Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6″-Modified Apramycin Derivatives to Overcome Aminoglycoside Resistance

Abstract

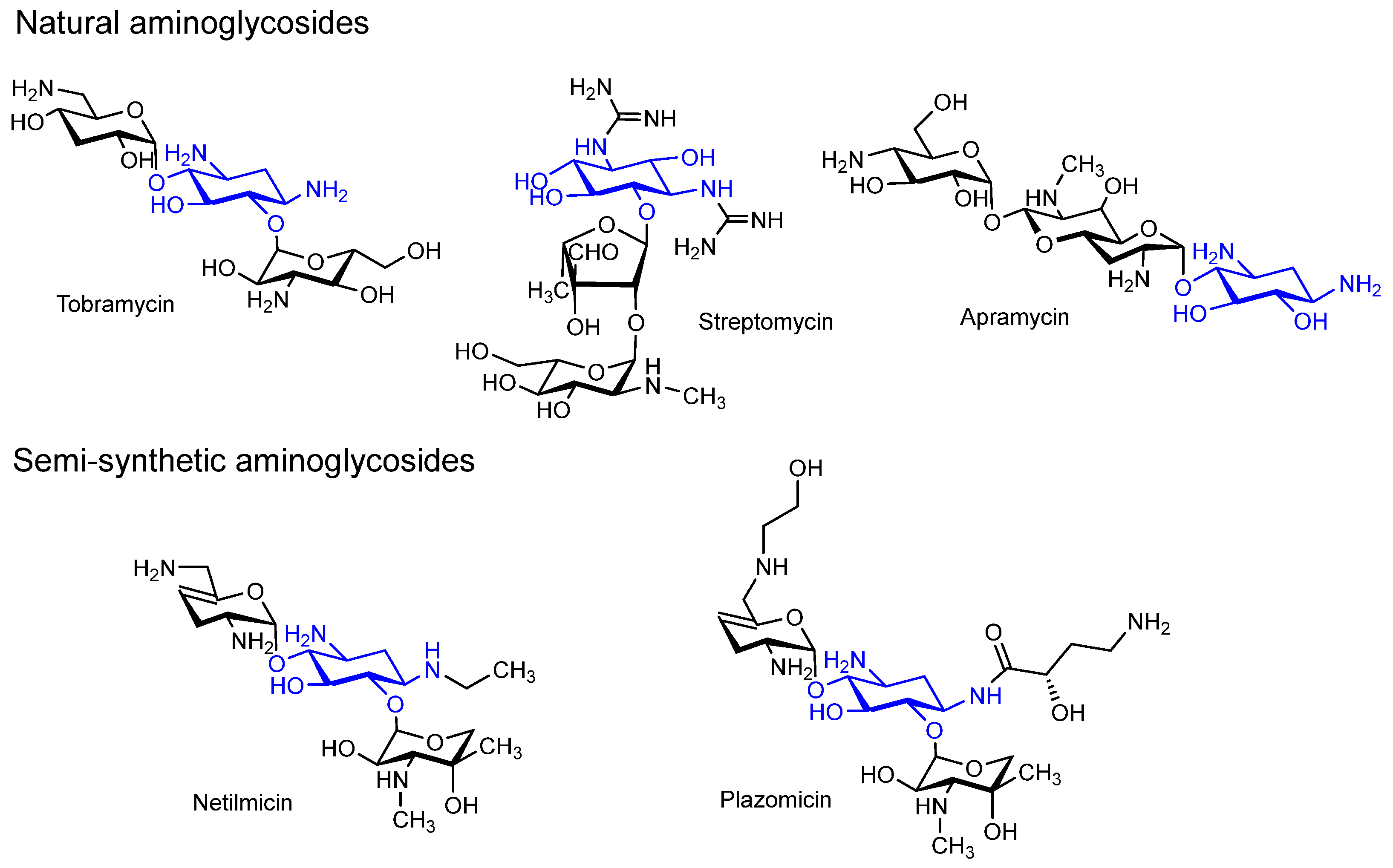

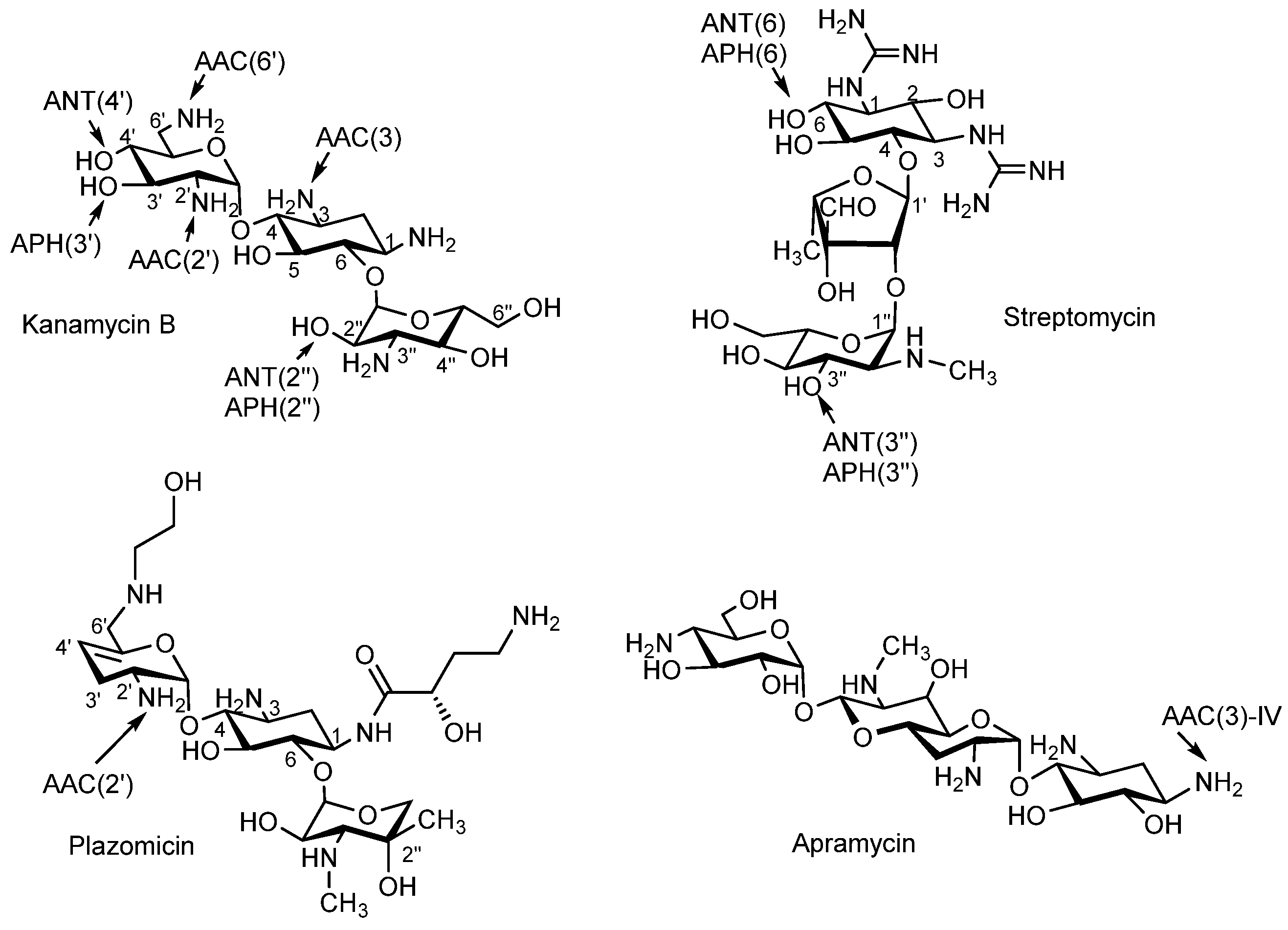

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

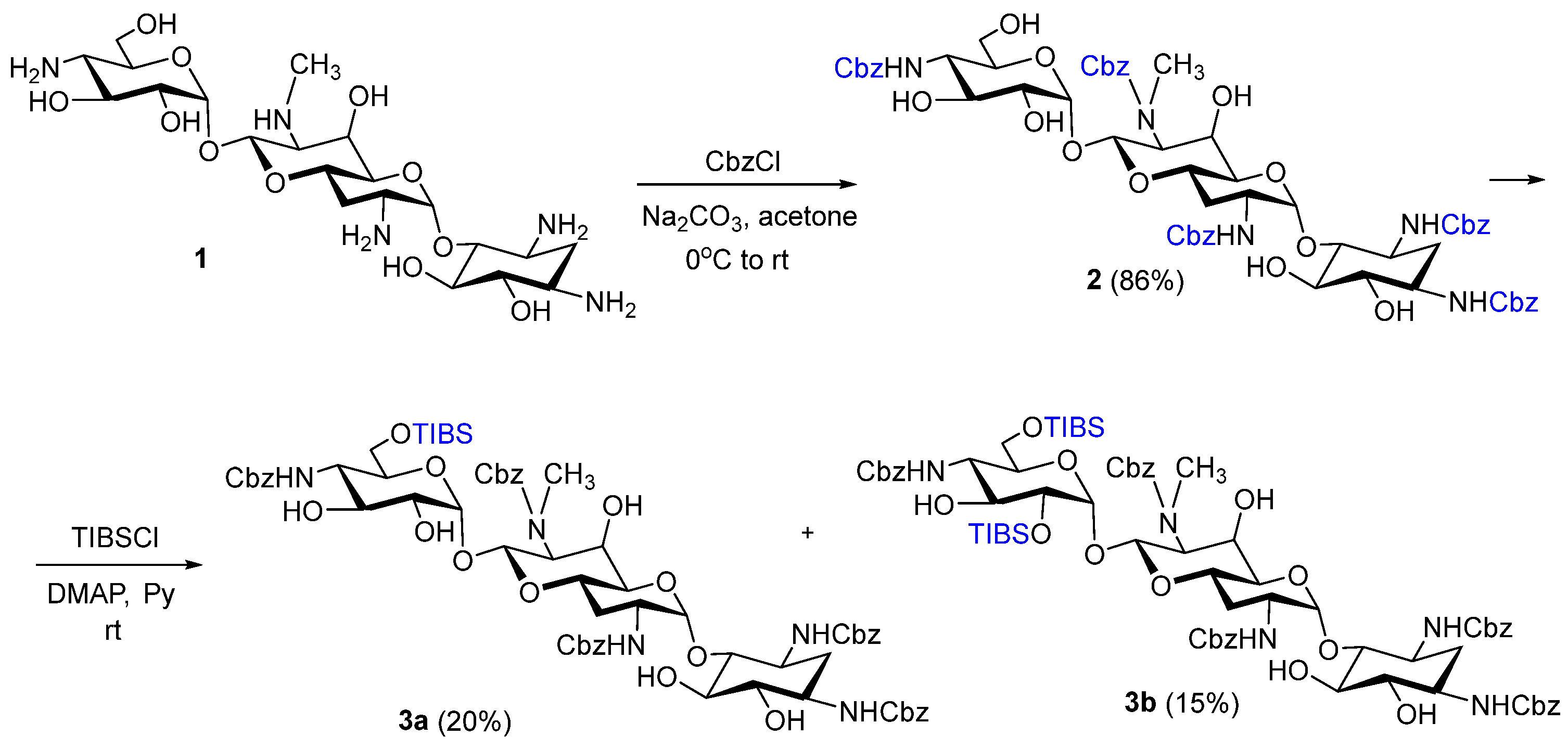

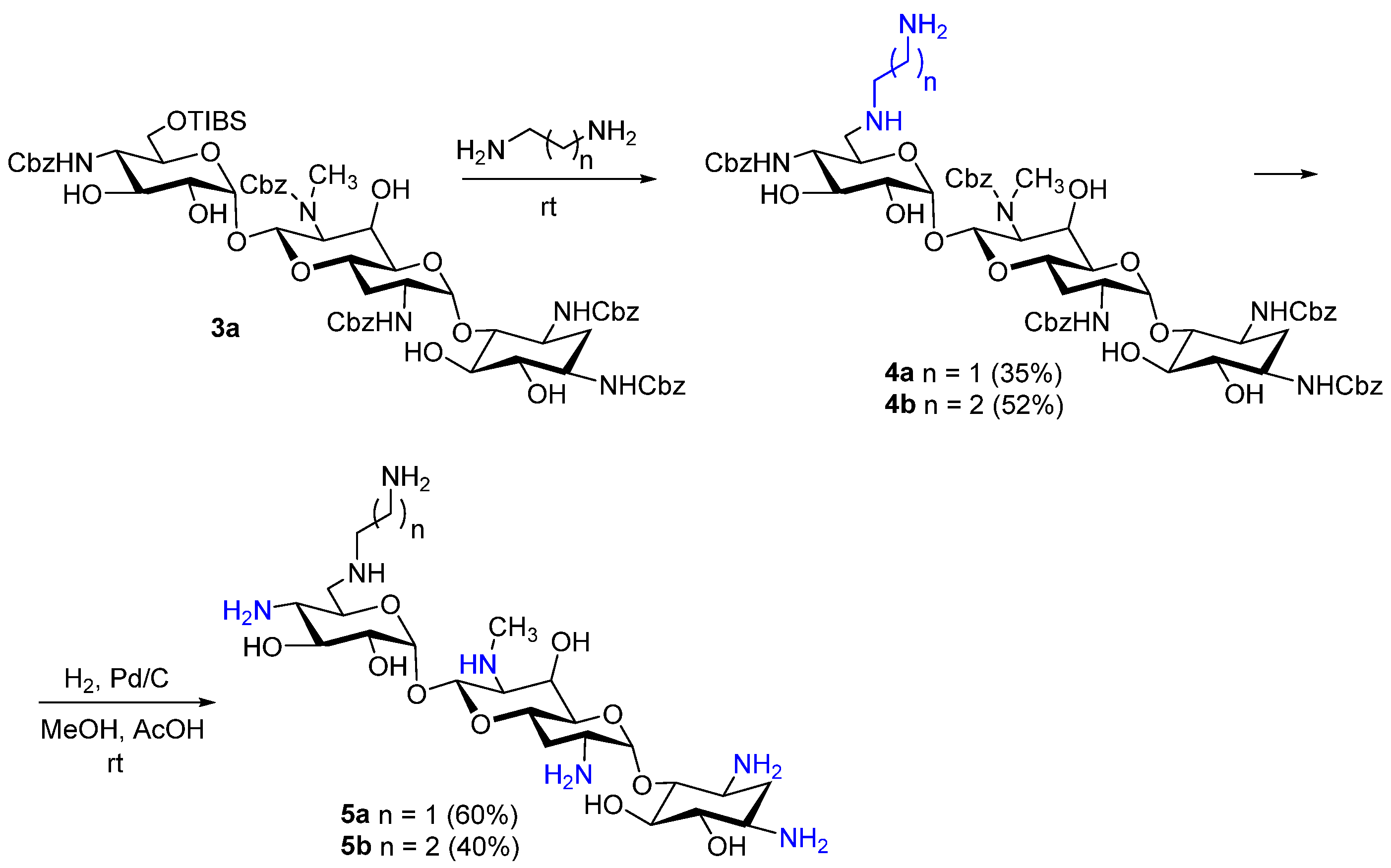

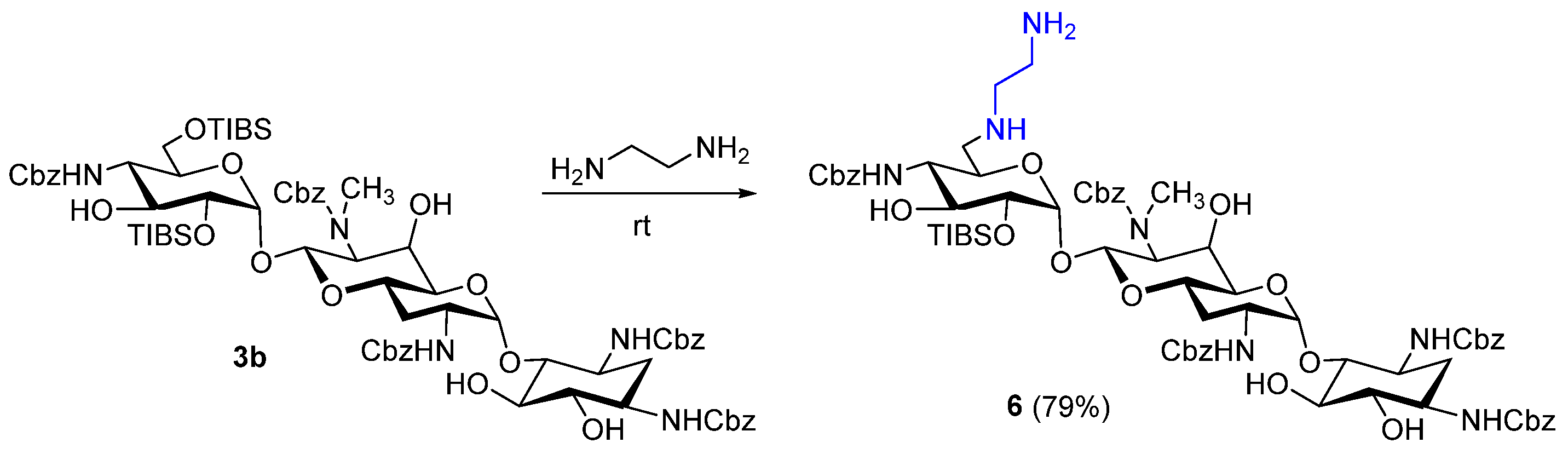

2.1. Chemistry

Instruments, General Information, and Synthetic Procedures

2.2. Microorganisms and the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Evaluation

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2.2. Assay Setting

2.3. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Against Aminoglycoside-Resistant Mutants of E. coli

2.4. Cell-Free Translation Inhibition Assay

2.5. Determination of Translation Accuracy Using Reporters

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assay

3. Results and Discussion

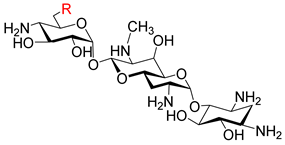

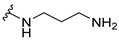

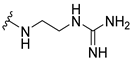

3.1. Chemistry

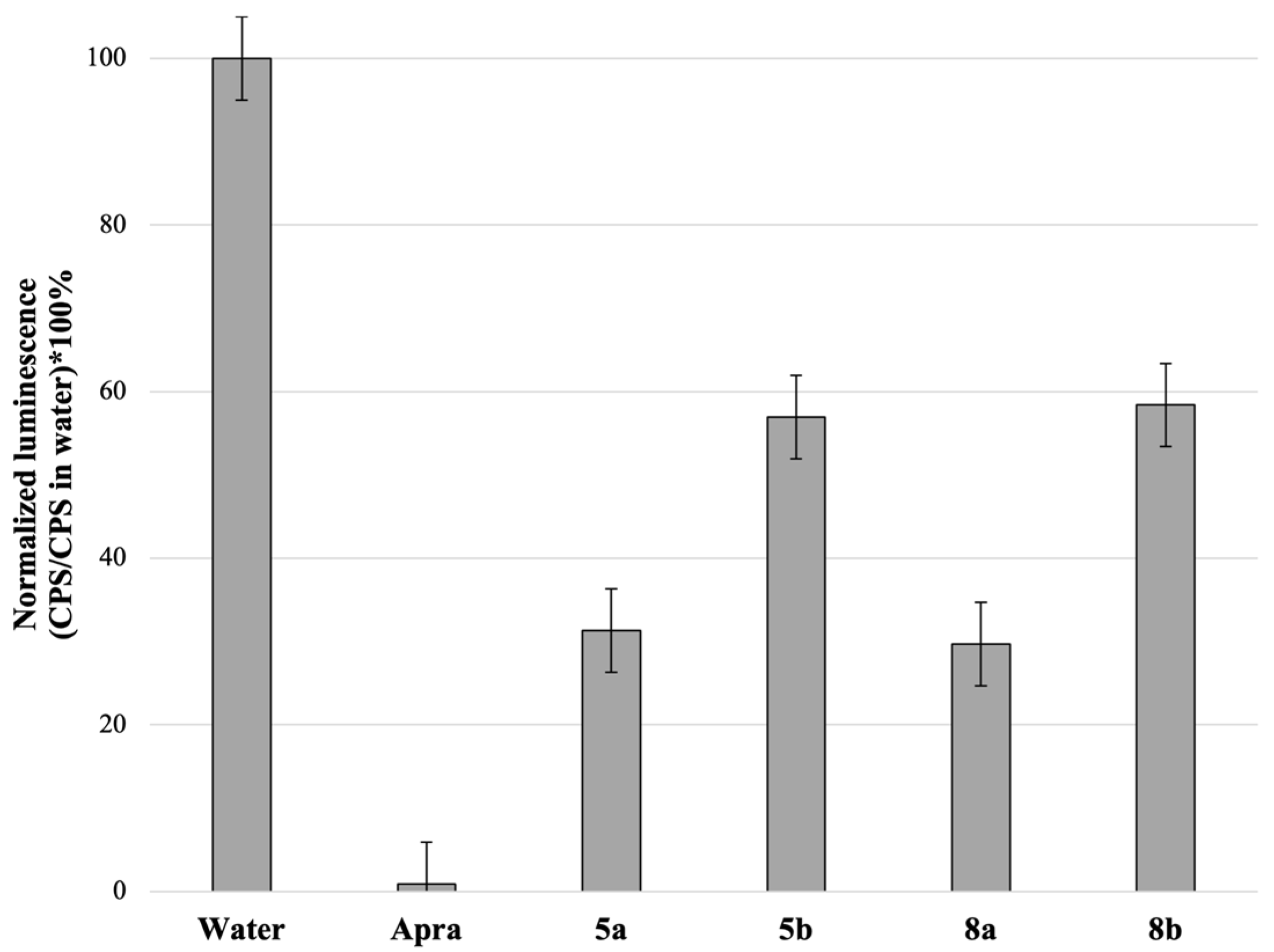

3.2. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Studies

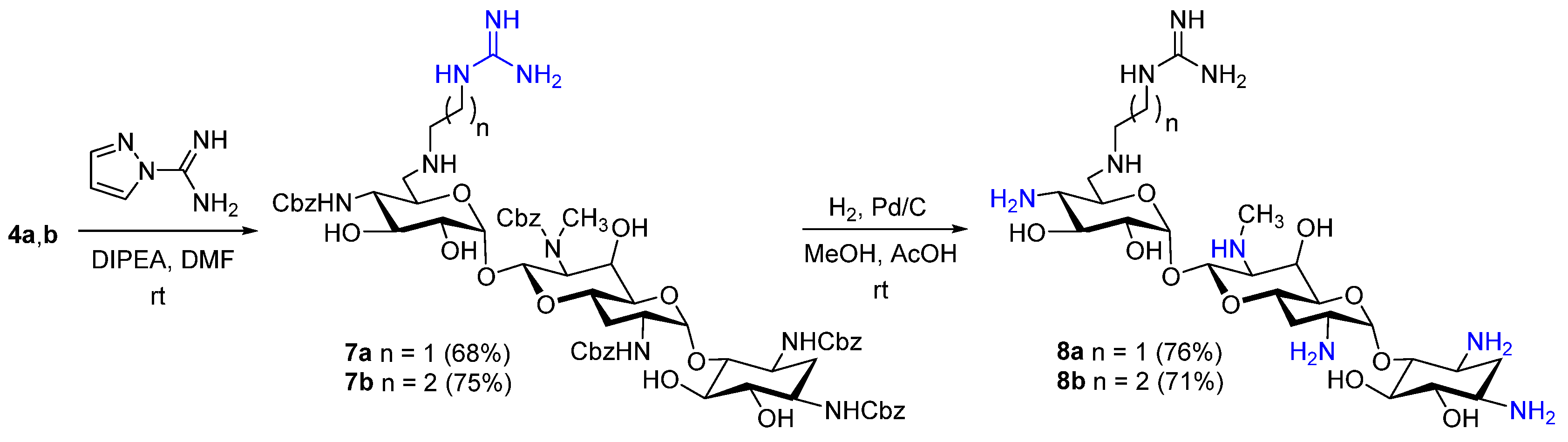

3.3. Mechanism of Action

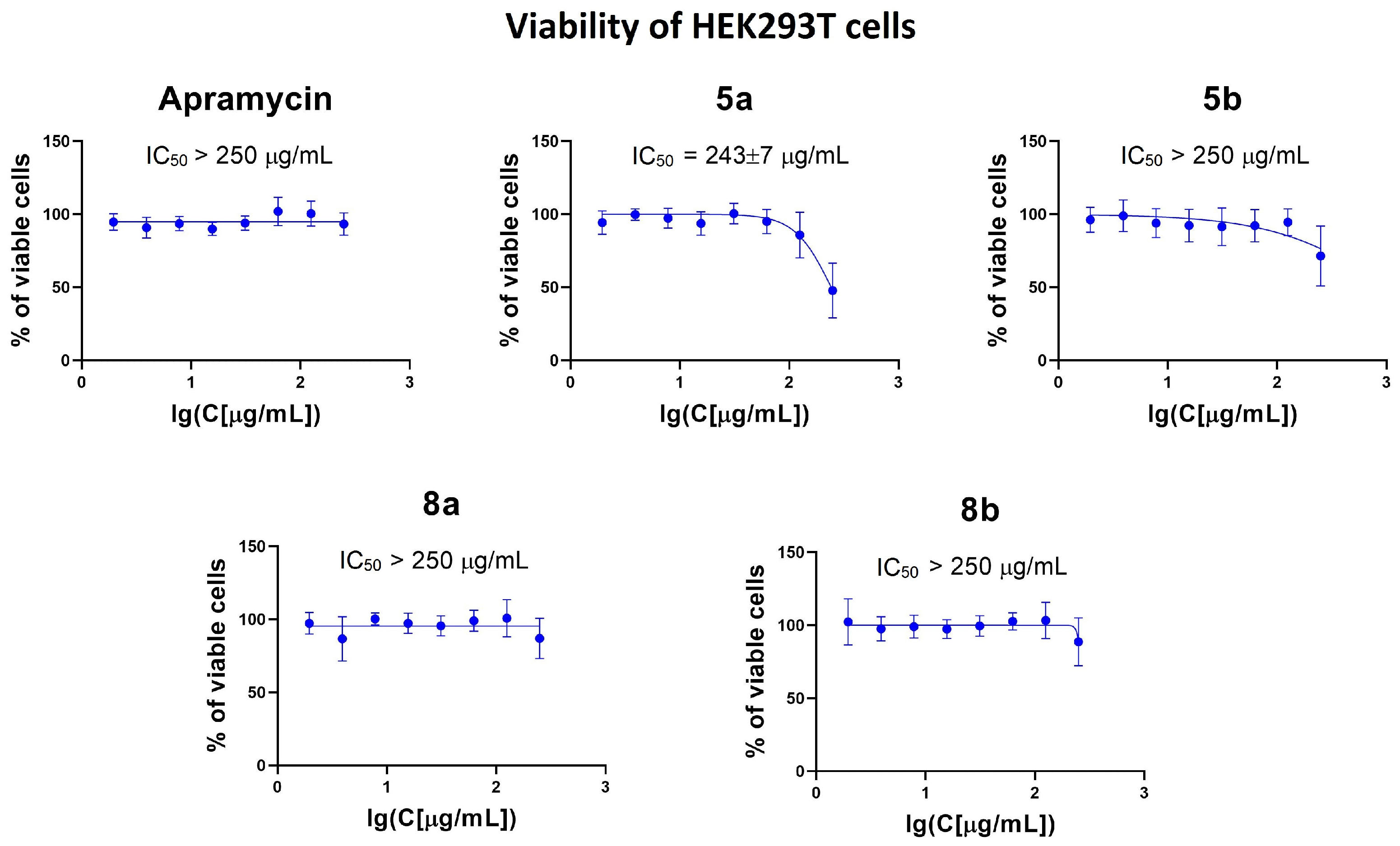

3.4. Cytotoxicity Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG | Aminoglycoside |

| AME | aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme |

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance |

| Cbz | Benzyloxycarbonyl |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulfoxide |

| IC50 | the amount of a drug that causes the inhibition of the growth of 50% of cells |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| HRMS (ESI) | high-resolution mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization |

| MDR | multidrug resistance |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| TIBS | 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl |

| TLC | thin layer chromatography |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Pontefract, B.A.; Ho, H.T.; Crain, A.; Kharel, M.K.; Nybo, S.E. Drugs for Gram-Negative Bugs from 2010–2019: A Decade in Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesudason, T. WHO publishes updated list of bacterial priority pathogens. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M.; Serio, A.W.; Kane, T.R.; Connolly, L.E. Aminoglycosides: An overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a027029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garneau-Tsodikova, S.; Labby, K.J. Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: Overview and perspectives. Medchemcomm 2016, 7, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryden, R.; Moore, B.J. The in vitro activity of apramycin, a new aminocyditol antibiotic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1977, 3, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Shi, X.; Lv, J.; Niu, S.; Cheng, S.; Du, H.; Yu, F.; Tang, Y.W.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Zhang, H.; et al. In vitro activity of apramycin against carbapenem-resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, A.D.; Smith, K.P.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Berg, A.H.; McCoy, C.; Kirby, J.E. In vitro apramycin activity against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 88, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zong, Z. In vitro activity of neomycin, streptomycin, paromomycin and apramycin against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae clinical strains. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yan, J.; Long, S.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, G.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Wang, G. Apramycin has high in vitro activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 73, 001854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Truelson, K.A.; Stewart, I.A.; O’Doherty, G.A.; Kirby, J.E. Enhanced Activity of Apramycin and Apramycin-Based Combinations Against Mycobacteroides abscessus. bioRxiv 2025, dkaf433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, T.; Ng, C.L.; Lang, K.; Sha, S.H.; Akbergenov, R.; Shcherbakov, D.; Meyer, M.; Duscha, S.; Xie, J.; Dubbaka, S.R.; et al. Dissociation of antibacterial activity and aminoglycoside ototoxicity in the 4-monosubstituted 2-deoxystreptamine apramycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10984–10989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhas, M.; Widlake, E.; Teo, J.; Huseby, D.L.; Tyrrell, J.M.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Ercan, O.; Petersson, A.; Cao, S.; Aboklaish, A.F.; et al. In vitro activity of apramycin against multidrug-, carbapenem-and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Cao, S.; Nilsson, A.; Erlandsson, M.; Hotop, S.K.; Kuka, J.; Hansen, J.; Haldimann, K.; Grinberga, S.; Berruga-Fernández, T.; et al. Antibacterial activity of apramycin at acidic pH warrants wide therapeutic window in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections and acute pyelonephritis. EBioMedicine 2021, 73, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updat. 2010, 13, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, A.; Franco, S.D.; Donatiello, V.; Maffei, V.; Fittipaldi, C.; Fiore, M.; Coppolino, F.; Sansone, P.; Pace, M.C.; Passavanti, M.B. Plazomicin against multidrug-resistant bacteria: A scoping review. Life 2022, 12, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordeleau, E.; Stogios, P.J.; Evdokimova, E.; Koteva, K.; Savchenko, A.; Wright, G.D. ApmA is a unique aminoglycoside antibiotic acetyltransferase that inactivates apramycin. MBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirke, J.C.K.; Rajasekaran, P.; Sarpe, V.A.; Sonousi, A.; Osinnii, I.; Gysin, M.; Haldimann, K.; Fang, Q.J.; Shcherbakov, D.; Hobbie, S.N.; et al. Apralogs: Apramycin 5-O-glycosides and ethers with improved antibacterial activity and ribosomal selectivity and reduced susceptibility to the aminoacyltransferase (3)-IV resistance determinant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 142, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, K.; Zatonsky, G.; Grammatikova, N.; Osterman, I.; Razumova, E.; Shchekotikhin, A.; Tevyashova, A. Synthesis of 6 ″-modified kanamycin A derivatives and evaluation of their antibacterial properties. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, K.S.; Zatonsky, G.V.; Razumova, E.A.; Ipatova, D.A.; Lukianov, D.A.; Sergiev, P.V.; Grammatikova, N.E.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of New 6 ″-Modified Tobramycin Derivatives. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI M07; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2015 (M07-A10). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests For bacteria that Grow Aerobically. Approved Standard, 10th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Berwyn, PA, USA, 2015.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standarts Institute M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2020. Available online: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/ (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Routine and Extended Internal Quality Control for MIC Determination and Disk Diffusion as Recommended by EUCAST; 2023, Version 13.0; The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2023; Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Hadidi, K.; Wexselblatt, E.; Esko, J.D.; Tor, Y. Cellular uptake of modified aminoglycosides. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Ara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Takai, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Baba, M.; Datsenko, K.A.; Tomita, M.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006.0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6640–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, I.A.; Komarova, E.S.; Shiryaev, D.I.; Korniltsev, I.A.; Khven, I.M.; Lukyanov, D.A.; Tashlitsky, V.N.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Efremenkova, O.V.; Ivanenkov, Y.A.; et al. Sorting out antibiotics’ mechanisms of action: A double fluorescent protein reporter for high-throughput screening of ribosome and DNA biosynthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7481–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaporojets, D.; French, S.; Squires, C.L. Products transcribed from rearranged rrn genes of Escherichia coli can assemble to form functional ribosomes. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 6921–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukianov, D.A.; Buev, V.S.; Ivanenkov, Y.A.; Kartsev, V.G.; Skvortsov, D.A.; Osterman, I.A.; Sergiev, P.V. Imidazole Derivative As a Novel Translation Inhibitor. Acta Naturae. 2022, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

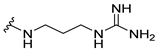

- Fair, R.J.; Hensler, M.E.; Thienphrapa, W.; Dam, Q.N.; Nizet, V.; Tor, Y. Selectively guanidinylated aminoglycosides as antibiotics. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsufyeva, E.N.; Shchekotikhin, A.E. Key areas of antibiotic research conducted at the Gause Institute of New Antibiotics. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 3523–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogre, A.; Veetil, R.T.; Seshasayee, A.S.N. Modulation of global transcriptional regulatory networks as a strategy for increasing kanamycin resistance of the translational elongation factor-G mutants in Escherichia coli. G3 2017, 7, 3955–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogre, A.; Sengupta, T.; Veetil, R.T.; Ravi, P.; Seshasayee, A. Genomic analysis reveals distinct concentration-dependent evolutionary trajectories for antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. DNA Res. 2014, 21, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzynski, S.; Cannon, M.; Cundliffe, E.; Chahwala, S.B.; Davies, J. Effects of apramycin, a novel aminoglycoside antibiotic on bacterial protein synthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1979, 99, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milicaj, J.; Hassan, B.A.; Cote, J.M.; Ramirez-Mondragon, C.A.; Jaunbocus, N.; Rafalowski, A.; Patel, K.R.; Castro, C.D.; Muthyala, R.; Sham, Y.Y.; et al. Discovery of first-in-class nanomolar inhibitors of heptosyltransferase I reveals a new aminoglycoside target and potential alternative mechanism of action. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, G.N.; Kralj, J.M. Membrane voltage dysregulation driven by metabolic dysfunction underlies bactericidal activity of aminoglycosides. Elife 2020, 9, e58706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Wierzbowski, J.; Cottarel, G.; Collins, J.J. Mistranslation of membrane proteins and two-component system activation trigger antibiotic-mediated cell death. Cell 2008, 135, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

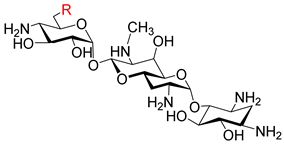

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | MIC a, µg/mL | |||

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | E. coli ATCC 25922 | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | M. smegmatis ATCC 607 | ||

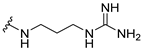

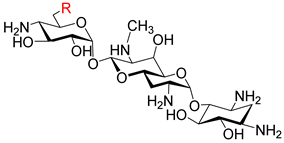

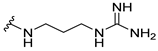

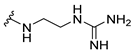

| 5a |  | 2 | 2 | 8 | 0.25 |

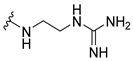

| 5b |  | 2 | 2 | 16 | 0.25 |

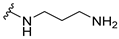

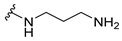

| 8a |  | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | 0.125 |

| 8b |  | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | 0.125 |

| Apramycin (1) | OH | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.125 |

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | MIC, µg/mL | ||||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | E. coli MAR17-1350 a | K. pneumoniae APEX-5 b | K. pneumoniae MAR14-3395 c | K. pneumoniae MAR18-1752 d | ||

| 5a |  | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 5b |  | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 8a |  | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 8b |  | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Apramycin (1) | OH | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tobramycin | - | 0.5 | >128 | 32 | >128 | >128 |

| Gentamycin | - | 0.25 | >128 | 32 | >128 | >128 |

| Kanamycin A | - | 2 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | MIC, µg/mL | ||||

| E. coli JW5503 kanS | E. coli JW5503 EF-G P610T | E. coli JW5503 KanR | E. coli JW5503 SmR | E. coli JW5503 ApmR | ||

| 5a |  | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | >256 |

| 5b |  | 32 | 64 | 32 | 32 | >256 |

| 8a |  | 8 | 32 | 8 | 16 | >256 |

| 8b |  | 16 | 64 | 16 | 32 | >256 |

| Apramycin (1) | OH | 8 | 64 | 4 | 8 | >256 |

| Tobramycin | - | 2 | 16 | 2 | 4 | >256 |

| Streptomycin | - | 4 | 8 | 4 | >256 | 4 |

| Kanamycin A | - | 4 | 64 | >256 | 8 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shapovalova, K.S.; Zatonsky, G.V.; Razumova, E.A.; Dagaev, N.D.; Lukianov, D.A.; Grammatikova, N.E.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6″-Modified Apramycin Derivatives to Overcome Aminoglycoside Resistance. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121583

Shapovalova KS, Zatonsky GV, Razumova EA, Dagaev ND, Lukianov DA, Grammatikova NE, Tikhomirov AS, Shchekotikhin AE. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6″-Modified Apramycin Derivatives to Overcome Aminoglycoside Resistance. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121583

Chicago/Turabian StyleShapovalova, Kseniya S., Georgy V. Zatonsky, Elizaveta A. Razumova, Nikolai D. Dagaev, Dmitrii A. Lukianov, Natalia E. Grammatikova, Alexander S. Tikhomirov, and Andrey E. Shchekotikhin. 2025. "Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6″-Modified Apramycin Derivatives to Overcome Aminoglycoside Resistance" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121583

APA StyleShapovalova, K. S., Zatonsky, G. V., Razumova, E. A., Dagaev, N. D., Lukianov, D. A., Grammatikova, N. E., Tikhomirov, A. S., & Shchekotikhin, A. E. (2025). Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6″-Modified Apramycin Derivatives to Overcome Aminoglycoside Resistance. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121583