Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

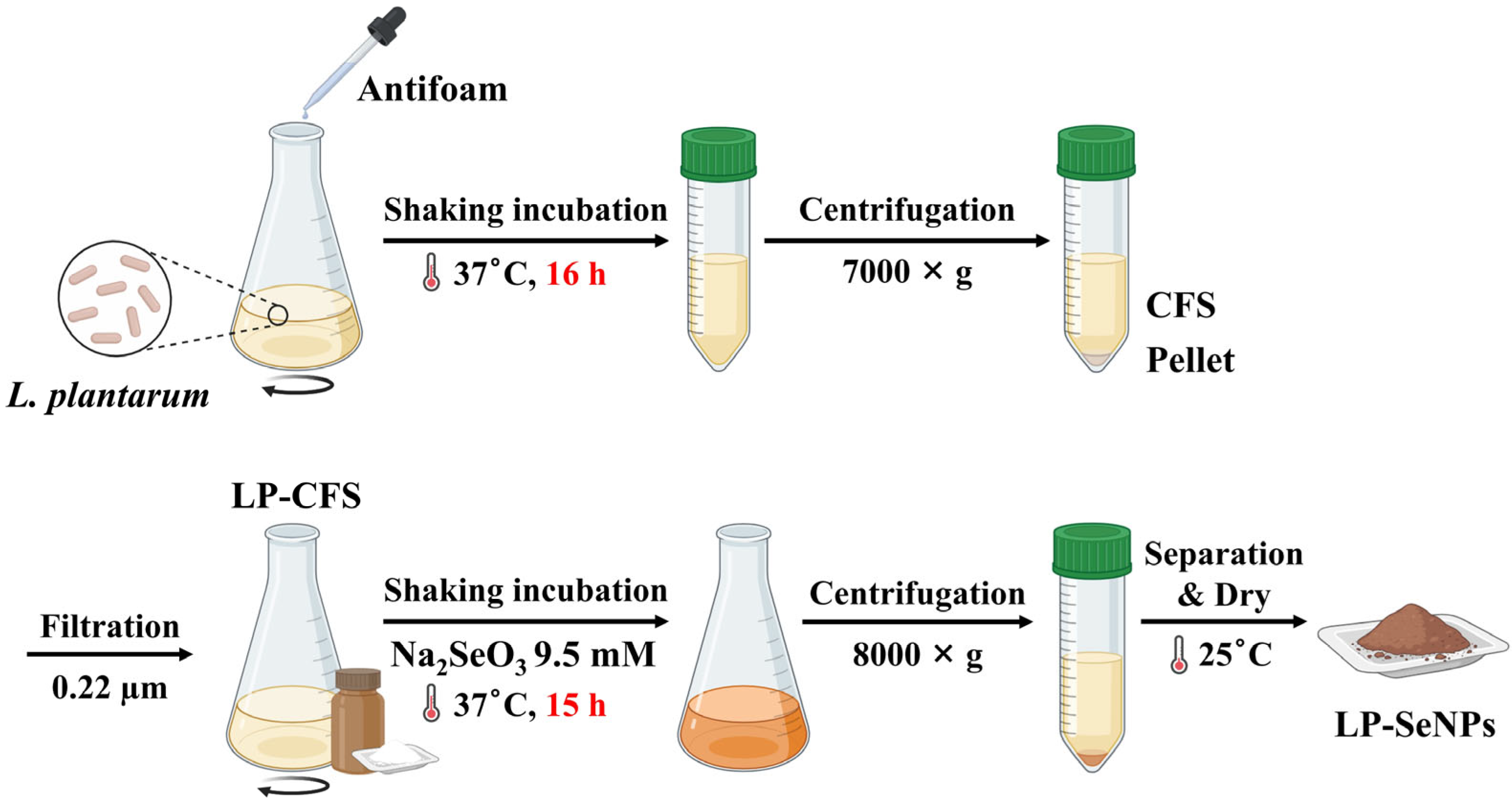

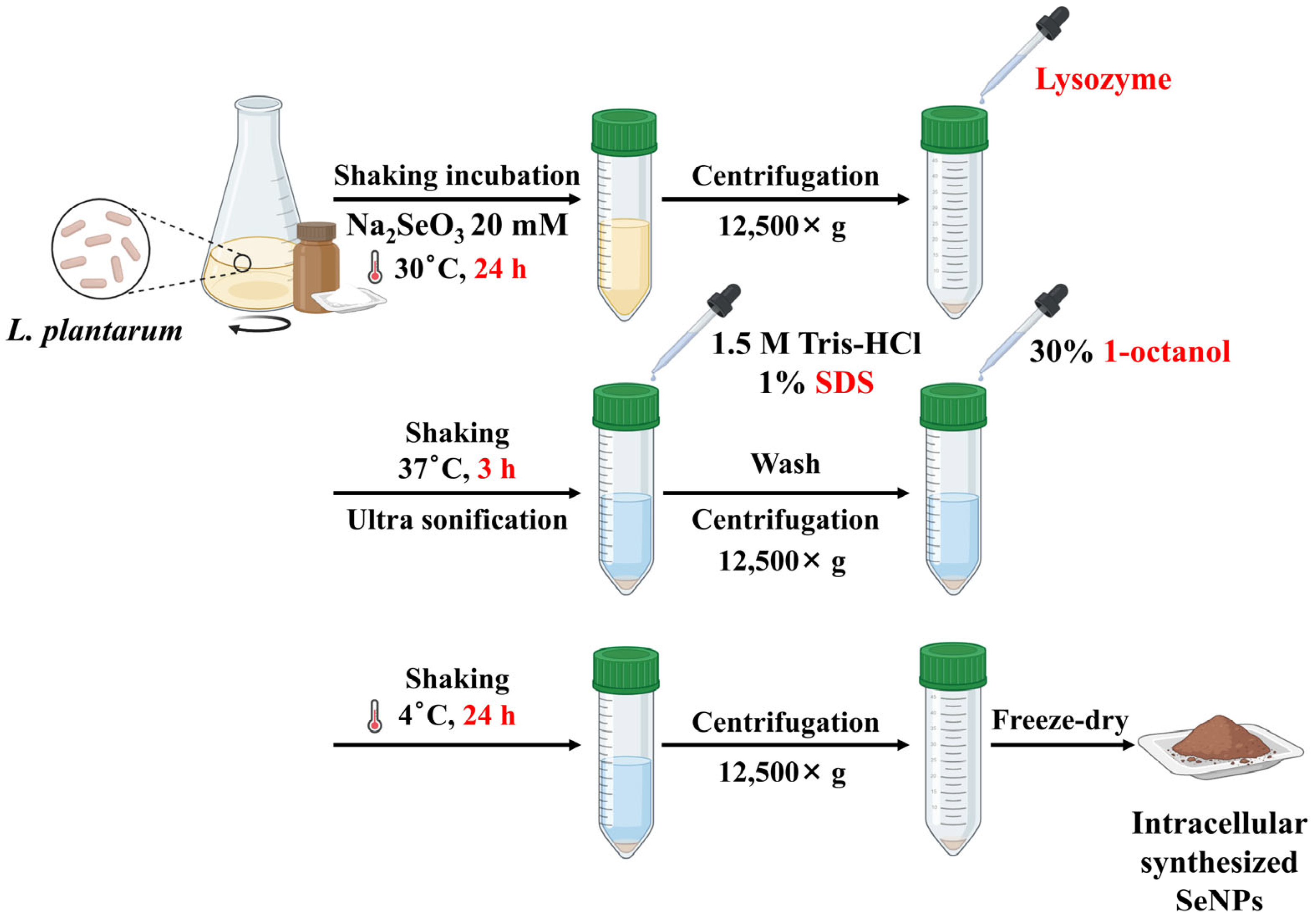

2.2. Synthesis of LP-SeNPs and Chem-SeNPs

2.3. Characterization of LP-SeNPs and Chem-SeNPs

2.4. Analysis of Antibacterial Activity

2.4.1. MIC Determination

2.4.2. Synergy Testing with Conventional Antibiotics

2.4.3. Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Determination

2.4.4. Time-Kill Curve Assays

2.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

2.6. SEM Image Analysis of MRSA

2.7. Quantification of Total Cellular Proteins

2.8. Measurement of ROS Production

2.9. Role of LP-SeNPs–Associated Biomolecules in Antibacterial Activity

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of SeNPs Using LP-CFS

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of LP-SeNPs

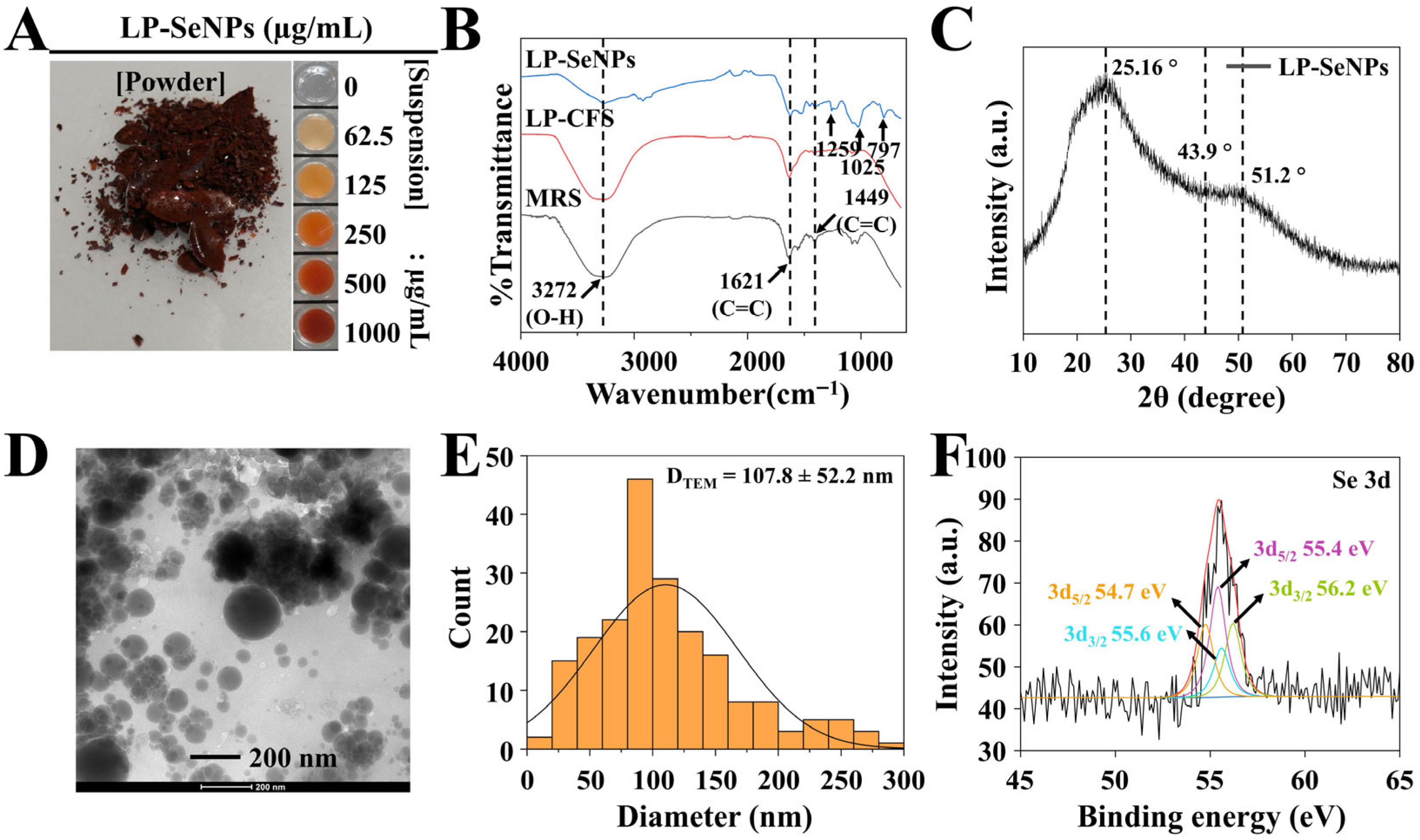

3.2.1. Characterization of LP-SeNPs

FTIR Spectroscopy

XRD Pattern Analysis

TEM Image Analysis

XPS Analysis

Zeta Potential Measurement

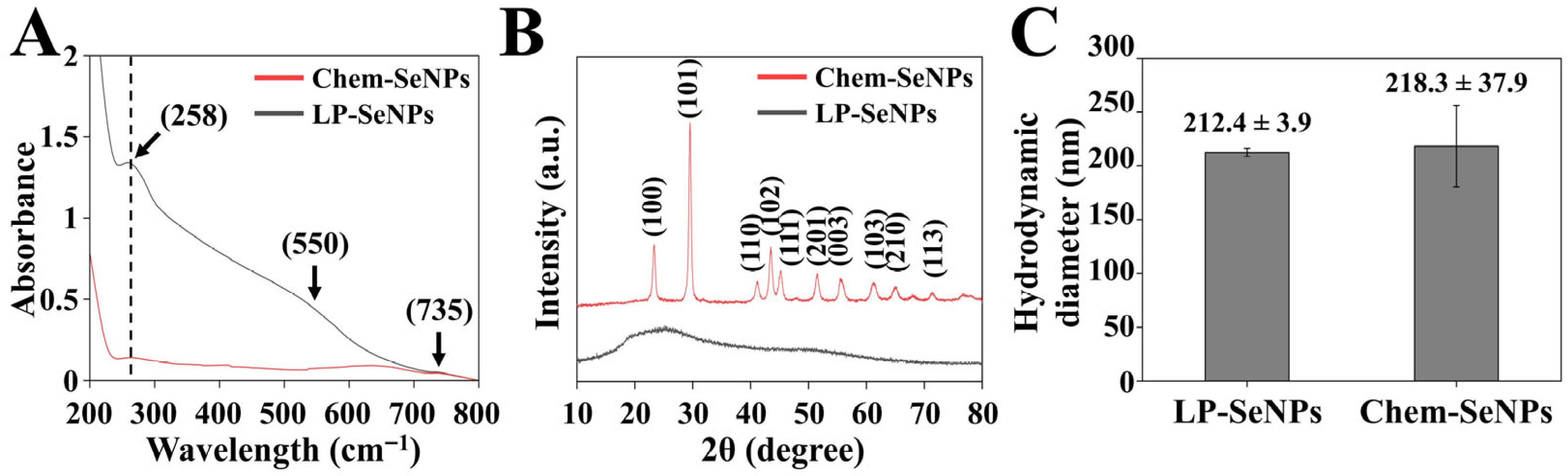

3.2.2. Comparison of Physicochemical Properties of LP-SeNPs and Chem-SeNPs

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Analysis

XRD Analysis

DLS Analysis

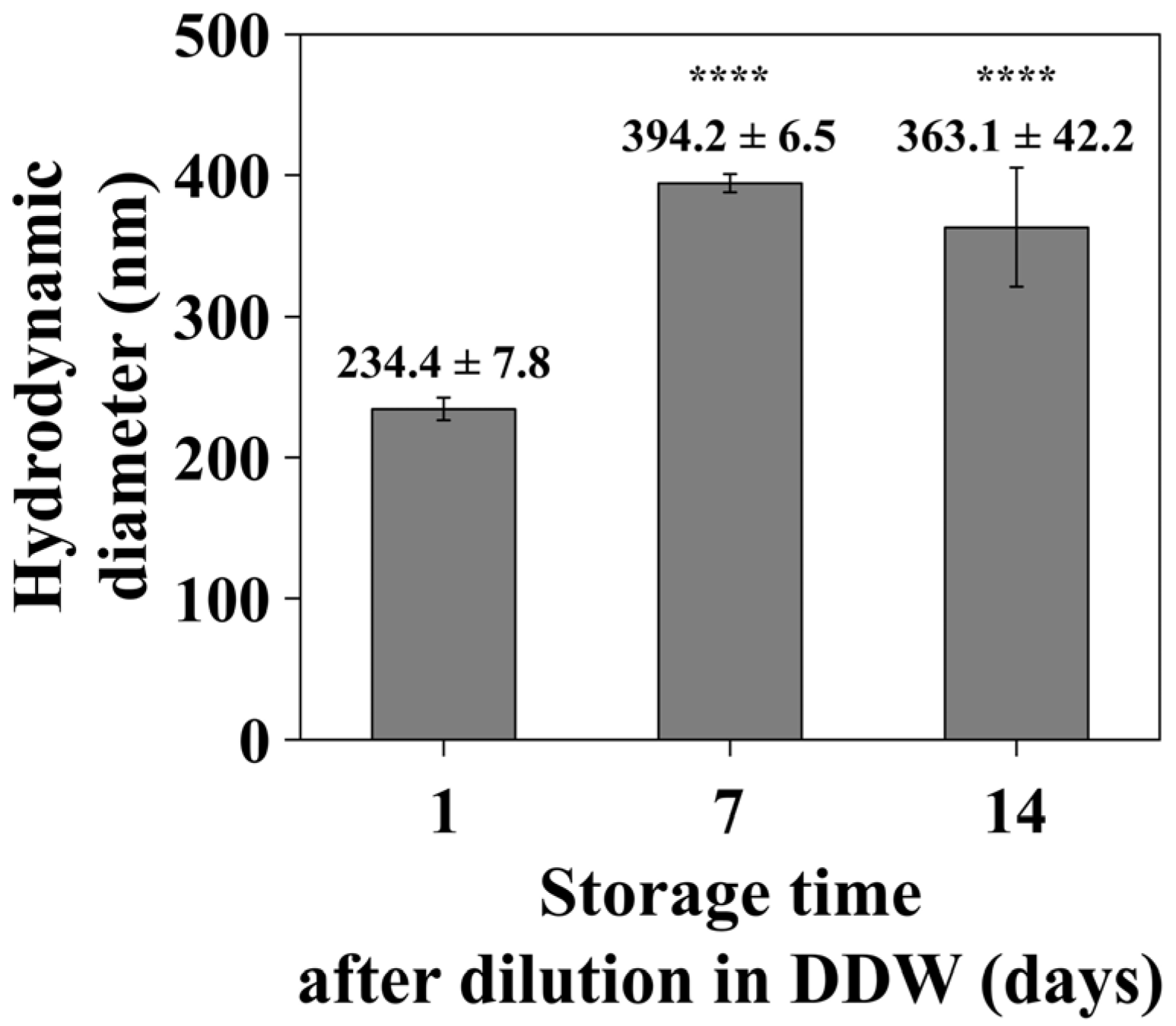

3.2.3. Time-Dependent DLS Analysis

3.3. Antibacterial Potential of LP-SeNPs

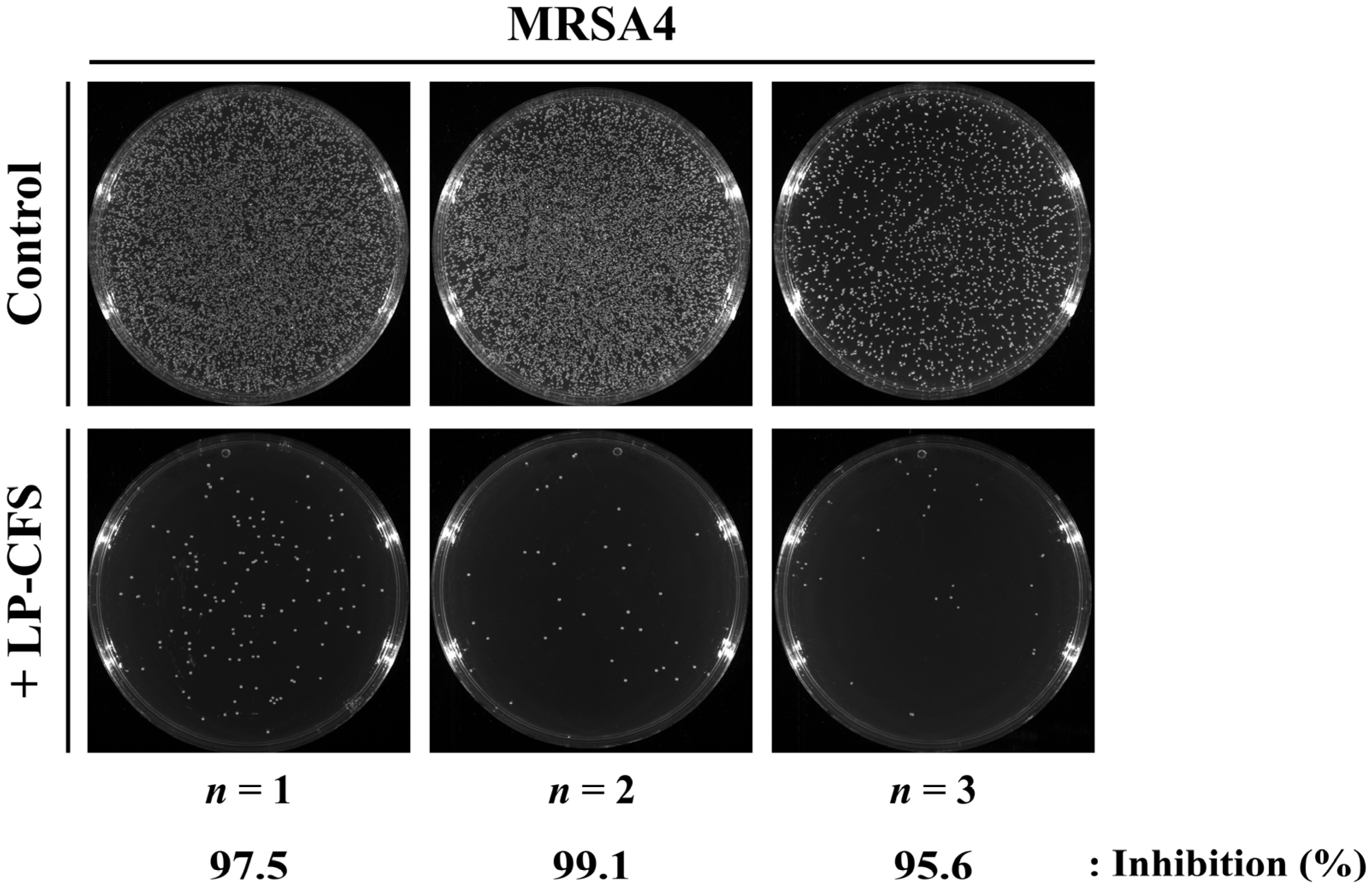

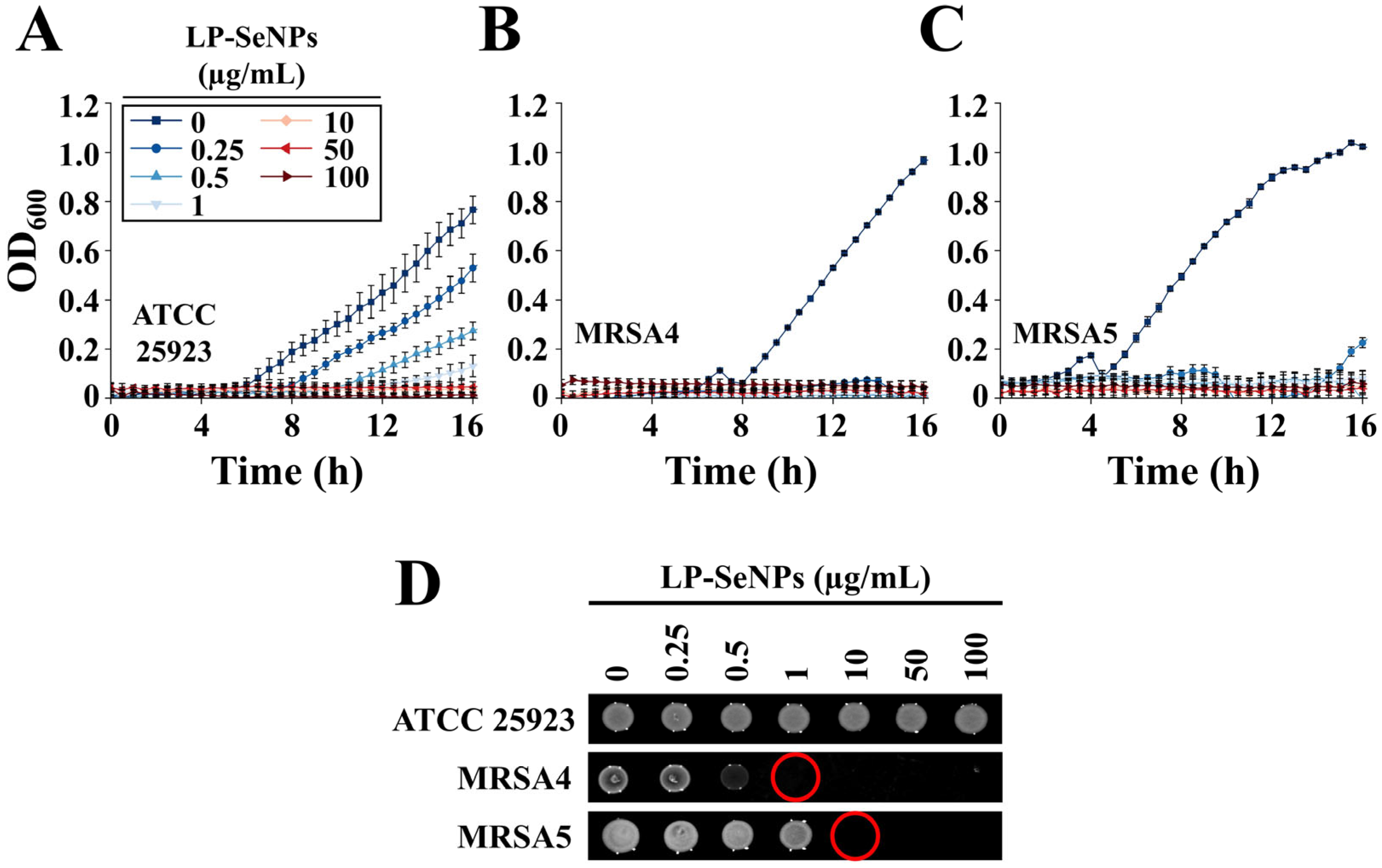

3.3.1. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity of LP-SeNPs

3.3.2. Determination of Bactericidal Activity Using Time–Kill Curve Assays

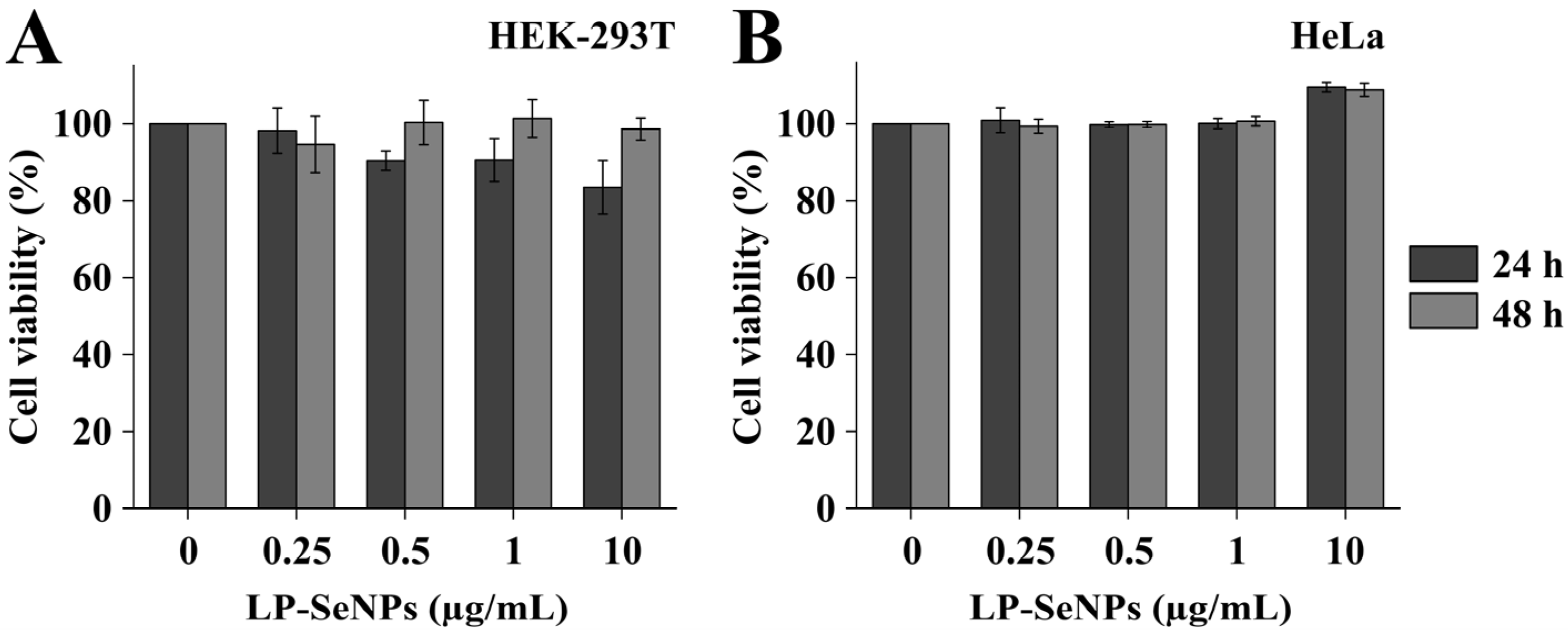

3.4. Cytotoxicity of LP-SeNPs

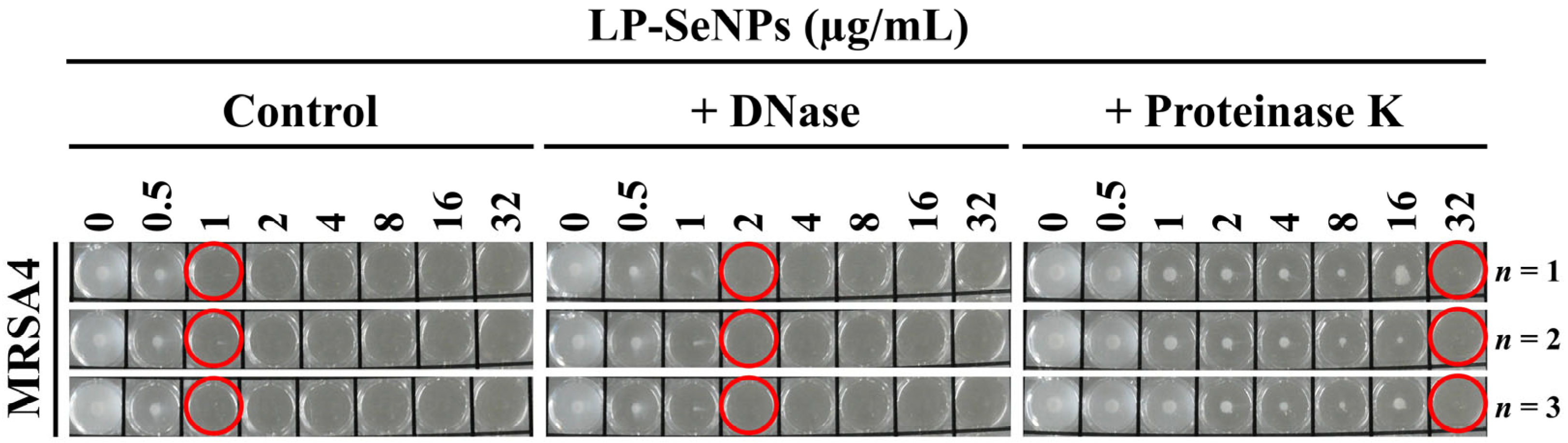

3.5. Assessment of the Role of LP-SeNPs–Associated Biomolecules in Antibacterial Activity

3.6. Antibacterial Mechanisms of LP-SeNPs Against MRSA

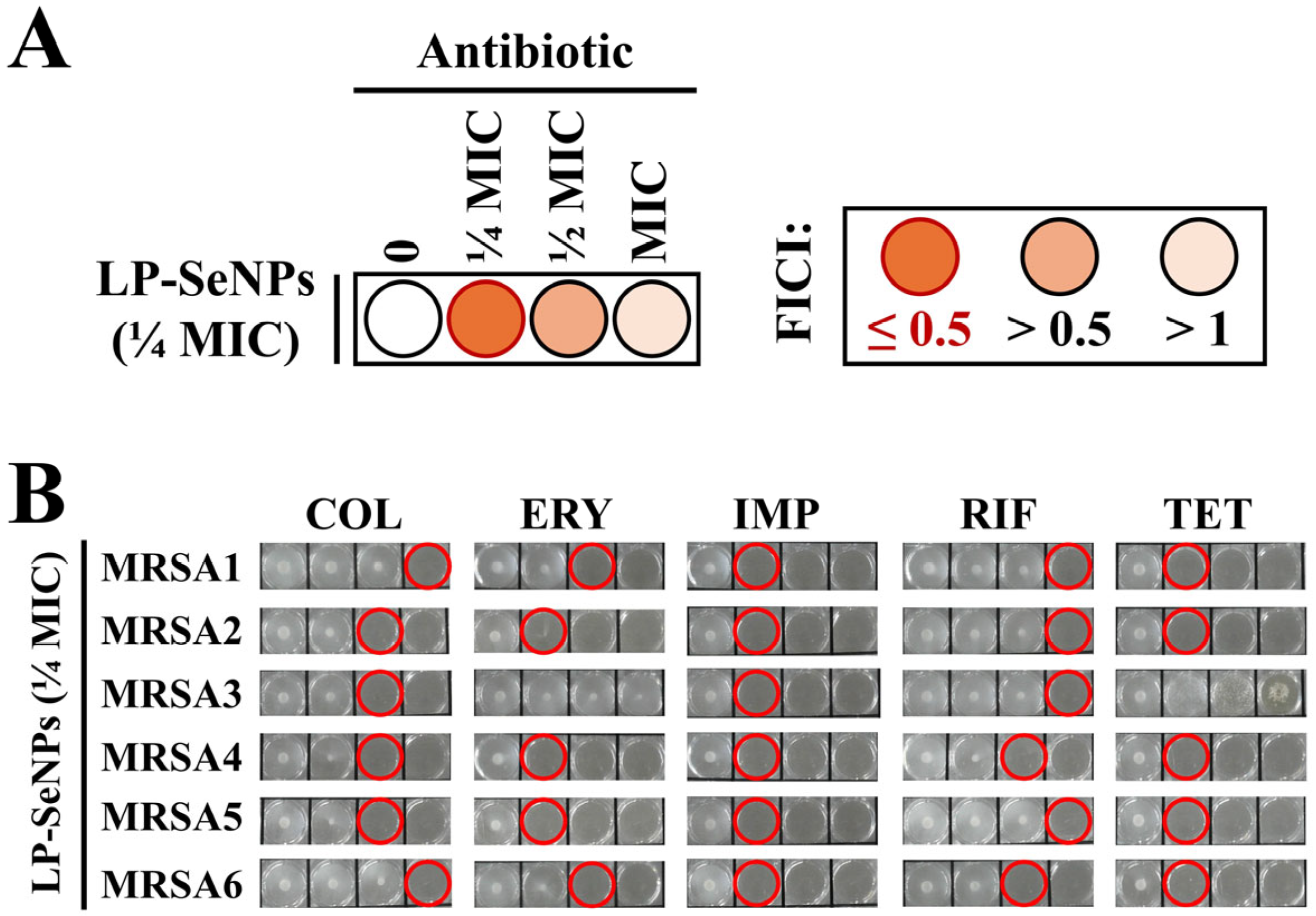

3.6.1. Synergistic Antibiotic Screening

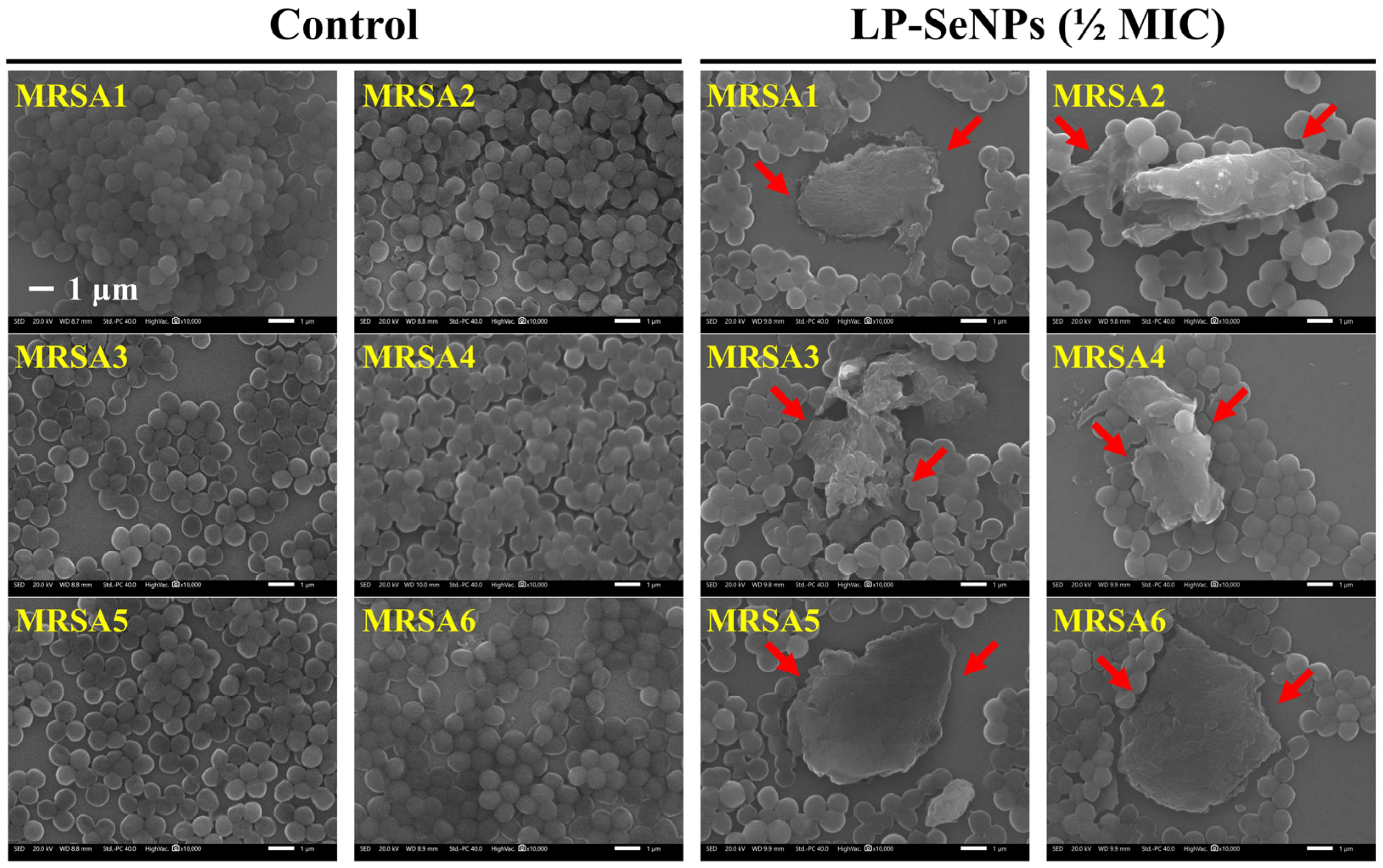

3.6.2. Morphological Characterization of MRSA Cells Treated with LP-SeNPs

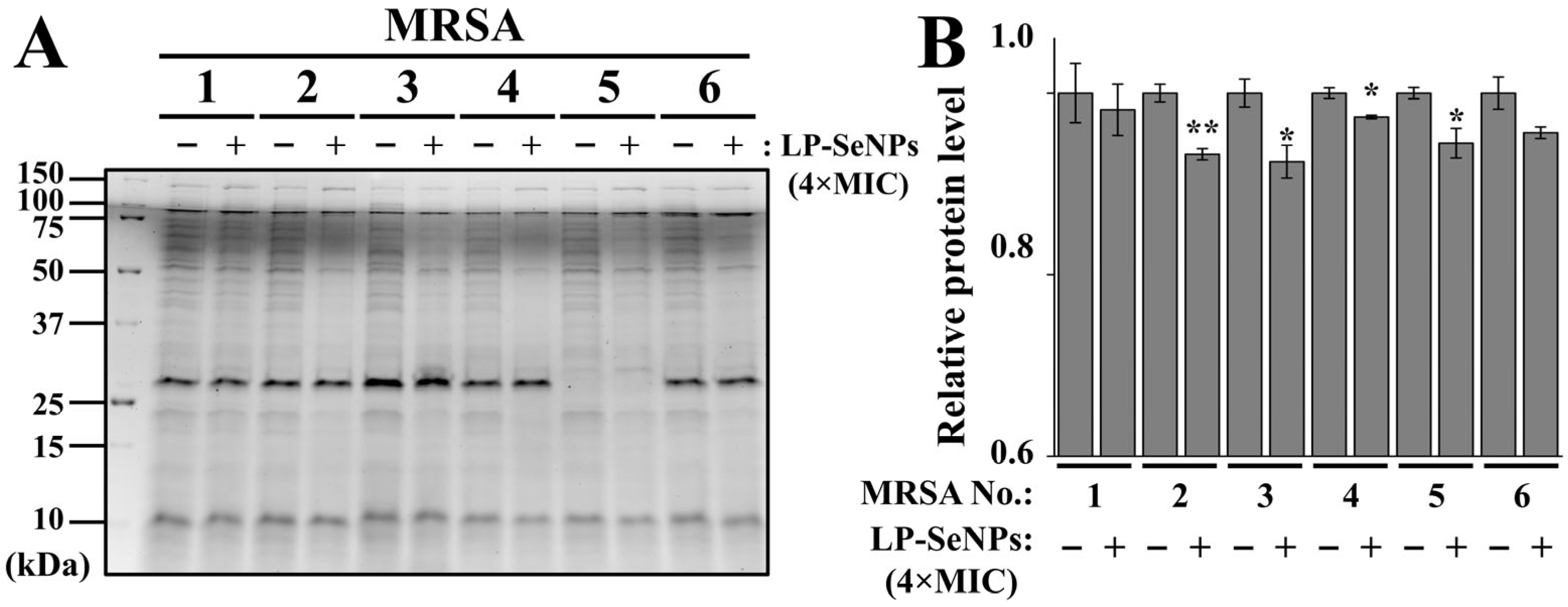

3.6.3. Characterization of Total Cell Proteins in MRSA Treated with LP-SeNPs

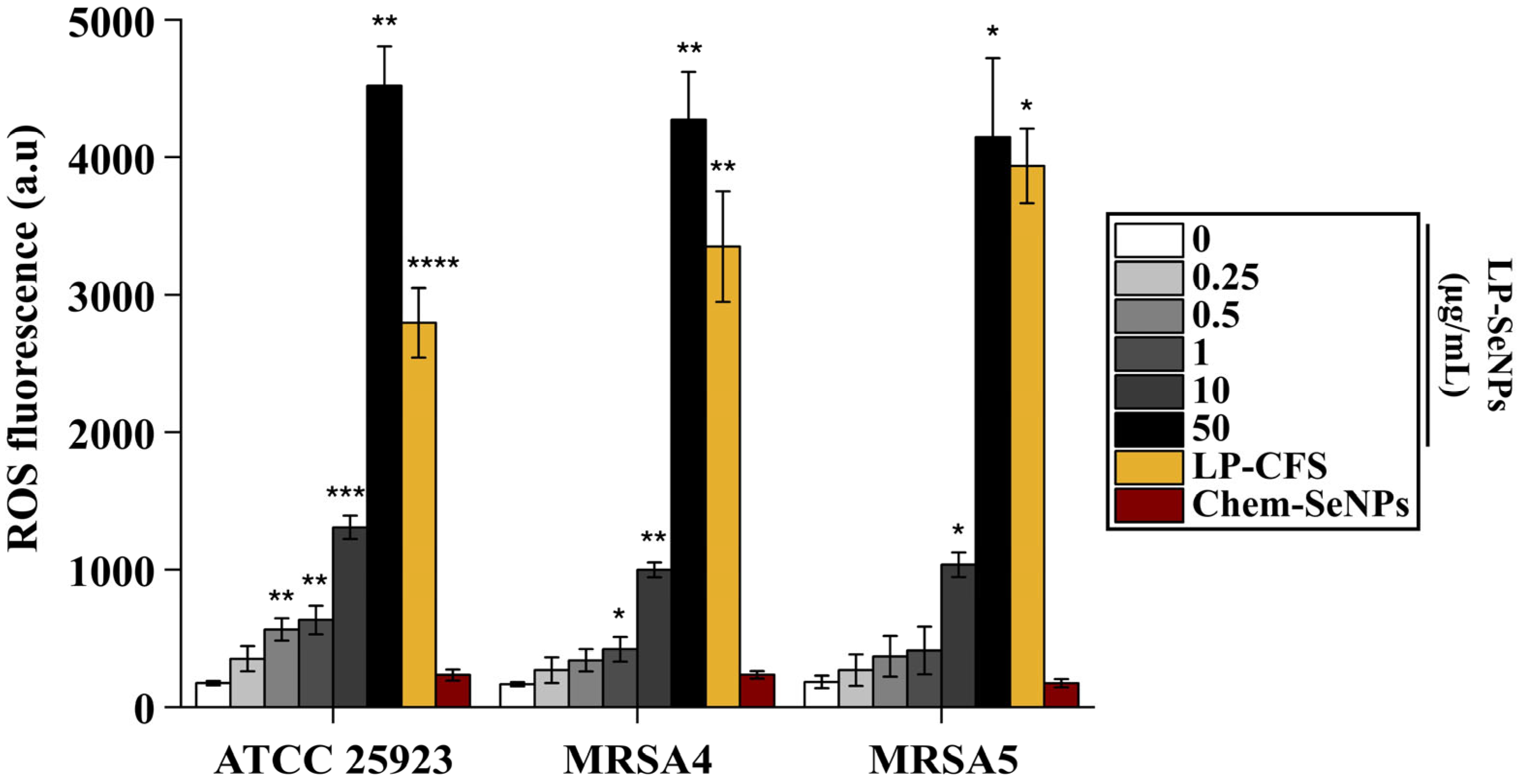

3.6.4. ROS Production Ability of LP-SeNPs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CFS | Cell-Free Supernatant |

| Chem-SeNPs | Chemically synthesized Selenium Nanoparticles |

| COL | Colistin |

| DCFH-DA | 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein Diacetate |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| FICI | Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HEK | Human Embryonic Kidney |

| IMP | Imipenem |

| LP | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum |

| LP-CFS | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-derived Cell Free Supernatant |

| LP-SeNPs | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-derived Selenium Nanoparticles |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NPs | Nanoparticle(s) |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SeNP(s) | Selenium Nanoparticle(s) |

| TET | Tetracycline |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

References

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, T.J. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodi, M.; Ardanuy, C.; Rello, J. Impact of Gram-positive resistance on outcome of nosocomial pneumonia. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, N82–N86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, P.; Kumar, P.; Mickymaray, S.; Alothaim, A.S.; Somasundaram, J.; Rajan, M. Recent Developments in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Treatment: A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.; Calabrese, G.; Guglielmino, S.P.P.; Conoci, S. Metal-Based Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Mechanisms and Biomedical Application. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Synthesis, applications, toxicity and toxicity mechanisms of silver nanoparticles: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 253, 114636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, J.; Vucevic, D.; Radosavljevic, T.; Mandic-Rajcevic, S.; Pantic, I. Iron-based nanoparticles and their potential toxicity: Focus on oxidative stress and apoptosis. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2020, 316, 108935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna, T.; Maldonado-Bravo, F.; Jara, P.; Caro, N. Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaravelu, S.; Motsoene, F.; Abrahamse, H.; Dhilip Kumar, S.S. Green-synthesized metal nanoparticles: A promising approach for accelerated wound healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1637589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Badr, M.M.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; et al. Synthesis of green nanoparticles for energy, biomedical, environmental, agricultural, and food applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y. Essential trace element selenium and redox regulation: Its metabolism, physiological function, and related diseases. Redox Exp. Med. 2022, 2022, R149–R158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, T. Elemental selenium at nano size (Nano-Se) as a potential chemopreventive agent with reduced risk of selenium toxicity: Comparison with se-methylselenocysteine in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 101, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Sachan, K.; Baskar, P.; Saikanth, D.R.K.; Lytand, W.; Kumar, R.K.M.H.; Singh, B.V. Soil Microbes Expertly Balancing Nutrient Demands and Environmental Preservation and Ensuring the Delicate Stability of Our Ecosystems—A Review. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2023, 35, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, W.A.; Batley, G.E.; Krikowa, F.; Ellwood, M.J.; Potts, J.; Swanson, R.; Scanes, P. Selenium cycling in a marine dominated estuary: Lake Macquarie, NSW, Australia a case study. Environ. Chem. 2022, 19, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.; Phalswal, P.; Khanna, P.K. Selenium nanoparticles: A review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 1415–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes Filho, S.; Dos Santos, M.S.; Dos Santos, O.A.L.; Backx, B.P.; Soran, M.L.; Opris, O.; Lung, I.; Stegarescu, A.; Bououdina, M. Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts and Essential Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.B.; Samanta, D. Engineering protein-based therapeutics through structural and chemical design. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Dou, X.; Song, X.; Xu, C. Green synthesis of nanoparticles by probiotics and their application. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 119, 83–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K.; Sharma, M.; Parul; Raut, S.; Gupta, P.; Khatri, N. Healing wounds, defeating biofilms: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in tackling MRSA infections. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1284195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.G.; Moreno-Martin, G.; Pescuma, M.; Madrid-Albarran, Y.; Mozzi, F. Biotransformation of Selenium by Lactic Acid Bacteria: Formation of Seleno-Nanoparticles and Seleno-Amino Acids. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Xu, W.; Xie, H.; Wu, Z. Biosynthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles by Se-tolerant Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Magar, K.B.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.R. Design, synthesis, and discovery of novel oxindoles bearing 3-heterocycles as species-specific and combinatorial agents in eradicating Staphylococcus species. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, M.; Tohidi Moghadam, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Selenium Nanoparticles-Lysozyme Nanohybrid System with Synergistic Antibacterial Properties. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacenza, E.; Sule, K.; Presentato, A.; Wells, F.; Turner, R.J.; Prenner, E.J. Impact of Biogenic and Chemogenic Selenium Nanoparticles on Model Eukaryotic Lipid Membranes. Langmuir 2023, 39, 10406–10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Ochi, A.; Mihara, H.; Ogra, Y. Comparison of Nutritional Availability of Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles and Chemically Synthesized Selenium Nanoparticles. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 4861–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naskar, A.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.S. A MoS(2) based silver-doped ZnO nanocomposite and its antibacterial activity against beta-lactamase expressing Escherichia coli. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 7268–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Singh, D.; Arif, A.; Sodhi, K.K.; Singh, D.K.; Islam, S.N.; Ahmad, A.; Akhtar, K.; Siddique, H.R. Protective effect of green synthesized Selenium Nanoparticles against Doxorubicin induced multiple adverse effects in Swiss albino mice. Life Sci. 2022, 305, 120792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, T.; Pan, J.G. In vitro evaluation of ciclopirox as an adjuvant for polymyxin B against gram-negative bacteria. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul Selvaraj, R.C.; Rajendran, M.; Nagaiah, H.P. Re-Potentiation of beta-Lactam Antibiotic by Synergistic Combination with Biogenic Copper Oxide Nanocubes against Biofilm Forming Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Molecules 2019, 24, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, H.; Kim, K.-S. Surface-displaying protein from Lacticaseibacillus paracasei–derived extracellular vesicles: Identification and utilization in the fabrication of an endolysin-displaying platform against Staphylococcus aureus. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, A.; Cho, H.; Kim, K.-S. Black Phosphorus-Based ZnO-Ag Nanocomposite for Antibacterial Activity against Tigecycline-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP); Lambre, C.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; Lampi, E.; Mengelers, M.; et al. Safety evaluation of the food enzyme lysozyme from hens’ eggs. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e07916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Adem, K.; Lukman, S.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, S. Inhibition of lysozyme aggregation and cellular toxicity by organic acids at acidic and physiological pH conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, V.V. The mechanism of hemolysis of erythrocytes by sodium dodecyl sulfate. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1048, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintubin, L.; De Windt, W.; Dick, J.; Mast, J.; van der Ha, D.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Lactic acid bacteria as reducing and capping agent for the fast and efficient production of silver nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabnikova, O.; Khonkiv, M.; Kovshar, I.; Stabnikov, V. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by lactic acid bacteria and areas of their possible applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Voorde, I.; Goiris, K.; Syryn, E.; Van den Bussche, C.; Aerts, G. Evaluation of the cold-active Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis β-galactosidase enzyme for lactose hydrolysis in whey permeate as primary step of d-tagatose production. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 2134–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Onaolapo, A.O.; Ibaba, A.L. Cell free supernatant for sustainable crop production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1549048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswin, H.P.; Haddrell, A.E.; Hughes, C.; Otero-Fernandez, M.; Thomas, R.J.; Reid, J.P. Oxidative Stress Contributes to Bacterial Airborne Loss of Viability. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0334722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahabadi, N.; Zendehcheshm, S.; Khademi, F. Selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, in-vitro cytotoxicity, antioxidant activity and interaction studies with ct-DNA and HSA, HHb and Cyt c serum proteins. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Quwaie, D.A. The influence of bacterial selenium nanoparticles biosynthesized by Bacillus subtilus DA20 on blood constituents, growth performance, carcass traits, and gut microbiota of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, N.; Abu-Elghait, M.; Gebreel, H.; Zendo, T.; Youssef, H. Lactic Acid Bacteria-Mediated Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles: A Smart Strategy Against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.M.d.S.; Dibo, M.; Sarmiento, J.J.P.; Seabra, A.B.; Medeiros, L.P.; Lourenço, I.M.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Nakazato, G. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using combinations of plant extracts and their antibacterial activity. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, B.; Lv, J.; Yang, H.; He, F.; Hu, Y.; Hu, B.; Jiang, H.; Huo, X.; Tu, J.; Xia, X. Moringa oleifera extract mediated the synthesis of Bio-SeNPs with antibacterial activity against Listeria monocytogenes and Corynebacterium diphtheriae. LWT 2022, 165, 113751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugarova, A.V.; Mamchenkova, P.V.; Dyatlova, Y.A.; Kamnev, A.A. FTIR and Raman spectroscopic studies of selenium nanoparticles synthesised by the bacterium Azospirillum thiophilum. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 192, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, H.; Khatoon, N.; Khan, M.A.; Husain, S.A.; Saravanan, M.; Sardar, M. Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Probiotic Bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus and Their Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity Against Resistant Bacteria. J. Clust. Sci. 2020, 31, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Mohite, P.; Patil, S.; Chidrawar, V.R.; Ushir, Y.V.; Dodiya, R.; Singh, S. Facile green synthesis and characterization of Terminalia arjuna bark phenolic-selenium nanogel: A biocompatible and green nano-biomaterial for multifaceted biological applications. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1273360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar-Acar, B. Size reduction of selenium nanoparticles synthesized from yeast beta glucan using cold atmospheric plasma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, P.T.; Pham, N.H.; Le, T.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Do, D.T.; La, D.D. Green Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Cleistocalyx operculatus Leaf Extract and Their Acute Oral Toxicity Study. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Abou-ElWafa, G.S.; Aldesuquy, H.S.; Eltanahy, E. Bioactivity of selenium nanoparticles biosynthesized by crude phycocyanin extract of Leptolyngbya sp. SSI24 cultivated on recycled filter cake wastes from sugar-industry. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sans-Serramitjana, E.; Gallardo-Benavente, C.; Melo, F.; Perez-Donoso, J.M.; Rumpel, C.; Barra, P.J.; Duran, P.; Mora, M.L. A Comparative Study of the Synthesis and Characterization of Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles by Two Contrasting Endophytic Selenobacteria. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Hower, J.C.; Dai, S.; Mardon, S.M.; Liu, G. Determination of Chemical Speciation of Arsenic and Selenium in High-As Coal Combustion Ash by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Examples from a Kentucky Stoker Ash. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 17637–17645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthakumar, S.; Manikandan, M.; Arumugam, M. Green synthesis, characterization and functional validation of bio-transformed selenium nanoparticles. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, H.; Weser, U. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of some selenium containing amino acids. Bioinorg. Chem. 1975, 5, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, N.; Atieh, M.A.; Koç, M. A comprehensive review on synthesis, stability, thermophysical properties, and characterization of nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2019, 344, 404–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, C.P.; Zhung, C.M.; Shih, Y.H.; Tseng, Y.M.; Wu, S.C.; Doong, R.A. Stability of metal oxide nanoparticles in aqueous solutions. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J.; Chen, L.; Li, B.; Lin, X. Construction, characterization, and bioactive evaluation of nano-selenium stabilized by green tea nano-aggregates. LWT 2020, 129, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, S.; Hajihajikolai, D.; Ghazale, F.; Gharahdaghigharahtappeh, F.; Faghih, A.; Ahmadi, O.; Behbudi, G. Optimization of Green Synthesis Formulation of Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) Using Peach Tree Leaf Extract and Investigating its Properties and Stability. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 22, e3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.-H.; Chris Wang, C.R. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 92, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card No. 06-0362; Powder Diffraction File (PDF). International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newtown Square, PA, USA.

- Fischer, K.; Schmidt, M. Pitfalls and novel applications of particle sizing by dynamic light scattering. Biomaterials 2016, 98, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, H.; Yang, R.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J. Aggregation and stability of selenium nanoparticles: Complex roles of surface coating, electrolytes and natural organic matter. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 130, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layus, B.; Gerez, C.; Rodriguez, A. Antibacterial Activity of Lactobacillus plantarum CRL 759 Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 4503–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Taha, T.F.; Najjar, A.A.; Zabermawi, N.M.; Nader, M.M.; AbuQamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Salama, A. Selenium nanoparticles from Lactobacillus paracasei HM1 capable of antagonizing animal pathogenic fungi as a new source from human breast milk. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 6782–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo-Tayo, B.; Yusuf, B.; Alao, S. Antibacterial Activity of Intracellular Greenly Fabricated Selenium Nanoparticle of Lactobacillus pentosus ADET MW861694 against Selected Food Pathogens. Int. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 10, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Shen, Z.; Yin, W.; Lemiasheuski, V.; Xu, S.; He, J. Effects of selenium nanoparticles produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus HN23 on lipid deposition in WRL68 cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 145, 107165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhydzetski, A.; Glowacka-Grzyb, Z.; Bukowski, M.; Zadlo, T.; Bonar, E.; Wladyka, B. Agents Targeting the Bacterial Cell Wall as Tools to Combat Gram-Positive Pathogens. Molecules 2024, 29, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Holden, J.A.; Heath, D.E.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; O’Connor, A.J. Engineering highly effective antimicrobial selenium nanoparticles through control of particle size. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 14937–14951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, N.; Usjak, D.; Milenkovic, M.T.; Zheng, K.; Liverani, L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Stevanovic, M.M. Comparative Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles With Different Surface Chemistry and Structure. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 624621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, R.A.; Lahiri, S.D. Narrow-Spectrum Antibacterial Agents-Benefits and Challenges. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lu, C.; Tang, M.; Yang, Z.; Jia, W.; Ma, Y.; Jia, P.; Pei, D.; Wang, H. Nanotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles on HEK293T Cells: A Combined Study Using Biomechanical and Biological Techniques. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6770–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Miao, J.; Zhao, D.; Sun, K.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, W.; et al. Construction of Selenium Nanoparticle-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Potential Antioxidant and Antitumor Activities as a Selenium Supplement. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44851–44860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, E.; Bochicchio, D.; Gasbarri, M.; Odino, D.; Canale, C.; Ferrando, R.; Canepa, F.; Stellacci, F.; Rossi, G.; Dante, S.; et al. Cholesterol Hinders the Passive Uptake of Amphiphilic Nanoparticles into Fluid Lipid Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 8583–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 5577–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, A.; Tang, P.S.; Chan, W.C. The effect of nanoparticle size, shape, and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Poonia, A.K.; Yadav, D.; Jin, J.O. Microbe-Mediated Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles: Applications and Future Prospects. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savvidou, M.G.; Kontari, E.; Kalantzi, S.; Mamma, D. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Cell-Free Supernatant of Haematococcus pluvialis Culture. Materials 2023, 17, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunoh, T.; Takeda, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Suzuki, I.; Takano, M.; Kunoh, H.; Takada, J. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Coupled with Nucleic Acid Oxidation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, G.; Saigal, S.; Elongavan, A. Action and resistance mechanisms of antibiotics: A guide for clinicians. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 33, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, T.; Ishino, F.; Nakagawa, J.; Tamaki, S.; Matsuhashi, M. Studies on the mechanism of action of imipenem (N-formimidoylthienamycin) in vitro: Binding to the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and inhibition of enzyme activities due to the PBPs in E. coli. J. Antibiot. 1984, 37, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Dai, C.; Wang, P.; Fan, S.; Yu, B.; Qu, Y. Antibacterial properties and mechanism of selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Providencia sp. DCX. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douthwaite, S.; Aagaard, C. Erythromycin binding is reduced in ribosomes with conformational alterations in the 23 S rRNA peptidyl transferase loop. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 232, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Z.; Lomakin, I.B.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Bunick, C.G. Sarecycline interferes with tRNA accommodation and tethers mRNA to the 70S ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 20530–20537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Lou, H.; Wei, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q. Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of ultrasound and MEL-A against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, S.J.; Lesniczak-Staszak, M.; Gowin, E.; Szaflarski, W. Mechanistic Insights into Clinically Relevant Ribosome-Targeting Antibiotics. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoq, B.-E.; Britel, M.; Bouajaj, A.; Maalej, R.; Touhami, A.; Abid, M.; Douiri, H.; Touhami, F.; Maurady, A. A Review on Antibacterial Activity of Nanoparticles. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | 1 Strain Identification Number | MIC (µg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chem- SeNPs | LP- SeNPs | ||

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 | >100 | >100 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | NCCP 16285 | >100 | >100 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | ATCC 19606 | >100 | >100 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | >100 | >100 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 25923 | >100 | 50 |

| 2 Clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant S. aureus | MRSA1 | >100 | 0.5 |

| MRSA2 | >100 | 1 | |

| MRSA3 | >100 | 1 | |

| MRSA4 | >100 | 0.5 | |

| MRSA5 | >100 | 0.5 | |

| MRSA6 | >100 | 1 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | ATCC 14990 | >100 | 50 |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | ATCC 15305 | >100 | 8 |

| Antibiotic | Mechanism of Action | Cellular Target | MIC (µg/mL) Against MRSA Strains (-LP-SeNPs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| COL | Cell membrane disruption | LPS binding | 64 | 64 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 32 |

| ERY | Protein synthesis inhibition | 50 S ribosome binding | 1 | 1 | >100 | 2 | >100 | 1 |

| IMP | Cell wall synthesis inhibition | PBP binding | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| RIF | Nucleic acid synthesis inhibition | DNA dependent RNA polymerase target | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| TET | Protein synthesis inhibition | 30 S ribosome binding | 1 | 0.5 | >100 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Antibiotic | MIC Against MRSA Strains (+LP-SeNPs) (µg/mL) | Synergy Phenotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| COL | 64 | 2 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | No synergy |

| ERY | 0.5 | 0.25 | >100 | 0.5 | 25 | 0.5 | Isolates dependent synergy |

| IMP | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | Synergy |

| RIF | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | No synergy |

| TET | 0.25 | 0.13 | >100 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.5 | Isolates dependent synergy |

| Parameter | Intracellular Synthesis [22] | LP-SeNPs (This Study) |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis strategy | Intracellular biotransformation within bacterial cells | Extracellular, CFS-mediated biogenic reduction |

| Production mechanism | Enzyme-mediated intracellular reduction during growth | Enzyme- and peptide-mediated extracellular reduction in CFS [21] |

| Cell Lysis reagents (Enzyme or chemicals) | Requires lysozyme, SDS, or 1-octanol | Not required |

| Purification steps | Multi-steps: cell lysis, centrifugation and solvent extraction | Single step: centrifugation |

| Localization of SeNPs | Intracellular; associated with cytoplasmic debris | Extracellular, freely suspended in CFS |

| Yield | Not quantified; low recovery | ~7 µg/mL of CFS |

| Antibacterial activity | Low | High |

| Target species | S. aureus and E. coli (non-specific) | MRSA (specific) |

| Mechanistic insight | Not characterized | Cell wall disruption (Major) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, G.-m.; Oh, S.; Kim, K.-s. Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010014

Kim G-m, Oh S, Kim K-s. Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gyeong-min, SeCheol Oh, and Kwang-sun Kim. 2026. "Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010014

APA StyleKim, G.-m., Oh, S., & Kim, K.-s. (2026). Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010014