Quality by Design for the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cosmeceuticals

2.1. Definitions

2.2. Bioactives

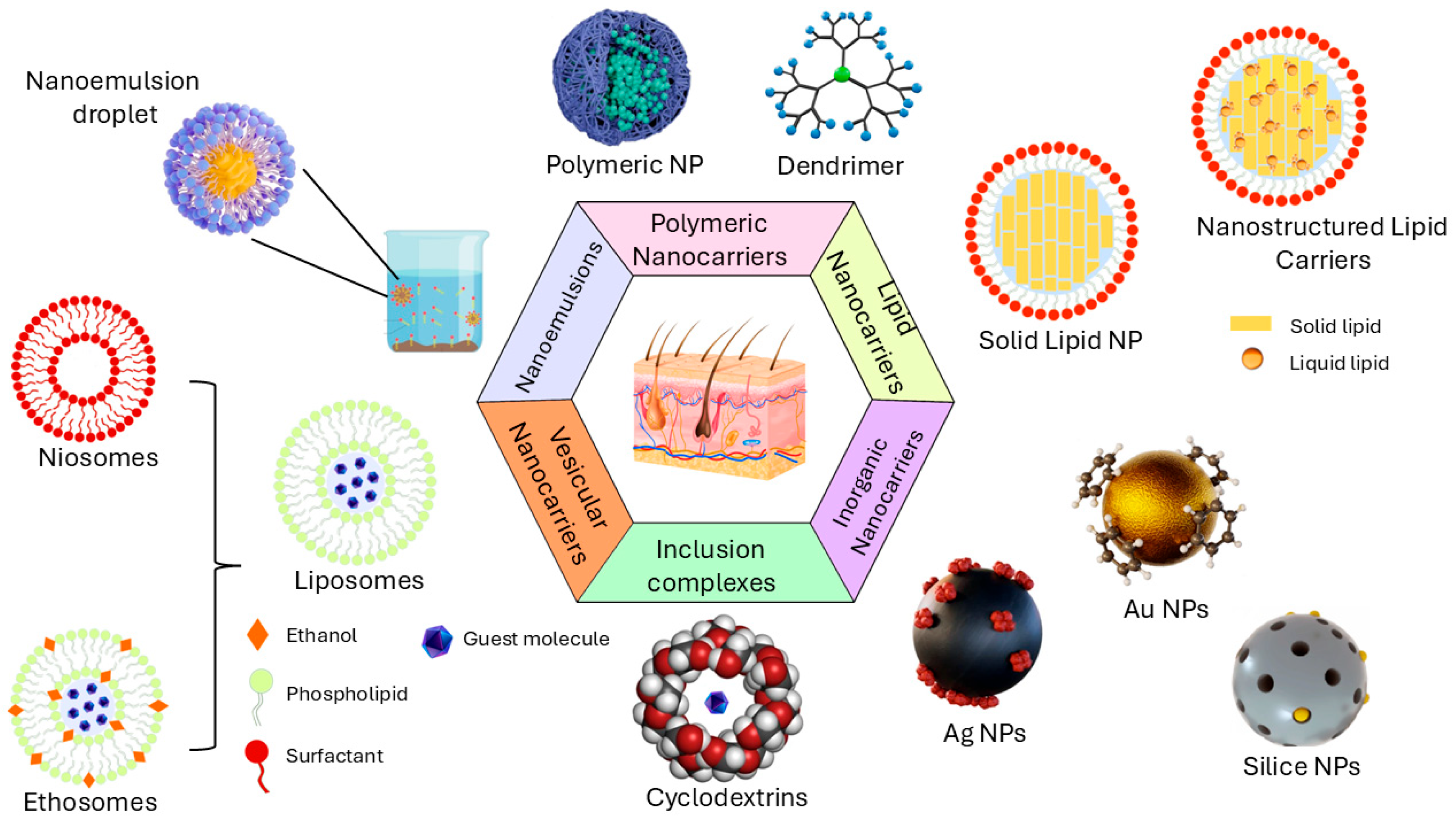

3. Nanocarriers for Skin Delivery

3.1. Polymeric-Based Nanoparticles

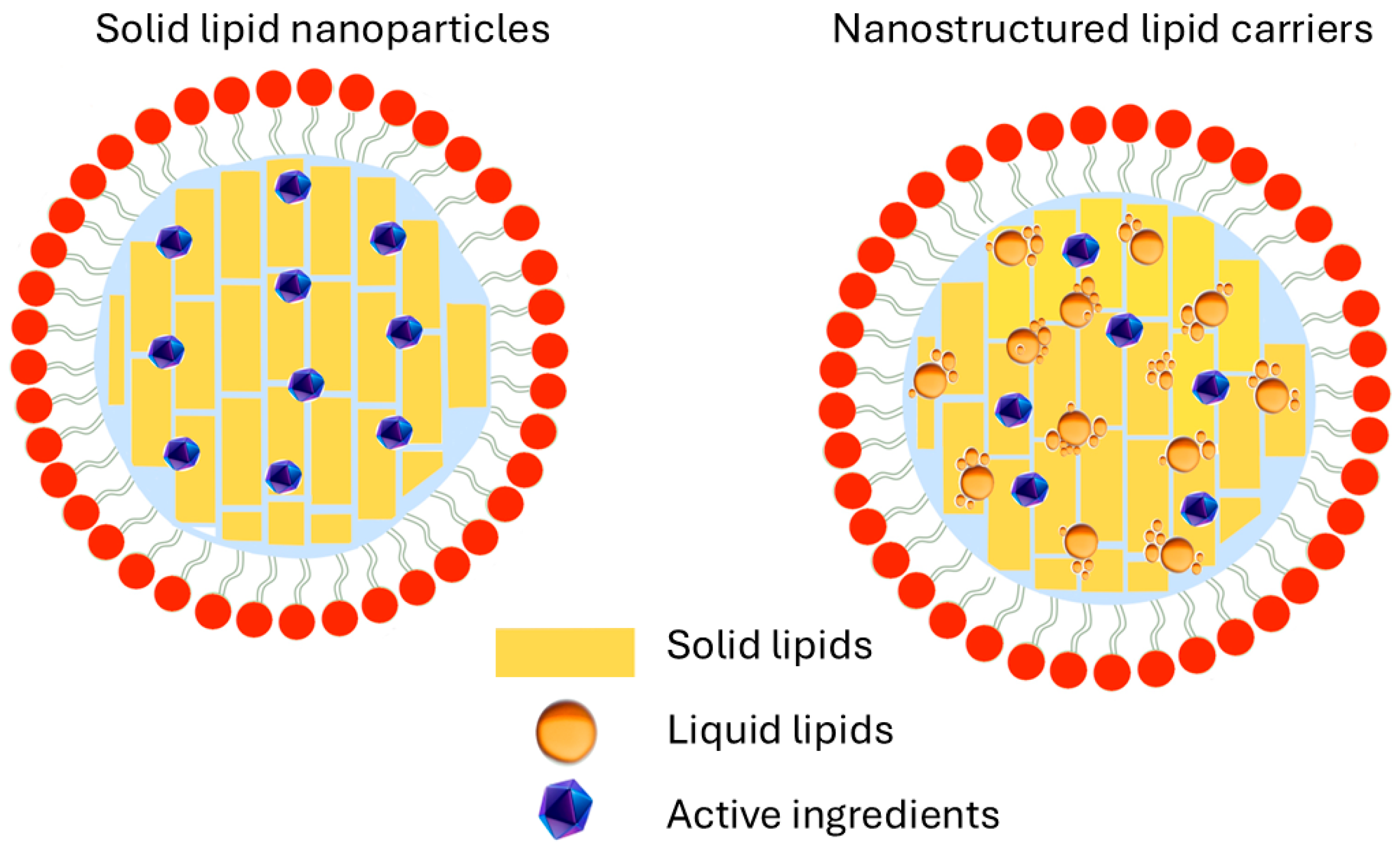

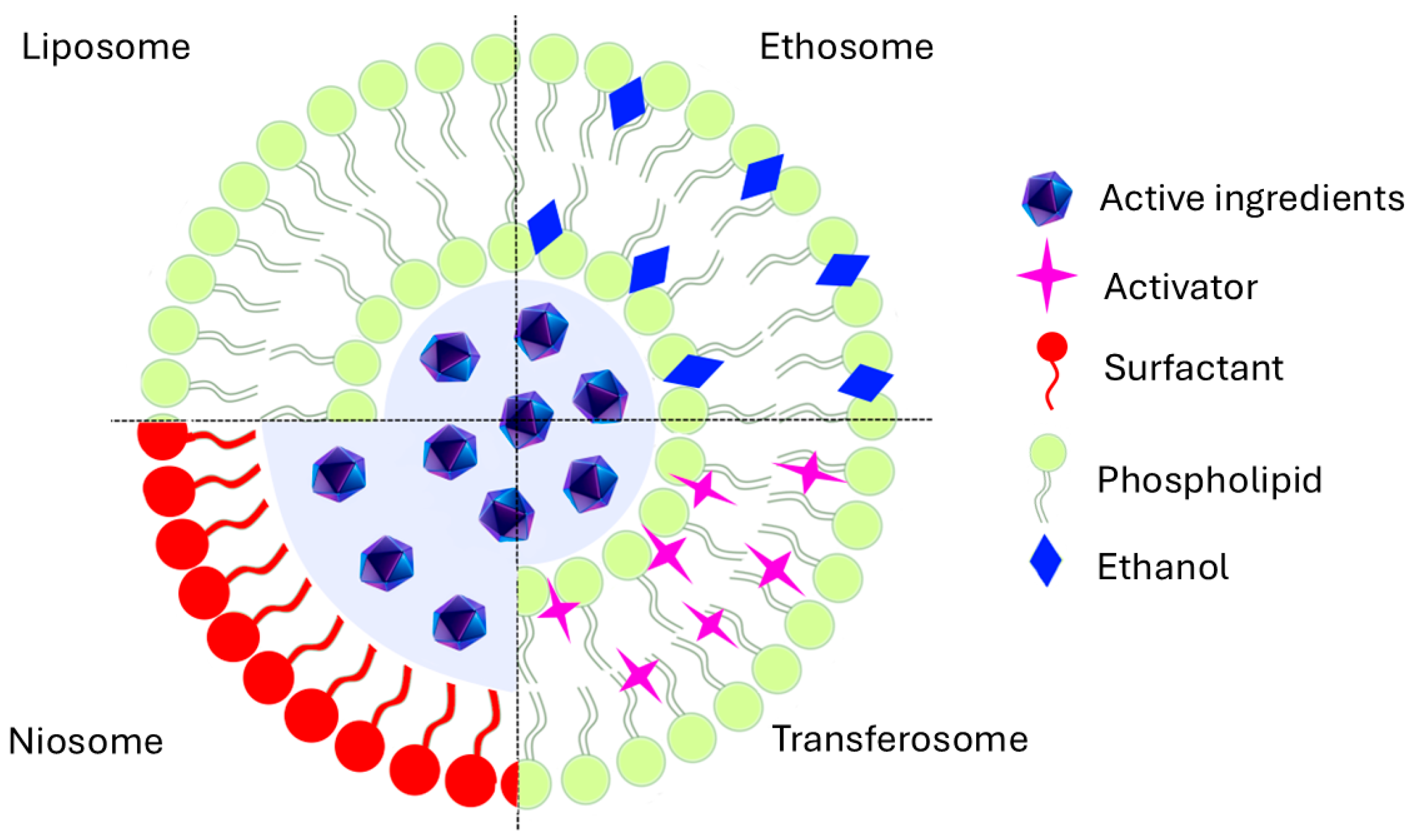

3.2. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles

3.3. Miscellaneous Nanosystems

4. Considerations for Implementation of QbD in the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals

4.1. Quality by Design Framework

4.2. Elements for QbD Implementation

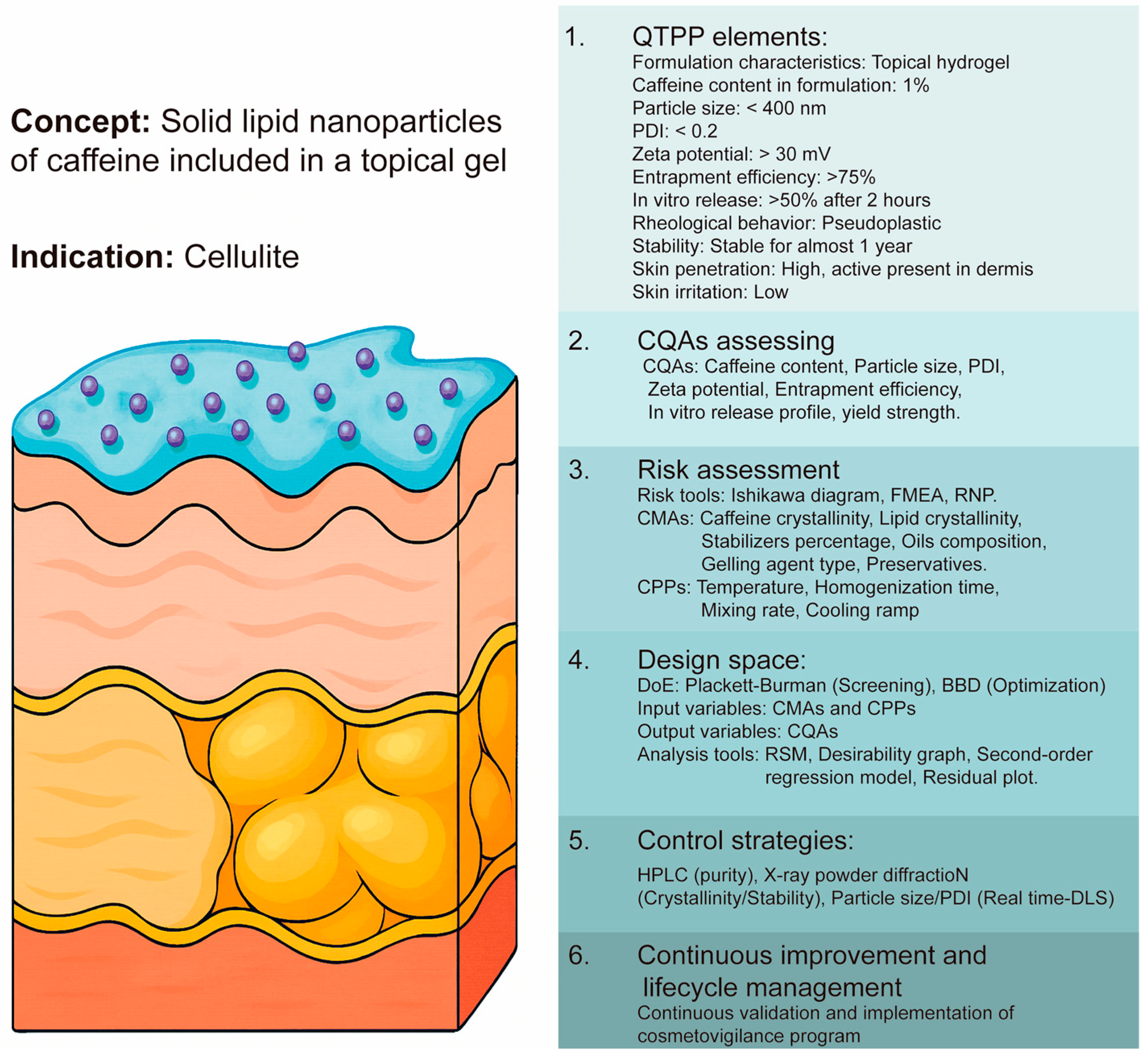

- Determination of Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP);

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) assessing;

- Risk assessment and determination of Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Parameter Process (CPPs);

- Design space by Desing of Experiments (DoE);

- Control strategies;

- Continuous improvement and Lifecycle management.

4.3. Determination of QTPP

- Cosmetic form, anatomical place of application, intended use;

- Container closure system and quantity of product per application;

- Aspects affecting permeation/retention in skin layers: dissolution, solubility, pKa, log P, molecular weight;

- Criteria of cosmetic product quality: solubility, stability, safety, active molecule release.

4.4. Considerations for Assessing Critical Quality Attributes in Nanocosmeceuticals

4.5. Application of Risk Analysis and Evaluation Tools

4.6. Design Space by DoE

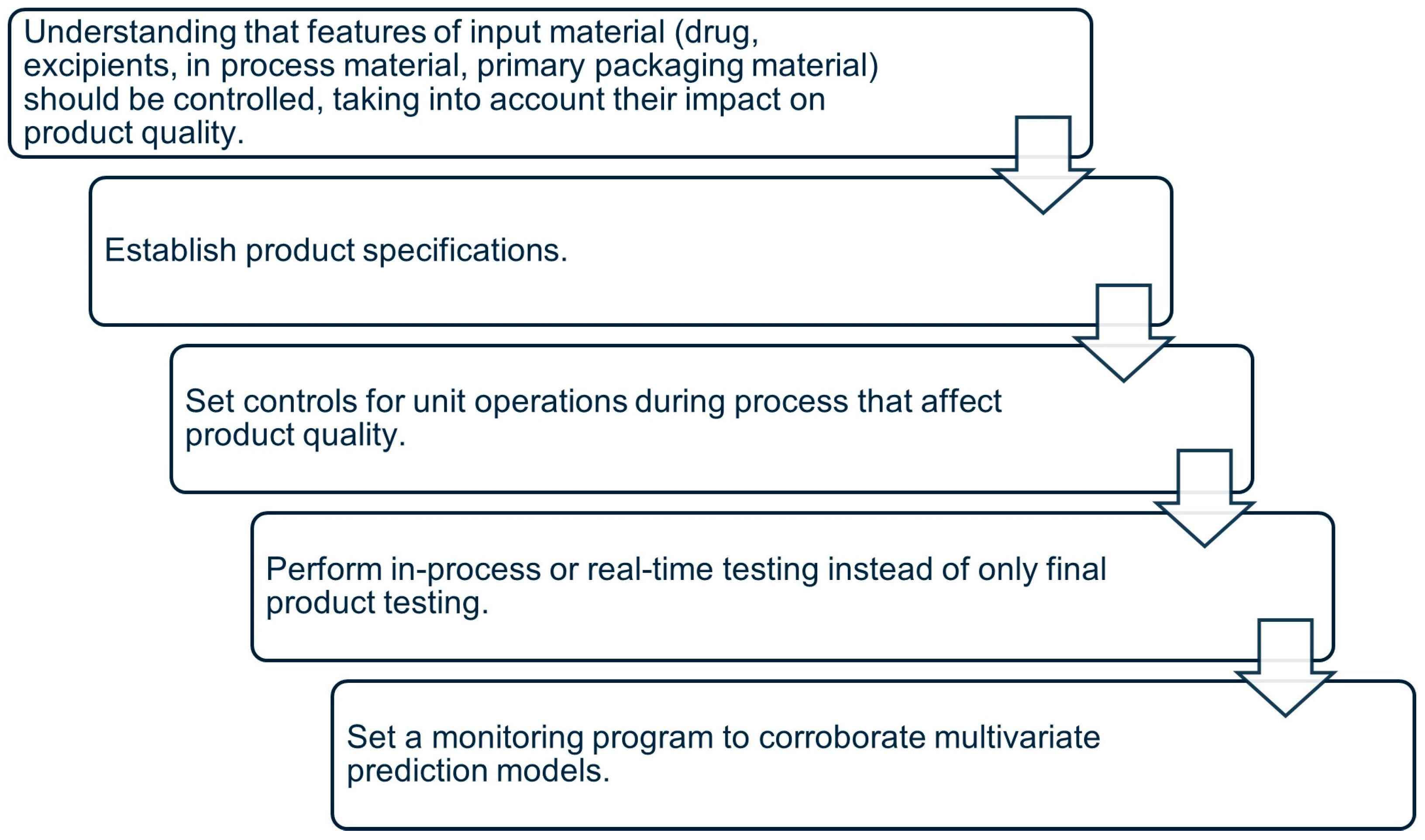

4.7. Implementation of Control Strategies

- Controls on material attributes (raw materials, general reagents, packaging materials, among others);

- Controls on active substances (integrity, purity, quality, and performance);

- Controls implicit in the design of the manufacturing process (unit operations, obtaining the cosmeceutical nanoformulation, sequence of purification steps, packaging);

- In-process controls (PAT monitoring).

4.8. Continupous Improvement and Lifecycle Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AgNP | Silver Nanoparticles |

| AuNP | Gold Nanoparticles |

| CMAs | Critical Material Attributes |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CQAs | Critical Quality Attributes |

| CpK | Capability Index |

| CPPs | Critical Process Parameters |

| DoE | Design of Experiments |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonisation |

| LNPs | Lipid Nanoparticles |

| NC | Nanocarrier |

| NEGs | Nanoemulsion Gels |

| NLCs | Nanostructured Lipid Carriers |

| OMC | Octyl Methoxycinnamate |

| PAT | Process Analytical Technology |

| PNP | Polymeric Nanoparticles |

| QbD | Quality by Design |

| QTPP | Quality Target Product Profile |

| SC | Stratum Corneum |

| SLNs | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles |

| USFDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Dhawan, S.; Sharma, P.; Nanda, S. Cosmetic Nanoformulations and Their Intended Use. In Nanocosmetics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.C.; Morais, F.; Simões, A.; Pereira, I.; Sequeira, J.A.D.; Pereira-Silva, M.; Veiga, F.; Ribeiro, A. Nanotechnology for the Development of New Cosmetic Formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milmile, P.S.; Patil, R.J.; M, S.; Wadher, K.J.; Umekar, M.J. Quality by Design: A Methodical Approach in Development of Nano Delivery System. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2021, 69, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Das, S.; Das, M.K. Nanocosmeceuticals: Concept, Opportunities, and Challenges. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari, A.M.; Khankari, R.V.; Chavan, P.J. Review on Study of Cosmeceuticals. Res. J. Top. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 14, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, A.; Chakraborty, T.; Das, M.K. Nanocosmeceuticals: Current Trends, Market Analysis, and Future Trends. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 525–558. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Products. Preliminary Opinion on Safety of Nanomaterials in Cosmetic Products; Scientific Committee on Consumer Products: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lohani, A.; Verma, A.; Joshi, H.; Yadav, N.; Karki, N. Nanotechnology-Based Cosmeceuticals. ISRN Dermatol. 2014, 2014, 843687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draelos, Z.D. Cosmeceuticals. Dermatol. Clin. 2014, 32, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singha, L.R.; Das, M.K. Dermatopharmacokinetics and Possible Mechanism of Action for Nanocosmeceuticals. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, A.; Chauhan, C. Emerging Trends of Nanotechnology in Beauty Solutions: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.; Dahiya, R. Potential of Colloidal Carriers for Nanocosmeceutical Applications. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 169–208. [Google Scholar]

- Dhapte-Pawar, V.; Kadam, S.; Saptarsi, S.; Kenjale, P.P. Nanocosmeceuticals: Facets and Aspects. Future Sci. OA 2020, 6, FSO613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, R.; Dange, P.; Nayakal, P.; Ramugade, P.; Pallavipatil, P. Emerging Trends of Nanomaterials in Cosmeceuticals. Asian J. Pharm. Res. 2023, 13, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, M.; Rana, R.; Sambhakar, S.; Chourasia, M.K. Nanocosmeceuticals: Trends and Recent Advancements in Self Care. Aaps Pharmscitech 2024, 25, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, E.B.; Fernandes, A.R.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Coutinho, T.E.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Souto, S.B.; Silva, A.M.; Santini, A. Nanomaterials for Skin Delivery of Cosmeceuticals and Pharmaceuticals. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Mohapatra, S.; Mishra, H.; Farooq, U.; Kumar, K.; Ansari, M.; Aldawsari, M.; Alalaiwe, A.; Mirza, M.; Iqbal, Z. Nanotechnology in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals—A Review of Latest Advancements. Gels 2022, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishampayan, P.; Rane, M.M. Herbal Nanocosmecuticals: A Review on Cosmeceutical Innovation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5464–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraqui, P.; Das, M.K. Herbal Cosmeceuticals for Beauty and Skin Therapy. In Nanocosmeceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 453–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, A.; Ahmad, I.Z.; Fatima, N.; Ansari, V.A.; Akhtar, J. Algal Bioactive Compounds in the Cosmeceutical Industry: A Review. Phycologia 2017, 56, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazitaeva, Z.; Drobintseva, A.; Chung, Y.; Polyakova, V.; Kvetnoy, I. Cosmeceutical Product Consisting of Biomimetic Peptides: Antiaging Effects in Vivo and in Vitro. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Pedriali Moraes, C. Bioactive Peptides: Applications and Relevance for Cosmeceuticals. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Amagai, M. Dissecting the Formation, Structure and Barrier Function of the Stratum Corneum. Int. Immunol. 2015, 27, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuplein, R.J.; Blank, I.H. Permeability of the Skin. Physiol. Rev. 1971, 51, 702–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, J.D.; Meinardi, M.M.H.M. The 500 Dalton Rule for the Skin Penetration of Chemical Compounds and Drugs. Exp. Dermatol. 2000, 9, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmowafy, M. Skin Penetration/Permeation Success Determinants of Nanocarriers: Pursuit of a Perfect Formulation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 203, 111748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Luo, D.; Chen, D.; Tan, X.; Bai, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Current Advances of Nanocarrier Technology-Based Active Cosmetic Ingredients for Beauty Applications. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 867–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnin, B.C.; Morgan, T.M. Transdermal Penetration Enhancers: Applications, Limitations, and Potential. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováčik, A.; Kopečná, M.; Vávrová, K. Permeation Enhancers in Transdermal Drug Delivery: Benefits and Limitations. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.M.; Hasan, O.A.; El Sisi, A.M. Preparation and Optimization of Lidocaine Transferosomal Gel Containing Permeation Enhancers: A Promising Approach for Enhancement of Skin Permeation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal Drug Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Penetration Enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.; Dagan, A.; Elia, J.; Merims, S.; Benny, O. Physical Properties of Gold Nanoparticles Affect Skin Penetration via Hair Follicles. Nanomedicine 2021, 36, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, J.; Kyotani, S. Influence of Nanoparticle Size on the Skin Penetration, Skin Retention and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babatunde, S.; Mojisola, A.; Iseoluwa, J.; Ejeromeghene, O.; Blessing, O.; Olayinka, J. Heliyon Polymeric Nanoparticles for Enhanced Delivery and Improved Bioactivity of Essential Oils. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folle, C.; Marqués, A.M.; Díaz-Garrido, N.; Espina, M.; Sánchez-López, E.; Badia, J.; Baldoma, L.; Calpena, A.C.; García, M.L. Thymol-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles: An Efficient Approach for Acne Treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jummes, B.; Sganzerla, W.G.; da Rosa, C.G.; Noronha, C.M.; Nunes, M.R.; Bertoldi, F.C.; Barreto, P.L.M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Poly-ε-Caprolactone Nanoparticles Loaded with Cymbopogon Martinii Essential Oil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.N.; Bhatia, A.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, R.; Kaur, G.; Dhawan, S. PLGA: A Unique Polymer for Drug Delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2015, 6, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; Baptista, R.; Ladeiras, D.; Madureira, A.M.; Teixeira, G.; Rosado, C.; Fernandes, A.S.; Ascensão, L.; Silva, C.O.; Reis, C.P.; et al. Production and Characterization of Nanoparticles Containing Methanol Extracts of Portuguese Lavenders. Measurement 2015, 74, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A.M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Venkatesh, D.N.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Eder, P.; Silva, A.M.; et al. Polymeric Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization, Toxicology and Ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Giottonini, K.Y.; Rodríguez-Córdova, R.J.; Gutiérrez-Valenzuela, C.A.; Peñuñuri-Miranda, O.; Zavala-Rivera, P.; Guerrero-Germán, P.; Lucero-Acuña, A. PLGA Nanoparticle Preparations by Emulsification and Nanoprecipitation Techniques: Effects of Formulation Parameters. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4218–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulka, K.; Sionkowska, A. Chitosan Based Materials in Cosmetic Applications: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayumi, N.S.; Sahudin, S.; Hussain, Z.; Hussain, M.; Samah, N.H.A. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Topical Delivery of Alpha and Beta Arbutin: Preparation and Characterization. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.; Elkheshen, S.A.; Kamel, A.O.; Nasr, M.; Moftah, N.H.; Ragai, M.H.; Elezaby, R.S.; El Hoffy, N.M. Functionalized Chitosan Nanoparticles for Cutaneous Delivery of a Skin Whitening Agent: An Approach to Clinically Augment the Therapeutic Efficacy for Melasma Treatment. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1212–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, B.; Whent, M.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q. Preparation and Characterization of Zein/Chitosan Complex for Encapsulation of α-Tocopherol, and Its in Vitro Controlled Release Study. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 85, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaolaor, A.; Kiti, K.; Pankongadisak, P.; Suwantong, O. Camellia Oleifera Oil-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Embedded in Hydrogels as Cosmeceutical Products with Improved Biological Properties and Sustained Drug Release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Allah, H.; Abdel-Aziz, R.T.A.; Nasr, M. Chitosan Nanoparticles Making Their Way to Clinical Practice: A Feasibility Study on Their Topical Use for Acne Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, S.; Pereira, M.N.; Cunha-Filho, M.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M. Targeted Clindamycin Delivery to Pilosebaceous Units by Chitosan or Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles for Improved Topical Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desfrançois, C.; Auzély, R.; Texier, I. Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Hydrogel Composites for Drug Delivery: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Radtke, M.; Wissing, S.A. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) in Cosmetic and Dermatological Preparations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, S131–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer-korting, M.; Mehnert, W.; Korting, H. Lipid Nanoparticles for Improved Topical Application of Drugs for Skin Diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assali, M.; Zaid, A. Features, Applications, and Sustainability of Lipid Nanoparticles in Cosmeceuticals. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, C.S.; Mehnert, W.; Schaller, M.; Korting, H.C.; Gysler, A.; Haberland, A.; Scha, M. Drug Targeting by Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Dermal Use. J. Drug Target. 2002, 10, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, T.; Bakhtiari, N.; Rad, I.A.; Ramezani, F. Formulation of Kaempferol in Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs): A Delivery Platform to Sensitization of MDA-MB468 Breast Cancer Cells to Paclitaxel. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 14591–14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, J.; Capello, L.; Martino, D.; Franco, V.; Dartora, C.; Araujo, G.L.B.D.; Ishida, K.; Lopes, L.B. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Development, Skin Targeting and Antifungal Efficacy of Topical Lipid Nanoparticles Containing Itraconazole. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 149, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Shankar, R.; Malik, V.; Sharma, N.; Mukherjee, T.K. Green Chemistry Based Benign Routes for Nanoparticle Synthesis. J. Nanopart. 2014, 2014, 302429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Morteza-semnani, K.; Akbari, J.; Siahposht-khachaki, A.; Firouzi, M.; Goodarzi, A.; Abootorabi, S.; Babaei, A. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology Brain Targeting of Venlafaxine HCl as a Hydrophilic Agent Prepared through Green Lipid Nanotechnology. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 66, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, J.; Saeedi, M.; Ahmadi, F.; Hashemi, S.M.H.; Babaei, A.; Yaddollahi, S.; Rostamkalaei, S.S.; Asare-Addo, K.; Nokhodchi, A. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Review of the Methods of Manufacture and Routes of Administration. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2022, 27, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, C.; Mehnert, W.; Lucks, J.S.; Müller, R.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Controlled Drug Delivery. I. Production, Characterization and Sterilization. J. Control. Release 1994, 30, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.J.; Runge, S.; Müller, R.H. Peptide-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN): Influence of Production Parameters. Int. J. Pharm. 1997, 149, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenning, V.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNTM) Based on Binary Mixtures of Liquid and Solid Lipids: A 1H-NMR Study. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 205, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Guedes, L.; Martinez, R.M.; Bou-Chacra, N.A.; Velasco, M.V.R.; Rosado, C.; Baby, A.R. An Overview on Topical Administration of Carotenoids and Coenzyme Q10 Loaded in Lipid Nanoparticles. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassayre, M.; Oline, A.; Orneto, C.; Wafo, E.; Abou, L.; Altié, A.; Claeys-Bruno, M.; Sauzet, C.; Piccerelle, P. Optimization of Solid Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation for Cosmetic Application Using Design of Experiments, PART II: Physical Characterization and In Vitro Skin Permeation for Sesamol Skin Delivery. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseri, M.; Golmohammadzadeh, S.; Arouiee, H.; Reza, M.; Neamati, H. Antifungal Activity of Zataria Multiflora Essential Oil-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles in-Vitro Condition. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2016, 19, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Yammine, J.; Chihib, N.-E.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Ismail, A.; Karam, L. Advances in Essential Oils Encapsulation: Development, Characterization and Release Mechanisms. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 3837–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenning, V.; Gohla, S.H. Encapsulation of Retinoids in Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN 1). J. Microencapsul. 2001, 18, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joukhadar, R.; Nižić Nodilo, L.; Lovrić, J.; Hafner, A.; Pepić, I.; Jug, M. Functional Nanostructured Lipid Carrier-Enriched Hydrogels Tailored to Repair Damaged Epidermal Barrier. Gels 2024, 10, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowska, M.; Marzec, M.; Jankowiak, W.; Nowak, I. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Incorporated with Retinol and Pentapeptide-18—Optimization, Characterization, and Cosmetic Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkm, E.; Gokce, E.H.; Ozer, O. Development and Evaluation of Coenzyme Q10 Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticle Hydrogel for Enhanced Dermal Delivery. Acta Pharm. 2013, 63, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samprasit, W.; Suriyaamporn, P.; Sriamornsak, P.; Opanasopit, P.; Chamsai, B. Resveratrol-Loaded Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Topical Delivery: Comparative Physical Properties and Antioxidant Activity. OpenNano 2024, 19, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Silva, A.L.; Guerra, C.; Peixoto, D.; Pereira-Silva, M.; Zeinali, M.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Castro, R.; Veiga, F. Ethosomes as Nanocarriers for the Development of Skin Delivery Formulations. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 947–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, M.L.; Manconi, M.; Nacher, A.; Carbone, C.; Valenti, D.; Maccioni, A.M.; Sinico, C.; Fadda, A.M. Development of Novel Diolein–Niosomes for Cutaneous Delivery of Tretinoin: Influence of Formulation and in Vitro Assessment. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 477, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, İ.; Aslan, M.; Yaman, Ü.; Gultekinoglu, M.; Çalamak, S.; Kart, D.; Ulubayram, K. Liposome-Based Combination Therapy for Acne Treatment. J. Liposome Res. 2020, 30, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-T.; Shen, L.-N.; Wu, Z.-H.; Zhao, J.-H.; Feng, N.-P. Comparison of Ethosomes and Liposomes for Skin Delivery of Psoralen for Psoriasis Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 471, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, V.; Moon, J.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Liposomes for Delivery of Antioxidants in Cosmeceuticals: Challenges and Development Strategies. J. Control. Release 2019, 300, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Stefanuto, L.; Gasperi, T.; Bruni, F.; Tofani, D. Lipid Nanovesicles for Antioxidant Delivery in Skin: Liposomes, Ufasomes, Ethosomes, and Niosomes. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, J.A.; Cruz, Y.F.d.; Girão, Í.C.; Souza, F.J.J.d.; Oliveira, W.N.d.; Alencar, É.d.N.; Amaral-Machado, L.; Egito, E.S.T.d. Beyond Traditional Sunscreens: A Review of Liposomal-Based Systems for Photoprotection. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione-Silva, L.; de Castro, E.G.; Nascimento, T.L.; Cintra, E.R.; Moreira, L.C.; Cintra, B.A.S.; Valadares, M.C.; Lima, E.M. Ascorbic Acid Encapsulated into Negatively Charged Liposomes Exhibits Increased Skin Permeation, Retention and Enhances Collagen Synthesis by Fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchianò, V.; Matos, M.; Serrano, E.; Álvarez, J.R.; Marcet, I.; Carmen Blanco-López, M.; Gutiérrez, G. Lyophilised Nanovesicles Loaded with Vitamin B12. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 365, 120129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xia, H.; Li, L.; Lee, R.J.; Xie, J.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Teng, L. Liposomal Vitamin D3 as an Anti-Aging Agent for the Skin. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Mathur, A.; Murugappan, S.; Sharma, A.; Tanwar, K.; Dua, K.; Singh, S.K.; Mazzola, P.G.; Yadav, D.N.; Rengan, A.K.; et al. Inorganic Nanoparticles in Dermopharmaceutical and Cosmetic Products: Properties, Formulation Development, Toxicity, and Regulatory Issues. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 192, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, L.; Qian, Y.; Lou, H.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X. Facile and Green Preparation of High UV-Blocking Lignin / Titanium Dioxide Nano Composites for Developing Natural Sunscreens. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 57, 15740–15748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matts, P.J.; Fink, B.; Goulart, J.M.; Wang, S.Q.; Meloni, M.; Marrot, L.; Shaath, N.A.; Osterwalder, U.; Herzog, B.; Gonzalez, H.; et al. Human Safety Review of “Nano” Titanium Dioxide and Zinc Oxide. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2010, 9, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, A.; Chuberre, B.; Marinovich, M. Safety of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Cosmetics. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, W.; Ong, J.; Nyam, K.L. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences Evaluation of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmeceutical and Potential Biosafety Complications. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, S.; Sakharwade, S. Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. Sci. Appl. 2016, 6, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, R.; Hochheim, S.; De Oliveira, C.C.; Riegel-Vidotti, I.C. Skin Interaction, Permeation, and Toxicity of Silica Nanoparticles: Challenges and Recent Therapeutic and Cosmetic Advances. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 614, 121439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Lee, Y.; Kuo, Y.; Lin, C. Development of Octyl Methoxy Cinnamates (OMC)/ Silicon Dioxide (SiO2) Nanoparticles by Sol-Gel Emulsion Method. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yang, Y.W.; Chen, Y.T.; Li, C.C.; Yu, H.C.; Chuang, Y.C.; Su, J.H.; Lin, Y.T. Preparation of UV- Fi Lter Encapsulated Mesoporous Silica with High Sunscreen Ability. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangshetti, J.N.; Deshpande, M.; Zaheer, Z.; Shinde, D.B.; Arote, R. Quality by Design Approach: Regulatory Need. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S3412–S3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.X.; Amidon, G.; Khan, M.A.; Hoag, S.W.; Polli, J.; Raju, G.K.; Woodcock, J. Understanding Pharmaceutical Quality by Design. AAPS J. 2014, 16, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Naquvi, K.J.; Haider, M.F.; Khan, M.A. Quality by Design- Newer Technique for Pharmaceutical Product Development. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C.; Safta, D.A.; Iurian, S.; Petrușcă, D.R.; Moldovan, M.L. QbD Approach in Cosmetic Cleansers Research: The Development of a Moisturizing Cleansing Foam Focusing on Thickener, Surfactants, and Polyols Content. Gels 2024, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Pharmaceutical Development Q8(R2); Step 4 Version 2009; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni-Motlagh, S.F.; Dolatabadi, R.; Baniassadi, M.; Baghani, M. Application of the Quality by Design Concept (QbD) in the Development of Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mao, S. Application of Quality by Design in the Current Drug Development. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasya, G.; Ozturk, C.; Aksu, B.; Tarimci, N. QbD Based Formulation Optimization of Semi-Solid Lipid Nanoparticles as Nano-Cosmeceuticals. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 66, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, D.A.; Jackson, L.M. (Eds.) Compounded Topical Pain Creams; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-309-67215-3. [Google Scholar]

- Trommer, H.; Neubert, R.H.H. Overcoming the Stratum Corneum: The Modulation of Skin Penetration. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 19, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsikó, S.; Csányi, E.; Kovács, A.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Gácsi, A.; Berkó, S. Methods to Evaluate Skin Penetration In Vitro. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namjoshi, S.; Dabbaghi, M.; Roberts, M.S.; Grice, J.E.; Mohammed, Y. Quality by Design: Development of the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) for Semisolid Topical Products. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lademann, J.; Richter, H.; Schanzer, S.; Knorr, F.; Meinke, M.; Sterry, W.; Patzelt, A. Penetration and Storage of Particles in Human Skin: Perspectives and Safety Aspects. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 77, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clogston, J.D.; Patri, A.K. Zeta Potential Measurement. Methods Mol Biol. 2011, 697, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soni, G.; Kale, K.; Shetty, S.; Gupta, M.K.; Yadav, K.S. Quality by Design (QbD) Approach in Processing Polymeric Nanoparticles Loading Anticancer Drugs by High Pressure Homogenizer. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union, European Parliament. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and the Council; Official Journal of the European Union; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.d.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano Based Drug Delivery Systems: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, K.; Kaplan, M.; Çalış, S. Effects of Nanoparticle Size, Shape, and Zeta Potential on Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 666, 124799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazayen, Z.M.; Ghoneim, A.M.; Elbatanony, R.S.; Basalious, E.B.; Bendas, E.R. Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology: From the Bench to the Market. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Stracke, F.; Hansen, S.; Schaefer, U.F. Nanoparticles and Their Interactions with the Dermal Barrier. Derm.-Endocrinol. 2009, 1, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardhiah Adib, Z.; Ghanbarzadeh, S.; Kouhsoltani, M.; Yari Khosroshahi, A.; Hamishehkar, H. The Effect of Particle Size on the Deposition of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles in Different Skin Layers: A Histological Study. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Chen, N.; Sun, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, Y. Size-Dependence of the Skin Penetration of Andrographolide Nanosuspensions: In Vitro Release-Ex Vivo Permeation Correlation and Visualization of the Delivery Pathway. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 641, 123065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Patel, M.; Soni, T.; Suhagia, B. Topical Arginine Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: Development and Characterization by QbD Approach. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management—Scientific Guideline; European Medicines Agency (EMA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-B.; Kwack, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kacew, S.; Lee, B.-M. Current Opinion on Risk Assessment of Cosmetics. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2021, 24, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuqaydan, A.M. The Dark Side of Beauty: An in-Depth Analysis of the Health Hazards and Toxicological Impact of Synthetic Cosmetics and Personal Care Products. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1439027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, J.K. A Brief Introduction to Design of Experiments. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Dig. 2007, 27, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Waghule, T.; Dabholkar, N.; Gorantla, S.; Rapalli, V.K.; Saha, R.N.; Singhvi, G. Quality by Design (QbD) in the Formulation and Optimization of Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticles (LCNPs): A Risk Based Industrial Approach. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, I.M.; Pinto, C.F.F.; Moreira, C.d.S.; Saviano, A.M.; Lourenço, F.R. Design of Experiments (DoE) Applied to Pharmaceutical and Analytical Quality by Design (QbD). Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54, e01006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstedt, T.; Seifert, E.; Abramo, L.; Thelin, B.; Nyström, Å.; Pettersen, J.; Bergman, R. Experimental Design and Optimization. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1998, 42, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Pharmaceutical Quality System Q10; Step 4 Version 2008; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Harmonised Guideline: Development and Manufacture of Drug Substances (Chemical Entities and Biotechnological/Biological Entities) Q11; Step 4 Version 2011; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, B.; Liu, T.-W.; Mei, H.-C.; Kuo, I.-C.; Surboyo, M.D.C.; Lin, H.-M.; Lee, C.-K. Herbal Nanoemulsions in Cosmetic Science: A Comprehensive Review of Design, Preparation, Formulation, and Characterization. J. Food Drug Anal. 2024, 32, 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittaway, P.M.; Chingono, K.E.; Knox, S.T.; Martin, E.; Bourne, R.A.; Cayre, O.J.; Kapur, N.; Booth, J.; Capomaccio, R.; Pedge, N.; et al. Exploiting Online Spatially Resolved Dynamic Light Scattering and Flow-NMR for Automated Size Targeting of PISA-Synthesized Block Copolymer Nanoparticles. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH M4Q(R1) The Common Technical Document for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: Quality—Quality Overall Summary of Module 2—Module 3: QualitSE: QUALITY—M4Q(R1) 2002; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Nanosystem | Characteristics | Considerations for QbD Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Encapsulate lipophilic or poor water-soluble bioactives Generally, size > 100 nm Modulable superficial charge | High feasibility of QbD implementation; CQAs should be related to physicochemical properties and loading capability. Manufacturing process is highly controllable and control strategies viable to implement. The use of biopolymers or GRAS polymers guarantees fewer possibilities of regulatory restrictions. |

| Lipid-based | Encapsulate lipophilic or poor water-soluble bioactives High skin lipid compatibility Generally, size > 100 nm High occlusive effect | Very high feasibility of QbD implementation; CQAs should be related to physicochemical properties, stability, and loading capability. Manufacturing process is highly controllable and control strategies viable to implement. The use of GRAS lipids increases safety for consumers. Low possibilities of regulatory restrictions. |

| Vesicular nanocarriers | Encapsulate lipophilic or poor water-soluble or water-soluble bioactives High skin lipid compatibility Generally, size < 100 nm High skin penetration | Very high feasibility of QbD implementation; CQAs should be related to physicochemical properties, stability, and loading capability. Manufacturing process is highly variable but controllable and control strategies viable to implement. In the case of liposomes, it has more than 40 years on the market, with high consumer acceptability. |

| Inorganic nanoparticles | Used as-is or with adsorbed bioactives Generally, size < 100 nm High skin penetration | Low feasibility of QbD implementation; CQAs should be related to physicochemical properties, safety, and stability. Manufacturing process could be complicated to control; physical properties are highly dependent on synthesis route and precursors. Safety concerns related to skin bioaccumulation. |

| QTPP Element | Example of Target Parameter That Could Be Used | Characteristic Impacted | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmeceutical dose strength | % w/w IU | Efficacy Safety | The formulation should contain the cosmeceutical in an effective concentration based on the information of the efficacy studies. |

| Type of cosmetic vehicle (where the nanoformulation could be included) | Emulsion Gel Lotion Ointment Emulgel Suspension | Quality Efficacy Safety | The type and composition of cosmetic dosage form impact the sensorial profile and consumer acceptance and also influence the permeation rate of the cosmeceutical [98]. Similarly, vehicle formulation could include components that promote or reduce transdermal permeation, modulating efficacy and irritation of bioactives [99]. |

| Site of application | Facial skin Eye contour Eyelid Body skin Hands Scalp Cuticle Legs | Safety | Although cosmeceuticals are intended to be applied to the skin, there are significant differences in the structure of the skin depending on the anatomical site. Therefore, the formulation of the vehicle must consider differences such as thickness, amount of lipids and water, hair density, and degree of sun exposure, among others. |

| In vitro permeation of cosmeceutical (from whole formulation) | Skin permeation rate Skin penetration depth | Efficacy Safety | In vitro release testing evaluates the ability of a formulation to deliver cosmeceuticals at the appropriate rate and depth at the site of application, contributing to building the safety–efficacy profile of the product [100]. |

| Stability | At least 12 months shelf life at room temperature | Quality Efficacy | Stability involves the assessment of physical and chemical changes and proper microbiological preservation. The cosmetic product must maintain quality and functionality standards when stored under appropriate conditions. |

| pH | Near to skin pH 5.5 | Efficacy Safety | The pH of the vehicle should be adjusted near to the skin physiological pH to avoid irritation; also, pH should be adjusted to assure chemical stability of the cosmeceutical and the physical performance of the vehicle during its shelf life. |

| Rheological/Textural profile | Viscosity Yield stress value G modulus value Distance of penetration value Force of penetration value Bioadhesion force value | Quality | Rheological and textural characteristics have an impact on cosmeceutical release from the nanocarrier and in skin retention of nanosystems [101]. In addition, rheological properties influence physical stability and sensorial profile. |

| Sensorial profile | Absorption Spreadability Pick-up Stickiness Brightness Oily | Quality | The sensory attributes of cosmetic products are largely decisive for the acceptance or rejection of the product by consumers. |

| Microbiological innocuity | Less than 100 CFU/g of aerobic mesophilic microorganism and absence of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, and Escherichia coli | Safety | Microbiological innocuity ensures that cosmetic products are safe for use and have been produced under good manufacturing practices. |

| QTPP Element | Example of Target Parameter That Could Be Used | Characteristic Impacted | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of material | Inorganic, polymeric, lipid | Safety Efficacy | The excipients play an important role in the physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles. The selection of the appropriate material is key for providing controlled release, bioadhesion, skin retention, compatibility bioactive-matrix, protection, biodegradability, etc. |

| Particle size | Hydrodynamic diameter | Quality Efficacy Safety | The particle size is one of the most relevant parameters to optimize, as it can affect nanoparticle skin penetration, adherence, clearance, and degradation [33]. For example, inorganic nanoparticles, at a size of 300–600 nm, were shown to penetrate and accumulate deeply into the hair follicles [102]. |

| Size distribution | Polydispersity index | Quality | The PDI is an estimation of the uniformity of the nanoparticle size distribution; the lower the PDI, the greater the monodispersity. It could be considered an indicative parameter to control quality batch-by-batch during manufacturing. |

| Zeta potential | >30 mv | Quality | The zeta potential is a measure of the surface charge of nanoparticles, and this value defines their physical stability when they are suspended in an aqueous medium. It is considered that a value greater than 30 mV, whether positive or negative, is indicative of excellent stability, since there is sufficient electrostatic repulsion so that the particles do not aggregate [102]. On the other hand, the charge exhibited by the nanoparticles also participates in the interaction with the stratum corneum and in the retention of nanoformulations on the skin. |

| Entrapment or encapsulation efficiency | % w/w | Efficacy | The entrapment or encapsulation efficiency (EE%) in nanoparticle preparation is a measure of the total cosmeceutical added minus the free or the non-entrapped cosmeceutical over the total drug added [103]. The physicochemical characteristics of the cosmeceutical (Log P, ionization, charge, polarity, etc.) determine the %EE, in addition to factors inherent to the preparation method, such as solvent extraction method or pH conditions. |

| Loading capacity | Mass, % w/w | Efficacy | Loading capacity is defined as the exact amount of cosmeceutical that is included in the nanoparticles as dry mass. The value depends on the physicochemical properties and the structure of the carrier material [104]. |

| Phase | Target | Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Risk identification | Identification of potential CPPs and CMAs | Ishikawa diagram (fishbone diagram), Preliminary Hazard Analysis |

| Risk analysis | Analysis of potential failure modes in a process, their causes, and effects | Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) |

| Risk evaluation | Provides a quantifiable evaluation of the occurrence, detectability, and severity of failure modes | Risk Matrix, Risk Ranking, Risk Priority Number |

| Failure Mode | Potential Causes | Potential Effects | Risk Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive skin penetration and systemic absorption | Particles < 100 nm that can reach functional layers of the dermis | Skin irritation, toxicity, systemic effects | Specify the particle size range (e.g., 150–350 nm) and conduct a Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) analysis. Perform an absorption analysis using Franz cells. |

| Instability or aggregation of nanoparticles in formulation | Lack of steric or electrostatic stabilization, pH shifts, inadequate storage conditions, mechanical stress during process, Ostwald ripening | Reduced efficacy, unpredictable release, aesthetic issues | Zeta potential and particle size analysis during stability test under stress conditions, during and after unit operations involved mechanical stress, excipient compatibility studies. |

| Loss of cosmeceutical load | Accelerated dissolution in vehicle, physical or chemical changes in bioactive, matrix nanoparticle degradation | Reduced efficacy | Accelerated stability testing, excipient compatibility studies. |

| Inconsistent manufacturing (batch variability) | Raw material variability, impurities | Variable efficacy, regulatory non-compliance | Quality assurance, process controls, implementation of PATs. |

| Occupational exposure | Formation of aerosols or dust | Production stoppages | Implement containment assessment by using local exhaust ventilation, wearing respirators, and conducting environmental monitoring. |

| Screening Designs | Optimization Design | Input Variables | Output Variables | Representation of Results | Validation of the Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-level full factorial Fractionate factorial Plackett–Burman Simplex | Box–Behnken Central composite 3-level factorial Simplex centroid | Concentration of bioactive Agitation rate Time of agitation Membrane pore size % of components Polymer inherent viscosity Point of melt of lipid | Particle size PDI Zeta potential Load capacity Bioactive content Penetration depth Skin irritation Viscosity pH Yield strength Stability (kinetic constant) | Pareto chart Main effects graph Surface graph Contours graph Ternary diagram Desirability plot | ANOVA analysis Multiple regression modeling Residual plot Levene’s test Normal plot Shapiro–Wilk’s test Kruskal–Wallis test |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leyva-Gómez, G.; Piñón-Segundo, E.; Urban-Morlan, Z.; Magaña-Vergara, N.E.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Jaime-Escalante, B.; Mendoza-Muñoz, N. Quality by Design for the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010062

Leyva-Gómez G, Piñón-Segundo E, Urban-Morlan Z, Magaña-Vergara NE, Quintanar-Guerrero D, Jaime-Escalante B, Mendoza-Muñoz N. Quality by Design for the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeyva-Gómez, Gerardo, Elizabeth Piñón-Segundo, Zaida Urban-Morlan, Nancy E. Magaña-Vergara, David Quintanar-Guerrero, Betzabeth Jaime-Escalante, and Néstor Mendoza-Muñoz. 2026. "Quality by Design for the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010062

APA StyleLeyva-Gómez, G., Piñón-Segundo, E., Urban-Morlan, Z., Magaña-Vergara, N. E., Quintanar-Guerrero, D., Jaime-Escalante, B., & Mendoza-Muñoz, N. (2026). Quality by Design for the Nanoformulation of Cosmeceuticals. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010062