Investigating Hybrid PLGA-Lipid Nanoparticles as an Innovative Delivery Tool for Palmitoylethanolamide to Muscle Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Hybrid Lipid-PLGA Nanoparticle Preparation

2.3. Particle Size, Surface Charge, and Morphology Analysis

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.5. Quantification of PEA by HPLC

2.6. Determination of Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Loading

2.7. Stability Study

2.8. In Vitro PEA Release

2.9. Physical State Characterization of PEA

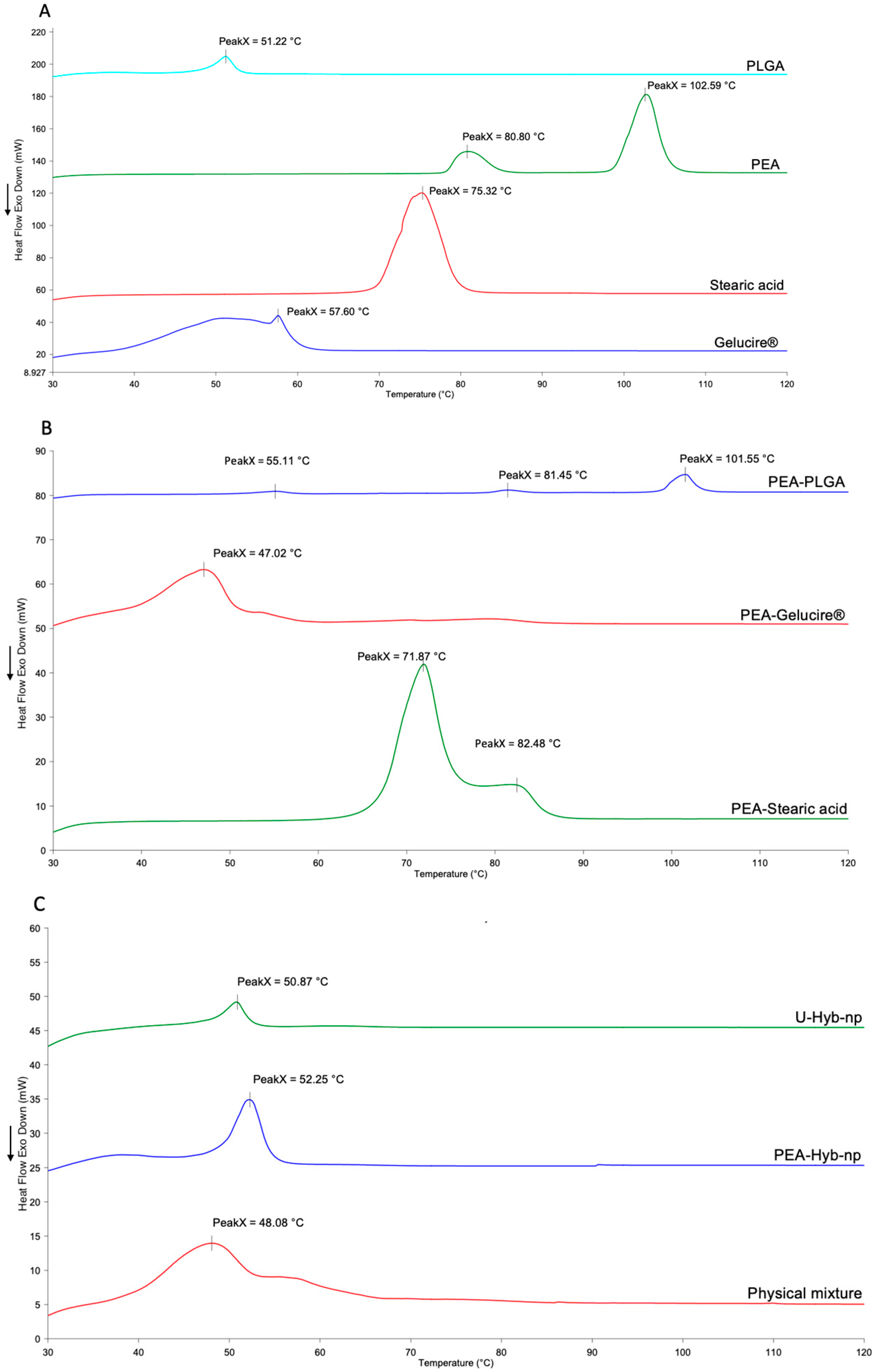

2.9.1. DSC Analysis

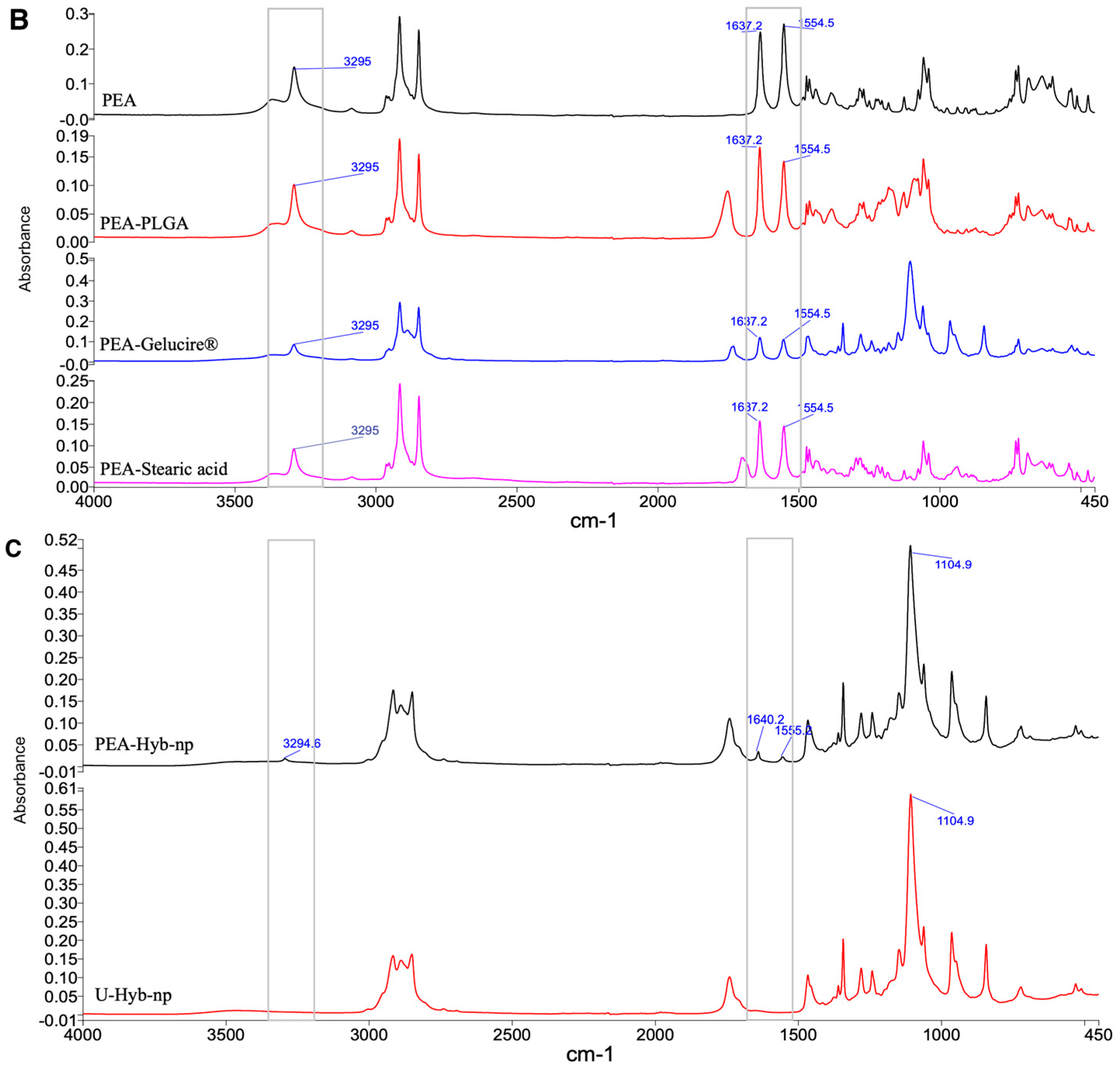

2.9.2. FT-IR Analysis

2.9.3. XRD Scanning Analysis

2.10. In Vitro Cell Analyses: Cell Culture

2.11. Cytotoxicity Test

2.12. Cellular Uptake of Coumarin-6-Labeled Nanoparticles by Flow Cytometric Analysis

2.13. Confocal Microscopy Analysis

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nanoparticle Formulation and Characterization

3.2. Characterization of the Optimized PEA-Hyb-np

3.2.1. Morphology Study

3.2.2. Stability Assessment

3.2.3. In Vitro PEA Release from Hybrid Nanoparticles

3.2.4. Thermal Analysis

3.2.5. FT-IR

3.2.6. XRD Scanning Analysis

3.3. In Vitro Cell Analyses

3.3.1. Cytotoxicity Assessment

3.3.2. Cellular Uptake

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DL | Drug Loading |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| EE | Encapsulation Efficiency |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| GRAS | Generally regarded as safe |

| HAADF | High-angle annular dark-field |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| MTT | Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| P/S | Penicillin–streptomycin |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| PEA | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| PEA-Hyb-np | PEA-loaded hybrid nanoparticles |

| PEA-PLGA-np | PEA-loaded PLGA nanoparticle |

| PEA/Gel-PLGA-np | PEA/Gelucire-loaded PLGA nanoparticle |

| PEA/Ste-PLGA-np | PEA/Stearic acid-loaded PLGA nanoparticle |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PPAR-α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| U-Hyb-np | Unloaded hybrid nanoparticles |

References

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Fusco, M.; Della Valle, M.F.; Zusso, M.; Costa, B.; Giusti, P. Palmitoylethanolamide, a Naturally Occurring Disease-Modifying Agent in Neuropathic Pain. Inflammopharmacology 2014, 22, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S.; Di Marzo, V. The Pharmacology of Palmitoylethanolamide and First Data on the Therapeutic Efficacy of Some of Its New Formulations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1349–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, L.; Mattsson, S.; Fowler, C.J. Palmitoylethanolamide for the Treatment of Pain: Pharmacokinetics, Safety and Efficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, V.; Steardo, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Monaco, F.; Steardo, L. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Multifunctional Molecule for Neuroprotection, Chronic Pain, and Immune Modulation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huschtscha, Z.; Silver, J.; Gerhardy, M.; Urwin, C.S.; Kenney, N.; Le, V.H.; Fyfe, J.J.; Feros, S.A.; Betik, A.C.; Shaw, C.S.; et al. The Effect of Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) on Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy, Strength, and Power in Response to Resistance Training in Healthy Active Adults: A Double-Blind Randomized Control Trial. Sports Med. Open 2024, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S.; Maretti, E.; Battini, R.; Leo, E. Linking Endocannabinoid System, Palmitoylethanolamide and Sarcopenia in View of Therapeutic Outcomes. In Cannabis, Cannabinoids and Endocannabinoids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maretti, E.; Molinari, S.; Battini, R.; Rustichelli, C.; Truzzi, E.; Iannuccelli, V.; Leo, E. Design, Characterization, and In Vitro Assays on Muscle Cells of Endocannabinoid-like Molecule Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles for a Therapeutic Anti-Inflammatory Approach to Sarcopenia. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R. ALIAmides Update: Palmitoylethanolamide and Its Formulations on Management of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattace Raso, G.; Russo, R.; Calignano, A.; Meli, R. Palmitoylethanolamide in CNS Health and Disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 86, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danhier, F.; Ansorena, E.; Silva, J.M.; Coco, R.; Le Breton, A.; Préat, V. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles: An Overview of Biomedical Applications. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabar, G.M.; Mahajan, K.D.; Calhoun, M.A.; Duong, A.D.; Souva, M.S.; Xu, J.; Czeisler, C.; Puduvalli, V.K.; Otero, J.J.; Wyslouzil, B.E.; et al. Micelle-Templated, Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles for Hydrophobic Drug Delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagreca, E.; Onesto, V.; Di Natale, C.; La Manna, S.; Netti, P.A.; Vecchione, R. Recent Advances in the Formulation of PLGA Microparticles for Controlled Drug Delivery. Prog. Biomater. 2020, 9, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chan, J.M.; Gu, F.X.; Rhee, J.-W.; Wang, A.Z.; Radovic-Moreno, A.F.; Alexis, F.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C. Self-Assembled Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles: A Robust Drug Delivery Platform. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 1696–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitman, J.; Biru, E.I.; Stan, R.; Iovu, H. Review of Hybrid PLGA Nanoparticles: Future of Smart Drug Delivery and Theranostics Medicine. Mater. Des. 2020, 193, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Almazán, J.P.; Castro-Ceseña, A.B.; Aguila, S.A. Evaluation of the Release Kinetics of Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Compounds from Lipid–Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 15801–15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pridgen, E.M.; Alexis, F.; Kuo, T.T.; Levy-Nissenbaum, E.; Karnik, R.; Blumberg, R.S.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C. Transepithelial Transport of Fc-Targeted Nanoparticles by the Neonatal Fc Receptor for Oral Delivery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 213ra167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafique, M.; Ur Rehman, M.; Kamal, Z.; Alzhrani, R.M.; Alshehri, S.; Alamri, A.H.; Bakkari, M.A.; Sabei, F.Y.; Safhi, A.Y.; Mohammed, A.M.; et al. Formulation Development of Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles of Doxorubicin and Its In-Vitro, in-Vivo and Computational Evaluation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1025013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, D.; Saxel, O. Serial Passaging and Differentiation of Myogenic Cells Isolated from Dystrophic Mouse Muscle. Nature 1977, 270, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.; Ahmed, N.; Rehman, A.U. Recent Applications of PLGA Based Nanostructures in Drug Delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 159, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, A.A.; Vador, N.; Jagtap, A.; Nagarsenker, M.S. Lipid Nanocarriers (GeluPearl) Containing Amphiphilic Lipid Gelucire 50/13 as a Novel Stabilizer: Fabrication, Characterization and Evaluation for Oral Drug Delivery. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 275102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubray, O.; Jannin, V.; Demarne, F.; Pellequer, Y.; Lamprecht, A.; Béduneau, A. In-Vitro Investigation Regarding the Effects of Gelucire® 44/14 and Labrasol® ALF on the Secretory Intestinal Transport of P-Gp Substrates. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 515, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristroph, K.; Prud’homme, R. Hydrophobic Ion Pairing: Encapsulating Small Molecules, Peptides, and Proteins into Nanocarriers. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 4207–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Qin, M.; Ye, G.; Gong, H.; Li, M.; Sui, X.; Liu, B.; Fu, Q.; He, Z. Hydrophobic Ion Pairing-Based Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems: A New Strategy for Improving the Therapeutic Efficacy of Water-Soluble Drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2023, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Goulart, G.C.A.; Ferreira, L.A.M.; Carneiro, G. Hydrophobic Ion Pairing as a Strategy to Improve Drug Encapsulation into Lipid Nanocarriers for the Cancer Treatment. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghrebi, S.; Jambhrunkar, M.; Joyce, P.; Prestidge, C.A. Engineering PLGA–Lipid Hybrid Microparticles for Enhanced Macrophage Uptake. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 4159–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgoustakis, K. Pegylated Poly(Lactide) and Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles: Preparation, Properties and Possible Applications in Drug Delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2004, 1, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, D.; Bruschetta, G.; Cordaro, M.; Crupi, R.; Siracusa, R.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Micronized/Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide Displays Superior Oral Efficacy Compared to Nonmicronized Palmitoylethanolamide in a Rat Model of Inflammatory Pain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2014, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehkri, S.; Dinesh, K.G.; Ashok, G.; Bopanna, K. Pharmacokinetics of Micronized and Water Dispersible Palmitoylethanolamide in Comparison with Standard Palmitoylethanolamide Following Single Oral Administration in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Indian. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 57, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskey, D.; Mallard, A.R.; Rao, A. Increased Absorption of Palmitoylethanolamide Using a Novel Dispersion Technology System (LipiSperse®). J. Nutraceuticals Food Sci. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, B.C.; Zografi, G. Characteristics and Significance of the Amorphous State in Pharmaceutical Systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Amorphous Pharmaceutical Solids: Preparation, Characterization and Stabilization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 48, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, E.R.; Suhendra, D.; NuansaWindari, B.A.; Kurniawati, L. Enzymatic Synthesis of Palmitoylethanolamide from Ketapang Kernel Oil. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1321, 022034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, V.; Carton, F.; Vattemi, G.; Arpicco, S.; Stella, B.; Berlier, G.; Marengo, A.; Boschi, F.; Malatesta, M. Uptake and Intracellular Distribution of Different Types of Nanoparticles in Primary Human Myoblasts and Myotubes. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 560, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roointan, A.; Kinpour, S.; Memari, F.; Gandomani, M.; Gheibi Hayat, S.M.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid): The Most Ardent and Flexible Candidate in Biomedicine! Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater 2018, 67, 1028–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, I.; Battaglia, G. Endocytosis at the Nanoscale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2718–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Organic Phase (in 3 mL of DCM) | Aqueous Phase (10 mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stearic Acid (mg) | Gelucire (mg) | PLGA (mg) | PEA (mg) | Span85 (mg) | Pluronic F68 (%, w/v) | |

| PEA-PLGA-np | - | - | 80 | 10 | 120 | 0.8 |

| PEA/Ste-PLGA-np | 10 | - | 80 | 10 | 120 | 0.8 |

| PEA/Gel-PLGA-np | - | 80 | 80 | 10 | 120 | 0.8 |

| PEA-Hyb-np | 10 | 80 | 80 | 10 | 120 | 0.8 |

| U-Hyb-np | 10 | 80 | 80 | - | 120 | 0.8 |

| Sample | Size (nm ± SD) | PDI (± SD) | Z-Potential (mV ± SD) | EE (% ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA-PLGA-np | 386 ± 15 | 0.384 ± 0.043 | −20.6 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 0.2 |

| PEA/Ste-PLGA-np | 128 ± 8 | 0.238 ± 0.010 | −33.9 ± 0.4 | 31.3 ± 1.6 |

| PEA/Gel-PLGA-np | 183 ± 30 | 0.280 ± 0.019 | −25.3 ± 1.3 | 56.8 ± 0.7 |

| PEA-Hyb-np | 146 ± 7 | 0.268 ± 0.051 | −29.6 ± 0.8 | 79.1 ± 0.1 |

| U-Hyb-np | 167 ± 6 | 0.324 ± 0.113 | −30.7 ± 0.8 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maretti, E.; Molinari, S.; Partel, S.; Recchia, B.; Rustichelli, C.; Leo, E. Investigating Hybrid PLGA-Lipid Nanoparticles as an Innovative Delivery Tool for Palmitoylethanolamide to Muscle Cells. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111412

Maretti E, Molinari S, Partel S, Recchia B, Rustichelli C, Leo E. Investigating Hybrid PLGA-Lipid Nanoparticles as an Innovative Delivery Tool for Palmitoylethanolamide to Muscle Cells. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111412

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaretti, Eleonora, Susanna Molinari, Sonia Partel, Beatrice Recchia, Cecilia Rustichelli, and Eliana Leo. 2025. "Investigating Hybrid PLGA-Lipid Nanoparticles as an Innovative Delivery Tool for Palmitoylethanolamide to Muscle Cells" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111412

APA StyleMaretti, E., Molinari, S., Partel, S., Recchia, B., Rustichelli, C., & Leo, E. (2025). Investigating Hybrid PLGA-Lipid Nanoparticles as an Innovative Delivery Tool for Palmitoylethanolamide to Muscle Cells. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111412