Oral Treatment of Obesity by GLP-1 and Its Analogs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Physiology of Adipose Tissue and Pathophysiology of Obesity

1.2. Treatments of Obesity

1.2.1. Bariatric and Metabolic Procedures

1.2.2. Pharmacotherapy

1.3. Physiology of GLP-1

1.3.1. Systemic Effects of GLP-1: From Physiology to Pharmacology

1.3.2. Regulation of GLP-1 Expression

1.3.3. GLP-1 Receptor (GLP-1R)

1.3.4. Degradation of GLP-1

1.3.5. Incretin Effect: Regulation of the Postprandial GLP-1 Secretion

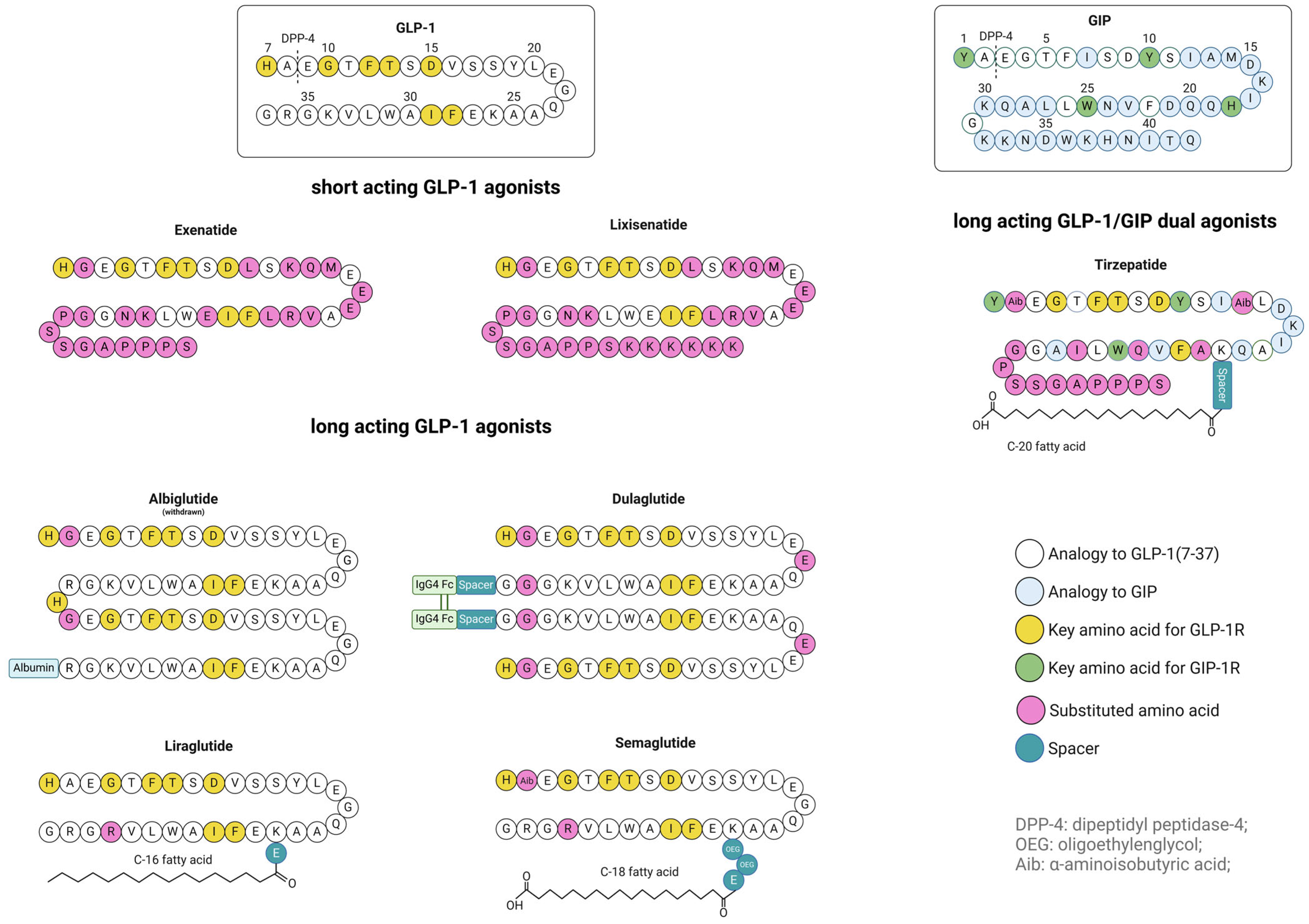

2. Approved GLP-1 Analogs

| Peptide | MW | pI | DPP-4 Susceptibility | Additional Modifications to Peptide Backbone (linker) | Product (Approval Year) | Half-Life | Approved Dosages | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 (7–36) amide | 3297.6 Da | - (1) | rapid degradation | - | - | 1–2 min | - | [54,127] |

| Exenatide | 4186.6 Da | 4.86 | Ala8→Gly substitution | - | Byetta® 2005 Bydureon® 2012 | 2.4 h | s.c.: 5/10 µg | [105,128] |

| Lixisenatide | 4858.5 Da | 9.5 | Ala8→Gly substitution | - | Lyximia® 2013 Adlyxin® 2016 | 3 h | s.c.: 10/20 μg | [110,111] |

| Liraglutide | 4813.5 Da | 4.9 | steric hindrance | Lys26: C16 (via γGlu) | Victoza® 2010 Saxenda ® 2015 | ~13 h | s.c.: 0.6/1.2/1.8 mg; (Saxenda: additional dosages 2.4/3.0 mg) | [43,129] |

| Semaglutide | 4113.6 Da | 5.4 | Ala8→Aib substitution | Lys34: C18 (via γGlu-2xOEG) | Ozempic® 2017 Rybelsus® 2017 | ~1 week | s.c.: 0.25/0.5/1/2 mg; oral: R1 3/7/14 mg/R2 1.5/4/9 mg (2) | [46,47,130,131] |

| Dulaglutide | ~63 kDa | - (1) | Ala8→Gly substitution | Gly37: Fc-region of IgG4 (via G7SG4SG linker) | Trulicity® 2014 | ~5 days | s.c.: 0.75/1.5/3/4.5 mg | [120] |

| Albiglutide | ~73 kDa | - (1) | Ala8→Gly substitution | Arg36: albumin | Eperzan® 2014 (withdrawn) | ~5 days | s.c.: 30/50 mg | [100] |

| Tirzepatide | 4813.5 Da | - (1) | Ala8→Aib substitution | Lys26: C20 (via γGlu-Ado-Ado linker) | Mounjaro® 2022 Zepbound® 2022 | ~5 days | s.c.: 2.5/5/7.5/10/12.5/15 mg | [53] |

3. GLP-1 Analogs in Clinical Trials for Treatment of Obesity

3.1. GLP-1- and GIP-Receptor Co-Agonists

3.2. GLP-1/Glucagon Receptors Co-Agonists (GLP-1R/GCGR Co-Agonists)

3.3. GLP-1/GIP/Glucagon Receptors Co-Agonists (GLP-1R/GIPR/GCGR Co-Agonists)

3.4. Other Combinations with GLP-1R Agonists

3.5. Small-Molecule Drugs

3.6. Peptides vs. Small-Molecule Drugs

- (1)

- Multiple receptors targeting: This strategy involves the peptide drugs which are binding two or more (usually incretin) GPCRs. The rational peptide design and the conserved key residues within binding pockets of GPCRs both enable that a created peptide molecule or peptide conjugate bind specifically to multiple targets at once [152]. Since all of the abovementioned incretin mimetics are agonists to GPCRs, this kind of poly-pharmacology will be very attractive for their future drug development [81].

- (2)

- Biased signaling: Some GLP-1-biased agonists mentioned above, such as orforglipron and danuglipron, activate a biased signal cascade, in which GPCR binds preferentially or almost exclusively to G-protein instead to another associated effector protein, in this case, concretely with the ß-arrestin 2. In this manner, the GLP-1 receptor internalization can be avoided. This concept offers the possibility of selecting the signaling pathway, which will have an increased therapeutic effect, while the undesired downstream signal cascades and consequent side-effects could be minimalized [81]. However, it is important to note that biased signaling can be achieved with peptide analogs as well, and that small-molecule drugs potentially show less receptor specificity than peptide analogs [153].

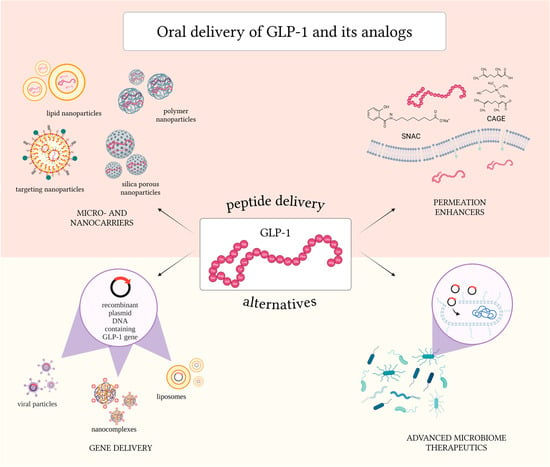

4. Challenges and Strategies to Overcome the Physiological Barriers in Oral Delivery of GLP-1 and GLP-1 Analogs

5. Permeation Enhancers for the Oral Delivery of GLP-1 and Its Analogs

5.1. SNAC (Sodium N-[8-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)amino]caprylate)

5.2. Chitosan

5.3. Medium-Chain Fatty Acids (MCFAs)

5.4. Ionic Liquids

6. Micro- and Nanocarriers for Oral Delivery of GLP-1 and Its Analogs

6.1. Active Targeting Mechanisms in Oral Delivery via Micro- and Nanocarriers

6.1.1. FcRn Targeting

6.1.2. Transferrin Receptor Targeting

6.1.3. Targeting Goblet Cells

6.1.4. Other Targets

6.2. Microparticles of Different Types

6.3. PLA and PLGA Nanoparticles

6.4. Chitosan Nanoparticles

6.5. Silica Nanoparticles

6.6. Lipid-Based Nanoformulations and Liposomes

6.7. Various Special Nanoparticles

- Protamine Nanoparticles

- Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles

- Metal Organic Framework Nanoparticles

- Zein Nanoparticles

- Milk Exosomes

- Aminoclay Nanoparticles

- Bile Acid Nanoparticles

7. Gene-Based Delivery of GLP-1

8. Microbiota for GLP-1 Delivery and In Situ Secretion

8.1. Advanced Microbiome Therapeutics (AMTs)

8.1.1. Challenges for Oral Peptide Delivery with AMTs

8.1.2. AMTs for Delivery of GLP-1 and Its Analogs

9. Safety Studies and Misuse of GLP-1 Analogs

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-CNAC | 8-(N-2-hydroxy-5-chlorobenzoyl)-amino-caprylic acid |

| ABHD12 | αβ-hydrolase 12 |

| Aib | aminoisobutyric acid |

| AMT(s) | advanced microbiome therapeutic(s) |

| ASBT(s) | apical sodium bile acid transporter(s) |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| BAT | brown adipose tissue |

| BMI | body mass index |

| bPEI | branched polyethyleneimine |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| C/EBPs | CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins |

| C10 | sodium caprate |

| C8 | sodium caprylate |

| CAGE | choline and geranic acid |

| CHONAC | choline salcaprozate |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| COM NP(s) | complexed nanoparticle(s) |

| CPP(s) | cell penetrating peptide(s) |

| CV | cardiovascular |

| CYP | cytochrome P450 |

| DAGL | diacylglycerol lipase |

| DC | deoxycholate |

| DDM | n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside |

| DEX | dextran |

| DIS NP(s) | dispersed nanoparticle(s) |

| DLPC | dilauroyl phosphatidylcholine |

| DMG-PEG | 1,2-dimyristoyl-rac-glycero-3-methoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-200 |

| DOC | sodium docusate |

| DPP-4 | dipeptidylpeptidase-4 |

| DPPC | dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DSPE | 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine |

| DSPE-Hyd-PMPC | 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine-hydrazone bond-poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) |

| EBMTs | endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies |

| ECD | extracellular domain |

| ECL | extracellular loop |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FA | folic acid |

| Fc region | fragment crystallizable region |

| FcRn | neonatal Fc receptor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GCA | glycocholic acid |

| Gcg | preproglucagon-gene |

| GCGR | glucagon receptor |

| GIP | glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GIPR | glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor |

| GI-tract | gastrointestinal tract |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GLP-1R | glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor |

| GLP-2 | glucagon-like peptide 2 |

| GPCRs | G-protein coupled receptors |

| GRAS | generally regarded as safe |

| GRK2 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 |

| HA | hyaluronic acid |

| HPMC | hydroxypropyl methylcellulose |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| IL(s) | ionic liquid(s) |

| INCL | intracellular loop |

| KLF(s) | kruppel-like transcription factor(s) |

| KO mice | knock-out mice |

| LAB | lactic acid bacteria |

| LDC | lysine conjugated deoxycholic acid |

| LMWP | low molecular weight protamine |

| LNC(s) | lipid nanocapsule(s) |

| lPEI | linear polyethylenimine |

| MASH | metabolic associated steatohepatitis |

| MC4R | melanocortin-4 receptor |

| MCFA(s) | medium-chain fatty acid(s) |

| MCT(s) | medium-chain triglyceride(s) |

| MOF | metal organic framework |

| MP(s) | microparticle(s) |

| NLC(s) | nanostructured lipid carrier(s) |

| NP(s) | nanoparticle(s) |

| NTCP(s) | sodium/taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide(s) |

| NTS | nucleus of the solitary tract |

| OGT | oral glucose test |

| PC | prohormone convertase |

| PCFT | proton-coupled folate transporter |

| PE(s) | permeation enhancer(s) |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha |

| pHPMA | poly-N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PLGA | poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) |

| PPAR-γ | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma |

| PRDM16 | PR domain containing 16 |

| PSi nanoparticles | porous silicon nanoparticles |

| PYY | peptide YY |

| RM(s) | reverse micelle(s) |

| RYGB | Roux-Y gastric bypass |

| SEDDS(s) | self-emulsifying drug delivery system(s) |

| SG | sleeve gastrectomy |

| SIP | structure inducing probe |

| SLN(s) | solid lipid nanoparticle(s) |

| SNAC | sodium N-[8-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)amino]caprylate |

| SOS | sodium n-octadecyl sulfate |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Tf | transferrin |

| TfR | transferrin receptor |

| THA | tetraheptylammonium bromide |

| TLC | taurolithocholate |

| TMC | trimethyl chitosan |

| TMD | transmembrane domain |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor α |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

| WHO | World health organization |

| ZDF | Zucker diabetic fatty |

| γGlu-2xOEG | γ-Glutamyl-bis(oligoethylene glycol), γ-Glutamyl-bis(oligoethylene glycol) |

| γ-PGA | poly(γ-glutamic acid) |

References

- WHO. New WHO/Europe Fact Sheet Highlights Worrying Post-COVID Trends in Childhood Obesity. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/29-11-2024-new-who-europe-fact-sheet-highlights-worrying-post-covid-trends-in-childhood-obesity (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Ha, S.; Lau, H.C.H.; Yu, J. Excess body weight: Novel insights into its roles in obesity comorbidities. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 92, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. One in Eight People Are Now Living with Obesity. Volume 45. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-03-2024-one-in-eight-people-are-now-living-with-obesity (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Novelli, G.; Cassadonte, C.; Sbraccia, P.; Biancolella, M. Genetics: A Starting Point for the Prevention and the Treatment of Obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, B.J.; Hill, J.O.; Gunn, A.J. Obesity: Scope, Lifestyle Interventions, and Medical Management. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 23, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 706978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Duan, Y.; An, Y.; Shi, L.; Lv, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Ma, Q.; et al. Brown and beige adipose tissue: A novel therapeutic strategy for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adipocyte 2021, 10, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Frontini, A.; Cinti, S. Convertible visceral fat as a therapeutic target to curb obesity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner-Nedherer, A.L.; Fuchs, J.; Vidakovic, I.; Höller, O.; Schratter, G.; Almer, G.; Fröhlich, E.; Zimmer, A.; Wabitsch, M.; Kornmueller, K.; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles as a Shuttle for Anti-Adipogenic miRNAs to Human Adipocytes. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.J.; Perfetti, T.A.; Wallace Hayes, A.; Berry, S.C. Obesity as a source of endogenous compounds associated with chronic disease: A review. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 175, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusminski, C.M.; Bickel, P.E.; Scherer, P.E. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melson, E.; Ashraf, U.; Papamargaritis, D.; Davies, M.J. What is the pipeline for future medications for obesity? Int. J. Obes. 2024, 49, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipek, L.Z.; Moraes, W.A.F.; Nobetani, R.M.; Cortez, V.S.; Condi, A.S.; Taba, J.V.; Nascimento, R.F.V.; Suzuki, M.O.; do Nascimento, F.S.; de Mattos, V.C.; et al. Surgery is associated with better long-term outcomes than pharmacological treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Brown -Chair, W.; Kow, L.; Mehran Anvari, A.; Amir Ghaferi, C.; John Morton, U.; Scott Shikora, U.; Ronald Liem, U.; Himpens, J.; Mario Musella, B.; Francois Pattou, I.; et al. 8-th Global Registry Report of the IFSO Global Registry Committee. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifso.com/pdf/8th-ifso-registry-report-2024-latest-new.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Mingrone, G.; Rajagopalan, H. Bariatrics and endoscopic therapies for the treatment of metabolic disease: Past, present, and future. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 211, 111651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagneto Gissey, L.; Casella Mariolo, J.; Mingrone, G. Intestinal peptide changes after bariatric and minimally invasive surgery: Relation to diabetes remission. Peptides 2018, 100, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirapinyo, P.; Hadefi, A.; Thompson, C.C.; Patai, Á.V.; Pannala, R.; Goelder, S.K.; Kushnir, V.; Barthet, M.; Apovian, C.M.; Boskoski, I.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Endoscopy 2024, 56, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhe, I.; Douissard, J.; Podetta, M.; Chevallay, M.; Toso, C.; Jung, M.K.; Meyer, J. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or one-anastomosis gastric bypass? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Obesity 2022, 30, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, F.; Negrão, M.G.; Negrão, G.G. Weight loss comparison after sleeve and roux-en-y gastric bypass: Systematic review. Abcd-Arquivos Bras. Cir. Dig. Arch. Dig. Surg. 2019, 32, e1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Plank, L.D.; Clarke, M.G.; Evennett, N.J.; Tan, J.; Kim, D.D.W.; Cutfield, R.; Booth, M.W.C. Effect of Banded Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy on Diabetes Remission at 5 Years Among Patients With Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieder, J.S.; Montorfano, L.; Gomez, C.O.; Aleman, R.; Okida, L.F.; Ferri, F.; Funes, D.R.; Lo Menzo, E.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.J. Sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients Aged ≥ 65 years: A comparison of short-term outcomes. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Friedman, J.; Park, H.; Segal, R.; Brumback, B.; Hartzema, A. Comparative Safety of Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y: A Propensity Score Analysis. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 2715–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilingiris, D.; Kokkinos, A. Advances in obesity pharmacotherapy; learning from metabolic surgery and beyond. Metabolism 2024, 151, 155741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, M.; Soós, S.; Pétervári, E.; Balaskó, M. Nutritional Impact on Anabolic and Catabolic Signaling. In Molecular Basis of Nutrition and Aging: A Volume in the Molecular Nutrition Series; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.H.; Gudzune, K.A.; Ard, J.D. Phentermine in the Modern Era of Obesity Pharmacotherapy: Does It Still Have a Role in Treatment? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. 2024. Available online: www.fda.gov/drugsatfda (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- EMA—Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC). Withdrawal of Marketing Authorisations for Amfepramone Medicines Within the EU. EMA/867253/2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/amfepramone-containing-medicinal-products (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Contrave: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-22. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/200063s022lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Assessment Report—Qsiva. 2013. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/qsiva-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Qsymia: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—ORIG-1. 2012. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022580s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EMA—Human Medicines Evaluation Division. Phentermine/topiramate: PSUSA/00010956/202307—Periodic Safety Update Report Single Assessment. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/psusa/psusa-00010956-202307 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). EMA Starts Review of Weight Management Medicine Mysimba. 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/mysimba-article-20-procedure-ema-starts-review-weight-management-medicine-mysimba_en.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Assessment Report—Mysimba. 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/mysimba-h-20-1530-c-3687-0065-epar-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Cignarella, A.; Busetto, L.; Vettor, R. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: An update. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 169, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessell, E.; Maunder, A.; Lauche, R.; Adams, J.; Sainsbury, A.; Fuller, N.R. Efficacy of dietary supplements containing isolated organic compounds for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musaimi, O. Exploring FDA-Approved Frontiers: Insights into Natural and Engineered Peptide Analogues in the GLP-1, GIP, GHRH, CCK, ACTH, and α-MSH Realms. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Santen, H.M.; Denzer, C.; Müller, H.L. Could setmelanotide be the game-changer for acquired hypothalamic obesity? Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1307889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Munoz, C.M.; López, M.; Albericio, F.; Makowski, K. Targeting energy expenditure—Drugs for obesity treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Assessment Report—Imcivree. 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/imcivree-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Urano, F. Wolfram Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Saxenda: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-19. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/206321s019lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Victoza: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-46. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2025/022341s046lbl.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Wegovy: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-15. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/215256s015lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Ozempic: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-32. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/209637s032lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Rybelsus: FDA approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-23. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/213051s023lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Rybelsus: FDA approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-21. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2025/213051Orig1s020,213051Orig1s021lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Rybelsus—Product Information. 2024 Nov. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rybelsus-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- European Commission. Union Register of Medicinal Products—Public Health—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/h1430.htm (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Mounjaro—Product Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/mounjaro-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Meeting Highlights from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/meeting-highlights-committee-medicinal-products-human-use-chmp-9-12-december-2024 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Zepbound: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-13. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/217806s013lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Holst, J.J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Benjamin, M.M.; Srinivasan, S.; Morin, E.E.; Shishatskaya, E.I.; Schwendeman, S.P.; Schwendeman, A. Battle of GLP-1 delivery technologies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 130, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.; Drucker, D.J.; Flatt, P.R.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, H.J.; Habener, J.F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, C.; Donnelly, D.; Wootten, D.; Lau, J.; Sexton, P.M.; Miller, L.J.; Ahn, J.M.; Liao, J.; Fletcher, M.M.; Yang, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 and its class B G protein-coupled receptors: A long march to therapeutic successes. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 954–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buteau, J. GLP-1 receptor signaling: Effects on pancreatic β-cell proliferation and survival. Diabetes Metab. 2008, 34, S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J.J. GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, J.; Xiao, X.; Prasadan, K.; Sheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Ming, Y.C.; Gittes, G. GLP-1/Exendin-4 induces β-cell proliferation via the epidermal growth factor receptor. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu, M.; Yang, J.Y.; Jaccard, E.; Poussin, C.; Widmann, C.; Thorens, B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects β-cells against apoptosis by increasing the activity of an Igf-2/Igf-1 receptor autocrine loop. Diabetes 2009, 58, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, S.; Bertrand, G.; Ravier, M.A. Mechanisms of beta-cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes-prone situations and potential protection by glp-1-based therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ramracheya, R.; Lahmann, C.; Tarasov, A.; Bengtsson, M.; Braha, O.; Braun, M.; Brereton, M.; Collins, S.; Galvanovskis, J.; et al. Role of KATP channels in glucose-regulated glucagon secretion and impaired counterregulation in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørgaard, A.; Holst, J.J. The role of somatostatin in GLP-1-induced inhibition of glucagon secretion in mice. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramracheya, R.; Chapman, C.; Chibalina, M.; Dou, H.; Miranda, C.; González, A.; Moritoh, Y.; Shigeto, M.; Zhang, Q.; Braun, M.; et al. GLP-1 suppresses glucagon secretion in human pancreatic alpha-cells by inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Vella, A. Effects of GLP-1 on appetite and weight. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2014, 15, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, J.; Verbeure, W.; Mori, H.; Schol, J.; Van den Houte, K.; Huang, I.H.; Balsiger, L.; Broeders, B.; Colomier, E.; Scarpellini, E.; et al. The gastrointestinal tract in hunger and satiety signalling. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2021, 9, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.B.; Pyke, C.; Rasch, M.G.; Dahl, A.B.; Knudsen, L.B.; Secher, A. Characterization of the glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor in male mouse brain using a novel antibody and in situ hybridization. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Patrício, B.; Lioci, G.; Macedo, M.P.; Gastaldelli, A. Gut-pancreas-liver axis as a target for treatment of nafld/nash. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastel, E.; Joshi, S.; Knight, B.; Liversedge, N.; Ward, R.; Kos, K. Effects of Exendin-4 on human adipose tissue inflammation and ECM remodelling. Nutr. Diabetes 2016, 6, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zong, C.; Qin, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; et al. GLP-1/GLP-1R Signaling in Regulation of Adipocyte Differentiation and Lipogenesis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ren, J.; Song, J.; Liu, F.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Gong, L.; Li, W.; Xiao, F.; Yan, F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 regulates adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.J.; Henriksen, T.I.; Pedersen, B.K.; Solomon, T.P.J. Glucagon Like Peptide-1-Induced Glucose Metabolism in Differentiated Human Muscle Satellite Cells Is Attenuated by Hyperglycemia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subaran, S.C.; Sauder, M.A.; Chai, W.; Jahn, L.A.; Fowler, D.E.; Aylor, K.W.; Basu, A.; Liu, Z. GLP-1 at physiological concentrations recruits skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature in healthy humans. Clin. Sci. 2014, 127, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, A.; Asmar, M.; Simonsen, L.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Hartmann, B.; Sorensen, C.M.; Bülow, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 elicits vasodilation in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in healthy men. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alken, M.; Rutz, C.; Köchl, R.; Donalies, U.; Oueslati, M.; Furkert, J.; Wietfeld, D.; Hermosilla, R.; Scholz, A.; Beyermann, M.; et al. The signal peptide of the rat corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 promotes receptor expression but is not essential for establishing a functional receptor. Biochem. J. 2005, 390, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, D.A.; D’alessio, D.A. Physiology of Proglucagon Peptides: Role of Glucagon and GLP-1 in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, R.A.; O’Harte, F.P.M.; Irwin, N.; Gault, V.A.; Flatt, P.R. Proglucagon-Derived Peptides as Therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 689678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, C.; Bersani, M.; Johnsen, A.H.; Højrup, P.; Holst, J.J. Complete Sequences of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 from Human and Pig Small Intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 12826–12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreymann, B.; Williams, G.; Ghatei, M.A.; Bloom, S.R. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 7-36: A Physiological Incretin in Man. Lancet 1987, 330, 1300–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Xia, F.; Li, Z.; Shen, C.; Yang, Z.; Hou, H.; Sun, S.; Feng, Y.; Yong, X.; Tian, X.; et al. Structure, function and drug discovery of GPCR signaling. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couvineau, A.; Laburthe, M. The Family B1 GPCR: Structural Aspects and Interaction with Accessory Proteins. Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, S.R.J. Mechanisms of peptide and nonpeptide ligand binding to Class B G-protein-coupled receptors. Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.; Deacon, C.F.; Ørskov, C.; Holst, J.J. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-(7-36)Amide Is Transformed to Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-(9-36)Amide by Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV in the Capillaries Supplying the L Cells of the Porcine Intestine. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 5356–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C.F.; Johnsen, A.H.; Holst, J.J. Degradation of Glucagon-Like Peptide-l by Human Plasma in Vitro Yields an N-Terminally Truncated Peptide That Is a Major Endogenous Metabolite in Vivo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Yu, T.; Lee, D.H. The nonglycemic actions of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 368703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, L.B.; Pridal, L. Glucagon-like peptide-1-(9-36) amide is a major metabolite of glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36) amide after in vivo administration to dogs, and it acts as an antagonist on the pancreatic receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 318, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, A.P.; Sorrell, J.E.; Haller, A.; Roelofs, K.; Hutch, C.R.; Kim, K.S.; Gutierrez-Aguilar, R.; Li, B.; Drucker, D.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; et al. The Role of Pancreatic Preproglucagon in Glucose Homeostasis in Mice. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 927–934.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. Pancreatic GLP1 is involved in glucose regulation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balks, H.J.; Holst, J.J.; Mühlen, A.v.Z.; Brabant, G. Rapid Oscillations in Plasma Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) in Humans: Cholinergic Control of GLP-1 Secretion via Muscarinic Receptors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggio, L.L.; Drucker, D.J. Biology of Incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2131–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Rüdiger, G.; Richter, G.; Fehmann, H.-C.; Arnold, R.; Göke, B. BGlucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Glucose-Dependent Insulin-Releasing Polypeptide Plasma Levels in Response to Nutrients. Digestion 1994, 56, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Incretin hormones: Their role in health and disease. Vol. 20, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20 (Suppl. 1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilsbøll, T.; Krarup, T.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J. Both GLP-1 and GIP are insulinotropic at basal and postprandial glucose levels and contribute nearly equally to the incretin effect of a meal in healthy subjects. Regul. Pept. 2003, 114, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rask, E.; Olsson, T.; Oderberg, S.S.; Johnson, O.; Seckl, J.; Holst, J.J.; Ahrén, B.O. Impaired Incretin Response After a Mixed Meal Is Associated With Insulin Resistance in Nondiabetic Men. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, R.; Drucker, D.J. Beyond the pancreas: Contrasting cardiometabolic actions of GIP and GLP1. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 19, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbjerg, L.S.; Rasmussen, R.S.; Dragan, A.; Lindquist, P.; Melchiorsen, J.U.; Stepniewski, T.M.; Schiellerup, S.; Tordrup, E.K.; Gadgaard, S.; Kizilkaya, H.S.; et al. Altered desensitization and internalization patterns of rodent versus human glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors. An important drug discovery challenge. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 182, 3353–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaïmia, N.; Obeid, J.; Varrault, A.; Sabatier, J.; Broca, C.; Gilon, P.; Costes, S.; Bertrand, G.; Ravier, M.A. GLP-1 and GIP receptors signal through distinct β-arrestin 2-dependent pathways to regulate pancreatic β cell function. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikoff, A.; Müller, T.D. Pharmacological Advances in Incretin-Based Polyagonism: What We Know and What We Don’t. Physiology 2024, 39, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Tanzeum: FDA approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-20. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125431s020lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Eperzan—Product Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/eperzan-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- GlaxoSmithKline. Physician Notification Letter UK-Eperzan▼(Albiglutide): Global Discontinuation of Medicine. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/59f081c6e5274a18bc07411b/Eperzan_Letter_-_090917.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Engsbli, J.; Kleinmans, W.A.; Singhll, L.; Singhi, G.; Raufmanll, J.P. Isolation and characterization of exendin-4, an exendin-3 analogue, from Heloderma suspectum venom. Further evidence for an exendin receptor on dispersed acini from guinea pig pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 7402–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, S.; Schimmer, S.; Oschmann, J.; Schiødt, C.B.; Knudsen, S.M.; Jeppesen, C.B.; Madsen, K.; Lau, J.; Thøgersen, H.; Rudolph, R. Differential structural properties of GLP-1 and exendin-4 determine their relative affinity for the GLP-1 receptor N-terminal extracellular domain. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 5830–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Byetta: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-49. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/021773s049lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Bydureon BCise: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-24. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/209210s024lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Bydureon: FDA approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-35. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/022200s035lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Astra Zeneca. Report: Patent Expiries of Key Marketed Products 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/content/dam/az/Investor_Relations/annual-report-2023/pdf/AstraZeneca_Patent_Expiries_of_Key_Marketed_Products_2023.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Amneal Pharmaceuticals Inc. Press Release: Amneal Resubmits DHE Autoinjector New Drug Application and Receives U.S. FDA Approval of Exenatide, its First Generic Injectable GLP-1 Agonist. 2024. Available online: https://investors.amneal.com/news/press-releases/press-release-details/2024/Amneal-Resubmits-DHE-Autoinjector-New-Drug-Application-and-Receives-U.S.-FDA-Approval-of-Exenatide-its-First-Generic-Injectable-GLP-1-Agonist/default.aspx (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- EMA: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Lyximia—Product Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lyxumia-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Adlyxin: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-9. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/208471s009lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Christensen, M.; Miossec, P.; Larsen, B.D.; Werner, U.; Knop, F.K. The design and discovery of lixisenatide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2014, 9, 1223–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, C.; Pinto, S.; Benjakul, S.; Nilsen, J.; Santos, H.A.; Traverso, G.; Andersen, J.T.; Sarmento, B. Prevention of diabetes-associated fibrosis: Strategies in FcRn-targeted nanosystems for oral drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zou, T.; Kuang, T.; Wang, J. Research Advances in Fusion Protein-Based Drugs for Diabetes Treatment. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilati, D.; Howard, K.A. Albumin-based drug designs for pharmacokinetic modulation. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2020, 16, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.B.; Lau, J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Su, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sattler, M.; Zou, P. Albumin-binding domain extends half-life of glucagon-like peptide-1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 890, 173650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesner, W.; Vick, A.M.; Millican, R.; Ellis, B.; Tschang, S.H.; Tian, Y.; Bokvist, K.; Brenner, M.; Koester, A.; Porksen, N.; et al. Engineering and characterization of the long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue LY2189265, an Fc fusion protein. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2010, 26, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohl, W.R. Fusion Proteins for Half-Life Extension of Biologics as a Strategy to Make Biobetters. BioDrugs 2015, 29, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Trulicity: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—SUPPL-62. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/125469s061s062lbl.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Curry, S.; Brick, P.; Franks, N.P. Fatty Acid Binding to Human Serum Albumin: New Insights from Crystallographic Studies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1441, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Bloch, P.; Schäffer, L.; Pettersson, I.; Spetzler, J.; Kofoed, J.; Madsen, K.; Knudsen, L.B.; McGuire, J.; Steensgaard, D.B.; et al. Discovery of the Once-Weekly Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogue Semaglutide. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 7370–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.A.; Matthews, J.E.; De Boever, E.H.; Dobbins, R.L.; Hodge, R.J.; Walker, S.E.; Holland, M.C.; Gutierrez, M.; Stewart, M.W. Safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of albiglutide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetic, in healthy subjects. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2009, 11, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Mounjaro: FDA Approval—Prescribing Information—ORIG-1. 2022. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215866s000lbl.pdf?1fba97f6_page=3 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Coskun, T.; Sloop, K.W.; Loghin, C.; Alsina-Fernandez, J.; Urva, S.; Bokvist, K.B.; Cui, X.; Briere, D.A.; Cabrera, O.; Roell, W.C.; et al. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol. Metab. 2018, 18, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Willard, F.S.; Feng, D.; Alsina-Fernandez, J.; Chen, Q.; Vieth, M.; Ho, J.D.; Showalter, A.D.; Stutsman, C.; Ding, L.; et al. Structural Determinants of Dual Incretin Receptor Agonism by Tirzepatide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116506119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem. GLP-1. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Glucagon-Like-Peptide-1 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Tomono, T.; Yagi, H.; Ukawa, M.; Ishizaki, S.; Miwa, T.; Nonomura, M.; Igi, R.; Kumagai, H.; Miyata, K.; Tobita, E.; et al. Nasal absorption enhancement of protein drugs independent to their chemical properties in the presence of hyaluronic acid modified with tetraglycine-L-octaarginine. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 154, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Liraglutide. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/16134956 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Rybelsus: Product Quality Review(s). 2019. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/213051Orig1s000ChemR.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Pubchem. Semaglutide. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/56843331 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Goldenberg, R.M.; Gilbert, J.D.; Manjoo, P.; Pedersen, S.D.; Woo, V.C.; Lovshin, J.A. Management of type 2 diabetes, obesity, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with high-dose GLP-1 receptor agonists and GLP-1 receptor-based co-agonists. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véniant, M.M.; Lu, S.C.; Atangan, L.; Komorowski, R.; Stanislaus, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, B.; Falsey, J.R.; Hager, T.; Thomas, V.A.; et al. A GIPR antagonist conjugated to GLP-1 analogues promotes weight loss with improved metabolic parameters in preclinical and phase 1 settings. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Ryan, D.H.; Bays, H.E.; Ebeling, P.R.; Mackowski, M.G.; Philipose, N.; Ross, L.; Liu, Y.; Burns, C.E.; Abbasi, S.A.; et al. Once-Monthly Maridebart Cafraglutide for the Treatment of Obesity—A Phase 2 Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikoff, A.; Müller, T.D. Antagonizing GIPR adds fire to the GLP-1R flame. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 35, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, E.A.; Chen, M.; Falsey, J.R.; Sivits, G.; Hager, T.; Atangan, L.; Helmering, J.; Lee, J.; Li, H.; Wu, B.; et al. Chronic glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism desensitizes adipocyte GIPR activity mimicking functional GIPR antagonism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkilde, M.M.; Lindquist, P.; Kizilkaya, H.S.; Gasbjerg, L.S. GIP-derived GIP receptor antagonists—A review of their role in GIP receptor pharmacology. Peptides 2024, 177, 171212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, M.; Sachs, S.; Habegger, K.M.; Hofmann, S.M.; Müller, T.D. Glucagon regulation of energy expenditure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, C.; Cota, D.; Quarta, C. Poly-Agonist Pharmacotherapies for Metabolic Diseases: Hopes and New Challenges. Drugs 2023, 84, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enebo, L.B.; Berthelsen, K.K.; Kankam, M.; Lund, M.T.; Rubino, D.M.; Satylganova, A.; Lau, D.C.W. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2·4 mg for weight management: A randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1736–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.M.M.; Minnion, J.; Khoo, B.; Ball, L.J.; Malviya, R.; Day, E.; Fiorentino, F.; Brindley, C.; Bush, J.; Bloom, S.R. Safety and efficacy of an extended-release peptide YY analogue for obesity: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svane, M.S.; Jørgensen, N.B.; Bojsen-Møller, K.N.; Dirksen, C.; Nielsen, S.; Kristiansen, V.B.; Toräng, S.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Hartmann, B.; et al. Peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1 contribute to decreased food intake after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo Nordisk A/S. Financial Report for the Period 1 January 2023 to June 2023. 2023. Available online: https://ml-eu.globenewswire.com/Resource/Download/b4ae7c0b-df06-49cd-a1b9-50d5d566e6bc (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Kanbay, M.; Siriopol, D.; Copur, S.; Hasbal, N.B.; Güldan, M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Garfias-Veitl, T.; von Haehling, S. Effect of Bimagrumab on body composition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B.; Murray, B.; Gutzwiller, S.; Marcaletti, S.; Marcellin, D.; Bergling, S.; Brachat, S.; Persohn, E.; Pierrel, E.; Bombard, F.; et al. Blockade of the Activin Receptor IIB Activates Functional Brown Adipogenesis and Thermogenesis by Inducing Mitochondrial Oxidative Metabolism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2871–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Coleman, L.A.; Miller, R.; Rooks, D.S.; Laurent, D.; Petricoul, O.; Praestgaard, J.; Swan, T.; Wade, T.; Perry, R.G.; et al. Effect of Bimagrumab vs Placebo on Body Fat Mass among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2033457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Kang, C. Mechanisms of action for small molecules revealed by structural biology in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, P. Industry Update: The latest Developments in the Field of Therapeutic Delivery, July 2024. Ther. Deliv. 2024, 15, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genentech: Press Releases. Genentech Announces Positive Phase I Results of Its Oral GLP-1 Receptor Agonist CT-996 for the Treatment of People with Obesity. 2024. Available online: https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/15032/2024-07-16/genentech-announces-positive-phase-i-res (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Carmot Therapeutics Inc. Carmot Therapeutics Announces Completion of Acquisition by Roche. 2024. Available online: https://carmot.us/carmot-therapeutics-announces-completion-of-acquisition-by-roche/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, F.S.; Douros, J.D.; Gabe, M.B.N.; Showalter, A.D.; Wainscott, D.B.; Suter, T.M.; Capozzi, M.E.; van der Velden, W.J.C.; Stutsman, C.; Cardona, G.R.; et al. Tirzepatide is an imbalanced and biased dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willmar, P.; Amanda, T.; Sanjana, J.; James, D.R.; Issa, N.T. A Review of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 in Dermatology. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pechenov, S.; Revell, J.; Will, S.; Naylor, J.; Tyagi, P.; Patel, C.; Liang, L.; Tseng, L.; Huang, Y.; Rosenbaum, A.I.; et al. Development of an orally delivered GLP-1 receptor agonist through peptide engineering and drug delivery to treat chronic disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Shi, J. Advance in peptide-based drug development: Delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayden, D.J.; Hill, T.A.; Fairlie, D.P.; Maher, S.; Mrsny, R.J. Systemic delivery of peptides by the oral route: Formulation and medicinal chemistry approaches. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 157, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiger, M.B.; Steinauer, A.; Gao, D.; Cerrejon, D.K.; Krupke, H.; Heussi, M.; Merkl, P.; Klipp, A.; Burger, M.; Martin-Olmos, C.; et al. Enzymatic absorption promoters for non-invasive peptide delivery. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lexaria Bioscience Corp. Lexaria’s DehydraTECH Technology Has the Potential to Unlock Accelerated Revenue Growth in the GLP-1-Industry. Available online: https://lexariabioscience.com/2025/07/23/lexarias-dehydratech-technology-has-the-potential-to-unlock-accelerated-revenue-growth-in-the-glp-1-industry (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lexaria Bioscience Corp. ALL Study Groups Using DehydraTECH Processing Outperform Rybelsus® in Body Weight Control in Lexaria’s 12-Week GLP-1, Diabetes Animal Study. Available online: https://lexariabioscience.com/2024/11/20/all-study-groups-using-dehydratech-processing-outperform-rybelsus-in-body-weight-control-in-lexarias-12-week-glp-1-diabetes-animal-study (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lexaria Bioscience Corp. Lexaria’s DehydraTECH-Liraglutide Human GLP-1 Clinical Study Supports Pathway to Potential FDA Registration as an Orally-Delivered Capsule. Available online: https://lexariabioscience.com/2025/06/11/lexarias-dehydratech-liraglutide-human-glp-1-clinical-study-supports-pathway-to-potential-fda-registration-as-an-orally-delivered-capsule (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lexaria Bioscience Corp. Lexaria’s Technology Supports Higher Levels of the GLP-1 Drug Semaglutide in Brain. Available online: https://lexariabioscience.com/2025/09/19/lexarias-technology-supports-higher-levels-of-the-glp-1-drug-semaglutide-in-brain (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Ke, Z.; Ma, Q.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Su, Z. Peptide GLP-1 receptor agonists: From injection to oral delivery strategies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 229, 116471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Park, E.J.; Na, D.H. Gastrointestinal Permeation Enhancers for the Development of Oral Peptide Pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Gan, Y.; Yu, M. Oral peptide therapeutics for diabetes treatment: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 2006–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohley, M.; Leroux, J.C. Gastrointestinal Permeation Enhancers Beyond Sodium Caprate and SNAC—What is Coming Next? Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2400843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; La Zara, D.; Blaabjerg, L.; Pessi, J.; Raptis, K.; Toftlev, A.; Sauter, M.; Christophersen, P.; Bardonnet, P.-L.; Andersson, V.; et al. Combining SNAC and C10 in oral tablet formulations for gastric peptide delivery: A preclinical and clinical study. J. Control. Release 2025, 378, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendicho-Lavilla, C.; Seoane-Viaño, I.; Otero-Espinar, F.J.; Luzardo-Álvarez, A. Fighting type 2 diabetes: Formulation strategies for peptide-based therapeutics. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emisphere Technologies INC. Emisphere Reports: First Quarter 2015—Financial Results. 2015. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/805326/000119312515190200/d925281dex991.htm (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Novo Nordisk. Press Release: Novo Nordisk to Acquire Emisphere Technologies and Obtain Ownership of the Eligen® SNAC Oral Delivery Technology. 2020. Available online: https://www.novonordisk.com/news-and-media/news-and-ir-materials/news-details.html?id=33374 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Twarog, C.; Fattah, S.; Heade, J.; Maher, S.; Fattal, E.; Brayden, D.J. Intestinal permeation enhancers for oral delivery of macromolecules: A comparison between salcaprozate sodium (SNAC) and sodium caprate (c10). Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.L.; McEntee, N.; Holland, J.; Patel, A. Development and approval of rybelsus (oral semaglutide): Ushering in a new era in peptide delivery. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wainer, J.; Ryoo, S.W.; Qi, X.; Chang, R.; Li, J.; Lee, S.H.; Min, S.; Wentworth, A.; Collins, J.E.; et al. Dynamic omnidirectional adhesive microneedle system for oral macromolecular drug delivery. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, S.T.; Baekdal, T.A.; Vegge, A.; Maarbjerg, S.J.; Pyke, C.; Ahnfelt-Rønne, J.; Madsen, K.G.; Schéele, S.G.; Alanentalo, T.; Kirk, R.K.; et al. Transcellular stomach absorption of a derivatized glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaar7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanou, M.; Verhoef, J.C.; Junginger, H.E. Chitosan and its derivatives as intestinal absorption enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 50 (Suppl. 1), S91–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Al-Salami, H.; Dass, C.R. The role of chitosan on oral delivery of peptide-loaded nanoparticle formulation. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego, C.; Torres, D.; Alonso, M.J. The potential of chitosan for the oral administration of peptides. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2005, 2, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; et al. How Nanoparticles Open the Paracellular Route of Biological Barriers: Mechanisms, Applications, and Prospects. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 15627–15652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.W.; Lee, P.L.; Chen, C.T.; Mi, F.L.; Juang, J.H.; Hwang, S.M.; Ho, Y.C.; Sung, H.W. Elucidating the signaling mechanism of an epithelial tight-junction opening induced by chitosan. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6254–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Araújo, F.; Mäkilä, E.; Raula, J.; Kauppinen, E.I.; Salonen, J.; Sarmento, B.; Hirvonen, J.; Santos, H.A. Multistage pH-responsive mucoadhesive nanocarriers prepared by aerosol flow reactor technology: A controlled dual protein-drug delivery system. Biomaterials 2015, 68, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, M.; Alameh, M.G.; Buschmann, M.; Merzouki, A. Effective and Safe Gene-Based Delivery of GLP-1 Using Chitosan/Plasmid-DNA Therapeutic Nanocomplexes in an Animal Model of Type 2 Diabetes. Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebarth, J.; da Silva, L.M.; Lorenzett, A.K.P.; Figueiredo, I.D.; Carlstrom, P.F.; Cardoso, F.N.; de Freitas, A.L.F.; Baviera, A.M.; Mainardes, R.M. Oral Delivery of Liraglutide-Loaded Zein/Eudragit-Chitosan Nanoparticles Provides Pharmacokinetic and Glycemic Outcomes Comparable to Its Subcutaneous Injection in Rats. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, D.; Takakusa, H.; Nakai, D. Oral Absorption of Middle-to-Large Molecules and Its Improvement, with a Focus on New Modality Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, M.; Sabri, A.H.; Anjani, Q.K.; Mustaffa, M.F.; Hamid, K.A. Intestinal Absorption Study: Challenges and Absorption Enhancement Strategies in Improving Oral Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Patel, P.J.; Aburub, A.; Sperry, A.; Estwick, S.; ElSayed, M.E.H.; Datta–Mannan, A. Identification of a Multi-Component Formulation for Intestinal Delivery of a GLP-1/Glucagon Co-agonist Peptide. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 2555–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Aihara, E.; Mohammed, F.A.; Qu, H.; Riley, A.; Su, Y. In Vivo Mechanism of Action of Sodium Caprate for Improving the Intestinal Absorption of a GLP1/GIP Coagonist Peptide. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Dogra, M.; Huang, S.; Aihara, E.; ElSayed, M.; Aburub, A. Development and evaluation of C10 and SNAC erodible tablets for gastric delivery of a GIP/GLP1 peptide in monkeys. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 650, 123680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.; Martin, J.; Dogra, M.; Walker, J.; Risley, D.; Aburub, A. Controlling Gastric Delivery of a GIP/GLP1 Peptide in Monkeys by Mucoadhesive SNAC Tablets. Pharm. Res. 2025, 42, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Baker, G.A.; Zhao, H. Ether- and alcohol-functionalized task-specific ionic liquids: Attractive properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4030–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pang, G.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, D. A red light-controlled probiotic bio-system for in-situ gut-brain axis regulation. Biomaterials 2023, 294, 122005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawiyah, N.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Hawatulaila, S.; Goto, M. Ionic liquids as a potential tool for drug delivery systems. Med. Chem. Commun. 2016, 7, 1881–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, E.; Kumar, R.; An, J.M.; Mendoza, H.; Sutradhar, S.C.; Choi, W.; Narayan, M.; Lee, Y.-K.; Nurunnabi, M. Potentials of ionic liquids to overcome physical and biological barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 204, 115157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Sun, Y.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y. Ionic Liquids: Promising Approach for Oral Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 2353–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S. Choline geranate (CAGE): A multifaceted ionic liquid for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2024, 376, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Ibsen, K.; Brown, T.; Chen, R.; Agatemor, C.; Mitragotri, S. Ionic liquids for oral insulin delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 7296–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agatemor, C.; Brown, T.D.; Gao, Y.; Ohmori, N.; Ibsen, K.N.; Mitragotri, S. Choline-Geranate Deep Eutectic Solvent Improves Stability and Half-Life of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1. Adv. Ther. 2021, 4, 2000180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahkam, M.; Hosseinzadeh, F.; Galehassadi, M. Preparation of Ionic Liquid Functionalized Silica Nanoparticles for Oral Drug Delivery. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol 2012, 3, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Ibsen, K.N.; Tanner, E.E.L.; Mitragotri, S. Oral ionic liquid for the treatment of diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 25042–25047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebollo, R.; Niu, Z.; Blaabjerg, L.; La Zara, D.; Juel, T.; Pedersen, H.D.; Andersson, V.; Benova, M.; Krogh, C.; Pons, R.; et al. Salcaprozate-based ionic liquids for GLP-1 gastric delivery: A mechanistic understanding of in vivo performance. J. Control. Release 2025, 377, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudry-Kochavi, L.; Naraykin, N.; Di Paola, R.; Gugliandolo, E.; Peritore, A.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Ziv, E.; Nassar, T.; Benita, S. Pharmacodynamical effects of orally administered exenatide nanoparticles embedded in gastro-resistant microparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 133, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedulin, B.R.; Smith, P.A.; Jodka, C.M.; Chen, K.; Bhavsar, S.; Nielsen, L.L.; Parkes, D.G.; Young, A.A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide following alternate routes of administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 356, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kweon, S.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.K.; Kang, S.H.; Chang, K.Y.; Choi, J.U.; Park, J.; Shim, J.-H.; Park, J.W.; Byun, Y. Coordinated ASBT and EGFR Mechanisms for Optimized Liraglutide Nanoformulation Absorption in the GI Tract. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 2973–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Wey, S.P.; Juang, J.H.; Sonaje, K.; Ho, Y.C.; Chuang, E.Y.; Hsu, C.-W.; Yen, T.-C.; Lin, K.-J.; Sung, H.-W. The glucose-lowering potential of exendin-4 orally delivered via a pH-sensitive nanoparticle vehicle and effects on subsequent insulin secretion in vivo. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudry-Kochavi, L.; Naraykin, N.; Nassar, T.; Benita, S. Improved oral absorption of exenatide using an original nanoencapsulation and microencapsulation approach. J. Control. Release 2015, 217, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Lee, I.H.; Lee, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.C.; Jon, S. Oral delivery of an anti-diabetic peptide drug via conjugation and complexation with low molecular weight chitosan. J. Control. Release 2013, 170, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, F.; Shrestha, N.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Fonte, P.; Mäkilä, E.M.; Salonen, J.J.; Hirvonen, J.T.; Granja, P.L.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B. The impact of nanoparticles on the mucosal translocation and transport of GLP-1 across the intestinal epithelium. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9199–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Trevaskis, N.L. Impact of nanoparticle properties on immune cell interactions in the lymph node. Acta Biomater. 2025, 193, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.F.T.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B.F.C.C. New insights into nanomedicines for oral delivery of glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 16, e1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pridgen, E.M.; Alexis, F.; Kuo, T.T.; Levy-Nissenbaum, E.; Karnik, R.; Blumberg, R.S.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C. Transepithelial transport of Fc-targeted nanoparticles by the neonatal Fc receptor for oral delivery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 213ra167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomme Peter, T.; MCCann Karl, B. Transferrin: Structure, function and potential therapeutic actions. Drug. Discov. Today 2005, 10, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Diao, H.; Feng, Z.C.; Lau, A.; Wang, R.; Jevnikar, A.M.; Ma, S. A fusion protein derived from plants holds promising potential as a new oral therapy for type 2 diabetes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Woo, J.H.; Kim, M.K.; Woo, S.S.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, H.G.; Lee, N.K.; Choi, Y.J. Identification of a peptide sequence that improves transport of macromolecules across the intestinal mucosal barrier targeting goblet cells. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 135, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, C.; Yin, M.; Chu, L.; Yan, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. Synthesis of CSK-DEX-PLGA Nanoparticles for the Oral Delivery of Exenatide to Improve Its Mucus Penetration and Intestinal Absorption. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y. Goblet cell-targeting nanoparticles for oral insulin delivery and the influence of mucus on insulin transport. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, L.; Lin, M.; Bao, X.; Zhong, H.; Ke, P.; Dai, Q.; Yang, Q.; Tang, X.; Xu, W.; et al. Double layer spherical nanoparticles with hyaluronic acid coating to enhance oral delivery of exenatide in T2DM rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 191, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, M.A.; Clémençon, B.; Burrier, R.E.; Bruford, E.A. The ABCs of membrane transporters in health and disease (SLC series): Introduction. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ding, R.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, A.; Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Folic acid-modified reverse micelle-lipid nanocapsules overcome intestinal barriers and improve the oral delivery of peptides. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2181744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, A.; Qiu, Y.; Fan, W.; Hovgaard, L.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. The upregulated intestinal folate transporters direct the uptake of ligand-modified nanoparticles for enhanced oral insulin delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1460–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.C.; Jin, C.H.; Han, J.S.; Yu, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Kang, C.L. Preparation, characterization, and application of biotinylated and biotin-PEGylated glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues for enhanced oral delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2008, 19, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, Y.S.; Chae, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Kwon, M.J.; Shin, H.J.; Lee, K.C. Improved peroral delivery of glucagon-like peptide-1 by site-specific biotin modification: Design, preparation, and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 68, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.W.; Kalitsky, J.; St-Pierre, S.; Brubaker, P.L. Oral delivery of glucagon-like peptide-1 in a modified polymer preparation normalizes basal glycaemia in diabetic db/db mice. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; He, D.; Fan, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y. Oral Delivery of Exenatide via Microspheres Prepared by Cross-Linking of Alginate and Hyaluronate. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Zheng, X.; Bai, R.; Yang, Y.; Jian, L. Utilization of PLGA nanoparticles in yeast cell wall particle system for oral targeted delivery of exenatide to improve its hypoglycemic efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Gu, T.; Dong, Q.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Kong, W. Preparation, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo investigation of chitosan-coated poly (d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for intestinal delivery of exendin-4. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.; Shrestha, N.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Liu, D.; Herranz-Blanco, B.; Mäkilä, E.M.; Salonen, J.J.; Hirvonen, J.T.; Granja, P.L.; Sarmento, B.; et al. Microfluidic Assembly of a Multifunctional Tailorable Composite System Designed for Site Specific Combined Oral Delivery of Peptide Drugs. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 8291–8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.; Shrestha, N.; Gomes, M.J.; Herranz-Blanco, B.; Liu, D.; Hirvonen, J.J.; Granja, P.L.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B. In vivo dual-delivery of glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitor through composites prepared by microfluidics for diabetes therapy. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 10706–10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, K.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Fc-modified exenatide-loaded nanoparticles for oral delivery to improve hypoglycemic effects in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Song, Y.; Duan, D.; Zhang, X.; Sun, K.; Li, Y. Tf ligand-receptor-mediated exenatide-Zn2+ complex oral-delivery system for penetration enhancement of exenatide. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, C.; Yin, M.; Zhang, X.; Sun, K. Oral delivery system for low molecular weight protamine-dextran-poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) carrying exenatide to overcome the mucus barrier and improve intestinal targeting efficiency. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, R.; Bocsik, A.; Katona, G.; Gróf, I.; Deli, M.A.; Csóka, I. Encapsulation in polymeric nanoparticles enhances the enzymatic stability and the permeability of the glp-1 analog, liraglutide, across a culture model of intestinal permeability. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Sovány, T.; Gácsi, A.; Ambrus, R.; Katona, G.; Imre, N.; Csóka, I. Synthesis and Statistical Optimization of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles Encapsulating GLP1 Analog Designed for Oral Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senduran, N.; Yadav, H.N.; Vishwakarma, V.K.; Bhatnagar, P.; Gupta, P.; Bhatia, J.; Dinda, A.K. Orally deliverable nanoformulation of liraglutide against type 2 diabetic rat model. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wu, Z.; Xing, L.; Liu, X.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, Y. Mimicking natural cholesterol assimilation to elevate the oral delivery of liraglutide for type II diabetes therapy. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ding, R.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A.; Sun, K.; et al. Orally administered intelligent self-ablating nanoparticles: A new approach to improve drug cellular uptake and intestinal absorption. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Hosseini, M.; Buckley, S.T.; Yin, W.; Garousi, J.; Gräslund, T.; van Ijzendoorn, S.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B. Nanoparticles targeting the intestinal Fc receptor enhance intestinal cellular trafficking of semaglutide. J. Control. Release 2024, 366, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Viegas, J.; Cristelo, C.; Pacheco, C.; Barros, S.; Buckley, S.T.; Garousi, J.; Gräslund, T.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B. Bioengineered Nanomedicines Targeting the Intestinal Fc Receptor Achieve the Improved Glucoregulatory Effect of Semaglutide in a Type 2 Diabetic Mice Model. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 28406–28424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ding, R.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, T.; Zheng, W.; Chen, E.; Wang, A.; Shi, Y. Sulfobetaine modification of poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles enhances mucus permeability and improves bioavailability of orally delivered liraglutide. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 93, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, P.; Grundmann, C.; Sauter, M.; Storck, P.; Tursch, A.; Özbek, S.; Leotta, K.; Roth, R.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; et al. Coating of PLA-Nanoparticles with Cyclic, Arginine-Rich Cell Penetrating Peptides Enables Oral Delivery of Liraglutide. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2020, 24, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Liang, R.; Sun, F.; Shi, Y.; Wang, A.; Liu, W.; Sun, K.; Li, Y. The Glucose-Lowering Potential of Exenatide Delivered Orally via Goblet Cell- Targeting Nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Song, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, K.; Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Intelligent Escape System for the Oral Delivery of Liraglutide: A Perfect Match for Gastrointestinal Barriers. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yin, M.; Song, Y.; Wang, T.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, K.; Li, Y. Oral delivery of liraglutide-loaded Poly-N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide/chitosan nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and pharmacokinetics. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 35, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, D.K.; Vishwakarma, V.K.; Singh, R.; Jadhav, K.; Shah, S.; Arora, T.; Verma, R.K.; Yadav, H.N. Fat fighting liraglutide based nano-formulation to reverse obesity: Design, development and animal trials. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 634, 122585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Li, Y.; Hovgaard, L.; Li, S.; Dai, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. A silica-based pH-sensitive nanomatrix system improves the oral absorption and efficacy of incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-l. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 4983–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Araújo, F.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Mäkilä, E.; Gomes, M.J.; Airavaara, M.; Kauppinen, E.I.; Raula, J.; Salonen, J.; Hirvonen, J.; et al. Oral hypoglycaemic effect of GLP-1 and DPP4 inhibitor based nanocomposites in a diabetic animal model. J. Control. Release 2016, 232, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.P.; Liu, D.; Fontana, F.; Ferreira, M.P.A.; Correia, A.; Valentino, S.; Kemell, M.; Moslova, K.; Mäkilä, E.; Salonen, J.; et al. Microfluidic Nanoassembly of Bioengineered Chitosan-Modified FcRn-Targeted Porous Silicon Nanoparticles @ Hypromellose Acetate Succinate for Oral Delivery of Antidiabetic Peptides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 44354–44367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeer, M.M.; Meka, A.K.; Pujara, N.; Kumeria, T.; Strounina, E.; Nunes, R.; Costa, A.; Sarmento, B.; Hasnain, S.Z.; Ross, B.P.; et al. Rationally designed dendritic silica nanoparticles for oral delivery of exenatide. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.; Bouttefeux, O.; Vanvarenberg, K.; Lundquist, P.; Cunarro, J.; Tovar, S.; Khodus, G.; Andersson, E.; Keita, Å.V.; Gonzalez Dieguez, C.; et al. The stimulation of GLP-1 secretion and delivery of GLP-1 agonists: Via nanostructured lipid carriers. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Van Hul, M.; Suriano, F.; Préat, V.; Cani, P.D.; Beloqui, A. Novel strategy for oral peptide delivery in incretin-based diabetes treatment. Gut 2020, 69, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; De Keersmaecker, H.; Braeckmans, K.; De Smedt, S.; Cani, P.D.; Préat, V.; Beloqui, A. Targeted nanoparticles towards increased L cell stimulation as a strategy to improve oral peptide delivery in incretin-based diabetes treatment. Biomaterials 2020, 255, 120209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, I.; Yagoubi, H.; Zhang, W.; Marotti, V.; Kambale, E.K.; Vints, K.; Sliwinska, M.A.; Leclercq, I.A.; Beloqui, A. Effects of semaglutide-loaded lipid nanocapsules on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 2917–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kim, K.S.; Bae, Y.H. Long-Term Oral Administration of Exendin-4 to Control Type 2 Diabetes in a Rat Model. J. Control. Release 2019, 294, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zhao, Z.; He, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, R.; Sun, K.; Shi, Y. Preparation, Drug Distribution, and In Vivo Evaluation of the Safety of Protein Corona Liposomes for Liraglutide Delivery. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, R.; Wang, A.; Sun, K.; Wang, H.; et al. Design of Auto-Adaptive Drug Delivery System for Effective Delivery of Peptide Drugs to Overcoming Mucus and Epithelial Barriers. AAPS J. 2024, 26, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Holzeisen, T.; Laffleur, F.; Zaichik, S.; Abdulkarim, M.; Gumbleton, M.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. In vivo evaluation of an oral self-emulsifying drug delivery system (SEDDS) for exenatide. J. Control. Release 2018, 277, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.Q.; Ismail, R.; Le-Vinh, B.; Zaichik, S.; Laffleur, F.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. The Effect of Counterions in Hydrophobic Ion Pairs on Oral Bioavailability of Exenatide. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5032–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Phan, T.N.Q.; Laffleur, F.; Csóka, I.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Hydrophobic ion pairing of a GLP-1 analogue for incorporating into lipid nanocarriers designed for oral delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 152, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.Y.; Chen, K.H.; Miao, Y.B.; Chen, H.L.; Lin, K.J.; Chen, C.T.; Yeh, C.-N.; Chang, Y.; Sung, H.-W. Phase-Changeable Nanoemulsions for Oral Delivery of a Therapeutic Peptide: Toward Targeting the Pancreas for Antidiabetic Treatments Using Lymphatic Transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1809015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Xin, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jin, M.; Gao, Z.; Huang, W. Effective oral delivery of Exenatide-Zn2+ complex through distal ileum-targeted double layers nanocarriers modified with deoxycholic acid and glycocholic acid in diabetes therapy. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 120944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presas, E.; Tovar, S.; Cuñarro, J.; O’Shea, J.P.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Pre-Clinical Evaluation of a Modified Cyclodextrin-Based Nanoparticle for Intestinal Delivery of Liraglutide. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, D.; Li, D.; He, C.; Chen, X. A pH-Triggered Self-Unpacking Capsule Containing Zwitterionic Hydrogel-Coated MOF Nanoparticles for Efficient Oral Exendin-4 Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Qian, K.; Yao, P. Oral delivery of exenatide-loaded hybrid zein nanoparticles for stable blood glucose control and β-cell repair of type 2 diabetes mice. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Qian, K.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Pan, T.; Wang, Z.; Yao, P.; Lin, L. Intestinal epithelium penetration of liraglutide via cholic acid pre-complexation and zein/rhamnolipids nanocomposite delivery. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Guo, C.; Feng, Y.; Qi, P.; Yin, T.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; et al. Milk Exosome-Liposome Hybrid Vesicles with Self-Adapting Surface Properties Overcome the Sequential Absorption Barriers for Oral Delivery of Peptides. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 21091–21111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.G.; Kim, D.H.; Han, H.K. Fabrication and Evaluation of a pH-Responsive Nanocomposite-Based Colonic Delivery System for Improving the Oral Efficacy of Liraglutide. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 3937–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.L.; Song, J.G.; Han, H.K. Enhanced Oral Efficacy of Semaglutide via an Ionic Nanocomplex with Organometallic Phyllosilicate in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, L.; Bamjan, A.D.; Phuyal, S.; Shim, J.H.; Cho, S.S.; Seo, J.B.; Chang, K.-Y.; Byun, Y.; Kweon, S.; Park, J.W. An oral liraglutide nanomicelle formulation conferring reduced insulin-resistance and long-term hypoglycemic and lipid metabolic benefits. J. Control. Release 2025, 378, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamson, N.G.; Berger, A.; Fein, K.C.; Whitehead, K.A. Anionic Nanoparticles Enable the Oral Delivery of Proteins by Enhancing Intestinal Permeability. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]