1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women globally [

1]. In 2022, over 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer were reported in women, and 670,000 deaths [

2]. The cases are expected to increase by 38 percent globally by 2050, with annual deaths from the disease projected to rise by 68 percent, according to a new report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer [

3]. While the incidence is relatively lower in Eastern Europe, South America, Southern Africa, and Western Asia, breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer in women in these regions.

Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs) serve as an alternative to Tamoxifen (TX) for adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer. Available options include Anastrozole and Letrozole (LZ) for five years and Anastrozole and Exemestane following two to three years of TX treatment for a total of five years of hormonal therapy. It is recommended that five years of LZ therapy be considered following an initial five years of TX. Patients on AIs should be regularly monitored for bone density, cardiovascular risk, and treatment outcomes [

4].

LZ is rapidly and completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with food having no significant impact on its absorption. It is slowly metabolized into an inactive metabolite, and its glucuronide conjugate is primarily excreted via renal pathways, representing the primary clearance method. Approximately 90% of radiolabeled LZ is excreted in the urine. The terminal elimination half-life of LZ is approximately two days, and steady-state plasma concentrations are reached within 2–6 weeks of daily 2.5 mg dosing. At steady state, plasma levels are 1.5–2 times higher than predicted from a single dose, showing mild non-linearity in LZ pharmacokinetics when administered daily. These steady-state levels remain consistent over prolonged periods, although continuous accumulation does not occur. LZ is weakly bound to plasma proteins and has a large volume of distribution, approximately 1.9 L/kg [

5,

6].

Long-term oral administration of LZ may cause several side effects in women, including hot flashes and sweating (affecting about 30% of women), joint pain (20%), fatigue (20%), mild skin rashes (10%), headaches (10%), dizziness (10%), nausea (10%), fluid retention causing swelling in the ankles or fingers (10%), loss of appetite, indigestion, hair thinning, diarrhea, constipation, vaginal dryness, decreased libido, mood changes, cough, and breathlessness (affecting fewer than 10% of women) [

7]. Additionally, there may be a slight increase in cholesterol levels and a reduction in bone density due to the prolonged absence of estrogen, affecting fewer than 5% of women. Fluctuations in LZ plasma levels after oral dosing often intensify side effects [

8].

One potential solution to such a challenge with orally administered LZ is its administration utilizing transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS), which maintain a constant drug level, potentially reducing side effects. Weekly application and easy discontinuation improve adherence, making TDDS an appealing option. LZ is a white to yellowish crystalline powder freely soluble in dichloromethane, slightly soluble in ethanol, and practically insoluble in water (102 mg/L at 25 °C). It has a molecular weight of 285.31 g/mol, an empirical formula of C

17H

11N

5, and a melting range of 184–185 °C. It is categorized as a lipophilic drug with a log K o/w of 2.22 [

9]. LZ’s low molecular weight, good lipophilicity, and small daily dose make it an excellent candidate for TDDS. Recent studies have demonstrated that LZ formulated as a drug-in-adhesive transdermal patch offers prolonged activity and reduced dosing frequency, which enhances patient compliance [

10,

11].

Nano-dispersed systems like liposomes, nanoemulsions, and lipid nanoparticles are increasingly used for controlled release and skin targeting [

12]. These nano-drug lipid carriers improve drugs’ physical and chemical stability by preventing water from entering the lipid particle core, enhancing percutaneous absorption, and enabling controlled release and targeting [

13,

14,

15]. Thus, nano-lipid carriers offer strong potential for TDDS by passing through ≤100 nm pores, reducing clearance, and allowing deep, targeted, and sustained drug deposition [

16,

17].

Individually, the components of nanoemulsions can enhance transdermal drug delivery, and their combination creates a synergistic effect that significantly improves drug flux across the skin and bioavailability [

18,

19,

20]. Also, from a pharmaceutical technology perspective, nano-dispersed DDS offers a particulate system that can be produced using established high-pressure homogenization techniques, enabling industrial-scale production [

12]. Research also indicates that integrating a nano-dispersed system into a hydrogel can result in a thickened matrix formula for TDDS, further advancing this delivery method [

21,

22,

23].

Non-aqueous nanoemulgels are currently emerging as a promising class of nanocarriers for transdermal drug delivery because they integrate the high solubilization potential of nanoemulsions with the spreadability and bioadhesion of gels, while avoiding water-related instabilities such as hydrolysis and microbial growth [

24]. These systems are particularly advantageous for moisture-sensitive or lipophilic active pharmaceutical ingredients, offering enhanced chemical stability, prolonged residence time, and improved skin permeation [

11,

25]. Recent studies show these systems can include permeation enhancers, optimize droplet size, and provide controlled release with higher skin flux than aqueous formulations [

15,

26]. Moreover, patented designs and proof-of-concept applications, including non-aqueous nanoemulgels for transdermal delivery of potent small molecules and localized therapy, underscore their translational potential as patient-friendly, non-invasive drug delivery platforms [

15,

18].

This research focuses on developing and in vivo testing newly formulated non-aqueous nanoemulgels designed for topical and transdermal delivery of the potent aromatase inhibitor LZ. The drug flux optimization was achieved by incorporating nanoemulsions and penetration enhancers into TDDS while exploring the synergistic effects of this combination.

3. Results & Discussions

3.1. UPLC Instrumentation and Conditions

A mobile phase composed of acetonitrile: water (35:65

v/

v) and a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min was the optimal composition that resulted in a sharp symmetrical LZ peak (

Figure A1). The average retention time was 1.8 min with a 0.12% RSD.

3.2. Method Validation

System suitability: In all measurements, the peak area showed a variation of less than 2.0% while the average retention time was found to be 1.7 min with an RSD of 0.21%. The capacity and tailing factors were 3 and 1, respectively, as evidence of the method’s suitability for the reported application.

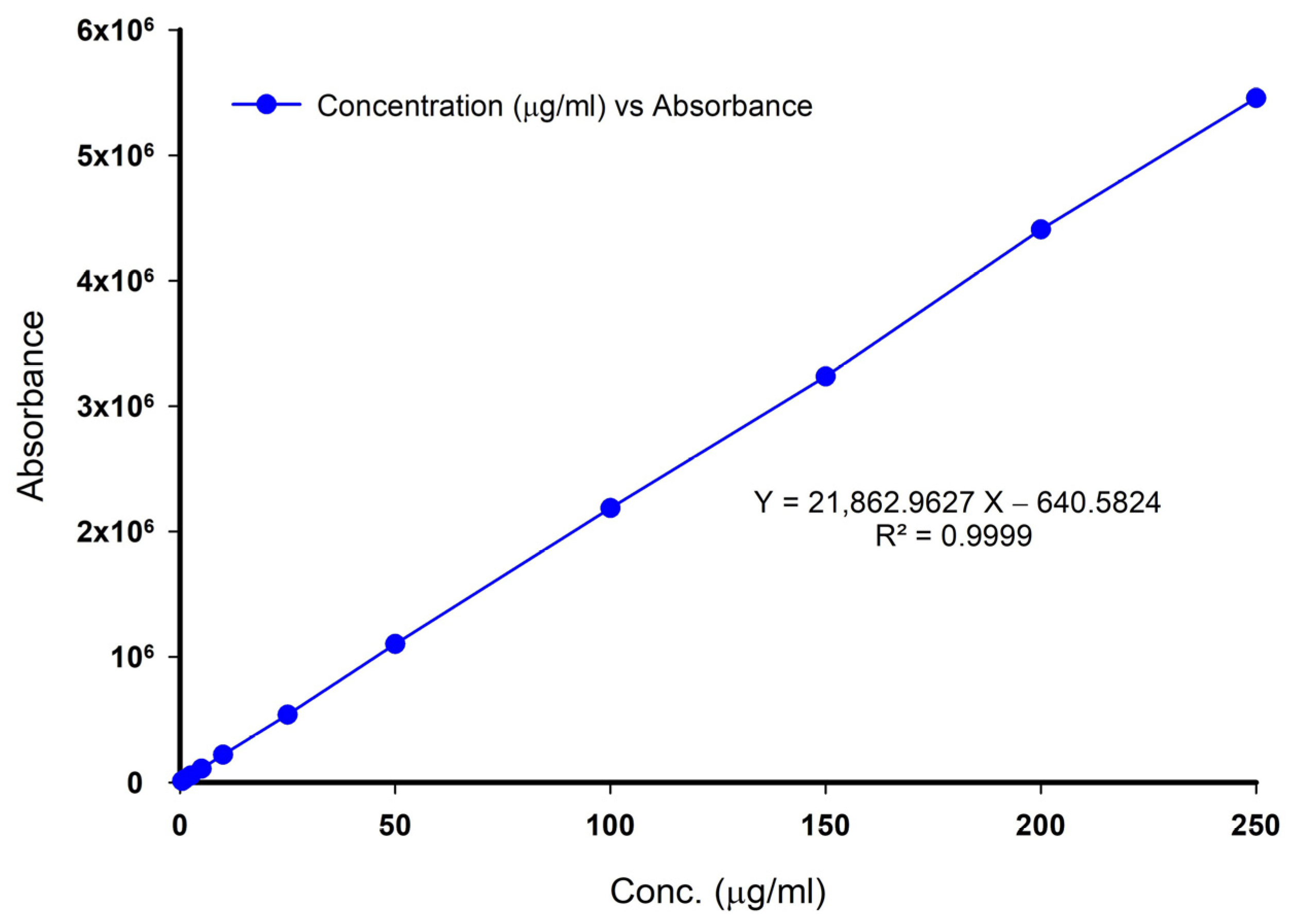

Linearity, range, and detection limits: The calibration curve for LZ was linear over a concentration range of 2.5–250 µg/mL with a reported correlation coefficient R

2 equivalent to 0.9999, as shown in

Figure A2. Following the ICH guideline, the lowest detectable and quantifiable concentrations of LZ using the assay method were found to be 0.025 µg/mL and 0.125 µg/mL, respectively.

Accuracy & Precision: The percentage recovery showed 102.4, 99.6, 99.8, and 102.0% for spiked amounts of 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 3 mg/10 mL nanoemulgel, respectively.

Table A1 and

Table A2 show the accuracy and precision assessment results after analyzing nanoemulgels. As per the results shown, the method was found to be precise (RSD < 2%) and accurate.

There was no interference between the LZ peak and any of those of the emulsion’s components, which strongly indicates the ability of the reported method to selectively and specifically be used for the analysis of LZ in emulsion formulations containing common oils, surfactants, and co-surfactant mixtures. Similar results were observed for the assay of LZ in nanoemulgels containing various penetration enhancers. As for the possible interference of LZ with PTFE filters, it was found that the percentage recovery of standard aqueous solutions following filtration through PTFE was 99.5% and 99.3%, respectively. The method’s robustness was found acceptable to changes in wavelength, flow rate, and mobile phase composition (%RSD < 2).

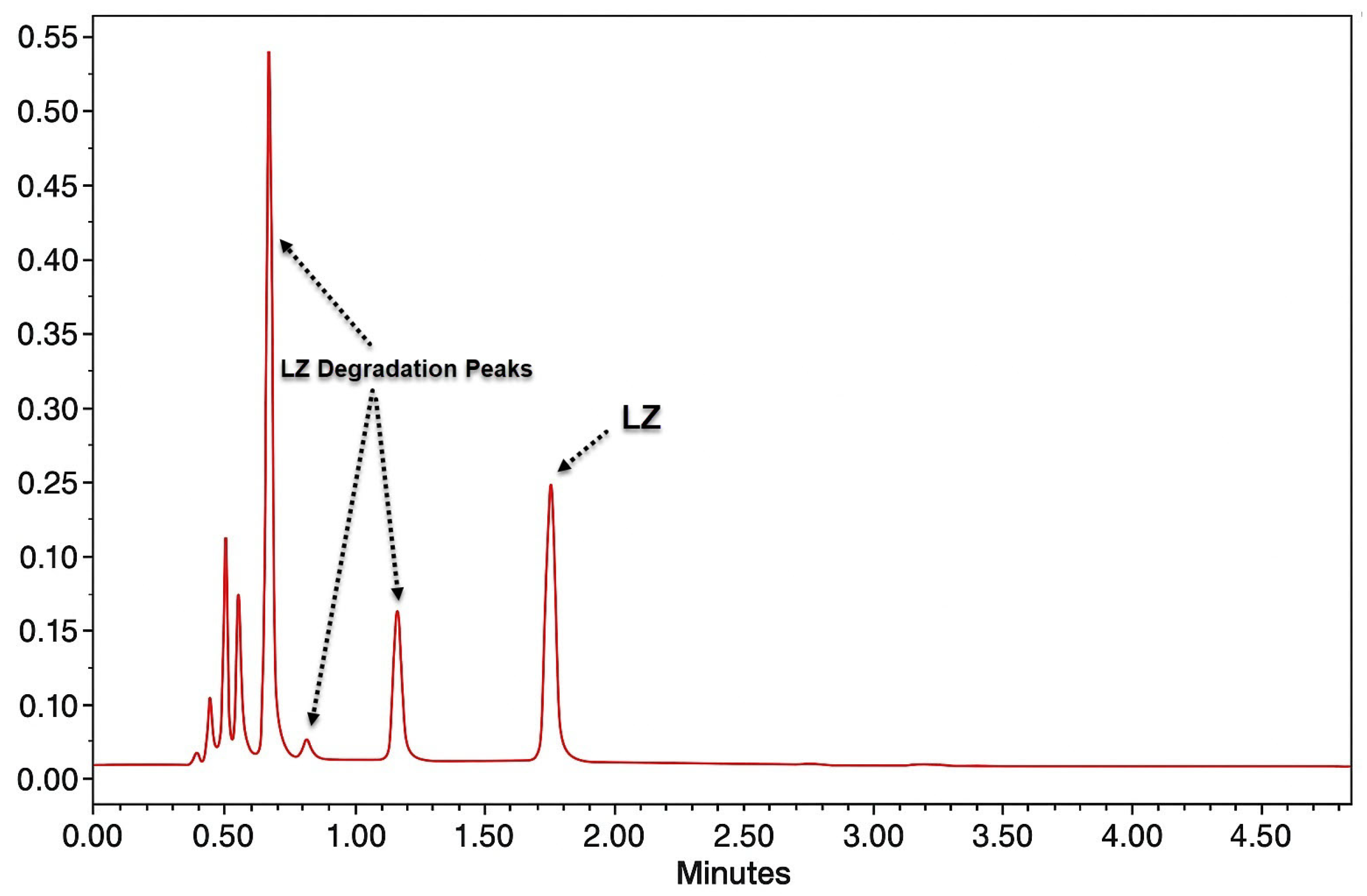

3.3. Degradation Studies/Specificity

Table A3 reports the percentage of drug recovered/decomposed under the different stress conditions used in the study. LZ was stable under UV-radiation and thermal conditions and showed insignificant instability under acidic and oxidative stress (% decomposed ~ 1.5%). LZ was most sensitive to basic conditions (71.6% decomposition). This instability could be related to the presence of a triazole ring in its structure. In all the analyses, no interference of the LZ peak with any degradation products was observed (

Figure A3).

The chromatograms and the amount of LZ recovered after different treatments show that LZ was stable in all other conditions except the alkaline hydrolysis condition. Furthermore, the components of various nanoemulgels did not interfere in the analysis of the standard solution of LZ, nor under forced degradation conditions. The retention time for LZ was 1.8 min for both LZ nanoemulgel samples and standard solutions. The absence of co-eluting degradants and nanoemulgel additives (solvents, surfactants, penetration enhancers, and polymers) was observed with almost purity of 100% for the pure and sample LZ peaks.

3.4. Solubility Studies

The solubility of LZ in water, oily solvents, and cosolvents at 32 °C and 37 °C is reported in

Table 1. LZ showed a very poor aqueous solubility in water. LZ is a relatively nonpolar molecule that cannot effectively break the lattice structure of water; hence, the aqueous solubility of LZ is low. As shown in

Table 1, the solubility of LZ in oily vehicles is much higher than in water. Oily vehicles are essential components of emulsions and emulgels and play a solubilization role for LZ.

The solubility of LZ was found to be the highest in TC and was many times more soluble than in other solvents studied in this investigation. The temperature was also found to affect the solubility of LZ, which increased significantly upon increasing the temperature by 5 °C, as reported in

Table 1. The most effective was prominent in the case of TC, which rendered it suitable for use as a cosolvent in formulations of LZ emulgels.

3.5. Medium Selection in the Receptor Chamber

The primary criterion for selecting the receptor medium in the diffusion studies was the solubility of LZ in the medium and its capacity to maintain sink conditions for LZ diffusing from the emulgel formulations across the membranes. Therefore, the solubility of LZ in different compositions of phosphate buffer of pH 6.8 (PHB) and TC was tested. It was found that a solution containing 20% TC in PHB is suitable for achieving sink conditions and is also near the physiological condition of the skin. In addition, the medium was replaced every 24 h with fresh solution, a step that kept sink condition fulfilled during the run of the diffusion studies.

Figure 3 shows the solubility of LZ in TC/PHB at 32 °C, demonstrating that LZ solubility increases upon increasing the percentage of TC.

3.6. LZ Solutions’ Stability in Various Pharmaceutical Additives

The development of LZ nanoemulgels required a comprehensive screening of the solvents and additives used to investigate which have proven to be stable with LZ.

Table 2 reports the findings from the stability of LZ solutions in different pharmaceutical additives examined by storing them for a month at 50 °C. It was determined that LZ sample solutions in water, phosphate buffer, alcohols, propylene glycol (PG), Labrasol

®, and TC had high stability. But for the first time, LZ was discovered to be unstable in PEG 400. PEG’s hydrophilicity and molecular interactions can alter the drug’s solubility and crystal structure, potentially leading to degradation, reduced effectiveness, or even forming a less stable complex [

32]. As a result, PG and TC were used in place of PEG 400 as cosolvents in this investigation.

3.7. Stability of LZ in the Receiving Medium at 32 °C

The standard LZ solution in the receiving medium remained stable for up to 21 days at 32 °C. Experiments were performed in duplicate, with the mean initial concentration measured at 207.14 µg/mL and 207.22 µg/mL after 21 days, confirming the excellent stability of LZ in the receiving medium.

3.8. Stability of Sample Solutions

The stability of sample solutions remained at 48 h in the refrigerator at 5 °C or at room temperature, indicating excellent stability (99.9 ± 1.3% and 99.4 ± 1.7%, respectively). The results confirm that the sample solutions used during the assays were stable up to 48 h at room temperature and in the refrigerator.

3.9. Formulation of Nanoemulgels

The main objective of NEMGs formulation is to make drugs more soluble and permeable across biological membranes. The nano-sized droplets in the nanoemulsion boost the drug’s permeation, adding to the synergistic effects of surfactants, co-surfactants, and permeation enhancers. The hydrogel component of NEMGs improves the product’s viscosity, spreadability, and physical stability for TDDS. The cosolvents in the NEMGs also increase the solubility of the drugs. This results in TDDS developing improved pharmacokinetic properties, protecting patients from the systemic side effects commonly associated with oral drug administration. The issue of nanoemulsions being less stable than microemulsions is overcome by including a gelling agent, which produces stable NEMGs [

18,

23,

33].

This study used several non-aqueous components, including oils, surfactants, and polymers [

15]. Sepineo P600

® is a milky suspension of acrylamide/sodium acryloyldimethyl taurate copolymer that gels on contact with hydrophilic media, containing isohexadecane and polysorbate 80, serving as a surfactant. Glyceryl monooleate (GMO), widely utilized in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, was included as a cosurfactant. Due to its amphiphilic nature, possessing both hydrophilic and lipophilic domains, GMO functions effectively as an emulsifier and emulsion stabilizer [

34]. In addition, GMOs have been reported to enhance transdermal drug delivery by interacting with the stratum corneum, which promotes ceramide extraction and increases lipid fluidity, thereby facilitating drug permeation [

35]. Various commercial grades of GMO are available, including Peceol

® (40% GMO), Capmul

® (60% GMO), and Myverol

® (90% GMO). According to suppliers’ information, these products also contain oleic acid di- and triglycerides, along with trace levels of free fatty acids and glycerol. The cosolvents PG and TC were incorporated as the polar, hydrophilic, non-aqueous components of the nanoemulgel system. As previously demonstrated in

Table 2, LZ solubility was markedly enhanced in the presence of TC and moderately improved with PG. Notably, both cosolvents have also been reported to act as penetration enhancers [

35]. Additional permeation enhancers included propylene glycol laurate (PGL), propylene glycol monocaprylate (PGMC), and Captex

® (coco-caprylate/caprate) as summarized in

Table 3 [

36,

37]. It was reported that if the nanoemulsion is between 50 and 200 nm, it appears clear and transparent. However, if it is 500 nm or larger, it will be milky or hazy [

18]. This observation was used as a guideline in this investigation. The formation of the nanoemulgel was indicated by the formation of a clear gel.

In the NEMGs matrix, up to 1.5%

w/

w LZ may be readily dissolved, as reported in

Table 3. Some formulas, such as F08, included 1.52%

w/

w LZ in a dissolved state. The solubility of LZ was due to the presence of both PG and TC in a concentration of at least 65%

w/

w. While the other GMO grades formed clear gels, NEMG, which included Peceol

® in the ratios reported in F07, did not. This result might be explained by the fact that Peceol

® included a higher percentage of glyceryl di- and trioleate, which produced a larger molar volume than GMO of Campul

® and Myverol

® and influenced the size of the emulsion droplets. The formulations without GMO (F08), Campul

®, and Myverol

® all produced clear gels, which showed the development of nanoemulgels. Transparent gels like F09 and F10 were formed when Campul

® and/or Myverol

® were mixed with Peceol

®. The observed texture of the gel indicated that the NEMGs with Myverol

® GMO were the stiffest gels, followed by the NEMGs containing Capmul

®, while the NEMGS with Peceol

® exhibited the least stiffness. The LZ components in the NEMGs were found not to influence the structure of the nanoemulgels. The NEMGs produced by Campul

® GMO were easier to handle; for this reason, they were selected for further investigation.

The number of NEMGs trials was reduced due to the lengthy runs, which took 15 days, and the large number of samples that needed analysis. For all NEMGS formulations, the PE proportion was maintained at the 5%

w/

w level. As reported in

Table 4, all penetration enhancers were added to the NEMGs and were found not to affect the gel’s transparency, resulting in a clear, thick gel.

3.10. Permeation Studies

In vitro permeation of LZ was conducted at 32 ± 1 °C using a Strat-M

® membrane and a phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 20%

v/

v Transcutol (TC). The Strat-M

® membrane is a multilayer synthetic barrier engineered to mimic the structure and composition of human skin, providing a cost-effective and reliable alternative for in vitro permeation studies. Previous reports have demonstrated a strong correlation between the permeation behavior across Strat-M

® and human stratum corneum, confirming its predictive value for percutaneous absorption studies [

28].

Uchida et al. reported that the diffusion and partition coefficients of various compounds through Strat-M

® closely matched those observed in excised human and rat epidermis [

38], supporting its use as a surrogate for biological membranes in permeation testing. Similarly, Haq et al. found comparable diffusion profiles, indicating that Strat-M

® is suitable for preliminary in vitro screening of transdermal formulations [

39]. In addition, Assaf et al. demonstrated a strong correlation between Strat-M

® and human skin in the transdermal evaluation of tamsulosin, further validating its suitability as a substitute membrane [

40].

While synthetic membranes can yield results that differ from those of human skin, especially for formulations relying on specific lipid or protein interactions or containing potent penetration enhancers, using the Strat-M

® membrane in this study was well justified. The 14-day experimental duration could compromise the integrity of the stratum corneum, leading to its degradation. Therefore, a stable synthetic membrane such as Strat-M

® was selected as the most appropriate alternative due to its structural and functional similarity to the human stratum corneum [

38,

39,

40].

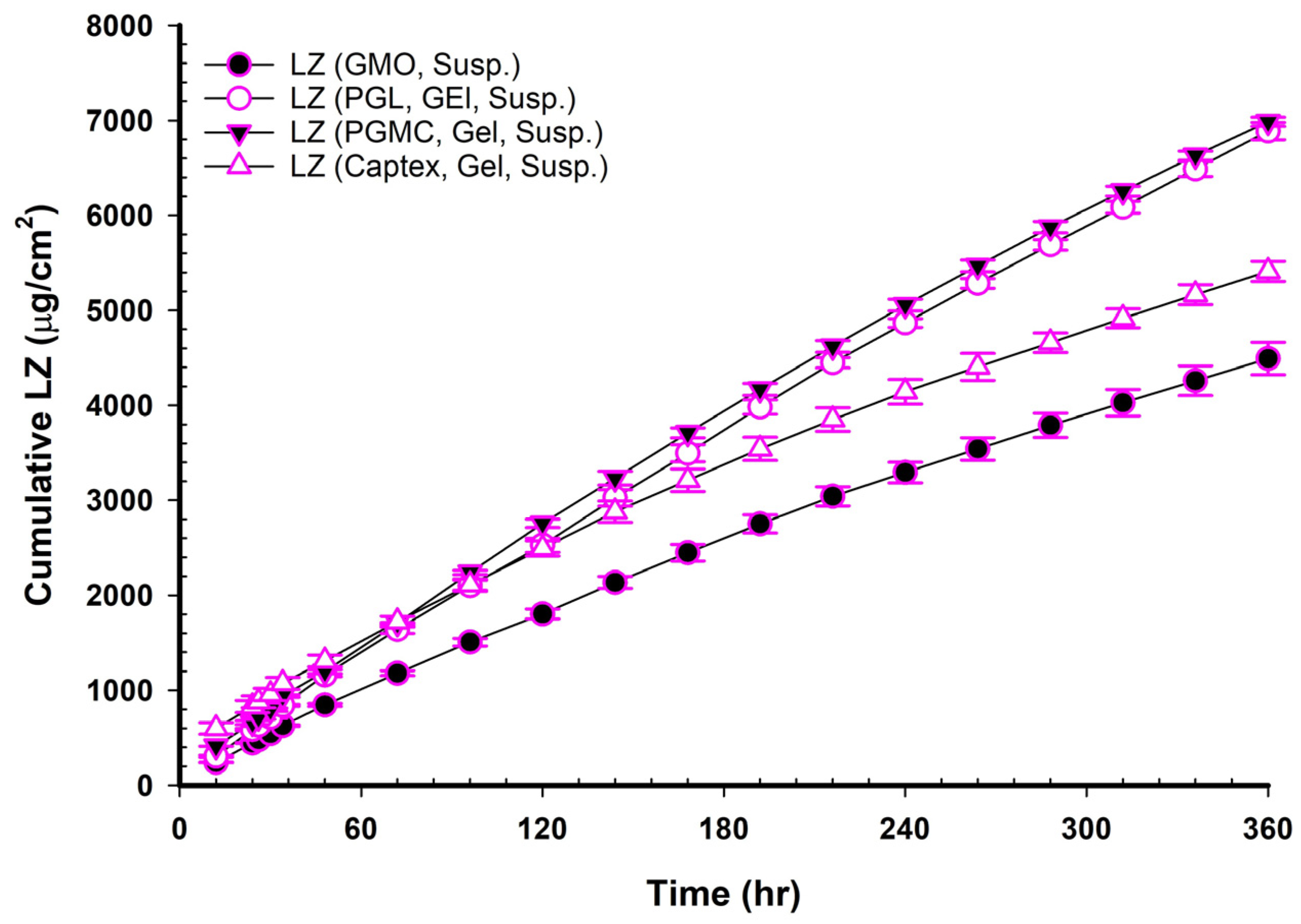

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the cumulative amounts of LZ (µg/cm

2) plotted versus time in hours for LZ suspensions in phosphate buffers with or without 20%

v/

v of TC, LZ NEMGs, and LZ gel suspensions. The calculated permeation parameters of LZ from all formulations are summarized in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7.

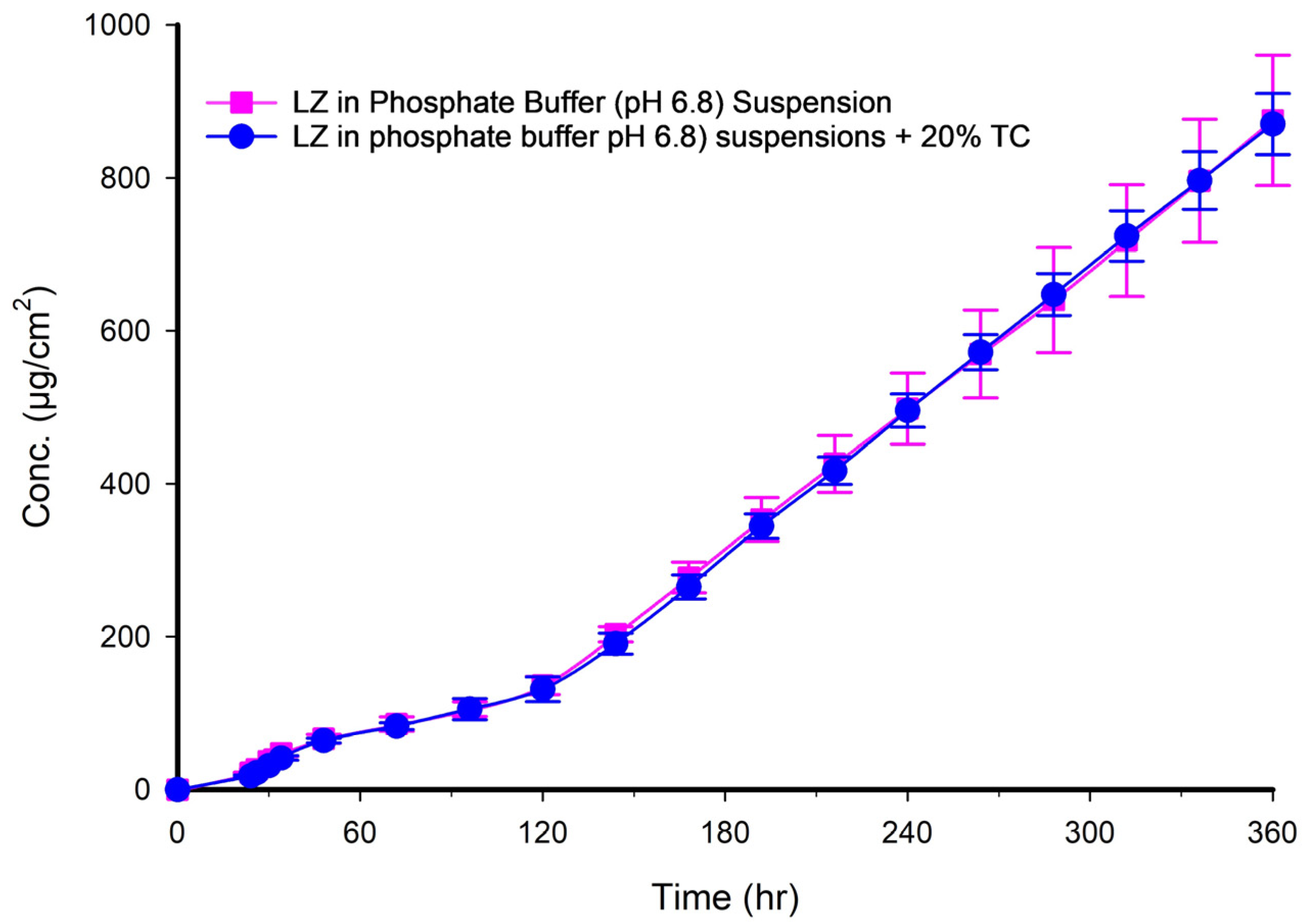

3.11. LZ Permeation from Phosphate Buffer Suspension

The ability of LZ to diffuse through the Strat-M

® membrane was examined both with and without 20%

v/

v TC suspended in phosphate buffer of pH 6.8. It was observed that LZ had very little permeation, and adding 20%

v/

v of TC had no discernible impact on permeation. Nearly identical permeability coefficients were also obtained.

Figure 4 and

Table 5, respectively, display LZ’s characteristics and in vitro permeation profiles in phosphate buffer with and without 20%

v/

v of TC.

3.12. LZ Permeation from NEMG Without GMO

In comparison to the LZ suspension in phosphate buffer, it was noted that a greater amount of LZ permeated from NEMG with no GMO. Consequently, the NEMG system facilitated enhanced drug permeation, as indicated by significantly higher flux, increased permeation coefficients, and reduced T

lag (

p < 0.05). This was further evidenced by an enhancement factor that was 16 times greater than that of the LZ suspensions in phosphate buffer, regardless of the presence of TC, as illustrated in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8. The enhanced permeation observed in the NEMG without GMO can be attributed to the nanostructure of the gel, which provides a significant surface area for membrane contact, thereby facilitating diffusion [

41]. Additionally, incorporating PG, TC, and Polysorbate 80 contributes to the enhancement of permeation, which will be elaborated upon in the following sections.

3.13. LZ Permeation from NEMG Containing GMO

Figure 5 and

Table 6 demonstrate that adding GMO to the NEMGs led to a significant increase in drug permeation and a decreased lag time compared to the NEMG without GMO (

p < 0.05). Previous studies reported that GMOs interacted with the skin’s stratum corneum to promote drug permeability. GMOs may increase penetration, especially when it comes to transdermal drug delivery [

42]. A disruption could aid drug diffusion in the stratum corneum’s lipid composition. Using cosolvents like PG and TC increases penetration when combined with GMOs. Such an effect was well investigated with either cosolvent alone or GMO [

42,

43,

44,

45].

3.14. LZ Permeation from NEMG Containing GMO and PE

Two main mechanisms explain the synergy between nanoemulsions and penetration enhancers: increased solubility and greater skin contact area, facilitating diffusion. The nano size of the nanoparticles allows them to penetrate skin pores effectively. Meanwhile, penetration enhancers such as surfactants, PG, TC, GMO, PGL, PGMC, and Captex

® work in conjunction with the nanoemulsion to disrupt the lipids in the stratum corneum, thereby increasing their fluidity and altering their structure. This disruption leads to voids and disorder within the lipid bilayers, further assisting drug entry into the skin’s deeper layers and systemic circulation [

41,

44,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. PGL, PGMC, and Captex were employed as PEs in various TDDS [

40,

52,

53]. The current investigation highlights the advantages of a nanoemulsion structure, including surfactants, cosolvents, and penetration enhancers, presenting a complex system that merits further exploration. Adding PGL, PGMC, or Captex

®, combined with GMO, significantly increased LZ permeation (

p < 0.05).

Figure 5 and

Table 6 demonstrate how these additional PEs enhanced the permeability of LZ when added to NEMG containing GMO in the following order: GMO/PGMC, NEMG > GMO/PGL, NEMG > GMO/Captex

®, NEMG > GMO, NEMG > NEMG without GMO. The permeability enhancement followed the following order: GMO/PGMC, NEMG > GMO/PGL, NEMG > GMO/Captex

®, NEMG > GMO, NEMG > NEMG without GMO, as shown in

Table 8. It was evident that the nanoemulsions and penetration enhancers function through distinct mechanisms that may interact to produce a synergistic effect, as already highlighted above. This assertion is backed by the high permeation coefficients and the permeation enhancement factor detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 8, which align with previously published data [

41,

46]. The NEMG of GMO/PGMC exhibited a significantly higher permeability coefficient than the others (

p < 0.05), which led to its selection for in vivo studies, and its gel suspension was also chosen.

3.15. Determination of the Permeation Lag Time

The diffusion process in TDDS commences in a non-steady state, illustrated by the initial segment of the curve, while the linear section represents steady-state diffusion. Fick’s second law provides a mathematical framework for describing the non-steady portion of the curve, whereas Fick’s first law offers an expression for the linear segment. The term “lag time” denotes the duration required to achieve a steady state, which can be determined by projecting the linear part of the permeation versus time curve onto the time axis. Due to a high initial penetration level of the LZ, the projection of the linear portion resulted in a negative value for the lag time. Consequently, several models were employed to analyze the diffusion profile segments following the initial segment of the curve and to determine the permeation lag time [

54]. The diffusion of LZ in the formulations closely aligned with the Higuchi model with lag time, as indicated by the highest coefficient value (R

2), which ranged from 0.99 to 0.9999 [

29]. The lag times, presented as mean ± standard deviation, for NEMGs and Emulgel suspensions were detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 7, respectively.

3.16. LZ Permeation from Emulgel Suspensions Containing GMO and PE

The LZ permeations from LZ Emulgel suspensions containing GMO and PEs were plotted in

Figure 6 and reported in

Table 7. The main findings indicated lower permeation rates, longer lag times, and lower PEF values than the corresponding NEMG (

Table 8 and

Table 9). In contrast to the LZ permeation profiles derived from NEMGs, the permeation profiles of the Emulgel suspension were characterized by a distinct steady state. Permeation enhancement through suspension may involve maintaining a drug concentration in the transdermal vehicle that surpasses its equilibrium solubility. This approach ensured a consistently higher thermodynamic activity, facilitating continuous drug diffusion across the membrane barrier and helping maintain the steady state [

51].

The flux of LZ from Emulgel suspensions was lower than that of NEMGs, with a significant difference (

p < 0.05). The ranking of the permeation coefficients is as follows: GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension or GMO/PGL Emulgel suspension > GMO/Captex

® Emulgel suspension > GMO Emulgel suspension (

p < 0.05). The reduction in both the flux and the permeation coefficients for the Emulgel suspension was attributed to its behavior as an emulgel rather than a nanoemulgel, which resulted in a loss of the advantages associated with the nanostructure of the emulsion. Because nanoemulgels have a much higher surface area for drug transfer and can more successfully contain penetration enhancers, their drug penetration in TDDS was often better than that of regular emulgels. These factors accelerated and enhanced drug penetration through the skin’s barriers and into the systemic circulation [

40]. The presence of nanostructure in the nanoemulgel could not be demonstrated in the suspension forms. However, this advantage was lost after 100 h of the experiment, as will be detailed later. NEMGs had flux comparable to Emulgel suspensions after 100 h of permeation. The result indicated that NEMGs changed to Emulgel suspension after 100 h, and the permeation rate decreased.

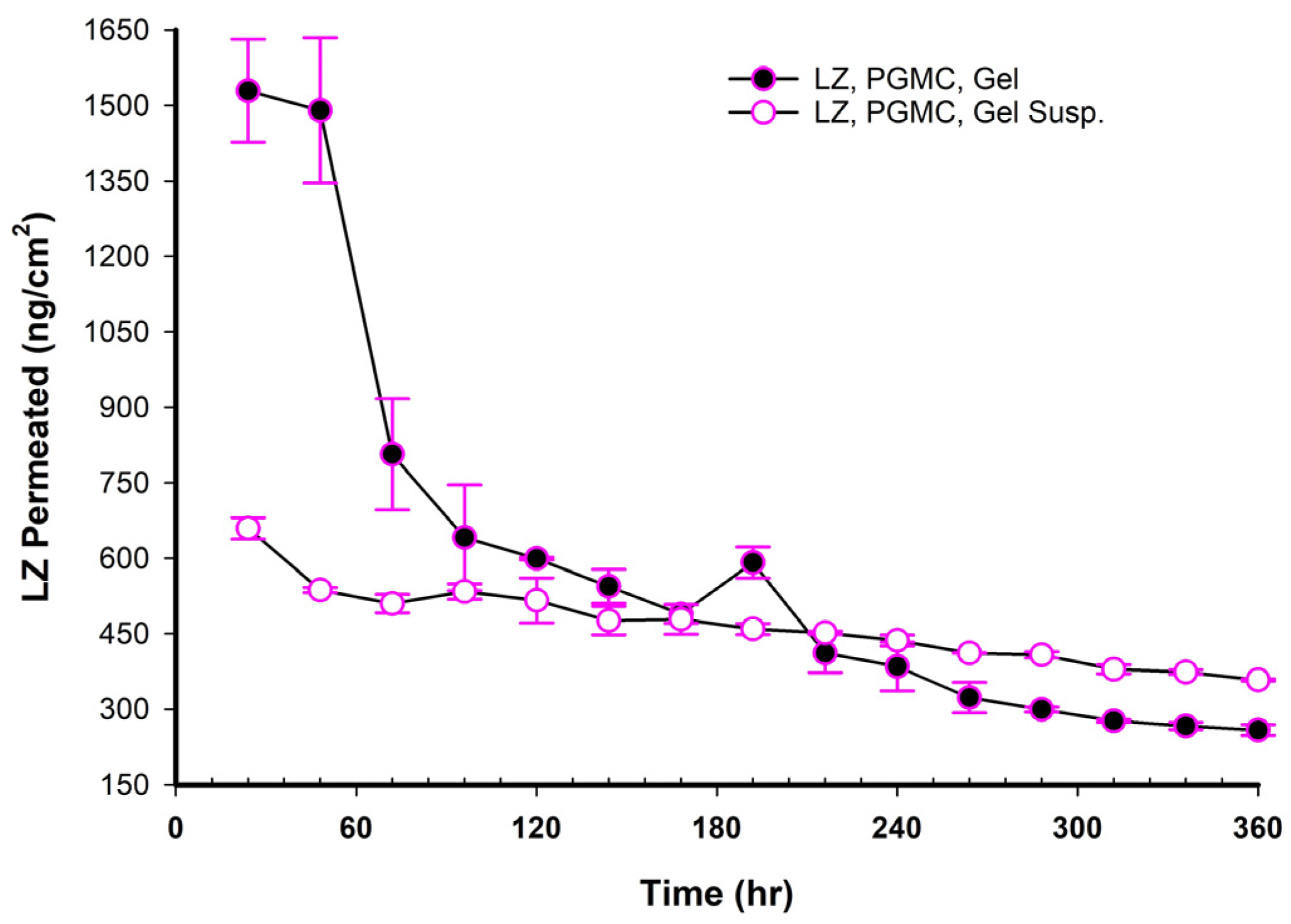

3.17. LZ Permeation/Day for 15 Days (ng/cm2 Versus Time in Hours)

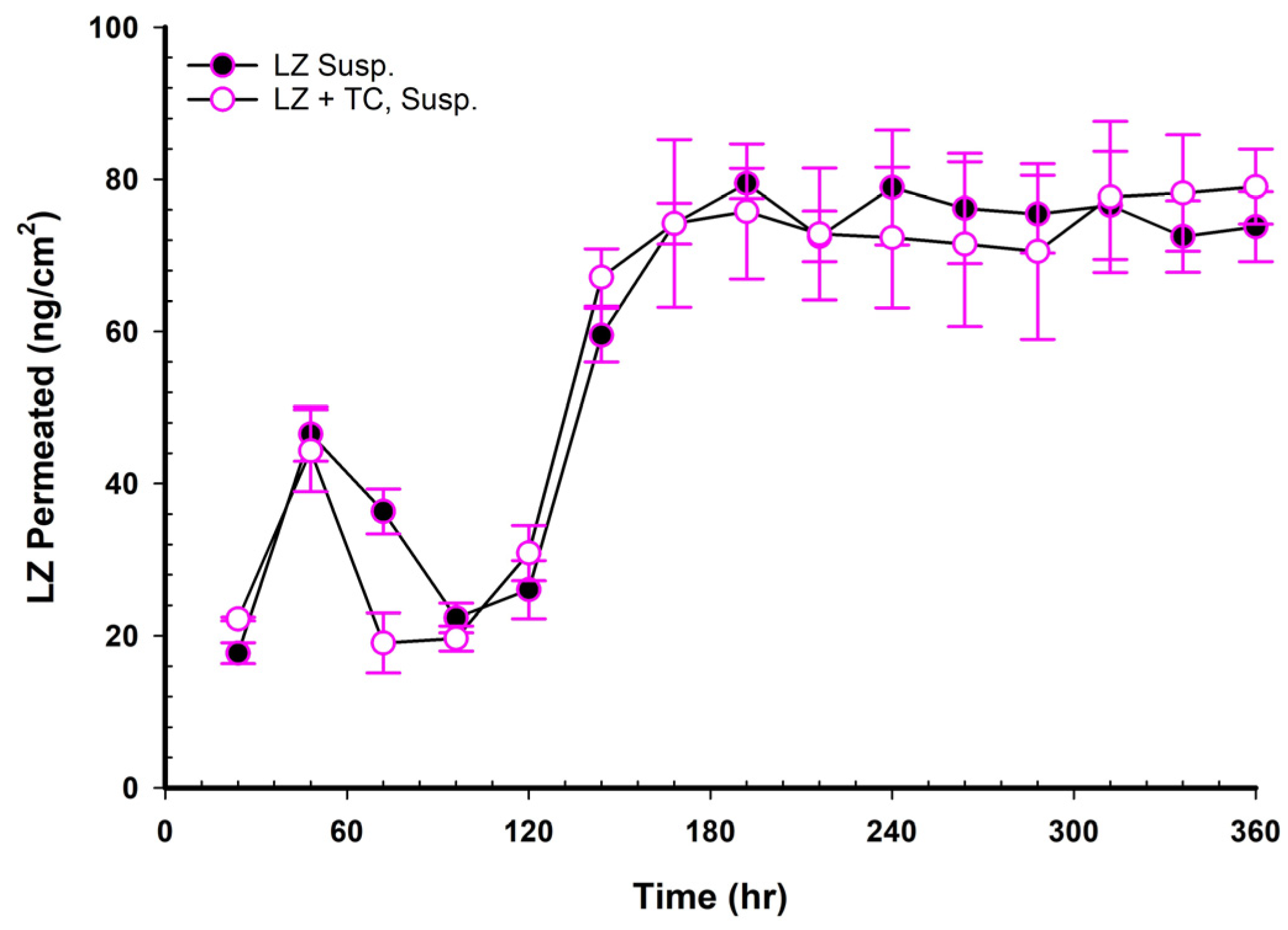

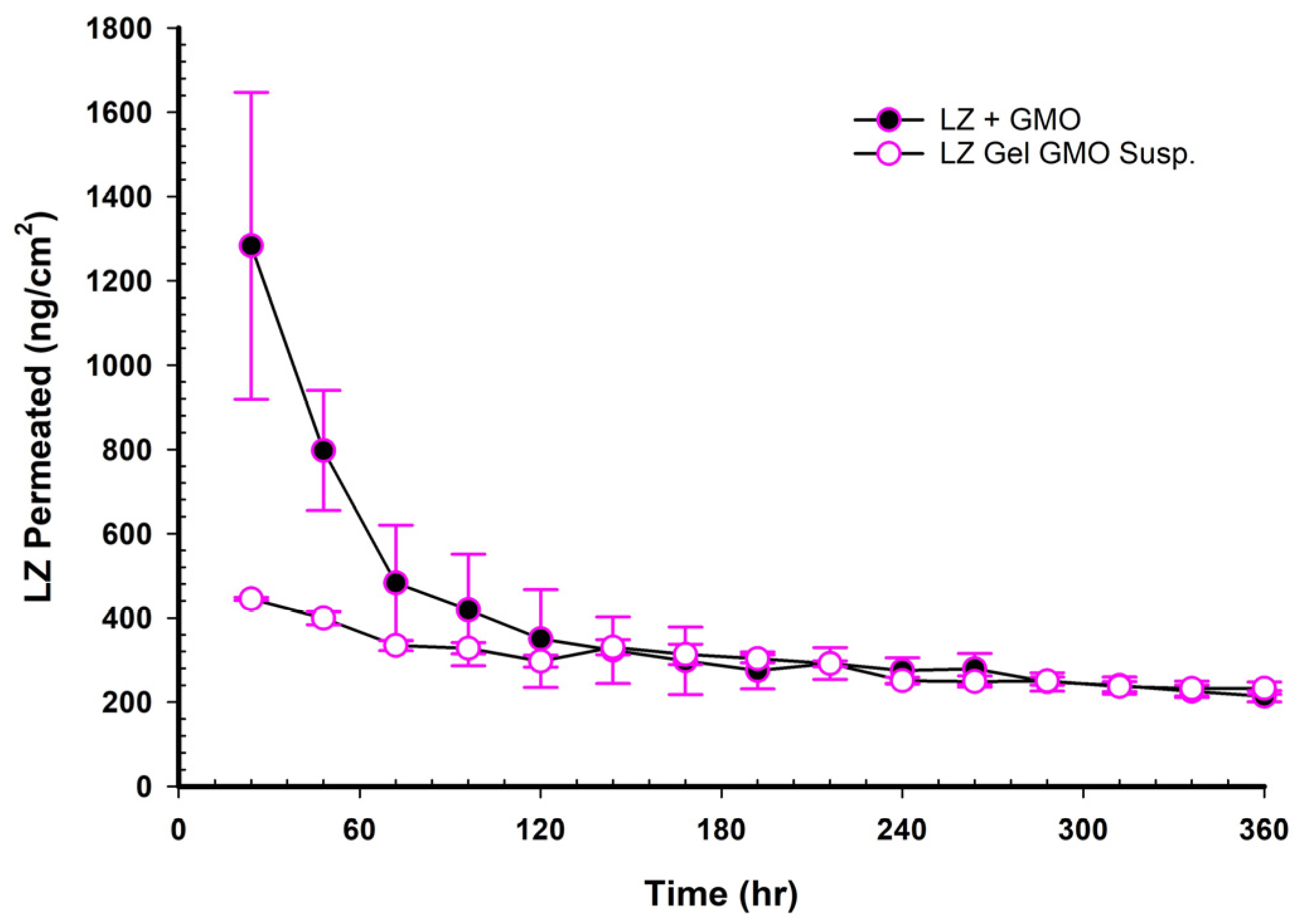

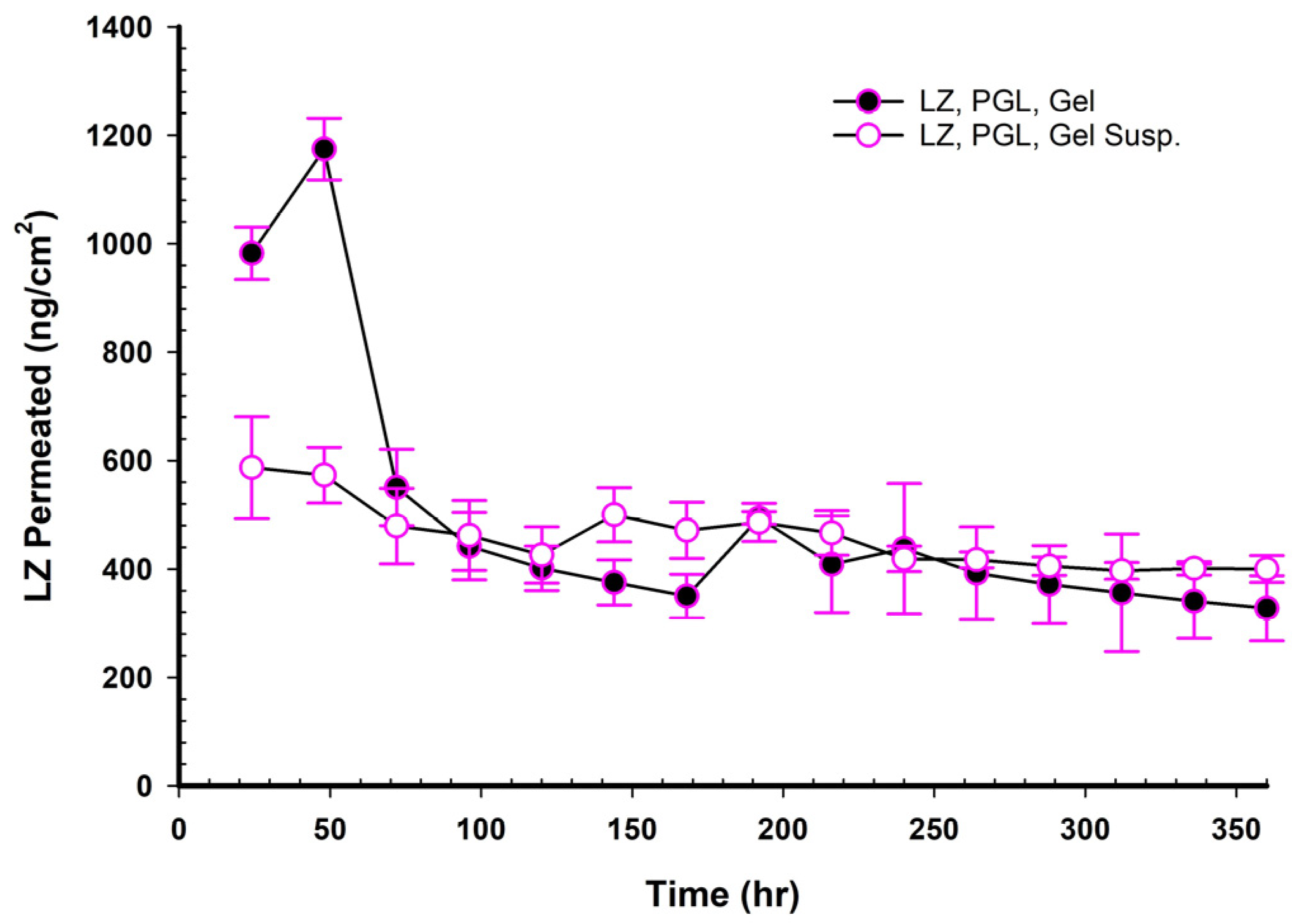

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrated the plots of the amount of LZ permeated per day versus time in hours over 15 days.

Figure 7 presents two profiles of LZ suspensions in phosphate buffer at pH 6.8, one with and one without 20% TC. The two profiles were nearly superimposed, indicating that the 20%

v/

v TC has no significant effect on the permeation of LZ from the suspension in phosphate-buffer solution. After 150 h, the amount of LZ permeated remained relatively constant up to 15 days (360 h). This observation implied that the quantity of LZ dissolved from the suspended solids in the suspension replaced the amount of LZ penetrated, maintaining the thermodynamic activity of the solution at a steady level.

When NEMGs and their counter-Emulgel suspensions were plotted against time over a 15-day timeframe, as shown in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, the amount of LZ permeated daily (24 h) by Emulgel suspensions was lower during the first 72 h than the amount permeated by NEMGs. After 100 h, the LZ penetration rates of Emulgel suspensions and NEMGs were almost equal, nearing a steady state. The components of NEMGs and Gel suspensions are shown in

Table 9.

Table 9 shows that gel suspensions and NEMGs have almost the same percentage

w/

w of NEMG base. In contrast to Emulgel suspensions, NEMGs exhibited greater initial permeation during 72 h, especially for GMO/NEMG and GMO/PGMC NEMGs. This period implied that NEMGs functioned as nanoemulgels and changed gradually into an Emulgel suspension. According to a microscopical examination, LZ started to crystallize out of the NEMGs samples. The slow solvent dragging of TC, PG, Polysorbate 80, and PE over the membrane towards the receptor medium may have been the direct cause of this transformation; however, more research is required to confirm this occurrence. After 100 h, the behavior of NEMGs was comparable to that of Emulgel suspensions, with a steep negative slope and a nearly constant LZ permeation rate. The diffusion was predominantly in suspensions for NEMGs and Emulgel suspensions.

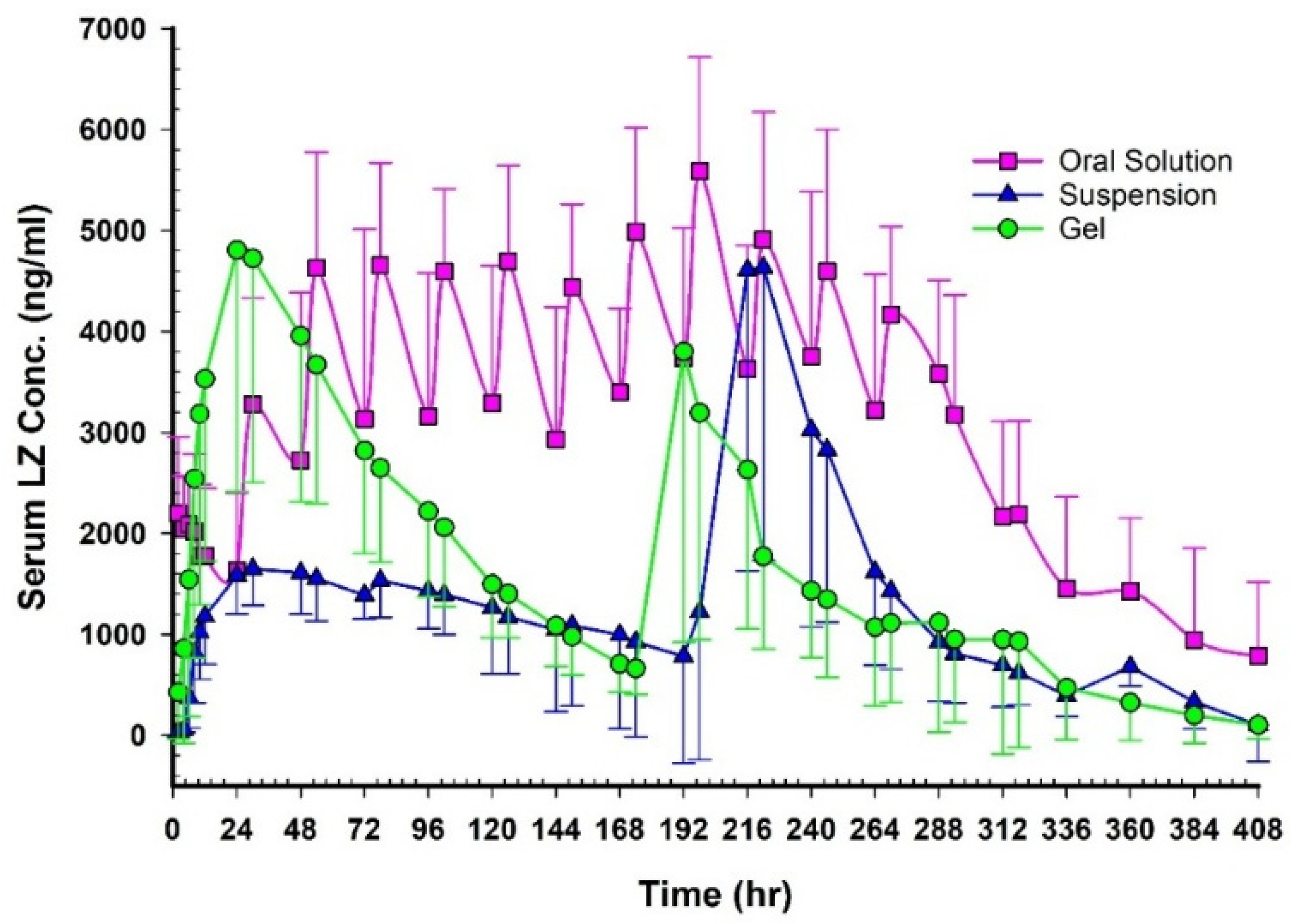

3.18. In Vivo PK Studies

HPLC Analysis & Validation

The 1–1000 ng/mL calibration curve showed a 0.9997 linear regression. The selectivity was checked as blank plasma was subjected to the extraction procedure, spiked with an internal standard, and did not show interfering peaks in the LZ retention time. It was due to the high selectivity of the fluorescence detector. According to the ICH Guideline M10 for bioanalytical method validation, the method’s sensitivity showed that the LOQ was 1 ng/mL and the LOD was 0.33 ng/mL. As previously reported [

30,

31], LZ’s average recovery was almost 100%, matching the published value of 96.94 ± 2.66%. This suggested that during extraction, a tiny amount was lost. Because they showed a higher in vitro permeation rate than other formulations, the nanoemulgel formulation and its suspension gel systems (PGMC and PGMC suspension) were chosen for in vivo PK studies.

Figure 12 shows plasma concentration–time profiles after oral, NEMG, and Emulgel administration.

Table 10 and

Table 11 summarize the key pharmacokinetic parameters. Following multiple oral administrations, the concentration-time profile of LZ at a dosage of 1 mg per day over 12 days revealed eleven absorption peaks. In contrast, double peaks were observed following transdermal applications using GMO/PGMC NEMG and GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension, indicating two distinct phases of permeation. The appearance of dual peaks in the plasma concentration profile may be attributed to time-dependent changes in the formulation. The initial peak likely corresponds to the diffusion of LZ from the freshly prepared formulation, which contained higher concentrations of cosolvents and penetration enhancers. As these components gradually migrated and their concentrations decreased within the formulation, LZ diffusion slowed, giving rise to the second plasma peak. This phenomenon was supported by the in vitro permeation studies (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11), where the first 100 h exhibited the highest daily LZ diffusion rates, closely aligning with the initial plasma concentration peak. The secondary peak may thus be linked to the subsequent reduction in LZ diffusion observed beyond 100 h, as depicted in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

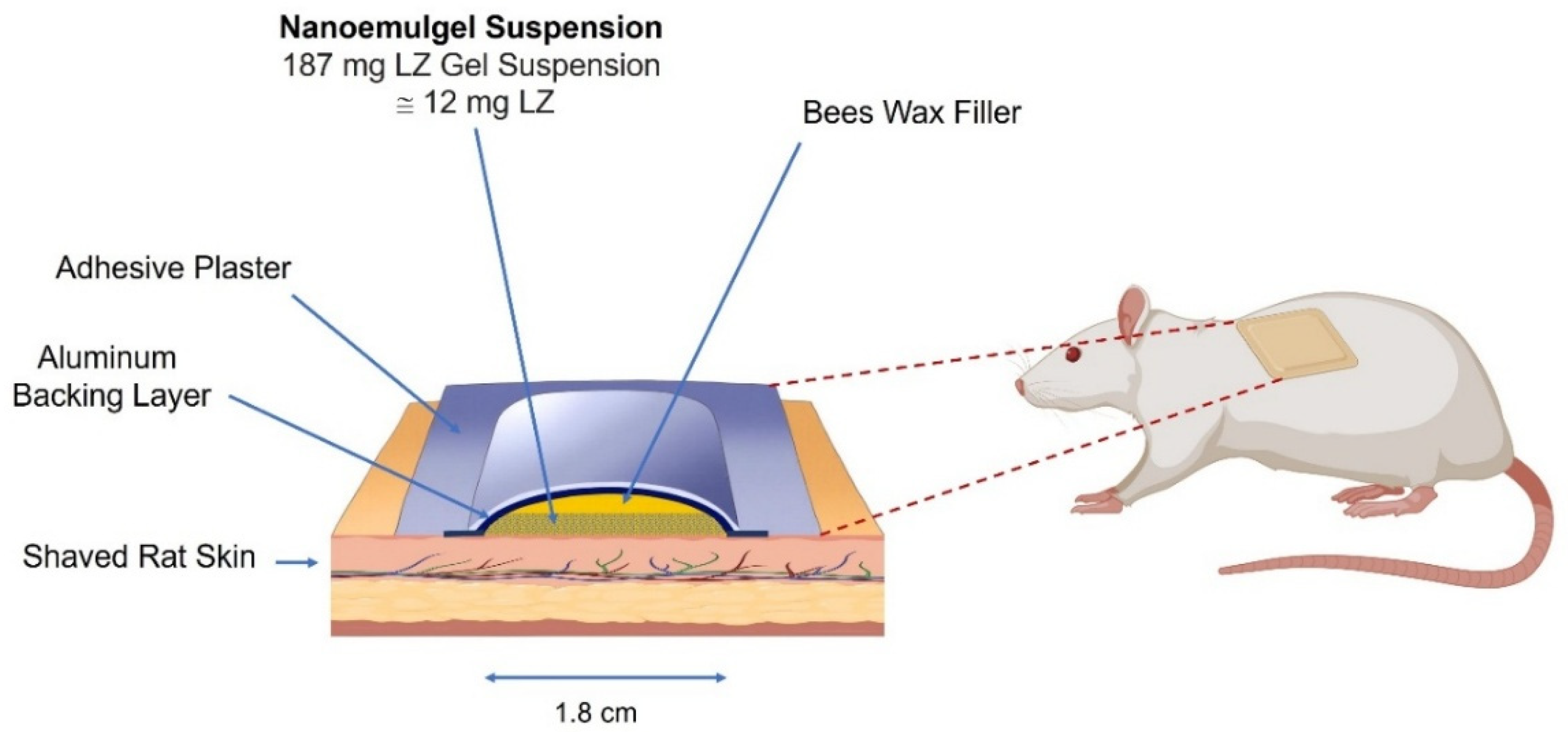

The relative bioavailability of LZ following transdermal application of the two patches, compared to oral solution administration, was approximately 57% for GMO/PGMC NEMG and 41% for GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension, as reported in

Table 11. The surface area of each patch measured 2.55 cm

2, which appeared insufficient to facilitate the complete permeation of LZ from NEMGs and gel suspension patches.

The oral solution exhibited a higher C

max and bioavailability than both gels; however, the AUC was only significant (

p < 0.05). This may be attributed to the fact that not all 12 mg of LZ could permeate from the topical gels, with a limited surface area of 2.55 cm

2. Over the initial 96 h, there were no significant differences in C

max and AUC between the oral solution and the GMO/PGMC NEMG (

p < 0.05). This finding indicated that the nanoemulgel structure permeated effectively, comparable to the oral solution of LZ in ethanol. As presented in

Table 11, the geometric mean ratio of LZ (at a 90% Confidence Interval (CI), GMO/PGMC NEMG) indicated a C

max comparable to that of the oral solution, measured at 0.89 (range: 0.7–1.12). The permeation surface area was recorded at 2.55 cm

2, which, if increased, could facilitate the attainment of bioequivalence.

Acknowledged skin permeability and drug metabolism differences between rats and humans should be carefully considered in transdermal drug delivery research, particularly during preclinical evaluation. While rat skin generally shows higher permeability and faster drug elimination than human skin, in vitro experiments can still provide reliable predictions of human skin permeability. Moreover, integrating pharmacokinetic parameters can improve the accuracy of interspecies comparisons [

55].

Furthermore, there were no discernible variations between the two emulgels regarding C

max and AUC (

p > 0.05). However, the C

max and AUC

0–174 for NEMGs were substantially greater than the equivalent AUC

0–174 for the Emulgel suspension (

p < 0.05), while the AUC

174–360 did not show a significant difference (

p > 0.05). As previously mentioned, the dominant nanoemulgel structure of GMO/PGMC NEMG is responsible for the first phase. The suspension gel dominated the permeation in the second phase for both emulgels, which led to no significant changes in the C

max and AUC of LZ (

p > 0.05). This observation is consistent with the in vitro permeation data for GMO/PGMC NEMG and GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension, as shown in

Figure 10.

3.19. Shelf-Life Stability of LZ Nanoemulgels

After almost 2 years of storage at room temperature, no significant physical and chemical changes were observed for any of the LZ/GMO/PGMC, NEMG, and LZ/GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension (Assay: 100.4 ± 2.23% for the first sample and 99.1 ± 1.60% for the second sample). Crystal growth was not observed.

Table 12 summarizes the stability data of LZ–PGMC NEMGs.

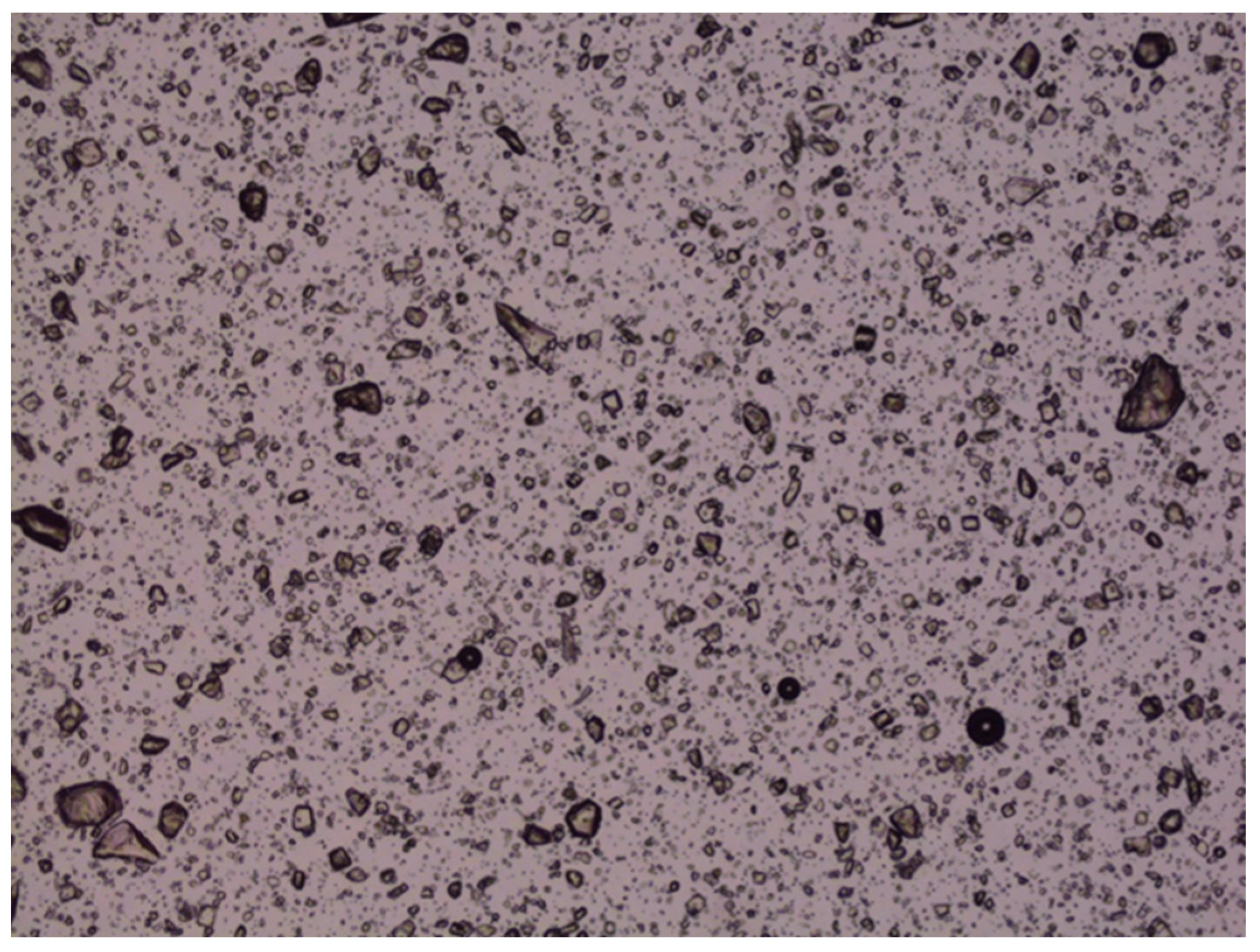

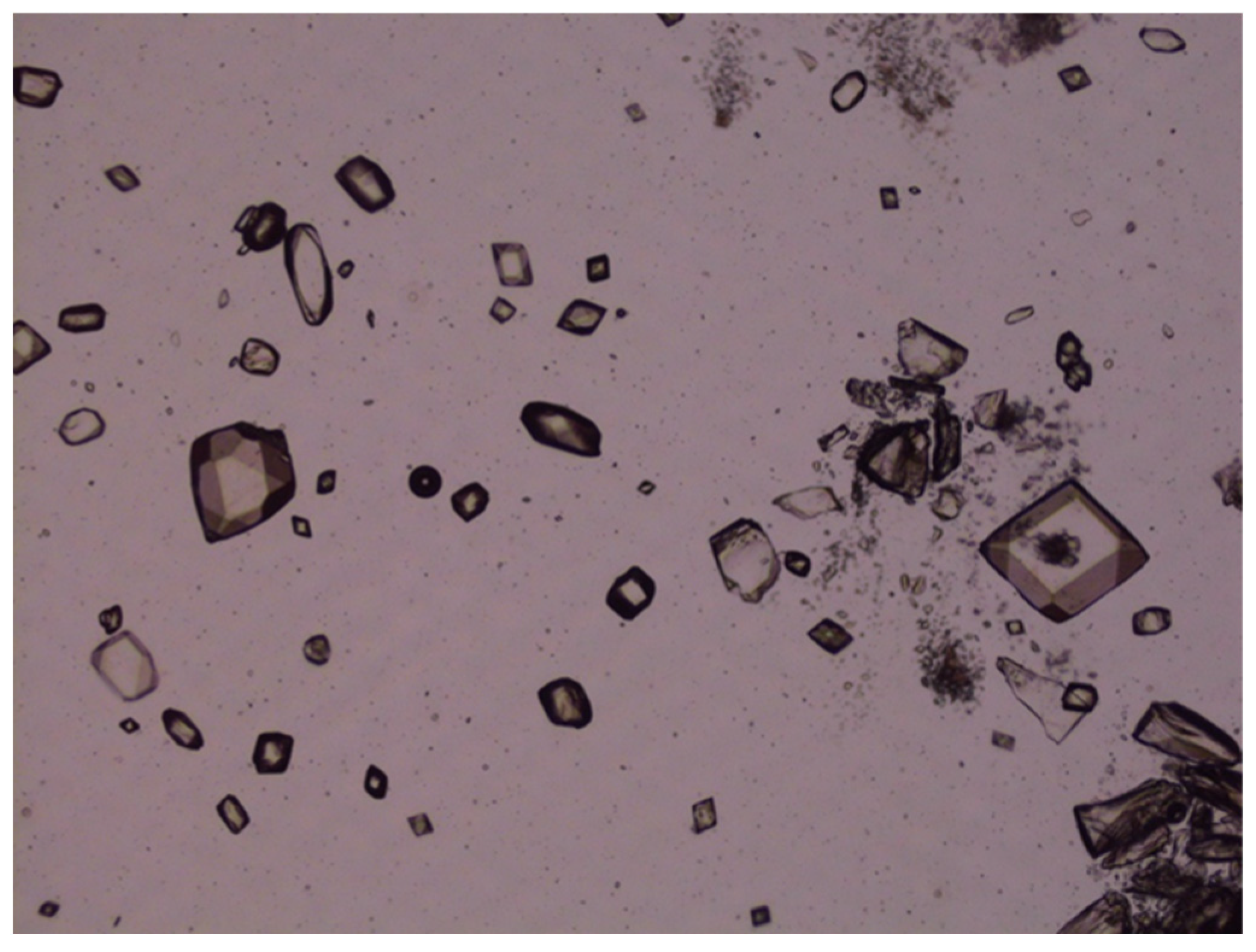

3.20. Accelerated Stability Studies of LZ Nanoemulgels and Emulgel Suspensions

The accelerated stability studies conducted at 50 °C over 40 days demonstrated that the chemical stability of various LZ nanoemulgels and emulgel suspensions, which included different penetration enhancers, was preserved (Assay: 100.6–102.4% with nearly 100% peak purity). However, crystal growth was noted in LZ emulgels that contained suspended particles of LZ, as illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. This occurrence was anticipated due to the presence of cosolvents and surfactants, which contributed to the thermodynamic instability of the emulgel suspensions at the elevated temperature of 50 °C.

In summary, the results of the preliminary stability investigations (both accelerated and shelf-life) indicated that LZ nanoemulgels and emulgel suspensions were expected to remain stable for a commendable period of two years. Nevertheless, further stability studies are necessary. These should include long-term assessments under varying temperature conditions (25 °C and 30 °C), humidity levels (60%, 65%, and 75% RH), and accelerated stability testing at 40 °C and 75% RH over six months.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and characterized non-aqueous LZ/NEMG formulations for transdermal drug delivery. The preparation process for the non-aqueous NEMGs was straightforward, and the formation of the NEMG occurred spontaneously, resulting in a clear, thick gel. The optimized GMO/PGMC-based NEMG exhibited superior permeation, a biphasic pharmacokinetic behavior, and a good stability profile. In vivo evaluations demonstrated sustained plasma concentrations and a bioavailability of 57% relative to the oral solution for the 2.55 cm2 patch. This suggested that transdermal nanoemulgels could be a clinically viable alternative to oral administration by increasing the surface area. The LZ/GMO/PGMC Emulgel suspension, conversely, demonstrated reduced permeability and lower relative bioavailability due to the loss of the emulgel’s nanostructure, an essential factor in enhancing the permeation of LZ.

By facilitating controlled releases, minimizing systemic side effects, and improving patient adherence, LZ nanoemulgels showed considerable promise for enhancing therapeutic outcomes in breast cancer management. Future research should concentrate on scaling production, assessing long-term stability under ICH guidelines, and conducting clinical evaluations in humans to ascertain their translational potential.