on its local test set would not have been of great significance due to the small size of the test set.

Aside from the regular classification metrics for the model’s performance, we also consider how efficient the FL system is in different settings (equally distributed data between clients, unbalanced sample distribution, unbalanced class distribution on the client side, etc.). Thus, several aspects are relevant in our evaluation:

Scalability—the system should be extensible, and a higher number of clients should not reduce performance.

Communication Efficiency—less communication rounds means less overhead between the clients and the server. The faster the model converges, the better.

Computational Efficiency—ideally, the workload and resources required on the client side should be as small as possible.

Fairness—as the models used in the actual prediction are the ones locally stored in the clients, the differences between client accuracies must be minimal.

While Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) is often utilized in binary classification tasks, it was not included in this analysis since the original implementation only computed binary predictions rather than probabilistic outputs. As a result, AUROC could not be estimated consistently in the existing configuration, and its integration remains a potential upgrade for future study.

3.5. Case Study: Integration into Smart Healthcare Platforms

This section connects the federated training workflow described in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4 with its conceptual integration into the NeuroPredict platform, clarifying how the global FL model could operate as a modular AI component in a real-world IoT healthcare system.

The NeuroPredict platform is a digital health system built on IoT technology that constantly tracks and adjusts care for patients dealing with neurodegenerative diseases like PD, AD, and MS. The platform integrates heterogeneous data sources from electronic health records, behavioral tracking technologies, wearable and ambient sensors, and cognitive tests. A modular AI pipeline is used to analyze these inputs, allowing for condition-specific analytics, patient privacy security, and interoperability across healthcare settings.

From a systems standpoint, NeuroPredict has a layered architecture that includes a distributed sensing layer (smart environments, wearables), a secure gateway and local processing tier (home hub or clinical edge device), and a cloud-based analytics backend where modules are coordinated and updated. The platform’s AI modules are designed to manage specific clinical tasks and communicate with the main system through pre-established Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

The FL model described in this study is methodologically and structurally consistent with the platform’s modular design. Conceptually, the model serves as an independent AI microservice capable of learning from CXR data spread across institutions or care centers—without transferring sensitive medical images. Technically, the output of the federated learning procedure can be encapsulated as an independent diagnostic service, aligned with NeuroPredict platform’s architectural constraints as detailed below. From an integration standpoint, it satisfies several key technical constraints defined by the NeuroPredict infrastructure:

Data locality and privacy compliance: The FL model ensures data sovereignty and complies with laws such as GDPR by using local datasets at clinical nodes.

Edge-cloud compatibility: The model can be trained gradually on edge or local clinical systems, with aggregation handled by a coordination layer included into the platform’s backend.

Task-specific modularity: As a plug-and-play diagnostic unit, the model meets the architectural requirement for AI services to be decoupled and deployable independently.

Sensor-system alignment: Although trained on CXR data, the model can be fed input from radiological imaging modules within the NeuroPredict ecosystem. This is especially useful for routine or remote imaging in community clinics.

Clinically, pneumonia is a frequent and high-impact comorbidity in PD, AD and MS, which justifies its selection as a conceptual integration scenario.

It is important to clarify that, as of the current work, the federated model has not been deployed within NeuroPredict. However, the platform was explicitly designed to accommodate such extensions, and this study defines the architectural and operational pathway for its future integration. By combining a technically mature FL diagnostic model with a real-world IoT health platform, we demonstrate a viable blueprint for extending modular AI across disease domains in sensor-based health systems.

While writing the paper, the authors used the generative AI tool ChatGPT-4o mini (Free)—powered by GPT-4o mini in order to ensure a better translation and language improvement. It was used to translate the initial versions of the text from Romanian to English and to provide assistance with minor grammar and style corrections. No text generation, data analysis, figure creation, or interpretation of results were performed using the AI tool. All the scientific content, results, and conclusions are attributed to the authors.

4. Experimental Results

This section presents the experimental results obtained from centralized and federated learning scenarios, using both baseline CNN and VGG16 architectures. The models were evaluated based on classification accuracy, F1-score, and loss. Several configurations were tested, including variations in optimizer, data distribution, number of clients, and use of pretrained weights. All experiments were conducted on a local workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU, as described in

Section 3.1.2. In all experiments, evaluation was performed on the same held-out test set, ensuring consistency across comparisons.

4.1. Centralized Training Results

Before using it in an FL setting, we first tested the performance of our CNN model in the centralized case. We performed two trainings. In one of them, the model uses Adam as optimizer and in the other one, SGD is used. This was also done to see what optimizer makes the model converge faster, since one of our aims in FL is to reduce the computational load on the clients (i.e., less epochs on each client). To prevent overfitting, the global test set was kept strictly isolated from all stages of federated aggregation and local training. Model hyperparameters were selected using only the training and validation partitions, and the test set was used exclusively for final evaluation. No form of test data leakage was introduced. To ensure consistency and comparability across all tests, the centralized and federated models were evaluated using the same global test set. All reported measures were obtained under the same testing settings, while the test set was totally isolated from any training or aggregation steps, preventing bias and ensuring methodological consistency. All centralized models were initialized using He normal initialization. Training was performed using both SGD (momentum = 0.9) and Adam (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999) to compare convergence stability. Early stopping with patience = 5 was used to prevent overfitting. Training efficiency is reported using wall-clock time rather than epoch count, since the latter does not reflect actual computational cost.

For comparison, the wall-clock training time for the centralized CNN model using the Adam optimizer was roughly 2 min and 10 s, but training with SGD took 4 min and 45 s under identical hardware and batch-size parameters. SGD had slightly higher ultimate accuracy (0.891 vs. 0.883), but its convergence was roughly 2.2× slower in real time. This trade-off was considered when selecting the optimizer for the federated setup, where computational efficiency and client-side stability are important factors.

Although SGD is usually used with a learning rate decay or techniques like ReduceLROnPlateau, we did not use them because we wanted to see how the optimizer fares with its default learning rate (the clients from the FL simulation do not train the local model for a large number of epochs).

The augmented dataset is split 90-10 between training and validation. The training configuration is as follows:

The callbacks used follow the same approach as in the client’s local training. EarlyStopping stops the training if the validation loss does not improve for five straight epochs, which helps avoid overfitting. At the same time, ModelCheckpoint saves the model weights from the epoch with the lowest validation loss, making sure the best version of the model is kept.

Using the Adam optimizer, the CNN finished training early after 12 epochs, while training with SGD took 30 epochs. The results for test accuracy, F1-Score and binary cross-entropy loss are shown in

Table 1.

As we can see, SGD outperformed Adam by a very small margin (0.01 accuracy and 0.01 F1-Score difference), but it was more than twice as slow. Another observation is that the F1-Score is better for the pneumonia class than for the normal one. This can be related to the class imbalance from the initial dataset. Although new augmented images were generated for the normal class to balance the dataset, initially the pneumonia to normal image count ratio was 3:1, and the transformations applied during augmentation do not change features of the X-Ray, the base source image still being the reference.

A higher F1-Score for pneumonia, however, means that the model is performing better both in precision and recall for detecting cases of illness, so there are fewer false positives and fewer false negatives. We decided to choose SGD as optimizer for our FL system.

4.2. Federated Learning Performance

4.2.1. Independent and Identically Distributed Data

In this section, the goal is to test the scalability of our FL system; that is, to experiment what impact the number of clients has on the overall performance. Aside from that, it is also important to find out how the size of the dataset owned by each client influences the outcome. These effects are not uniform across all dataset sizes, and the FL system behaves differently when per-client data availability is very limited.

For these experiments, the data is distributed equally between clients, each client has the same number of samples. At the same time, there is an equal distribution of classes in each local client dataset, with half of the CXR representing pneumonia cases, and the other half being normal ones.

In order to see how the number of clients and the data size each influence the outcome, we performed runs for 3, 5, 10, 15, and 20 clients, and for each fixed number of clients, we varied the data size with 100, 175, 350, 700, and 1400 samples for training CXR on each client. The validation sets assigned are proportional to the training set size, being 20, 40, and 80. The optimizer used was SGD.

All runs from

Table 2 were done with 10 communication rounds and 5 epochs for the clients’ local training. Data refers to the training dataset size per client, Clients indicates the number of clients, F1S (N), Prec (N), Rec (N) are the F1-score, precision, and recall for normal images, F1S (P), Prec (P), Rec (P) are the F1-score, precision, and recall for pneumonia images, Final Acc represents the final global model accuracy, Loss indicates the final loss, and Max Acc shows the maximum global model accuracy achieved across all rounds.

Key takeaways after analyzing the simulation runs:

Data size effect: Increasing the local dataset size per client consistently improves the global model’s accuracy and F1-scores. However, the performance gains tend to saturate beyond 700 samples per client, suggesting diminishing returns when the local datasets are already sufficiently large.

Number of clients effect. The impact of increasing the number of clients depends strongly on the local dataset size. When each client holds very few samples (e.g., 100), adding more clients does not improve accuracy and may introduce variability during aggregation. For larger per-client datasets (≥350), performance becomes more stable and the benefits of additional clients are more visible.

Stability and convergence: While accuracy increases with the number of clients, the gap between Final Accuracy and Max Accuracy also becomes slightly wider, indicating a moderate variability in convergence as the federation grows.

Scalability: The FL system demonstrated stable scalability up to 20 clients without significant performance degradation, confirming that communication and aggregation mechanisms remain efficient in larger federations.

Optimal trade-off: The best balance between computational cost, communication rounds, and model performance was achieved for configurations with 10–15 clients and 350–700 samples per client.

4.2.2. Unbalanced Class Distribution Scenarios

We have seen that our application performs well in situations where the data is equally and identically distributed to the clients (i.e., all clients have the same number of images and classes are split 50–50 on the clients’ local datasets). However, it is easy to assume, especially for the use case discussed in this article, that there is a high chance for each client to have a different number of samples for each class. Some hospitals could have more CXR diagnosed with pneumonia than normal and others could be the other way around. Whichever the case, it is essential that clients with high class imbalance do not bias the global model and that the overall performance remains decent.

One important aspect to note is that a client can choose during inference (the process when the model is given data to be classified) to use either the local or the global model, depending on which achieves better performance. Thus, the purpose of this experiment is to see if at least one of these is good enough in such an unfavorable setting. For the simulations the following configurations are used:

Number of clients: 3;

Number of samples per client: Train: 700, Validation: 80;

Training time: 10 rounds, 5 epochs on client;

Optimizer: SGD with learning rate 0.01;

Aggregation method: FedAvg.

This scenario accounts for the situation where the class imbalance on each client is different. This scenario was considered in order to see how each client performs in relation to its data imbalance.

Three scenarios were simulated:

Balanced (50–50)—all clients have an equal proportion of normal and pneumonia images;

Moderate imbalance (40–60/60–40/50–50)—some clients have a majority of one class;

Severe imbalance (20–80/80–20/50–50)—one client has very few images of a class, another has a majority, and the third remains balanced.

The results in

Table 3 indicate that, even under severe imbalance, the global model maintains a decent performance. Local client performance varies more significantly, with clients having a minority of a class showing lower Final Accuracy. For example, in the scenario with severe imbalance, client C0 has only 20% pneumonia images and achieves Final Acc 0.625, while client C1, with only 20% normal images, reaches 0.766.

The F1-Score for pneumonia remains relatively stable across clients, showing that minority class performance can benefit from the global aggregation. This demonstrates that the FedAvg algorithm effectively allows clients to leverage information from other clients, improving individual performance even when local datasets are highly imbalanced.

Key takeaways from these simulations:

Increasing class imbalance affects local client performance, particularly for clients with very few samples of a class.

The global aggregated model remains robust, mitigating the negative impact of highly imbalanced local data.

FedAvg ensures that minority-class performance is not completely lost, demonstrating the collaborative benefit of FL.

Even severe imbalance does not prevent the global model from achieving reasonable performance.

4.3. Transfer Learning Performance with VGG16

The main benefit of transfer learning is that a pre-trained model could require less training samples in order to achieve the same or even a better performance than a normal model. For FL, data scarcity on the client side is one of the biggest challenges, since each client, although helped by the global aggregation, can only use its own data to increase its local model’s performance. Class imbalance is another important issue in this domain.

4.3.1. Centralized Training

As we have seen in the case of CNN, the optimizer has a significant importance in the training process and it is not an easy choice to make. In order to obtain an insight into what learning rate could work best for VGG16 (

Table 4), we conducted two experiments (SGD with learning rate 0.01, SGD with learning rate 0.001) with the following configuration:

Number of clients: 3;

Number of samples per client: Train: 700, Validation: 80;

Aggregation method: Federated Averaging;

Training time: 10 communication rounds, 5 client epochs;

Equal class distribution on clients.

We have chosen to try a smaller learning rate for VGG16 for two reasons:

Fine-tuning: Pre-trained VGG16 already has its weights trained on a very large dataset containing 1000 object classes, which leads to a very high possibility of it being already close to the new classes. A smaller learning rate prevents any aggressive changes in the weights, which could damage the known features.

Stability and overfitting: Modifying the weights by a smaller value generally reduces the chance of overfitting and can also prevent oscillations in the learning curve.

4.3.2. VGG16 Performance Under Class Imbalance

As seen in

Section 4.2., a class imbalance can determine irregular behavior in the FL process. Although one client performed well in spite of having a heavy disproportion between classes, the other two and the global model performed poorly. In order to tackle this issue, we have tried to use the pre-trained VGG16 in that same specific scenario to see how it performs. Our results are shown in

Table 5.

In summary, the experimental results indicate that the FL system maintains a robust performance across different data distributions and client configurations. The pre-trained VGG16 architecture consistently outperformed the baseline CNN, particularly under class-imbalanced conditions. In addition, the VGG16-based architecture exhibits superior accuracy and F1-score in the centralized training setup, owing to its deeper convolutional layers and use of pretrained weights. However, this performance comes at the cost of significantly higher computational demand (~40 sec/round vs. ~15 sec/round) and memory usage compared to the lightweight CNN baseline. In a federated learning scenario with resource-constrained devices, this trade-off must be carefully evaluated. Despite this, the proposed system’s modular design and the availability of edge-optimized inference tools make the VGG16-based model a viable option for deployment, particularly when utilized in IoT systems powered by mid-range computing devices.

These findings indicate that incorporating such a model into IoT health platforms is viable, as long as the available computational resources allow for it. However, more testing in real-world situations will be required to see how well the model generalizes and performs in actual deployment scenarios.

5. Discussion

The technical results presented above place the proposed model not only as a performant AI solution for pneumonia detection, but also as a prototype that aligns with the architectural logic and deployment philosophy of next-generation IoT platforms like NeuroPredict, which are currently evolving toward modular, privacy-compliant medical intelligence. In the same time, it should be taken into consideration the fact that the FL model simulation was performed only in lab environment with virtual clients, as the model has not been integrated into the NeuroPredict platform yet. It is foreseen to be further improved after its testing into real clinic environments.

The novelty of this study lies in the experimental design, which systematically explores parameter variations that have been insufficiently addressed in previous research [

31,

32]. Unlike prior studies that focused mainly on model accuracy or architecture selection, our work investigates the impact of multiple factors, such as optimizer type (SGD vs. Adam), data partitioning strategies, number of communication rounds, client participation size (3–20 clients), and data distribution strategies (IID vs. non-IID).

5.1. Clinical Interpretation of Results

The experimental results reported in this study provide insights into the diagnostic reliability, flexibility, and practical limits of utilizing deep learning models for pneumonia detection in an FL setting. The model evaluations were carried out systematically across centralized and federated setups, employing both a proposed CNN architecture and a VGG16-based FL setup. The results were subsequently examined in a variety of data distribution scenarios, including class imbalance and varied client dataset sizes, to model conditions more closely related to those found in real-world decentralized healthcare settings.

In the centralized setup, the CNN-based model reached an F1-score of 92% for the pneumonia class—this is considered a strong performance benchmark in AI-assisted diagnostic tools. This level of accuracy is consistent with the performance range reported by previous deep learning models for CXR classification trained on similar datasets. Nevertheless, in addition to numerical performance, it is important to evaluate the implications of these findings within a potential clinical setting, especially when the target context involves vulnerable groups such as individuals with neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., PD or AD).

The F1-score, by definition, combines both precision and recall, making it particularly suited for evaluating medical image classifiers where both types of error (false positives and false negatives) have significant consequences. In this context:

An FN—incorrectly categorizing a pneumonia case as normal—can postpone the start of treatment, allowing the infection to advance without detection. This poses significant risks for neurodegenerative patients who may already have impaired lung function or limited ability to communicate, thereby heightening the chances of hospitalization, intubation, or even death.

An FP—incorrectly diagnosing pneumonia when the X-ray is actually clear—can result in overtreatment, including unnecessary antibiotics, further imaging tests, or hospitalization. Although arguably less perilous than false negatives, such mistakes impose psychological stress, escalate healthcare expenses, and lead to clinical inefficiencies.

In light of this, the model’s superior F1 performance for the pneumonia class (0.91) is clinically relevant, suggesting a high recall rate for detecting actual cases, while maintaining adequate specificity to avoid alarm fatigue. Additionally, these metrics align with the minimum thresholds observed in medical AI literature, where F1-scores greater than 0.85–0.90 are generally regarded as acceptable for prototype-level diagnostic tools meant for decision support instead of independent operation.

The baseline CNN also achieved reasonably good performance (F1 up to 0.92 for pneumonia, 0.84 for normal), but with more volatility across client-specific configurations in FL mode. When the models were deployed in a simulated federated learning environment, the average accuracy decreased slightly (to ~85%), which is expected given the non-IID distributions and reduced data access per client. Importantly, the F1-score advantage for pneumonia remained consistent even in these distributed settings. This indicates that the system prioritizes sensitivity to disease markers even under partial data visibility—a desirable feature when deployed in edge environments such as small clinics, local monitoring centers, or home-based care infrastructure. These findings, while scientifically strong, must be interpreted with clinical sensitivity. The clinical cost of a false negative in individuals with Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease can be fatal due to diminished physiological reserves and poor symptom reporting. False positives, while less harmful, can nevertheless result in unneeded treatments or hospitalizations, particularly in vulnerable individuals. Hence, while the model’s very good F1-score is comforting, application in neurodegenerative populations in the future would necessitate tuning for high sensitivity at the expense of some specificity. This is necessary for clinical safety in such vulnerable populations.

The proposed FL framework achieved competitive performance on the Kaggle CXR dataset, with VGG16 (FL) reaching an accuracy of 91.3%, F1-score of 0.91 for pneumonia, precision of 0.92, and recall of 0.90, while the baseline CNN (FL) achieved an accuracy of 89.1% and F1-score of 0.92 for pneumonia. These metrics confirm that the proposed architectures perform within the upper range of reported values for this dataset.

To contextualize these findings,

Table 6 comprises a comparative summary of recent federated and centralized approaches applied on the same Kaggle CXR dataset. For example, Amer et al. (2024) [

31] reported 93% accuracy using ResNet-50 in an FL setup; Kulkarni et al. (2022) [

45] obtained an AUROC of 0.88 with DenseNet121 (FL); and Mabrouk et al. (2024) [

32] achieved 96.63% accuracy with an ensemble FL approach combining multiple CNN models.

Compared with these works, our framework achieves comparable diagnostic performance while prioritizing practical deployability in IoT-based healthcare settings, highlighting its applied innovation and translational relevance beyond mere accuracy improvement.

Despite this encouraging performance, various restrictions must be considered when interpreting the results beyond a technical context. Training and testing were conducted on the entire publicly available CXR dataset with only images having labels “pneumonia” or “normal,” without finer-grained pathology labels, patient-level clinical information, or contextual clinical information. In addition, the dataset was not stratified for neurodegenerative patients, and therefore even though the introduced system is theoretically appropriate for these groups, the model has not encountered their specific imaging patterns. The training data does not include factors such as postural fluctuation, muscle rigidity, or pre-existing chronic lung alterations (all of which are typical in PD or AD), limiting the model’s immediate usefulness in such circumstances.

The FL environment employed here is a controlled simulation, not an actual multi-institutional deployment. The simulated clients are abstracted nodes with synthetic data partitions that operate on the same hardware instance. As a result, communication delay, client dropout, hardware heterogeneity, and privacy-preserving methods (such as safe aggregation and differential privacy) were not included.

From a systems perspective, these results mark a first technical milestone, demonstrating that a modular AI component for pneumonia detection can be trained and validated in a federated manner without requiring centralized data storage. This is consistent with recent advances in privacy-preserving AI for healthcare, particularly when applied to IoT-integrated remote monitoring platforms. However, any claims of clinical relevance must remain conceptual at this stage. Further work is required to validate performance on population-specific datasets, verify robustness across imaging devices and acquisition protocols, and implement the model in the context of interoperable digital health infrastructures with real-time feedback and alerting systems.

The current findings show that FL can be utilized to create image-based diagnostic models that are robust to data fragmentation and client heterogeneity. While performance is promising, particularly with the use of pretrained models, clinical translation is still dependent on extensive validation, regulatory approval, and integration into larger care workflows.

5.2. Clinical Relevance for Neurodegenerative Care

Pneumonia not only poses a significant threat to the health of individuals with neurodegenerative illnesses, but it is also a pivotal moment in their prognosis. A bout of pneumonia can hasten cognitive decline, worsen frailty, and raise disease burden. Pneumonia-related hospitalizations are among the most expensive in terms of healthcare costs, requiring acute care, prolonged antibiotic usage, and extensive discharge management.

Within neurodegenerative care, where pneumonia contributes substantially to morbidity and mortality, earlier detection and closer surveillance are clinically desirable. An FL-based pneumonia classifier, if prospectively validated and embedded into a broader monitoring platform, could contribute decision-support information for such patients, for example, by flagging suspected pneumonia episodes for clinician review. At present, however, this role remains hypothetical, as our experiments do not include neurodegenerative populations, longitudinal monitoring, or real-world deployment.

5.3. Conceptual Deployment Framework for Smart Healthcare Integration