Abstract

Quantized large language models are large language models (LLMs) optimized for model size while preserving their efficacy. They can be executed on consumer-grade computers without the powerful features of dedicated servers needed to execute regular (non-quantized) LLMs. Because of their ability to summarize, answer questions, and provide insights, LLMs are being used to analyze large texts/documents. One of these types of large texts/documents are Internet of Things (IoT) privacy policies, which are documents specifying how smart home gadgets, health-monitoring wearables, and personal voice assistants (among others) collect and manage consumer/user data on behalf of Internet companies providing services. Even though privacy policies are important, they are difficult to comprehend due to their length and how they are written, which makes them attractive for analysis using LLMs. This study evaluates how quantized LLMs are modeling the language of privacy policies to be potentially used to transform IoT privacy policies into simpler, more usable formats, thus aiding comprehension. While the long-term goal is to achieve this usable transformation, our work focuses on evaluating quantized LLM models used for IoT privacy policy language. Particularly, we study 4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit quantized versions of the large language model Meta AI version 2 (Llama 2) and the base Llama 2 model (zero-shot, without fine-tuning) under different metrics and prompts to determine how well these quantized versions model the language of IoT privacy policy documents by completing and generating privacy policy text.

1. Introduction

In today’s world, there has been a significant increase in the usage of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and this usage is expected to rise rapidly in the upcoming years [1,2]. IoT devices are designed to make our lives easier [3,4,5], but they can become a significant threat to the privacy of consumers [6,7,8,9] because IoT devices can collect personally identifiable information such as one’s name, age, email address, date of birth, and other types of data, such as sensor-based data (e.g., faces, sound) and metadata [10]. From the perspective of service providers, the privacy policies of IoT devices/services describe what type of information they collect, how long they retain this information, how they are going to use this information, and how they share this information with third parties [11]. While these documents are provided to users to let them know how their data/information is handled, past research shows that the users do not read the terms and conditions of the privacy policy notices and many times accept them blindly [12].

There has been a disconnection between the privacy policies’ documents and the comprehension of these policies by users [13,14]. First, the privacy policy language is vague, and it is very difficult for a naive user to understand the information [7]. Second, privacy policies of IoT devices keep changing regularly and users might not be aware of these changes [11,15]. Additionally, privacy policies for IoTs are very lengthy [11], and all the information is scattered, making it difficult for the consumers to find what they are exactly looking for [16]. Previous studies have attempted to address these issues by simplifying the language or restructuring the information in privacy policies [17]; however, these solutions have not fully leveraged the latest AI technologies. With the advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP), some of the issues regarding understanding privacy policy documents can be addressed. Among these new developments, large language models (LLMs) [18] have attracted great attention due to their ability to comprehend, analyze, and generate text.

Large language models (LLMs) can also be called Transformer Language models, and they are composed of billions and trillions of parameters [18] which are trained on considerable amounts of text data [19]. Examples of large language models include GPT-3 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) [20], which is known for its ability to generate coherent and contextually relevant text on a wide range of topics and is widely used for applications such as content creation, language translation, and summarization. Next, PaLM (Pathways Language Model) [21] is distinguished by its pathway-based training approach, enhancing its multitasking capabilities and excelling in tasks that require reasoning, such as problem solving and code generation. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [22] revolutionized the field of natural language understanding by its use of bidirectional training, significantly improving performance on tasks like sentiment analysis and question answering. RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach) [23] is an optimized version of BERT that adjusts key hyperparameters, which allows it to achieve better performance on a wider range of language-understanding benchmarks. Galactica [24], focused on scientific knowledge, aids in digesting and summarizing large volumes of academic literature and technical documents. LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) [25] is known for its efficiency and scalability and is utilized for a broad array of applications, including assisting in generating and summarizing complex documents. These models can solve complex problems like text generation, question answering, and code generation, among others [18].

Using LLMs to enhance the understanding and accessibility of IoT privacy policies requires the evaluation of the performance of LLMs in terms of modeling the language specific to these types of documents. This study specifically addresses gaps identified in existing research by employing quantized LLMs to generate privacy policy language (i.e., privacy policy texts). Quantization is the process of reducing an LLM’s size while preserving its efficacy, thereby optimizing computational resources without a substantial compromise in performance [26]. Recently, some works have researched the use of LLMs to analyze privacy policies [17,27,28]. However, these works focus on non-quantized LLM models. In this work, our aim is to assess how effectively 4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit quantized versions of the Llama 2 model can model the language of IoT privacy policies. We explore the performance of these models under various metrics and prompts, and we compare them with the base Llama 2 model without quantization. We attempt to answer the following question:

RQ1: How do different quantized versions of the Llama 2 model behave to generate IoT privacy policy language by completing incomplete privacy policy texts?

2. Related Work

In this section, we present a review of related works in LLMs and an analysis of privacy policies and IoT devices.

2.1. Large Language Models

Neural networks are currently used to analyze unstructured and complicated data types like text [29], audio [30], video [31], and images [32], among others. While there are many neural network models used for different purposes, there are two types of neural networks, namely, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [33], which have been widely used in the last decade, fueling the advance of AI. CNNs are used to process images and attempt to mimic how the human brain processes vision [32], while RNNs are used for processing time-indexed data, including text data [29]. However, in the context of texts, RNNs cannot handle large amounts of text data, and they are hard to train [34]. To overcome these drawbacks, the Transformer architecture was introduced by Google in 2017 [35]. The transformer architecture consists of two neural networks, called an encoder and a decoder, which possess a mechanism called self-attention to allow a neural network to understand a word and its context [35]. Self-attention also helps neural networks to differentiate words, recognize parts of speech, and identify the word’s tense, among other actions [35].

LLMs are built upon the transformer architecture [35]. They have the capacity to scale language models to hundreds of billions of parameters [18] and are trained on large amounts of text data [19] to be used for several tasks, including text generation, text summarization, question answering, and code generation, among others [18]. Examples of large language models include GPT-3 [20], LLaMA [25], and BERT [22]. Table 1 summarizes different LLMs; their release dates, sizes, and numbers of pretrained tokens; and their capabilities.

Table 1.

Overview of Large Language Models and their capabilities.

Table 1.

Overview of Large Language Models and their capabilities.

| Model | Release Date | Size in Parameters | Number of Tokens (Pretrained) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT–3 [20] | May 2020 | 175 billion | 499 billion | Language understanding, sentiment analysis, and Text Generation. |

| GPT–4 [36] | Mar 2023 | - | 13 trillion | Text generation, text translation, and natural language understanding. |

| BERT [22] | Oct 2018 | 345 million | 3.3 billion | Text summarization, question answering, and chatbot. |

| CoHere [37] | Jun 2022 | 52 billion | - | Text generation, text summarization, and text classification. |

| Ernie 3.0 [38] | Jul 2021 | 10 billion | 375 billion | Natural language understanding and text generation. |

| Falcon 40B [39] | May 2023 | 40 billion | 1 trillion | Text generation and machine translation. |

| LaMDA [40] | Jan 2022 | 137 billion | 1.56 T words, 168 billion tokens | Text summarization and question answering. |

| LLaMA [25] | Feb 2023 | 65 billion | 1 trillion | Text generation, text summarization, question answering, and language translation. |

| Llama 2 [41] | Jul 2023 | 70 billion | 2 trillion | Text generation and language translation. |

| StableLM 2 1.6B [42] | Jan 2024 | 1.6 billion | 2 trillion | Language understanding and text generation. |

| PaLM [21] | Apr 2022 | 540 billion | 768 billion | Arithmetic reasoning, code generation, and language translation. |

| PaLM 2 [43] | May 2023 | 16 billion | 3.6 trillion | Arithmetic reasoning, classification, question answering, translation, and natural language generation. |

| BARD [44] | Mar 2023 | 137 billion | - | Question answering, text generation, and language translation. |

| T5 [45] | Oct 2019 | 11 billion | 1 trillion | Text summarization, language translation, and sentiment analysis. |

| BLOOM [46] | Nov 2022 | 176 billion | 350 billion | Machine translation, text generation, and text summarization. |

| Pythia [47] | Apr 2023 | 12 billion | 300 billion | Question answering. |

| Gopher [48] | Dec 2021 | 280 billion | 300 billion | Text generation, machine translation, and question answering. |

| AlexaTM [49] | Aug 2022 | 20 billion | 1.3 trillion | Text generation and summarization, machine translation, and chatbot. |

| GLaM [50] | Dec 2021 | 1.2 trillion | 1.6 trillion | Machine translation, text completion, dialog generation, natural language inference, and document clustering. |

| Chinchilla [51] | Mar 2022 | 70 billion | 1.4 trillion | Text generation and chatbots. |

Quantization is a technique to compress a model by converting the weights and activations within an LLM from a high-precision data representation to lower-precision data representation [52]. There are two types of LLM quantization: post-training quantization (PTQ) and quantization-aware training (QAT) [53].

Post-training quantization (PTQ) refers to a model compression technique to quantize neural networks directly after training without fine-tuning, and it does not require the entire dataset used for training [54,55,56]. PTQ is simpler and easier to implement than quantization-aware training (QAT), as the latter requires a subset of the training data [57]. However, PTQ might lead to a decrease in the model’s precision and its accuracy due to the coarser representation of the model’s weights [57]. Quantization-aware training (QAT) involves adjusting the models by fine-tuning them specifically to accommodate data quantization during the training process [58]. QAT incorporates the process of converting weights, such as calibration, range estimation, clipping, and rounding, within the training period. This leads to enhanced performance of the model, but it requires more computational effort [58].

While microcontrollers like the ESP32 and popular embedded computers used for IoTs, like the Raspberry Pi, do not have enough memory or processing capability necessary to store and execute quantized models (as of 2024), there are other IoT devices/platforms available in the market, such as the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin and Jetson NX Orin series, that can run these models, as they have at least 32 GB RAM in memory and embedded tensor/GPU acceleration. Based on the evolution of computing in the last decades, we believe that many consumer devices and computers will be able to execute quantized models at the edge of the Internet in the upcoming years.

2.2. Privacy Policy of IoT Devices

Privacy policies are explanations of how an organization plans to handle user data [11]. They are also referred to as privacy statements or privacy notices. They serve as legal agreements between consumers and organizations, with the goal to protect/give certain type of digital rights on the use, processing, and disposition of data [11]. The details of consumers can be collected by an organization in multiple ways. For example, when a user purchases a smart phone, the consumer is asked for details like their name, age, date of birth, and address (among others) [10], and sensors embedded in IoT devices are used which collect identifiable data, such as biometric data, location data, and metadata (e.g., amount of Internet traffic) [59]. All these data can be valuable to businesses but can potentially generate privacy concerns for the user [6,7,8,9]. The privacy policy statements describe how companies collect the information, what type of information they collect, why they collect the personal information, for how long they intend to store the information, how they interact with third parties to collect personal information, and how they intend to use this information [11].

All the details about users’ data management may not be described clearly in privacy policies, and the consumers are expected to read them thoroughly and then decide whether to accept the privacy policy or not. Many users do not read privacy policies due to several reasons [12], including their extensive length [7] and the lack of clear language used [11]. Additionally, privacy policies keep changing regularly, and consumers in many cases are not promptly informed about the updated policies [11,15]. Finally, the information in the privacy policies in many cases is not organized, thus making it difficult for consumers to search for what exactly has changed and how these changes affect them [16]. As a result, users do not have a proper understanding of when/how their data are being collected and shared with third-party companies.

Usable privacy has been studied as an approach to make privacy policies understandable using machine learning, data processing, and legal analysis [60]. Most of the related work in this area has focused on enhancing the readability and usability of privacy policies through traditional NLP techniques, user interface improvements, and deep learning [13,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. Using LLMs for usable privacy is a recent area of research. In this area, the works of Tang et al. [27], Pałka et al. [17], and Rodriguez et al. [28] have evaluated the use of LLMs in privacy policies. Particularly, the work of Tang et al. [27] focused on the development of a chatbot called PolicyGPT, based on ChatGPT, to classify privacy policies. Pałka [17] evaluated the use of ChatGPT 3.5 and 4 to answer questions regarding privacy policies, and the work of Rodriguez et al. focused on the use of ChatGPT; Llama 2; and an in-house, fine-tuned version of ChatGPT to classify privacy policies [28]. However, neither of these works evaluated quantized models in the modeling of privacy policy language, which is the focus of our work. Table 2 presents a summary of related works in the evolution of IoT devices, challenges in understanding the privacy policies of IoT devices, usable privacy, and how artificial intelligence (AI) is used to analyze them.

Table 2.

Summary of research on IoTs, usable privacy, and AI analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of research on IoTs, usable privacy, and AI analysis.

| Reference | Year | Title | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | 2010 | The Internet of Things: A survey | Provides a detailed analysis of the usage of IoT devices and their applications in the real world. |

| [60] | 2013 | The Usable Privacy Policy Project | Reviews how to make web privacy policies more understandable for users by using natural language processing, crowdsourcing, and other technologies. |

| [62] | 2014 | Privee: An architecture for automatically analyzing web privacy policies | Presents an architecture to enhance privacy policy transparency by analyzing the privacy policies using crowd sourcing and classification tools. |

| [74] | 2014 | Wearables: Fundamentals, advancements, and a roadmap for the future | Reviews the evolution of wearable technology, highlighting its past developments and prospects. |

| [75] | 2015 | Internet of things: A survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications | Presents a review of protocols, enabling technologies, the role of sensors, and actuators of IoT devices. |

| [63] | 2016 | The Creation and Analysis of a Website Privacy Policy Corpus | It presents a review of development of a corpus comprising 115 privacy policies with detailed annotations for 23,000 data practices. The study enables the automation of extracting relevant information from these documents. |

| [76] | 2017 | A survey of wearable devices and challenges | Reviews the usage of wearable devices, their functions and challenges, and the future trends. |

| [77] | 2017 | Future of IoT networks: A survey | Provides an in-depth analysis of IoT networks and their future developments. |

| [64] | 2017 | Toward an Approach to Privacy Notices in IoT | Reviews a method to extract notice and choice statements from privacy policies for IoT users to decide about their privacy. |

| [78] | 2018 | Privacy issues and solutions for consumer wearables | Provides a detailed explanation about the privacy issues of consumer wearables. |

| [79] | 2018 | Internet of Things (IoT): Research, Simulators, and Testbeds | Provides a comparative analysis of IoT simulators and test beds. |

| [65] | 2018 | Polisis: Automated Analysis and Presentation of Privacy Policies Using Deep Learning | Proposes an automated framework designed to analyze privacy policies (Polisis) using deep learning. |

| [66] | 2018 | Claudette Meets GDPR: Automating the Evaluation of Privacy Policies Using Artificial Intelligence | Presents a study on automating the legal evaluation of privacy policies under GDPR using AI. |

| [13] | 2018 | Large-scale readability analysis of privacy policies | Introduces an automated toolset for extracting and analyzing the readability of nearly 50,000 privacy policies. |

| [67] | 2018 | PrivOnto: A semantic framework for the analysis of privacy policies | Presents a framework to simplify the analysis of privacy policies using crowd sourcing, machine learning, and natural language processing. |

| [68] | 2019 | Demystifying IoT security: An exhaustive survey on IoT vulnerabilities and a first empirical look on Internet-scale IoT exploitations | Reviews vulnerabilities and suggests solutions and improvements for Internet of Things. |

| [80] | 2020 | A comprehensive overview of smart wearables: The state-of-art literature, recent advances, and future challenges | Reviews the works regarding current research trends, advancements, and future challenges of wearables between 2010 and 2019. |

| [81] | 2020 | Wearables and the Internet of Things (IoT), applications, opportunities, and challenges: A Survey | Reviews the current research challenges and issues within four different sectors: health, sports, tracking, and localization and safety. |

| [69] | 2021 | Automated Extraction and Presentation of Data Practices in Privacy Policies | Presents an automated tool called PI-Extract, which is designed specifically for privacy policy analysis using neural networks to extract personal data-handling practices from the privacy policies and represent the information more concisely. |

| [82] | 2021 | Recent Advances in Wearable Sensing Technologies | Presents the recent advancements in sensor technology and in wearables. |

| [83] | 2021 | A survey on wearable technology: History, state-of-the-art and current challenges | Provides a comprehensive historical review of wearable devices. Reports on applications and some aspects of security and privacy. |

| [70] | 2021 | AI-Based Analysis of Policies and Images for Privacy-Conscious Content Sharing | Reviews techniques aimed at assisting the user in taking privacy choices using machine learning, computer vision, and natural language processing techniques. |

| [71] | 2021 | AI-Enabled Automation for Completeness Checking of Privacy Policies | Presents an AI-based method for automating the completeness check of privacy policies against GDPR requirements, achieving high precision and recall by using natural language processing and machine learning. |

| [72] | 2022 | A systematic mapping study on automated analysis of privacy policies | Reviews a systematic overview of automated privacy policy analysis, highlighting the field’s growth, research opportunities, and the need for advances in contextualizing information from privacy policies for stakeholders to provide valuable insights to end-users. |

| [73] | 2023 | Researchers’ Experiences in Analyzing Privacy Policies: Challenges and Opportunities | Highlights the complexity of analyzing companies’ privacy policies, explaining in detail the challenges faced by researchers in policy selection, retrieval, and content analysis, and suggests opportunities for methodological and structural improvements, as well as community collaboration to advance privacy policy research. |

| [27] | 2023 | Policygpt: Automated analysis of privacy policies with large language models | Uses a chatbot (PolicyGPT) based on ChatGPT and/or GPT-4 on to classify privacy policies. |

| [17] | 2023 | No More Trade-Offs. GPT and Fully Informative Privacy Policies | Proposes a chatbot based on ChatGPT 3.5 and GPT-4 to answer questions regarding privacy policies. |

| [28] | 2024 | Large Language Models: A New Approach for Privacy Policy Analysis at Scale. | Evaluates the use of ChatGPT, Llama 2, and a fine-tuned version of ChatGPT in the classification of privacy policies. |

In this work, we evaluate 4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit quantized versions of the Llama 2 [25] (which is referred to as Bloke, available from Hugging Face [84]) and base Llama 2 models. The purpose of using quantized large language models (LLMs) over regular large language models (LLMs) is motivated by the fact that the quantized LLMs do not require powerful servers (thereby decreasing energy consumption [53]) and the use of data centers at the core of the Internet. Thus, quantized LLMs can retain most of the performance of the original models without a significant loss of accuracy, which can make them a practical choice for usage in consumer devices such as consumer-level laptops/desktops and other devices.

2.3. Contributions of This Work

Our main contributions are as follows:

- We generate text of incomplete IoT privacy policies using the 4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit versions of the Bloke (a collection of quantized Llama 2 models), as well as the base Llama 2 model (zero-shot, without quantization);

- We develop prompts specifically targeting the generation of IoT privacy policy text to generate language related to privacy policies;

- We evaluate the generated texts created by the models using different quantitative metrics and check for semantic similarity.

3. Methodology

For our methodology, our goal was to require different versions of the quantized Llama 2 (Bloke) LLM and the base Llama 2 models to complete fragments of the IoT privacy policy when prompted. In this section, we describe the methodology used in the study.

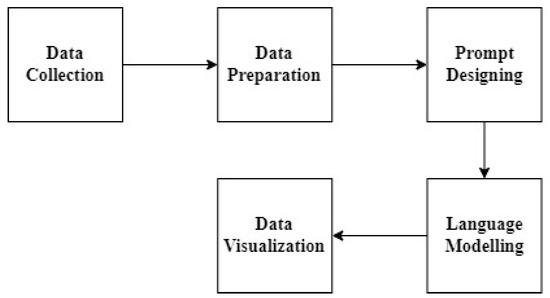

As illustrated in Figure 1, the initial stage involved data collection, where privacy policies from IoT devices were aggregated. Following this, data preparation was conducted to refine and preprocess the data, ensuring its suitability for model evaluation. The prompt-designing phase involved crafting specific prompts to guide the language model to focus on relevant aspects of privacy policies. Language modeling utilized the prepared prompts to predict or generate text mimicking the language found in IoT privacy policies. Finally, data visualization was employed during evaluation to present the models’ performances and interpret their capability in terms of modeling privacy policy text/language corpus.

Figure 1.

Workflow for evaluating quantized LLMs for IoT privacy policy analysis.

Data Collection and Preparation

For this project, we used the IoT privacy policy dataset collected by Kuznetsov et al. [85] intended for the study of the privacy policies of smart devices. The dataset includes privacy policies obtained from major IoT device manufacturers found on platforms like Amazon, Walmart, and Google Search, and encompasses a diverse array of privacy policies concerning various IoT devices, such as fitness trackers, smartwatches, smart locks, and more. A total of 626 files were extracted from this dataset containing information related to privacy policies. Each of these files contained one or more of 50 keywords related to privacy policies like “privacy policy”, “privacypolicy”, “privacy policies”, “internet of things”, “iot device”, “iot devices”, “iot”, “smart device”, “smart devices”, and “connected device”, among others.

- a.

- Prompt Design

A prompt is a set of instructions provided to an LLM in such a way that the LLM generates appropriate outputs based on a given prompt [86]. A prompt provides a clear direction to the LLM by specifying what the user is expecting in the output [86]. The quality of the output generated by the model depends on how efficiently a prompt is designed [86]. There are six building blocks of a prompt [87,88], as follows:

- Task: The task is specified in the prompt using action verbs, like analyze, summarize, write, etc. Every prompt typically begins with a verb that specifies the task. The task directs the LLM to the specific action that it is expected to perform.

- Context: Context is used to limit the possibilities of the response generated by the model. There might be situations in which the LLM generates output indefinitely, and it is crucial to limit these possibilities by considering aspects such as the user’s background, what success looks like, and the type of environment the user is in. Productive outputs from an LLM can be achieved by providing constraints to limit its outputs.

- Exemplar: Exemplar is used to include specific examples in the prompt so that the model can understand it in more detail. While an exemplar is not mandatory, adding it to a prompt will refine the quality of the output.

- Persona: Persona specifies how the users request the model to take up a role. Sometimes, the users request the model to adopt a specific role or take a certain point of view. For instance, the users may request the model to function as an online Python compiler, enabling the users to write and execute Python scripts, or to act like a Linux terminal and generate outputs based on the user commands.

- Format: Format focuses on how the output generated by the model should appear. It guides the model on organizing its response in a specific way as per the user’s requirements. For example, the user may request the model to generate the output in bullet points or in a tabular format. The format ensures that the output generated by the model is easy to read and understand.

- Tone: Tone focuses primarily on the style or emotional quality of the model’s response. The tone can be formal, informal, enthusiastic, or any other emotion that influences how the message should be conveyed.

Because the output of an LLM can vary based on the input provided, we crafted four different prompts, as shown in Table 3. These prompts were constructed using the building blocks specified above. In Table 3, for a given prompt, the task building block is highlighted in blue, the persona building block is highlighted in yellow, the context is colored as green, and finally, the tone is highlighted in gray.

Table 3.

Privacy policy assistance prompts used to generate IoT privacy policy text.

- b.

- Language Modeling

Language modeling is the process of predicting or generating text/tokens based on a previous sequence of tokens/input text. In this work, we used the base Llama 2 model and 4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit quantized versions of the Llama 2 model (zero-shot) to generate texts based on incomplete privacy policy statements/policies as inputs. We did not fine-tune these models, as our goal was to evaluate their performance after their training and quantization. We summarize the different versions of the Bloke Llama 2 LLM used in this study in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model quantization specifications and memory requirements.

- c.

- Experimental Procedure

We selected the privacy policies of 30 IoT devices (at random) from the Kuznetsov et al. [85] dataset and created an Excel sheet containing two columns—Text and Reference Text. Text was an incomplete privacy policy text statement of an IoT device (which was completed by the LLMs) and Reference Text was the complete privacy policy text of the IoT device. We used the models with the four prompts specified in Table 3 to check how changes in the prompt affected the results/outputs of the model. The outputs generated by the models were compared using semantic similarity metrics to evaluate how successful the LLMs were at modeling privacy policy language.

We created a Python script using Visual Studio Code 1.89.0. The script was then executed on a remote server with 2.0 TiB (Tebibytes) RAM, 2 AMD EPYC 7513 32-Core Processors, and 4 NVIDIA A100 GPUs, each having 80 GiB of VRAM. This server was manufactured by Supermicro (San Jose CA, USA). It worth noting that, while we used this server for the purpose of executing the experiments, each of the quantized models requires a less powerful machine to execute. Our objective was not to benchmark the requirements of the LLMs, but to evaluate their output.

There are several metrics to evaluate semantic similarity between two text corpora. We used the Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation—Longest Common Subsequence (ROUGE-Lsum) [89], Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers Precision (BERT Precision) [90], Word to Vector (Word2Vec) [91], and Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe) [92] cosine similarity to compare the semantic similarity between the text generated by the model and the reference text. Table 5 outlines the four metrics used for evaluating text generated by the quantized LLMs, along with their advantages, limitations, and applications.

Table 5.

Comparison of text evaluation metrics.

4. Results

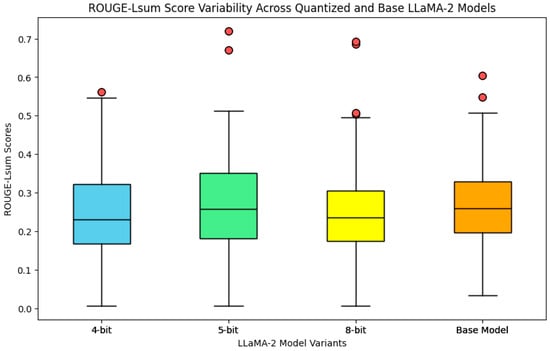

We present the results of the performance of the models for each metric using boxplots to show the distribution of the data results, and we present the median, interquartile range, and outliers of the results.

For the ROUGE-LSum metric, which assesses the n-gram overlap between the generated text and reference texts, the observed median values shown in Figure 2 were consistently below 0.3 across all prompts and models, indicating a lower level of similarity in word sequences between the generated texts and the text of the original privacy policies. Considering that scores around 0.4 are typically considered as satisfactory, the results indicate that the texts generated by the models did not replicate the original text in the policies. While the median value for the Llama 2 base model for this metric was slightly better than the ones for the quantized versions, the difference was not significant, as the interquartile boxes across all models overlapped. Also, as seen in Figure 2, there were some outliers for some privacy policy texts with scores above 0.5.

Figure 2.

Boxplots for the ROUGE-LSum metric for all prompts and across all Llama 2 models.

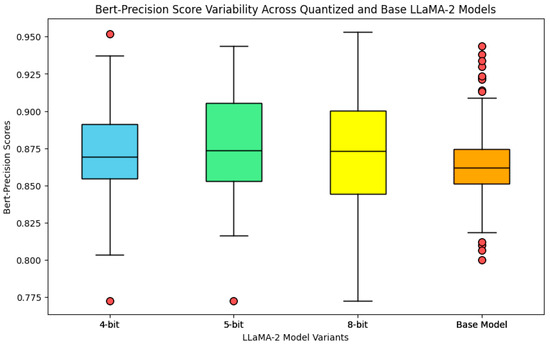

Figure 3 shows the results of the BERT Precision score metric. For this metric, we found that overall, the values for all the models (including the base model) were above 0.8, with median values around 0.87. For the BERT Precision score metric, values closer to 1 are better, showing a higher level of semantic similarity. Among the models, the base model results indicate that the base model output more consistent results (less variability) for this metric compared to the quantized versions, which exposed more variability in the data. However, there were more outliers in the base model than in the quantized ones. Figure 3 also shows that there were no significant differences among the models.

Figure 3.

Boxplots for the BERT precision score metrics for all prompts and across all Llama 2 models.

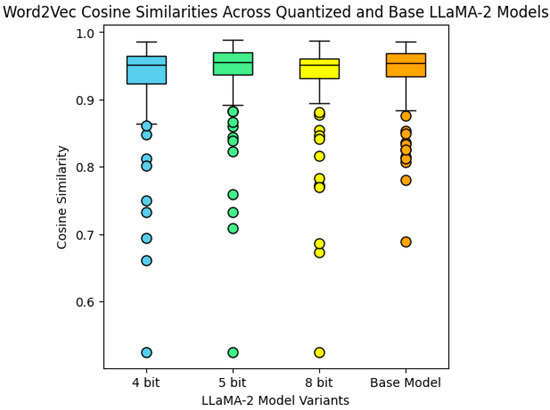

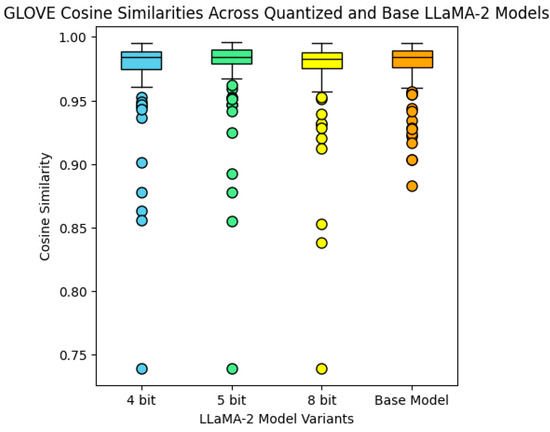

The results of the Word2Vec cosine similarity metric (Figure 4) show that the outputs of all the models had similar scores, with median values above 0.95. The boxplots also showed similar distributions among all models, especially for the 5-bit, 8-bit, and full models, and there was more variation on the 4-bit model. For this metric, values closer to 1 indicate better semantic similarity. For the GloVe cosine similarity (Figure 5), the models showed similar performances. It worth noting that all the models had outliers with lower scores for both metrics, indicating that the text generated for these policies had less similarity to the original text.

Figure 4.

Boxplots for the Word2Vec cosine similarity metric for all prompts and across all Llama 2 models.

Figure 5.

Boxplots for the GLOVE cosine similarity metric for all prompts and across all Llama 2 models.

Overall, our results show that the quantized models had similar performances to the base Llama 2 base model. While the models did not replicate the exact sequence of words from the original documents, they were still able to generate text with a high degree of semantic similarity. Thus, quantized Llama 2 models can generate coherent and contextual texts comparable to the ones generated by the base Llama 2 model and comparable to the language used in the original privacy policies.

Limitations

We highlight the following limitations of our study:

- Model behavior on specific policy types: Our analysis did not differentiate the models’ performance with varying types of privacy policy statements (e.g., statements specifically related to data collection or statements pertaining to third-party data sharing). This limitation restricts the granularity of our insights into how well quantized models handle different thematic elements within privacy policies. Subsequent research could focus on this aspect by categorizing privacy policy statements into themes and evaluating the models’ performance across these categories.

- Fine-tuning of quantized models: The study excluded the exploration of fine-tuning of the quantized models for specific types of privacy policy texts. Fine-tuning could potentially enhance the models’ accuracy and applicability to real-world scenarios, making them more effective at generating privacy policy texts that are relevant to users’ comprehension and decision making. Investigating the effects of fine-tuning on quantized models could reveal significant improvements in performance and utility.

- Impact on policy comprehension: We did not evaluate the perception of the generated privacy policy texts from the human perspective. It would be beneficial for future studies to include user studies and/or surveys to evaluate texts generated by trained personnel.

5. Conclusions

We evaluated the performance of the base and quantized (4-bit, 5-bit, and 8-bit) versions of the Llama 2 LLM in the context of generating privacy policy text using four different prompts and incomplete IoT privacy policy texts as inputs to the LLMs. To assess the quality of the generated texts against the original policies, we employed a suite of metrics, including ROUGE-Lsum, BERT precision, and Word2Vec and GloVe cosine similarities. These metrics provided a comprehensive evaluation of the generated texts, from measuring n-gram overlap to assessing semantic coherence/similarity.

We observed that quantized models can generate texts similar to the texts generated by the base Llama 2 model, which are also coherent and comparable to the language used in IoT privacy policies crafted by legal teams. Our results suggest that quantized Llama 2 models can be used in applications related to the generation and analysis of IoT privacy policies in consumer-grade computer/devices without a substantial compromise in performance, aligning with the ongoing efforts to make AI more accessible and efficient. Future work can address the performance of fine-tuned quantized models trained with IoT privacy policy texts; it can also explore the effects of different quantization techniques, like quantization-aware training, human evaluation of outputs, and the performance of newer LLM models developed to execute in consumer-level devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.P.; methodology, B.M. and A.J.P.; software, B.M.; investigation, B.M. and A.J.P.; resources, B.M. and A.J.P.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M. and A.J.P.; writing—review and editing, A.J.P.; visualization, B.M.; supervision, A.J.P.; funding acquisition, B.M and A.J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of Nebraska at Omaha Graduate Research and Creative Activity (GRACA) Award.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study and the scripts used can be found at https://github.com/bhavanimalisetty/Evaluating-Quantized-LLaMA-Model-for-IoT-Privacy-Policy-Language/ accessed on 26 May 2024.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which helped improve the paper’s content, quality, and organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, N.; Shamkuwar, M.; Singh, I. The History, Present and Future with IoT. Internet of Things and Big Data Analytics for Smart Generation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Khan, S.U.; Zaheer, R.; Khan, S. Future internet: The internet of things architecture, possible applications and key challenges. In Proceedings of the 2012 10th International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, 17–19 December 2012; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulmalek, S.; Nasir, A.; Jabbar, W.A.; Almuhaya, M.A.; Bairagi, A.K.; Khan, M.A.M.; Kee, S.H. IoT-based healthcare-monitoring system towards improving quality of life: A review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Tomar, R.; Choudhury, T.; Perumal, T.; Mahdi, H.F. Data Driven Approach Towards Disruptive Technologies. In Proceedings of MIDAS 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Del Rio, D.D.F. Smart home technologies in Europe: A critical review of concepts, benefits, risks and policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, F.; Calore, M.; Zucchetto, D.; Polese, M.; Zanella, A. IoT: Internet of threats? A survey of practical security vulnerabilities in real IoT devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8182–8201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.J.; Zeadally, S.; Jabeur, N. Investigating security for ubiquitous sensor networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 109, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauti, S.; Laato, S.; Pitkämäki, T. Man-in-the-browser attacks against IoT devices: A study of smart homes. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soft Computing and Pattern Recognition (SoCPaR 2020), Online, 15–18 December 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 12, pp. 727–737. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, E.; Aidoo, A.; Fuhrer, J.; Stahl, J.; Ziörjen, M.; Stiller, B. Landscape of IoT security. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2022, 44, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, K.; Park, Y.; Ahn, J.H. Willingness to provide personal information: Perspective of privacy calculus in IoT services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.J.; Zeadally, S.; Cochran, J. A review and an empirical analysis of privacy policy and notices for consumer Internet of things. Secur. Priv. 2018, 1, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, N. “I agree to the terms and conditions”: (How) do users read privacy policies online? An eye-tracking experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, B.; Ermakova, T.; Lentz, T. Large-scale readability analysis of privacy policies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Intelligence 2017, Leipzig, Germany, 23–26 August 2017; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, S.; Zeadally, S. Privacy policy analysis of popular web platforms. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2016, 35, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Das, S.; Dewri, R. Evolution of Composition, Readability, and Structure of Privacy Policies over Two Decades. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2023, 3, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, T.; Rauti, S.; Carlsson, R. An assessment of privacy policies for smart home devices. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies, Ruse, Bulgaria, 16–17 June 2023; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pałka, P.; Lippi, M.; Lagioia, F.; Liepiņa, R.; Sartor, G. No More Trade-Offs. GPT and Fully Informative Privacy Policies. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2402.00013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, M. Talking about large language models. Commun. ACM 2024, 67, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. Galactica: A large language model for science. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09085. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Lin, J.; Seznec, M.; Wu, H.; Demouth, J.; Han, S. Smoothquant: Accurate and efficient post-training quantization for large language models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 38087–38099. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, D.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; et al. Policygpt: Automated analysis of privacy policies with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.10238. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, D.; Yang, I.; Del Alamo, J.M.; Sadeh, N. Large Language Models: A New Approach for Privacy Policy Analysis at Scale. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.20900. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Recurrent convolutional neural networks for text classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, TX, USA, 25–30 January 2015; Volume 29, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Byun, S.; Jung, K. Multimodal speech emotion recognition using audio and text. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Karpathy, A.; Toderici, G.; Shetty, S.; Leung, T.; Sukthankar, R.; Fei-Fei, L. Large-scale video classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1725–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Ren, J.S.; Liu, C.; Jia, J. Deep convolutional neural network for image deconvolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 1790–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W.; Kann, K.; Yu, M.; Schütze, H. Comparative study of CNN and RNN for natural language processing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01923. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, F.; Lv, J.; Duan, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, G.; Tian, G. Do RNN and LSTM have long memory? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 11365–11375. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://cohere.com/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, S.; Ding, S.; Pang, C.; Shang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Ernie 3.0: Large-scale knowledge enhanced pre-training for language understanding and generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.02137. [Google Scholar]

- Almazrouei, E.; Alobeidli, H.; Alshamsi, A.; Cappelli, A.; Cojocaru, R.; Debbah, M.; Goffinet, E.; Heslow, D.; Launay, J.; Malartic, Q.; et al. Falcon-40B: An open large language model with state-of-the-art performance. Find. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. ACL 2023, 2023, 10755–10773. [Google Scholar]

- Thoppilan, R.; De Freitas, D.; Hall, J.; Shazeer, N.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Cheng, H.T.; Jin, A.; Bos, T.; Baker, L.; Du, Y.; et al. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.08239. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar]

- Bellagente, M.; Tow, J.; Mahan, D.; Phung, D.; Zhuravinskyi, M.; Adithyan, R.; Baicoianu, J.; Brooks, B.; Cooper, N.; Datta, A.; et al. Stable LM 2 1.6 B Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.17834. [Google Scholar]

- Anil, R.; Dai, A.M.; Firat, O.; Johnson, M.; Lepikhin, D.; Passos, A.; Shakeri, S.; Taropa, E.; Bailey, P.; Chen, Z.; et al. Palm 2 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10403. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.; Tang, O.Y.; Connolly, I.D.; Fridley, J.S.; Shin, J.H.; Sullivan, P.L.Z.; Cielo, D.; Oyelese, A.A.; Doberstein, C.E.; Telfeian, A.E.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT, GPT-4, and Google Bard on a neurosurgery oral boards preparation question bank. Neurosurgery 2022, 10, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 5485–5551. [Google Scholar]

- Le Scao, T.; Fan, A.; Akiki, C.; Pavlick, E.; Ilić, S.; Hesslow, D.; Castagné, R.; Luccioni, A.S.; Yvon, F.; Gallé, M.; et al. Bloom: A 176b-parameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.05100. [Google Scholar]

- Biderman, S.; Schoelkopf, H.; Anthony, Q.G.; Bradley, H.; O’Brien, K.; Hallahan, E.; Khan, M.A.; Purohit, S.; Prashanth, U.S.; Raff, E.; et al. Pythia: A suite for analyzing large language models across training and scaling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 2397–2430. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, J.W.; Borgeaud, S.; Cai, T.; Millican, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Song, F.; Aslanides, J.; Henderson, S.; Ring, R.; Young, S.; et al. Scaling language models: Methods, analysis & insights from training gopher. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.11446. [Google Scholar]

- Soltan, S.; Ananthakrishnan, S.; FitzGerald, J.; Gupta, R.; Hamza, W.; Khan, H.; Peris, C.; Rawls, S.; Rosenbaum, A.; Rumshisky, A.; et al. Alexatm 20b: Few-shot learning using a large-scale multilingual seq2seq model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.01448. [Google Scholar]

- Du, N.; Huang, Y.; Dai, A.M.; Tong, S.; Lepikhin, D.; Xu, Y.; Krikun, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, A.W.; Firat, O.; et al. Glam: Efficient scaling of language models with mixture-of-experts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 5547–5569. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.D.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar]

- van Baalen, M.; Kuzmin, A.; Nagel, M.; Couperus, P.; Bastoul, C.; Mahurin, E.; Blankevoort, T.; Whatmough, P. GPTVQ: The Blessing of Dimensionality for LLM Quantization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15319. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Magno, M.; Qi, X. BiLLM: Pushing the Limit of Post-Training Quantization for LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04291. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Han, K.; Zhang, W.; Ma, S.; Gao, W. Post-training quantization for vision transformer. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 28092–28103. [Google Scholar]

- Banner, R.; Nahshan, Y.; Soudry, D. Post training 4-bit quantization of convolutional networks for rapid-deployment. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Nahshan, Y.; Chmiel, B.; Baskin, C.; Zheltonozhskii, E.; Banner, R.; Bronstein, A.M.; Mendelson, A. Loss aware post-training quantization. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 3245–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubara, I.; Nahshan, Y.; Hanani, Y.; Banner, R.; Soudry, D. Accurate post training quantization with small calibration sets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 4466–4475. [Google Scholar]

- Hubara, I.; Nahshan, Y.; Hanani, Y.; Banner, R.; Soudry, D. Improving post training neural quantization: Layer-wise calibration and integer programming. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10518. [Google Scholar]

- Sehrawat, D.; Gill, N.S. Smart sensors: Analysis of different types of IoT sensors. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 23–25 April 2019; pp. 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh, N.; Acquisti, A.; Breaux, T.D.; Cranor, L.F.; McDonald, A.M.; Reidenberg, J.R.; Smith, N.A.; Liu, F.; Russell, N.C.; Schaub, F.; et al. The usable privacy policy project. In Technical Report, CMU-ISR-13-119; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atzori, L.; Iera, A.; Morabito, G. The internet of things: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 2787–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmeck, S.; Bellovin, S.M. Privee: An architecture for automatically analyzing web privacy policies. In Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 14), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–22 August 2014; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.; Schaub, F.; Dara, A.A.; Liu, F.; Cherivirala, S.; Leon, P.G.; Andersen, M.S.; Zimmeck, S.; Sathyendra, K.M.; Russell, N.C.; et al. The creation and analysis of a website privacy policy corpus. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; Volume 1, pp. 1330–1340.

- Shayegh, P.; Ghanavati, S. Toward an approach to privacy notices in IoT. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 25th International Requirements Engineering Conference Workshops (REW), Lisbon, Portugal, 4–8 September 2017; pp. 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Harkous, H.; Fawaz, K.; Lebret, R.; Schaub, F.; Shin, K.G.; Aberer, K. Polisis: Automated analysis and presentation of privacy policies using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 531–548. [Google Scholar]

- Contissa, G.; Docter, K.; Lagioia, F.; Lippi, M.; Micklitz, H.W.; Pałka, P.; Sartor, G.; Torroni, P. Claudette Meets GDPR: Automating the Evaluation of Privacy Policies Using Artificial Intelligence; SSRN Scholarly; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oltramari, A.; Piraviperumal, D.; Schaub, F.; Wilson, S.; Cherivirala, S.; Norton, T.B.; Russell, N.C.; Story, P.; Reidenberg, J.; Sadeh, N. PrivOnto: A semantic framework for the analysis of privacy policies. Semant. Web 2018, 9, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshenko, N.; Bou-Harb, E.; Crichigno, J.; Kaddoum, G.; Ghani, N. Demystifying IoT security: An exhaustive survey on IoT vulnerabilities and a first empirical look on Internet-scale IoT exploitations. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2702–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.; Shin, K.G.; Choi, J.M.; Shin, J. Automated Extraction and Presentation of Data Practices in Privacy Policies. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2021, 2021, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, F.; Demontis, A.; Dessì, S.; Muscas, M.; Riboni, D. AI-Based Analysis of Policies and Images for Privacy-Conscious Content Sharing. Future Internet 2021, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, O.; Abualhaija, S.; Torre, D.; Sabetzadeh, M.; Briand, L.C. AI-enabled automation for completeness checking of privacy policies. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 4647–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Alamo, J.M.; Guaman, D.S.; García, B.; Diez, A. A systematic mapping study on automated analysis of privacy policies. Computing 2022, 104, 2053–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaidli, A.; Fidan, S.; Doan, A.; Herakovic, G.; Srinath, M.; Matheson, L.; Wilson, S.; Schaub, F. Researchers’ experiences in analyzing privacy policies: Challenges and opportunities. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2023, 4, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jayaraman, S. Wearables: Fundamentals, advancements, and a roadmap for the future. In Wearable Sensors; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Aledhari, M.; Ayyash, M. Internet of things: A survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 2347–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.; Hu, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Lan, G.; Khalifa, S.; Thilakarathna, K.; Hassan, M.; Seneviratne, A. A survey of wearable devices and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 2573–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Bae, M.; Kim, H. Future of IoT networks: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.J.; Zeadally, S. Privacy issues and solutions for consumer wearables. It Prof. 2017, 20, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshev, M.; Baig, Z.; Bello, O.; Zeadally, S. Internet of things (iot): Research, simulators, and testbeds. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 5, 1637–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknejad, N.; Ismail, W.B.; Mardani, A.; Liao, H.; Ghani, I. A comprehensive overview of smart wearables: The state of the art literature, recent advances, and future challenges. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dian, F.J.; Vahidnia, R.; Rahmati, A. Wearables and the Internet of Things (IoT), applications, opportunities, and challenges: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 69200–69211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.J.; Zeadally, S. Recent advances in wearable sensing technologies. Sensors 2021, 21, 6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometov, A.; Shubina, V.; Klus, L.; Skibińska, J.; Saafi, S.; Pascacio, P.; Flueratoru, L.; Gaibor, D.Q.; Chukhno, N.; Chukhno, O.; et al. A survey on wearable technology: History, state-of-the-art and current challenges. Comput. Netw. 2021, 193, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bloke Llama 2 LLM Model. Available online: https://huggingface.co/TheBloke/Llama-2-7B-GGML (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Kuznetsov, M.; Novikova, E.; Kotenko, I.; Doynikova, E. Privacy policies of IoT devices: Collection and analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11382. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.simplebizsupport.com/ai-six-building-blocks-successful-prompt/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Available online: https://www.insidr.ai/advanced-guide-to-prompt-engineering/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Proceedings of the Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09675. [Google Scholar]

- Church, K.W. Word2Vec. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2017, 23, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).