Adaptive User Profiling in E-Commerce and Administration of Public Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

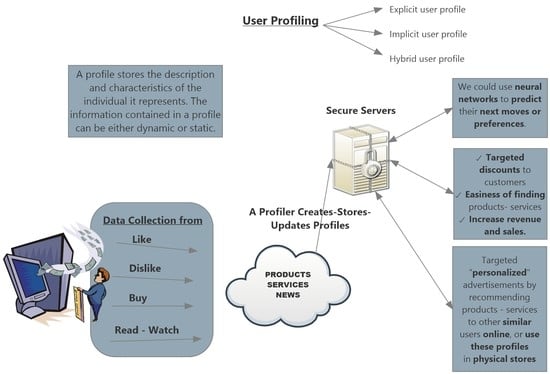

2.1. User Profiling

2.2. Profile Structure

2.2.1. Profile Monitoring

- -

- Direct monitoring of the use of the application by keeping a history of the usage pattern.

- -

- Storing the history by the system to avoid failures.

- -

- Immediate feedback on the performance of the service.

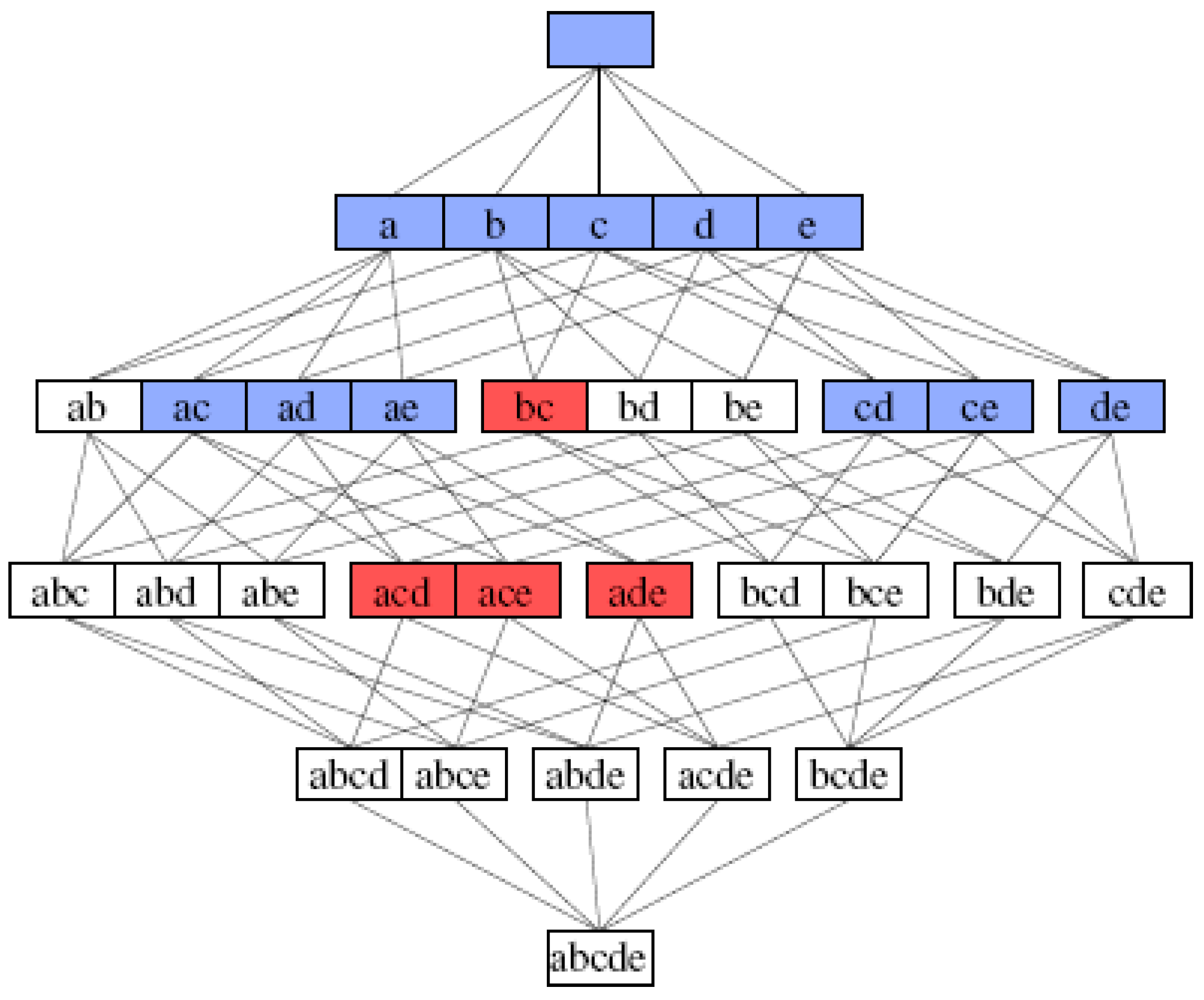

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Data Analysis

2.3. User Modeling

Types of Data in User Models

2.4. Uses of User Model Data

2.4.1. Experienced Systems

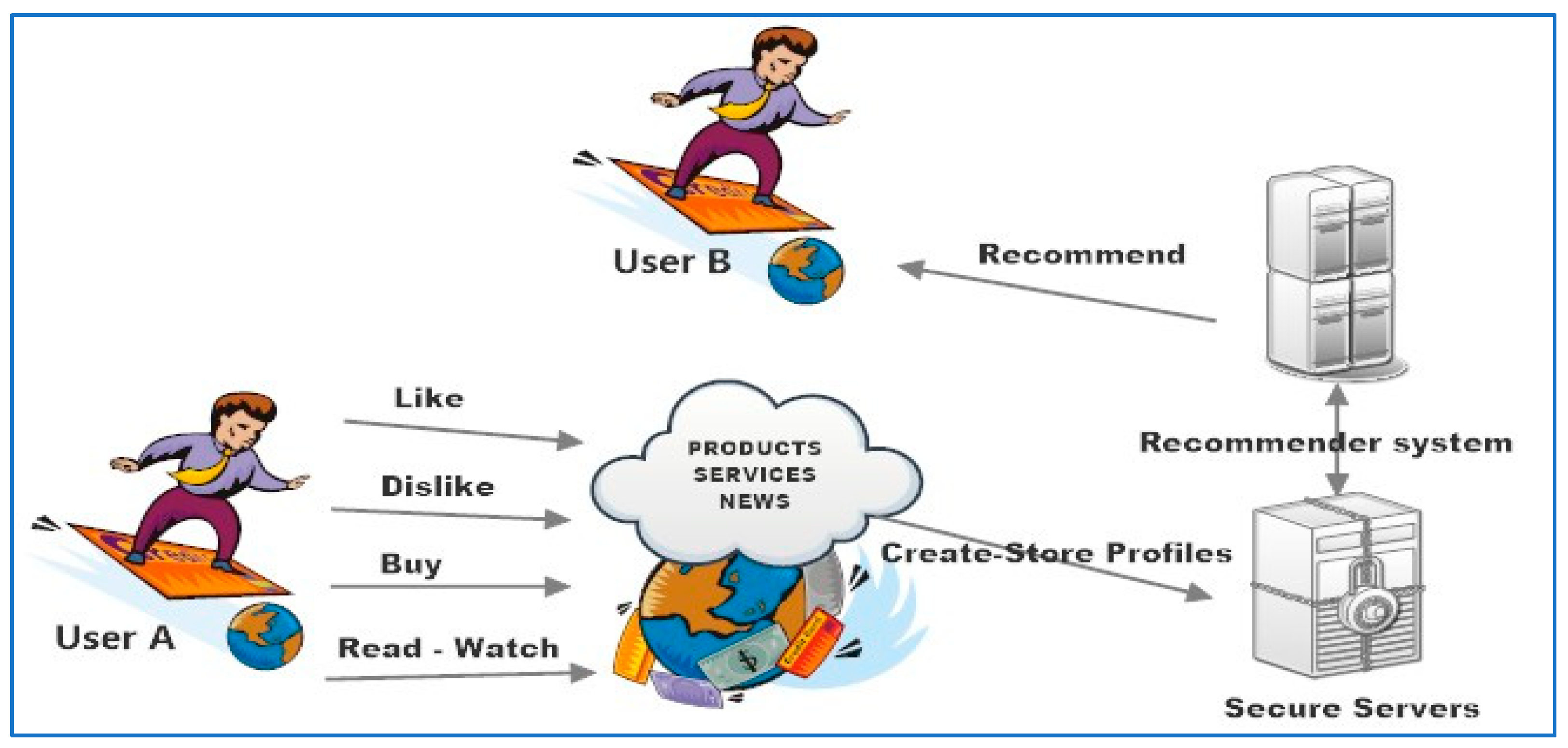

2.4.2. Recommendation Systems

2.4.3. User Simulation

2.5. Knowledge Extraction

2.6. Similar Systems

2.6.1. The WEST System

2.6.2. The Gumsaws System

2.6.3. The CATS System

2.6.4. The PCAHTRS System

2.6.5. The Hootle

3. Our Proposed Implementation

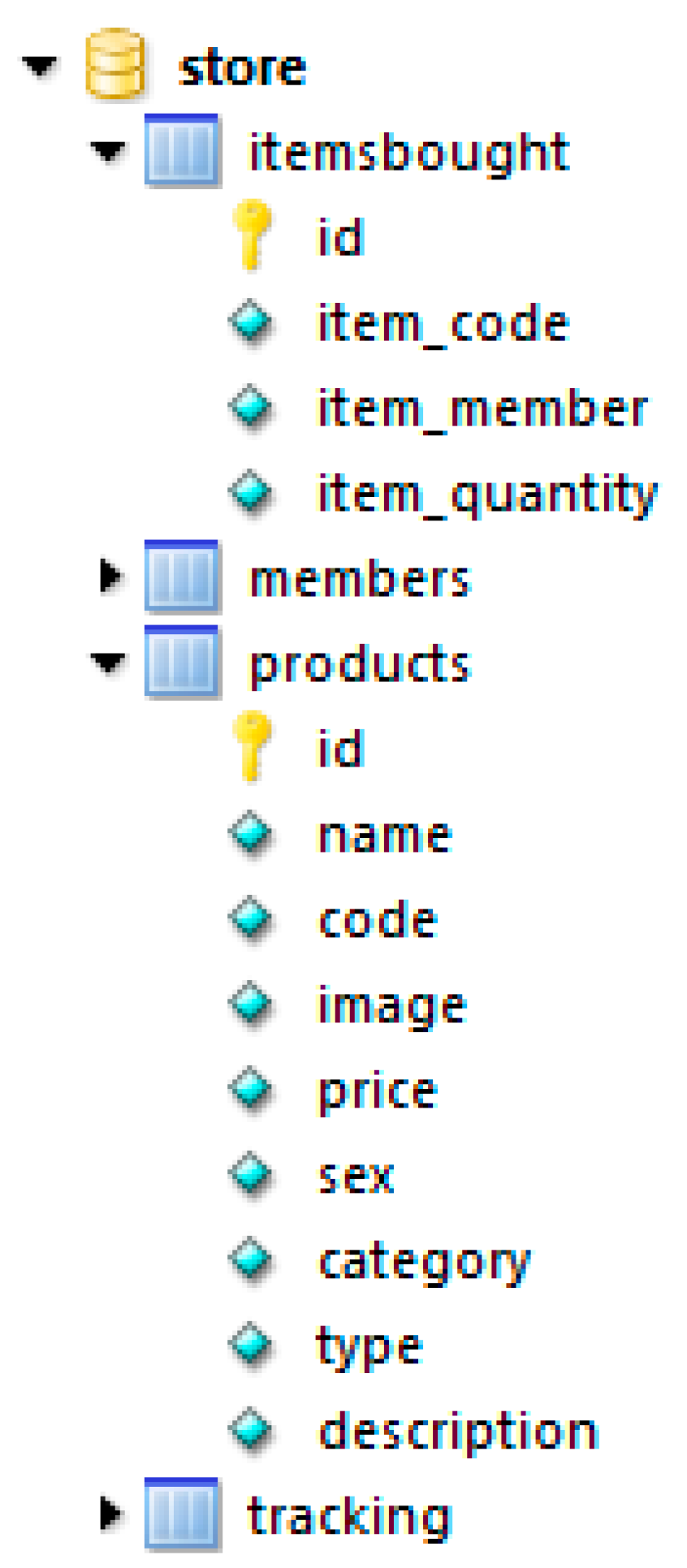

3.1. The Database

3.2. User Tracking Technique

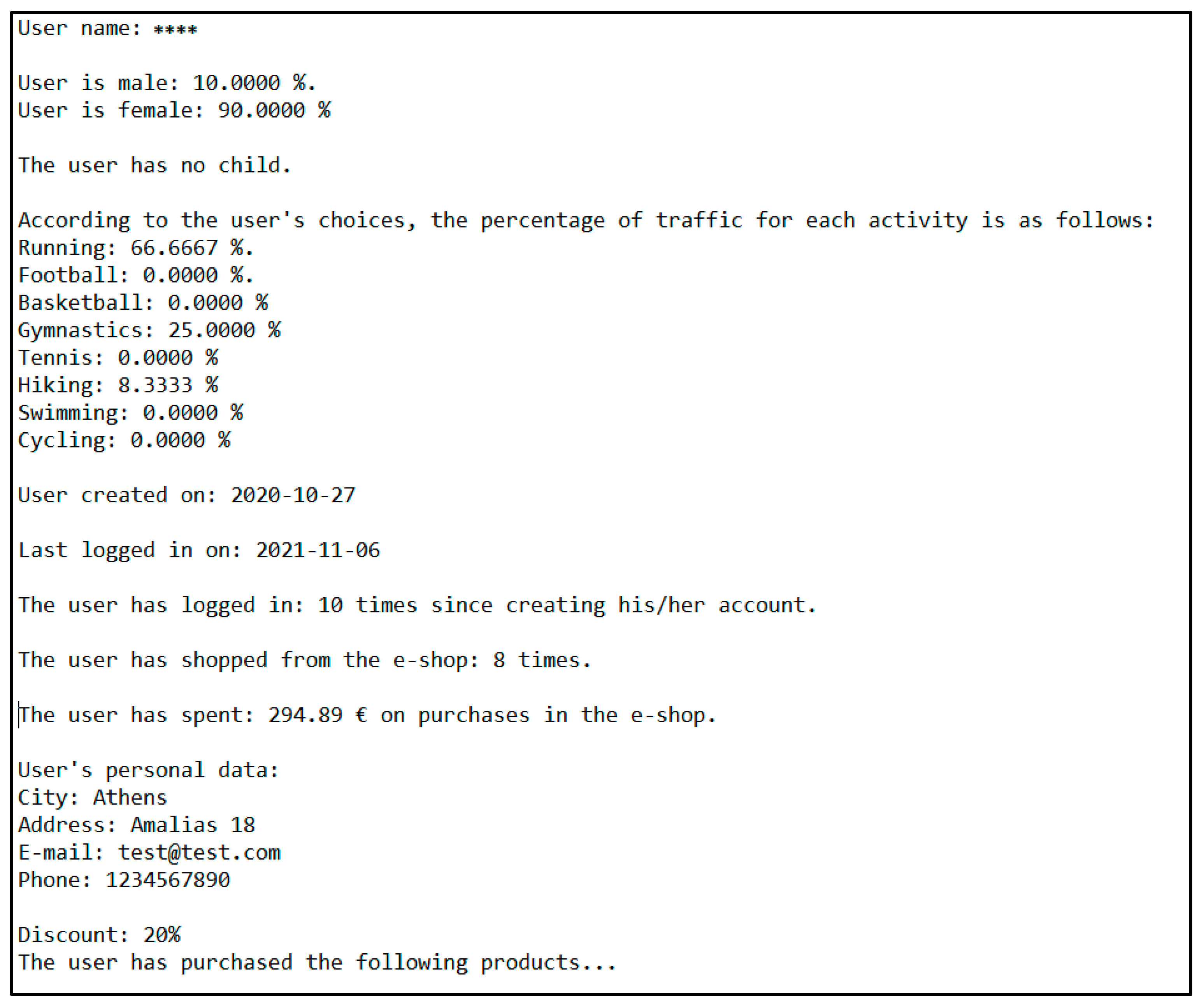

3.3. Data Analysis and Display Technique

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Testing of the Application with Real Users, Analysis of the Results through Questionnaires and SPSS

4.2. European Data Protection Regulation

- -

- Integrity: which refers to ensuring that the information that is handled, published, stored and processed remains unchanged.

- -

- Identification: which refers to the identification of the user’s identity;

- -

- Confidentiality: which refers to access to information only by those who have the appropriate authorization.

- -

- Authentication: refers to the specific action that ensures that the identity declared by the user actually corresponds to the user.

- -

- Authorization: which refers to ensuring that each entity has access to those system resources to which it has been granted access.

- -

- Availability: relating to the availability of information whenever an authorized user attempts to access it.

- -

- Non-repudiation: which refers to the inability of a user to deny that he/she has performed an action related to accessing, entering and processing information. The security of public websites consists of a complex set of guidelines and rules relating to the organization of the website operator and the hosting provider, the procedures it applies, the services it provides, the technical infrastructure at its disposal and, finally, the legal framework for the protection of personal data and the security of communications.

4.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

- -

- Hiking

- -

- Swimming

- -

- Running

- -

- Cycling

- -

- Football

- -

- Basketball

- -

- Gym

- -

- Tennis

- -

- Sex (Male or Female?)

- -

- Parent (Is this user a parent?)

- Question: Which username did you use when you registered?This question was asked to know exactly which username he/she used when he/she created the account in our system so that we can compare our findings for that specific user.

- Question: What is your gender?According to the replies to the questionnaires, 57 were males and 43 were females. Our online profiling system successfully predicted the gender for 84 of those users (47 males and 37 females). This means that the success rate of our system for the gender reached a percentage of 84%. In Table 2, the success rate of the gender prediction is presented.

- Question: Are you a parent?Of the participants, 32 replied that they were parents and 68 replied that they were not. Based on the findings of our system, it predicted the correct parenthood for 49 of those users. In Table 3, the success rate of the Parenthood prediction is presented.

- Question: What are your interests? Choose the ones that interest you (Running, Football, Basketball, Gymnastics, Tennis, Hiking, Swimming, Cycling)In this question, users had the choice to pick any activities that they really like. For each one of these activities and for every user, we analyzed the findings of our profiling system. It turned out that the system worked very well and made accurate predictions. In the following tables the success rates of each activity is presented.

- Question: Would you be comfortable if you knew that an online store records your movements on it, and “creates” your shopping profile, in order to offer you in the future better services and special individual offers for your needs? e.g., to offer you a big discount on certain products that it “knows” you like?Of the responders, 49% said that they would feel comfortable knowing that their movements are recorded in their online shopping profile and 37% replied that they maybe would be. This means that almost 85% of us are aware that all of our online transactions are recorded and stored in our profiles. It is very important for all this personal information to be used for the right purposes. Nonetheless, it is that risk of violation of the user’s privacy that made the remaining 15% feel uncomfortable about the exposure of their online profiles.

- Question: How much money per visit are you willing to spend on an online store per visit?Of the users that replied, 32% that they would spend more than 50 and less than 100 euro for their online purchases. Another 24% responded that they would spend more than 100 and less than 150 euro, and 23% responded that they would spend less than 50 euro. This means that online customers are afraid of spending a lot of money online to buy their goods. This is probably because they are afraid that their personal data and their credit card details will be exposed.

- Question: How often would you buy from an online store?In this case, 44% of the users replied that they often buy from online stores. Another 26% said very often, 28% not often and only 2% replied that they would never buy from an online store, which means that the majority of the people today are using the Internet to buy products.

- Question: Do you have any concerns when shopping online?In response to this question, 56% said no, and 44% said yes. If the risk of users’ privacy violation is reduced, then it is certain that more customers will be less concerned when shopping online.

- Question: How many times have you purchased products online in the last year?In response to this question, 37% replied that they’ve made fewer than 10 purchases over the last year, 31% more than 10 and fewer than 20 and 15% responded that they have bought more than 50 times online. These numbers are expected to increase, since we will all find relevant products at better prices through profiling systems.

- Question: Age in years?Among the users, 39% were in the 18–29 age group, 27% were between 30 and 39 years old, 16% were more than 40 and less than 50 and the rest were above 50. Younger people tend to use the Internet more often for all their transactions.

- Question: Educational Profile?Of the users, 26% were high school graduates, 27% were university graduates, 16% were graduates of TEI (Technological Educational Institute), 12% possessed a master’s degree and 9% were PhD graduates. The remaining 10% possessed lower levels of education, such as high school or primary school. The majority of our users were adequately educated.

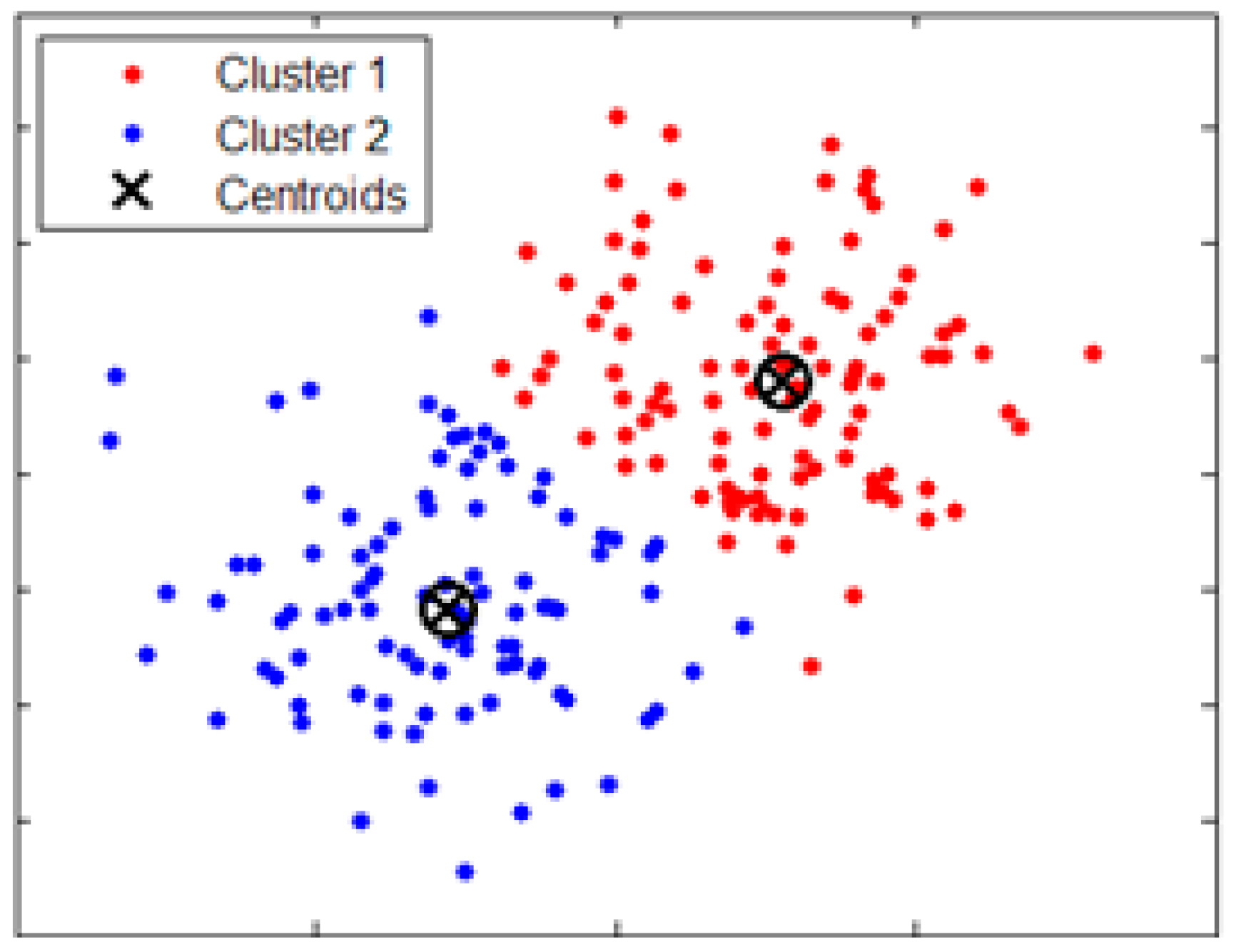

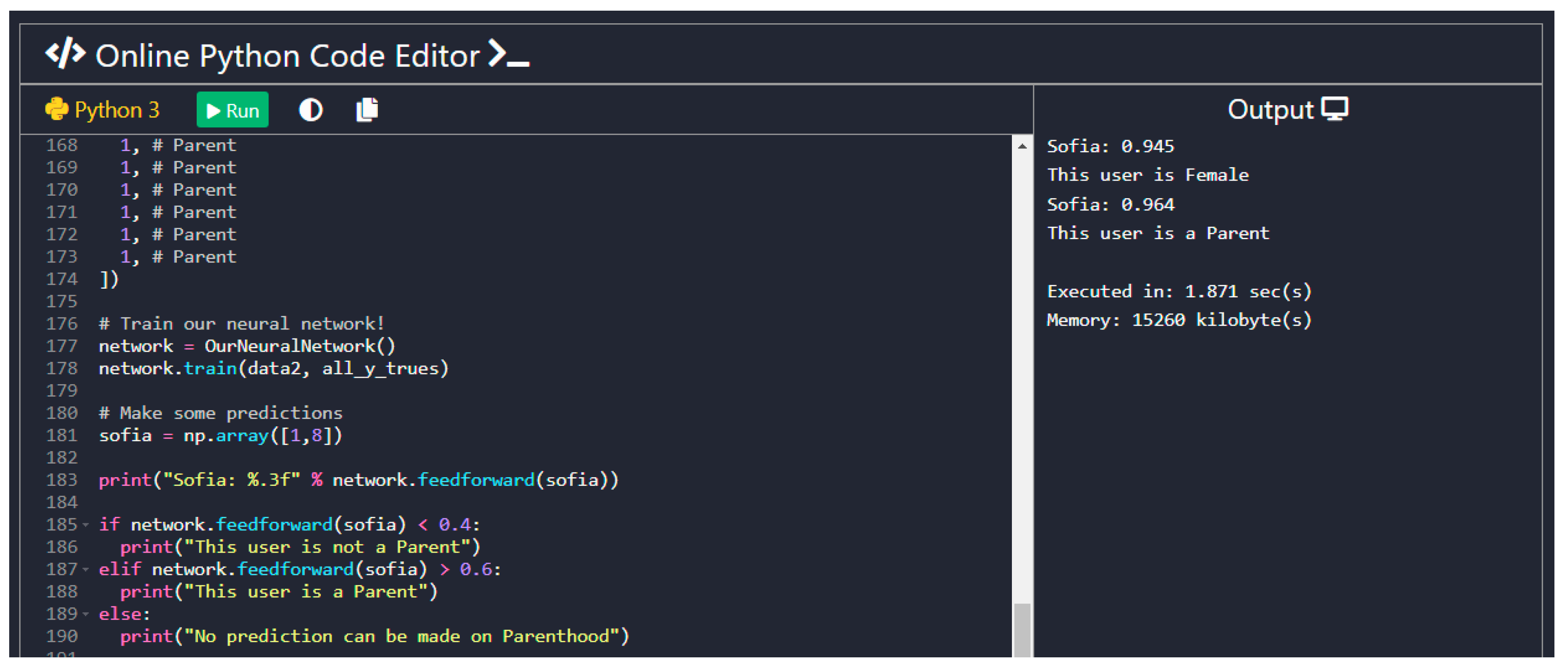

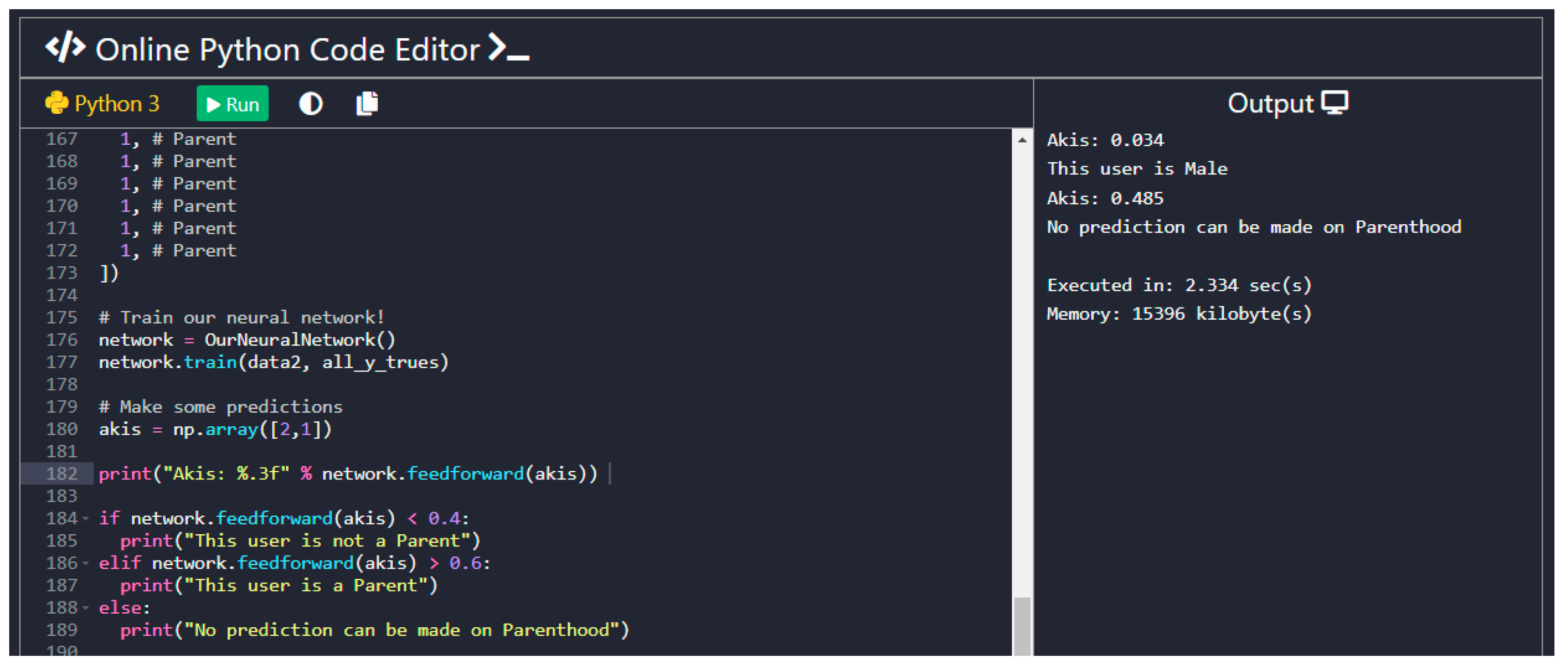

4.4. Use Neural Networks in Predictions of Our Users

4.4.1. Steps in Implementing a Neural Network

- Feed forward:

- Back propagation:

4.4.2. Why Is Back Propagation Needed?

4.4.3. Sigmoid Function

4.4.4. Coding and Training a Neural Network

- Determine how close the actual neuron is to the output of the network and compare it to the applicable output.

- Change the weights of each connection so that the network produces a better approximation of the desired output.

- To train a neural network to perform a specific function, it is necessary to adjust the weights of each unit to minimize the error between the expected output and the actual one.

4.4.5. Key Points of the Code and Screenshots of the Outcomes

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CATS | Collaborative Advisory Travel System |

| TEI | Technological Educational Institute |

| GRS | Group recommender system |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| ID | Identity document |

| PCAHTRS | Personalized Context-Aware Hybrid Travel Recommender System |

| PHP | Hypertext Preprocessor |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| PHD | Doctor of Philosophy |

References

- Wagh, R.; Patil, J. Enhanced web personalization for improved browsing experience. Adv. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2017, 10, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Abri, S.; Abri, R.; Cetin, S. A classification on different aspects of user modelling in personalized web search. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Information Retrieval, Seoul, Korea, 18–20 December 2020; pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaev, M.A.; Pogorelova, A.O. Profiling of Website Visitors Based on Dimensions of User Experience. In Proceedings of the 2021 XV International Scientific-Technical Conference on Actual Problems Of Electronic Instrument Engineering (APEIE), Berdsk, Russia, 19–21 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoje, S.; Girase, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. User Profiling for Recommendation System. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.06555. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoje, S.; Girase, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. User profiling trends, techniques and applications. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.07474. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Zheng, C.; Tong, S.; Eynard, B. A personalized requirement identifying model for design improvement based on user profiling. AI EDAM 2020, 34, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User Profile. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 2022. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_profile (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Farid, M.; Elgohary, R.; Moawad, I.; Roushdy, M. User Profiling Approaches, Modeling, and Personalization. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Informatics & Systems (INFOS 2018), Cairo, Egypt, 10–12 December 2018; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3389811 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Gu, Y.; Ding, Z.; Wang, S.; Yin, D. Hierarchical user profiling for e-commerce recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawashin, B.; Lafi, M.; Kanan, T.; Mansour, A. An efficient hybrid similarity measure based on user interests for recommender systems. Expert Syst. 2020, 37, e12471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Ramos, J.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Dey, A.K.; Pan, G. User profiling from their use of smartphone applications: A survey. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2019, 59, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazanos, D.M.; Olesen, H.; Hammershøj, A.D.; Heinze, E.K.S.; Bessler, S.; Zeiss, J.; Patrikakis, C.Z.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Amundsen, S.; Thuvesson, H.; et al. Specification of User Profile, Identity and Role Management for PNs and Integration to the PN Platform; IST Project MAGNET Beyond (My Personal Adaptive Global Net and Beyond) No. Deliverable D4.3.2 (D1.2.2) IST-027396; Aalborg Universitetsforlag: Aalborg, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, H.; Noll, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Hammershøj, A.; Sapuppo, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Elahi, N.; Chowdhury, M.; Heikkinen, S.; Sutterer, M.; et al. User Profiles, Personalization and Privacy: WWRF Outlook Series. 2009; pp. 22–23. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/user-profiles-personalization-and-privacy-wwrf-outlook (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Wachter, S. Normative challenges of identification in the Internet of Things: Privacy, profiling, discrimination, and the GDPR. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2018, 34, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Taatgen, N. User Modeling. In Handbook of Human Factors in Web Design; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 424–439. ISBN 9780805846119. [Google Scholar]

- Dhelim, S.; Aung, N.; Ning, H. Mining user interest based on personality-aware hybrid filtering in social networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 206, 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Song, Z.; Ma, Q. User interest model based on hybrid behaviors interest rate. Appl. Res. Comput. 2016, 3, 661–664. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Choo, K.K.R.; Ashman, H. User profiling in intrusion detection: A review. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 72, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, C.; Schutt, R. Statistical Inference, Exploratory Data Analysis, and the Data Science Process, Doing Data Science. In Doing Data Science; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sevastopol, CA, USA, 2014; Chapter 2; pp. 17–50. ISBN 9781449358655. [Google Scholar]

- Adèr, H.J. Phases and initial steps in data analysis. In Advising on Research Methods: A Consultant’s Companion; Adèr, H.J., Mellenbergh, G.J., Hand, D.J., Eds.; Johannes van Kessel Pub.: Huizen, The Netherlands, 2008; Chapter 14; pp. 333–356. ISBN 9789079418015. [Google Scholar]

- User Modeling. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 2022. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_modeling (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Fischer, G. User Modeling in Human–Computer Interaction. User Modeling User-Adapt. Interact. 2001, 11, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostolányová, K.; Klubal, L. Use of user modeling for personalization. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1978, p. 060017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusilovsky, P. Adaptive hypermedia. User Modeling User-Adapt. Interact. 2001, 11, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Naser, S.S.; Alamawi, W.W.; Alfarra, M.F. Rule Based System for Diagnosing Wireless Connection Problems Using SL5 Object. 2016. Available online: https://philpapers.org/go.pl?aid=ABURBS (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Ricci, F.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Introduction to Recommender Systems Handbook. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Kantor, P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; p. 165. ISBN 978-0-12-518406-9. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, C. Encyclopedia Britannica: Definition of Data Mining. Available online: http://www.britannica.com/technology/data-mining (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Ghorbani, A.; Zhang, J. GUMSAWS: A Generic User Modeling Server for Adaptive Web Systems. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference on Communication Networks and Services Research (CNSR ‘07), Frederlcton, NB, USA, 14–17 May 2007; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.; Salamó, M.; Coyle, L.; McGinty, L.; Smyth, B.; Nixon, P. Cats: A synchronous approach to collaborative group recommendation. In Proceedings of the Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference (FLAIRS), Melbourne Beach, FL, USA, 11–13 May 2006; pp. 86–91. Available online: https://www.aaai.org/Papers/FLAIRS/2006/Flairs06-015.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Logesh, R.; Subramaniyaswamy, V. Exploring hybrid recommender systems for personalized travel applications. In Cognitive Informatics and Soft Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Márquez, J.O.; Ziegler, J. Hootle+: A group recommender system supporting preference negotiation. In Cyted-Ritos International Workshop on Groupware; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To Login or to Social Login. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/login-social-scout-stevenson (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Directive 95/46/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31995L0046 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Lopes, H.; Pires, I.M.; Sánchez San Blas, H.; García-Ovejero, R.; Leithardt, V. PriADA: Management and Adaptation of Information Based on Data Privacy in Public Environments. Computers 2020, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends in Online Shopping. A Global Nielsen Consumer Report. June 2010. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/Q1-2010-GOS-Online-Shopping-Trends-June-2010.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Neural Network. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neural_network (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Neural Networks. Chapter 10. Available online: https://natureofcode.com/book/chapter-10-neural-networks (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Gatziolis, K.G.; Boucouvalas, A.C. Discovering the impact of user profiling in e-services. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Telecommunications and Multimedia (TEMU), Heraklion, Greece, 28–30 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Samanta, D.; Sarma, M. Modeling user behaviour in research paper recommendation system. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logesh, R.; Subramaniyaswamy, V.; Vijayakumar, V.; Li, X. Efficient user profiling based intelligent travel recommender system for individual and group of users. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2019, 24, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.M.; Pavan, M.C.; Paraboni, I. User profiling and satisfaction inference in public information access services. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2022, 58, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, T.; Kabra, M.; Shankarmani, R. User Profiling Based Recommendation System for E-Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th India Council International Conference (Indicon), Rajkot, India, 13–15 December 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEke, C.I.; Norman, A.A.; Shuib, L.; Nweke, H.F. A survey of user profiling: State-of-the-art, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144907–144924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.; Al-Digeil, M.; Ahmed, S.S. Profiling Online Users: Emerging Approaches and Challenges. In Securing Social Networks in Cyberspace; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 221–240. ISBN 9781003134527. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, E.; Mihuandayani, M.; Raharjo, S.; Hartanto, A.D.; Adi, S. A Review on Social Media Based Profiling Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (iSemantic), Semarang, Indonesia, 19–20 September 2020; pp. 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourg, L.; Chatzidimitris, T.; Chatzigiannakis, I.; Gavalas, D.; Giannakopoulou, K.; Kasapakis, V.; Konstantopoulos, C.; Kypriadis, D.; Pantziou, G.; Zaroliagis, C. Enhancing shopping experiences in smart retailing. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aivalis, C.J.; Gatziolis, K.G.; Boucouvalas, A.C. Innovations in E-Systems for E-Commerce. In Innovations in E-Systems for Business and Commerce; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 301–337. ISBN 9781771885645. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.G.; An, J.; Kwak, H.; Salminen, J.; Jansen, B.J. Assessing the accuracy of four popular face recognition tools for inferring gender, age, and race. In Proceedings of the Twelfth international AAAI conference on Web and Social Media, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boucouvalas, A.C.; Aivalis, C.J.; Gatziolis, K.G. Integrating retail and e-commerce using Web Analytics and intelligent sensors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Business and Telecommunications, Seoul, Korea, 3–5 August 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivalis, C.J.; Gatziolis, K.G.; Boucouvalas, A.C. Evolving analytics for e-commerce applications: Utilizing big data and social media extensions. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Telecommunications and Multimedia (TEMU), Heraklion, Greece, 25–27 July 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, J.; Wei, W.; Zhu, N.; Yu, C. A Multi-Model Approach for User Portrait. Future Internet 2021, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| User Profile Type | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit user profile | Direct user interaction with the system. Users manually create and fill in main data. | Data are collected quickly. Data gathered are of high quality. Usually, users enter real information when they enroll. Users have full control over the information collected. Users decide what they want to share with the system. | Users may not want to provide much data. It lacks the ability to adapt to changes and user preferences. It is highly dependent on the user’s willingness to provide the information. Users may not write true information on the forms. Users who are willing to provide true information may not know how to express their interests. |

| Implicit user profile | The system learns dynamically from observing user interactions. | User’s information can be easily and automatically updated so that the system is always aware and more accurate about their preferences. Minimal user effort is required. | It takes more time to gather valuable information about users. If there is no repetition in the user’s actions the pattern cannot be discovered. The information cannot be changed or seen by the users. |

| Hybrid user profile | Combine the previous methods and adjust the user’s profile according to their preferences. | Advantages of both techniques. | Disadvantages of both techniques. |

| Gender | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success RATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 57 | 47 | 82% |

| Female | 43 | 37 | 86% |

| Total | 100 | 84 | 84% |

| Parent | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 32 | 12 | 37.5% |

| No | 68 | 37 | 54.4% |

| Total | 100 | 49 | 49% |

| Running | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 78 | 63 | 81% |

| Yes | 22 | 11 | 50% |

| Total | 100 | 74 | 74% 1 |

| Football | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success RATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 76 | 65 | 86% |

| Yes | 24 | 8 | 33% |

| Total | 100 | 73 | 73% 1 |

| Basketball | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 82 | 72 | 88% |

| Yes | 18 | 9 | 50% |

| Total | 100 | 81 | 81% 1 |

| Gymnastics | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 82 | 61 | 74% |

| Yes | 18 | 7 | 39% |

| Total | 100 | 68 | 68% 1 |

| Tennis | Real data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 86 | 76 | 88% |

| Yes | 14 | 7 | 50% |

| Total | 100 | 83 | 83% 1 |

| Hiking | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 80 | 67 | 84% |

| Yes | 20 | 4 | 20% |

| Total | 100 | 71 | 71% 1 |

| Swimming | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 79 | 64 | 81% |

| Yes | 21 | 9 | 43% |

| Total | 100 | 73 | 73% 1 |

| Cycling | Real Data from Questionnaires | Profiling System Accurate Predictions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 82 | 64 | 78% |

| Yes | 18 | 7 | 39% |

| Total | 100 | 71 | 71% 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gatziolis, K.G.; Tselikas, N.D.; Moscholios, I.D. Adaptive User Profiling in E-Commerce and Administration of Public Services. Future Internet 2022, 14, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi14050144

Gatziolis KG, Tselikas ND, Moscholios ID. Adaptive User Profiling in E-Commerce and Administration of Public Services. Future Internet. 2022; 14(5):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi14050144

Chicago/Turabian StyleGatziolis, Kleanthis G., Nikolaos D. Tselikas, and Ioannis D. Moscholios. 2022. "Adaptive User Profiling in E-Commerce and Administration of Public Services" Future Internet 14, no. 5: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi14050144

APA StyleGatziolis, K. G., Tselikas, N. D., & Moscholios, I. D. (2022). Adaptive User Profiling in E-Commerce and Administration of Public Services. Future Internet, 14(5), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi14050144