Fused Membrane-Targeted Nanoscale Gene Delivery System Based on an Asymmetric Membrane Structure for Ischemic Stroke

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Extraction and Characterization of EXOs

2.3. Establishment of a Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) Model

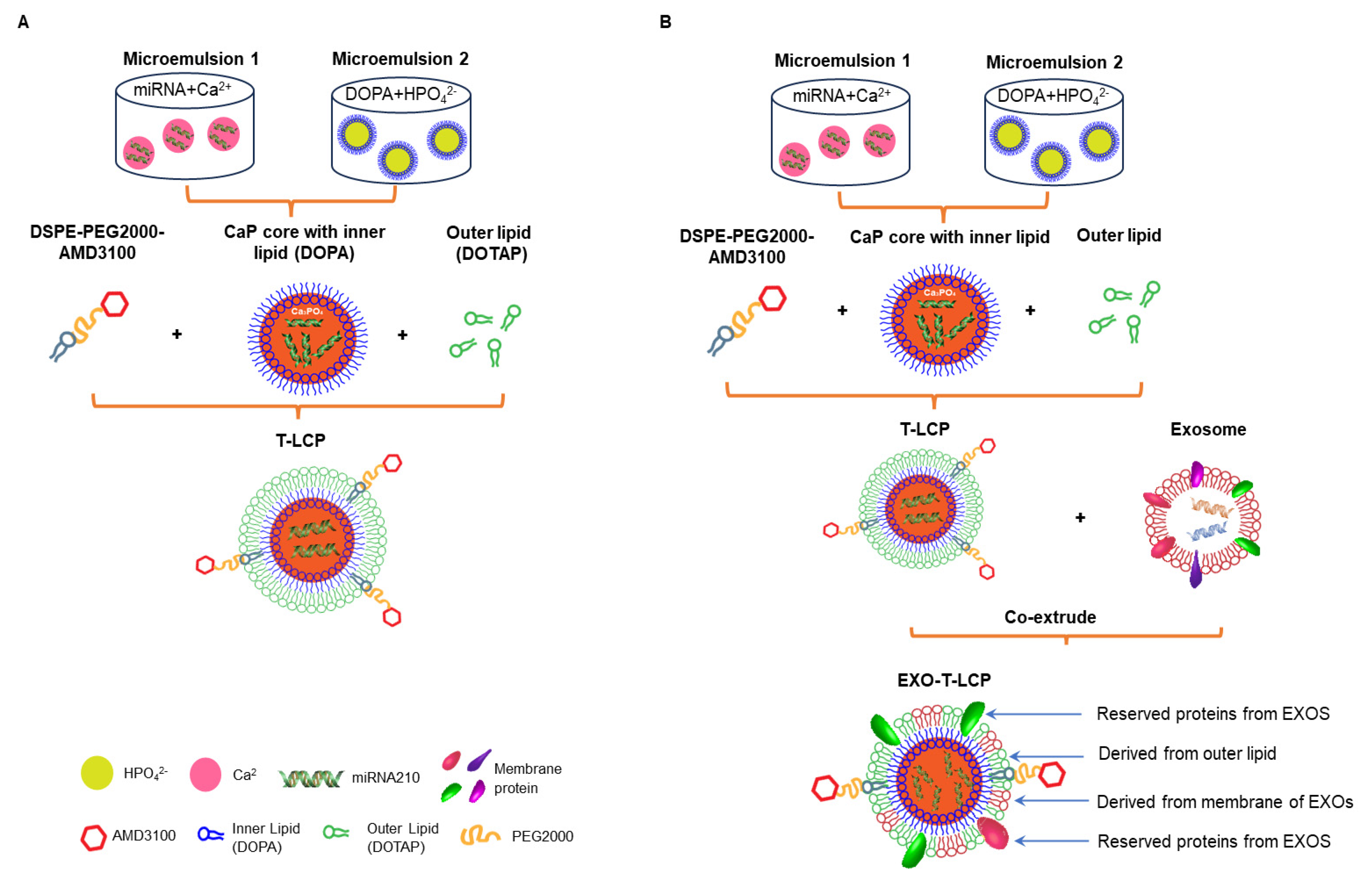

2.4. Preparation of LCP/T-LCP

2.5. Preparation of Fused Membrane Formulations and Determination of the Optimal Fusion Ratio

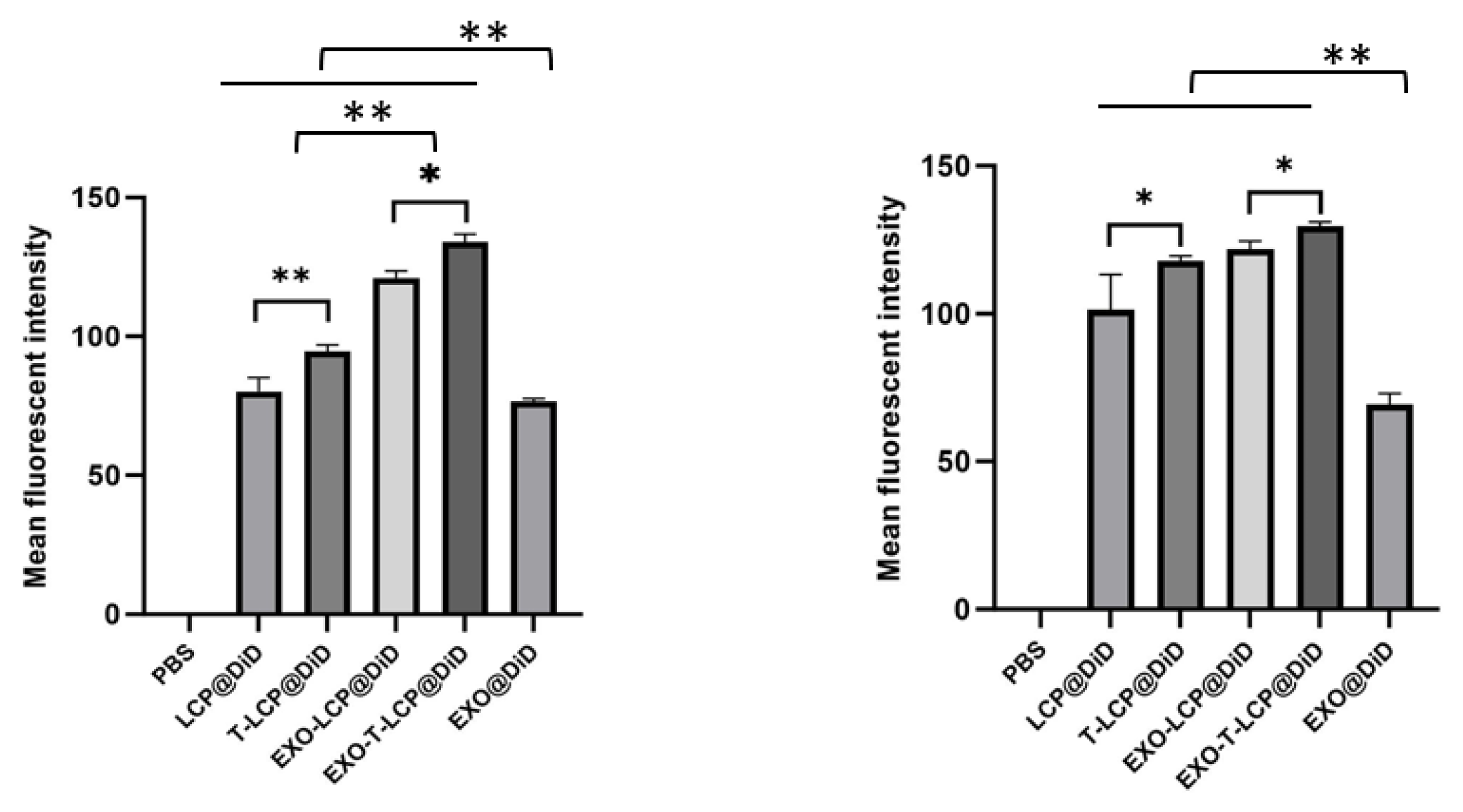

2.6. Uptake of Different Formulations in Two Types of Cells

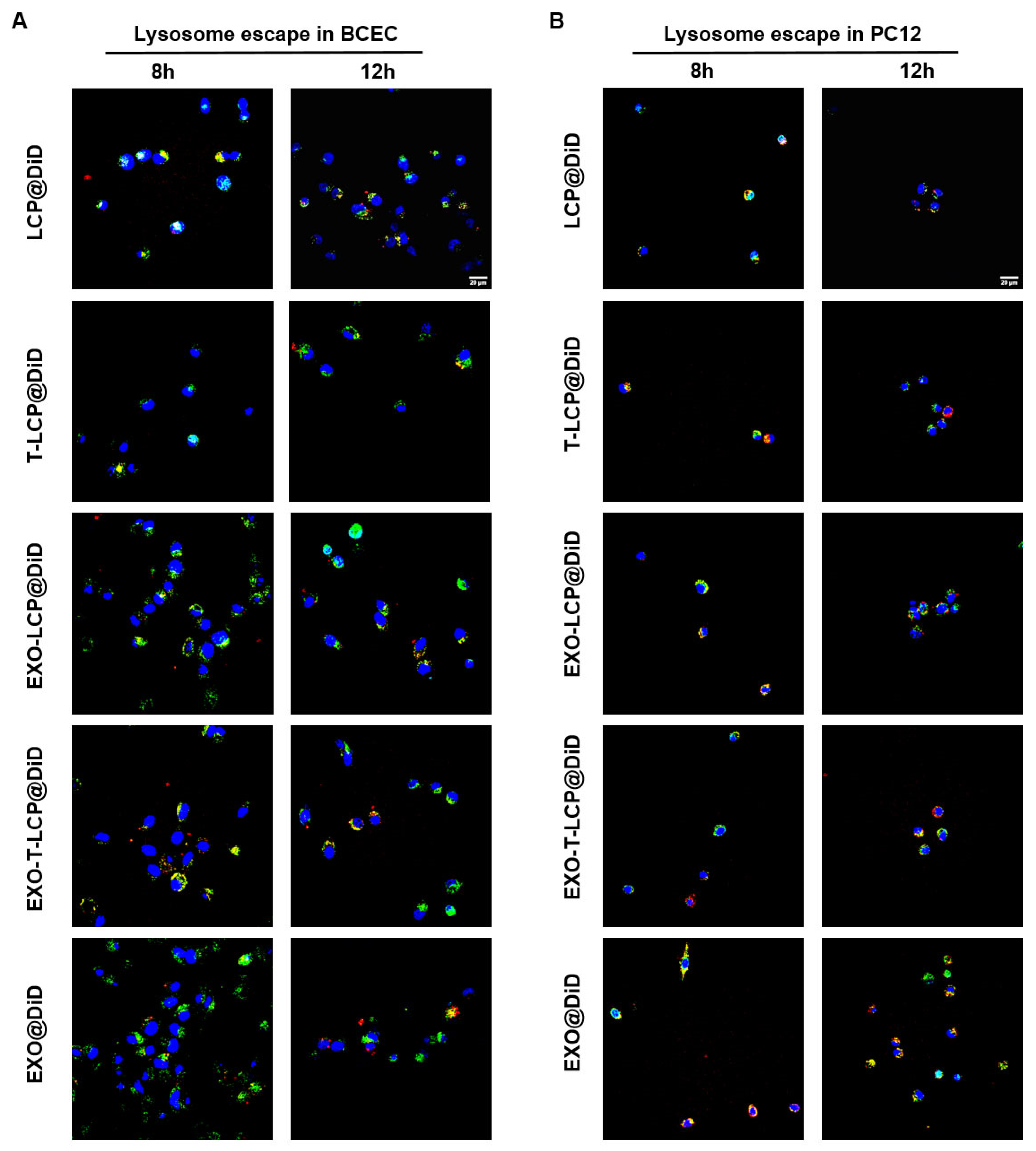

2.7. Lysosomal Escape of Different Formulations in Two Cell Types

2.8. Transfection Efficiency of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)-Loaded Formulations in Different Cells

2.9. Protective Effects of miRNA-210-Loaded Formulations Against Mitochondrial Damage in Different Cells

2.10. Assessment of the In Vivo Targeting of Different Formulations

2.11. Pharmacodynamic Assessment of EXO-LCP-Fused Membrane Formulations

3. Results and Discussion

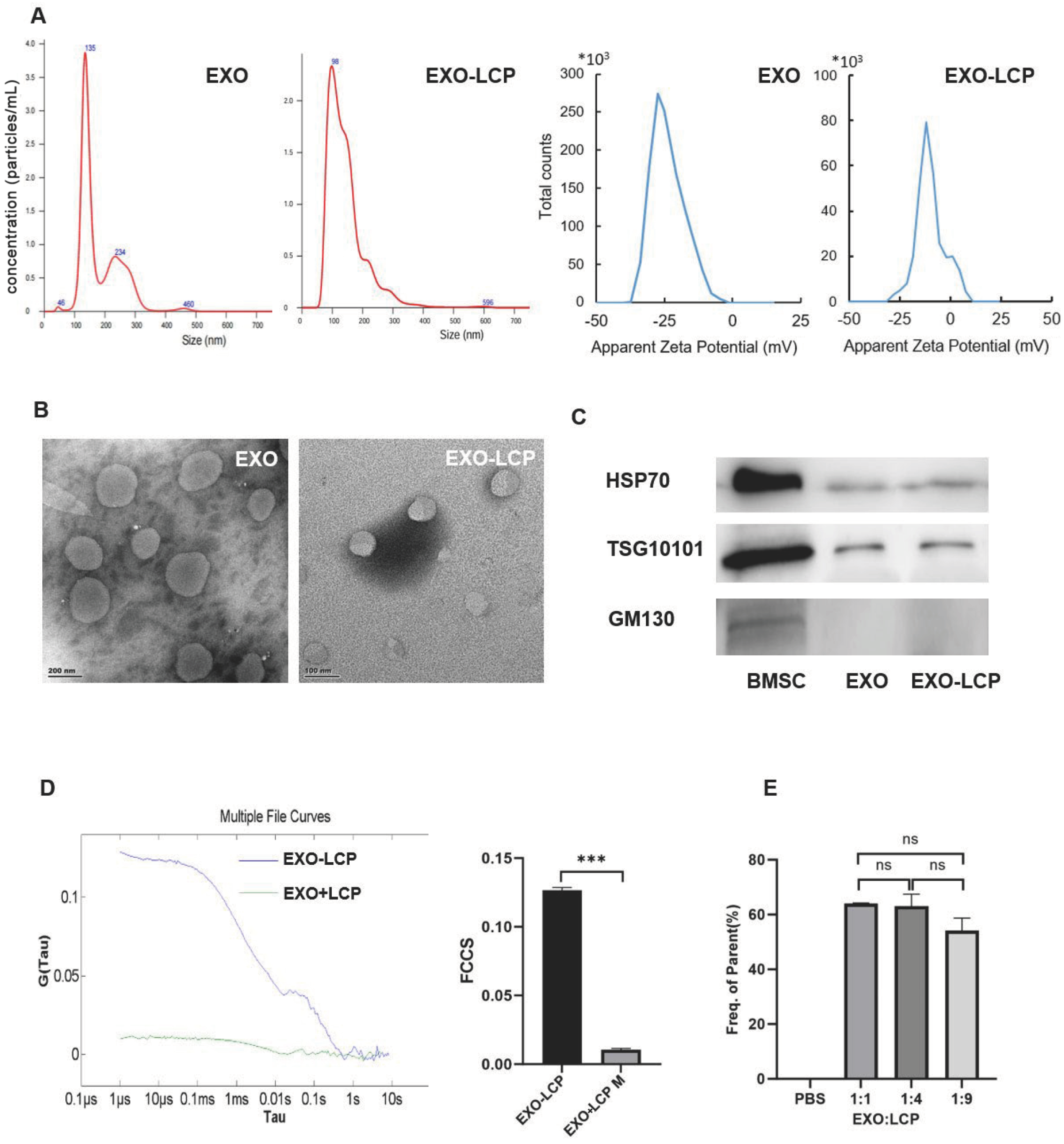

3.1. Characterization of EXO-LCP-Fused Membrane Formulations and Determination of the Optimal Fusion Ratio

3.2. Uptake of Fused Membrane Formulations in Different Cells and Their Relevant Mechanisms

3.3. Lysosomal Escape of Fused Membrane Formulations in Cells

3.4. Transfection Efficiency of GFP-Loaded Fused Membrane Formulations in Different Cells

3.5. Assessment of the In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Fused Membrane Formulations

3.6. In Vivo Brain Targeting of Fused Membrane Formulations in a Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Animal Model

3.7. Beneficial Effects of miRNA210-Loaded Fused Membrane Formulations on Rat Behavior with Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMSC | bone marrow stromal cell |

| CaP | calcium phosphate |

| CCA | common carotid artery |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| EXO | exosome |

| ECA | external carotid artery |

| FCS | fluorescence correlation spectroscopy |

| ICA | internal carotid artery |

| IS | ischemic stroke |

| LCP | lipid calcium phosphate |

| NP | nanoparticle |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| NTA | nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | polydispersity index |

| TEM | transmission electron microscope |

| T-LCP | AMD3100-modified targeted LCP |

References

- Paul, S.; Candelario-Jalil, E. Emerging neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of ischemic stroke: An overview of clinical and preclinical studies. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 335, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Xie, Y.; Bai, J.; Guan, J.; Qi, H.; Sun, J. Targeted pathophysiological treatment of ischemic stroke using nanoparticle-based drug delivery system. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Jeon, M.; Jung, H.N.; Lee, W.; Hwang, J.-E.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.; Im, H.-J. M1 Macrophage-Derived Exosome-Mimetic Nanovesicles with an Enhanced Cancer Targeting Ability. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 2862–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, S.; Hou, L.; Zhu, D.; Yin, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y. Therapeutic Effects of Simultaneous Delivery of Nerve Growth Factor mRNA and Protein via Exosomes on Cerebral Ischemia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Sun, C.; Zhou, S.; Xu, D.; Zhao, J. Exosomes Derived from CXCR4-Overexpressing BMSC Promoted Activation of Microvascular Endothelial Cells in Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8814239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xunian, Z.; Kalluri, R. Biology and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 3100–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Varshney, A.; Bajaj, R.; Pokharkar, V. Exosomes as New Generation Vehicles for Drug Delivery: Biomedical Applications and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Huang, Y. Bioinspired exosome-like therapeutics and delivery nanoplatforms. Biomaterials 2020, 242, 119925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Fan, M.; Huang, D.; Li, B.; Xu, R.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y. Clodronate-loaded liposomal and fibroblast-derived exosomal hybrid system for enhanced drug delivery to pulmonary fibrosis. Biomaterials 2021, 271, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles with an asymmetric lipid bilayer coating for siRNA delivery to the tumor. J. Control Release 2012, 158, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucia, M.; Jankowski, K.; Reca, R.; Wysoczynski, M.; Bandura, L.; Allendorf, D.J.; Zhang, J.; Ratajczak, J.; Ratajczak, M.Z. CXCR4-SDF-1 signalling, locomotion, chemotaxis and adhesion. J. Mol. Histol. 2004, 35, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B. Recent Advances in CXCL12/CXCR4 Antagonists and Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lu, J.; Xia, J. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3183–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendi, H.; Yazdimamaghani, M.; Hu, M.; Sultanpuram, N.; Wang, J.; Moody, A.S.; McCabe, E.; Zhang, J.; Graboski, A.; Li, L.; et al. Nanoparticle Delivery of miR-122 Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Meng, L.; Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Gong, T. A Novel Perspective on Ischemic Stroke: A Review of Exosome and Noncoding RNA Studies. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chen, Y.; Ke, Z.; Pang, M.; Yang, B.; Feng, F.; Wu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, B.; Zheng, X.; et al. Exosomes derived from miRNA-210 overexpressing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells protect lipopolysaccharide induced chondrocytes injury via the NF-κB pathway. Gene 2020, 751, 144764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, T. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes carrying E3 ubiquitin ligase ITCH attenuated cardiomyocyte apoptosis by mediating apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2023, 33, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.Y.; Kang, H.L.; Duan, W.; Zheng, J.; Li, Q.N.; Zhou, Z.J. MicroRNA-210 Promotes Accumulation of Neural Precursor Cells Around Ischemic Foci After Cerebral Ischemia by Regulating the SOCS1-STAT3-VEGF-C Pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e005052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longa, E.Z.; Weinstein, P.R.; Carlson, S.; Cummins, R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 1989, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, M.; Gronewold, J.; Scharf, A.-C.; Schuhmann, M.K.; Langhauser, F.; Hopp, S.; Mencl, S.; Geuss, E.; Leinweber, J.; Guthmann, J.; et al. Validity and Reliability of Neurological Scores in Mice Exposed to Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Stroke 2019, 50, 2875–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sanberg, P.R.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Lu, M.; Willing, A.E.; Sanchez-Ramos, J.; Chopp, M. Intravenous Administration of Human Umbilical Cord Blood Reduces Behavioral Deficits After Stroke in Rats. Stroke 2001, 32, 2682–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.L.; Chen, H.Z.; Gao, X.L. Lipid-coated calcium phosphate nanoparticle and beyond: A versatile platform for drug delivery. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, W.; Wang, H.; Bao, L.; Li, G.; Li, T.; Song, S.; Li, H.; Hao, J.; Sun, J. Resveratrol Protects PC12 Cell against 6-OHDA Damage via CXCR4 Signaling Pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 730121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Xu, T.; Jiang, W. Dexmedetomidine protects PC12 cells from ropivacaine injury through miR-381/LRRC4 /SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway. Regen. Ther. 2020, 14, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Pan, J.J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.Y. Native and Bioengineered Exosomes for Ischemic Stroke Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 619565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Han, Z.; Song, D.; Peng, Y.; Xiong, M.; Chen, Z.; Duan, S.; Zhang, L. Engineered Exosome for Drug Delivery: Recent Development and Clinical Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 7923–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Mu, X.; Zhao, C.; Teng, W. The Role of SDF-1/CXCR4/CXCR7 in Neuronal Regeneration after Cerebral Ischemia. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Pang, Y.; Su, Z.; Zheng, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Niu, P.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Enriched environment enhances angiogenesis in ischemic stroke through SDF-1/CXCR4/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Signal 2024, 124, 111464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EXO:LCP | Size (mm) | PDI | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCP | 97.32 ± 2.26 | 0.291 ± 0.01 | 14.4 ± 0.63 |

| 1:9 | 75.15 ± 0.37 | 0.252 ± 0.01 | −7.55 ± 2.13 |

| 1:4 | 87.32 ± 2.57 | 0.268 ± 0.01 | −8.30 ± 1.40 |

| 1:1 | 90.79 ± 1.31 | 0.293 ± 0.02 | −14.3 ± 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Mi, J.; Xu, Z.; Yang, C.; Qin, J.; Zhang, H. Fused Membrane-Targeted Nanoscale Gene Delivery System Based on an Asymmetric Membrane Structure for Ischemic Stroke. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101357

Shi J, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Wang J, Mi J, Xu Z, Yang C, Qin J, Zhang H. Fused Membrane-Targeted Nanoscale Gene Delivery System Based on an Asymmetric Membrane Structure for Ischemic Stroke. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(10):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101357

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jing, Xinyi Zhao, Yue Zhang, Zitong Zhao, Jing Wang, Jia Mi, Zhaowei Xu, Chunhua Yang, Jing Qin, and Hong Zhang. 2025. "Fused Membrane-Targeted Nanoscale Gene Delivery System Based on an Asymmetric Membrane Structure for Ischemic Stroke" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 10: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101357

APA StyleShi, J., Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Z., Wang, J., Mi, J., Xu, Z., Yang, C., Qin, J., & Zhang, H. (2025). Fused Membrane-Targeted Nanoscale Gene Delivery System Based on an Asymmetric Membrane Structure for Ischemic Stroke. Pharmaceutics, 17(10), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101357