Abstract

Cyber sextortion attacks are security and privacy threats delivered to victims online, to distribute sexual material in order to force the victim to act against their will. This continues to be an under-addressed concern in society. This study investigated social engineering and phishing email design and influence techniques in susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks. Using a quantitative methodology, a survey measured susceptibility to cyber sextortion with a focus on four different email design cues. One-way repeated measures ANOVA, post hoc comparison tests, Friedman nonparametric test, and Spearman correlation tests were conducted with results indicating that attention to email source and title/subject line significantly increased individuals’ susceptibility, while attention to grammar and spelling, and urgency cues, had lesser influence. As such, the influence of these message-related factors should be considered when implementing effective security controls to mitigate the risks and vulnerabilities to cyber sextortion attacks.

1. Introduction

Sextortion, an act of threatening to expose sexually explicit material in order to get individuals to perform an act against their will, such as sexual acts, share sexually explicit material, or in the most common cases for the purpose of obtaining money [1], continues to be an under-addressed issue in society. While other similar terms such as sexting, nonconsensual pornography, and revenge pornography are all related to sextortion by the illegal or malicious distribution of sexual material, sextortion is distinguished from these terms by the threat to distribute sexual material in order to force someone to do something, even if the threat is never carried out. Sextortion cases generally fall into two broad groups: either an outcome of a sexual relationship in which an aggrieved partner tries to force reconciliation or humiliate the victim, or a result of the victim having met the perpetrator online [2]. The nature of threats to distribute sexual material generally include posting images online, sending images to acquaintances or family members, including the victim’s identity with the posted material, getting victims in trouble at work or school or with the law, stalking or physically hurting victims or their families, and more [2]. Consequences of sextortion threats for victims generally include the loss of a relationship; seeing a health practitioner; moving house; having a school or job-related problem; incurring financial costs; and suffering from fear, shame, and embarrassment [2].

The current study will specifically investigate cyber sextortion scams, as opposed to other forms of sextortion including sextortion threats that occur as a result of a relationship between victim and perpetrator whether face-to-face or online. Cyber sextortion has been shown to account for approximately 40% of all sextortion cases [2]. Cyber sextortion scams have been defined in the current study as a threat, delivered to victims through online communication mediums including email, to distribute sexual material in order to force the victim to do something. The victim is usually encouraged to pay money to the perpetrator. As the sextortion threat is a scam, the perpetrator will usually be unable to execute the threat regardless of whether the victim has been successfully coerced.

Studies show that sextortion, particularly cyber sextortion, is on the rise [3], and affects thousands to millions of people [4]. However, sextortion attacks and individual susceptibility to these attacks are dramatically understudied [5]. As such, little is known about the characteristics of people who are most likely to be vulnerable to sextortion attacks, as well as which aspects of sextortion attacks are likely to be persuasive in encouraging victims to cooperate with the perpetrator’s demands. Similarly, little is known about how these attacks can best be mitigated.

As the sextortion attacks are mostly generated from an acquaintance of the victims, the goal of this study includes the following:

- To present a comprehensive understanding of the individuals who carry out sextortion attacks to coerce their victims into parting with money, sex, additional images, or a resumption of the relationship.

- To examine the role that various design cues, including anxiety, arousal, reticence, and reduced spontaneity, play in deception and persuasion as well as how they affect a person’s susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks.

- To identify the traits of the person who was used to make the email more pertinent, to show how the recipient interprets emails, and to recognize the main sorts of messages that catch their attention.

- Finally, a survey-based, non-experimental methodology was employed to determine participants’ sensitivity to cyber sextortion attacks using predictor variables (design cues related to cyber sextortion) and outcome variables.

This paper begins by providing a theoretical background on the theories of susceptibility to deception, persuasion, and cyber sextortion. Firstly, a form of social engineering called phishing is researched and discussed to aid in in-depth investigation and understanding of cyber sextortion. Secondly, both social engineering techniques, phishing and cyber sextortion involve a level of deception, coercion, and persuasion/manipulation of victims. Hence, a number of theories related to deception and persuasion are also discussed. Thirdly, the main theory of the Integrated Information Processing Model of Phishing Susceptibility [6] is examined within the context of design cues and individual habits in regard to susceptibility to cyber sextortion. The study then outlines the aims and hypotheses, methodology for quantitative survey data collection and analysis, followed by results, discussions, and recommendations.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Phishing Attacks and Sextortion

One of the main channels by which cyber sextortion takes place is through online applications, such as social media and email. While current knowledge related to cyber sextortion is limited, a similar form of social engineering (deception online), called phishing, is much more well-known [6,7,8]. Phishing was used as a theoretical basis for the current study due to its similarity with cyber sextortion scams. Phishing is defined as “a scalable act of deception whereby impersonation is used to obtain information from a target” [9]. Phishing can occur through a number of communication mediums, including the Internet, Short Messaging Service (SMS), and telephone. When communicating through the Internet, a number of platforms may be used including email, e-fax, instant messaging, websites, and Wi-Fi [10]. Similarly, a number of technical approaches may be used that capitalize on the vulnerabilities of the victim’s computer, including the use of malicious software downloaded via an email attachment or a man-in-the-middle attack whereby the perpetrator “listens” to a communication as it is in transit from source to destination [10,11].

Phishing has a number of similarities with cyber sextortion scams that make it useful as a theoretical basis for the investigation of sextortion. Firstly, both phishing and sextortion are social engineering techniques that attempt to coerce a victim into doing something. In the case of phishing, this usually involves divulging sensitive information, while in the case of sextortion, this can involve divulging sensitive information, paying money, and more [11]. Secondly, both attempt to deceive the victim. In the case of phishing, the perpetrator may pretend to be a legitimate business organization asking for the victim’s credentials, or the perpetrator may try to coerce the victim into believing that the victim is in trouble and the only solution is to adhere to the perpetrator’s demands. In the case of cyber sextortion scams, the deception is that the perpetrator actually has sexual material pertaining to the victim and that they will distribute it. Thirdly, both often occur online, such as via email [11].

A number of factors have been shown to influence people’s susceptibility to phishing attempts. By far, the majority of factors studied have focused on personality, demographic, or behavioral variables. For example, computer self-efficacy, security awareness, suspicion, conscientiousness, and cognitive effort have been shown to be associated with less susceptibility [12]. Similarly, habitual email and social media use, impulsivity, and the Big Five personality traits of openness, extraversion, and agreeableness have been shown to be associated with greater susceptibility [13]. Although studied less, another factor that influences people’s susceptibility is the techniques and design features of the phishing messages themselves. For example, creating a sense of loss or urgency to respond and offering rewards have been shown to increase susceptibility [14]. Similarly, phishing messages that are designed to appear as though they have come from an authority figure are known to increase susceptibility, such as through the use of reputable brand names and logos [15].

2.2. Social Engineering Theories of Deception and Persuasion

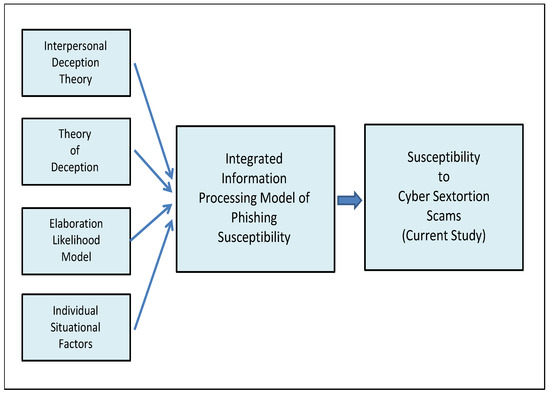

Social engineering techniques that involve cyber sextortion (and phishing) utilize strong elements of both deception and persuasion [16]. The perpetrator of a cyber sextortion scam, for example, will both attempt to deceive their victims into believing that they are in possession of sexually explicit material involving their victims when they are not in possession of such material, and simultaneously attempt to persuade their victims into doing something such as provide them with monetary rewards in exchange for not distributing the sexual material to the public or to friends and family. As such, a number of theories of deception and persuasion have informed the academic literature on phishing susceptibility and thus the current study on cyber sextortion scams. A diagram showing how each of the theories and models relates to the current study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Each of the theories and models of deception, persuasion, and phishing susceptibility; and their relation to the current study.

Firstly, Interpersonal Deception Theory argues that identifying deception involves detecting the subtle spoken and non-spoken cues that deceivers display during the process of deception [17]. For example, non-spoken cues identified in the theory that are often over-exaggerated by deceivers include an over-controlled or rigid presentation, inexpressiveness, and reduced spontaneity. Other cues identified may include nervousness, arousal, negative affect, hesitation, uncertainty, and incompleteness, vagueness, and indirectness of the deceiver’s message. As the deception involved in cyber sextortion scams (and phishing) occurs entirely online (such as via email) without any interpersonal interaction, the cues involved in deception detection will involve the content and layout of the online message.

Secondly, the Theory of Detection focuses more specifically on the receiver’s interpretation of the sender’s message during the process of identifying deception [18]. The theory argues that identifying deception involves discovering the inconsistencies between the sender’s message and the receiver’s prior expectations and knowledge. The process of identifying deception consists of four stages where the sender (a) pays attention to elements of the deceiver’s message and detects discrepancies, (b) uses prior knowledge and experience to create an explanation of the discrepancies, (c) compares the explanation of the discrepancies against some criteria, and (d) finally forms an assessment of the deceptiveness of the message. The relevance of this theory for the current study is that it shows that the mere existence of deception cues is not enough for identifying deceptions. Identifying deception also involves the receiver paying attention to, and interpreting, these deception cues.

Two extra theories of persuasion that have informed the academic literature on phishing susceptibility include the Elaboration Likelihood Model [19], as well as various O-S-I-R models of decision-making [20]. ELM is a theory of information processing that attempts to explain the persuasive influence of advertising messages by suggesting that consumers cognitively process messages via two routes: a central route and a peripheral route. The central route involves a careful examination and assessment of information based on its validity, pros, and cons. The peripheral route sacrifices the cognitive effort involved in a careful assessment of the message in favor of focusing on simple cues in the message that are most salient to the consumer and is thus more susceptible to persuasion. In the context of phishing susceptibility, prior research has shown that phishing scams which are more persuasive are more likely to be peripherally processed [20]. O-S-I-R models of individual decision-making extend these previous theories of deception and persuasion by suggesting that a stimulus (S) that leads to a response (R) and is mediated by the individual’s interpretation of the stimulus (I) is also influenced by other contextual variables, such as the individual’s personality traits, motivations, and other characteristics (O), that ultimately affect their interpretation of the stimulus and their response to it. For example, much research has shown that the personality characteristics of the Big Five personality traits—as well as other individual characteristics such as impulsivity, computer self-efficacy, and habitual email and social media use—influence individual susceptibility to phishing scams [21].

2.3. Integrated Information Processing Model of Phishing and Sextortion Susceptibility

While the above theories on deception and persuasion were created to explain social and interpersonal phenomena in general, they have also aided in our current understanding of the factors involved in individual susceptibility to phishing attacks by providing a theoretical premise for a model of phishing susceptibility called the Integrated Information Processing Model of Phishing [21]. The model suggests that a number of factors work either alone or in combination to influence the likelihood that a victim will respond and hence be susceptible to a phishing email. Firstly, the model proposes that individuals who attend to specific design cues within the email (email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line) will be differentially affected in their likelihood of responding to the email. This occurs both directly and indirectly through a cognitive elaboration process involving hypothesis assessment and a comparison with prior knowledge. Secondly, the model proposes that certain characteristics of the individual will influence the level of attention they pay to the email, the level of cognitive elaboration they exert on the email, and/or the likelihood that they will respond to the email. These characteristics include the perceived relevance of the email, the volume of other emails the individual receives on a given day, the individual’s level of knowledge regarding online deception and phishing attacks, and the individual’s level of computer self-efficacy.

Of the specific design cues within phishing emails identified in the IIPM as affecting susceptibility to phishing attacks, email source refers to either the name or address that appears in the sender line of the email. According to the IIPM, information about the source of an email has the potential of revealing its level of authenticity. Thus, individuals who attend to this information within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to assess the email as inauthentic, reducing the likelihood of responding to it. Research on phishing has revealed that participants are indeed more likely to judge a phishing email as illegitimate or suspicious based on the content within the sender line [22].

Within the IIPM, spelling and grammar cues refer to the amount of both spelling and grammatical errors that appear within the phishing email. Similar to email source, the amount of spelling and grammatical errors has the potential of revealing the email’s level of authenticity. Thus, individuals who attend to the spelling and grammar within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to assess the email as inauthentic, reducing the likelihood of responding to it. Research on phishing has shown that participants are more likely to judge an email as illegitimate or dismiss the email outright due to spelling and language errors and an untidy layout.

Within the IIPM, the title/subject line refers to the title or subject of the phishing email. Unlike email source and spelling/grammar, the title or subject is used in phishing emails as a social engineering technique for attracting the recipient’s attention and cuing them to the relevance of the email in an attempt to elicit a response. As the title or subject is used to create compliance, the IIPM predicts that individuals who attend to the title or subject of the email within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to respond to them, increasing susceptibility.

Within the IIPM, urgency cues refer to elements of a phishing email that attempt to elicit emotions of fear, threat, or loss, enticing the recipient to respond promptly without evaluating the legitimacy of the email. Examples of urgency cues within the phishing context may include the threat of suspension or deletion of the recipient’s accounts, or the need to accept a timely offer before it expires [23]. According to the IIPM, urgency cues monopolize a recipient’s cognitive capacity, preventing an effective evaluation of the legitimacy of the email. As a result, more automatic forms of cognition are used, which are more susceptible to persuasive influence [24]. As urgency cues are used to create compliance, the IIPM predicts that individuals who attend to urgency cues within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to respond to them, increasing susceptibility to cyber sextortion.

2.4. Hypothesis Development

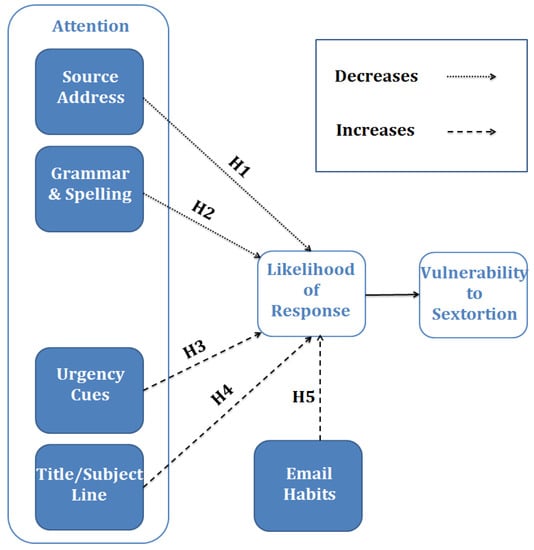

Existing knowledge of phishing attacks allows the prediction of design features of phishing emails and which personality characteristics of the victims who receive them influence victims’ likelihood of responding to these emails and hence become susceptible to phishing attacks. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for cyber sextortion attacks. Due to the fact that sextortion attacks have been dramatically understudied, little is known about what influences victims’ susceptibility to them. Using the email cues identified in the IIPM as influencing susceptibility to phishing attacks (email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line) psychological and cybersecurity theories and techniques to investigate this phenomenon are applied to pave the way for future research and an understanding for how these attacks can be effectively mitigated. The aim of this study is to extend our understanding of cyber sextortion by using our current knowledge of the research literature surrounding social engineering attack-based techniques such as phishing to investigate the effects of message-related factors on cyber security behavior and susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks. Hence, the following hypotheses will be tested. A diagram of the study’s hypotheses is presented in Figure 2, showing how paying attention to each design cue within sextortion emails is expected to influence the likelihood of responding to these emails, and hence of influencing susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks.

Figure 2.

The hypothesized relationship between the attention given to various design cues within sextortion emails; and their effects on participants’ likelihood of responding to these emails, and hence being vulnerable to sextortion attacks.

Hypothesis one: Research has shown that people who focus attention on the email source of phishing emails are more likely to assess the email as inauthentic, reducing the likelihood of responding to it [25]. Therefore, hypothesis one is that focusing attention on the email source (reply-to address) in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as less likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on the email source (reply-to address).

Hypothesis two: Research has shown that individuals who attend to the spelling and grammar within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to assess the email as inauthentic, reducing the likelihood of responding to it [26]. Therefore, hypothesis two is that focusing attention on grammar and spelling in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as less likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on grammar and spelling.

Hypothesis three: Research has shown that individuals who attend to the title or subject of the email within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to respond to it, increasing susceptibility [26]. Therefore, hypothesis three is that focusing attention on the title/subject line in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as more likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on the title/subject line.

Hypothesis four: Research has shown that individuals who attend to urgency cues within the context of phishing attacks are more likely to respond to them, increasing susceptibility [26]. Therefore, hypothesis four is that focusing attention on urgency cues in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as more likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on urgency cues.

Hypothesis five: Poor email and security habits have been shown to increase individuals’ vulnerability to cyber-attacks [26]. Therefore, hypothesis five is focused on participants’ general email habits, security email habits, and attentional email habits correlating with their level of susceptibility to each of the email design cues.

The null hypotheses of all the above-hypothesized statements (H1 to H5) are also vital in the sense that they will still indicate some level of susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks in the event that H1 to H5 are non-significant. The methodology by which these hypotheses on cyber sextortion are explored is discussed in the next section.

3. Methods

A survey-based, non-experimental (correlational) design was used with predictor variables and outcome variables. The predictor included the specific design cues within cyber sextortion emails on which participants were instructed to focus their attention (email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line), which previous research has identified as influencing susceptibility to social engineering attacks such as phishing. Control conditions were also included as another level of predictor variables where participants’ focus of attention was not specified. The outcome variables included participants’ level of susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks measured on a self-report scale of how likely participants were to respond to each cyber sextortion email that they were shown.

3.1. Participants

Eighty-seven participants chose to take part in the study. One participant was excluded from the study as they chose not to consent to participate and thus did not complete the survey, resulting in a final sample size of 86. In total, 19 participants were male, 66 were female, and 1 chose the gender category of ‘other’. In total, 31 participants were under the age of 20 years, 36 participants were between the ages of 20 and 29 years, 10 participants were between the ages of 30 and 39 years, 6 participants were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, and 3 participants were between the ages of 50 and 59 years. Other demographic characteristics that were collected from participants (see Table 1) included whether they have had any: (a) cybersecurity education or training, (b) experiences with phishing or scam emails, (c) experiences with cyber sextortion scams, or (d) experiences with any other form of cyberbullying or harassment.

Table 1.

Participant responses to demographic questions.

3.2. Measures

One extended questionnaire consisting of 49 questions was used in the study. It was composed of three parts. The first part consisted of an adapted version of the Self-Report Habit Index (SRHI) [27]. The second and third parts consisted of the Sextortion Susceptibility Survey (SSS).

3.2.1. Self-Report Habit Index

The SRHI is a self-report questionnaire that measures respondents’ automatic and habitual behavior in a given context [27]. It was created to be adaptable as a measure of any habitual behavior of interest. For the current study, the SRHI was adapted and modified to measure respondents’ email habits. Previous research has shown that email habits influence susceptibility to phishing attacks. As it is possible that email habits also influence susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks, this modified version of the SRHI was used to gather foundational information that might help account for possible discrepancies in measuring the effect of attention to specific design cues within cyber sextortion emails on participants’ likelihood of responding to them.

The modified version of the SRHI consisted of 23 statements and an instruction for respondents to indicate on a 4-point Likert scale how much they agree with each statement. Statements ranged from general topics about respondents’ email habits (e.g., “I check my emails frequently” and “I check my emails without having to consciously remind myself to do it”) to statements about respondents’ email security habits (e.g., “I use strong passwords for my email account”) and respondents’ email habits regarding each of the four email design cues of interest to the current study (e.g., “I usually respond to emails without paying specific attention to the sender name and address”). Respondents’ answers were coded as: 1 = Very Unlikely, 2 = Unlikely, 3 = Likely, and 4 = Very Likely.

3.2.2. Sextortion Susceptibility Survey

The SSS is a self-report questionnaire generated by the researchers based on a database of previous cyber sextortion attacks via email perpetrated by cyber criminals. This was used in the current study to investigate the effect of paying attention to specific design cues within cyber sextortion emails on participants’ likelihood of responding to cyber sextortion emails, and hence being susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks. The specific design cues measured in the SSS included email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line—design cues that had been previously identified as influencing susceptibility to social engineering attacks such as phishing emails.

The SSS consisted of 20 questions divided into two parts. The first part consisted of eight identical questions, with each question asking the respondent how likely they were to respond to the accompanying email. Accompanying each question was an example of a cyber sextortion email, and a 4-point Likert scale on which respondents could record their response to each question (1 = Very Unlikely, 2 = Unlikely, 3 = Likely, and 4 = Very Likely). All examples of cyber sextortion emails were predesigned by the researchers, although the content of the emails was based on real cyber sextortion emails employed by cyber criminals. This approach to using real cyber sextortion emails is in line with previous research on phishing (e.g., Williams & Polage, 2019) where real phishing emails were used to measure participants’ level of susceptibility. Other than the content of the email, the information in the sender line, and the information in the title/subject line, all emails were kept identical in color and layout to avoid adding any confounding variables. Respondents were not asked to pay attention to any specific design cues within the cyber sextortion emails in the first part of the SSS. This was done deliberately so as not to prime respondents to the design cues on which they would later be instructed to focus their attention in the second part of the SSS. By not specifying where respondents should focus their attention, a measure could be made of how likely they were to respond to cyber sextortion emails irrespective of where in the emails they focused their attention.

The second part consisted of 12 questions and was subdivided into four sections with each section consisting of three questions. Each section addressed one of the four email design cues. The first section addressed source address, the second section addressed grammar and spelling, the third section addressed urgency cues, and the fourth section addressed title/subject line. For each section, all three questions were identical, asking respondents how likely they were to respond to the accompanying email while paying particular attention to the design cue associated with that section. For example, for the first section, all three questions asked the respondents “Paying particular attention to the email source (sender address) [emphasis based on the original question in part two], how likely are you to respond to the email below?” Similar to the first part of the SSS, accompanying each question was an example of a cyber sextortion email, and a 4-point Likert scale on which respondents could record their response to each question (1 = Very Unlikely, 2 = Unlikely, 3 = Likely, and 4 = Very Likely). Additionally, for this second part of the questionnaire, all the cyber sextortion emails were predesigned, although the content of the emails was based on real cyber sextortion emails. Other than the content of the email, the information in the sender line, and the information in the title/subject line, all emails were kept identical in color and layout to avoid adding any confounding variables. By asking respondents to focus their attention on the design cues before answering how likely they would be to respond to each question’s associated email, the effect that paying attention to each design cue has on respondents’ likelihood of responding to cyber sextortion emails could be measured and compared with each of the other design cues. The effect of paying attention to each design cue could also be measured and compared to the effect of not paying specific attention to any design cue, as was measured in the first part of the SSS.

3.3. Procedure

Human Research Ethics approval was obtained for the study. The survey was conducted online, with participants signing up for the study, and data were collected via Qualtrics (an online-based survey, research, and experience management platform). After participants accessed the survey, they were required to read a participant information sheet that gave a basic summary of the study and outlined what participants would be expected to do. Participants were then required to sign a consent form. After this process, participants answered six demographic questions including gender; age; whether they have had any cybersecurity education or training; experiences with phishing or scam emails; experiences with cyber sextortion scams; and experiences with any other form of cyberbullying or harassment. Following this, participants completed the SRHI and the SSS questionnaires. After the survey was completed, participants were debriefed on the aims of the study and thanked for their time.

3.4. Data Coding

In order to analyze participants’ susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks using the SSS, susceptibility scores for each email design cue for each participant had to be computed. To do this, participants’ answers of how likely they were to respond to each cyber sextortion email were averaged for each email design cue. That is, all eight questions from the first part of the survey were averaged for each participant to give a susceptibility score for when attention to email design cues was not specified, and all three questions from each of the four sections of the second part of the survey were averaged for each participant to give four susceptibility scores for when attention was focused on email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line, respectively. Possible scores ranged from 1 = very unlikely to respond to 4 = very likely to respond.

To analyze participants’ email habits, each statement on the modified version of the SRHI was grouped into three different categories of email habits. The first seven statements consisted of habits including the frequency and cognitive automaticity with which participants used emails. These were grouped into the category General Email Habits. The next 12 statements consisted of participants’ email security habits and were grouped into the category Security Email Habits. The last four statements consisted of participants’ habit of paying attention to each of the email design cues (email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line) and so were grouped into the category Attentional Email Habits. Each participant’s score for each category was calculated by adding their answers to all statements in each category. General email habits scores ranged from 7 = low frequency and cognitive automaticity to 28 = high frequency and cognitive automaticity; security email habits ranged from 12 = low security to 48 = high security; and attentional email habits ranged from 4 = strong habit of paying attention to email design cues to 16 = weak habit of paying attention to email design cues.

4. Results

4.1. Data Screening

One response was removed from the analysis due to a failure to consent to participate, resulting in a sample size of 86. All data entries appeared accurate on visual inspection. There were no missing data. Seven outliers were identified by calculating the z-scores for each participant’s susceptibility score when asked to pay attention to each of the cyber sextortion email design cues (email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line) and to the condition where no design cue was specified. On the recommendations of [28], z-scores in excess of ±3.29 (p > 0.001) were considered outliers and made to be one unit more extreme than the next most extreme score. The statistical distribution of scores for each of the email design cues departed from normality on both a formal statistical test of normality and a visual inspection of each design cue’s histogram.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 2, the mean susceptibility score when participants were not instructed to pay attention to any email design cue was 1.226 (SD = 0.474). The mean susceptibility scores when participants were instructed to pay attention to email source was 1.314 (SD = 0.625), grammar and spelling was 1.299 (SD = 0.556), urgency cues was 1.322 (SD = 0.587), and title/subject line was 1.357 (SD = 0.631). Also shown in Table 2 are the mean scores for participants’ email habits.

Table 2.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of susceptibility scores for each design cue condition and scores for each email habits category.

4.3. Impact of Design Cues on Sextortion Susceptibility

4.3.1. Parametric Testing

Susceptibility scores for the email design cue conditions were analyzed using a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Although the assumption of normality was not met for the distribution of scores for any of the email design cue conditions, the ANOVA family of statistical tests is considered to be robust with regard to normality when the sample size is greater than 30, the sample sizes between groups are relatively similar, there are no outliers, and when the error variance in the ANOVA test is 20 degrees of freedom or greater [28,29]. All these characteristics were met in the current analysis. In addition to the assumption of normality, a second assumption of sphericity was also not met for the current analysis using Mauchly’s test of sphericity; therefore, a Greenhouse–Geisser correction was made to the degrees of freedom (see Table 3).

Table 3.

ANOVA tests of within-subjects effects.

With alpha set to 0.05, the result, F(3.52, 298.75) = 4.24, p = 0.004, ƞp2 = 0.05, showed a statistically significant difference for susceptibility scores amongst the email design cue conditions (see Table 3).

Post hoc comparison tests were conducted between the email design cue conditions most relevant for the current study’s hypotheses; that is, the condition in which no email design cue was specified compared to each of the other email design cue conditions. As four post hoc comparison tests were conducted, a Bonferroni adjusted alpha of 0.0125 was made to maintain the familywise error rate at 0.05. Results showed that when participants focused attention on the email source, they were more susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks than when attention to email source was not specified (MDiff = 0.088, p = 0.011, 95% CI [0.021, 0.156]). Similarly, when participants focused attention on the title/subject line, they were more susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks than when attention to title/subject line was not specified (MDiff = 0.131, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.052, 0.210]). However, there was no significant difference when participants focused attention on grammar and spelling compared to when attention to grammar and spelling was not specified (MDiff = 0.073, p = 0.028, 95% CI [0.008, 0.138]), nor when participants focused attention on urgency cues compared to when attention to urgency cues was not specified (MDiff = 0.096, p = 0.018, 95% CI [0.017, 0.175]). See Table 4 for ANOVA post hoc comparison test results.

Table 4.

ANOVA post hoc comparison test results.

4.3.2. Non-Parametric Testing

As the susceptibility score distributions for each of the email design cue conditions were not normally distributed, a Friedman nonparametric test was also conducted to determine any significant differences between the susceptibility scores for each of the email design cue conditions and to provide a comparison for the findings of the ANOVA test results shown above. As the Friedman nonparametric test uses ranks rather than raw scores in its calculation, it does not require the assumption that the data are normally distributed [29]. In addition, as Kendall’s W is a common measure of effect size for the Friedman nonparametric test, it was used to provide a measure of effect size in the current analysis.

With alpha set to 0.05, the result, χ2 (4, N = 86) = 13.08, p = 0.011, W = 0.04, showed a statistically significant difference for susceptibility scores amongst the email design cue conditions (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Friedman nonparametric test results.

Four post hoc comparisons using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test were conducted between the email design cue conditions most relevant for the current study’s hypotheses, i.e., the condition in which no email design cue was specified compared to each of the other email design cue conditions. As four post hoc comparison tests were conducted, a Bonferroni adjusted alpha of 0.0125 was made to maintain the familywise error rate at 0.05. The significance of each of the email design cues was similar to the ANOVA analysis. When participants focused attention on the email source, they were more susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks than when attention to the email source was not specified, z (N = 86) = 2.79, p = 0.005, r2 = 0.05. With regard to getting participants to focus their attention on the title/subject line, they were found to be more susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks than when attention to title/subject line was not specified, z (N = 86) = 3.13, p = 0.002, r2 = 0.06. However, there was no significant difference when participants focused attention on grammar and spelling compared to when attention to grammar and spelling was not specified, z (N = 86) = 2.47, p = 0.014, r2 = 0.04, nor when participants focused attention on urgency cues compared to when attention to urgency cues was not specified, z (N = 86) = 2.47, p = 0.014, r2 = 0.04. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test results.

4.4. Influence of Email Habits on the Impact of Design Cues for Sextortion

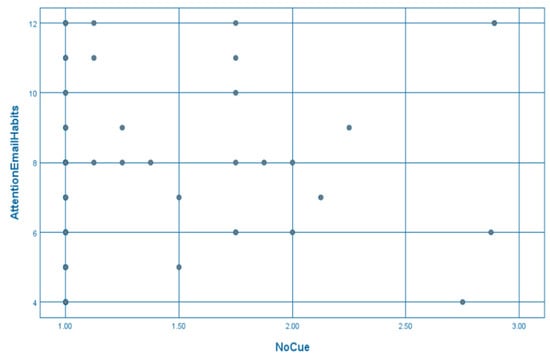

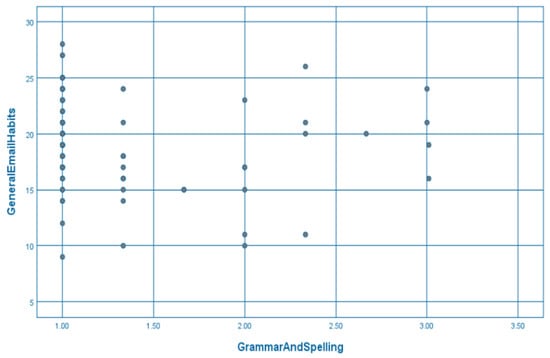

A number of correlational analyses were conducted between susceptibility scores for each of the email design cue conditions and participants’ scores on each of the email habit categories measured by the modified version of the SRHI (general email habits, security email habits, and attentional email habits). As email habits may influence susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks, correlational analyses were conducted to gather foundational information that might help account for possible discrepancies in measuring the effect of attention to specific design cues within cyber sextortion emails on participants’ susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was used for the analysis because it does not require the assumption that scores for each correlated variable be normally distributed [29], and since the susceptibility distributions for each email design cue condition departs from normality, Spearman’s rho was considered the most appropriate correlational measure for the current analysis. A visual inspection of scatterplots also indicated some evidence of heteroscedasticity (see Figure 3 and Figure 4), meaning that results should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of participants’ attentional email habits and cyber sextortion susceptibility scores when no email design cue was specified.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of participants’ general email habits and cyber sextortion susceptibility scores when attention was focused on grammar and spelling.

With alpha set to 0.05, results showed a weak, positive relationship between participants’ attentional email habits, and susceptibility scores when attention to cyber sextortion email design cues was not specified, r(84) = 0.22, p = 0.045. As the questions used to measure attentional email habits asked how rarely participants pay attention to email design cues when checking their emails, this result suggests that people who rarely pay attention to email design cues are more susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks than people who frequently pay attention to email design cues, but only when not primed to pay attention to them. Results also showed a weak negative relationship between participants’ general email habits and susceptibility scores when attention was focused on grammar and spelling, r(84) = −0.24, p = 0.027. This suggests that people who use emails frequently and with less cognitive effort are less susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks when focusing on grammar and spelling than people who use emails infrequently and with more cognitive effort. No other correlations were significant. All inter-correlations between susceptibility scores for each of the email design cue conditions and scores for each of the email habit categories are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Inter-correlations between susceptibility scores for each design cue condition and scores for each email habits category.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend our understanding of cyber sextortion by using the results obtained from this study and knowledge surrounding social engineering attack-based techniques such as phishing, to investigate the effects of message-related factors on cyber security behavior and susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks. This study examined the effect that focusing attention on a number of email design cues has on people’s potential to respond to, and hence be susceptible to, cyber sextortion attacks. The email design cues, identified in the IIPM, that were examined included email source, grammar and spelling, urgency cues, and title/subject line. The following results were shown with regard to the study’s hypotheses: (1) hypothesis one—focusing attention on the email source in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as less likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on the email source—was not supported; (2) hypothesis two—focusing attention on grammar and spelling in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as less likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on grammar and spelling—was not supported; (3) hypothesis three—focusing attention on the title/subject line in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as more likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on the title/subject line—was supported; and (4) hypothesis four—focusing attention on urgency cues in cyber sextortion emails will correlate with participants rating the email as more likely to be responded to than not focusing attention on urgency cues—was not supported. As previously indicated in the current study section, the null hypotheses are also relevant on the basis of participants still being susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks, particularly in cases where non-significance was observed.

The results for hypothesis one showed that when participants focused on the source address in cyber sextortion emails, they were not less likely to be susceptible to cyber sextortion attacks compared to when no email design cue was specified. In fact, the results showed that they were more likely to be susceptible when focusing on the email source. This is in contradiction to previous research on phishing susceptibility which showed that source address has the potential to reveal the authenticity of phishing emails and thus alert potential victims to the deception, reducing the likelihood that victims will respond and hence be susceptible [30]. The discrepancy between the current study’s results and that of past studies with regard to source address may be due to differences in the nature of cyber sextortion attacks as opposed to phishing attacks. In phishing attacks, the perpetrator is often attempting to impersonate another individual or business in order to hide the malicious nature of the email. In cyber sextortion attacks, the malicious nature of the email is emphasized in order to threaten the victim to respond. Thus, victims are already alerted to the threat of the email. In addition, focusing attention on the email source in cyber sextortion attacks may help personalize the email, reinforcing to the victim that the perpetrator is a real, autonomous entity that can do damage. In any case, this result highlights the importance of the email source as a design cue capable of fooling victims into responding to cyber sextortion attacks.

For the second and third hypotheses, the results indicated that when attention was focused on grammar and spelling, or when attention was focused on urgency cues, susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks did not differ significantly compared to when attention to email design cues was not specified. These results also depart from previous research on phishing susceptibility including the IIPM which showed that, similar to email source, attention to grammar and spelling should reveal the authenticity of the email and thus alert victims to the deception, while urgency cues should elicit feelings of threat and fear, encouraging victims to use heuristic cognitive decision-making strategies that are more amenable to persuasive tactics and thus elicit compliance [30]. One possibility for the discrepancy may have to do with the way the current study was conducted. While participants were instructed in different sections of the survey to focus on each email design cue, and in one section of the survey attention to email design cues was not specified, the characteristics of the cyber sextortion emails themselves were not systematically manipulated on any variable. Because urgency cues and spelling and grammatical errors are highly salient aspects of the email text, it is possible that participants focused on these design cues even when they were not instructed to. Thus, spelling and grammar and urgency cues may not have been measured exclusively in the sections in which they were specified. In any case, similar to email source, the fact that these design cues did not decrease susceptibility highlights the importance of spelling and grammar and urgency cues as design cues capable of fooling victims into responding to cyber sextortion attacks.

Hypothesis four’s results revealed that when attention was focused on the title/subject line, susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks was significantly increased compared to when attention to email design cues was not specified. The title/subject line is the only email design cue examined in the current study that follows the predictions of the IIPM model of phishing susceptibility. It would appear then that the title/subject line continues to act as a lure in cyber sextortion emails as it does for phishing emails, alerting victims to the relevance of the message contained in the email, and thus increasing susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks. Cyber sextortion emails (as with phishing emails) often also contain urgency cues within the title/subject line in addition to the email message. Therefore, it is also possible that the title/subject line directly increases susceptibility through the use of its own urgency cues in addition to the urgency cues within the email message. Similar to the other email design cues, the fact that attention to the title/subject line significantly increases susceptibility, this result highlights the importance of the title/subject line as a design cue capable of fooling victims into responding to cyber sextortion attacks.

Results for the fifth hypothesis further exhibited that a number of email habit categories significantly correlated with cyber sextortion susceptibility scores for a number of email design cues. Firstly, attentional email habits correlated with susceptibility scores when attention to design cues was not specified, meaning that people who have a habit of not paying attention to email design cues are more likely to be susceptible than people who do. This appears to be contradictory to the results above that show that attention to particular design cues increases susceptibility. The result, however, is consistent with previous research which shows that email habits increase susceptibility to phishing attacks [31]. A possible explanation for this is that people who habitually pay attention to design cues may also be more risk aversive, and thus less likely to respond to cyber sextortion emails. Secondly, general email habits negatively correlated with susceptibility scores when attention was focused on grammar and spelling, implying that people who use emails more frequently and with less cognitive effort are less susceptible when paying attention to grammar and spelling. A possibility is that people who use emails with less cognitive effort are more likely to interpret bad grammar and spelling as evidence of a cyber sextortion email’s inauthenticity, as predicted by the IIPM.

6. Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of this study is that the methodology consisted entirely of a survey-based correlational design. While the researchers acknowledged that a sample of 86 respondents could make a statistical difference in terms of generalisability, the study has shown to be valid in deducing generalized perspectives since its findings can be applied to the population due to generalization also being a measure of how useful the result of a study is for a specific population. The results of the study apply to many different types of people susceptible to different cybercrime (sextortion and phishing) situations. Attention to each of the email design cues was not experimentally manipulated and outside extraneous variables that may have confounded the results were not experimentally controlled. It therefore cannot be entirely assumed that attention to the email design cues that were measured actually caused the changes in cyber sextortion susceptibility scores that were observed. Future research should attempt to use an experimental methodology to determine whether the relationship between attention to email design cues and susceptibility to cyber sextortion attacks is causal and whether the effect of each of the design cues continues to show the same results. Experimental methodologies have been used in past research on phishing susceptibility to provide more stringent control measures. Another limitation is that the survey was a self-report questionnaire, and participants knew in advance that the study was investigating the topic of cyber sextortion. This would have primed participants to the knowledge that the emails were deceitful, increasing suspicion and causing participants to rate their level of susceptibility as less than it would otherwise have been [32]. Future research should attempt to remove participant expectations from measurements of cyber sextortion susceptibility.

7. Implication and Conclusions

The results of this study have significant implications when investigating susceptibility or vulnerabilities to cyber sextortion. It can be considered that the more vulnerable a person is online, the more at risk they are to cyber sextortion attacks as the lack of understanding of email design cues that cyber criminals apply can leave people more susceptible. Additionally, the lack of paying attention to these design cues, as well as poor email security habits, would allow further developments of sophisticated cyber sextortion attack techniques for extortion at an enterprise level [33,34]. Overall, from the results of this study, security awareness and training programs must be designed in a manner that incorporates attention to email design cues and habits to minimize or mitigate vulnerabilities to cyber sextortion attacks both at individual and organizational levels.

In conclusion, cyber sextortion attacks are on the rise and affect millions of people, especially with the evolving trends of “Work from Home” due to pandemics such as COVID-19, and the consumerization of the Internet of Things (IoT) [35,36]. However, sextortion attacks and individual susceptibility to these attacks are dramatically understudied. As such, little is known about which aspects of cyber sextortion attacks are likely to cause victims to be susceptible to them. This study is one of the first to investigate message-related factors in cyber sextortion email design and its effect on individuals’ susceptibility to being victimized by cyber sextortion attacks. Four email design cues were tested for their effect on cyber sextortion susceptibility—design cues that had previously been shown to affect susceptibility to phishing attacks. While not all design cues significantly increased susceptibility, the fact that they were all present in email designs to which participants were susceptible shows their importance in deceiving people into responding to cyber sextortion attacks. As such, message-related factors are an important focus for future research on cyber sextortion attacks, as well as control mechanisms to mitigate the risks of these malicious attacks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and A.B.; methodology, B.P. and A.B.; software, B.P.; validation, B.P. and A.B.; formal analysis, B.P.; investigation, B.P. and A.B.; resources, B.P.; data curation, B.P. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and A.B.; visualization, B.P. and A.B.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, B.P. and A.B.; funding acquisition, B.P and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Western Sydney University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the journal for the opportunity to publish an open access paper, and many thanks to the outstanding reviewers for their hard work and feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Definitions. Available online: https://www.cybercivilrights.org/definitions/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Wolak, J.; Finkelhor, D. Sextortion: Findings from a Survey of 1631 Victims 2017. Available online: https://respect.international/sextortion-findings-from-a-survey-of-1631-victims/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- FBI, This Week: Sextortion Reports on the Rise. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/audio-repository/ftw-podcast-sextortion-scam-081018.mp3/view (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Sextortion Affecting Thousands of U.S. Children 2016. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices/charlotte/news/press-releases/sextortion-affecting-thousands-of-u-s-children (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Wittes, B.; Poplin, C.; Jurecic, Q.; Spera, C. Sextortion: Cybersecurity, Teenagers, and Remote Sexual Assault 2016. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/sextortion-cybersecurity-teenagers-and-remote-sexual-assault/ (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Vishwanath, A.; Herath, T.; Chen, R.; Wang, J.; Rao, H.R. Why Do People Get Phished? Testing Individual Differences in Phishing Vulnerability within an Integrated, Information Processing Model. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, M.; Jerram, C.; Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Butavicius, M. Why Do Some People Manage Phishing e-Mails Better than Others? Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2012, 20, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.T.; Marett, K. The Influence of Experiential and Dispositional Factors in Phishing: An Empirical Investigation of the Deceived. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastdrager, E.E.H. Achieving a Consensual Definition of Phishing Based on a Systematic Review of the Literature. Crime Sci. 2014, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, K.L.; Yong, K.S.; Tan, C.L. A Survey of Phishing Attacks: Their Types, Vectors and Technical Approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 106, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, V. A Review on Phishing Attacks and Various Anti Phishing Techniques. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2016, 139, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, J.L., Jr.; Bailey, J.L.; Courtney, J.F. A personality based model for determining susceptibility to phishing attacks. In Proceedings of the Southwest Decision Sciences Institute Annu. Meeting (SDSI ’09), Oklahoma, OK, USA, 24–28 February 2009; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Investigating the Mediating Role of Social Networking Service Usage on the Big Five Personality Traits and on the Job Satisfaction of Korean Workers. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2019, 31, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, B.; Huang, W. A Study of Social Engineering in Online Frauds. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.J.; Polage, D. How Persuasive Is Phishing Email? the Role of Authentic Design, Influence and Current Events in Email Judgements. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 38, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M. Wisecrackers: A Theory-Grounded Investigation of Phishing and Pretext Social Engineering Threats to Information Security. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008, 59, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.E.; Grazioli, S.; Jamal, K.; Zualkernan, I.A. Success and Failure in Expert Reasoning. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1992, 53, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, D.B.; Burgoon, J.K. Interpersonal Deception Theory. Commun. Theory 1996, 6, 203–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.; Zajonc, R.B. The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lindzey, G., Aronson, E., Eds.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 137–230. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath, A. Habitual Facebook Use and Its Impact on Getting Deceived on Social Media. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 20, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, M.; Tsow, A.; Shah, A.; Blevis, E.; Lim, Y.-K. What Instills Trust? A Qualitative Study of Phishing. Financ. Cryptography and Data Security; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Stajano, F.; Wilson, P. Understanding Scam Victims. Commun. ACM 2011, 54, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.; Vishwanath, A.; Rao, R. A User-Centered Approach to Phishing Susceptibility: The Role of a Suspicious Personality in Protecting against Phishing. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimighahnavieh, M.A.; Luo, S.; Chiong, R. Deep Learning to Detect Alzheimer’s Disease from Neuroimaging: A Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 187, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, A.; Harrison, B.; Ng, Y.J. Suspicion, Cognition, and Automaticity Model of Phishing Susceptibility. Commun. Res. 2016, 45, 1146–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Orbell, S. Reflections on Past Behavior: A Self-Report Index of Habit Strength1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, A.M. Foolproof Guide to Statistics Using IBM SPSS; Pearson Australia: Frenchs Forest: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, K.; McCormac, A.; Pattinson, M.; Butavicius, M.; Jerram, C. Phishing for the Truth: A Scenario-Based Experiment of Users’ Behavioural Response to Emails. In Security and Privacy Protection in Information Processing Systems; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 366–378. [Google Scholar]

- Tsow, A.; Jakobsson, M. Deceit and Deception: A Large User Study of Phishing; Technical Report TR649; Indiana University: Bloomington, Indiana, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, C.I.; Fischhoff, B.; Davis, A. Quantifying Phishing Susceptibility for Detection and Behavior Decisions. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2016, 58, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadoria, R.S.; Chaudhari, N.S. Pragmatic Sensory Data Semantics with Service-Oriented Computing. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2019, 31, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C.; Seow, Y.M. Protective Measures and Security Policy Non-Compliance Intention. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2019, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.; Mahadevan, V. A Cloud Based Conceptual Identitymanagement Model for Secured Internetof Things Operation. J. Cyber Secur. Mobil. 2018, 8, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.J.; Morgan, P.L.; Joinson, A.N. Press Accept to Update Now: Individual Differences in Susceptibility to Malevolent Interruptions. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 96, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).