PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Nanoformulations: Overview, Strategies, and Recent Advances

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nanocarrier Systems for Drug Delivery

1.2. Rationale for Using PLGA

1.3. Importance of Co-Delivery Strategies

1.4. Research Landscape and Methodology of This Review

2. PLGA: Chemical Structure and Physicochemical Properties

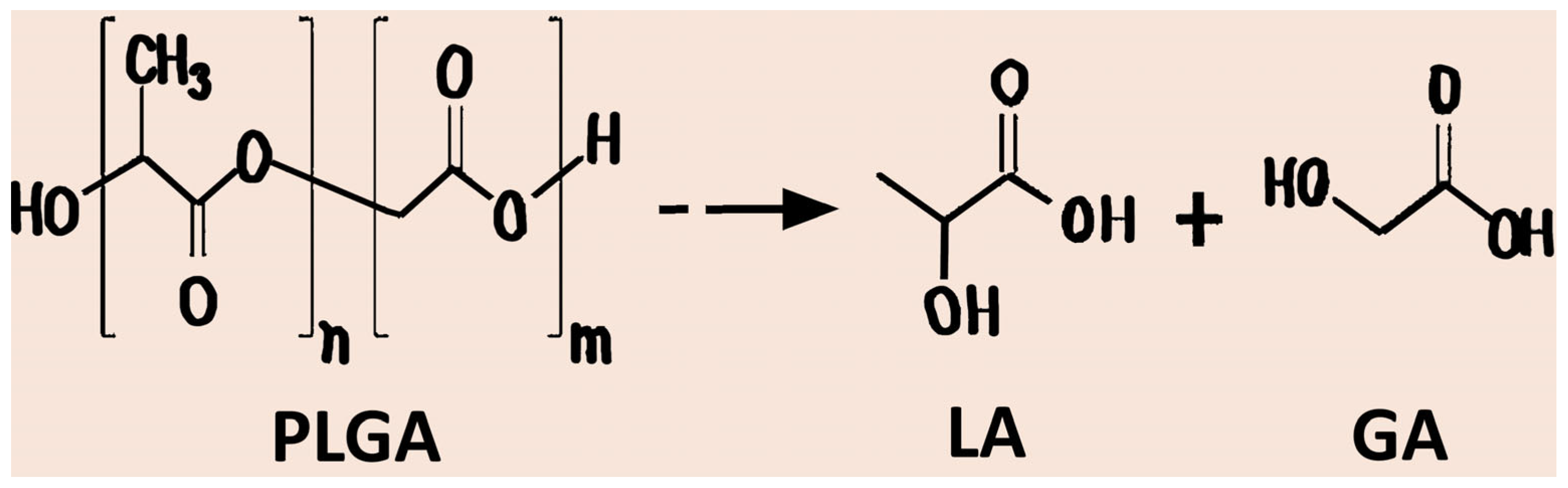

2.1. Chemical Structure and Physicochemical Parameters

2.2. Applied Properties and Limitations

3. Fabrication Strategies for PLGA-Based Nanoformulations

3.1. Conventional Techniques for PLGA Nanoparticle Fabrication

3.2. Advanced Techniques for PLGA Nanoparticle Fabrication

3.3. Optimisation Parameters for PLGA Nanocarriers

3.4. Structural Designs: Single-Carrier Encapsulation, Core–Shell, Layered, or Hybrid Lipid–Polymer Architectures

3.5. Approaches to Scale-Up and Reproducibility of PLGA Nanocarriers

4. PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Systems

4.1. Classification of Co-Delivery Types

4.2. Drug–Drug Co-Delivery

4.3. Drug–Gene Co-Delivery

4.4. Gene–Gene Co-Delivery

4.5. Multi-Modal Co-Delivery

4.6. Case Studies of Co-Delivery Platforms

5. Mechanisms Governing Drug Release

5.1. Influence of Polymer Properties on PLGA Degradation

5.2. The Physical and Chemical Mechanisms Governing Drug Release

5.3. Relevant Mathematical Modelling Approaches

5.4. Programmed Release Strategies for Co-Delivery Systems

6. Surface Modification and Functionalization

7. Clinical Translation and Regulatory Considerations

7.1. Clinical Translation

7.2. Regulatory Status of PLGA and Co-Loaded Nanocarriers (FDA, EMA)

| Brand Name | Active Ingredient | Indication | Method | Route of Administration | Year of Approval | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decapeptyl® | Triptorelin pamoate | Inhibition of gonadotropin secretion (Prostate cancer) | NA | Intramuscular injection | 1986 (EU) | [77,146] |

| Lupron Depot® | Leuprolide acetate | Advanced prostate cancer, endometriosis, fibroid | Water-in-oil emulsification | Intramuscular, monthly | 1989 (FDA), 1995, 1997, 2011 | [147] |

| Zoladex® | Goserelin acetate | Advanced breast cancer in pre-and perimenopausal women, endometriosis, prostate cancer | Hot melt extrusion | Subcutaneous implant | ~1989 | [148] |

| Sandostatin® LAR Depot | Octreotide acetate | Acromegaly | Emulsion solvent evaporation | Intramuscular microspheres | 1998 | [149] |

| Nutropin Depot® | Somatropin | Growth hormone deficiency | Spray drying | Subcutaneous injection | 1999 | [150] |

| Eligard® | Leuprolide acetate (in situ PLGA implant) | Advanced prostate cancer | PLGA dissolved in a biocompatible solvent such as N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone | Subcutaneous injection | 2002 | [146,151] |

| Risperdal® Consta™ | Risperidone | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder | Emulsion solvent evaporation | Intramuscular, every 2 weeks | 2003 | [149] |

| Vivitrol® | Naltrexone | Alcohol dependence, opioid dependence | Emulsion solvent evaporation | Long-acting intramuscular injection | 2006 | [146] |

| Somatuline® LA | Lanreotide acetate | Acromegaly, carcinoid syndrome | Spray drying | Intramuscular PLGA microparticles | 2007 | [147] |

| Triptodur™ | Triptorelin pamoate | Central precocious puberty | Oil-in-water emulsification/ | Intramuscular injection | 2017 | [77] |

| Perseris™ | Risperidone | Adult schizophrenia | NA | Subcutaneous injection | 2018 | [151] |

| Fensolvi® | Leuprolide acetate | Central precocious puberty | NA | Subcutaneous injection | 2020 | [146] |

8. Challenges and Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adepu, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Controlled Drug Delivery Systems: Current Status and Future Directions. Molecules 2021, 26, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; He, M.; Lin, C.; Ma, W.; Ai, Y.; Wang, J.; Liang, Q. Multifunctional Nanocarrier Drug Delivery Systems: From Diverse Design to Precise Biomedical Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, e02178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.J.; Abdelfattah, N.S.; Hostetler, A.; Irvine, D.J. Progress in Cancer Vaccines Enabled by Nanotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanović, M.; Filipović, N. A Review of Recent Developments in Biopolymer Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems with Antioxidative Properties: Insights into the Last Five Years. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.M.; Škapin, S.D.; Bračko, I.; Milenković, M.; Petković, J.; Filipič, M.; Uskoković, D.P. Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity, Cytotoxicity Assessment and ROS-Inducing Potential. Polymer 2012, 53, 2818–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, P.; Pavlović, V.; Nunić, J.; Cundrič, S.; Filipič, M.; Stevanović, M. Development of Lyophilized Spherical Particles of Poly(Epsilon- Caprolactone) and Examination of Their Morphology, Cytocompatibility and Influence on the Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonara, L.; Triantafyllopoulou, E.; Chountoulesi, M.; Pippa, N.; Dallas, P.P.; Rekkas, D.M. Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Concepts and Recent Advances in Transdermal Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sohel Rana, M.; Huang, L.; Qian, K. An Antibacterial Sensitive Wearable Biosensor Enabled by Engineered Metal-Boride-Based Organic Electrochemical Transistors and Hydrogel Microneedles. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 18590–18599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qian, K.; Huang, L. Emerging Biosensors Based on Noble Metal Self-Assembly for In Vitro Disease Diagnosis. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2023, 3, 2200148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, R.; Yan, X.; Shi, L.; et al. Defective Fe Metal–Organic Frameworks Enhance Metabolic Profiling for High-Accuracy Diagnosis of Human Cancers. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanović, M.; Filipović, N.; Djurdjević, J.; Lukić, M.; Milenković, M.; Boccaccini, A. 45S5Bioglass®-Based Scaffolds Coated with Selenium Nanoparticles or with Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Selenium Particles: Processing, Evaluation and Antibacterial Activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 132, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanović, M. Biomedical Applications of Nanostructured Polymeric Materials. In Nanostructured Polymer Composites for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Song, N.; Qian, D.; Gu, S.; Pu, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Qian, K. Porous Inorganic Materials for Bioanalysis and Diagnostic Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 4092–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnikrishnan, G.; Joy, A.; Megha, M.; Kolanthai, E.; Senthilkumar, M. Exploration of Inorganic Nanoparticles for Revolutionary Drug Delivery Applications: A Critical Review. Discov. Nano 2023, 18, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, S.; Jacobsen, A.-C.; Teleki, A. Inorganic Nanoparticles for Oral Drug Delivery: Opportunities, Barriers, and Future Perspectives. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 38, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Kim, J.; Kwok, C.; Le Devedec, F.; Allen, C. A Dataset on Formulation Parameters and Characteristics of Drug-Loaded PLGA Microparticles. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Maksin, T.; Petković, J.; Filipič, M.; Uskoković, D. An Innovative, Quick and Convenient Labeling Method for the Investigation of Pharmacological Behavior and the Metabolism of Poly(DL-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanospheres. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 335102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Verma, M.; Lakhanpal, S.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, M.R.; Bhat, M.; Sharma, S.; Alam, M.W.; Khan, F. An Updated Review Summarizing the Anticancer Potential of Poly(Lactic- Co -Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) Based Curcumin, Epigallocatechin Gallate, and Resveratrol Nanocarriers. Biopolymers 2025, 116, e23637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Pavlović, V.; Petković, J.; Filipič, M.; Uskoković, D. ROS-Inducing Potential, Influence of Different Porogens and in Vitro Degradation of Poly (D,L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide)-Based Material. Express Polym. Lett. 2011, 5, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukomanović, M.; Škapin, S.D.; Jančar, B.; Maksin, T.; Ignjatović, N.; Uskoković, V.; Uskoković, D. Poly(d,l-Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Hydroxyapatite Core-Shell Nanospheres. Part 1: A Multifunctional System for Controlled Drug Delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukomanović, M.; Škapin, S.D.; Poljanšek, I.; Žagar, E.; Kralj, B.; Ignjatović, N.; Uskoković, D. Poly(D,L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Hydroxyapatite Core–Shell Nanosphere. Part 2: Simultaneous Release of a Drug and a Prodrug (Clindamycin and Clindamycin Phosphate). Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukomanović, M.; Zavašnik-Bergant, T.; Bračko, I.; Škapin, S.D.; Ignjatović, N.; Radmilović, V.; Uskoković, D. Poly(d,l-Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/Hydroxyapatite Core–Shell Nanospheres. Part 3: Properties of Hydroxyapatite Nano-Rods and Investigation of a Distribution of the Drug within the Composite. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Tian, J. Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems for Synergistic Delivery of Tumor Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1111991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, X.; Yin, M.; Shen, J.; Yan, S. Recent Advances in Nanoparticle-Mediated Co-Delivery System: A Promising Strategy in Medical and Agricultural Field. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, X.; Zoulikha, M.; Boafo, G.F.; Magar, K.T.; Ju, Y.; He, W. Multifunctional Nanoparticle-Mediated Combining Therapy for Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pho-iam, T.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Somboonyosdech, C.; Sripinitchai, S.; Masaratana, P.; Sirivatanauksorn, V.; Sirivatanauksorn, Y.; Wongwan, C.; Nguyen, K.T.; Srisawat, C. PLGA Nanoparticles Containing α-Fetoprotein SiRNA Induce Apoptosis and Enhance the Cytotoxic Effects of Doxorubicin in Human Liver Cancer Cell Line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 553, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Weng, Y.; Bian, X.; Chen, X. Degradation Behaviors of Polylactic Acid, Polyglycolic Acid, and Their Copolymer Films in Simulated Marine Environments. Polymers 2024, 16, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Yu, G.W.; You, J.W.; Han, M.J.; Kang, M.J.; Ho, M.J. Sustained-Release Intra-Articular Drug Delivery: PLGA Systems in Clinical Context and Evolving Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, B.; Basko, M.; Bednarek, M.; Socka, M.; Kopka, B.; Łapienis, G.; Biela, T.; Kubisa, P.; Brzeziński, M. The Influence of the Functional End Groups on the Properties of Polylactide-Based Materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 130, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, H.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, C.; Hu, P. Recent Applications of PLGA in Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2024, 16, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, T.; Xiong, Y.; Guo, W.; Liang, Y. Multifunctional PLGA Nanosystems: Enabling Integrated Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1670397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, E.; Trutschel, M.-L.; Menzel, M.; Jacobs, J.; Kunert, J.; Scheffler, J.; Binder, W.H.; Schmelzer, C.E.H.; Plontke, S.K.; Liebau, A.; et al. Enhancing Drug Release from PEG-PLGA Implants: The Role of Hydrophilic Dexamethasone Phosphate in Modulating Release Kinetics and Degradation Behavior. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 209, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaib, L. Polymeric Nanoparticles in Targeted Drug Delivery: Unveiling the Impact of Polymer Characterization and Fabrication. Polymers 2025, 17, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H.; Wilson, R.L.; Castejon, A.M. Recent Advances in Peptide-Loaded PLGA Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery and Regenerative Medicine. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachta, P.; Jakhmola, V.; Nainwal, N.; Joshi, P.; Bahuguna, R.; Chaudhary, M.; Kumar, K.; Singh, A.; Kumar, P. A Comprehensive Study on PH-Sensitive Nanoparticles for the Efficient Delivery of Drugs. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Exp. Ther. 2025, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.-T.; Guo, H.-Y.; Zhang, C.-M.; Li, S.-F. Research Progress of Sustained-Release Microsphere Technology in Drug Delivery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2025, 15, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, K.; Kamalesu, S. State-of-the-Art Surfactants as Biomedical Game Changers: Unlocking Their Potential in Drug Delivery, Diagnostics, and Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 676, 125590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Abdu, J.O.C.; de Moura, M.F.C.S.; Silva, A.C.; Zacaron, T.M.; de Paiva, M.R.B.; Fabri, R.L.; Pittella, F.; Perrone, Í.T.; Tavares, G.D. Exploring the Potential of PLGA Nanoparticles for Enhancing Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 3542–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudoukhani, M.; Yahoum, M.M.; Ezzroug, K.; Toumi, S.; Lefnaoui, S.; Moulai-Mostefa, N.; Sid, A.N.E.H.; Tahraoui, H.; Kebir, M.; Amrane, A.; et al. Formulation and Characterization of Double Emulsions W/O/W Stabilized by Two Natural Polymers with Two Manufacturing Processes (Comparative Study). ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozalak, G.; Heyat Davoudian, S.; Natsaridis, E.; Gogniat, N.; Koşar, A.; Tagit, O. Optimization of PLGA Nanoparticle Formulation via Microfluidic and Batch Nanoprecipitation Techniques. Micromachines 2025, 16, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Huang, S.; Nie, T.; Luo, L.; Chen, T.; Chen, K.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, W. Spray Drying Strategies for the Construction of Drug-Loaded Particles: Insights into Design Principles and Pharmaceutical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 682, 125917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinchhi, P.; Patel, J.K.; Patel, M.M. High-Pressure Homogenization Techniques for Nanoparticles. In Emerging Technologies for Nanoparticle Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu, K. Applications of Freezing and Freeze-Drying in Pharmaceutical Formulations. In Survival Strategies in Extreme Cold and Desiccation; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Alkholief, M.; Kalam, M.A.; Anwer, M.K.; Alshamsan, A. Effect of Solvents, Stabilizers and the Concentration of Stabilizers on the Physical Properties of Poly(d,l-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles: Encapsulation, In Vitro Release of Indomethacin and Cytotoxicity against HepG2-Cell. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H. Exploring the Effects of Process Parameters during W/O/W Emulsion Preparation and Supercritical Fluid Extraction on the Protein Encapsulation and Release Properties of PLGA Microspheres. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, A.J.P.; de Wet-Roos, D.; Sanderson, R.D.; Klumperman, B. The Role of Surfactant in Controlling Particle Size and Stability in the Miniemulsion Polymerization of Polymeric Nanocapsules. Eur. Polym. J. 2004, 40, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, E.; Bellott, M.; Caimi, A.; Conti, B.; Dorati, R.; Conti, M.; Genta, I.; Auricchio, F. Development and optimization of microfluidic assisted manufacturing process to produce PLGA nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 629, 122368. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378517322009231 (accessed on 1 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Javid-Naderi, M.J.; Mousavi Shaegh, S.A. Advanced Microfluidic Techniques for the Preparation of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: Innovations and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, S.; Ha, E.-S.; Kim, M.-S.; Hwang, S.-J. Pharmaceutical Applications of Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Emulsions for Micro-/Nanoparticle Formation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.R.; Haemmerich, D. Review on Electrospray Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Exploring Applications. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.; Tran, H.A.; Tan, R.; Kumeria, T.; Prasad, A.A.; Tan, R.P.; Lim, K.S. Advancements in 3D-Printing Strategies towards Developing Effective Implantable Drug Delivery Systems: Recent Applications and Opportunities. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 227, 115711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Giottonini, K.Y.; Rodríguez-Córdova, R.J.; Gutiérrez-Valenzuela, C.A.; Peñuñuri-Miranda, O.; Zavala-Rivera, P.; Guerrero-Germán, P.; Lucero-Acuña, A. PLGA Nanoparticle Preparations by Emulsification and Nanoprecipitation Techniques: Effects of Formulation Parameters. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4218–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo-Santaella, T.; Ortega-Oller, I.; Padial-Molina, M.; O’Valle, F.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Jódar-Reyes, A.B.; Peula-García, J.M. Formulation, Colloidal Characterization, and In Vitro Biological Effect of BMP-2 Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for Bone Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaly, H.S.A.; Seyedasli, N.; Varamini, P. Enhanced Nanoprecipitation Method for the Production of PLGA Nanoparticles for Oncology Applications. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neustrup, M.A.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Jiskoot, W.; Bouwstra, J.A.; van der Maaden, K. A Versatile, Low-Cost Modular Microfluidic System to Prepare Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles With Encapsulated Protein. Pharm. Res. 2024, 41, 2347–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udepurkar, A.P.; Mampaey, L.; Clasen, C.; Sebastián Cabeza, V.; Kuhn, S. Microfluidic Synthesis of PLGA Nanoparticles Enabled by an Ultrasonic Microreactor. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Wilson, R.L. PLGA Implants for Controlled Drug Delivery and Regenerative Medicine: Advances, Challenges, and Clinical Potential. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Parhizkar, M.; Harker, A.; Edirisinghe, M. Constrained Composite Bayesian Optimization for Rational Synthesis of Polymeric Particles. Digit. Discov. 2025, 4, 3066–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurul, F.; Turkmen, H.; Cetin, A.E.; Topkaya, S.N. Nanomedicine: How Nanomaterials Are Transforming Drug Delivery, Bio-Imaging, and Diagnosis. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klojdová, I.; Milota, T.; Smetanová, J.; Stathopoulos, C. Encapsulation: A Strategy to Deliver Therapeutics and Bioactive Compounds? Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morker, K.A.; Ravi, P.; Purohit, D. Comprehensive Review on the Stability and Degradation of Polysorbates in Biopharmaceuticals. EJPPS Eur. J. Parenter. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, H.; Hernández-Parra, H.; Bernal-Chávez, S.A.; Del Prado-Audelo, M.L.; Caballero-Florán, I.H.; Borbolla-Jiménez, F.V.; González-Torres, M.; Magaña, J.J.; Leyva-Gómez, G. Non-Ionic Surfactants for Stabilization of Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biomedical Uses. Materials 2021, 14, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M. Polymeric Micro- and Nanoparticles for Controlled and Targeted Drug Delivery. In Nanostructures for Drug Delivery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 355–378. ISBN 9780323461436. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic, M.M.; Jordovic, B.; Uskokovic, D.P. Preparation and Characterization of Poly(D,L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles Containing Ascorbic Acid. BioMed Res. Int. 2007, 2007, 084965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goracinova, K.; Geskovski, N.; Dimchevska, S.; Li, X.; Gref, R. Multifunctional Core–Shell Polymeric and Hybrid Nanoparticles as Anticancer Nanomedicines. In Design of Nanostructures for Theranostics Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 109–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, Q.; Duan, H.; Song, J.; Yang, H. Janus Nanoparticles: From Fabrication to (Bio)Applications. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6147–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.A.A.; Ramadan, E.; Kristó, K.; Regdon, G.; Sovány, T. Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles as a Smart Drug Delivery System for Peptide/Protein Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, A.; Takeda, C.; Manzoor, A.; Tanaka, D.; Kobayashi, M.; Wadayama, Y.; Nakane, D.; Majeed, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Akitsu, T. Towards Industrially Important Applications of Enhanced Organic Reactions by Microfluidic Systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurba-Bryśkiewicz, L.; Maruszak, W.; Smuga, D.A.; Dubiel, K.; Wieczorek, M. Quality by Design (QbD) and Design of Experiments (DOE) as a Strategy for Tuning Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for RNA Delivery. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, M.S.; Thangam, R.; Sheena, T.S.; Vimala, R.T.V.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Jeganathan, K.; Thirumurugan, R. Dual Drug Loaded PLGA Nanospheres for Synergistic Efficacy in Breast Cancer Therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Afzal, O.; Najib Ullah, S.N.M.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Alkhathami, A.G.; Sahoo, A.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Almalki, W.H.; Almujri, S.S.; Abdulrahman, A.; et al. Nanocarriers for Delivering Nucleic Acids and Chemotherapeutic Agents as Combinational Approach: Challenges, Clinical Progress, and Unmet Needs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 92, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shao, A. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, F.; Shen, W.; Leng, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P. Surface PEGylated Cancer Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for Codelivery of Curcumin and Doxorubicin for the Treatment of Multidrug Resistant Esophageal Carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 688070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altanam, S.Y.; Darwish, N.; Bakillah, A. Exploring the Interplay of Antioxidants, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Potential, and Clinical Implications. Diseases 2025, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.C.; Borah, A.; Le, M.N.T.; Kawano, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Kumar, D.S. Co-Delivery of Curcumin and Bioperine via PLGA Nanoparticles to Prevent Atherosclerotic Foam Cell Formation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.W.; Tan, W.S.; Ho, K.L.; Mariatulqabtiah, A.R.; Abu Kasim, N.H.; Abd. Rahman, N.; Wong, T.W.; Chee, C.F. Challenges and Complications of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)-Based Long-Acting Drug Product Development. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, C.; Videira, M. Dual Approaches in Oncology: The Promise of SiRNA and Chemotherapy Combinations in Cancer Therapies. Onco 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Hushmandi, K.; Hashemi, F.; Rahmani Moghadam, E.; Raei, M.; Kalantari, M.; Tavakol, S.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Najafi, M.; et al. Progress in Natural Compounds/SiRNA Co-Delivery Employing Nanovehicles for Cancer Therapy. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 669–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Jing, H.; Du, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, J. Optimization of Lipid Assisted Polymeric Nanoparticles for SiRNA Delivery and Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Shao, W.; Ni, P.; Liu, Q.; Kong, W.; Shen, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, A.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Y.; et al. SiRNA/CS-PLGA Nanoparticle System Targeting Knockdown Intestinal SOAT2 Reduced Intestinal Lipid Uptake and Alleviated Obesity. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, M.; Zhang, M.; Hussain, A.; Yu, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, Y. The Landscape of Nanoparticle-Based SiRNA Delivery and Therapeutic Development. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 284–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahan, M.; Saikia, T.; Dutta, K.; Baishya, R.; Bharali, A.; Baruah, S.; Bharadwaj, R.; Medhi, S.; Sahu, B.P. Multifunctional Approach with LHRH-Mediated PLGA Nanoconjugate for Site-Specific Codelivery of Curcumin and BCL2 SiRNA in Mice Lung Cancer. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, C. Dual Targeted Nanoparticles for the Codelivery of Doxorubicin and SiRNA Cocktails to Overcome Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanati, M.; Figueroa-Espada, C.G.; Han, E.L.; Mitchell, M.J.; Yavari, S.A. Bioengineered Nanomaterials for SiRNA Therapy of Chemoresistant Cancers. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 34425–34463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, A.; Molina-Estévez, F.J.; Reyes, Á.P.; Ronco, V.; Naseem, A.; Malenšek, Š.; Pečan, P.; Santini, A.; Heredia, P.; Aguilar-González, A.; et al. Advanced Delivery Systems for Gene Editing: A Comprehensive Review from the GenE-HumDi COST Action Working Group. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Jeong, S.; Han, J.H.; Yuk, H.D.; Jeong, C.W.; Ku, J.H.; Kwak, C. Highly Efficient Nucleic Acid Encapsulation Method for Targeted Gene Therapy Using Antibody Conjugation System. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Zaidi, S.S.; Fatima, F.; Ali Zaidi, S.A.; Zhou, D.; Deng, W.; Liu, S. Engineering SiRNA Therapeutics: Challenges and Strategies. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, A.K.; Mostafavi, E. Biomaterials-Mediated CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery: Recent Challenges and Opportunities in Gene Therapy. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1259435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupbayeva, B.; Tsoy, A.; Safarova, Y.; Nurmagambetova, A.; Murata, H.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Askarova, S. Unlocking Genome Editing: Advances and Obstacles in CRISPR/Cas Delivery Technologies. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Fan, D.; Geng, X.; Zhi, G.; Wu, D.; Shen, H.; Yang, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Multifunctional Microcapsules: A Theranostic Agent for US/MR/PAT Multi-Modality Imaging and Synergistic Chemo-Photothermal Osteosarcoma Therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramírez, D.R.; Domínguez-Ríos, R.; Juárez, J.; Valdés, M.; Hassan, N.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; del Toro-Arreola, A.; Barbosa, S.; Taboada, P.; Topete, A.; et al. Biodegradable Photoresponsive Nanoparticles for Chemo-, Photothermal- and Photodynamic Therapy of Ovarian Cancer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 116, 111196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, A.K.; Chaulagain, B.; Gothwal, A.; Singh, J. Engineered PLGA Nanoparticles for Brain-Targeted Codelivery of Cannabidiol and PApoE2 through the Intranasal Route for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 3533–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.J.; van Dijk, T.; Vepris, O.; Li, T.M.W.Y.; Schomann, T.; Baldazzi, F.; Kurita, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Grosveld, F.; Philipsen, S.; et al. PLGA-Nanoparticles for Intracellular Delivery of the CRISPR-Complex to Elevate Fetal Globin Expression in Erythroid Cells. Biomaterials 2021, 268, 120580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Chauhan, V.M.; Selo, A.A.; Al-Natour, M.; Aylott, J.W.; Sarmento, B. Modelling Protein Therapeutic Co-Formulation and Co-Delivery with PLGA Nanoparticles Continuously Manufactured by Microfluidics. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, M.; Taghavi, S.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Ramezani, M.; Hashemi, M. Co-Delivery of Doxorubicin Encapsulated PLGA Nanoparticles and Bcl-XL ShRNA Using Alkyl-Modified PEI into Breast Cancer Cells. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 183, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P.; Kumar, V.; Goh, K.W.; Gupta, G.; Alsayari, A.; Wahab, S.; Sahebkar, A. PEGylated PLGA Nanoparticles: Unlocking Advanced Strategies for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uskoković, V.; Hoover, C.; Vukomanović, M.; Uskoković, D.P.; Desai, T.A. Osteogenic and Antimicrobial Nanoparticulate Calcium Phosphate and Poly-(d,l-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Powders for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 3362–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhshani, A.; Maghsoudian, S.; Motasadizadeh, H.; Fatahi, Y.; Malek-Khatabi, A.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R. Synergistic Effects of Doxorubicin PLGA Nanoparticles and Simvastatin Loaded in Silk Films for Local Treatment of Breast Cancer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 104, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, N.; Cao, L.; Liu, H.; Cheng, H.; Ma, H.; Li, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, X.; et al. Quaternized Chitosan-Coated PLGA Nanoparticles Co-Deliver Resveratrol and All-Trans Retinoic Acid to Enhance Humoral Immunity, Cellular Immunity and Gastrointestinal Mucosal Immunity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 256, 114994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puricelli, C.; Gigliotti, C.L.; Stoppa, I.; Sacchetti, S.; Pantham, D.; Scomparin, A.; Rolla, R.; Pizzimenti, S.; Dianzani, U.; Boggio, E.; et al. Use of Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid Nano and Micro Particles in the Delivery of Drugs Modulating Different Phases of Inflammation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Bračko, I.; Milenković, M.; Filipović, N.; Nunić, J.; Filipič, M.; Uskoković, D.P.D.P. Multifunctional PLGA Particles Containing Poly(l-Glutamic Acid)-Capped Silver Nanoparticles and Ascorbic Acid with Simultaneous Antioxidative and Prolonged Antimicrobial Activity. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Lei, C. The Delivery and Activation of Growth Factors Using Nanomaterials for Bone Repair. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L. Co-Encapsulation of Combinatorial Flavonoids in Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles for Improved Anti-Osteoporotic Activity in Ovariectomized Rats. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Park, G.Y.; Oh, K.T.; Oh, N.M.; Kwag, D.S.; Youn, Y.S.; Oh, Y.T.; Park, J.W.; Lee, E.S. Multifunctional Poly (Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles for Luminescence/Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 434, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operti, M.C.; Bernhardt, A.; Grimm, S.; Engel, A.; Figdor, C.G.; Tagit, O. PLGA-Based Nanomedicines Manufacturing: Technologies Overview and Challenges in Industrial Scale-Up. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 605, 120807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadasan, D.; Sultan, M.H.; Madkhali, O.; Almoshari, Y.; Thangavel, N. Polymeric Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles (PLNs) as Emerging Drug Delivery Platform—A Comprehensive Review of Their Properties, Preparation Methods, and Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Li, J.; Song, T. Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid-Based Nanoparticles as Delivery Systems for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 973666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Shen, S.; Liu, H. Recent Advances in PLGA Micro/Nanoparticle Delivery Systems as Novel Therapeutic Approach for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 941077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Polymers Blending as Release Modulating Tool in Drug Delivery. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 752813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Savić, J.; Jordović, B.; Uskoković, D. Fabrication, in Vitro Degradation and the Release Behaviours of Poly(Dl-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanospheres Containing Ascorbic Acid. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 59, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, D.; Koithan, J.A.; Muliana, A.H.; Pharr, M. Effect of Mechanical Loading on PLGA Biodegradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 240, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, M.A.; Warunek, J.J.P.; Ravikumar, T.; Balmert, S.C.; Little, S.R. End Group Chemistry Modulates Physical Properties and Biomolecule Release from Biodegradable Polyesters. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 10621–10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N.; Yameen, B.; Wu, J.; Farokhzad, O.C. Degradable Controlled-Release Polymers and Polymeric Nanoparticles: Mechanisms of Controlling Drug Release. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2602–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, T.M.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, D.-S.; Baek, S.-W.; Bedair, H.M.; Joshi, H.P.; Choi, U.Y.; Park, K.-H.; Park, W.; Han, I.; et al. Magnesium Hydroxide-Incorporated PLGA Composite Attenuates Inflammation and Promotes BMP2-Induced Bone Formation in Spinal Fusion. J. Tissue Eng. 2020, 11, 2041731420967591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Uskoković, V.; Filipović, M.; Škapin, S.D.S.D.; Uskoković, D. Composite PLGA/AgNpPGA/AscH Nanospheres with Combined Osteoinductive, Antioxidative, and Antimicrobial Activities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 9034–9042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, M.J.; Loureiro, J.A.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Pereira, M.C. Factorial Design as a Tool for the Optimization of PLGA Nanoparticles for the Co-Delivery of Temozolomide and O6-Benzylguanine. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Braatz, R.D. A Mechanistic Model for Drug Release in PLGA Biodegradable Stent Coatings Coupled with Polymer Degradation and Erosion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford Versypt, A.N.; Pack, D.W.; Braatz, R.D. Mathematical Modeling of Drug Delivery from Autocatalytically Degradable PLGA Microspheres—A Review. J. Control. Release 2013, 165, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, K. The Prediction of the In Vitro Release Curves for PLGA-Based Drug Delivery Systems with Neural Networks. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanpour, S.; Amiriara, H.; Esfandyari-Manesh, M.; Ebrahimnejad, P.; Jeelani, H.; Henschel, A.; Singh, H.; Dinarvand, R.; Hassan, S. Utilizing Machine Learning for Predicting Drug Release from Polymeric Drug Delivery Systems. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 188, 109756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Yan, M.; Liu, C.; Du, B. Core–Shell Nanoparticles with Sequential Drug Release Depleting Cholesterol for Reverse Tumor Multidrug Resistance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 6689–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Park, C.; Sung, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. Peptide-Harnessed Supramolecular and Hybrid Nanomaterials for Stimuli-Responsive Theranostics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 539, 216737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makharadze, D.; del Valle, L.J.; Katsarava, R.; Puiggalí, J. The Art of PEGylation: From Simple Polymer to Sophisticated Drug Delivery System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Yi, Y.; Yu, Y. Effect of Partial PEGylation on Particle Uptake by Macrophages. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavimandi, F.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, M.; Shin, K. Beyond PEGylation: Nanoparticle Surface Modulation for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Health Nanotechnol. 2025, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graván, P.; Peña-Martín, J.; de Andrés, J.L.; Pedrosa, M.; Villegas-Montoya, M.; Galisteo-González, F.; Marchal, J.A.; Sánchez-Moreno, P. Exploring the Impact of Nanoparticle Stealth Coatings in Cancer Models: From PEGylation to Cell Membrane-Coating Nanotechnology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Chong, K.; Cui, M.; Cao, Z.; Tang, C.; Tian, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, S. Recent Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Safety Concerns for MRNA Delivery. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedl, J.D.; Nele, V.; De Rosa, G.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Bioinert, Stealth or Interactive: How Surface Chemistry of Nanocarriers Determines Their Fate In Vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleher, S.; Buck, J.; Muhl, C.; Sieber, S.; Barnert, S.; Witzigmann, D.; Huwyler, J.; Barz, M.; Süss, R. Poly(Sarcosine) Surface Modification Imparts Stealth-Like Properties to Liposomes. Small 2019, 15, 1904716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasanayake, G.S.; Hamadani, C.M.; Singh, G.; Kumar Misra, S.; Vashisth, P.; Sharp, J.S.; Adhikari, L.; Baker, G.A.; Tanner, E.E.L. Imidazolium-Based Zwitterionic Liquid-Modified PEG–PLGA Nanoparticles as a Potential Intravenous Drug Delivery Carrier. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 5584–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kankala, R.K.; Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Xie, S.; Li, H.; Chen, A.-Z.; Zou, L. Antibody-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Prospects. Theranostics 2022, 12, 3719–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayol, B.; Qubbaj, I.Z.; Nava-Granados, J.; Vasquez, K.; Keene, S.T.; Sempionatto, J.R. Aptamer and Oligonucleotide-Based Biosensors for Health Applications. Biosensors 2025, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, A.; Donno, R.; Gennari, A.; Cibecchini, G.; Catalano, F.; Marotta, R.; Pompa, P.P.; Tirelli, N.; Bardi, G. CXCL12-PLGA/Pluronic Nanoparticle Internalization Abrogates CXCR4-Mediated Cell Migration. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribovski, L.; Pincela Lins, P.M.; Moreira, B.J.; Antonio, L.C.; Cancino-Bernardi, J.; Zucolotto, V. Boosted Breast Cancer Treatment with Cell Membrane-Coated PLGA Nanocarriers: Investigating the Interactions with Various Cell Types. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 177, 214420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porello, I.; Bono, N.; Candiani, G.; Cellesi, F. Advancing Nucleic Acid Delivery through Cationic Polymer Design: Non-Cationic Building Blocks from the Toolbox. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 2800–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Malviya, R.; Kaushik, N. Chitosan in Biomedicine: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 8, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.; Maharjan, R.; Kim, N.A.; Jeong, S.H. New Long-Acting Injectable Microspheres Prepared by IVL-DrugFluidicTM System: 1-Month and 3-Month in Vivo Drug Delivery of Leuprolide. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 622, 121875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, A. Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Microsphere Production Based on Quality by Design: A Review. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1342–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendeman, S.P.; Shah, R.B.; Bailey, B.A.; Schwendeman, A.S. Injectable Controlled Release Depots for Large Molecules. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvantalab, S.; Drude, N.I.; Moraveji, M.K.; Güvener, N.; Koons, E.K.; Shi, Y.; Lammers, T.; Kiessling, F. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lababidi, J.M.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Revamping Parkinson’s Disease Therapy Using PLGA-Based Drug Delivery Systems. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, H.O.; Alharbi, F.D.; Alhibs, A.S.; Alanazi, N.B.; Alshehri, B.Y.; Saleh, M.A.; Alshehri, F.S.; Algarni, M.A.; Almugaiteeb, T.; Uddin, M.N.; et al. PLGA-Based Nanomedicine: History of Advancement and Development in Clinical Applications of Multiple Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanpour, S.; Tavatoni, P.; Akrami, M.; Navaei-Nigjeh, M.; Shiri, P. Potential Wound Healing of PLGA Nanoparticles Containing a Novel L-Carnitine–GHK Peptide Conjugate. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 6165759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Niu, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, A. Properties of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) and Progress of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)-Based Biodegradable Materials in Biomedical Research. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Aparicio-Blanco, J. Timeline of Translational Formulation Technologies for Cancer Therapy: Successes, Failures, and Lessons Learned Therefrom. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Wan, F.; Bera, H.; Cun, D.; Rantanen, J.; Yang, M. Quality by Design Thinking in the Development of Long-Acting Injectable PLGA/PLA-Based Microspheres for Peptide and Protein Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 585, 119441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.F.; Pinto, R.M.A.; Simões, S. Hot-Melt Extrusion in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Toward Filing a New Drug Application. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoubben, A.; Ricci, M.; Giovagnoli, S. Meeting the Unmet: From Traditional to Cutting-Edge Techniques for Poly Lactide and Poly Lactide-Co-Glycolide Microparticle Manufacturing. J. Pharm. Investig. 2019, 49, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Yang, M. Design of PLGA-Based Depot Delivery Systems for Biopharmaceuticals Prepared by Spray Drying. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 498, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, X.; Bodmeier, R. In Situ Forming Microparticle System for Controlled Delivery of Leuprolide Acetate: Influence of the Formulation and Processing Parameters. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 27, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xie, S.; Li, Z.; Dong, S.; Teng, L. Precise Nanoscale Fabrication Technologies, the “Last Mile” of Medicinal Development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2372–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bostami, R.D.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Husseini, G.A. Recent Advances in Nanoparticle-Based Co-Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tanani, M.; Satyam, S.M.; Rabbani, S.A.; El-Tanani, Y.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Al Faouri, I.; Rehman, A. Revolutionizing Drug Delivery: The Impact of Advanced Materials Science and Technology on Precision Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Yadav, K.S. Next-Gen Cancer Therapy: The Convergence of Artificial Intelligence, Nanotechnology, and Digital Twin. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 8, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.; Carter, E.J.; Mitchell, D.K.; Turner, J.P. Design and Evaluation of PLGA-Based Nanocarriers for Targeted and Sustained Drug Delivery in Vascular Disorders. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.S.; Repetto, T.; Burkhard, K.M.; Tuteja, A.; Mehta, G. Co-Delivery Polymeric Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) Nanoparticles to Target Cancer Stem-Like Cells. In Cancer Stem Cells; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, M.J.; Torres, I.D.; Loureiro, J.A.; Lima, J.; Pereira, M.C. Transferrin-Conjugated PLGA Nanoparticles for Co-Delivery of Temozolomide and Bortezomib to Glioblastoma Cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 14191–14203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Muhammad, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, W. Inflammation-Modulating Polymeric Nanoparticles: Design Strategies, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Applications. eBioMedicine 2025, 118, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.; Liu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Shi, Z.; Pan, X. Biodegradable Medical Implants: Reshaping Future Medical Practice. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e08014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Lei, Y.; Islam, R.; Tan, S.; Tong, R.; Miao, Y.-B.; Cai, L. Smart Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Padrela, L. Progress on Drug Nanoparticle Manufacturing: Exploring the Adaptability of Batch Bottom-up Approaches to Continuous Manufacturing. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 111, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csóka, I.; Ismail, R.; Jójárt-Laczkovich, O.; Pallagi, E. Regulatory Considerations, Challenges and Risk-Based Approach in Nanomedicine Development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 7461–7476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.; Lee, I.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, H. Ethical and Legal Challenges in Nanomedical Innovations: A Scoping Review. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1163392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Huang, X.; Xue, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, K. Advances in Medical Devices Using Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology: Innovation and Regulatory Science. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 48, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fabrication Strategy | Brief Description | Advantages | Limitations | Recent Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emulsion (Oil-in-Water, O/W) | PLGA and hydrophobic drug dissolved in an organic solvent → emulsified into aqueous surfactant phase → solvent evaporation to form nanoparticles. | Widely used for hydrophobic drugs; relatively simple. | Less suitable for hydrophilic drugs; possible residual solvent; broad size distribution. | Description of PLGA NP methods [53]. |

| Double Emulsion (Water-in-Oil-in-Water, W/O/W) | Aqueous solution of hydrophilic cargo emulsified in organic PLGA solution, then re-emulsified in aqueous phase, followed by solvent evaporation. | Better for hydrophilic biomolecules (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids). | More complex, possible instability or loss of cargo; higher PDI. | Example: BMP-2 loaded PLGA NPs via W/O/W [54]. |

| Nanoprecipitation (Solvent Displacement) | PLGA and drug in a water-miscible organic solvent are rapidly mixed into the aqueous phase → polymer precipitates forming nanoparticles. | Simpler process; good for hydrophobic drugs; potential for relatively small particles. | Control of mixing is critical; batch-to-batch reproducibility can suffer; less suitable for large biomolecules. | Enhanced nanoprecipitation method (2025) [55]. |

| Microfluidics-Assisted Production | Use of microfluidic mixers or microreactors to precisely control mixing of polymer/drug and aqueous phases, enabling reproducible and uniform nanoparticle formation. | Excellent control of size, PDI; better reproducibility; scalable potential. | Requires specialised equipment; scaling up may require parallelisation; cost may be higher. | Modular microfluidic system for PLGA NP encapsulating proteins [56]. Also, an ultrasonic microreactor for PLGA NPs [57]. |

| Spray Drying/Spray-Freeze Drying | Suspension of PLGA nanoparticles or microparticles is sprayed through hot air or frozen, then dried to form dry powder formulations. | Good for dry powder products, long-acting systems, and inhalable forms. | Heat or stress may degrade sensitive cargo; particle size control may be less precise than microfluidic methods. | Discussed in the implant/fabrication review context [58]. |

| Electrospraying/Electrospray | Polymer/drug solution is ejected under a high electric field to form fine droplets, which solidify into particles. | Good for precise size control, high encapsulation potential, and suitable for sensitive cargo. | Lower throughput; technical setup complex; fewer examples in PLGA drug delivery compared to emulsion/nanoprecipitation. | Emerging method for polymeric particle synthesis (polymeric particle optimisation) [59]. |

| Composition | Typical Structure/How It Is Made | Payload Types Suited | Key Advantages | Key Limitations/Risks | Representative Recent Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid–PLGA core–shell | PLGA core (drug) with lipid shell (adsorbed/anchored nucleic acid or hydrophilic cargo); made by single-step nanoprecipitation + lipid coating or double emulsion + lipid assembly | Hydrophobic small molecules in core; mRNA/siRNA, proteins or adjuvants at/within shell | Spatial segregation for incompatible cargos; improved colloidal stability and membrane-mimetic interactions (better cell uptake) | Potential complexity in scale-up; shell detachment in vivo; stability of nucleic acids on/near surface. | [107,108] |

| Compartmentalised/multi-core (double emulsion, multicore) | Multiple aqueous/oil compartments (w/o/w) or multi-core droplets created by double emulsion or multi-phase nanoprecipitation | Hydrophilic (proteins, nucleic acids) + hydrophobic drugs simultaneously | Good separation of chemically incompatible payloads; tunable sequential release | Emulsion complexity; lower encapsulation efficiency for some cargos; reproducibility at scale. | [53,109] |

| Polymer–polymer blends/block co-polymers (PLGA–PEG, PLGA–PCL) | Physical blends or block copolymers formed during nanoprecipitation or solvent evaporation | Hydrophobic drugs, some proteins (with stabilisation) | Tuning of degradation and release kinetics; PEG improves stealth; simpler fabrication than multi-compartment systems | Phase separation risks; balancing hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity for dual payloads can be tricky. | [110] |

| Inorganic–PLGA hybrids (magnetic, gold, QDs, hydroxyapatite) | Inorganic core or embedded particles within the PLGA matrix, formed by co-encapsulation or surface adsorption | Imaging agents (iron oxide, QD), photothermal agents + chemotherapeutics, mineral–bonded fluorescent dye | Adds imaging/theranostic functionality; allows guided delivery or PTT/PDT, detection of degradation process | Added regulatory/toxicity burden for inorganic material; possible altered degradation and clearance. | [23,32] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stevanović, M.M.; Qian, K.; Huang, L.; Vukomanović, M. PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Nanoformulations: Overview, Strategies, and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121613

Stevanović MM, Qian K, Huang L, Vukomanović M. PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Nanoformulations: Overview, Strategies, and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121613

Chicago/Turabian StyleStevanović, Magdalena M., Kun Qian, Lin Huang, and Marija Vukomanović. 2025. "PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Nanoformulations: Overview, Strategies, and Recent Advances" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121613

APA StyleStevanović, M. M., Qian, K., Huang, L., & Vukomanović, M. (2025). PLGA-Based Co-Delivery Nanoformulations: Overview, Strategies, and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121613