Optimization of Microfluidizer-Produced PLGA Nano-Micelles for Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Efficacy: A Quality by Design Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Creation of CCD Experimental Matrix with Quality by Design (QbD) Approach

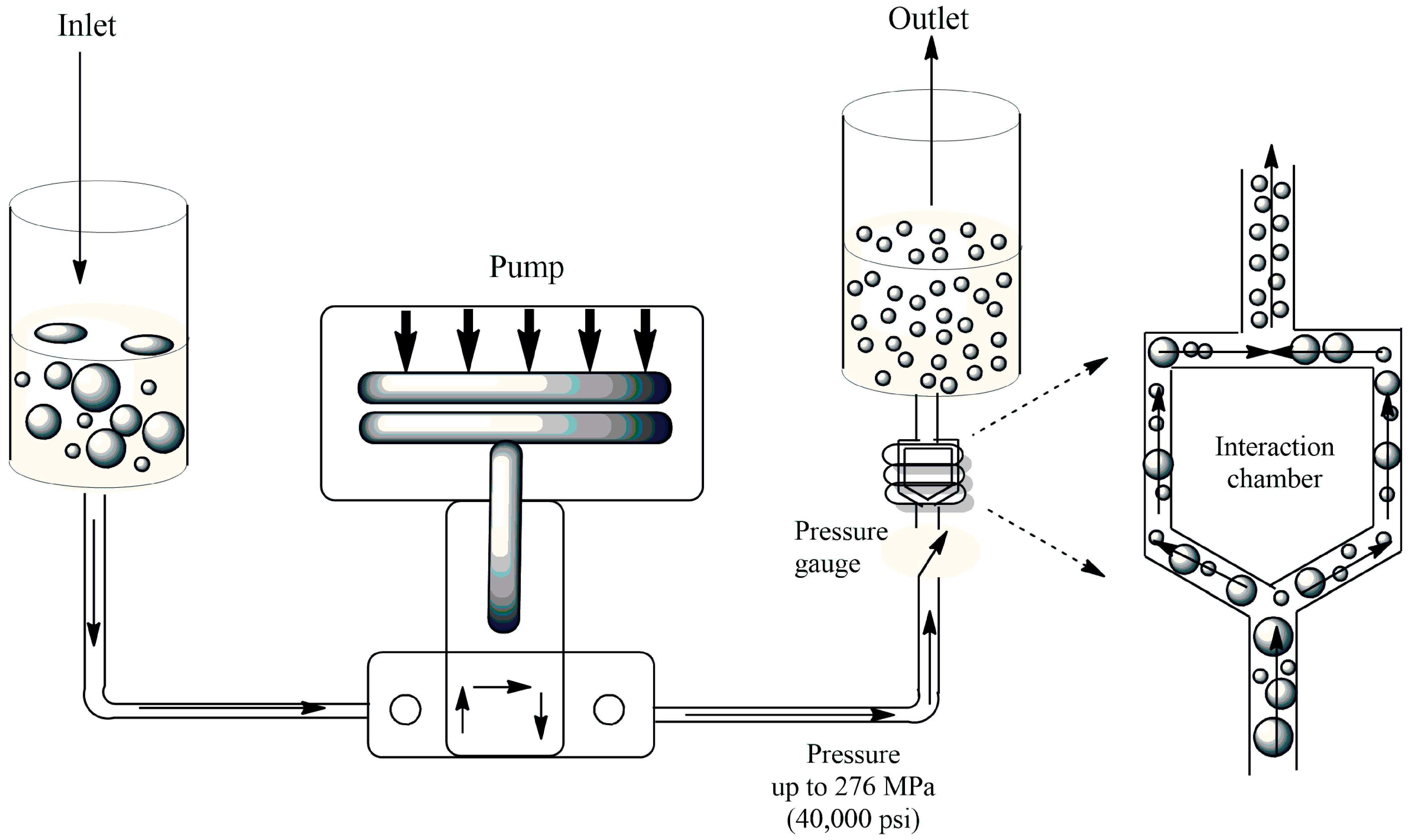

2.2.2. Synthesis of PLGANM Using Microfluidizer (PMFZ)

2.2.3. Synthesis of PLGANM Using Classic (Manual) O/W Method (POW)

2.2.4. Evaluation of the Responses to the CCD Variables

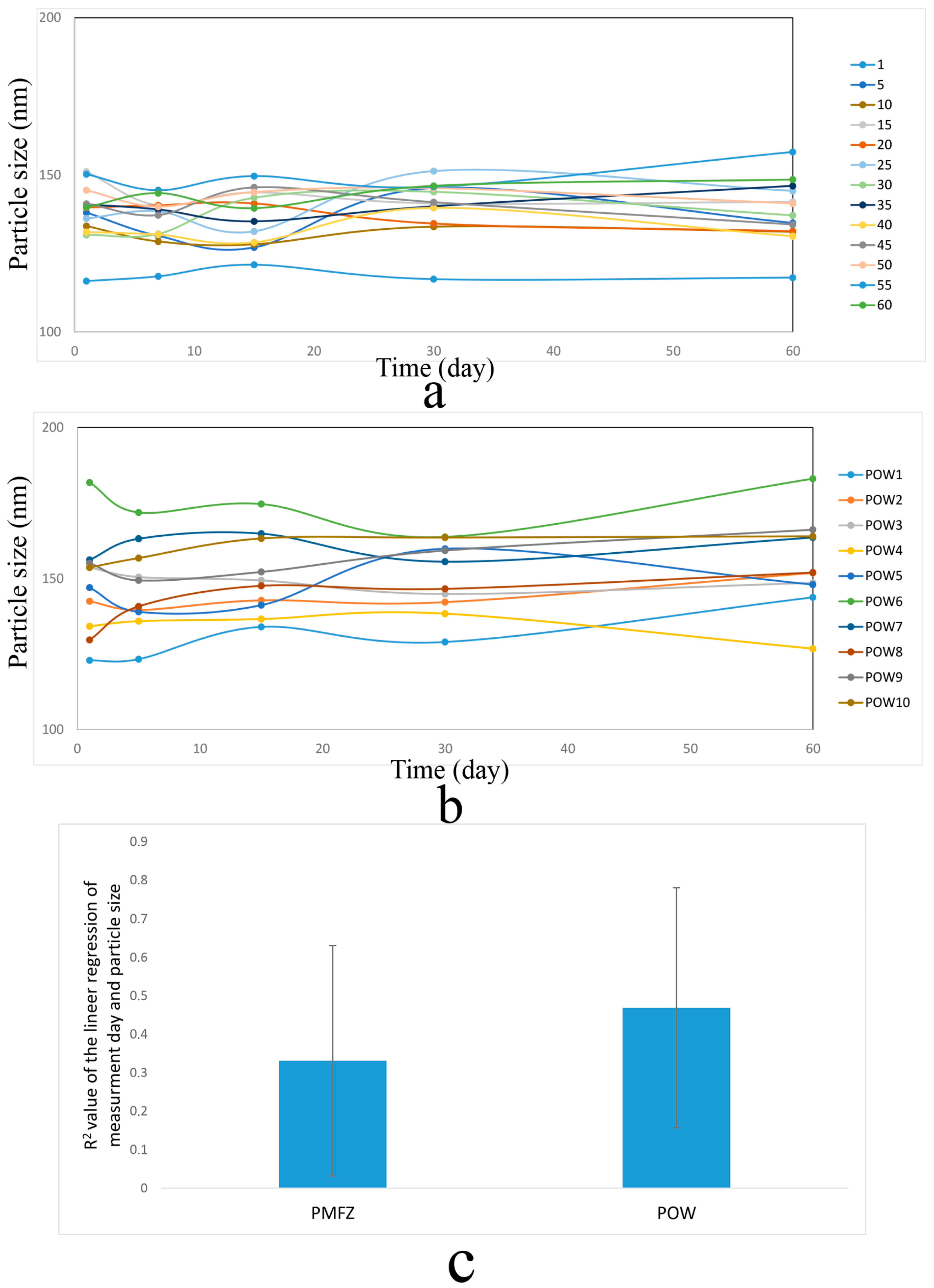

2.2.5. Comparison of the Stability of PMFZ and POW Particles Prior to the Optimization

2.2.6. Determination of the Optimized PMFZ (OPMFZ) Formulation Using QbD Approach

2.2.7. Determination of the Stability of OPMFZ, Drug Loading, and Comparison with POW

2.2.8. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Drug-Loaded OPMFZ

2.2.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

2.2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the Stability of PMFZ and POW Particles Prior to the Optimization

3.2. Experimental Design

3.2.1. Design Model and Data Analysis

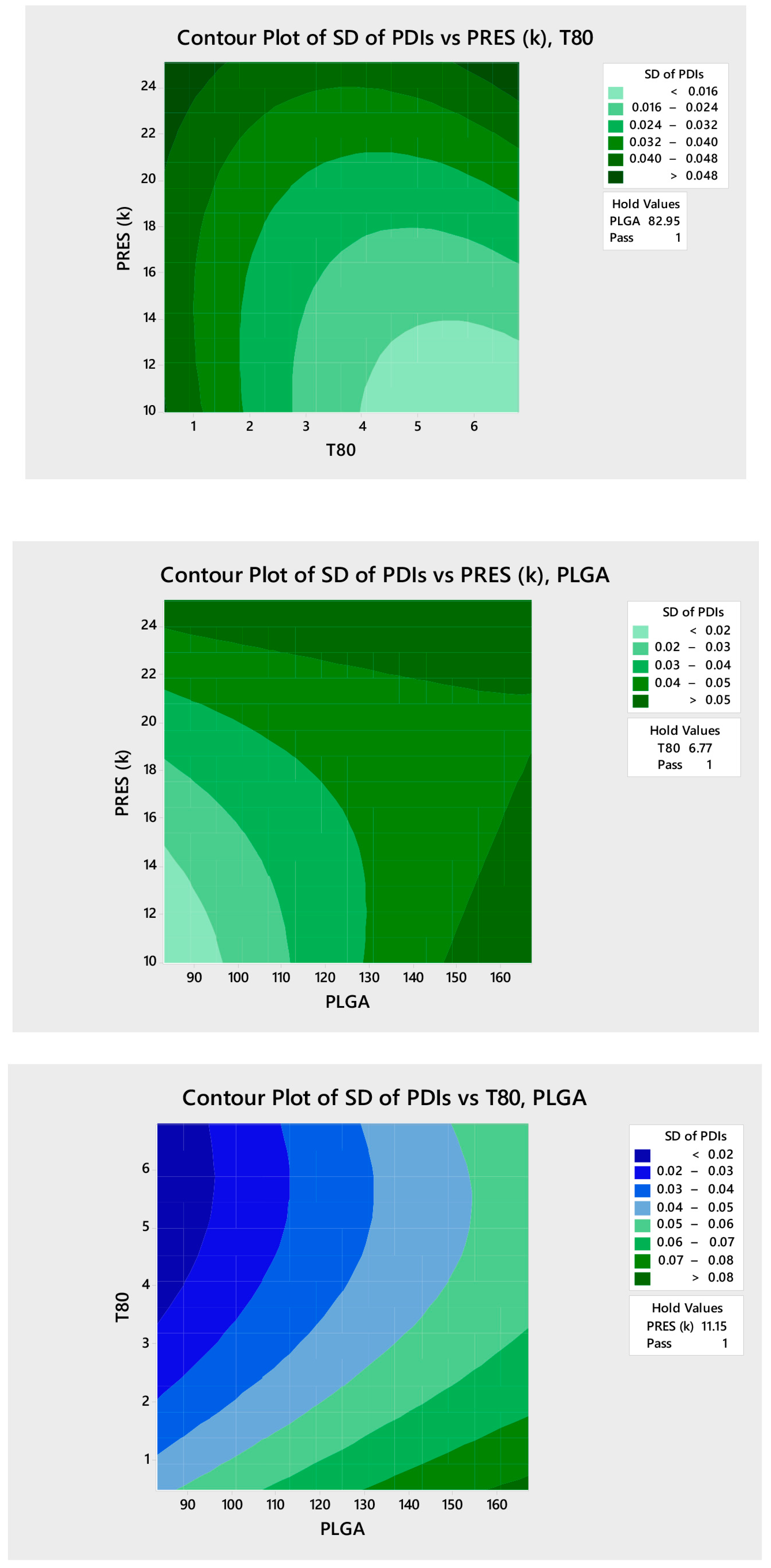

3.2.2. Determination of the Coded Variables for Production of the OPMFZ

3.2.3. Evaluating the OPMFZ Formulation

3.3. Determination of the Stability of OPMFZ, Drug Loading, and Comparison with POW

3.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Drug-Loaded OPMFZ

3.5. TEM Images of Curcumin-Carrying and Empty PLGANMs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QbD | Quality by Design |

| PLGA | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| MFZ | Microfluidizer |

| PMFZ | PLGANM produced by the MFZ method |

| POW | PLGANM produced using the traditional oil-in-water method |

| T80 | Tween 80 |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| OPMFZ | Optimized PMFZ |

| o/w | oil-in-water |

| NM | Nano-Micelles |

| (CQAs) | Critical quality attributes |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| PDI | Poly Dispersity Index |

References

- Nabar, G.M.; Mahajan, K.D.; Calhoun, M.A.; Duong, A.D.; Souva, M.S.; Xu, J.; Czeisler, C.; Puduvalli, V.K.; Otero, J.J.; Wyslouzil, B.E. Micelle-templated, poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for hydrophobic drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Su, F.; Li, S. Self-assembled micelles prepared from poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide)-poly (ethylene glycol) block copolymers for sustained release of valsartan. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, A.; Karlioti, G.; Balla, E.; Daniilidis, V.; Kalamas, T.; Stefanidou, M.; Bikiaris, N.D.; Christodoulou, E.; Koumentakou, I.; Karavas, E. Poly (lactic acid)-based microparticles for drug delivery applications: An overview of recent advances. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvi, M.; Yaqoob, A.; Rehman, K.; Shoaib, S.M.; Akash, M.S.H. PLGA-based nanoparticles for the treatment of cancer: Current strategies and perspectives. AAPS Open 2022, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balıbey, F.B.; Bahadori, F.; Ergin Kizilcay, G.; Tekin, A.; Kanimdan, E.; Kocyigit, A. Optimization of PLGA-DSPE hybrid nano-micelles with enhanced hydrophobic capacity for curcumin delivery. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2023, 28, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.S.; Winkle, H. Quality by design for biopharmaceuticals. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, B.; Sağıroğlu, A.A.; Özdemir, S. Design, optimization and characterization of coenzyme Q10-and D-panthenyl triacetate-loaded liposomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, K.; Shobha Rani, R. Design of experiments: Concept and applications of Plackett Burman design. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 2007, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlikaya, F.; Ozgen, A.; Vural, I.; Guven, O.; Karaagaoglu, E.; Khan, M.A.; Capan, Y. Development and evaluation of paclitaxel nanoparticles using a quality-by-design approach. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 3748–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, Z.; Kazdal, F.; Bahadori, F.; Ebrahimi, N. Quality-by-design model in optimization of PEG-PLGA nano micelles for targeted cancer therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 48, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operti, M.C.; Fecher, D.; van Dinther, E.A.; Grimm, S.; Jaber, R.; Figdor, C.G.; Tagit, O. A comparative assessment of continuous production techniques to generate sub-micron size PLGA particles. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 550, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operti, M.C.; Bernhardt, A.; Grimm, S.; Engel, A.; Figdor, C.G.; Tagit, O. PLGA-based nanomedicines manufacturing: Technologies overview and challenges in industrial scale-up. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 605, 120807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, S.N.; Das, N.G.; Das, S.K. Effect of microfluidization parameters on the physical properties of PEG-PLGA nanoparticles prepared using high pressure microfluidization. J. Microencapsul. 2009, 26, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotou, T.; Mesite, S.; Bernard, J.; Chomistek, K.; Fisher, R. Production of polymer nanosuspensions using microfluidizer processor based technologies. In Proceedings of the Nanotechnology Conference and Trade Show, Boston, MA, USA, 1–5 June 2008; pp. 688–691. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadori, F.; Eskandari, Z.; Ebrahimi, N.; Bostan, M.S.; Eroğlu, M.S.; Oner, E.T. Development and optimization of a novel PLGA-Levan based drug delivery system for curcumin, using a quality-by-design approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 138, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udepurkar, A.P.; Mampaey, L.; Clasen, C.; Cabeza, V.S.; Kuhn, S. Microfluidic synthesis of PLGA nanoparticles enabled by an ultrasonic microreactor. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkholief, M.; Kalam, M.A.; Anwer, M.K.; Alshamsan, A. Effect of solvents, stabilizers and the concentration of stabilizers on the physical properties of poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: Encapsulation, in vitro release of indomethacin and cytotoxicity against HepG2-cell. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, V.; Peres, C.; Ciman, T.; Rodrigues, C.; Viana, A.; Afonso, C.; Barata, T.; Brocchini, S.; Zloh, M.; Gaspar, R.S. Optimization of protein loaded PLGA nanoparticle manufacturing parameters following a quality-by-design approach. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 104502–104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.; Bahadori, F.; Akbas, F. Engineering of siRNA loaded PLGA Nano-Particles for highly efficient silencing of GPR87 gene as a target for pancreatic cancer treatment. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2020, 25, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, F.R. Particle size analysis by dynamic light scattering. Food Res. Int. 1994, 27, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszuba, M.; Corbett, J.; Watson, F.M.; Jones, A. High-concentration zeta potential measurements using light-scattering techniques. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 4439–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.; Hunter, R.J.; O’Brien, R.W. Effect of particle size distribution and aggregation on electroacoustic measurements of .zeta. potential. Langmuir 1992, 8, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shegokar, R.; Singh, K.; Müller, R. Production & stability of stavudine solid lipid nanoparticles—From lab to industrial scale. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 416, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, Y.; Satoh, K.; Yatomi, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Shirasawa, Y.; Kume, S. Detection of platelet aggregates with a particle counting method using light scattering. Anal. Biochem. 1994, 218, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tønnesen, H.; Másson, M.; Loftsson, T. Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids. XXVII. Cyclodextrin complexation: Solubility, chemical and photochemical stability. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 244, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manju, S.; Sreenivasan, K. Conjugation of curcumin onto hyaluronic acid enhances its aqueous solubility and stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 359, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Ronchi, M.; Petrangolini, G.; Bosisio, S.; Allegrini, P. Improved oral absorption of quercetin from quercetin phytosome®, a new delivery system based on food grade lecithin. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 44, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Peng, J.; Lei, D.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G. Optimization of genistein solubilization by κ-carrageenan hydrogel using response surface methodology. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2013, 2, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibetti, A.W.; Aydi, A.; Claumann, C.A.; Eladeb, A.; Adberraba, M. Correlation of solubility and prediction of the mixing properties of rosmarinic acid in different pure solvents and in binary solvent mixtures of ethanol + water and methanol + water from (293.2 to 318.2) K. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 216, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.Y.; Wang, Y.P.; Liu, Y.M.; Liu, B.; Liu, M.M.; Liu, B.M. Spectroscopic investigation of the anticancer alkaloid piperlongumine binding to human serum albumin from the viewpoint of drug delivery. Luminescence 2018, 33, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Schaich, K. Re-evaluation of the 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl free radical (DPPH) assay for antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4251–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, I.; Hariharan, S.; Kumar, M.R. PLGA nanoparticles in drug delivery: The state of the art. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2004, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, F.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R. Preparation and characterization of estradiol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles using homogenization-solvent diffusion method. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 16, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Pinnamaneni, S.; Das, N.; Das, S. Comparison of oil-in-water emulsions manufactured by microfluidization and homogenization. Die Pharm.-Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 58, 554–558. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic, M.; Uskokovic, D. Poly (lactide-co-glycolide)-based micro and nanoparticles for the controlled drug delivery of vitamins. Curr. Nanosci. 2009, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi-Samani, S.; Taghipour, B. PLGA micro and nanoparticles in delivery of peptides and proteins; problems and approaches. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2015, 20, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Wan, F.; Bera, H.; Cun, D.; Rantanen, J.; Yang, M. Quality by design thinking in the development of long-acting injectable PLGA/PLA-based microspheres for peptide and protein drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 585, 119441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Sovány, T.; Gácsi, A.; Ambrus, R.; Katona, G.; Imre, N.; Csóka, I. Synthesis and statistical optimization of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles encapsulating GLP1 analog designed for oral delivery. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, V.; Hawe, A.; Jiskoot, W. Critical evaluation of Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) by NanoSight for the measurement of nanoparticles and protein aggregates. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −α | −1 | 0 | +1 | +α | |

| X1: PLGA amounts (mg) | 83 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 167 |

| X2: T80 amounts (mL) | 0.5 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| X3: Pressure level in MFZ (psi × 1000) | 10 | 13 | 18 | 22 | 25 |

| X4: Pass number in MFZ | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Formulation Number | PLGA (mg) | T80 (mL) | Press. psi × 1000 | Pass | Formulation Number | PLGA (mg) | T80 (mL) | Press. Psi × 1000 | Pass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 1.8 | 22 | 1 | 31 | 125 | 6.8 | 18 | 1 |

| 2 | 125 | 3.6 | 25 | 5 | 32 | 100 | 1.8 | 13 | 3 |

| 3 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 33 | 100 | 5.5 | 13 | 5 |

| 4 | 150 | 5.5 | 22 | 1 | 34 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 |

| 5 | 125 | 6.8 | 18 | 3 | 35 | 150 | 5.5 | 13 | 5 |

| 6 | 83 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 36 | 150 | 1.8 | 22 | 3 |

| 7 | 150 | 5.5 | 13 | 1 | 37 | 150 | 1.8 | 22 | 5 |

| 8 | 100 | 1.8 | 13 | 5 | 38 | 125 | 3.6 | 25 | 3 |

| 9 | 125 | 0.5 | 18 | 3 | 39 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 |

| 10 | 100 | 5.5 | 13 | 1 | 40 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 |

| 11 | 150 | 5.5 | 13 | 3 | 41 | 100 | 5.5 | 22 | 3 |

| 12 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 42 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 |

| 13 | 167 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 43 | 150 | 1.8 | 13 | 3 |

| 14 | 150 | 1.8 | 13 | 5 | 44 | 100 | 5.5 | 13 | 3 |

| 15 | 150 | 1.8 | 13 | 1 | 45 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 |

| 16 | 100 | 1.8 | 13 | 1 | 46 | 125 | 3.6 | 25 | 1 |

| 17 | 83 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 | 47 | 125 | 0.5 | 18 | 1 |

| 18 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 | 48 | 150 | 5.5 | 22 | 5 |

| 19 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 49 | 125 | 0.5 | 18 | 5 |

| 20 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 | 50 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 |

| 21 | 100 | 1.8 | 22 | 3 | 51 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 |

| 22 | 125 | 3.6 | 10 | 3 | 52 | 100 | 5.5 | 22 | 5 |

| 23 | 125 | 3.6 | 10 | 5 | 53 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 |

| 24 | 100 | 5.5 | 22 | 1 | 54 | 125 | 6.8 | 18 | 5 |

| 25 | 150 | 1.8 | 22 | 1 | 55 | 167 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 |

| 26 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 | 56 | 100 | 1.8 | 22 | 5 |

| 27 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 | 57 | 125 | 3.6 | 10 | 1 |

| 28 | 167 | 3.6 | 18 | 3 | 58 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 |

| 29 | 83 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 | 59 | 150 | 5.5 | 22 | 3 |

| 30 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 5 | 60 | 125 | 3.6 | 18 | 1 |

| Formulation Number | PLGA (mg) | T80 (mL) |

|---|---|---|

| POW1 | 83 | 0.5 |

| POW2 | 83 | 6.8 |

| POW3 | 100 | 0.5 |

| POW4 | 100 | 6.8 |

| POW5 | 125 | 0.5 |

| POW6 | 125 | 6.8 |

| POW7 | 150 | 0.5 |

| POW8 | 150 | 6.8 |

| POW9 | 167 | 0.5 |

| POW10 | 167 | 6.8 |

| Size Distribution Measurement Methods | Formulation Method | Measurement Duration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ± STDV | 7 ± STDV | 15 ± STDV | 30 ± STDV | 60 ± STDV | ||

| Intensity | PMFZ | 138.46 ± 35 | 137.67 ± 25 | 136.05 ±28 | 138.72 ± 34 | 136.18 ± 35 |

| POW | 147.68 ± 24 | 147.04 ± 35 | 150.67 ± 28 | 150.33 ± 31 | 154.8 ± 33 | |

| Number | PMFZ | 100.85 ± 22 | 95.210 ± 29 | 99.315 ± 20 | 99.08 ± 30 | 95.62 ± 33 |

| POW | 98.586 ± 34 | 105.04 ± 32 | 97.84 ± 25 | 106.92 ± 29 | 100.82 ± 37 | |

| Volume | PMFZ | 125.86 ± 21 | 122.62 ± 31 | 123.41 ± 27 | 125.27 ± 31 | 121.38 ± 28 |

| POW | 132.63 ± 22 | 134.78 ± 25 | 134.47 ± 33 | 138.28 ± 21 | 139.2 ± 34 | |

| PDI | PMFZ | 0.08185 | 0.082183 | 0.079167 | 0.073017 | 0.088017 |

| POW | 0.162 | 0.0806 | 0.1093 | 0.1057 | 0.1045 | |

| Z-Average | PMFZ | 128.25 | 126.29 | 126.40 | 128.1467 | 125.4967 |

| POW | 135.97 | 135.94 | 135.99 | 137.75 | 138.82 | |

| Response Variable | Pass Number | Model Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Z-average (SDVzAVE) | 1 | SDVzAVE = 12.47 − 0.0303 PLGA − 1.670 T80 − 0.564 PRES (k) − 0.000027 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0994 T80 × T80 + 0.01202 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.00484 PLGA × T80 + 0.00170 PLGA × PRES (k) − 0.0136 T80 × PRES (k) |

| 3 | SDVzAVE = 12.84 − 0.0556 PLGA − 1.229 T80 − 0.479 PRES (k) − 0.000027 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0994 T80 × T80 + 0.01202 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.00484 PLGA × T80 + 0.00170 PLGA × PRES (k) − 0.0136 T80 × PRES (k) | |

| 5 | SDVzAVE = 7.55 − 0.0258 PLGA − 0.859 T80 − 0.489 PRES (k) − 0.000027 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0994 T80 × T80 + 0.01202 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.00484 PLGA × T80 + 0.00170 PLGA × PRES (k) − 0.0136 T80 × PRES (k) | |

| PDI (SDVPDI) | 1 | SDVPDI = −0.0165 + 0.001273 PLGA − 0.02022 T80 + 0.00015 PRES (k) − 0.000002 PLGA × PLGA + 0.001181 T80 × T80 + 0.000098 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.000019 PLGA × T80 − 0.000041 PLGA × PRES (k) + 0.000406 T80 × PRES (k) |

| 3 | SDVPDI = −0.0107 + 0.000997 PLGA − 0.01809 T80 + 0.00134 PRES (k) − 0.000002 PLGA × PLGA + 0.001181 T80 × T80 + 0.000098 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.000019 PLGA × T80 − 0.000041 PLGA × PRES (k) + 0.000406 T80 × PRES (k) | |

| 5 | SDVPDI = −0.0646 + 0.001246 PLGA − 0.01482 T80 + 0.00158 PRES (k) − 0.000002 PLGA × PLGA + 0.001181 T80 × T80 + 0.000098 PRES (k) × PRES (k) + 0.000019 PLGA × T80 − 0.000041 PLGA × PRES (k) + 0.000406 T80 × PRES (k) | |

| Zeta Potential (SDVZETA) | 1 | SDVZETA = −10.19 + 0.0794 PLGA + 0.158 T80 + 0.786 PRES (k) − 0.000092 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0015 T80 × T80 − 0.00593 PRES (k) × PRES (k) − 0.00001 PLGA × T80 − 0.00372 PLGA × PRES (k) − 0.0128 T80 × PRES (k) |

| 3 | SDVZETA = −8.75 + 0.0748 PLGA + 0.261 T80 + 0.683 PRES (k) − 0.000092 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0015 T80 × T80 − 0.00593 PRES (k) × PRES (k) − 0.00001 PLGA × T80 − 0.00372 PLGA × PRES (k) − 0.0128 T80 × PRES (k) | |

| 5 | SDVZETA = −11.50 + 0.0844 PLGA + 0.470 T80 + 0.751 PRES (k) − 0.000092 PLGA × PLGA + 0.0015 T80 × T80 − 0.00593 PRES (k) × PRES (k) − 0.00001 PLGA × T80 |

| Formulation Number | Responses (Standard Deviations) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SD * Z-Ave | SD * PDI | SD * Zeta | |

| 1 | 2.86 | 0.039 | 4.86 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 0.043 | 0.99 |

| 3 | 1.64 | 0.022 | 1.87 |

| 4 | 1.53 | 0.043 | 0.46 |

| 5 | 1.94 | 0.035 | 0.69 |

| 6 | 1.36 | 0.032 | 0.65 |

| 7 | 3.31 | 0.035 | 1.87 |

| 8 | 2.15 | 0.023 | 1.24 |

| 9 | 3.66 | 0.061 | 0.38 |

| 10 | 1.25 | 0.033 | 1.4 |

| 11 | 2.59 | 0.053 | 1.43 |

| 12 | 0.73 | 0.021 | 0.74 |

| 13 | 1.6 | 0.043 | 1.3 |

| 14 | 1.8 | 0.032 | 0.99 |

| 15 | 3.99 | 0.072 | 1.26 |

| 16 | 5.47 | 0.039 | 0.86 |

| 17 | 1.39 | 0.022 | 0.98 |

| 18 | 1.96 | 0.031 | 1.51 |

| 19 | 2.18 | 0.039 | 0.94 |

| 20 | 2.29 | 0.045 | 1.76 |

| 21 | 7.82 | 0.062 | 0.64 |

| 22 | 2.11 | 0.044 | 1.96 |

| 23 | 1.82 | 0.018 | 0.65 |

| 24 | 1.55 | 0.033 | 2.31 |

| 25 | 5.43 | 0.049 | 1.78 |

| 26 | 3.84 | 0.042 | 0.5 |

| 27 | 0.93 | 0.034 | 0.71 |

| 28 | 1.72 | 0.021 | 0.66 |

| 29 | 1.96 | 0.023 | 0.9 |

| 30 | 4.16 | 0.032 | 1.39 |

| 31 | 1.6 | 0.045 | 1.83 |

| 32 | 2.87 | 0.034 | 2.8 |

| 33 | 3.37 | 0.023 | 2.11 |

| 34 | 1.91 | 0.038 | 1.16 |

| 35 | 2.43 | 0.037 | 1.81 |

| 36 | 2.16 | 0.02 | 0.7 |

| 37 | 4.07 | 0.034 | 0.75 |

| 38 | 2.98 | 0.062 | 1.69 |

| 39 | 2.43 | 0.041 | 2.41 |

| 40 | 1.32 | 0.034 | 1.16 |

| 41 | 3.47 | 0.057 | 2.64 |

| 42 | 2.04 | 0.024 | 0.78 |

| 43 | 3.37 | 0.036 | 0.74 |

| 44 | 4.54 | 0.029 | 1.14 |

| 45 | 2.89 | 0.037 | 7.13 |

| 46 | 4.34 | 0.04 | 0.62 |

| 47 | 4.46 | 0.046 | 1.06 |

| 48 | 5.23 | 0.045 | 0.86 |

| 49 | 2.33 | 0.033 | 1.29 |

| 50 | 2.86 | 0.021 | 2.12 |

| 51 | 3.09 | 0.027 | 1.16 |

| 52 | 2.96 | 0.053 | 3.65 |

| 53 | 3.74 | 0.034 | 1.09 |

| 54 | 3.59 | 0.056 | 3.32 |

| 55 | 3.31 | 0.048 | 3.04 |

| 56 | 2.22 | 0.026 | 2.29 |

| 57 | 2.01 | 0.032 | 0.55 |

| 58 | 1.6 | 0.035 | 1.07 |

| 59 | 4.92 | 0.054 | 0.36 |

| 60 | 5.04 | 0.065 | 2.21 |

| Variable | Optimized Value |

|---|---|

| PLGA (mg) | 82.96 |

| T80 (mL) | 6.78 |

| Pressure (psi) | 11,000.00 |

| Pass Number | 1 |

| Response | Observed | Predicted | Residual |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD Z-average (nm) | 1.5301 | 1.53 | 0.0001 |

| SD PDI | 0.01225 | 0.0096 | 0.00265 |

| SD zeta potential (mV) | 0.512 | 0.48 | 0.032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Develi Arslanhan, E.N.; Bahadori, F.; Eskandari, Z.; Kasapoglu, M.Z.; Mankan, E. Optimization of Microfluidizer-Produced PLGA Nano-Micelles for Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Efficacy: A Quality by Design Approach. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010025

Develi Arslanhan EN, Bahadori F, Eskandari Z, Kasapoglu MZ, Mankan E. Optimization of Microfluidizer-Produced PLGA Nano-Micelles for Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Efficacy: A Quality by Design Approach. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeveli Arslanhan, Esma Nur, Fatemeh Bahadori, Zahra Eskandari, Muhammed Zahid Kasapoglu, and Erkan Mankan. 2026. "Optimization of Microfluidizer-Produced PLGA Nano-Micelles for Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Efficacy: A Quality by Design Approach" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010025

APA StyleDeveli Arslanhan, E. N., Bahadori, F., Eskandari, Z., Kasapoglu, M. Z., & Mankan, E. (2026). Optimization of Microfluidizer-Produced PLGA Nano-Micelles for Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Efficacy: A Quality by Design Approach. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010025