Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosoglutathione-Conjugated TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose Hydrogel for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of GSNO

2.3. Preparation of NC-GSNO

2.4. Loading of NC-GSNO

2.5. Characterization of NC-GSNO

2.6. Gelation and Water Uptake

2.7. GSNO Leakage

2.8. NO Release of NC-GSNO

2.9. In Vitro Antibacterial Study

2.10. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Study

2.11. In Vitro Cell Migration Study

2.12. MRSA-Infected Wound Model

2.13. In Vivo Wound Healing Study

2.14. Histology

2.15. Statistics

3. Results

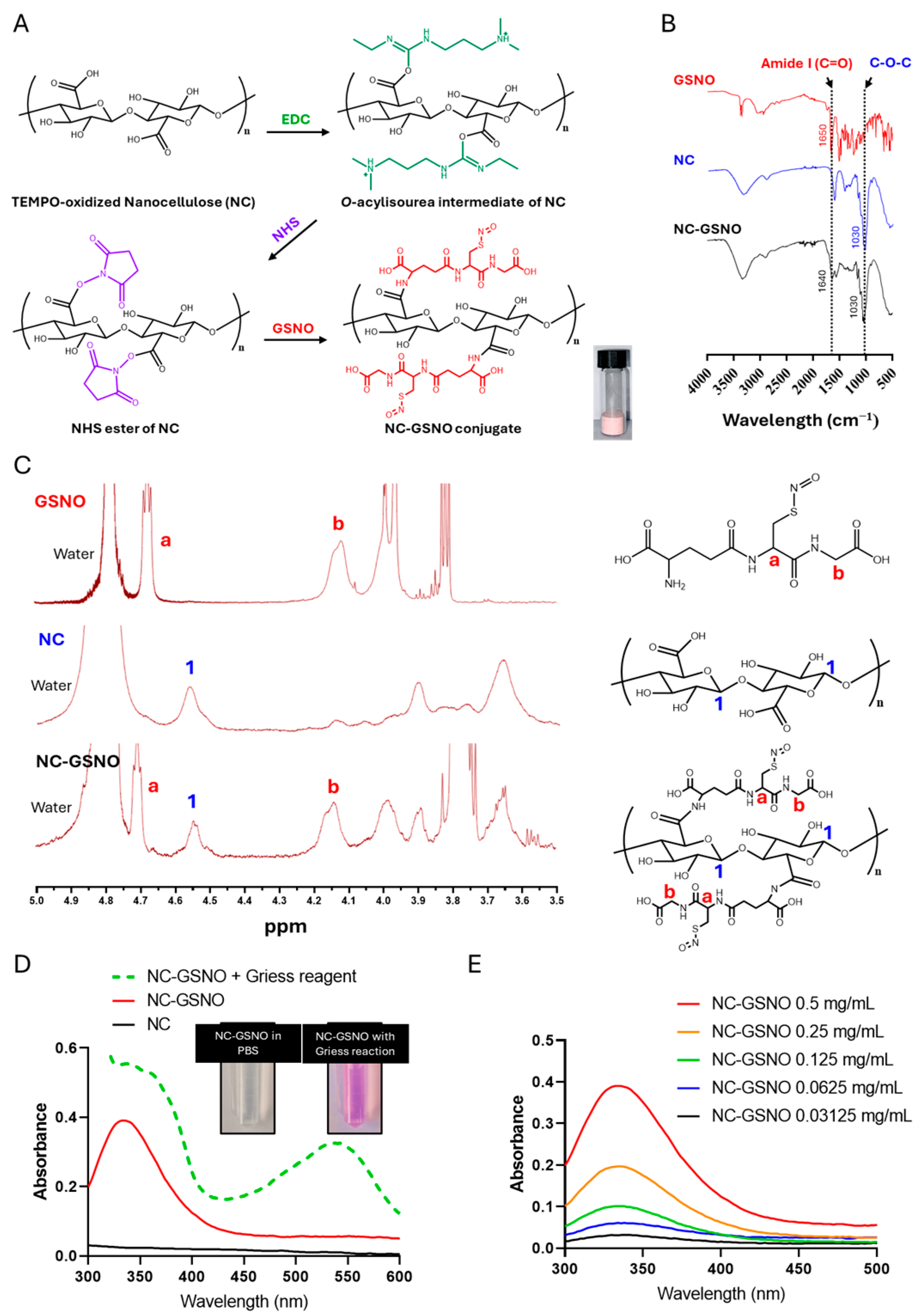

3.1. Characterization of NC-GSNO

3.2. Hydrogel Properties of NC-GSNO

3.3. GSNO Leakage and NO Release Study

3.4. In Vitro Antibacterial Study

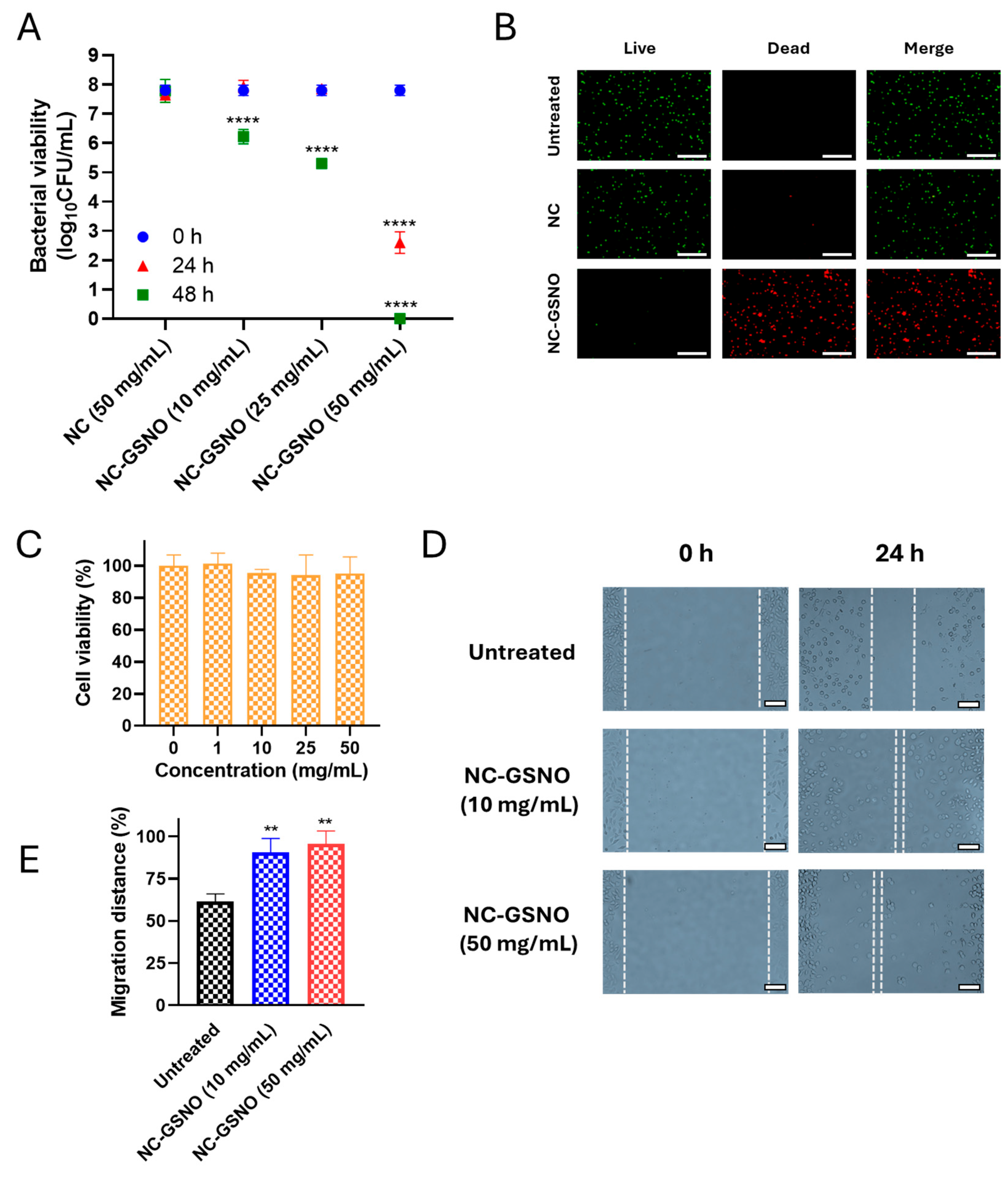

3.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Study

3.6. In Vitro Cell Migration Study

3.7. In Vivo Wound Healing Study

3.8. Histology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linz, M.S.; Mattappallil, A.; Finkel, D.; Parker, D. Clinical impact of Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, M.; Aqib, A.I.; Muzammil, I.; Majeed, N.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Kulyar, M.F.-e.-A.; Fatima, M.; Zaheer, C.-N.F.; Muneer, A.; Murtaza, M.; et al. MRSA compendium of epidemiology, transmission, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention within one health framework. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1067284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Factors affecting wound healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer-Geissler, J.C.; Schwingenschuh, S.; Zacharias, M.; Einsiedler, J.; Kainz, S.; Reisenegger, P.; Holecek, C.; Hofmann, E.; Wolff-Winiski, B.; Fahrngruber, H.; et al. The impact of prolonged inflammation on wound healing. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardins-Park, H.E.; Gurtner, G.C.; Wan, D.C.; Longaker, M.T. From chronic wounds to scarring: The growing health care burden of under-and over-healing wounds. Adv. Wound Care 2022, 11, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.; Liu, P.Y.; Schultz, G.S.; Martins-Green, M.M.; Tanaka, R.; Weir, D.; Gould, L.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Gibbons, G.W.; Wolcott, R.; et al. Chronic wounds: Treatment consensus. Wound Repair Regen. 2022, 30, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howden, B.P.; Davies, J.K.; Johnson, P.D.; Stinear, T.P.; Grayson, M.L. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: Resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 99–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, M.A.; Fang, F.C. NO inhibitions: Antimicrobial properties of nitric oxide. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, S162–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okda, M.; Spina, S.; Fakhr, B.S.; Carroll, R.W. The antimicrobial effects of nitric oxide: A narrative review. Nitric Oxide 2025, 155, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.K.; Picciotti, S.L.; Duke, M.M.; Broberg, C.A.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric oxide-induced morphological changes to bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Kashfi, K.; Ghasemi, A. Nitric oxide-based treatments improve wound healing associated with diabetes mellitus. Med. Gas Res. 2025, 15, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.-d.; Chen, A.F. Nitric oxide: A newly discovered function on wound healing. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, L.-L. Advanced nitric oxide donors: Chemical structure of NO drugs, NO nanomedicines and biomedical applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broniowska, K.A.; Diers, A.R.; Hogg, N. S-nitrosoglutathione. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3173–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Ye, Z.; Pi, L.; Ao, J. Roles and current applications of S-nitrosoglutathione in anti-infective biomaterials. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 16, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, W.H.; Rice, S.A. Recent developments in nitric oxide donors and delivery for antimicrobial and anti-biofilm applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.; Boudier, A.; Perrin, J.; Vigneron, C.; Maincent, P.; Violle, N.; Bisson, J.-F.; Lartaud, I.; Dupuis, F. In situ microparticles loaded with S-nitrosoglutathione protect from stroke. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Zhang, K.; Ge, S.; Shi, Y.; Du, C.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L. A mini review of S-nitrosoglutathione loaded nano/micro-formulation strategies. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hlaing, S.P.; Cao, J.; Hasan, N.; Ahn, H.-J.; Song, K.-W.; Yoo, J.-W. In situ hydrogel-forming/nitric oxide-releasing wound dressing for enhanced antibacterial activity and healing in mice with infected wounds. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.O.; Noh, J.-K.; Thapa, R.K.; Hasan, N.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Ku, S.K.; Yoo, J.-W. Nitric oxide-releasing chitosan film for enhanced antibacterial and in vivo wound-healing efficacy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palungan, J.; Luthfiyah, W.; Mustopa, A.Z.; Nurfatwa, M.; Rahman, L.; Yulianty, R.; Wathoni, N.; Yoo, J.-W.; Hasan, N. The formulation and characterization of wound dressing releasing S-nitrosoglutathione from polyvinyl alcohol/borax reinforced carboxymethyl chitosan self-healing hydrogel. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Wen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fang, M.; Xiang, J.; Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Lu, L.; Luo, B.; et al. Development of an asymmetric alginate hydrogel loaded with S-nitrosoglutathione and its application in chronic wound healing. Gels 2025, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, J.; Pedaparthi, S.; Hopkins, S.P.; Goudie, M.J.; Douglass, M.E.; Handa, H. Antibacterial and cellular response toward a gasotransmitter-based hybrid wound dressing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 4002–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjooee, K.; Oustadi, F.; Golaghaei, A.; Nassireslami, E. Carboxymethyl chitosan–alginate hydrogel containing GSNO with the ability to nitric oxide release for diabetic wound healing. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 17, 055013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kwak, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Hlaing, S.P.; Hasan, N.; Cao, J.; Yoo, J.-W. Nitric oxide-releasing S-nitrosoglutathione-conjugated poly (Lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for the treatment of MRSA-infected cutaneous wounds. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catori, D.M.; da Silva, L.C.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Nguyen, G.H.; Moses, J.C.; Brisbois, E.J.; Handa, H.; de Oliveira, M.G. In situ photo-crosslinkable hyaluronic acid/gelatin hydrogel for local nitric oxide delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 48930–48944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sheng, H.; Cao, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Yan, F.; Ding, D.; Cheng, N. S-nitrosoglutathione functionalized polydopamine nanoparticles incorporated into chitosan/gelatin hydrogel films with NIR-controlled photothermal/NO-releasing therapy for enhanced wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Lin, X.; Yu, M.; Mondal, A.K.; Wu, H. Recent advances in TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers: Oxidation mechanism, characterization, properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Low, Z.X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, H. TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers: A renewable nanomaterial for environmental and energy applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamo, A.K. Nanocellulose-based hydrogels as versatile materials with interesting functional properties for tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 7692–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, C.; Han, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, K.; Duan, G. Preparation of nanocellulose and its applications in wound dressing: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregori, B.; Guidoni, L.; Chiavarino, B.; Scuderi, D.; Nicol, E.; Frison, G.; Fornarini, S.; Crestoni, M.E. Vibrational signatures of S-nitrosoglutathione as gaseous, protonated species. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 12371–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.; Genoni, A.; Boudier, A.; Leroy, P.; Ruiz-Lopez, M.F. Structure and stability studies of pharmacologically relevant S-nitrosothiols: A theoretical approach. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 4191–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, J.; Tu, X.; Tan, D.; Yu, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Zhou, C. Rapid formulation alginate dressing with sustained nitric oxide release: A dual-action approach for antimicrobial and angiogenic benefits. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 176, 214350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, H.V.; da Silva, L.C.E.; de Almeida Piscelli, B.; dos Santos, B.R.G.; Guizoni, D.M.; Davel, A.P.; Cormanich, R.A.; de Oliveira, M.G. Nitric oxide-releasing PHEMA/polysilsesquioxane photocrosslinked hybrids. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 45048–45060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.W. Some observations concerning the S-nitroso and S-phenylsulphonyl derivatives of L-cysteine and glutathione. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2013–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarek, Z.; Gergely, J. Zero-length crosslinking procedure with the use of active esters. Anal. Biochem. 1990, 185, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamand, R.; Dalsgaard, T.; Jensen, F.B.; Simonsen, U.; Roepstorff, A.; Fago, A. Generation of nitric oxide from nitrite by carbonic anhydrase: A possible link between metabolic activity and vasodilation. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 297, H2068–H2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, J.M.; Liras, M.; Quijada-Garrido, I.; Gallardo, A.; Paris, R. Swelling control in thermo-responsive hydrogels based on 2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl methacrylate by crosslinking and copolymerization with N-isopropylacrylamide. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourd’heuil, D.; Jourd’heuil, F.L.; Feelisch, M. Oxidation and nitrosation of thiols at low micromolar exposure to nitric oxide: Evidence for a free radical mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 15720–15726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrino, M.T.; Weller, R.B.; Paganotti, A.; Seabra, A.B. Delivering nitric oxide into human skin from encapsulated S-nitrosoglutathione under UV light: An in vitro and ex vivo study. Nitric Oxide 2020, 94, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominaga, H.; Ishiyama, M.; Ohseto, F.; Sasamoto, K.; Hamamoto, T.; Suzuki, K.; Watanabe, M. A water-soluble tetrazolium salt useful for colorimetric cell viability assay. Anal. Commun. 1999, 36, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasri, W.; Thu, V.T.; Corpuz, A.; Nguyen, L.T. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from corncob via ionic liquid [Bmim][HSO4] hydrolysis: Effects of major process conditions on dimensions of the product. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 19020–19029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Lee, J.; Kwak, D.; Kim, H.; Saparbayeva, A.; Ahn, H.-J.; Yoon, I.-S.; Kim, M.-S.; Jung, Y.; Yoo, J.-W. Diethylenetriamine/NONOate-doped alginate hydrogel with sustained nitric oxide release and minimal toxicity to accelerate healing of MRSA-infected wounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovski, K.; Chau, T.; Robinson, C.J.; MacDonald, S.D.; Peterson, A.M.; Mashek, C.M.; Wallin, W.A.; Rimkus, M.; Montgomery, F.; Lucas da Silva, J.; et al. Antibacterial activity of high-dose nitric oxide against pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus disease. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, e000154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, F.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T.; Feng, T.; Song, J.; Li, P.; Huang, W. Nitric oxide-releasing polymeric materials for antimicrobial applications: A review. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, G.; Aveyard, J.; Fothergill, J.L.; McBride, F.; Raval, R.; D’Sa, R.A. Nitric oxide releasing polymeric coatings for the prevention of biofilm formation. Polymers 2017, 9, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, M.B.; Barbul, A. Role of nitric oxide in wound repair. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 183, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, T.-H.; Jang, H.-J.; Jeong, G.-J.; Yoon, J.-K. Hydrogel-based nitric oxide delivery systems for enhanced wound healing. Gels 2025, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Ye, S.; Li, X. Hydrogel-based dressings designed to facilitate wound healing. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 1364–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, J. Advances in functional hydrogel wound dressings: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasra, S.; Patel, M.; Shukla, H.; Bhatt, M.; Kumar, A. Functional hydrogel-based wound dressings: A review on biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. Life Sci. 2023, 334, 122232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwak, D.; Dagar, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Ullah, M.; Hakim, M.L.; Kim, M.; Yeasmin, M.S.; Nyalali, N.; et al. Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosoglutathione-Conjugated TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose Hydrogel for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121623

Kwak D, Dagar C, Kim J, Lee J, Kim H, Ullah M, Hakim ML, Kim M, Yeasmin MS, Nyalali N, et al. Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosoglutathione-Conjugated TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose Hydrogel for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121623

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwak, Dongmin, Chavi Dagar, Jihyun Kim, Juho Lee, Hyunwoo Kim, Muneeb Ullah, Md. Lukman Hakim, Minjeong Kim, Mst. Sanzida Yeasmin, Ng’wisho Nyalali, and et al. 2025. "Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosoglutathione-Conjugated TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose Hydrogel for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121623

APA StyleKwak, D., Dagar, C., Kim, J., Lee, J., Kim, H., Ullah, M., Hakim, M. L., Kim, M., Yeasmin, M. S., Nyalali, N., & Yoo, J.-W. (2025). Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosoglutathione-Conjugated TEMPO-Oxidized Nanocellulose Hydrogel for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121623