1. Introduction

Inhalation products are widely used to treat and prevent lung infections such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Among the different types of existing delivery systems for pulmonary administration, dry powder inhalers (DPIs) are extensively used owing to their accuracy, stability, and facility of use. In particular, capsule-based DPIs (cDPIs) present the advantage of dose flexibility and low development manufacturing costs with a wide offer of off-the-shelf devices.

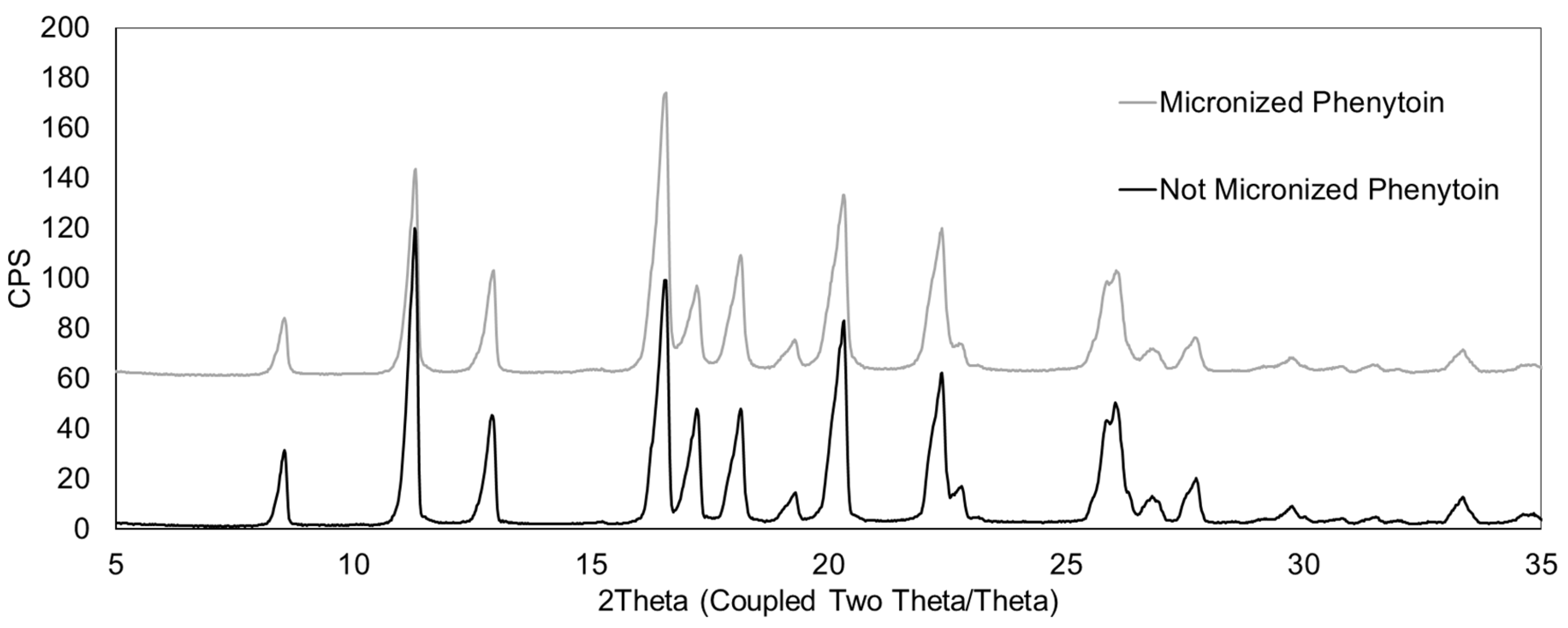

The performance of cDPIs is influenced by many factors. Among these, the importance of formulation is well documented, with numerous studies addressing the impact of the type of formulation (carrier-based or carrier-free formulation) excipient selection or importance of API micronization [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The impact of devices on the efficacy of cDPIs is also reported in several scientific articles [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, although the interdependence between formulation, device, and capsule on pulmonary drug delivery is often mentioned, the impact of the capsule itself is relatively under-investigated. Yet formulators can choose from a variety of capsule types, and this choice can substantially influence cPDI performance.

Hard gelatin capsules (HGCs), traditionally produced by dipping cold metal pins into hot gelatin solutions, remain widely used in cDPIs. However, their relatively high water content (13–16%) makes them prone to brittleness and cracking under the low relative humidity conditions typical of DPI environments. To overcome this potential limitation, plasticizers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been added to gelatin to improve mechanical flexibility of the capsules. Later, hypromellose (HPMC) capsules, containing reduced water content (3–9%) have emerged as promising alternatives. These HPMC capsules can be manufactured by the traditional cold-gelation method, including a gelling agent in the polymer formulation preparation, as for Zephyr® Vcaps® capsule (VC) and Quali-V® I, or fabricated using a thermo-gelation process without gelling agent. This method consists in dipping hot metal pins in a cold HPMC solution and is used to manufacture Zephyr® Vcaps® Plus (VCP) and Vcaps® Plus Zephyr Inhance™ capsule (VCP-I). The latter capsule is obtained with an improved manufacturing process enabling reduced capsule variability.

Low water content is particularly advantageous for DPIs because it helps preserve formulation stability and ensures consistent powder release [

9]. Environmental conditions, particularly temperature and relative humidity (RH), significantly influence the moisture content and mechanical behavior of capsule polymers, which in turn affects their physicochemical properties and critical aerosol performance metrics. The polymer chemistry and water sorption characteristics of HPMC and gelatin capsules create distinct responses to environmental stress, with implications for aerodynamic particle size distribution (APSD), fine particle fraction (FPF), and emitted dose consistency [

10]. While the different HPMC capsule variants are recognized for their beneficial characteristics in terms of low water content and improved control over capsule mechanical properties (avoiding brittleness) [

11], their impact on DPI aerosolization performance and drug lung delivery remains insufficiently understood.

Recent investigations highlight that capsule material (e.g., gelatin versus HPMC) significantly influences key performance attributes: for instance, HPMC capsules typically exhibit lower moisture content and greater mechanical robustness under low-humidity conditions, translating into improved capsule puncture behavior, reduced powder retention and enhanced fine-particle dose when compared to gelatin shells [

12]. Moreover, capsule tribo-electrification behavior, aperture geometry (size, number, orientation of puncture pins), and capsule-chamber motion dynamics have been shown to interplay with powder properties and device flow regimes—leading to differences in aerosolization efficiency and dose reproducibility [

13]. Hence, the capsule is not merely a passive container but a critical component influencing metering, release, dispersion, and ultimately lung deposition—a fact that warrants systematically including capsule properties in the quality-by-design framework of cDPI development [

6].

This study investigates the underexplored influence of capsule type on the aerodynamic performance of a model carrier-based DPI formulation used with a well-established inhalation device. A complete capsule portfolio was evaluated in parallel using complementary techniques to assess both performance and mechanical properties and to correlate capsule-specific characteristics with drug delivery behavior. The novelty of this work lies in the first systematic evaluation of the newly developed VCP-I capsule, manufactured using an improved thermo-gelation process, and in assessing its performance relative to VCP and cold-gelled capsules. This integrated approach provides new insight into the critical role of capsules in DPI performance.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that capsule type significantly influences the aerodynamic performance of carrier-based dry powder inhaler formulations, with HPMC-based VCP-I capsules exhibiting superior drug delivery efficiency compared to gelatin-based capsules. VCP-I capsules achieved the lowest API retention (6.30 ± 0.23% of nominal dose) with minimal variability, resulting in 51% of the encapsulated phenytoin being available for lung absorption when used with the RS01 device.

While capsule-based DPI performance depends on numerous interconnected factors, including formulation composition (API particle size and physicochemical state, and carrier selection and particle size distribution), manufacturing processes (micronization conditions, blending parameters, and capsule filling), device characteristics (piercing mechanisms, airflow resistance, and chamber geometry), and patient variables (inhalation flow rate, and inspiratory capacity), the capsule component itself has received disproportionately limited scientific attention despite its potential impact on drug delivery efficiency. This knowledge gap provided the rationale for systematically evaluating capsule type effects on aerodynamic behavior using a well-characterized carrier-based formulation and the standardized RS01® device.

Carrier-based DPI formulations rely on precisely controlled cohesive and adhesive interactions between micronized API particles (1–5 μm), coarse lactose carrier particles (50–150 μm), and fine excipient particles that modulate inter-particulate forces. Within this framework, capsule material properties introduce additional interaction mechanisms that significantly influence overall performance through powder adhesion to interior surfaces during aerosolization. The capsule interior presents substantial contact area where particles can adhere via the same fundamental force mechanisms governing drug–carrier interactions, with material-specific differences in polymer chemistry, surface energy, moisture content, and manufacturing-induced surface characteristics affecting powder retention and release consistency.

4.1. Primary Performance Findings

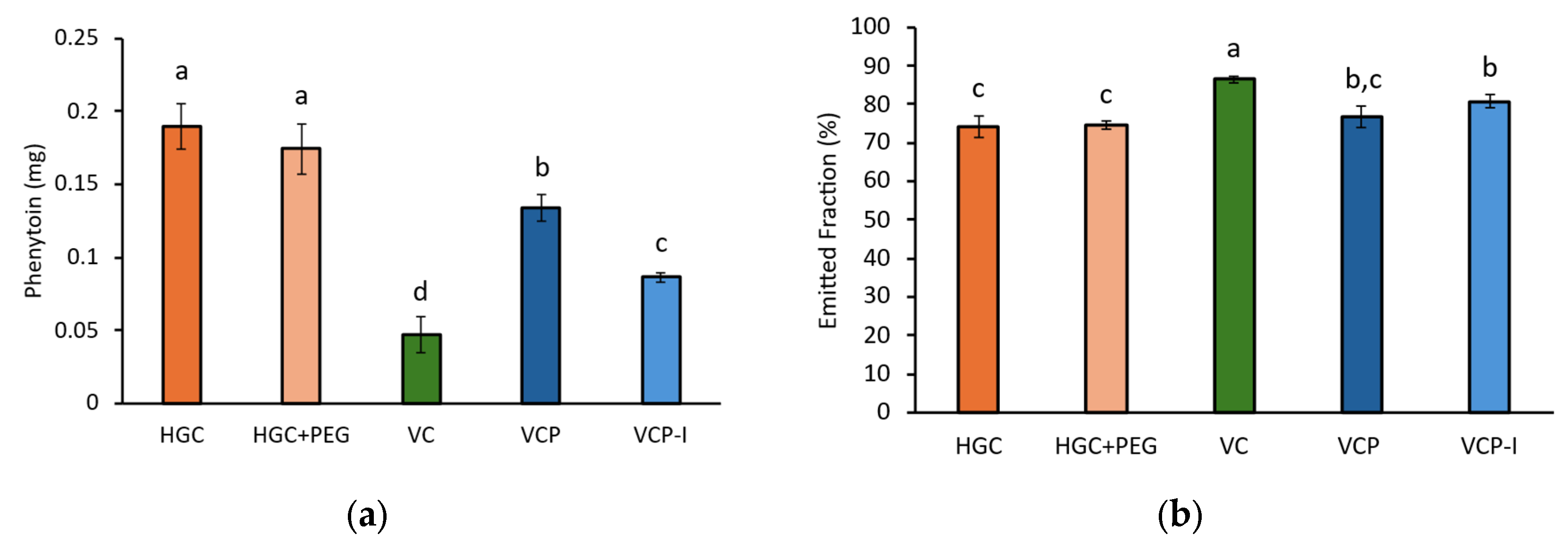

Capsule type influence on the aerodynamic performances of the model formulation was evaluated by NGI. Results show that API retention in the capsule was influenced by the type of capsule. The performance hierarchy observed (VC ≥ VCP-I > VCP > gelatin-based capsules) for API retention represents a clinically meaningful difference in drug delivery efficiency. Importantly, this study provides the first evaluation of the newly developed VCP-I capsule, which has not previously been tested. The comparable performance of VCP-I to VC demonstrates that thermo-gelled capsules manufactured using an improved fabrication process can achieve performance equivalent to cold-gelled VC capsules. These results are consistent with those obtained in a study using a ternary blend formulation with 0.05% formoterol, stored at 50% RH, where the same capsule ranking was observed, although the impact of the capsule evaluated was on 10 capsules per test (

n = 3) [

13]. With gelatin-based capsules retaining 12–15% of the nominal dose compared to 3–6% for optimal HPMC capsules, this translates to approximately 10% more active pharmaceutical ingredient being available for pulmonary delivery. For respiratory medications where precise dosing is critical for therapeutic efficacy and safety margins, this improvement could significantly impact clinical outcomes.

Capsule retention has a direct impact on EF, corresponding to the fraction of dose released from the capsule and device, for which higher values were obtained with VC followed by VCP-I, VCP, and then both gelatin-based capsules.

Concerning the FPF, no influence of the capsules was observed. This result was expected as FPF corresponds to the fraction of phenytoin from the ED with particle size below 5 µm, and therefore only takes into account what is released from the cDPI. The similarity between FPF values obtained for all capsule types highlights the robustness of the formulation, which aerosolized similarly in the NGI apparatus with a final FPF between 51% and 57%.

On the other hand, when the FPD is related to the nominal dose, capsule type has a clear influence on the results with higher values obtained for VC and VCP-I. Because of the lower variability observed with VCP-I, it can be considered as outperforming the other capsule types, enabling 51% of the encapsulated phenytoin to be available for lung absorption. VCP-I would then be recommended for the development of a cDPI product of this model phenytoin carrier-based formulation using a RS01® device.

Capsule overall appearance after powder emptying show powder retention in all capsule types and is obviously more visible in transparent capsules. With these particular capsules, it seems that powder retention is higher in VCP-I followed by VC and then HGC which is not correlated with phenytoin quantification in capsules after NGI evaluation (VC > VCP-I > HGC). This reflects the importance of API quantification to evaluate the performance of cDPI.

4.2. Mechanistic Understanding of Capsule Performance Differences

The superior performance of HPMC capsules, particularly VCP-I, stems from fundamental differences in polymer chemistry, surface characteristics, and manufacturing processes that influence powder–capsule interactions through multiple mechanisms

Observations of capsule inner surface after emptying are in accordance with NGI results with more powder retained on the surface of gelatin-based capsules compared to HPMC-based capsules.

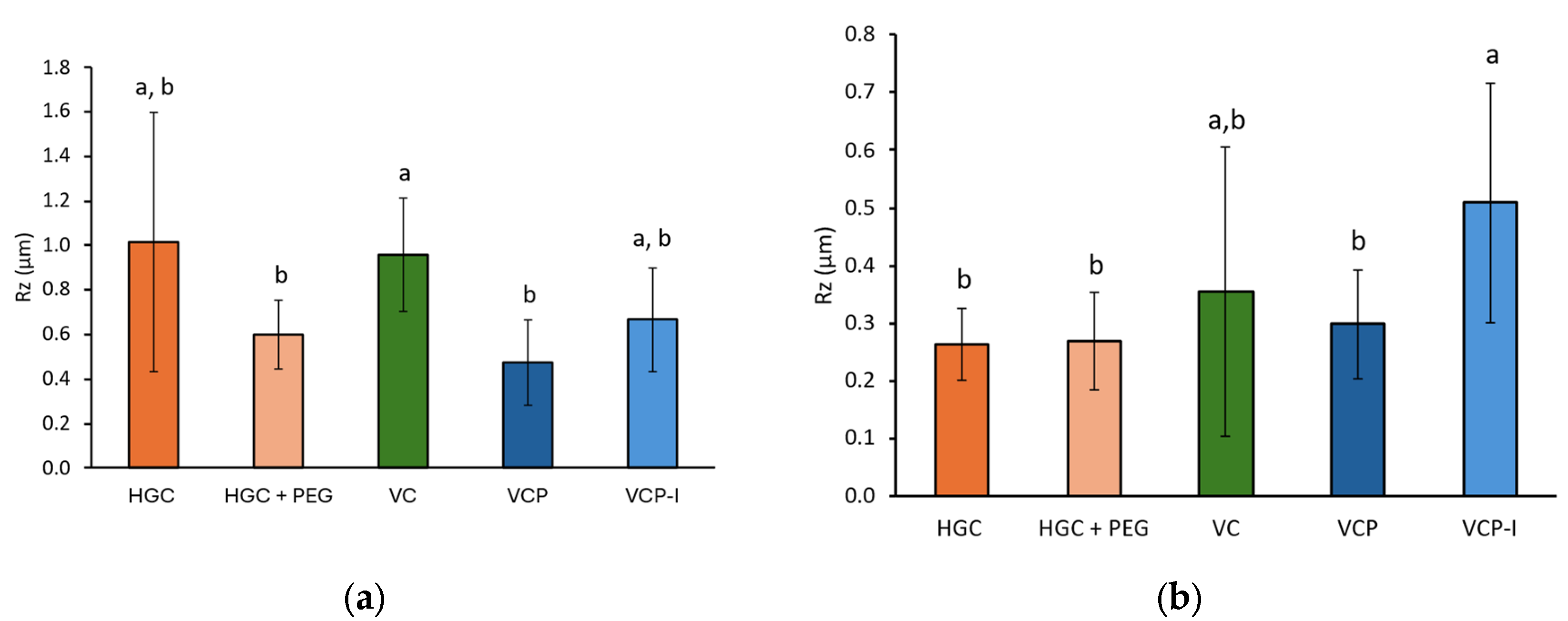

SEM revealed distinct morphological differences between capsule types. Gelatin-based capsules exhibited heterogeneous surfaces with droplet-like structures. In contrast, HPMC capsules presented smoother surfaces with a more uniform appearance. However, these observations could not be correlated with rugosity measurements, which show high variability and do not clearly discriminate the different capsule polymers and fabrication processes. No parallel could be established with NGI results.

A study performed by Saleem et al. used atomic force microscopy to map the inner surface of HPMC capsules with various lubricant content. This study reports that lubricant content can smoothen inner surface of capsules and facilitate API emission upon inhalation [

14]. In the present study with phenytoin, and contrary to conventional understanding, lubricant content did not correlate directly with capsule performance. Although different lubricants are used across the capsule types evaluated (depending on the polymer and fabrication process) this diversity prevents any direct comparison of lubricant composition or its impact on performance between all capsule types. The only meaningful comparison can therefore be made between VCP and VCP-I, which share the same polymer and fabrication process. In VCP-I, the thermo-gelation fabrication process has been optimized to reduce the amount of deposited lubricant (VCP-I = 46 ppm vs. VCP = 174 ppm). Despite having the lowest lubricant content, VCP-I demonstrated excellent performance and is even comparable to that of VC capsules fabricated with a cold-gelation process (209 ppm) generally recognized as performing better than capsules fabricated by thermo-gelation process [

13]. This suggests that lubricant composition, distribution, and integration within the polymer matrix, rather than absolute content, may be more critical for performance. The improved manufacturing process used for VCP-I capsules results in more uniform lubricant distribution, explaining the superior capsule performance despite lower total lubricant content.

Environmental humidity conditions critically influence both capsule physicochemical properties and aerodynamic performance metrics. Studies have demonstrated that exposure to elevated humidity (75% RH at 40 °C) can result in up to 50% reduction in FPD for certain DPI products, with corresponding decreases in FPF due to moisture-induced particle agglomeration and altered inter-particulate forces [

15]. On a capsule perspective, recent findings by Magramane et al. (2025) confirmed that under elevated humidity (25 °C, 75% RH), HPMC capsules maintain their mechanical integrity and puncture resistance, while gelatin capsules soften, plasticize, and suffer a marked decline in structural stability [

12]. Their microstructural analysis (via positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy) revealed that HPMC capsules undergo dynamic free-volume expansion, in contrast to the more rigid semi-crystalline structure of gelatin [

12]. In addition, a seminal study by Benke et al. (2021) directly compared gelatin, gelatin-PEG, and HPMC capsules in the context of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride DPI formulations [

16]. They carried out a long-term stability study (6 months, ICH conditions) and found that HPMC capsules provided the greatest formulation stability and the best in vitro aerodynamic performance, relative to both gelatin and gelatin-PEG shells. Specifically, they observed that the residual solvent content of the HPMC capsules decreased the least over time, helping preserve capsule integrity, reduce fragmentation, and ultimately improve lung deposition—with a ~10% higher deposition in the in vitro lung model compared to the other capsule types [

16]. Nevertheless, it is common for DPI applications to work under much lower RH because of API and formulation sensitivity to water (i.e., spray-dried formulations). In this case, capsule flexibility may impact the emitted dose due to an increased risk of capsule brittleness. In particular, storage below 40% RH increases gelatin capsule brittleness, potentially compromising puncture performance and dose reproducibility. This capsule moisture sensitivity directly impacts critical quality attributes including aerodynamic particle size distribution; hygroscopic excipients exposed to elevated humidity form stronger agglomerates through increased capillary forces, resulting in reduced fine particle fraction and altered lung deposition profiles.

Capsules based on gelatin and HPMC do not possess the same moisture content with, respectively, 13 to 16% and 3 to 9% [

11]. In the present study, all capsules were all carefully equilibrated at 45% RH consistent with the water activity of the formulation. Therefore, potential water transfer from the capsule to the formulation cannot justify the differences in capsule retention observed between the different capsule types. Moreover, because at 45% RH all capsule types were in their recommended conditions of use (from 35 to 65% RH between 15 and 25 °C), none of them exhibited brittleness upon puncturing and all presented regular puncturing holes with flaps remaining well attached to the capsule parts. Capsule brittleness was therefore not responsible for the differences observed in NGI. The selected RH condition falls in the classical range of previously published conditions in cDPI studies.

In particular, Stankovic-Brandl et al. report an increase in FPF of budesonide at 51% RH compared to 22% RH, using cold-gelled HPMC capsule with a carrier-based formulation [

17]. The superior performance of HPMC capsules with carrier-based formulations observed with the phenytoin carrier-based formulation aligns with previous publications. Wauthoz et al. similarly demonstrated superior performance of HPMC capsules, particularly those manufactured by a cold-gelation process, compared with gelatin capsules using formoterol formulations, with no significant differences between Quali-V

®-I (Qualicaps) and VC capsules at 50% RH [

13]. Likewise, Ding et al. found no statistical differences in emitted fraction or FPF among four cold-gelled HPMC capsule types filled with a budesonide carrier-blend formulation tested at 40% RH [

18]. Although the impact of electrostatic charges on powder deagglomeration and consequently on DPI performance is already well documented, limited information is available regarding the impact of capsule charging on powder retention upon cDPI device actuation by inhalation (and capsule spinning inside the chamber). In this study, the quantity of electric charges of capsules equilibrated at 45% RH was measured during a flow in contact with ABS, which is the major constituent of the RS01

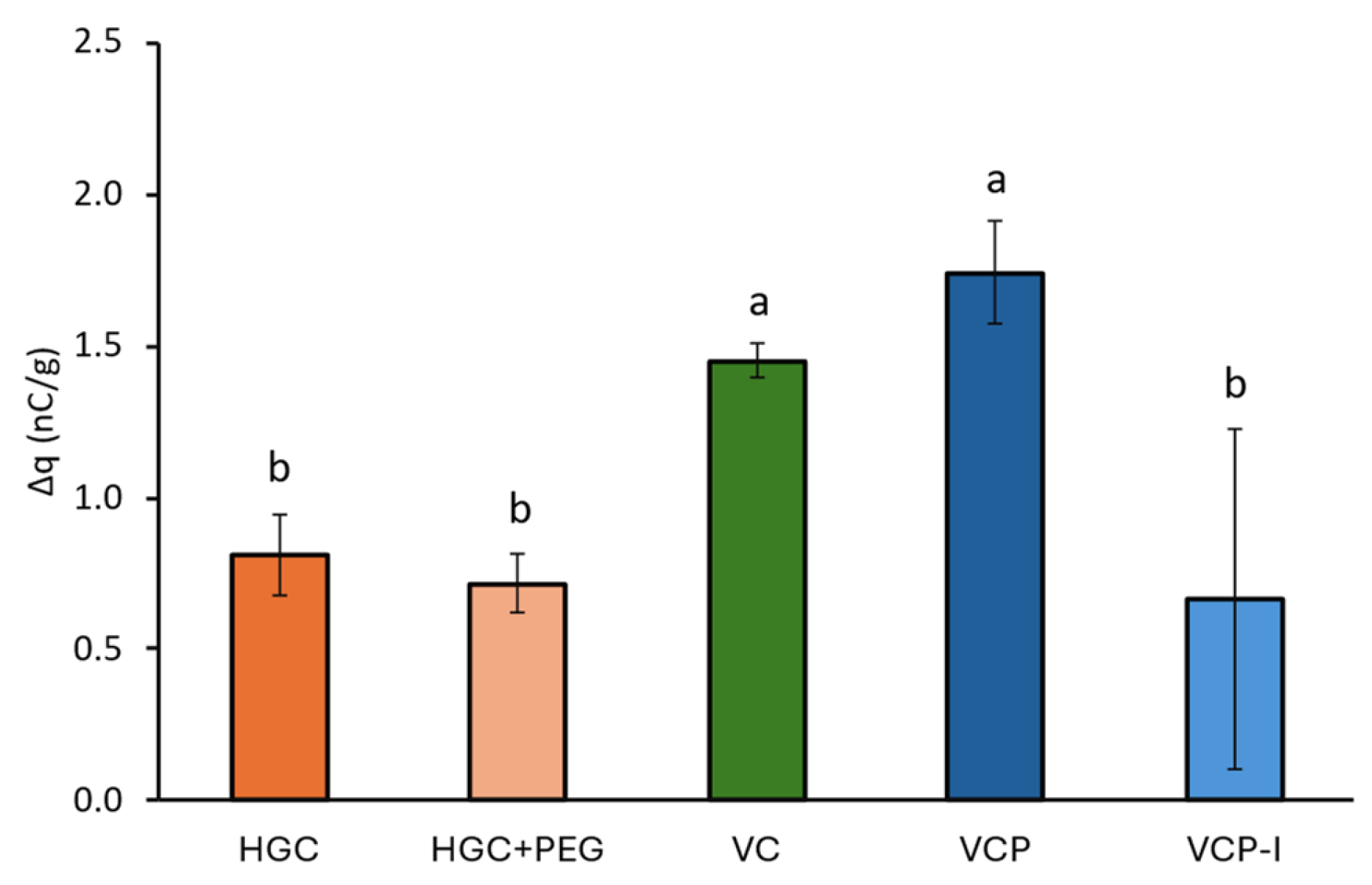

® device. The measured density of charges were all positives, below 2 nC/g for all capsule types, which is consistent with previously reported results by Pinto et al., although stainless steel and PVC were used in their set-up which does not allow direct result comparison [

10]. Furthermore, no clear trends could be drawn from the results with lowest values obtained for both gelatin-based capsules but also VCP-I, with very high variability for the latter. Although VCP and VCP-I are constituted of the same polymer and obtained by the same thermo-gelation manufacturing process, they exhibited a different density of charges on ABS and different variability. Plus, the obtained results could not be correlated with phenytoin retention in these capsules after NGI which may indicate that capsule charging in these conditions had limited impact on cDPI performances.

4.3. Quality by Design Implications

The batch-to-batch consistency demonstrated by VCP-I capsules (three batches showing no statistically significant differences in key performance parameters) supports their suitability for commercial development under Quality by Design principles. This reproducibility, combined with superior performance, positions VCP-I as the preferred choice for this formulation-device combination. The lower variability also suggests reduced risk of batch failures during commercial manufacturing.

4.4. Study Limitations

This study employed a single ternary lactose–phenytoin formulation. Different APIs with varying physicochemical properties (particle size, surface energy, and hygroscopicity) may interact differently with capsule surfaces, potentially altering the performance hierarchy observed. Similarly, results are specific to the RS01 low-resistance device. Different piercing mechanisms, chamber geometries, and airflow patterns in other devices may yield different relative capsule performance rankings.

While 45% RH represents typical storage conditions, real-world usage encompasses a broader range of humidity and temperature conditions that may affect relative capsule performance, particularly given the different moisture sensitivities of gelatin and HPMC materials. The present study was conducted under controlled laboratory which, while representative of standard pharmaceutical manufacturing and testing environments, may not fully capture the complexity of real-world environmental exposures. Clinical use scenarios can involve significantly more challenging conditions, including tropical climates with sustained high humidity (>70% RH), arid environments with very low humidity (<20% RH), and substantial diurnal temperature fluctuations (>15 °C). Such extreme or variable conditions can differentially affect gelatin and HPMC capsule performance through altered moisture content, mechanical properties, and electrostatic behavior.

The current study primarily relied on morphological observations and basic surface measurements. Advanced characterization techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Dynamic Vapor Sorption analysis, atomic force microscopy, and inverse gas chromatography could provide deeper insights into surface chemistry and energetics relevant to powder–capsule interactions.

4.5. Recommendations for Formulation Development

Although the characterization tests performed in this study do not enable a clear understanding of the parameters impacting cDPI capsule performances, the NGI results show that the capsule can have a role on DPI drug product performance. With RS01 device, the designed phenytoin formulation should be filled in a VCP-I capsule to maximize the dose delivered to the lungs. In addition, repeated NGI tests with three different batches of VCP-I confirm the robustness of this capsule, with no statistical differences observed among API retention, EF, FPF, and FPD/nominal.

Based on these findings, formulators developing carrier-based DPI products should consider the following:

Capsule Selection Criteria: Prioritize HPMC capsules manufactured via optimized thermo-gelation processes for consistent performance, particularly for moisture-sensitive formulations or products requiring tight dose uniformity specifications.

Development Strategy: Include capsule type as a critical material attribute in early formulation screening, as the 10% improvement in deliverable dose observed here could obviate the need for dose increases or formulation modifications.

Quality Control: Implement batch-to-batch capsule performance testing as part of incoming material specifications, focusing on reproducibility metrics rather than absolute performance values.

Stability Testing Protocol: Design stability protocols that evaluate performance under relevant environmental stress conditions, including temperature–humidity cycling to simulate real-world patient use scenarios. Critical aerodynamic performance attributes (APSD, FPF, FPD, and emitted dose) should be monitored alongside traditional chemical stability endpoints to ensure maintained therapeutic performance under accelerated and long-term storage conditions, with particular focus on moisture-induced changes in inter-particulate forces and powder flowability.