Compound KTI-2338 Inhibits ACVR1 Receptor Signaling in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatments

2.3. Western Blot

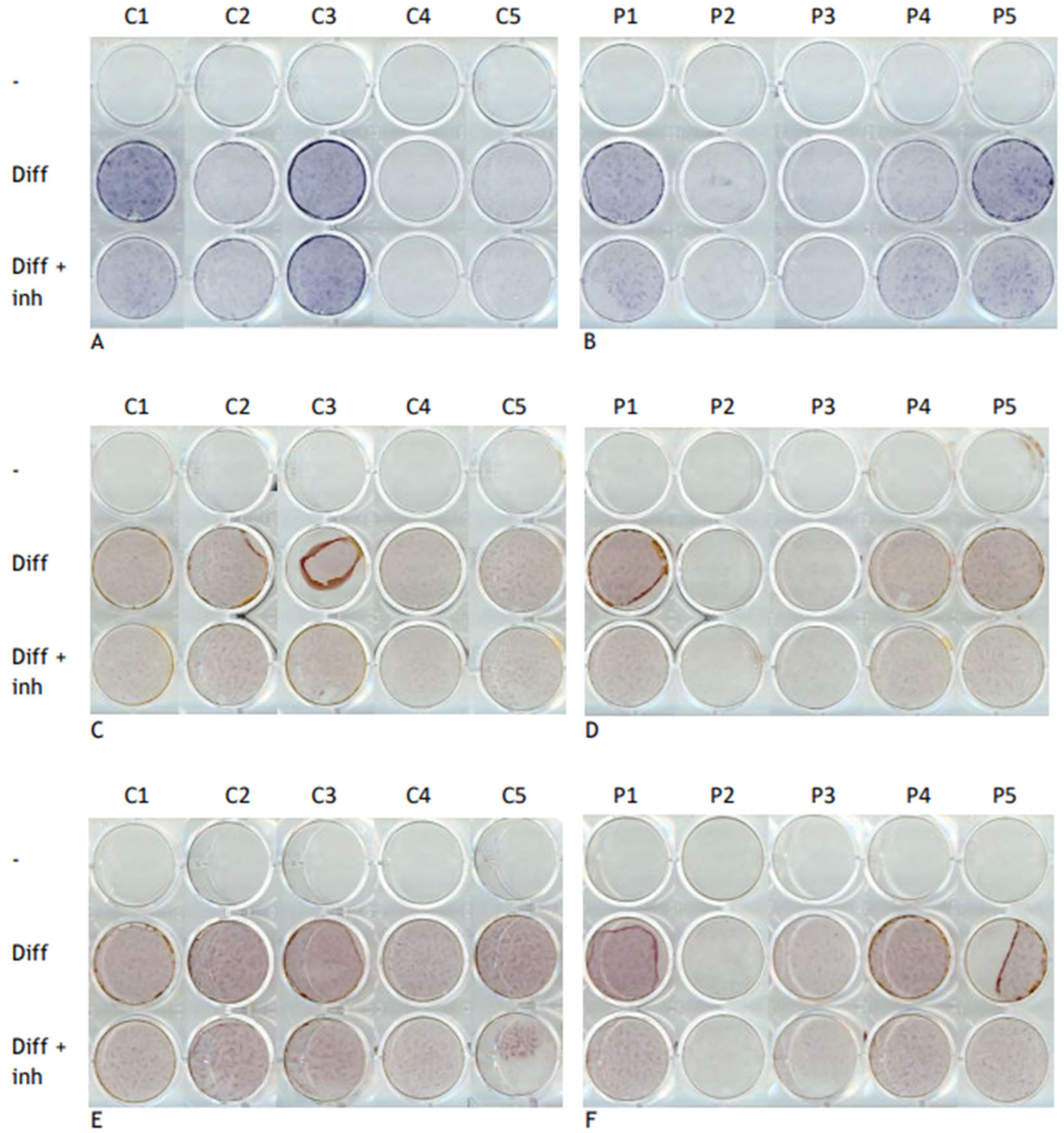

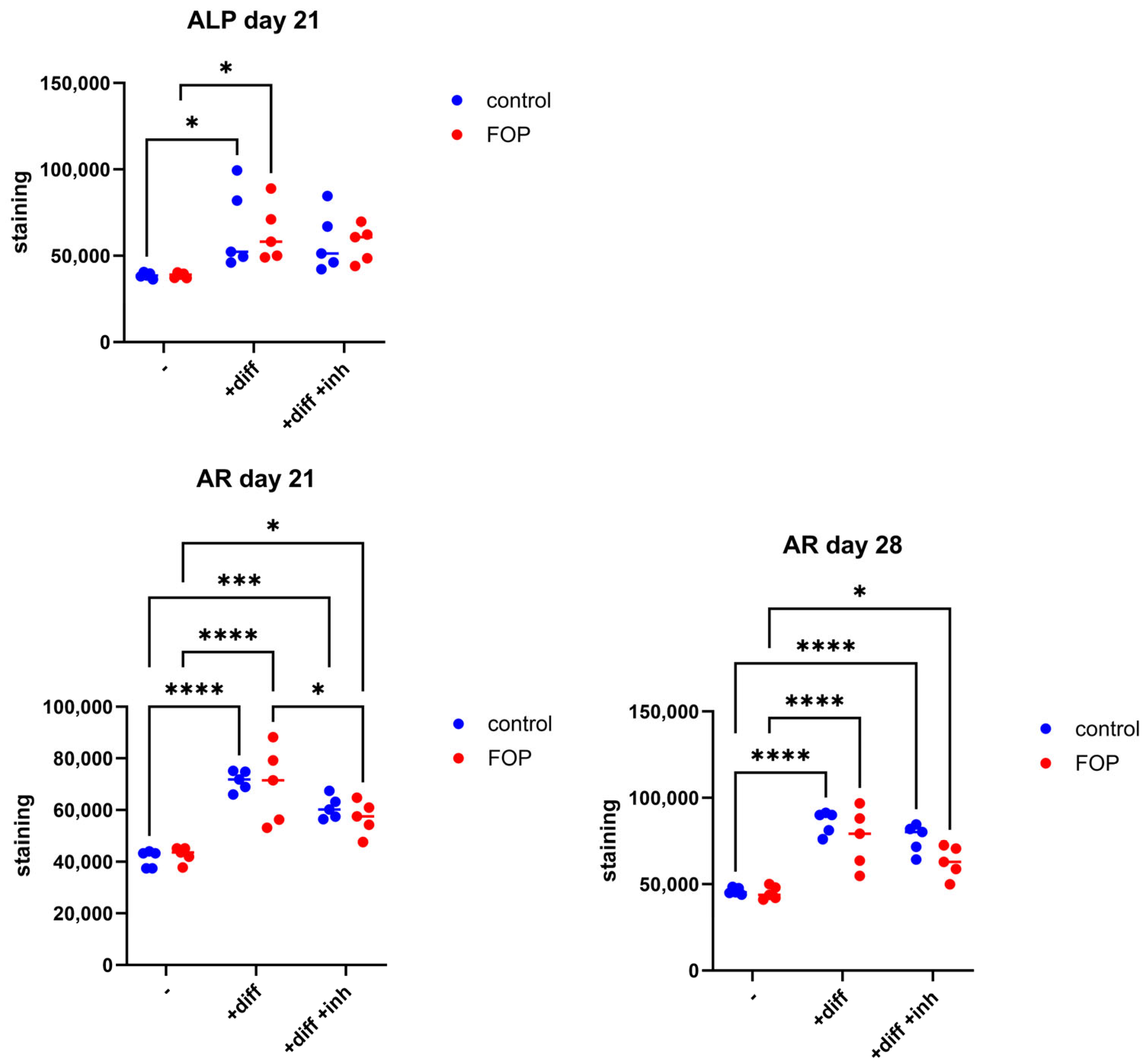

2.4. Osteogenic Transdifferentiation

2.5. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

2.6. Alkaline Phosphatase and Alizarin Red Staining

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Inhibitor KTI-2338 Decreases Activin A-Stimulated pSMAD1/5/9 Signaling in FOP Fibroblasts

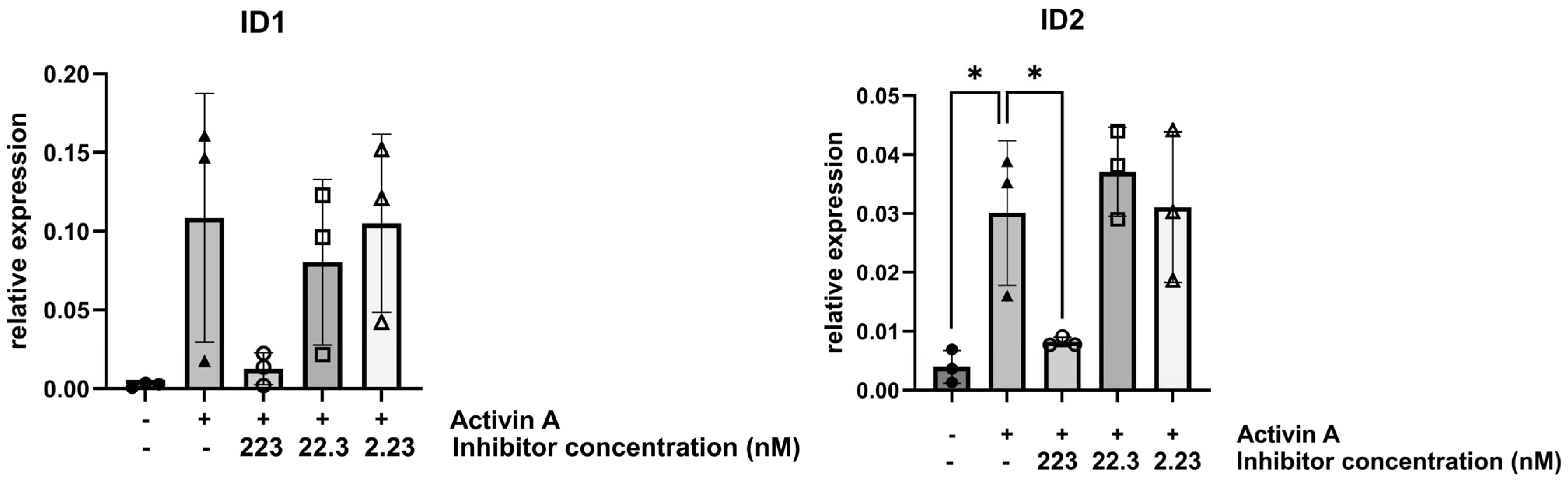

3.2. Inhibitor KTI-2338 Decreases Activin A-Stimulated Expression of TGFβ Superfamily-Regulated Genes in FOP Fibroblasts

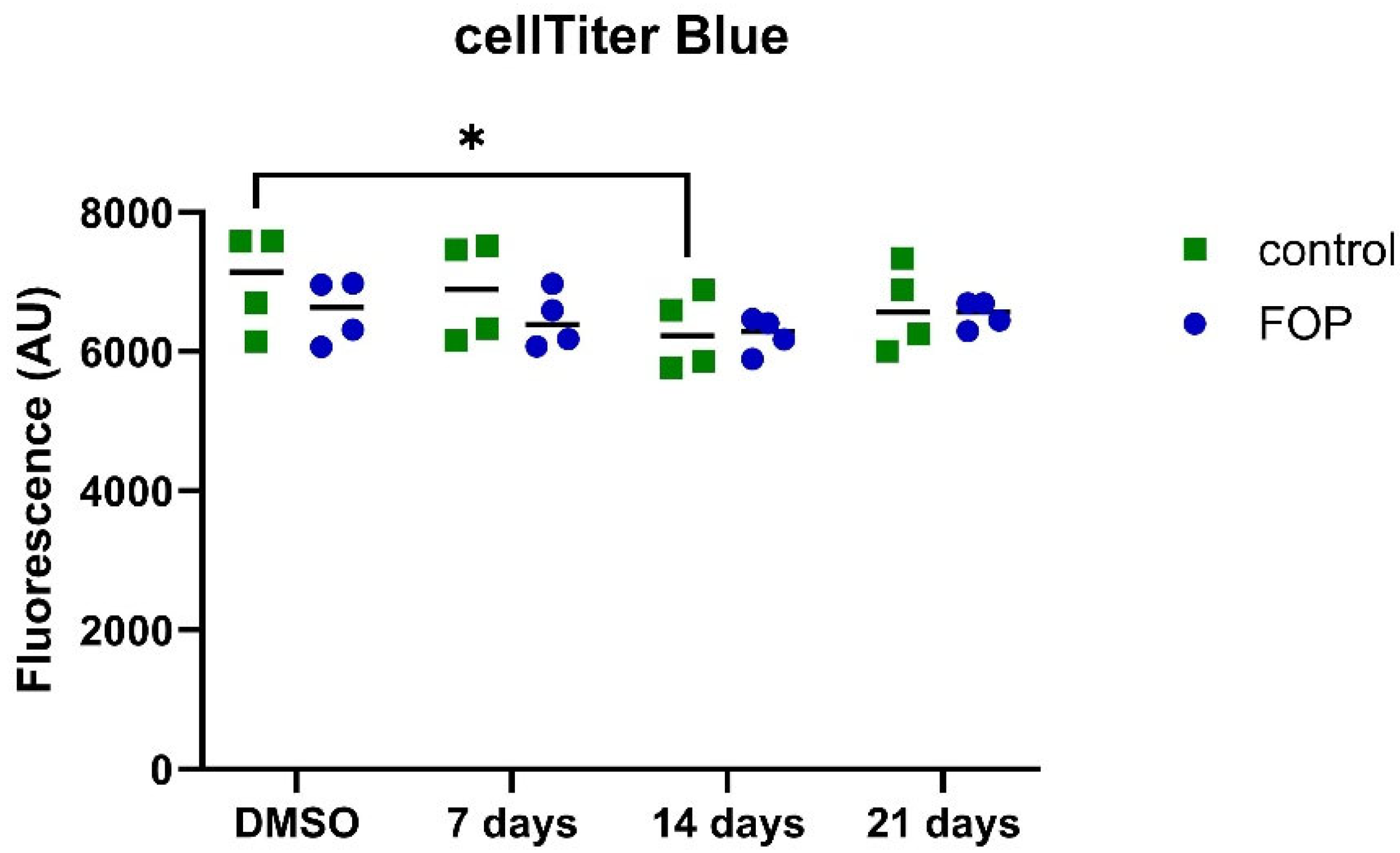

3.3. Cell Viability Is Unaffected by the Inhibitor

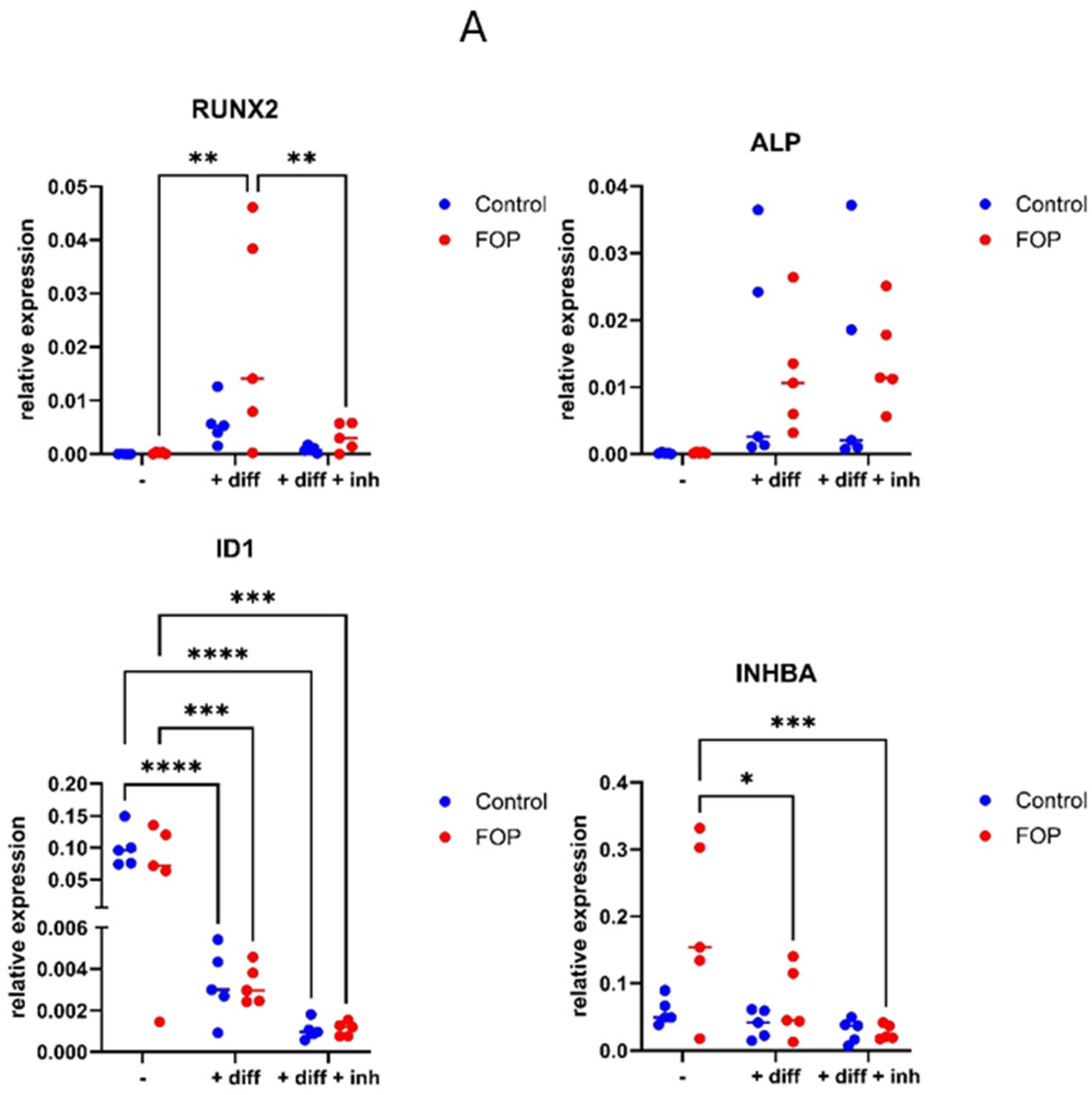

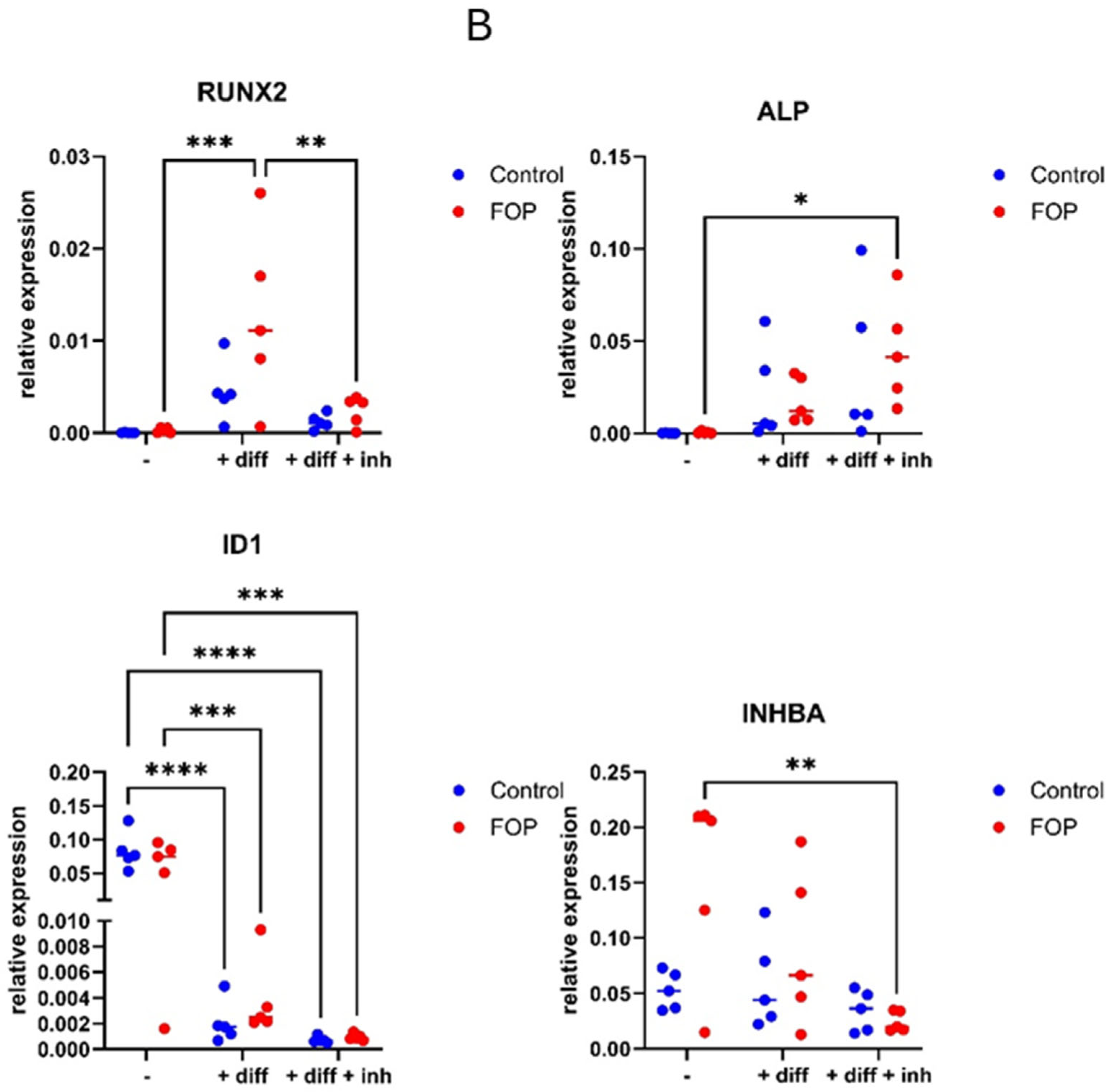

3.4. Expression of Osteogenic Differentiation Genes RUNX2, ID1, and INHBA Decreased in FOP Cells After Inhibitor Treatment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baujat, G.; Choquet, R.; Bouée, S.; Jeanbat, V.; Courouve, L.; Ruel, A.; Michot, C.; Sang, K.-H.L.Q.; Lapidus, D.; Messiaen, C.; et al. Prevalence of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) in France: An estimate based on a record linkage of two national databases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignolo, R.J.; Hsiao, E.C.; Baujat, G.; Lapidus, D.; Sherman, A.; Kaplan, F.S. Prevalence of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) in the United States: Estimate from three treatment centers and a patient organization. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, Y.; Haga, N.; Kitoh, H.; Kamizono, J.; Tozawa, K.; Katagiri, T.; Susami, T.; Fukushi, J.; Iwamoto, Y. Deformity of the great toe in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J. Orthop. Sci. 2010, 15, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.W.; Zasloff, M., Jr. The hand and foot malformations in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Johns Hopkins Med. J. 1980, 147, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pignolo, R.J.; Baujat, G.; Brown, M.A.; De Cunto, C.; Hsiao, E.C.; Keen, R.; Al Mukaddam, M.; Sang, K.-H.L.Q.; Wilson, A.; Marino, R.; et al. The natural history of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: A prospective, global 36-month study. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 2422–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignolo, R.J.; Bedford-Gay, C.; Liljesthröm, M.; Durbin-Johnson, B.P.; Shore, E.M.; Rocke, D.M.; Kaplan, F.S. The Natural History of Flare-Ups in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP): A Comprehensive Global Assessment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, F.S.; Zasloff, M.A.; Kitterman, J.A.; Shore, E.M.; Hong, C.C.; Rocke, D.M. Early mortality and cardiorespiratory failure in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2010, 92, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Duffhues, G.; Williams, E.; Goumans, M.J.; Heldin, C.H.; Ten Dijke, P. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors: Structure, function and targeting by selective small molecule kinase inhibitors. Bone 2020, 138, 115472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Shi, F.; Gao, J.; Hua, P. The role of Activin A in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: A prominent mediator. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, E.M.; Xu, M.; Feldman, G.J.; Fenstermacher, D.A.; Cho, T.J.; Choi, I.H.; Connor, J.M.; Delai, P.; Glaser, D.L.; LeMerrer, M.; et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykul, S.; Corpina, R.A.; Goebel, E.J.; Cunanan, C.J.; Dimitriou, A.; Kim, H.J.; Zhang, Q.; Rafique, A.; Leidich, R.; Wang, X.; et al. Activin A forms a non-signaling complex with ACVR1 and type II Activin/BMP receptors via its finger 2 tip loop. Elife 2020, 9, e54582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, F.S.; Fiori, J.; DE LA Peña, L.S.; Ahn, J.; Billings, P.C.; Shore, E.M. Dysregulation of the BMP-4 signaling pathway in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2006, 1068, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Kohda, M.; Kanomata, K.; Nojima, J.; Nakamura, A.; Kamizono, J.; Noguchi, Y.; Iwakiri, K.; Kondo, T.; Kurose, J.; et al. Constitutively activated ALK2 and increased SMAD1/5 cooperatively induce bone morphogenetic protein signaling in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 7149–7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Little, S.C.; Xu, M.; Haupt, J.; Ast, C.; Katagiri, T.; Mundlos, S.; Seemann, P.; Kaplan, F.S.; Mullins, M.C.; et al. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva R206H ACVR1 mutation activates BMP-independent chondrogenesis and zebrafish embryo ventralization. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3462–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheij, V.A.; Diecidue, R.J.; Botman, E.; Harrington, J.D.; Haga, N.; Hidalgo-Bravo, A.; Delai, P.L.R.; Madhuri, V.; Al Mukaddam, M.; Zhang, K.; et al. Palovarotene in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: Review and perspective. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2025, 26, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backus, T.; Medeiros, N.; Materna, C.; Fisher, F.; Lachey, J.; Seehra, J. ALK2 is a potential therapeutic target in anemia resulting from chronic inflammation [poster]. In Proceedings of the European Hematology Association, Virtual, 9–17 June 2021; Available online: https://kerostx.com/scientific-publications/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Backus, T.A.; Medeiros, N.M.; Lema, E.M.; Fisher, F.M.; Seehra, J.S.; Lachey, J.L. Targeted ALK2 Inhibition as a Therapeutic Approach to Reducing Hepcidin and Elevating Serum Iron [poster]. In Proceedings of the European School of Hematology, 2nd Translational Research Conference: Erythropoiesis control and Ineffective Erythropoiesis: From bench to bedside, Virtual, 5–7 March 2021; Available online: https://kerostx.com/scientific-publications/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Jiang, J.K.; Huang, X.; Shamim, K.; Patel, P.R.; Lee, A.; Wang, A.Q.; Nguyen, K.; Tawa, G.; Cuny, G.D.; Yu, P.B.; et al. Discovery of 3-(4-sulfamoylnaphthyl) pyrazolo [1,5-a] pyrimidines as potent and selective ALK2 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 3356–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.B.; Deng, D.Y.; Lai, C.S.; Hong, C.C.; Cuny, G.D.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Hong, D.W.; McManus, P.M.; Katagiri, T.; Sachidanandan, C.; et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic [corrected] ossification. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitterman, J.A.; Kantanie, S.; Rocke, D.M.; Kaplan, F.S. Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnostic errors in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e654–e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micha, D.; Voermans, E.; Eekhoff, M.E.; van Essen, H.W.; Zandieh-Doulabi, B.; Netelenbos, C.; Rustemeyer, T.; Sistermans, E.; Pals, G.; Bravenboer, N. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling decreases osteogenic differentiation of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva fibroblasts in a novel in vitro model of the disease. Bone 2016, 84, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, R.D.; Wisse, L.E.; Schoenmaker, T.; Yaqub, M.; Sánchez-Duffhues, G.; Eekhoff, E.M.W.; Micha, D. TGF-Beta Induces Activin a Production in Dermal Fibroblasts Derived from Patients with Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valer, J.A.; Sánchez-de-Diego, C.; Pimenta-Lopes, C.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. ACVR1 Function in Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, L.; Jones, C. Recent Advances in ALK2 Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 20729–20734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rovira, T.; Chalaux, E.; Massagué, J.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. Direct binding of Smad1 and Smad4 to two distinct motifs mediates bone morphogenetic protein-specific transcriptional activation of Id1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 3176–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchynskyi, O.; ten Dijke, P. Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 4883–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Kang, Q.; Luo, Q.; Jiang, W.; Si, W.; Liu, B.A.; Luu, H.H.; Park, J.K.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; et al. Inhibitor of DNA binding/differentiation helix-loop-helix proteins mediate bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32941–32949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cayami, F.K.; Claeys, L.; de Ruiter, R.; Smilde, B.J.; Wisse, L.; Bogunovic, N.; Riesebos, E.; Eken, L.; Kooi, I.; Sistermans, E.A.; et al. Osteogenic transdifferentiation of primary human fibroblasts to osteoblast-like cells with human platelet lysate. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorakova, J.; Wiesnerova, L.; Chocholata, P.; Kulda, V.; Landsmann, L.; Cedikova, M.; Kripnerova, M.; Eberlova, L.; Babuska, V. Human cells with osteogenic potential in bone tissue research. Biomed. Eng. Online 2023, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denu, R.A.; Nemcek, S.; Bloom, D.D.; Goodrich, A.; Kim, J.; Mosher, D.F.; Hematti, P. Fibroblasts and Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells Are Phenotypically Indistinguishable. Acta Haematol. 2016, 136, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, M.A.; Collin, M.P.; Buckley, C.D.; Dazzi, F. Mesenchymal stem cells: The fibroblasts’ new clothes? Haematologica 2009, 94, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, L.; Bravenboer, N.; Eekhoff, E.M.W.; Micha, D. Human Fibroblasts as a Model for the Study of Bone Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, J.C.; Puzzi, M.B. The effect of aging in primary human dermal fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmaker, T.; Mokry, M.; Micha, D.; Netelenbos, C.; Bravenboer, N.; Gilijamse, M.; Eekhoff, E.M.W.; De Vries, T.J. Activin-A Induces Early Differential Gene Expression Exclusively in Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts from Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Patients. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, J.J.; Bauer, J.; Jana, A.; Tian, J.; Carroll, T.; Mancinelli, G.; Özden, Ö.; Krett, N.; Guzman, G.; Kerr, D.; et al. Activin signaling is an essential component of the TGF-β induced pro-metastatic phenotype in colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Duffhues, G.; Williams, E.; Benderitter, P.; Orlova, V.; van Wijhe, M.; Garcia de Vinuesa, A.; Kerr, G.; Caradec, J.; Lodder, K.; de Boer, H.C.; et al. Development of Macrocycle Kinase Inhibitors for ALK2 Using Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva-Derived Endothelial Cells. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shore, E.M.; Pignolo, R.J.; Kaplan, F.S. Activin A amplifies dysregulated BMP signaling and induces chondro-osseous differentiation of primary connective tissue progenitor cells in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Bone 2018, 109, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Orlova, V.V.; Cai, X.; Eekhoff, E.M.; Zhang, K.; Pei, D.; Pan, G.; Mummery, C.L.; Ten Dijke, P. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Model Human Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 5, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, T.J.; Schoenmaker, T.; Micha, D.; Hogervorst, J.; Bouskla, S.; Forouzanfar, T.; Pals, G.; Netelenbos, C.; Eekhoff, E.M.W.; Bravenboer, N. Periodontal ligament fibroblasts as a cell model to study osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Bone 2018, 109, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Kim, J.M.; Xie, J.; Chaugule, S.; Lin, C.; Ma, H.; Hsiao, E.; Hong, J.; Chun, H.; Shore, E.M.; et al. Suppression of heterotopic ossification in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva using AAV gene delivery. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, S.; Kampfrath, B.; Fischer, K.; Hildebrand, L.; Haupt, J.; Stachelscheid, H.; Knaus, P. ActivinA Induced SMAD1/5 Signaling in an iPSC Derived EC Model of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP) Can Be Rescued by the Drug Candidate Saracatinib. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.J.; Brooijmans, N.; Brubaker, J.D.; Stevison, F.; LaBranche, T.P.; Albayya, F.; Fleming, P.; Hodous, B.L.; Kim, J.L.; Kim, S.; et al. An ALK2 inhibitor, BLU-782, prevents heterotopic ossification in a mouse model of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eabp8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell Line | Diagnosis | Gender | Age at Biopsy | Flare-Up < 1 Week Prior to Biopsy | Medication at Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | FOP | M | 23 | No | No |

| P2 | FOP | F | 21 | Yes | Celecoxib |

| P3 | FOP | M | 62 | No | No |

| P4 | FOP | M | 14 | Yes | Naproxen |

| P5 | FOP | F | 39 | Yes | Tramadol |

| C1 | Control | F | 48 | N/a | Unknown |

| C2 | Control | M | 44 | N/a | Unknown |

| C3 | Control | M | 33 | N/a | Unknown |

| C4 | Control | Unknown | 54 | N/a | Unknown |

| C5 | Control | M | 29 | N/a | Unknown |

| Gene | NM Number | Sequence | Strand | Tm | Product Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP | NM_000478 | AGGGACATTGACGTGATCAT CCTGGCTCGAAGAGACC | F R | 56.62 56.21 | 242 |

| RUNX2 | NM_001024630.4 | ATGCTTCATTCGCCTCAC ACTGCTTGCAGCCTTAAAT | F R | 60.67 60.23 | 105 |

| ID1 | NM_002165 | AATCCGAAGTTGGAACCCCC AACGCATGCCGCCTCG | F R | 59.96 60.91 | 104 |

| ID2 | NM_002166 | GTGGCTGAATAAGCGGTGTTC CTGGTATTCACGCTCCACCT | F R | 59.87 59.46 | 371 |

| INHBA | NM_002192 | GTTTGCCGAGTCAGGAACAG TCACAGGCAATCCGAACGTC | F R | 59.13 60.67 | 360 |

| YWHAZ | NM_001135701.2 | GATGAAGCCATTGCTGAACTTG CTATTTGTGGGACAGCATGGA | F R | 58.49 58.00 | 229 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosenberg, N.M.; Zhytnik, L.; Wisse, L.E.; Botman, E.; Lachey, J.L.; Eekhoff, E.M.W.; Micha, D. Compound KTI-2338 Inhibits ACVR1 Receptor Signaling in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121590

Rosenberg NM, Zhytnik L, Wisse LE, Botman E, Lachey JL, Eekhoff EMW, Micha D. Compound KTI-2338 Inhibits ACVR1 Receptor Signaling in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121590

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosenberg, Neeltje M., Lidiia Zhytnik, Lisanne E. Wisse, Esmée Botman, Jennifer L. Lachey, E. Marelise W. Eekhoff, and Dimitra Micha. 2025. "Compound KTI-2338 Inhibits ACVR1 Receptor Signaling in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121590

APA StyleRosenberg, N. M., Zhytnik, L., Wisse, L. E., Botman, E., Lachey, J. L., Eekhoff, E. M. W., & Micha, D. (2025). Compound KTI-2338 Inhibits ACVR1 Receptor Signaling in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121590