Abstract

The Data Distribution Service (DDS) for real-time systems is an industrial Internet communication protocol. Due to its distributed high reliability and the ability to transmit device data communication in real-time, it has been widely used in industry, medical care, transportation, and national defense. With the wide application of various protocols, protocol security has become a top priority. There are many studies on protocol security, but these studies lack a formal security assessment of protocols. Based on the above status, this paper evaluates and improves the security of the DDS protocol using a model detection method combining the Dolev–Yao attack model and the Coloring Petri Net (CPN) theory. Because of the security loopholes in the original protocol, a timestamp was introduced into the original protocol, and the shared key establishment process in the original protocol lacked fairness and consistency. We adopted a new establishment method to establish the shared secret and re-verified its security. The results show that the overall security of the protocol has been improved by 16.7% while effectively preventing current replay attack.

1. Introduction

With the Internet of Things (IoT) technology’s rapid development, IoT devices are being widely used and integrated into an increasing number of applications, the basic components of IoT devices are numerous terminals, transmission networks and clouds, which correspond to the three layers of the IoT system’s perception layer, network layer, and application layer [1,2]. Each layer should apply some security rules to an IoT implementation for it to be secure. Only by resolving the security issues related to IoT can the future of IoT frameworks be guaranteed [3]. Application scenarios and the security of different levels of protocols have become crucial considerations as a result of the development of IoT technology. In many devices, IoT devices are connected through insecure connections over the Internet. For many IoT applications, including important industrial, medical, and personal ones, security is a crucial aspect.

IoT protocols are generally divided into two categories, one is the transmission protocol and the other is the communication protocol. The DDS protocol is a communication protocol, and similar protocols include Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP), Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), etc. DDS, MQTT, and AMQP are all based on the publish/subscribe model [4,5]. The publish/subscribe framework has the characteristics of service self-discovery, dynamic expansion, and event filtering. It solves the problem of rapid acquisition of data sources, addition and exit of things in the application layer of the IoT system, interest subscription, reducing bandwidth traffic and other issues, to achieve loose coupling in space, loose coupling in time, and loose coupling in synchronization. With the help of service policies, DDS can effectively control and manage the use of resources, such as network bandwidth and memory space, and can also control data reliability, real-time and data survival time. By using these service quality policies flexibly, DDS not only in the narrowband wireless environment, but also in the broadband wired communication environment, a data distribution system that meets real-time requirements can be developed.

At present, there is a lack of research on the security issues of the DDS protocol. For example, there is a lack of formal security analysis and security mechanism evaluation. To solve this problem, in this paper we will use the protocol formal analysis method to model the DDS protocol and conduct security assessment. The formal analysis method refers to the method of describing the system model by mathematical or logical methods, and verifying whether the system meets the requirements through a certain form of reasoning. The use of formal analysis methods for security protocol verification was first proposed by Needham and Schroeder [6], and later adopted by Dolev and Yao and published important results in 1983 [7]. The formal analysis tool in this paper uses CPN Tools, which can dynamically simulate the model with the help of CPN Tools [8,9]. The visual interface allows users to observe the execution process of each step of the model and judge whether there are security vulnerabilities in the protocol model through the state space [10].

Specifically, this paper contributes to three areas:

- 1.

- We investigate the security of the DDS protocol using formal model identification based on CPN theory and Dolev–Yao adversaries;

- 2.

- The CPN modeling tool is used to model the DDS protocol, and the model’s correctness is checked. When the Dolev–Yao model is used to assess the protocol’s security, it is discovered that there are security flaws;

- 3.

- In order to address the protocol’s security flaws, a new improved solution is put forth, and its security is confirmed by simulating an adversary attack model.

The roadmap of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses the current related work. Section 3 discusses the choice of tools and methods, the CPN model, and the working mechanism of the protocol. Section 4 discusses the initial description of the system and how to use CPN Tools to build an initial model and verify it. Section 5 discusses the verification of protocol security by adding an attacker model. Section 6 discusses and establishes a new protocol reinforcement scheme and verifies its security. Section 7 discusses whether adding a timestamp affects the structure of the packet changes and defines the size of the timestamp, and proposes the next step to simulate the protocol by using the CANoe platform. Finally, we conclude and present areas for future works.

2. Related Work

Security studies are critical to the DDS protocol. Based on the analysis of the security threats faced by DDS and the corresponding strategies, Shen et al. [11] propose a DDS secure communication middleware model, including identity authentication, authority control, and data encryption and decryption functions. Although this method combines the discovery mechanism and Quality of Service (QoS) negotiation mechanism of DDS, realizes the custom configuration of security protection level and encryption algorithm, and meets the flexibility and efficiency requirements of upper-layer applications, it will make the discovery of DDS secure communication middleware match. There is a small increase in latency and publish–subscribe latency. Zhen et al. [12] propose a way to expand the combination of DDS built-in topics and digital certificates to realize DDS identity authentication. Although this method ensures the security of the data distribution service, it consumes a lot of computing time and affects the real-time performance of the system. Focusing on the lack of fairness, consistency, and integrity of identity authentication and key agreement protocols, Li et al. [13] propose a high-security identity authentication protocol based on Diffie–Hellman key exchange and asymmetric encryption. Although this method solves the security problems, such as lack of fairness in key negotiation, inability to verify the consistency of shared key, and lack of integrity of session process in the original protocol, it is not flexible enough for users to configure security services. Beckman et al. [14] propose a new method sDDS-Sec, which is a method to apply DDS security extensions to sDDS. Although this approach enables secure and reliable pub/sub communication in low-power wireless networks in IoT scenarios, the availability of platforms is not widely applicable. Michaud et al. [15] details five attack methods that may be used in client-side attacks against DDS-based systems, which are based on 5 DDS security questions [16]. Through modeling and demonstration, then combined into an end-to-end verification scenario, the experiments show that these security issues are not addressed, or may reveal new security issues. The security functions and threats of protocol standards are well investigated and deduced in the literature. However, the security characteristics of protocol stacks can only be ascertained by modeling and demonstrations rather than through rigorous formal analysis. Ioana et al. [17] combined three communication protocols suitable for automotive and IoT scenarios. A multi-protocol gateway is proposed to successfully facilitate the data exchange between different entities, expand the applicability of the target technology in V2X scenarios, and at the same time confirm the compatibility between protocols. Kim et al. [18] proposed a new approach to improve the authorization of the DDS security model using ABAC and formalized the decision-making process with a proof of decidability. Therefore, it is crucial to use formal methods to examine security vulnerabilities that arise during protocol interaction [19].

In summary, DDS protocol security analysis lacks formal verification. Based on the CPN theory, this paper simulates the interaction process of the DDS protocol, and introduces attackers by simulating the interaction process of the protocol to discover the security problems of the protocol itself. Then we propose a new scheme based on protocol standard improvement and verify its security. The new scheme is verified to be more secure.

3. Related Foundation

3.1. Formal Modeling Methods Comparison

Protocol engineering uses formal description technology to strictly design and maintain various activities of the protocol, and establishes an accurate protocol model to verify the logical correctness of the protocol. At present, the more popular formal methods for network protocols include state machines, temporal logic, Petri nets, etc., and these methods have their own characteristics.

Protocol state machines, are finite state machines or automata that describe the message sequences that can occur as sessions for some protocol. Traditional state machines can adeptly model many constructs and extract and analyze their behavior. Unfortunately, state machines do not scale well due to state space explosion. In addition, the state machine is only suitable for describing small and simple protocols, and it is single-threaded, which has limited ability to describe the complex systems of many large-scale applications in the real world. When analyzing and verifying the state machine model, reachability analysis technology is usually used, which needs to manually generate a state reachable tree, which is prone to state space explosion and cannot prove the activity of the protocol. Therefore, simply using the state machine theory to model the multi-concurrent session system of the security protocol will not be effective.

Temporal logic is an extension of modal logic. Temporal logic is mature in application and has strong mathematical abstraction ability. It focuses on describing the system by defining externally visible action events of the system, and does not care about the details of internal changes in the protocol. It is easy to describe the activity of the protocol, it is also easy to verify the protocol model. However, it is too abstract to describe the logical structure of the protocol.

The Petri net model is based on the concept of concurrency, and the description system is simple and intuitive. At the same time, it has a complete analysis method and mature analysis tools, and is widely used in distributed software systems, parallel computing, network communication protocols and other fields. CPN adds a color set to classify tokens on the basis of traditional Petri nets, which requires the definition of variables and functions to realize the flow of different tokens on the arc, thereby improving the expressive ability of Petri nets and the ability to describe complex systems. CPN supports the hierarchical abstraction technology of models, which can model complex system behaviors at different levels of abstraction, and supports efficient model analysis and confirmation. CPN is a concurrent and typed enhancement of a state machine, with a mature modeling platform, and CPN Tools is a powerful modeling and analysis tool set for editing, simulating, and analyzing the state space of the CPN model. Combined with the programming language CPN Markup Language (ML), its ability to describe large and complex systems is greatly improved.

Through comparative analysis, this paper believes that the CPN method has more advantages in describing network protocols. Although CPN is similar to a state machine, it is suitable for complex concurrent protocols due to its powerful and easy-to-understand state space analysis capabilities. The state space explosion is easier to manage, and DDS is a large and complex protocol, so we use CPN to simulate this agreement.

3.2. Tools Comparison

The research object of this paper is the security mechanism in the protocol. The analysis focuses on the security verification of the security protocol to find the protocol security vulnerabilities, so it is assumed that the communication is reliable. Therefore, network simulation tools, such as GNS and NS3 [20] are not used to study any communication protocol or communication mechanism.

The current mainstream protocol formal modeling tools, such as Scyther [21], Tamarin [22], ProVerif [23] and CPN Tools [24]. Among them, the Scyther tool is based on the SPDL language to model the protocol; the Tamarin tool describes the protocol process based on multiple sets of rewriting rules, and uses first-order logic to quantify protocol messages and time nodes, thereby realizing the description of the protocol attributes; the Proverif tool models the protocol based on the rule form of the logic programming language Prolog, and infers whether an event will occur according to some rules; the CPN Tools models the protocol based on the colored Petri net. Although they can both model protocols in different ways, CPN has certain advantages compared with other automatic protocol security verification tools. The tool comparison is as follows:

The Scyther tool is insufficient in the expansion of algebraic properties, and cannot detect attacks containing algebraic properties. The attack model of the Tamarin tool requires manual input, which is difficult to operate. The ProVerif tool cannot discover the loopholes in the protocol, but can only prove the security properties that the protocol satisfies. CPN Tools calculates the state space and generates a state space report by creating a hierarchical CPN reachability graph. At the same time, the high degree of freedom in the CPN modeling process has become one of its advantages. The state space is completely controlled by the modeler himself, and exclusive modeling and analysis methods can be implemented for different protocols. This is why CPN protocol verification is often more effective than automated protocol verification tools, so we use CPN Tools to simulate the protocol.

3.3. CPN Modeling Tool

The CPN Tools is a special simulation system that uses the language of Petri nets for model representation. The tools were developed by Aarhus University in Denmark based on Design/CPN, and the Graphical User Interface (GUI) was designed using good human–machine interface technology, which not only enables editing, simulation, and analysis of colored Petri nets, but also supports the Timed Colored Petri Nets (TCPN) and the Hierarchical Colored Petri Nets (HCPN). With the help of CPN Tools, users can easily model, simulate, and analyze parallel systems [25,26]. The CPN Tools proposes a very powerful class of Petri nets for model description. TCPN exploit the model’s notion of time to represent the duration of actions in real-world objects. HCPN provides the construction of complex models. In CPN Tools, the model description language constitutes a combination of two programming languages, including Petri net graphs and CPN ML. In addition to state space generation and analysis, it offers incremental syntax checking and code generation functions for network development. Analyzing the state space reports will enable a thorough security examination and assessment of the build models.

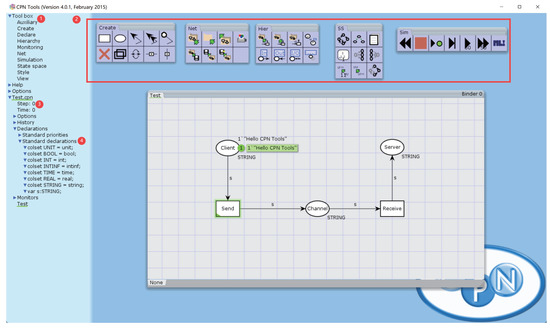

We use a practical case to show the user interface and how to use CPN Tools, Figure 1 represents the initial state of the simple model of the protocol communication process. The red number 1 indicates the tool box. The red number 2 indicates the specific toolbar function, we use the Create toolbar to build our model, where ellipses represent places and matrices represent transitions. The Sim is used to run the model, determine whether there are loops in the model, etc. The Hier toolbar is used to connect layers, assign ports, etc. The SS toolbar is used to run the model state space and generate state space reports. The red number 3 indicates the number of steps to run and the red number 4 indicates the color set declaration.

Figure 1.

Simple model initial state of protocol communication process.

Figure 2 represents the final state of the simple model of the protocol communication process. We see that the message has been passed from the client to the server and the number of steps has changed to 2. The red number 1 represents the state space, we can see the number of nodes, the number of arcs, boundedness properties and whether the state space is complete. It can see that the number of nodes and the number of arcs are the same, indicating that there is no loop and the protocol is completed.

Figure 2.

Simple model final state of protocol communication process.

From Figure 1 we can see the default declared color set definition. The color sets defined by the CPN Tools mainly include two types of basic color sets and compound color sets. Composite color sets are obtained by performing some operations on basic color sets, the most commonly used of which are product color sets and list color sets. The color sets that can be defined by CPN Tools are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Color set defined by CPN Tools.

3.4. DDS Protocol and Standard Architecture

DDS [27] is data-centric, using a publish/subscribe communication model, which has the advantages of real-time, dynamic, reliability, scalability, and flexibility [28], but faces security threats, such as unauthorized subscription, unauthorized publication, unauthorized access to data, and tampering and replay. To deal with the above security issues, the Object Management Group (OMG) released the DDS version 1.0 and 1.1 security specifications in 2016 and 2018, respectively, adding security mechanisms to DDS to deal with security threats [11,29,30]. However, security flaws remain unresolved. In addition, DDS is used in highly dynamic distributed systems, the network topology is dynamically discovered, the connections between nodes are established point-to-point, there is no central server as a single point of failure, and there is a rich set of QoS policies, which is why DDS commonly used for reasons in industrial environments.

Currently, both DDS and Scalable service-Oriented MiddlewarE over IP (SOME/IP) have been incorporated into the AUTOSAR platform standard [17]. SOME/IP and DDS are the two most commonly used communication protocols in autonomous driving. From the perspective of autonomous driving, both SOME/IP and DDS protocols have good practicability, and SOME/IP can be used as a substitute for DDS protocol. SOME/IP is specially designed for the automotive field. It defines a set of communication standards for the needs of the automotive field, and has been deeply cultivated in the automotive field for a long time; DDS is an industrial-level strong real-time communication standard. The adaptability to the scene is relatively strong, but special tailoring is required when it is used in the field of automobile/autonomous driving. However, from the perspective of the trend of the latter, the market share of DDS will be larger than that of SOME/IP in the future.

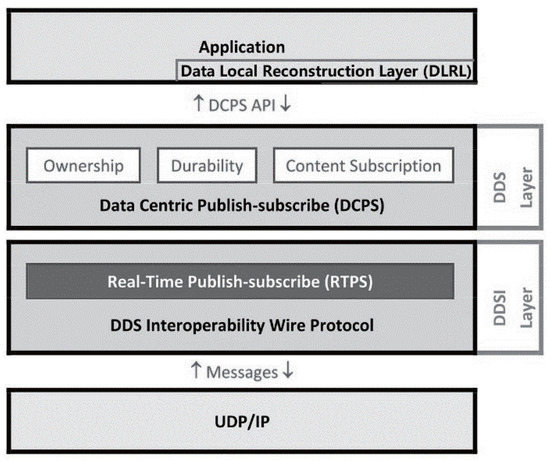

The OMG DDS standard consists of the DDS Interoperability Wire Protocol (DDSI) layer and the DDS layer. The DDSI layer specifies the network transport layer and the DDS layer specifies the data center publish–subscribe behavior and DDS API [31]. Figure 3 shows the stack view of the OMG DDS standard architecture [32]. The DDS specification is divided into two layers [33]: one is the Data-Centric Publish–Subscribe (DCPS) layer [34], and the other is the Data Local Reconstruction Layer (DLRL). The DCPS layer is the core and foundation of DDS and provides the basic services of communication; the DLRL layer abstracts the services provided by the DCPS layer and establishes the mapping relationship with the underlying services in the DLRL layer.

Figure 3.

DDS standard architecture.

The core of the DDS protocol is built around DCPS. This layer defines how DDS sends data from the publisher to the subscriber. The latest specification proposes a new concept, the global data space, which is the top-level abstraction of DDS and stores all data published in the domain. Since the global data space can be fully distributed, the system can scale without a single point of failure. In addition, the domain is a virtual data space in which DDS client applications send and receive data. Domain supports communication between domain participants, which encapsulates all data and communications from other domains in the domain. In addition, the DDS specification also defines six main entities, namely Domain Participant, DataWriter, Publisher, Subscriber, DataReader, and Topic. These entities cooperate with each other to complete the publish–subscribe process. In addition, the DDS DCPS specification also defines the QoS policy. This policy represents the minimum service level required for communication between DCPS entities, and the constraints of data communication between DCPS entities, so as to meet the different requirements of users for data sharing methods, such as reliability, fault handling, etc. [35].

4. DDS Protocol Modeling

When creating complex Petri nets, it is cumbersome to create CPN models with traditional methods. Therefore, the first step in the modeling process is to adopt the modularity idea, which means dividing the whole process into different levels. A simplified network model at the highest level is established in a broad sense, and then the subpages are refined by using the alternative transition at the higher level.

4.1. System Initialization

In the initialization phase, the certificate is generated by the Certificate Authority (CA), and the identity of the participant is verified according to the certificate. Additionally, the CA is responsible for generating an asymmetric key pair, public key and private key, for each certificate. After confirming the identities of both participants, the identity information of the participants is read from the digital certificate. Only through CA certification can the CA issue certificates to both participants. Afterwards, a shared key is generated. The establishment of the shared key in the protocol adopts the Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH) key agreement method. The specific scheme is as follows:

Each participant has a public–private key pair based on elliptic curves, and establishes a shared key through an insecure channel. Suppose M wants to establish a shared secret with S, but the channel available to them is not secure. Initially, the domain parameter (p, a, b, G, n, h) must be agreed upon. Additionally, each party must have a key pair suitable for elliptic curve cryptography, consisting of a private key d (d∈[1, n − 1]) and a public key Q, where Q = dG. M’s private key and public key are (SKm, PKm), S’s key pair is (SKs, PKs). M computes SKmPKs to generate a shared key, due to the unequal status of the communication parties in the original scheme of the DDS protocol, that is, the shared key is only generated by the communication party M, so the other party S just passively accepts.

4.2. DDS Protocol Message Flow Model

In DDS security, the identity authentication process is split into two parts: the local participant authentication process and the mutual authentication and key negotiation process between the local participant and the remote participant, this paper only studies the latter. There is no client side or server side in the mutual authentication and key negotiation process between the local participant and the remote participant because it is a Peer to Peer (P2P) protocol, and the status of both sides in the authentication process is equal [13]. The DDS security specification stipulates that before authenticating the identity of the participant, the participant must first be configured with a certificate and private key through a shared CA, and the CA must be safe and reliable. The descriptions of the required symbols are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Symbols and descriptions.

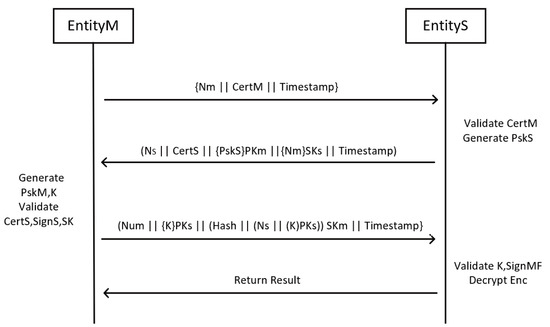

Figure 4 shows the transmission process of its information:

Figure 4.

Message flow model of DDS protocol.

Step 1: Participant M first sends its own certificate CertM and a random number Nm to participant S, and S verifies the validity of the certificate after receiving the message from M;

Step 2: After verifying that the certificate information is legal, S sends its own random number Ns and its own certificate CertS to M, and signs the random number Ns with the private key. M verifies the validity of the certificate and signature after receiving the message from S;

Step 3: After verifying the validity of the message, M sends information to S, uses the public key to encrypt the shared key K and the message signature, uses the hash function to calculate the random number Ns and encrypted information, and then uses the private key to sign. The role of the shared key K is to determine whether the identity of the other party is legal by judging whether the other party has the same key. After receiving the information from M, S verifies the validity of the message, thereby completing the identity authentication.

4.3. Formal Modeling Process

The CPN model describes a pair of communicating entities: a sender and a receiver. The two communication entities are connected by a network channel, which represents a communication channel. The static characteristics of the model, such as state, are represented by the distribution of tokens, and the dynamic characteristics, such as state changes, are described by transition enabling rules and the flow of tokens. Combined with the definition of CPN, taking the first message MSG1 as an example, the DDS protocol is formally defined as the following nine-tuple: DDS = (Σ, P, T, A, N, C, G, E, I):

Color set Σ = colset NONCE = with Nm|Ns; colset CertM = STRING;

Place set P = Nm, CertM, Msg1, S1;

Transition set T = NmCertM, msg1;

Directed arc set A = Nm→NmCertM; CertM→NmCertM; NmCertM→Msg1; Msg1→msg1; msg1→S1;

Node function N = Nm→NmCertM: (Nm,NmCertM); CertM→NmCertM: (CertM,NmCertM); NmCertM→Msg1: (NmCertM,Msg1); Msg1→msg1: (Msg1,msg1); msg1→S1: (msg1,S1);

Color function C= Nm:NONCE; CertM:CertM; Msg1:MSG1; S1:MSG1;

Alert function G = ϕ;

Arc expression function E = Nm→NmCertM:Nm; CertM→ NmCertM:certm; NmCertM→ Msg1:Nm,certm; Msg1→msg1:msg1; msg1→S1:msg1;

Initialization function I = Nm:Nm; CertM:CertM; Msg1,S1:NULL.

4.4. Related Color Set Definitions for Protocol Models

Due to the variety of message types generated by the protocol during the interaction process, it is necessary to use the advantages of the CPN Tools color set expression to define the data type before modeling, so that the modeling can proceed smoothly. Key color set definitions are shown in Table 3:

Table 3.

Model’s color set definition.

4.5. CPN Modeling for DDS Protocol

In order to precisely represent the network communication process and to reduce the model’s complexity, the protocol model is condensed into three layers: top, middle, and bottom. A detailed description of the message flow follows the subdividing of each layer, then subdividing each layer leads to a detailed analysis of the protocol’s message flow.

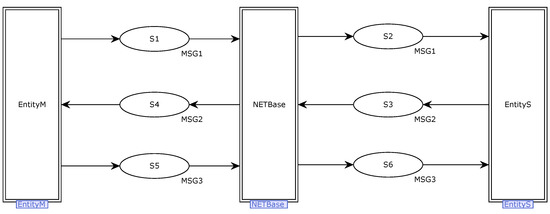

Figure 5 displays the top-level CPN model of the DDS protocol. A top-level model simulates the interaction between protocols in a broad sense, including both parties involved in the protocol, network channels, and transmission information.

Figure 5.

A top-level model for the DDS protocol.

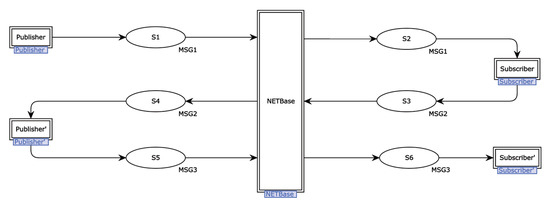

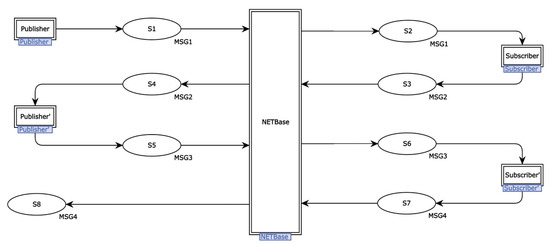

Figure 6 illustrates the mid-level protocol design, which has five alternative transitions and six places. When the two parties establish interaction, the alternative transition Publisher on the left describes the process of participant M establishing connection information to participant S, and the alternative transition Publisher’ describes the process of M processing and replying to the connection information. The middle NETBase describes the communication process of the transmitted information in the network channel. The alternative transition Subscriber on the right describes the process of S processing and replying to the connection information. Substitute transition Subscriber’ describes the process of S’s processing and comparison of security data.

Figure 6.

The mid-level model of the DDS protocol.

The alternative transition NETBase is illustrated in Figure 7. In the process of establishing a channel for the transmission of publish-subscribe messages, the transition Mes1, Mes2, and Mes3 imitate the process of initiating an authenticated message from M to S and the authentication of the message delivered by S to M, respectively.

Figure 7.

Alternative transition NETBase’s internal model.

The alternative transition Publisher is illustrated in Figure 8. Through the place of Msg1, the transition of NmCertM is assembled into an information packet and sent to the network channel.

Figure 8.

Publisher internal model for alternative transition.

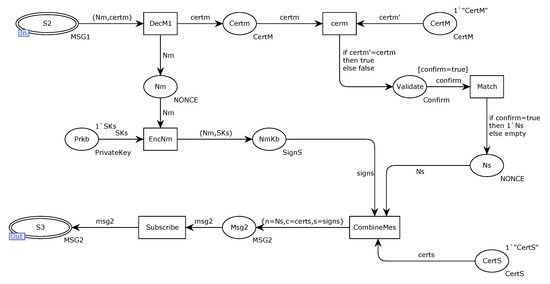

The alternative transition Subscriber is illustrated in Figure 9. After the data are successfully received, the validity of the certificate is verified through the Validate of the place. After the verification is successful, the message is synthesized through the transition of CombineMes, and the message is sent to the network channel through Msg2.

Figure 9.

Subscriber internal model for alternative transition.

The alternative transition Publisher’ is illustrated in Figure 10. After successfully receiving the data, decompose the message through the transition of DecM2, get the atomic message and verify the legitimacy of the message through Validate of the place. If the verification is successful, the message is synthesized through the transition EnchKa, and the message is sent to the network channel through Msg3.

Figure 10.

Publisher’ internal model for alternative transition.

The alternative transition Subscriber’ is illustrated in Figure 11. After successfully receiving the data, it decomposes the message through the transition decM3, and the place HkA synthesizes the message to verify the legitimacy of signmf. A message of execution success is returned if it is the same; otherwise, the message is reset.

Figure 11.

Subscriber’ internal model for alternative transition.

4.6. Original Model Functional Consistency Verification

When the original model is analyzed in state space [36] using CPN Tools, a state space report is generated based on the running state of the model, which visually reflects the running state of the whole model. First, protocol outcomes are typically predicted against protocol criteria before the analysis is performed. We expect only one dead node and no loops in the model. Second, we compare the state space report to determine whether the protocol runs according to the protocol specification. We give the expected results of the model built, which will successfully implement a session connection and secure data transfer without a reset operation throughout the interaction. Based on the data in Table 4, it can be concluded that the number of state space nodes is the same as the number of strongly connected nodes, and the number of state space arcs is the same as the number of strongly connected arcs, indicating that there is no loop in the proposed model. The dead node is 1, indicating that all requests are executed, which is consistent with the expected result.

Table 4.

DDS protocol original model state space report.

5. Attacker Model Security Assessment

In 1983, Dolev and Yao published an important paper in the history of security protocol development. In this paper, Dolev and Yao proposed to distinguish the security protocol itself from the cryptographic algorithm specifically adopted by the security protocol, and to analyze the correctness, security, and redundancy of the security protocol itself on the basis of assuming a perfect cryptographic system [37]. Due to the high real-time nature of the DDS protocol, this paper attempts to introduce an attack model to the network channel.

5.1. Introducing the Attacker Model

In the Dolev–Yao attacker model, the attacker can control the entire network. The attacker behavior is as follows:

- The attacker can eavesdrop and intercept all messages passing through the network;

- The attacker can store or send intercepted or self-constructed messages;

- The attacker can participate in the operation of the protocol as a legitimate subject.

As shown in Figure 12, we add a man-in-the-middle attack to the network channel. A replay attack is simulated by the places and transitions highlighted in red in the figure. When a protocol transmits data for the first time, the transition T0 intercepts it and stores it in the P1 of the place, the decomposed data is stored in Place Q1 and Q2, the place P2 stores information that cannot be decrypted from the transition T2, this procedure adopts the strict rules of the attacker. The attacking information finally sent by the attacker to the channel port place is synthesized through the transition T4. The arc expressions marked in purple in the figure and the transition repository simulate the tampering attack, and the attack is launched through the transition Attack. The blue part in the figure simulate the spoofing attacks, including transition Mes1, transition Mes2, and transition Mes3.

Figure 12.

Attacker model.

5.2. DDS Model Security Assessment

From the state space report of the attacker-based model shown in Table 5. Among them, REY-ATK represents the replay attack model, TAR-ATK represents the tampering attack model, and SPF-ATK represents the spoofing attack model. As can be seen, the number of state space nodes, state space arcs, and strongly connected nodes, as well as strongly connected arcs are consistent, indicating that there are no loops in the model, which is in accordance with the modeling expectations. At the same time, the number of dead nodes changes from 1 to 6. By writing ML and using the ListDeadMarkings () function, the serial numbers of all dead nodes can be determined, we can find that two dead markings are generated due to the introduction of tampering attacks resulting in the reset operation of the message from the participant, and the other two dead markings are replay attacks caused by attackers stealing legitimate messages and faking them to prevent legitimate messages from the participant. The number of spoofing attacks is 1, indicating that the protocol is completed, and there is no spoofing attack in the protocol, which is in line with the actual situation of the protocol. At the same time, use the NodeDescriptor() function to print the 10,380 node data, the data indicate that the state is the protocol termination state, indicating that the identity authentication is over, as shown in Figure 13. By comparing and analyzing the original model with the attack model, it is demonstrated that this attack model can effectively attack the connection and transmission processes of the original request commands, the original protocol has vulnerabilities that could be exploited by a man-in-the-middle attack, including replay and tampering.

Table 5.

Original and attacker state space reports.

Figure 13.

Identity authentication result.

6. New Scheme of DDS Protocol

By introducing attackers to conduct security assessment of the protocol, it is found that there are security vulnerabilities in the protocol for tampering and replay attack. In order to ensure fairness and security, the establishment of the shared key must be jointly participated in by both parties. However, in the original scheme, the positions of the two communicating parties are not equal, that is, the shared key is only generated by the communicating party M, and the other party S is only passively accepted, and does not play its due role in the key-establishment process. At this time, if the attacker has intercepted the shared key, S will not be able to determine whether the shared key is safe. If the key is still used to derive other related keys or perform encryption and decryption, the attacker will obtain the content of the message, resulting in information leakage. In addition, the original protocol lacks an effective method to verify key consistency, so all information generated using this shared key cannot guarantee confidentiality and security.

In response to the security assessment results, we introduce timestamps into the original protocol and set time thresholds to ensure that data is securely verified. In addition, due to the lack of message integrity, consistency and fairness in the original protocol, the two communicating parties cannot determine whether the other party receives the key message safely. Therefore, we changed the method of generating the shared key in the original protocol, increased the key verification process and added a counter to achieve session integrity.

6.1. Scheme for Protocol New Reinforcement

As shown in Figure 14, the improved message flow diagram is as follows:

Figure 14.

Model of the new scheme message flow.

Step 1: Participant M sends its own certificate CertM, a random number Nm and a timestamp to participant S. S verifies the validity of the certificate after receiving the request message from M;

Step 2: After S verifies that the certificate information is legal, S sends its own random number Ns and its own certificate CertS to M, and signs the random number Ns with the private key; at the same time, it generates a pre-shared secret key and encrypts it with the public key. After M receives the message from S, it verifies the validity of the certificate and signature information;

Step 3: M decrypts the received message and generates a pre-shared key and compares it with the pre-shared key generated in the previous step. If it is not equal, it indicates that it is safe and combines to generate a shared key K. The message includes public key encryption shared key K, signature information, a counter Num and a timestamp information. After receiving the information from M, S verifies the validity of the message. If the message is valid, reply to the message; otherwise, end the communication.

Step 4: M receives the message from S and verifies whether the shared key K is the same. If K is the same, it means that the message is legal, and the counter is incremented by 1 to complete the identity authentication process.

6.2. New Scheme Model of DDS Protocol

On the basis of the original protocol, we reinforce it and make improvements to the protocol itself. To enhance protocol security, a new security mechanism is added during data transfer.

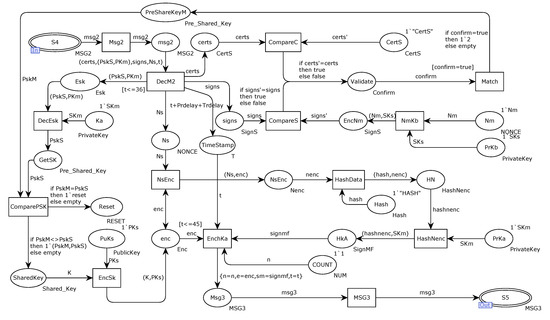

Aiming at the discovered protocol security loopholes, CPN modeling verification is carried out based on the new scheme, which enhances the original protocol. As shown in Figure 15, the new scheme has four alternative transitions and eight places in the middle layer. In the new scheme, the middle layer describes the connection process, as well as the transmission process of reply information.

Figure 15.

The mid-level model of the new scheme of DDS protocol.

Figure 16 depicts in detail the Publisher model for the alternative transition. Timestamps are introduced into the original message. The transition NmCertM is combined into an information packet and the information is sent to the network channel through the place InitMes.

Figure 16.

The new scheme replaces the internal model of the transition Publisher.

Figure 17 depicts in detail the Subscriber model for the alternative transition. After the data are successfully received, the validity of the message is verified through the Validate of the place. After the verification is successful, S generate a pre-shared secret key and encrypt it with M’s public key, adding a timestamp to the original message, the message is synthesized through CombinMes, and the message is sent to the network channel through Msg2.

Figure 17.

The new scheme replaces the internal model of the transition Subscriber.

Figure 18 depicts in detail the Publisher’ model for the alternative transition. After the data are successfully received, the message is decomposed by DecM2, and the validity of the message is verified by the Validate of the place. After the verification is passed, a pre-shared secret key is generated and compared with the decrypted message. If they are not equal, combine them to generate the shared secret. At the same time, the counter Num and timestamp are added in the message transmission process, the message is synthesized by the transition of EnchKa, and the message is sent to the network channel through Msg3.

Figure 18.

The new scheme replaces the transition Publisher’s internal model.

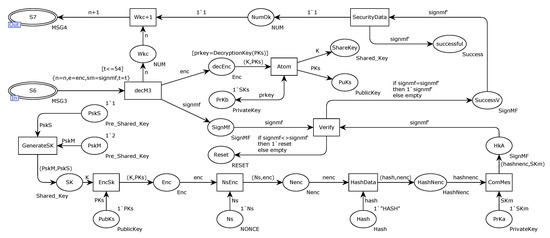

Figure 19 depicts in detail the Subscriber’ model for the alternative transition. After the data are successfully received, the message is decomposed by decM3. Compare the generated shared secret, if the verification fails, the message is reset; if the verification passes, the counter is incremented by 1, and returned through the transition Wkc+1. M confirms that S has received the shared key securely, ensuring the integrity of the session.

Figure 19.

The new scheme replaces the transition Subscriber’s internal model.

6.3. Model Validation

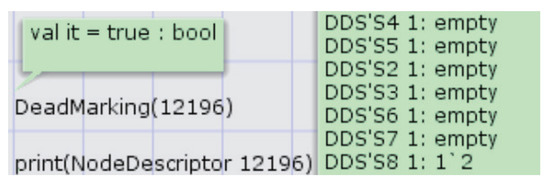

CPN model verification is to describe the nature of the system by introducing the ASK-CTL branch temporal logic formula. If the property is satisfied, the return value is true, otherwise the return value is false. We defined a state formula of ASK-CTL, the name of the formula is myASKCTLformula, which means to verify whether the place S8 in the NETBase page is in the normal termination state, that is, the state node is a dead identification node or a normal termination node. As shown in Figure 20, the result returns true, indicating that the verification result is consistent with expectations and the model is correct.

Figure 20.

ASK-CTL formula and its verification results.

6.4. New Scheme Security Assessment Model

Considering the operation delay of the transition in the model and the maximum time for the normal transmission of the message, we add a timestamp on the basis of the original protocol. We use the same approach and introduce the Dolev–Yao attack model to perform a man-in-the-middle attack on the network level of the new scheme model, as shown in Figure 21. A replay attack is simulated by the red part, a tampering attack by the purple part, and a spoofing attack by the blue part.

Figure 21.

Attacker model for the new scheme.

6.5. New Scheme Model Security Verification

The security evaluation of the new scheme model is compared with the one prior to the improvement. Table 6 presents the state space data of the three attack models before and after improvement. We can find that the number of nodes increases due to the timestamp and verification key consistency steps introduced in the data transfer process. From the table, we can see that the dead node of REY-ATK has been reduced from 2 to 1. By writing a query function to query 12,196 nodes, it shows that this is the termination state of the protocol, which is in line with the expected result. Among them, DeadMarking() is used to judge whether the mark of the specified node is dead, that is, whether there is an enabled binding element. If it returns true, there are no enabled binding elements, which is the protocol termination state. NodeDescriptor() is used to print the actual state of the node, it can be seen that the Num in S8 is increased by 1, indicating that the protocol operation is completed, as shown in Figure 22.

Table 6.

State space comparison under three attack models.

Figure 22.

Protocol termination status query under replay attack.

Compared to the replay attack against the previous protocol, it can be seen that the probability of replay attack is reduced by about 8%. At the same time, the introduction of the new security mechanism increases the protocol processing process. By comparing the number of steps, we see 5% of increase in processing step. The addition of timestamps ensures the freshness of messages and resists replay attack. New security measures appear to act as an effective deterrent against the aforementioned man-in-the-middle replay attack and enhanced the overall security of the protocol. By comparing the dead nodes before and after the improvement of the protocol, it is calculated that the overall security performance of the improved protocol has increased by about 16.7%.

6.6. Safety Assessment

As shown in Table 7, by comparing the state space analysis results before the improvement, it can be seen that the number of nodes and arcs in the improved state space increases significantly, this is because we add timestamps and verification steps, and the number of dead nodes reduced from 6 to 4. This shows that the improved hardening scheme is effective and can well resist replay attack.

Table 7.

State space comparison between the original attacker model and the new scheme attacker model.

6.7. Performance Analysis and Methods Comparison for New Scheme

This section makes a comparative analysis of the improved new schemes of DDS protocol. In practical application scenarios, protocol security is particularly important. By adding a new security mechanism, the security of the protocol is improved. At the same time, when the timestamp is added in the new protocol improvement scheme, the calculation and communication will increase, and the delay of the new scheme will increase slightly compared with the original scheme. According to the improved protocol operation, we define the time spent on encryption and decryption in the protocol process as Ten and Tde, and the time spent generating data as Tge, the time required for verification and hash function calculation is Tv and Th, respectively. The time required for Entity M is: 3Ten + Th + 3Tv + 2Tge; the time required for Entity S is: 2Ten + Tde + 3Tv + Tge; and the total time spent is: 5Ten + Tde + 6Tv + 3Tge + Th. There is not much impact on the performance of the original protocol.

We compared the formal analysis method used in this paper with other methods. Ref. [15] focuses on client-side attacks, models and demonstrates five attacks in independent and isolated environments, these security issues can be used as an attack method against dds based systems; Ref. [18] proposes an ABAC-based DDS security model authorization improvement method, and incorporates the ABAC entity into the security model that defines ABAC behavior across RTPS and DCPS, and implements the model in XACML; Ref. [38] proposes an attacker model that leverages network reconnaissance provided by leaky context, combined with formal verification and model checking to arbitrarily infer the underlying topology and reachability of information flows, enabling targeted attacks, such as selective denial of service, adversarial partitioning of the data bus, or exploiting of vendor-implemented vulnerabilities. Through the comparative analysis in Table 8, the scheme proposed in this paper can not only provide an intuitive and accurate graphical description and verify the correctness of protocol functions, but also discover the attack types of the protocol. At the same time, the scheme improves the introduced attack model and solves the problem of state space explosion in traditional model checking methods, this analysis scheme can be used to conduct security analysis and research on other protocols.

Table 8.

Scheme comparison analysis.

7. Discussion

This paper mainly uses the method of formalization of the protocol, combined with CPN Tools to formally analyze the DDS protocol and carry out security reinforcement for the protocol loopholes. In our improved scheme, we added timestamps to resist replay attack, because the DDS protocol has no limit on the packet size, so adding timestamps does not affect the network packet structure. According to the DDS-RTPS protocol, the minimum overhead for sending application data over the wire is 48 bytes. The overall structure of the RTPS message consists of a fixed-size RTPS header and a variable number of RTPS sub-messages, where the size of the RTPS header is 20 bytes. The reason why the RTPS sub-message changes is that, usually, multiple DATA can be put into the same RTPS message. In this case, the RTPS header and INFO_TS are shared, and INFO_TS is usually 12 bytes. When multiple DATA are put into the same RTPS message, the extra overhead is 28 bytes per message, and there is a batching feature, configurable in Connext DDS, which combines multiple payloads in the same data message. Using this feature, the overhead can be as low as 8 bytes per data message. For an RTPS message, the UDP message is actually a fixed byte length of 8 bytes. In order to prevent exceeding the minimum overhead, the timestamp size is defined as 8 bytes. In addition, since CAN open environment (CANoe) does not support the simulation function of DDS nodes for the time being, in the future we will consider simulating the DDS protocol based on the Security Management function of the CANoe platform [39].

8. Conclusions

In this paper, the security of the DDS protocol is mainly discussed. In order to evaluate and improve the security of the protocol, we adopt a model checking method combining the Dolev–Yao attack model and CPN theory. First, the protocol is originally modeled and validated using the CPN Tools modeling tool and CPN theory; second, in order to evaluate the security of the original model, the Dolev–Yao attacker model was introduced; finally, a new approach to deal with the security flaws in the protocol is proposed. Security verification should be performed using CPN Tools after the original protocol has been improved, it is shown that the improved scheme effectively resists man-in-the-middle replay attack and increases protocol security. In addition, CPN Tools can introduce ASK-CTL temporal logic formulas to describe the nature of the system, use rigorous mathematical theory to analyze the correctness of the model, and the verification results show that the model meets the expected design requirements. However, during the research process for this paper, a man-in-the-middle attack on the network channel is the only attack that is considered in this paper, as other attacks on the protocol are not considered. With the advent of Industry 4.0 and the new popularity of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), the DDS protocol in the automotive field will have large-scale applications with its advantages [40]. In the future, it can be considered to be applied in the wireless network environment on the premise of achieving industrial real-time performance and accuracy. The next step will consider the secure storage of the private key within the protocol and the security of the protocol under other forms of attack.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D., C.G., and T.F.; methodology, J.D.; software, C.G.; validation, J.D., C.G., and T.F.; formal analysis, J.D. and C.G.; investigation, J.D., C.G., and T.F.; resources, J.D.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D. and C.G.; visualization, J.D. and C.G.; supervision, T.F.; project administration, J.D.; funding acquisition, J.D. and T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62162039, 61762060) and the Foundation for the Key Research and Development Program of Gansu Province, China (Grant No.20YF3GA016), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Gansu Province, China (Grant No. 20JR10RA185).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used to support this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all editors and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions and all funding for the great help and support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DDS | Data Distribution Service |

| CPN | Colored Petri Net |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AMQP | Advanced Message Queuing Protocol |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| ML | Markup Language |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| TCPN | Timed Colored Petri Nets |

| HCPN | Hierarchical Colored Petri Nets |

| OMG | Object Management Group |

| SOME/IP | Scalable service-Oriented MiddlewarE over IP |

| DDSI | DDS Interoperability Wire Protocol |

| DCPS | Data-Centric Publish–Subscribe |

| DLRL | Data Local Reconstruction Layer |

| CA | Certificate Authority |

| ECDH | Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman |

| P2P | Peer to Peer |

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

References

- Nebbione, G.; Calzarossa, M.C. Security of IoT application layer protocols: Challenges and findings. Future Internet 2020, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassein, M.B.; Shatnawi, M.Q. Application layer protocols for the Internet of Things: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering and MIS (ICEMIS), Agadir, Morocco, 22–24 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, R.; Yousuf, T.; Aloul, F. Internet of things (IoT) security: Current status, challenges and prospective measures. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST), London, UK, 14–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seleznev, S.; Yakovlev, V. Industrial Application Architecture IoT and protocols AMQP, MQTT, JMS, REST, CoAP, XMPP, DDS. Int. J. Open Inf. Technol. 2019, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aures, G.; Lübben, C. DDS vs. MQTT vs. VSL for IoT. Network 2019, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, R.M.; Schroeder, M.D. Using encryption for authentication in large networks of computers. Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzer, A.V.; Wells, L.; Lassen, H.M. CPN tools for editing, simulating, and analysing coloured Petri nets. In Application and Theory of Petri Nets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard, M.; Kristensen, L.M. The access/cpn framework: A tool for interacting with the cpn tools simulator. In Conference on Application and Theory of Petri Nets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Feng, T.; Zheng, L. Formal Security Evaluation and Improvement of Wireless HART Protocol in Industrial Wireless Network. Secur. Commun. Net. 2021, 2021, 8090547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.W.; Gao, P.; Xu, X.Y. Design of dds secure communication middleware based on security negotiation. Netinfo Secur. 2021, 21, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, C.; Di, H.T.; Guo, Q.L. Research on identity authentication method for data distribution service. Electron. Technol. 2015, 44, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.J.; Ye, H.; Wang, L. Design of authentication protocol for high-security data distribution service. Aeronaut. Comput. Tech. 2015, 45, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, K.; Reininger, J. Adaptation of the DDS security standard for resource-constrained sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Industrial Embedded Systems (SIES), IEEE, Graz, Austria, 6–8 June 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, M.J.; Dean, T.; Leblanc, S.P. Attacking omg data distribution service (dds) based real-time mission critical distributed systems. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE), Nantucket, MA, USA, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, M.J.; Leblanc, S.P. Vulnerability Analysis of the OMG Data Distribution Service (DDS). Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Military College of Canada Computer Security Laboratory, Kingston, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ioana, A.; Korodi, A.; Silea, I. Automotive IoT Ethernet-based communication technologies applied in a V2X context via a multi-protocol gateway. Sensors 2022, 22, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, D.K.; Alaerjan, A. ABAC-based security model for DDS. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 19, 3113–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Formal Security Assessment and Improvement of DNP3-SA Protocol Based on HCPN Model Detection. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Xu, L.; Li, X. A lightweight and provably secure key agreement system for a smart grid with elliptic curve cryptography. IEEE Syst. J. 2018, 13, 2830–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, Z. Cryptanalysis and improvement of the YAK protocol with formal security proof and security verification via Scyther. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2020, 33, e4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, C.; Dehnel-Wild, M. Component-based formal analysis of 5G-AKA: Channel assumptions and session confusion. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS) 2019, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–27 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada, H. Security Evaluation of the PLAID Protocol Using the ProVerif Tool. 2013. Available online: http://crypto-protocol.nict.go.jp/data/eng/ISOIEC_Protocols/25185-1/25185-1_ProVerif.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2013).

- Feng, T.; Jiang, X.Y.; Fang, J.L.; Gong, X. A New Scheme of BACnet Protocol Based on HCPN Security Evaluation Method. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2022, 24, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, D.; Criscione, F.; Trapani, N. Risk assessment in a chemical plant with a CPN-HAZOP Tool. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artamonov, I.V.; Sukhodolov, A.P. CPN Tools-based Software Solution for Reliability Analysis of Processes in Microservice Environments. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2018, 19, 56.1–56.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Object Management Group: Data Distribution Service(DDS). Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Cao, W.H.; Me, B.; Wu, H.X. Design of publish/subscribe middleware based on dds. Jisuanji Gongcheng/Comput. Eng. 2007, 33, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Object Management Group: DDS Security (2021). Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/1.0/ (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- Object Management Group: DDS Security (2021). Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/1.1 (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Van’t Hag, J.H. Data-Centric to the Max—The SPLICE Architecture Experience. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops, Providence, RI, USA, 19–22 May 2003; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Sandström, K.; Nolte, T. Data distribution service for industrial automation. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA 2012), Krakow, Poland, 17–21 September 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Balador, A.; Ericsson, N.; Bakhshi, Z. Communication middleware technologies for industrial distributed control systems: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Limassol, Cyprus, 12–15 September 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Schmidt, D.C.; van’t Hag, H. Toward an adaptive data distribution service for dynamic large-scale network-centric operation and warfare (NCOW) systems. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2008 IEEE Military Communications Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–19 November 2008; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Eryigit, C.; Uyar, S. Integrating agents into data-centric naval combat management systems. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Computer and Information Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey, 27–29 October 2008; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kontšek, M.; Segeč, P.; Moravčík, M. Approaches and tools for network protocol modeling. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 21–22 November 2019; pp. 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, V.; Talcott, C. Formal security verification of industry 4.0 applications. In Proceedings of the 24th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Zaragoza, Spain, 10–13 September 2019; pp. 1043–1050. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.; Caiazza, G.; Jiang, C. Network reconnaissance and vulnerability excavation of secure DDS systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops, Stockholm, Sweden, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Z.; Yang, S.; Ma, B. Design of a CANFD to SOME/IP Gateway Considering Security for In-Vehicle Networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Sandhu, R. Authorization framework for secure cloud assisted connected cars and vehicular internet of things. In Proceedings of the 23nd ACM on Symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 13–15 June 2018; pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).