Progress in Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery Research—Focus on Nanoformulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

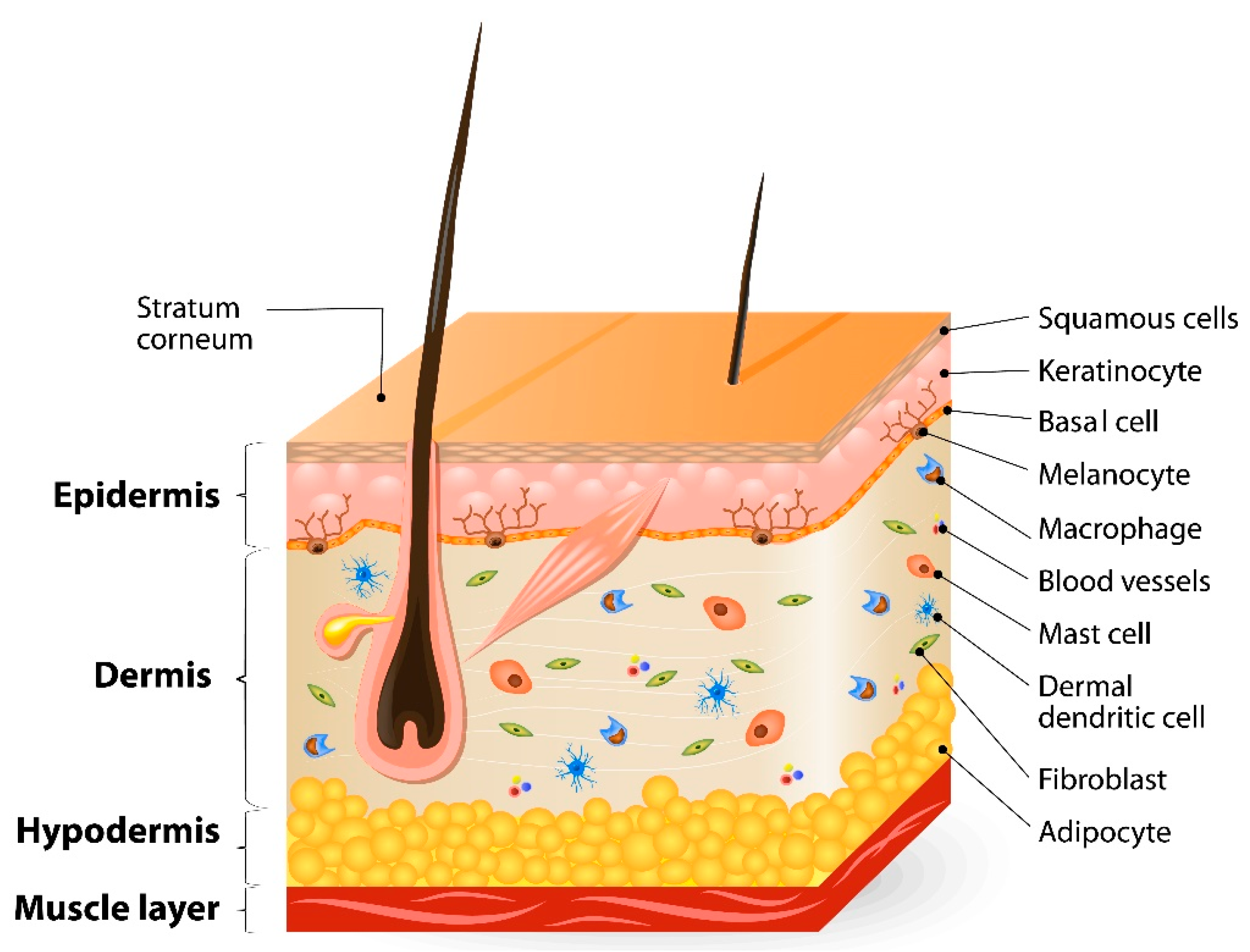

2. Drug Delivery through the skin

2.1. Structure of the Skin and Its Barrier Function

2.2. Penetration Pathways through the Stratum Corneum (SC)

2.3. Skin Models with Different Complexity

3. Skin Penetration

3.1. Biophysical Aspects of the Skin Penetration and Permeation

3.2. Enhancement of Skin Penetration/Permeation: Chemical and Physical Strategies

3.3. Penetration of Cosmetics vs. Therapeutic Formulations

4. Liquid and Semisolid Topical/Transdermal Formulations

4.1. Classical Topical Formulations

4.2. Film Forming Formulations

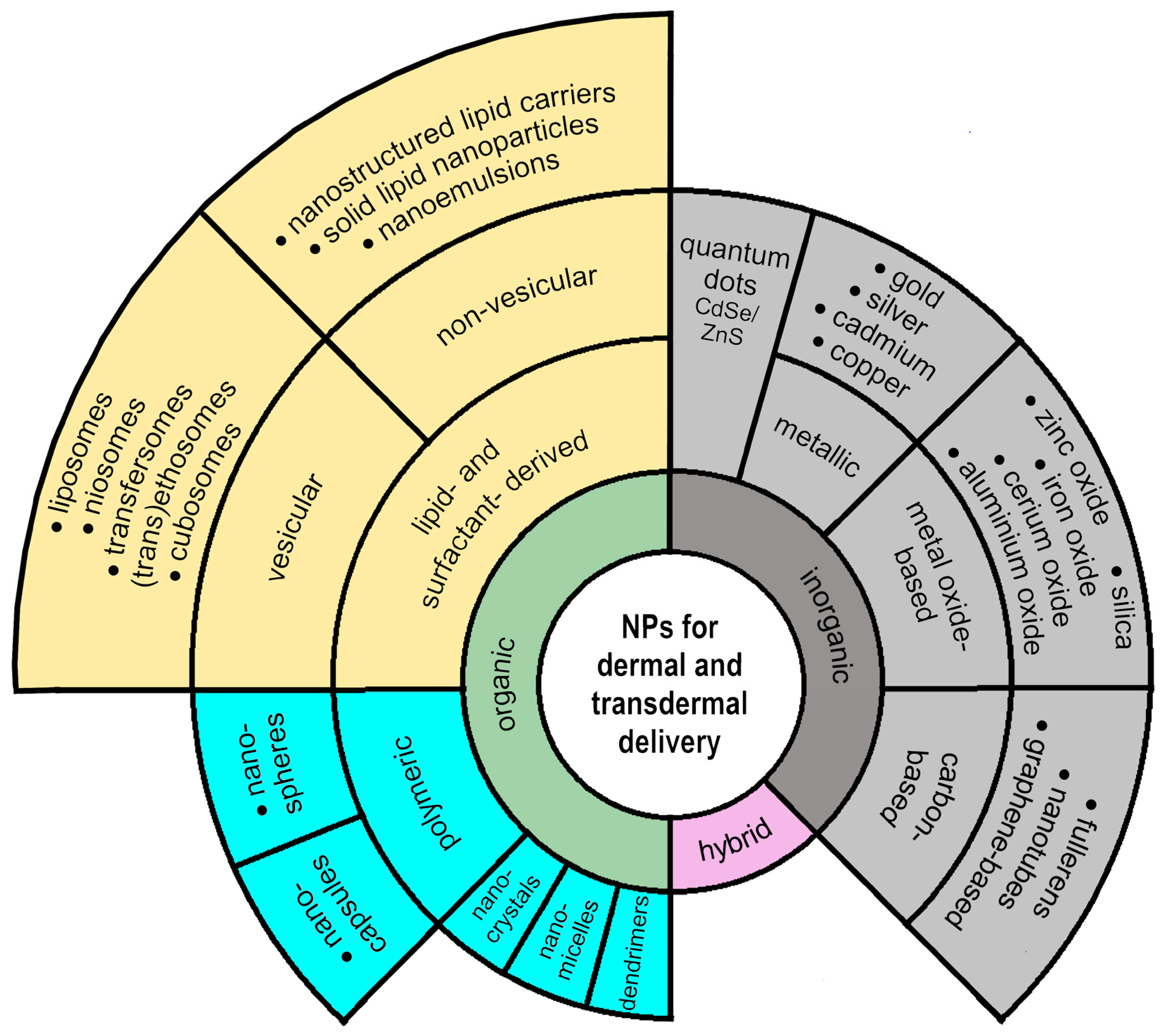

4.3. Advanced (Trans)dermal Formulations

5. Methods for Studying Skin Penetration and Formulations

5.1. In Vitro/Ex Vivo Methods

5.1.1. Traditional Diffusion Chambers

5.1.2. Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA)

5.1.3. Skin-on-Chip (SoC) Microfluidic Systems

5.2. In Vivo Methods

5.2.1. Transdermal Microdialysis

5.2.2. Dermal Open-Flow Microperfusion

5.2.3. Tape Stripping

5.3. Advanced Analytical Techniques

5.3.1. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Skin Penetration Studies

5.3.2. AFM-IR Spectroscopy for Skin Penetration Studies

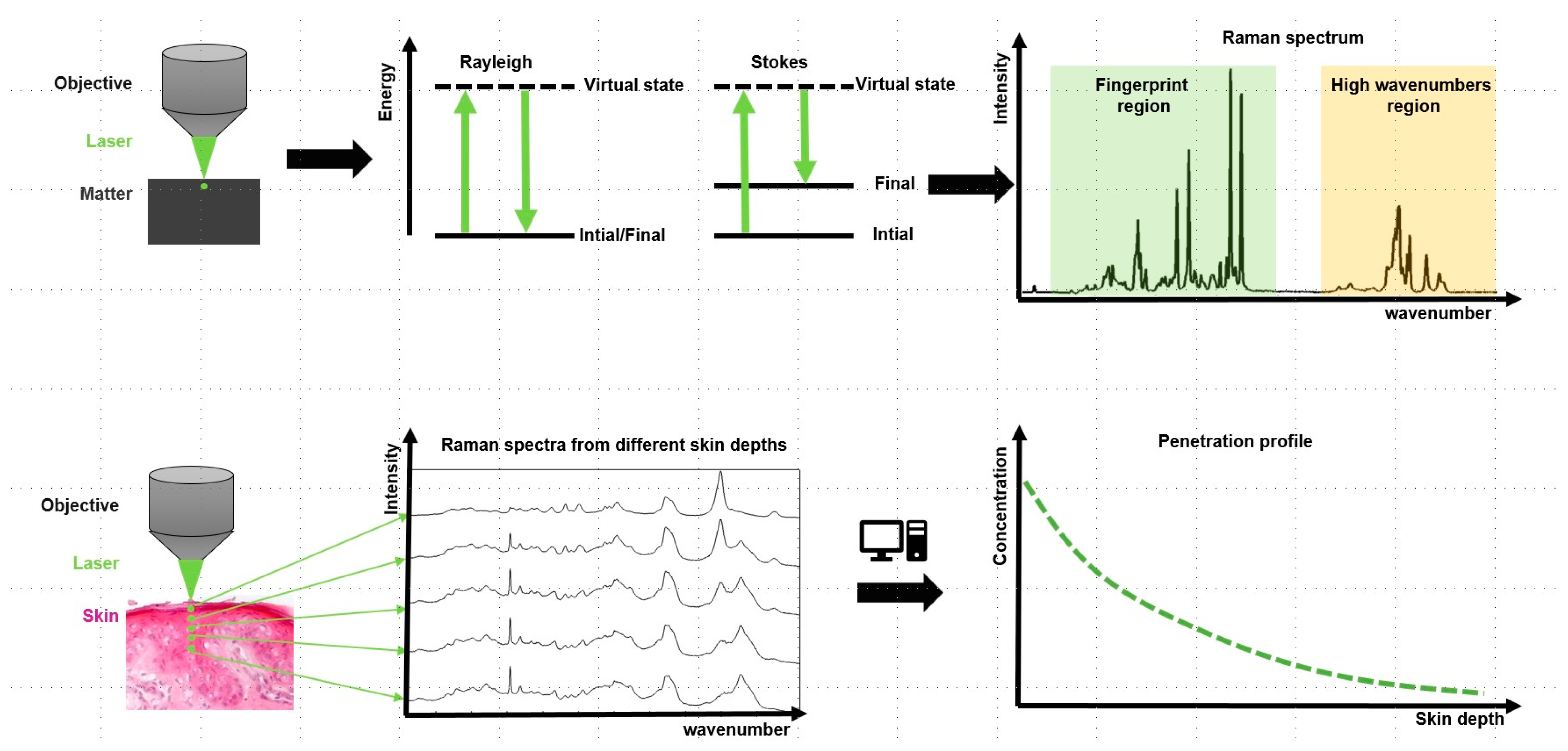

5.3.3. Confocal Raman Spectroscopy (CRS)

5.3.4. Soft X-ray Scanning

6. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling of the Skin Penetration

6.1. Homogenized Membrane Model

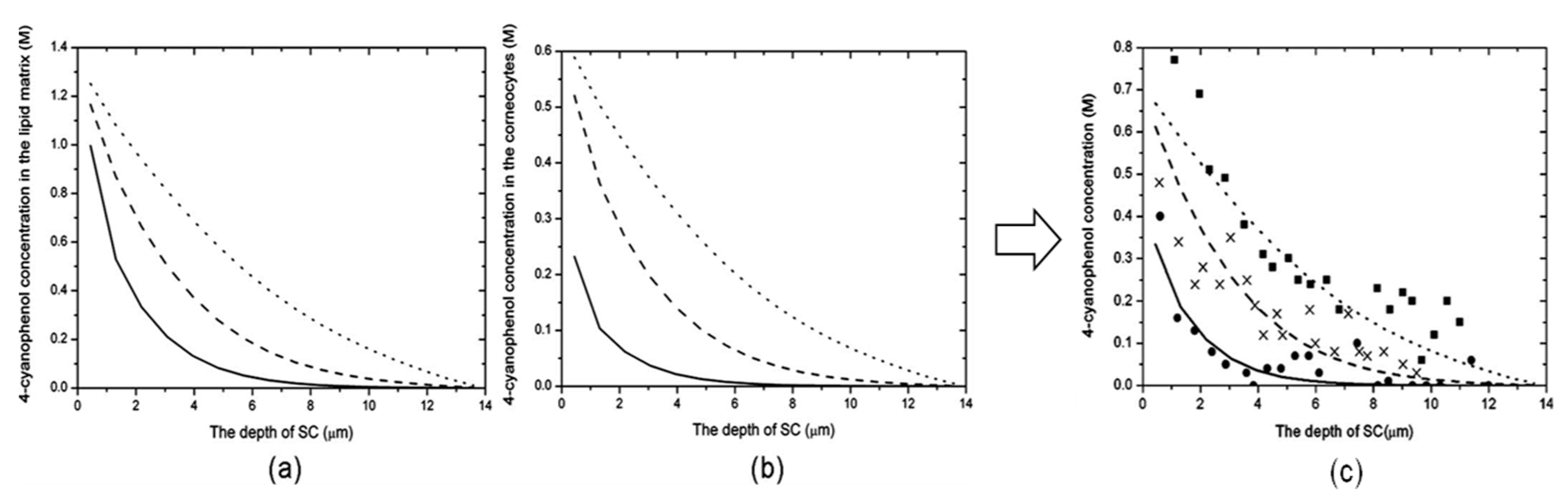

6.2. Microscopic Modeling of SC Permeation Pathways

7. Outlook—Current Approaches and Research Trends

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Souto, E.B.; Baldim, I.; Oliveira, W.P.; Rao, R.; Yadav, N.; Gama, F.M.; Mahant, S. SLN and NLC for topical, dermal, and transdermal drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertz, P.W.; van den Bergh, B. The physical, chemical and functional properties of lipids in the skin and other biological barriers. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1998, 91, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, F.H.; Freeman, J.W.; DeVore, D. Viscoelastic properties of human skin and processed dermis. Ski. Res. Technol. 2001, 7, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M. Epidermal Lipids, Barrier Function, and Desquamation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1983, 80, S44–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawana, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Ohno, Y.; Kihara, A. Comparative profiling and comprehensive quantification of stratum corneum ceramides in humans and mice by LC/MS/MS S. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichner, A.; Sonnenberger, S.; Dobner, B.; Hauss, T.; Schroeter, A.; Neubert, R.H.H. Localization of methyl-branched ceramide EOS species within the long-periodicity phase in stratum corneum lipid model membranes: A neutron diffraction study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 2911–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousel, J.; Nadaban, A.; Saghari, M.; Pagan, L.; Zhuparris, A.; Theelen, B.; Gambrah, T.; van der Wall, H.E.C.; Vreeken, R.J.; Feiss, G.L.; et al. Lesional skin of seborrheic dermatitis patients is characterized by skin barrier dysfunction and correlating alterations in the stratum corneum ceramide composition. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Ponec, M. The skin barrier in healthy and diseased state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, K.C. Barrier function of the skin: “La Raison d’Etre” of the epidermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.F.; Fan, Y.B. Enhancing Permeation of Drug Molecules Across the Skin via Delivery in Nanocarriers: Novel Strategies for Effective Transdermal Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tfayli, A.; Jamal, D.; Vyumvuhore, R.; Manfait, M.; Baillet-Guffroy, A. Hydration effects on the barrier function of stratum corneum lipids: Raman analysis of ceramides 2, III and 5. Analyst 2013, 138, 6582–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, M. Skin Barrier Function and the Microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, J.P.; Maibach, H.I.; Dragicevic, N. Targets in Dermal and Transdermal Delivery and Classification of Penetration Enhancement Methods. In Percutaneous Penetration Enhancers Chemical Methods in Penetration Enhancement: Drug Manipulation Strategies and Vehicle Effects; Dragicevic, N., Maibach, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Otberg, N.; Patzelt, A.; Rasulev, U.; Hagemeister, T.; Linscheid, M.; Sinkgraven, R.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J. The role of hair follicles in the percutaneous absorption of caffeine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, L.; Avlasevich, Y.; Zwicker, P.; Thiede, G.; Landfester, K.; Keck, C.M.; Meinke, M.C.; Darvin, M.E.; Kramer, A.; Müller, G.; et al. Release of the model drug SR101 from polyurethane nanocapsules in porcine hair follicles triggered by LED-derived low dose UVA light. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Évora, A.S.; Adams, M.J.; Johnson, S.A.; Zhang, Z. Corneocytes: Relationship between Structural and Biomechanical Properties. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 34, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yin, R.; Ma, L.; Li, H.; Qian, X.; Zhang, H. 3D skin models along with skin-on-a-chip systems: A critical review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, M.J.; Jüngel, A.; Rimann, M.; Wuertz-Kozak, K. Advances in the Biofabrication of 3D Skin in vitro: Healthy and Pathological Models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhar, B.; Das, E.; Manikumar, K.; Mandal, B.B. 3D Bioprinted Human Skin Model Recapitulating Native-Like Tissue Maturation and Immunocompetence as an Advanced Platform for Skin Sensitization Assessment. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2303312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.W. Dermatological Formulations: Percutaneous Absorption; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hadgraft, J.; Guy, R. Biotechnological Aspects of Transport Across Human Skin. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2004, 21, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, T.; Talukder, M.M.U. Chemical Enhancer: A Simplistic Way to Modulate Barrier Function of the Stratum Corneum. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Penetration enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovácik, A.; Kopecná, M.; Hrdinová, I.; Opálka, L.; Bettex, M.B.; Vávrová, K. Time-Dependent Differences in the Effects of Oleic Acid and Oleyl Alcohol on the Human Skin Barrier. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 6237–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bian, J.; Hantash, B.M.; Albakr, L.; Hibbs, D.E.; Xiang, X.; Xie, P.; Wu, C.; Kang, L. Enhanced skin retention and permeation of a novel peptide via structural modification, chemical enhancement, and microneedles. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 606, 120868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhong, W.; Xi, C.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, H.; Du, S. Study of the skin-penetration promoting effect and mechanism of combined system of curcumin liposomes prepared by microfluidic chip and skin penetrating peptides TD-1 for topical treatment of primary melanoma. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 643, 123256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, S.; Yan, G. Improving the direct penetration into tissues underneath the skin with iontophoresis delivery of a ketoprofen cationic prodrug. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentzsch, M.; Wawrzinek, R.; Zelle-Rieser, C.; Strandt, H.; Bellmann, L.; Fuchsberger, F.F.; Schulze, J.; Busmann, J.; Rademacher, J.; Sigl, S.; et al. Specific Protein Antigen Delivery to Human Langerhans Cells in Intact Skin. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhanker, Y.; Mbano, M.N.; Ponto, T.; Espartero, L.J.L.; Yamada, M.; Prow, T.; Benson, H.A.E. Comparison of physical enhancement technologies in the skin permeation of methyl amino levulinic acid (mALA). Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 610, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Jung, J.H.; Tadros, A.R.; Prausnitz, M.R. Tolerability, acceptability, and reproducibility of topical STAR particles in human subjects. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on Cosmetic Products. 2009. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/47f167ec-b5db-4ec9-9d12-3d807bf3e526_en (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use. Volume 311. 2001. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/directive-200183ec-european-parliament-and-council-6-november-2001-community-code-relating-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices, Amending Di-rective 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC (Text with EEA Relevance.). Volume 117. 2017. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0745 (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- European Pharmacopoiea (Ph. Eur.). Monograph. In Semisolid Dosage Forms for Cutaneous Use, 11th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare: Strasbourg, France, 2023.

- Kapoor, K.; Gräfe, N.; Herbig, M.E. Topical Film-Forming Solid Solutions for Enhanced Dermal Delivery of the Retinoid Tazarotene. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 2779–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, A.; Green, L.J.; Selmer, J.; Praestegaard, M.; Gold, L.S.; Augustin, M.; Trial Investigator, G. A pooled analysis of randomized, controlled, phase 3 trials investigating the efficacy and safety of a novel, fixed dose calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate cream for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosso, J.; Sugarman, J.; Green, L.; Lain, T.; Levy-Hacham, O.; Mizrahi, R.; Gold, L.S. Efficacy and safety of microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide and microencapsulated tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Results from two phase 3 double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunter, D.J.; Daniels, R. New film forming emulsions containing Eudragit® NE and/or RS 30D for sustained dermal delivery of nonivamide. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 82, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunter, D.; Daniels, R. In vitro Skin Permeation and Penetration of Nonivamide from Novel Film-Forming Emulsions. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013, 26, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, R.; Hermann, S.; Lunter, D.J.; Daniels, R. Film-forming formulations containing porous silica for the sustained delivery of actives to the skin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 108, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennari, C.G.M.; Selmin, F.; Franzè, S.; Musazzi, U.M.; Quaroni, G.M.G.; Casiraghi, A.; Cilurzo, F. A glimpse in critical attributes to design cutaneous film forming systems based on ammonium methacrylate. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 41, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VCI-Position zum ECHA-Vorschlag zur Beschränkung von Polymer. Available online: https://www.vci.de/themen/chemikaliensicherheit/reach/vci-position-echa-vorschlag-beschraenkung-polymere-als-absichtlich-eingesetztes-mikroplastik.jsp (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Pantelić, I.; Lukić, M.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Jakovljević, D.; Nikolić, I.; Lunter, D.J.; Daniels, R.; Savić, S. Bacillus licheniformis levan as a functional biopolymer in topical drug dosage forms: From basic colloidal considerations to actual pharmaceutical application. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 142, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidberger, M.; Nikolic, I.; Pantelic, I.; Lunter, D. Optimization of Rheological Behaviour and Skin Penetration of Thermogelling Emulsions with Enhanced Substantivity for Potential Application in Treatment of Chronic Skin Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padula, C.; Nicoli, S.; Colombo, P.; Santi, P. Single-layer transdermal film containing lidocaine: Modulation of drug release. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 66, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.S.; Kim, J.; Park, J.W.; Jin, S.G. Novel acyclovir-loaded film-forming gel with enhanced mechanical properties and skin permeability. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 70, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamsai, B.; Soodvilai, S.; Opanasopit, P.; Samprasit, W. Topical Film-Forming Chlorhexidine Gluconate Sprays for Antiseptic Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljak, K.B.; Zorec, B.S.; Matjaz, M.G. Nanocellulose-Based Film-Forming Hydrogels for Improved Outcomes in Atopic Skin. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, N.; Balwierz, R.; Biernat, P.; Ochędzan-Siodłak, W.; Lipok, J. Natural Ingredients of Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems as Permeation Enhancers of Active Substances through the Stratum Corneum. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 3278–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoS. Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- PubMed. National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Xia, Y.; Cao, K.; Jia, R.Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Xia, H.M.; Xu, Y.X.; Xie, Z.L. Tetramethylpyrazine-loaded liposomes surrounded by hydrogel based on sodium alginate and chitosan as a multifunctional drug delivery System for treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 193, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Sun, Y.F.; Bi, D.H.; Peng, S.Y.; Li, M.; Liu, H.M.; Zhang, L.B.; Tao, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhu, J.T. Regulating Size and Charge of Liposomes in Microneedles to Enhance Intracellular Drug Delivery Efficiency in Skin for Psoriasis Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Cheng, Z.E.; Yi, H.X. NIR light-activatable dissolving microneedle system for melanoma ablation enabled by a combination of ROS-responsive chemotherapy and phototherapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamie, C.; Elmowafy, E.; Ragaie, M.H.; Attia, D.A.; Mortada, N.D. Assessment of antifungal efficacy of itraconazole loaded aspasomal cream: Comparative clinical study. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaidan, O.A.; Zafar, A.; Al-Ruwaili, R.H.; Yasir, M.; Alzarea, S.I.; Alsaidan, A.A.; Singh, L.; Khalid, M. Niosomes gel of apigenin to improve the topical delivery: Development, optimization, ex vivo ex vivo permeation, antioxidant study, and in vivo evaluation. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, A.; Shabbir, K.; Din, F.U.; Shafique, S.; Zaidi, S.S.; Almari, A.H.; Alqahtani, T.; Maryiam, A.; Khan, M.M.; Al Fatease, A.; et al. Co-delivery of amphotericin B and pentamidine loaded niosomal gel for the treatment of Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghtaderi, M.; Bazzazan, S.; Sorourian, G.; Sorourian, M.; Akhavanzanjani, Y.; Noorbazargan, H.; Ren, Q. Encapsulation of Thymol in Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMa)-Based Nanoniosome Enables Enhanced Antibiofilm Activity and Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Elkady, O.A.; Amer, M.A.; Noshi, S.H. Exploiting response surface D-optimal design study for preparation and optimization of spanlastics loaded with miconazole nitrate as a model antifungal drug for topical application. J. Pharm. Innov. 2023, 18, 2402–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, K.; Din, F.U.; Jamshaid, H.; Afza, R.; Khan, S.U.; Malik, M.; Ali, Z.; Batool, S.; Zeb, A.; Yousaf, A.M.; et al. Metformin HCl-loaded transethosomal gel; development, characterization, and antidiabetic potential evaluation in the diabetes-induced rat model. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, Z.; Jamshaid, T.; Sajid-ur-Rehman, M.; Jamshaid, U.; Gad, H.A. Novel Transethosomal Gel Containing Miconazole Nitrate; Development, Characterization, and Enhanced Antifungal Activity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S.; Shabbir, K.; Din, F.U.; Khan, S.U.; Ali, Z.; Khan, B.A.; Kim, D.W.; Khan, G.M. Nitazoxanide and quercetin co-loaded nanotransfersomal gel for topical treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with macrophage targeting and enhanced anti-leishmanial effect. Heliyon 2023, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tai, Z.G.; Ma, J.Y.; Miao, F.Z.; Xin, R.J.; Shen, C.E.; Shen, M.; Zhu, Q.A.; Chen, Z.J. Lycorine transfersomes modified with cell-penetrating peptides for topical treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Alsaidan, O.A.; Mohanty, D.; Zafar, A.; Das, S.; Gupta, J.K.; Khalid, M. Development of Soft Luliconazole Invasomes Gel for Effective Transdermal Delivery: Optimization to In-Vivo Antifungal Activity. Gels 2023, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.Z.; Huang, Q.B.; Song, Y.T.; Feng, X.Q.; Zeng, L.J.; Liu, Z.H.; Hu, X.M.; Tao, C.; Wang, L.; Qi, Y.F.; et al. Cubosomes-assisted transdermal delivery of doxorubicin and indocyanine green for chemo-photothermal combination therapy of melanoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabahar, K.; Uthumansha, U.; Elsherbiny, N.; Qushawy, M. Enhanced Skin Permeation and Controlled Release of β-Sitosterol Using Cubosomes Encrusted with Dissolving Microneedles for the Management of Alopecia. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.; Thakkar, H. Formulation Development of Fast Dissolving Microneedles Loaded with Cubosomes of Febuxostat: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albash, R.; Yousry, C.; Al-Mahallawi, A.M.; Alaa-Eldin, A.A. Utilization of PEGylated cerosomes for effective topical delivery of fenticonazole nitrate: In-vitro characterization, statistical optimization, and in-vivo assessment. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, F.; Saba, A.; Yasin, H.; Buabeid, M.; Noreen, S.; Khan, A.K.; Murtaza, G. Fabrication of solid lipid nanoparticles-based patches of paroxetine and their ex-vivo permeation behaviour. Artif. Cell Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samee, A.; Usman, F.; Wani, T.A.; Farooq, M.; Shah, H.S.; Javed, I.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, R.; Zargar, S.; Kausar, S. Sulconazole-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antifungal Activity: In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. Molecules 2023, 28, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukuntla, J.; Peterson-Sockwell, S.; Clark, B.A.; Godage, N.H.; Gionfriddo, E.; Bolla, P.K.; Boddu, S.H.S. Design and Preclinical Evaluation of Nicotine-Stearic Acid Conjugate-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Transdermal Delivery: A Technical Note. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Di Muzio, L.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Laneri, S.; Cairone, F.; Cesa, S.; Petralito, S.; Paolicelli, P.; Casadei, M.A. Dual delivery of ginger oil and hexylresorcinol with lipid nanoparticles for the effective treatment of cutaneous hyperpigmentation. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folle, C.; Sánchez-López, E.; Mallandrich, M.; Díaz-Garrido, N.; Suñer-Carbó, J.; Halbaut, L.; Carvajal-Vidal, P.; Marqués, A.M.; Espina, M.; Badia, J.; et al. Semi-solid functionalized nanostructured lipid carriers loading thymol for skin disorders. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 651, 123732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanou, K.; Barbosa, A.I.; Detsi, A.; Lima, S.A.C.; Reis, S. Development and characterization of gel-like matrix containing genistein for skin application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 90, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.; El-Kayal, M. Novel anti-psoriatic nanostructured lipid carriers for the cutaneous delivery of luteolin: A comprehensive in-vitro and in-vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 191, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnisa, A.; Chettupalli, A.K.; Alazragi, R.S.; Alelwani, W.; Bannunah, A.M.; Barnawi, J.; Amarachinta, P.R.; Jandrajupalli, S.B.; Elamine, B.A.; Mohamed, O.A.; et al. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers to Enhance the Bioavailability and Solubility of Ranolazine: Statistical Optimization and Pharmacological Evaluations. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, N.; Rincón, M.; Silva-Abreu, M.; Sosa, L.; Pesantez-Narvaez, J.; Calpena, A.C.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Mallandrich, M. Semi-Solid Dosage Forms Containing Pranoprofen-Loaded NLC as Topical Therapy for Local Inflammation: In Vitro, Ex Vivo and In Vivo Evaluation. Gels 2023, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadag, S.; Narayan, R.; Nayak, A.S.; Ardila, D.C.; Sant, S.; Nayak, Y.; Garg, S.; Nayak, U.Y. Development and preclinical evaluation of microneedle-assisted resveratrol loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for localized delivery to breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 606, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunprasert, K.; Pornpitchanarong, C.; Piemvuthi, C.; Siraprapapornsakul, S.; Sripeangchan, S.; Lertsrimongkol, O.; Opanasopit, P.; Patrojanasophon, P. Nanostructured lipid carrier-embedded polyacrylic acid transdermal patches for improved transdermal delivery of capsaicin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 173, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, G.D.S.; Loureiro, A.I.S.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Barros, P.A.B.; Halicki, P.C.B.; Ramos, D.F.; Marinho, M.A.G.; Vaiss, D.P.; Vaz, G.R.; Yurgel, V.C.; et al. Toward a Platform for the Treatment of Burns: An Assessment of Nanoemulsions vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers Loaded with Curcumin. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, M.H.; Abu Lila, A.S.; El-Nahas, H.M.; Ibrahim, T.M. Optimization of Potential Nanoemulgels for Boosting Transdermal Glimepiride Delivery and Upgrading Its Anti-Diabetic Activity. Gels 2023, 9, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhasso, B.; Ghori, M.U.; Conway, B.R. Development of a Nanoemulgel for the Topical Application of Mupirocin. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita, V.G.; Vavia, P. Bromocriptine Nanoemulsion-Loaded Transdermal Gel: Optimization Using Factorial Design, In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almehmady, A.M.; Ali, S.A. Transdermal Film Loaded with Garlic Oil-Acyclovir Nanoemulsion to Overcome Barriers for Its Use in Alleviating Cold Sore Conditions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myburgh, J.; Liebenberg, W.; Willers, C.; Dube, A.; Gerber, M. Investigation and Evaluation of the Transdermal Delivery of Ibuprofen in Various Characterized Nano-Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, S.; Sahu, P.; Begum, J.P.S.; Kashaw, S.K.; Pandey, A.; Semwal, P.; Sharma, R. Formulation and assessment of penetration potential of Risedronate chitosan nanoparticles loaded transdermal gel in the management of osteoporosis: In vitro and ex vivo screening. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Pandey, M.; Thu, H.E.; Kaur, T.; Jia, G.W.; Ying, P.C.; Xian, T.M.; Abourehab, M.A.S. Hyaluronic acid functionalization improves dermal targeting of polymeric nanoparticles for management of burn wounds: In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmash, E.Z.; Attiany, L.M.; Ali, D.; Assaf, S.M.; Alkrad, J.; Alyami, H. Development and Characterization of Transdermal Patches Using Novel Thymoquinone-L-Arginine-Based Polyamide Nanocapsules for Potential Use in the Management of Psoriasis. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radmard, A.; Banga, A.K. Microneedle-Assisted Transdermal Delivery of Lurasidone Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.Q.; Zheng, Y.X.; Pan, X.H.; Huang, Y.P.; Kang, Y.X.; Zhong, W.Y.; Xu, K.M. Enzyme-me diate d fabrication of nanocomposite hydrogel microneedles for tunable mechanical strength and controllable transdermal efficiency. Acta Biomater. 2024, 174, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilawar, N.; Ur-Rehman, T.; Shah, K.U.; Fatima, H.; Alhodaib, A. Development and Evaluation of PLGA Nanoparticle-Loaded Organogel for the Transdermal Delivery of Risperidone. Gels 2022, 8, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, B.N.; Lima, A.L.; Cardoso, C.O.; Cunha, M.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M. Follicle-Targeted Delivery of Betamethasone and Minoxidil Co-Entrapped in Polymeric and Lipid Nanoparticles for Topical Alopecia Areata Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Deng, H.Y.; Liang, B.H.; Li, R.X.; Li, H.P.; Ke, Y.A.; Zhu, H.L. A convergent synthetic platform of hydrogels enclosing prednisolone-loaded nanoparticles for the treatment of chronic actinic dermatitis. Mater. Technol. 2023, 38, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.; Shekh, M.; Song, J.X.; Sun, Q.; Dai, H.; Xue, V.W.; Liu, S.S.; Du, B.; Zhou, G.Q.; Stadler, F.J.; et al. ISX9 loaded thermoresponsive nanoparticles for hair follicle regrowth. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, Y.C.; Choi, W.I. Super-Antioxidant Vitamin A Derivatives with Improved Stability and Efficacy Using Skin-Permeable Chitosan Nanocapsules. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatem, S.; Elkheshen, S.A.; Kamel, A.O.; Nasr, M.; Moftah, N.H.; Ragai, M.H.; Elezaby, R.S.; El Hoffy, N.M. Functionalized chitosan nanoparticles for cutaneous delivery of a skin whitening agent: An approach to clinically augment the therapeutic efficacy for melasma treatment. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1212–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavkova, M.; Lazov, C.; Spassova, I.; Kovacheva, D.; Tibi, I.P.E.; Stefanova, D.; Tzankova, V.; Petrov, P.D.; Yoncheva, K. Formulation of Budesonide-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles into Hydrogels for Local Therapy of Atopic Dermatitis. Gels 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.Y.; Sun, Y.Y.; Han, M.S.; Chen, D.Y.; He, X.Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Sun, K.X. Triptorelin nanoparticle-loaded microneedles for use in assisted reproductive technology. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, B.; Ricci, C.; Macchi, T.; Günday, C.; Munafò, S.; Maleki, H.; Pratesi, F.; Tempesti, V.; Cristallini, C.; Bruschini, L.; et al. A Straightforward Method to Produce Multi-Nanodrug Delivery Systems for Transdermal/Tympanic Patches Using Electrospinning and Electrospray. Polymers 2023, 15, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.; Kim, M.; Won, H.; Jung, A.; Kim, J.; Koo, Y.; Lee, N.K.; Baek, S.H.; Han, U.; Park, C.G.; et al. Secured delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor using human serum albumin-based protein nanoparticles for enhanced wound healing and regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.X.; Sun, Y.F.; Nie, L.; Shavandi, A.; Yunusov, K.E.; Hua, Y.J.; Jiang, G.H. Fabrication of carboxymethyl cellulose/hyaluronic acid/polyvinylpyrrolidone composite pastes incorporation of minoxidil-loaded ferulic acid-derived lignin nanoparticles and valproic acid for treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darade, A.R.; Lapteva, M.; Ling, V.C.; Kalia, Y.N. Polymeric micelles for cutaneous delivery of the hedgehog pathway inhibitor TAK-441: Formulation development and cutaneous biodistribution in porcine and human skin. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 644, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.; Rawas-Qalaji, M.; El Hosary, R.; Jagal, J.; Ahmed, I.S. Formulation and optimization of ivermectin nanocrystals for enhanced topical delivery. Int. J. Pharm. X 2023, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, I.; Miocic, S.; Pepic, I.; Simic, D.; Filipovic-Grcic, J. Efficacy and Safety of Azelaic Acid Nanocrystal-Loaded In Situ Hydrogel in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.C.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Pan, Y.X.; Liang, S.L.; Hu, Y.H.; Wang, L. Multifunctional fucoidan-loaded Zn-MOF-encapsulated microneedles for MRSA-infected wound healing. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursy, D.; Balwierz, R.; Groch, P.; Biernat, P.; Byrski, A.; Kasperkiewicz, K.; Ochedzan-Siodlak, W. Nanoparticles coated by chloramphenicol in hydrogels as a useful tool to increase the antibiotic release and antibacterial activity in dermal drug delivery. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Huwaij, R.; Abed, M.; Hamed, R. Innovative transdermal doxorubicin patches prepared using greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles for breast cancer treatment. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhu, Y.T.; Li, K.Q.; Hao, K.; Chai, Y.Q.; Jiang, H.Y.; Lou, C.; Yu, J.C.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.L.; et al. Microneedles loaded with cerium-manganese oxide nanoparticles for targeting macrophages in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.E.; Yan, A.Q.; Qiang, W.; Ruan, R.; Yang, C.B.; Ma, K.; Sun, H.M.; Liu, M.X.; Zhu, H.D. Selective Delivery of Tofacitinib Citrate to Hair Follicles Using Lipid-Coated Calcium Carbonate Nanocarrier Controls Chemotherapy-Induced Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereig, S.; El-Zaafarany, G.M.; Arafa, M.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.M.A. Boosting the anti-inflammatory effect of self-assembled hybrid lecithin-chitosan nanoparticles via hybridization with gold nanoparticles for the treatment of psoriasis: Elemental mapping and in vivo modeling. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1726–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, P.; Akbari, A.; Saadatkish, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Kouhi, M.; Bodaghi, M. Acceleration of Wound Healing in Rats by Modified Lignocellulose Based Sponge Containing Pentoxifylline Loaded Lecithin/Chitosan Nanoparticles. Gels 2022, 8, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.M.; Chen, H.; Chu, Z.Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, B.J.; Sun, J.A.; Lai, W.; Ma, Y.; He, Y.L.; Qian, H.S.; et al. A multifunctional composite hydrogel as an intrinsic and extrinsic coregulator for enhanced therapeutic efficacy for psoriasis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.S.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Cheng, S.H.; Shao, X.Z.; Liu, S.L.; Lu, W.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, P.P.; Yao, Q.Q. Ibuprofen-Loaded ZnO Nanoparticle/Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers for Dual-Stimulus Sustained Release of Drugs. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 5535–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todosijević, M.N.; Savić, M.M.; Batinić, B.B.; Marković, B.D.; Gašperlin, M.; Ranđelović, D.V.; Lukić, M.Ž.; Savić, S.D. Biocompatible microemulsions of a model NSAID for skin delivery: A decisive role of surfactants in skin penetration/irritation profiles and pharmacokinetic performance. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 496, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, T.; Savić, S.; Batinić, B.; Marković, B.; Schmidberger, M.; Lunter, D.; Savić, M.; Savić, S. Combined use of biocompatible nanoemulsions and solid microneedles to improve transport of a model NSAID across the skin: In vitro and in vivo studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 125, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, V.; Ilić, T.; Nikolić, I.; Marković, B.; Čalija, B.; Cekić, N.; Savić, S. Tacrolimus-loaded lecithin-based nanostructured lipid carrier and nanoemulsion with propylene glycol monocaprylate as a liquid lipid: Formulation characterization and assessment of dermal delivery compared to referent ointment. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 569, 118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Bhunia, P.; Samanta, A.P.; Orasugh, J.T.; Chattopadhyay, D. Transdermal therapeutic system: Study of cellulose nanocrystals influenced methylcellulose-chitosan bionanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.Gov. Search Clinical Studies and Their Results. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Wong, W.F.; Ang, K.P.; Sethi, G.; Looi, C.Y. Recent Advancement of Medical Patch for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Med. Lith. 2023, 59, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/search_product.cfm (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Bird, D.; Ravindra, N.M. Transdermal drug delivery and patches—An overview. Med. Devices Sens. 2020, 3, e10069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Aqil, M.; Talegaonkar, S.; Azeem, A.; Sultana, Y.; Ali, A. Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery Techniques: An Extensive Review of Patents. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2009, 3, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO. The World Intellectual Property Organization. PATENTSCOPE—Search International and National Patent Collections. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/search.jsf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Mitragotri, S.; Langer, R. Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E. Skin permeation: The years of enlightenment. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 305, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Honeywell-Nguyen, P.L.; Gooris, G.S.; Ponec, M. Structure of the skin barrier and its modulation by vesicular formulations. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netzlaff, F.; Lehr, C.M.; Wertz, P.W.; Schaefer, U.F. The human epidermis models EpiSkin, SkinEthic and EpiDerm: An evaluation of morphology and their suitability for testing phototoxicity, irritancy, corrosivity, and substance transport. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005, 60, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebe, I.; Zsidai, L.; Zelkó, R. Novel modified vertical diffusion cell for testing of in vitro drug release (IVRT) of topical patches. HardwareX 2022, 11, e00293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józsa, L.; Nemes, D.; Peto, A.; Kósa, D.; Révész, R.; Bácskay, I.; Haimhoffer, A.; Vasvári, G. Recent Options and Techniques to Assess Improved Bioavailability: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Methods. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, T.J. Percutaneous Absorption. On the Relevance of in Vitro Data. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1975, 64, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Jain, S.; Lin, S. Transdermal iontophoretic delivery of tacrine hydrochloride: Correlation between in vitro permeation and in vivo performance in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 513, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Frempong, D.; Mishra, D.; Dogra, P. Microneedle-mediated transdermal delivery of naloxone hydrochloride for treatment of opioid overdose. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkó, B.; Garrigues, T.M.; Balogh, G.T.; Nagy, Z.K.; Tsinman, O.; Avdeef, A.; Takács-Novák, K. Skin–PAMPA: A new method for fast prediction of skin penetration. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 45, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Shen, M.; Li, H.; Duan, Y. A new PAMPA model proposed on the basis of a synthetic phospholipid membrane. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Nguyen, K.; Kerns, E.; Yan, Z.; Yu, K.R.; Shah, P.; Jadhav, A.; Xu, X. Highly predictive and interpretable models for PAMPA permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rácz, A.; Vincze, A.; Volk, B.; Balogh, G.T. Extending the limitations in the prediction of PAMPA permeability with machine learning algorithms. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 188, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnoki-Zách, J.; Mehes, E.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Isai, D.G.; Barany, N.; Bugyik, E.; Revesz, Z.; Paku, S.; Erdo, F.; Czirok, A. Development and Evaluation of a Human Skin Equivalent in a Semiautomatic Microfluidic Diffusion Chamber. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukács, B.; Bajza, A.; Kocsis, D.; Csorba, A.; Antal, I.; Iván, K.; Laki, A.J.; Erdo, F. Skin-on-a-Chip Device for Ex Vivo Monitoring of Transdermal Delivery of Drugs-Design, Fabrication, and Testing. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponmozhi, J.; Dhinakaran, S.; Kocsis, D.; Iván, K.; Erdo, F. Models for barrier understanding in health and disease in lab-on-a-chips. Tissue Barriers 2024, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, D.; Klang, V.; Schweiger, E.-M.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Mihály, A.; Pongor, C.; Révész, Z.; Somogyi, Z.; Erdő, F. Characterization and ex vivo evaluation of excised skin samples as substitutes for human dermal barrier in pharmaceutical and dermatological studies. Ski. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, D.; Horváth, S.; Kemény, Á.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Pongor, C.; Molnár, R.; Mihály, A.; Farkas, D.; Naszlady, B.M.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Drug Delivery through the Psoriatic Epidermal Barrier—A “Skin-On-A-Chip” Permeability Study and Ex Vivo Optical Imaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoio, P.; Oliva, A. Skin-on-a-Chip Technology: Microengineering Physiologically Relevant In Vitro Skin Models. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdo, F.; Hashimoto, N.; Karvaly, G.; Nakamichi, N.; Kato, Y. Critical evaluation and methodological positioning of the transdermal microdialysis technique. A review. J. Control. Release 2016, 233, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenlenz, M.; Höfferer, C.; Magnes, C.; Schaller-Ammann, R.; Schaupp, L.; Feichtner, F.; Ratzer, M.; Pickl, K.; Sinner, F.; Wutte, A.; et al. Dermal PK/PD of a lipophilic topical drug in psoriatic patients by continuous intradermal membrane-free sampling. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 81, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, W.L.; Skinner, M.F.; Kanfer, I. Comparison of tape stripping with the human skin blanching assay for the bioequivalence assessment of topical clobetasol propionate formulations. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 13, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, J.C.; Pagitsch, E.; Valenta, C. Comparison of ATR-FTIR spectra of porcine vaginal and buccal mucosa with ear skin and penetration analysis of drug and vehicle components into pig ear. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 50, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppel, M.; Baurecht, D.; Holper, E.; Mahrhauser, D.; Valenta, C. Validation of the combined ATR-FTIR/tape stripping technique for monitoring the distribution of surfactants in the stratum corneum. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 472, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, L.; Kulovits, E.M.; Petz, R.; Ruthofer, J.; Baurecht, D.; Klang, V.; Valenta, C. Penetration monitoring of drugs and additives by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy/tape stripping and confocal Raman spectroscopy—A comparative study. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 130, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirot, F.; Kalia, Y.N.; Stinchcomb, A.L.; Keating, G.; Bunge, A.; Guy, R.H. Characterization of the permeability barrier of human skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuley, W.J.; Chavda-Sitaram, S.; Mader, K.T.; Tetteh, J.; Lane, M.E.; Hadgraft, J. The effects of esterified solvents on the diffusion of a model compound across human skin: An ATR-FTIR spectroscopic study. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 447, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kästner, B.; Marschall, M.; Hornemann, A.; Metzner, S.; Patoka, P.; Cortes, S.; Wübbeler, G.; Hoehl, A.; Rühl, E.; Elster, C. Compressed AFM-IR hyperspectral nanoimaging. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcott, C.; Padalkar, M.; Pleshko, N. 3.23 Infrared and Raman Microscopy and Imaging of Biomaterials at the Micro and Nano Scale☆. In Comprehensive Biomaterials II; Ducheyne, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 498–518. [Google Scholar]

- Kemel, K.; Deniset-Besseau, A.; Baillet-Guffroy, A.; Faivre, V.; Dazzi, A.; Laugel, C. Nanoscale investigation of human skin and study of skin penetration of Janus nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 579, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, D.; Kichou, H.; Döme, K.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Révész, Z.; Antal, I.; Erdő, F. Structural and Functional Analysis of Excised Skins and Human Reconstructed Epidermis with Confocal Raman Spectroscopy and in Microfluidic Diffusion Chambers. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielfeldt, S.; Bonnier, F.; Byrne, H.J.; Chourpa, I.; Dancik, Y. Monitoring dermal penetration and permeation kinetics of topical products; the role of Raman microspectroscopy. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 156, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confocal Raman Microscopy, 2nd ed.; Jan Toporski, T.D., Hollricher, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 66, p. 596. [Google Scholar]

- Caspers, P.J.; Nico, C.; Bakker Schut, T.C.; de Sterke, J.; Pudney, P.D.A.; Curto, P.R.; Illand, A.; Puppels, G.J. Method to quantify the in vivo skin penetration of topically applied materials based on confocal Raman spectroscopy. Transl. Biophotonics 2019, 1, e201900004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albèr, C.; Brandner, B.D.; Björklund, S.; Billsten, P.; Corkery, R.W.; Engblom, J. Effects of water gradients and use of urea on skin ultrastructure evaluated by confocal Raman microspectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 2470–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egawa, M.; Sato, Y. In vivo evaluation of two forms of urea in the skin by Raman spectroscopy after application of urea-containing cream. Ski. Res. Technol. 2015, 21, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourbaj, G.; Gaiser, A.; Bielfeldt, S.; Lunter, D. Assessment of penetration and permeation of caffeine by confocal Raman spectroscopy in vivo and ex vivo by tape stripping. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krombholz, R.; Liu, Y.L.; Lunter, D.J. In-Line and Off-Line Monitoring of Skin Penetration Profiles Using Confocal Raman Spectroscopy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, F.; Goh, C.F.; Haque, T.; Rahma, A.; Lane, M.E. Dermal Delivery of Diclofenac Sodium-In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, G.E.; Calienni, M.N.; Alonso, S.D.; Alvira, F.C.; Montanari, J. Raman Spectroscopy to Monitor the Delivery of a Nano-Formulation of Vismodegib in the Skin. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krombholz, R.; Lunter, D. A New Method for In-Situ Skin Penetration Analysis by Confocal Raman Microscopy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourousias, G.; Pascolo, L.; Marmorato, P.; Ponti, J.; Ceccone, G.; Kiskinova, M.; Gianoncelli, A. High-resolution scanning transmission soft X-ray microscopy for rapid probing of nanoparticle distribution and sufferance features in exposed cells. X-ray Spectrom. 2015, 44, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabell, C.A.; Nugent, K.A. Imaging cellular architecture with X-rays. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010, 20, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.A.; Babin, S.; Celestre, R.S.; Chao, W.L.; Conley, R.P.; Denes, P.; Enders, B.; Enfedaque, P.; James, S.; Joseph, J.M.; et al. An ultrahigh-resolution soft x-ray microscope for quantitative analysis of chemically heterogeneous nanomaterials. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Klossek, A.; Flesch, R.; Rancan, F.; Weigand, M.; Bykova, I.; Bechtel, M.; Ahlberg, S.; Vogt, A.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; et al. Influence of the skin barrier on the penetration of topically-applied dexamethasone probed by soft X-ray spectromicroscopy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 118, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Klossek, A.; Flesch, R.; Ohigashi, T.; Fleige, E.; Rancan, F.; Frombach, J.; Vogt, A.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Schrade, P.; et al. Core-multishell nanocarriers: Transport and release of dexamethasone probed by soft X-ray spectromicroscopy. J. Control. Release 2016, 242, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, G.; Ohigashi, T.; Yuzawa, H.; Kosugi, N.; Flesch, R.; Rancan, F.; Vogt, A.; Rühl, E. Improved Skin Permeability after Topical Treatment with Serine Protease: Probing the Penetration of Rapamycin by Scanning Transmission X-ray Microscopy. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 12213–12222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, G.; Ohigashi, T.; Yuzawa, H.; Kosugi, N.; Flesch, R.; Rancan, F.; Vogt, A.; Rühl, E. Soft X-ray scanning transmission microscopy as a selective probe of topical dermal drug delivery: The role of petrolatum and occlusion. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2023, 266, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Han, L.J.; Saib, O.; Lian, G.P. In Silico Prediction of Percutaneous Absorption and Disposition Kinetics of Chemicals. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, T.E.; Li, H.Q.; Lee, M.Y.; Piechota, P.; Nicol, B.; Pickles, J.; Pendlington, R.; Sorrell, I.; Baltazar, M.T. Application of physiologically based kinetic (PBK) modelling in the next generation risk assessment of dermally applied consumer products. Toxicol. Vitro 2020, 63, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Diffusion modeling of percutaneous absorption kinetics: 2. Finite vehicle volume and solvent deposited solids. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 90, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1975; p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Coderch, L.; Collini, I.; Carrer, V.; Barba, C.; Alonso, C. Assessment of Finite and Infinite Dose In Vitro Experiments in Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, F.; Caspers, P.J.; Puppels, G.J.; Lane, M.E. Franz Cell Diffusion Testing and Quantitative Confocal Raman Spectroscopy: In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, A.S.; Chandrasekaran, S.K.; Shaw, J.E. Drug permeation through human skin: Theory and invitro experimental measurement. AIChE J. 1975, 21, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Blankschtein, D.; Langer, R. Evaluation of solute permeation through the stratum corneum: Lateral bilayer diffusion as the primary transport mechanism. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.M.; Chen, L.J.; Lian, G.P.; Han, L.J. Determination of partition and binding properties of solutes to stratum corneum. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 398, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Lian, G.P.; Han, L.J. Modeling Transdermal Permeation. Part I. Predicting Skin Permeability of Both Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Solutes. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.P.; Chen, L.J.; Pudney, P.D.A.; Mélot, M.; Han, L.J. Modeling Transdermal Permeation. Part 2. Predicting the Dermatopharmacokinetics of Percutaneous Solute. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 2551–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

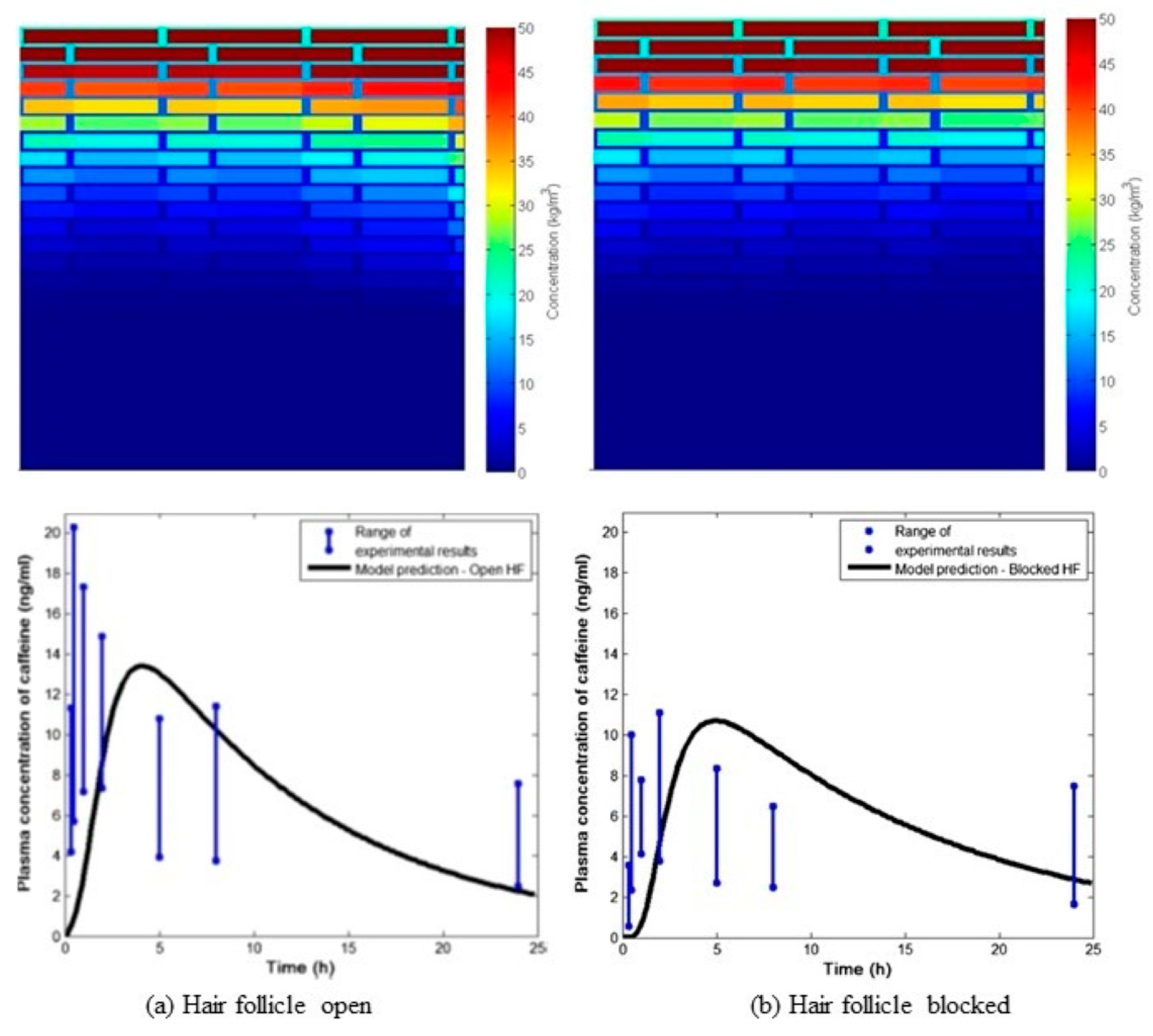

- Kattou, P.; Lian, G.; Glavin, S.; Sorrell, I.; Chen, T. Development of a Two-Dimensional Model for Predicting Transdermal Permeation with the Follicular Pathway: Demonstration with a Caffeine Study. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 2036–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.F.; Kasting, G.B.; Nitsche, J.M. A multiphase microscopic diffusion model for stratum corneum permeability. II. estimation of physicochemical parameters, and application to a large permeability database. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 3024–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundborg, M.; Wennberg, C.; Lidmar, J.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E.; Norlén, L. Skin permeability prediction with MD simulation sampling spatial and alchemical reaction coordinates. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 3837–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasentin, N.; Lian, G.P.; Cai, Q. In Silico Prediction of Stratum Corneum Partition Coefficients via COSMOmic and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 2719–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Bak, S.U.; La, H.N.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, H.H.; Eom, H.J.; Lee, B.K.; Kang, H.A. Efficient transdermal delivery of functional protein cargoes by a hydrophobic peptide MTD 1067. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kang, D.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.; Jeong, W.-J. Self-Assembled Skin-Penetrating Peptides with Controlled Supramolecular Properties for Enhanced Transdermal Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vander Straeten, A.; Sarmadi, M.; Daristotle, J.L.; Kanelli, M.; Tostanoski, L.H.; Collins, J.; Pardeshi, A.; Han, J.L.; Varshney, D.; Eshaghi, B.; et al. A microneedle vaccine printer for thermostable COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wei, T.; Xu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Chao, Y.; Lu, J.; Xu, J.; Zhu, J.; Yan, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Non-invasive transdermal delivery of biomacromolecules with fluorocarbon-modified chitosan for melanoma immunotherapy and viral vaccines. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solution | Emulsion | Suspension | Gel | Ointment | Cream | Paste | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of phases, n | n = 1 | n > 1 | n = 2 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n > 1 | n > 1 |

| Consistency | liquid | liquid | liquid | semisolid | semisolid | semisolid | semisolid |

| Main excipients | water; alcohol or oil | water; alcohol; oil; emulsifier | water; alcohol or oil; finely dispersed solids | water; alcohol; gel former | oil; white soft paraffin; wax; constancy agents; emulsifier (in water absorbing ointments) | water; oil; white soft paraffin; wax; constancy agents; emulsifier | ointment or cream |

| Subgroups and phasing | hydrophilic; lipophilic | hydrophilic (oil-in-water, O/W); lipophilic (water-in-oil, W/O) | hydrophilic; lipophilic | hydrophilic (hydrogel); lipophilic (oleogel) | hydrophilic; lipophilic; water absorbing: lipophilic | hydrophilic; lipophilic | hydrophilic; lipophilic |

| Galenic characteristics | high spreadability, especially on hair-rich skin | high spreadability, especially on hair-rich skin | high spreadability, especially on hair-rich skin | hydrogels: cooling effect; oleogels: occlusive | hydrophilic: cooling effect; water absorbing: partially occlusive, water uptake | hydrophilic: “lighter” skin feeling; lipophilic: partially occlusive | more solid than corresponding ointment or cream |

| Delivery System | Description/ Excipients | Active Ingredient (Category) | Route | Dosage Form | Purpose | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid- and surfactant-based vesicular NPs | Liposomes/ phospholipids, cholesterol | Tetramethylpyrazine (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant) | Transdermal | Gel | Development of multifunctional hydrogel drug delivery system based on tetramethylpyrazine-loaded liposomes surrounded by sodium alginate-chitosan hydrogel for treating atopic dermatitis | [52] |

| Liposomes/ anionic: DPPC, DSPE-mPEG2000, cholesterol; cationic: DOTAP, DOPE | Dexamethasone (corticosteroid) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Design and evaluation of dexamethasone-loaded cationic and anionic liposomes integrated in hyaluronic acid-based microneedles, to enhance intracellular drug delivery efficiency in psoriatic skin, by regulating size and surface charge of drug-loaded liposomes | [53] | |

| Liposomes/ cholesterol, hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine, DSPE-mPEG2000 | Doxorubicin hydrochloride (chemotherapeutic); Indocyanine green (photosensitizer) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Design and characterization of a near-infrared (NIR) light-activatable dissolving, polyvinylpyrrolidone microneedle system incorporating liposomes co-loaded with the active oxygen species (ROS)-responsive doxorubicin prodrug and the photosensitizer indocyanine green, to allow a transdermal delivery method with controllable drug release/activation and effective imaging guidance for melanoma ablation | [54] | |

| Aspasomes– ascorbyl palmitate-based liposomes/ ascorbyl palmitate, cholesterol, phospholipid | Itraconazole (antifungal agent) | Topical | Cream | Design and clinical evaluation of itraconazole-loaded aspasomes (newer antioxidant generation of liposomes) enclosed in topical oil-in-water cream as a potent nano-sized delivery system for effective treatment of dermal fungal infections | [55] | |

| Niosomes/ cholesterol, Span® 60 | Apigenin (herbal bioactive compound; antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory effects) | Transdermal | Gel | Development of apigenin-loaded niosomes incorporated into chitosan gel to improve transdermal delivery and therapeutic efficacy | [56] | |

| Niosomes/ cholesterol, Span® 60, Span® 80 | Amphotericin B (antifungal); Pentamidine (antiparasitic) | Transdermal | Gel | Preparation of amphotericin B-pentamidine-loaded niosomes and incorporation into chitosan gel for better skin penetration, sustained release and improved anti-leishmanial activity in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis | [57] | |

| Niosomes/ cholesterol, Span® 60 | Thymol (herbal antimicrobial agent) | Topical | Gel | Development and evaluation of thymol-encapsulated niosomes incorporated into gelatin methacryloyl polymeric hydrogel to improve thymol antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity and wound healing | [58] | |

| Spanlastics—elastic niosomes/ Span® 60; Tween® 20, 60 or 80, or Brij® 35, 58, or 97 | Miconazole nitrate (antifungal) | Topical | Gel | Design and evaluation of miconazole nitrate-loaded spanlastics incorporated in carbopol gel for topical application in deeply sated skin fungal infections | [59] | |

| Transethosomes/ Phospholipon® 90G, Tween® 80, ethanol | Metformin hydrochloride (antidiabetic) | Transdermal | Gel | Design, optimization and evaluation of metformin hydrochloride transethosomes incorporated into chitosan gel to provide sustained release, reduce side effects and improve transdermal drug delivery and therapeutic effect | [60] | |

| Transethosomes/ lecithin, oleic acid, ethanol | Miconazole nitrate (antifungal) | Topical | Gel | Development and evaluation of miconazole nitrate-loaded transethosomes incorporated into carbopol gel to enhance skin permeability and antifungal activity | [61] | |

| Transfersomes/ Phospholipon® 90G, Tween® 80 | Nitazoxanide (antiparasitic); Quercetin (natural flavonoid; antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-leishmanial effects) | Topical | Gel | Development, characterization and evaluation of nitazoxanide and quercetin co-loaded nanotransfersomes incorporated into chitosan gel for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with the aim to achieve passive targeting of dermal macrophages and improve therapeutic effect | [62] | |

| CPP-modified transfersomes/ soybean phospholipid, DOTAP, sodium cholate hydrate; modification: CPP Stearyl-R5H3) | Lycorine (isoquinoline alkaloid; anti-cancer antiviral, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects) | Topical | Gel | Development and evaluation of lycorine-oleic acid ionic complex-loaded CPP-modified cationic transfersomes incorporated into carbopol gel, for topical treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, aiming to enhance skin and tumor permeability and drug delivery | [63] | |

| Invasomes/ soy lecithin, terpene (citronella) oil, ethanol | Luliconazole (antifungal) | Topical | Gel | Development and characterization of luliconazole-loaded soft invasomes incorporated into carbopol gel to increase drug skin penetration and topical antifungal efficacy | [64] | |

| Cubosomes/ glyceryl monooleate, Pluronic® F-127 | Doxorubicin hydrochloride (chemotherapeutic); Indocyanine green (photothermal agent) | Transdermal | Gel | Development of doxorubicin and indocyanine green co-loaded cubosomes (incorporatd in xanthan gum gel), as a promising transdermal nanocarrier to enhance drug permeation across the skin and improve efficacy of melanoma treatment by combination chemo-photothermal therapy | [65] | |

| Cubosomes/ glyceryl monooleate, Pluronic® F-127 | β-Sitosterol (natural phytosterol; for promoting hair growth) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Design and evaluation of β-sitosterol loaded cubosomes integrated with dissolving microneedles (hyaluronic acid and polyvinyl pirolidone K90 matrix) as a novel dermal delivery system for β-sitosterol, to obtain increased skin penetration and controlled release for the treatment of alopecia | [66] | |

| Cubosomes/ glyceryl monooleate, polyvinyl alcohol 6000 | Febuxostat (xanthine oxidase inhibitor, for hyperuricemia treatment) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Design and evaluation of febuxostat-loaded cubosomes entrapped into fast dissolving microneedles to enhance drug permeation, bioavailability and effectiveness, and avoid side effect in the treatment of gout | [67] | |

| PEGylated cerosomes—ceramide-enclosed tubular vesicles/ egg yolk phosphatidylcholine, stearylamine, ceramide IIIB; PEGylated surfactant: Brij® 52 or Brij® 97 | Fenticonazole nitrate (antifungal agent) | Topical | Suspension (vesicles dispersion) | Design and evaluation of fenticonazole nitrate-loaded PEGylated cerosomes as a novel topical drug delivery system for effective treatment of fungal skin infections | [68] | |

| Lipid- and surfactant-based non-vesicular NPs | SLNs/ glyceryl monostearate, Tween® 80 | Paroxetine (antidepressant) | Transdermal | Patch | Fabrication of paroxetine-loaded SLNs incorporated in transdermal patch to increase drug absorption and bioavailability | [69] |

| SLNs/ Phospholipon® 90 H, glyceryl monostearate, Tween® 20 | Sulconazole (antifungal) | Topical | Gel | Formulation design, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of sulconazole-loaded SLNs incorporated into carbopol-based topical gel for enhanced skin penetration and antifungal activity | [70] | |

| SLNs/ Compritol® 888 ATO, poloxamer 188 | Nicotine (for nicotine replacement therapy) | Transdermal | Gel | Development and evaluation of nicotine–stearic acid conjugate-loaded SLNs incorporated in hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) gel for nicotine transdermal delivery in the treatment of smoking cessation | [71] | |

| SLNs/ Precirol® ATO 5, poloxamer 188; | Hexylresorcinol (whitening agent); Ginger oil (inhibition of tyrosinase activity and microftalmia transcription factor, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory agent) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Development, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of stable lipid NPs as carriers for co-delivery of 4-hexylresorcinol and ginger oil for the effective cutaneous hyperpigmentation treatment | [72] | |

| NLCs/ Precirol® ATO 5, Labrafac™ lipophile WL 1349 or ginger oil, poloxamer 188, sucrose distearate or Span® 85 | ||||||

| NLCs/ glyceryl behenate, PEG-8 caprylic/capric glycerides, Tween® 20, poloxamer 188, or phosphatidylcholine, chitosan | Thymol (antimicrobial natural compound) | Topical | Gel | Development, optimization and evaluation of thymol-loaded functionalized/surface-modified NLCs dispersed in carbomer gelling systems for topical use against acne vulgaris | [73] | |

| NLCs/ Softisan® 649 and Miglyol® 812-based, freeze-dried | Genistein (natural isoflavone; antioxidant) | Topical | Gel | Development and characterization of gel-like matrix containing genistein-loaded NLCs to improve drug retention on the skin; evaluation of the developed genistein delivery system for potential use in skin protection and UV radiation-associated skin diseases | [74] | |

| NLCs/ Precirol® ATO 5; geranium oil, tee tree oil, lavender oil; Tween® 80 | Luteolin (antipsoriatic) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Development and evaluation of novel luteolin-loaded NLCs comprising different anti-inflammatory oils to enhance luteolin skin deposition and augment its functionality in the treatment of psoriasis | [75] | |

| NLCs/ Precirol® ATO 5, oleic acid, Tween® 80 | Ranolazine (anti-anginal, anti-ischemic agent) | Transdermal | Gel | Development and evaluation of ranolazine-loaded NLCs incorporated into transdermal carbopol gel, to enhance drug bioavailability and improve the treatment efficacy of angina pectoris | [76] | |

| NLCs/ Precirol® ATO 5; castor oil/PEG-8 caprylic/capric glycerides; Tween® 80 | Pranoprofen (NSAID) | Topical | Gel | Desgn and evaluation of pranoprofen-loaded NLCs incorporated into Carbopol® 940- or Sepigel® 305-based gels as effective topical delivery system for the treatment of local skin inflammation | [77] | |

| NLCs/ glyceryl monostearate; Capryol® 90; poloxamer 188) | Resveratrol (natural polyphenol; anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, and anti-aging activities) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Fabrication and characterization of resveratrol-loaded NLCs incorporated into carbopol gel and administered via microneedle array delivery system to enable localized drug delivery and improved efficacy for breast cancer therapy | [78] | |

| NLCs/ cetyl palmitate; oleic acid; Transcutol P, limonene; polysorbate 80, polysorbate 20) | Capsaicin (active alkaloid of chilli peppers, Capsicum extract; analgesic, to treat pain-related symptoms) | Topical | Patch | Development and evaluation of capsaicin-loaded NLCs embedded in polyacrylic acid transdermal patches to improve skin delivery of capsaicin and reduce its skin adverse effects for the treatment of skeletomuscular and neuropathic pain | [79] | |

| Nanoemulsion/ medium chain triglycerides, Span® 80, Tween® 80; | Curcumin (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, wound-healing) | Topical | Emulsion (nano); | Development and evaluation of two types of curcumin-loaded lipid nanocarriers—nanoemulsion and NLCs—to select the most appropriate curcumin delivery platform for the treatment of skin burns | [80] | |

| NLCs/ medium chain triglycerides, glyceryl monostearate, Span® 80, Tween® 80 | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | |||||

| Nanoemulsion/ pepermint and bergamot oils; Tween® 80; Transcutol® P or PEG 400 | Glimepiride (oral hypoglycemic drug) | Transdermal | Gel | Preparation and evaluation of glimepiride-loaded nanoemulsion incorporated into different gels (carbopol-, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-, sodium alginate-, or HPMC-based) to enhance transdermal drug delivery and its therapeutic efficacy in diabetes treatment | [81] | |

| Nanoemulsion/ eucalyptus oil, Span® 80, Tween® 80 | Mupirocin (antibiotic) | Topical | Emulgel | Development, characterization and evaluation of mupirocin nanoemulgel, that is mupirocin-loaded nanoemulsion incorporated into carbopol hydrogel, characterized by high skin deposition and enhanced antibacterial effect, for targeting skin lesions | [82] | |

| Nanoemulsion/ Capmul® PG-8, Transcutol® P, Kolliphor® EL, Tween® 80, propylene glycol | Bromocriptine mesylate (semisynthetic ergot alkaloid; dopaminergic agonist, for Parkinson’s disease treatment) | Transdermal | Gel | Development and characterization of bromocriptine-loaded nanoemulsion incorporated into carbopol-based gel, as effective transdermal drug delivery system to enhance drug bioavailability, reduce side effects and increase patient compliance in the management of Parkinson’s disease | [83] | |

| Nanoemulsion/Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system/ oil: garlic oil; surfactant: Tween® 20/Span® 20 mixture; co-surfactant: propylene glycol | Acyclovir (antiviral drug); Garlic oil (antiviral effect) | Transdermal | Film | Formulation and evaluation of acyclovir and garlic oil-loaded self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system incorporated into hydroxypropyl cellulose transdermal film as a promising therapeutic approach in relieving cold sores symptoms | [84] | |

| Nanoemulsion/ evening primrose oil, Span® 60, Tween® 80; | Ibuprofen (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, NSAID) | Transdermal | Emulsion (nano); | Development and evaluation of three types of nanoparticulate transdermal delivery systems of ibuprofen—nanoemulsion, nanoemulgel, and polymeric NPs (polycaprolactone, polyvinyl alcohol, sucrose)—aiming to enhance skin permeation, leading to improved pain relief and patient compliance | [85] | |

| Nanoemulgel/ nanoemulsion + Carbopol® Ultrez 20 | Emulgel (nano); | |||||

| Polymeric NPs | Chitosan NPs | Risedronate sodium (anti-osteoporosis drug) | Transdermal | Gel | Formulation and in vitro/ex vivo evaluation of a novel transdermal gel loaded with risedronate-chitosan NPs to treat osteoporosis | [86] |

| Chitosan NPs functionalized with hyaluronic acid | Curcumin (natural polyphenol; anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, wound-healing, tissue regenerating, immunomodulatory, anti-cancer effects); Quercetin (natural polyphenol; antioxidant, antifibrotic, wound-healing, anti-inflammatory activity) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Development and evaluation of hyaluronic acid functionalized-curcumin and quercetin co-loaded polymeric NPs to improve dug skin targeting and efficacy in the treatment of burn wounds | [87] | |

| L-arginine-based polyamide NPs | Thymoquinone (antipsoriatic) | Transdermal | Patch | Synthesis and characterization of novel thymoquinone-loaded L-arginine-based polyamide nanocapsules incorporated into transdermal patches for potential management of psoriasis | [88] | |

| PLGA NPs/ poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Lurasidone (antipsychotic) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Development and evaluation of transdermal delivery system for lurasidone, namely lurasidone-loaded PLGA NPs incorporated into effervescent microneedles, to increase drug bioavailability and schizophrenia patient adherence | [89] | |

| PLGA NPs | Tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridinio)porphyrin (photosenzitizer, anti-cancer) | Transdermal | Gel miconeedles | Fabrication of drug-loaded PLGA NPs and incorporation into enzyme mediated nanocomposite hyaluronic acid-tyramine hydrogel microneedles with tunable mechanical strength and controllable transdermal efficiency in melanoma | [90] | |

| PLGA NPs | Risperidone (atypical antipsychotic drug) | Transdermal | System (NPs-loaded organogel) | Preparation and characterization of risperidone-loaded PLGA NPs incorporated into poloxamer lecithin organogel as a novel nanocarrier system for transdermal delivery of risperidone, in order to improve drug skin permeation and reduce side effects | [91] | |

| PCL NPs/ polycaprolactone (PCL), Tween® 80 | Betamethasone phosphate (corticosteroid); Minoxidil (hair regrowth agent, for alopecia) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Development and comparative evaluation of batamethasone and minoxidil co-loaded polymeric and lipidic NPs for enhanced targeted follicular drug delivery in treating alopecia | [92] | |

| Chitosan-coated PLGA NPs | Prednisolone (corticosteroid) | Topical | Gel | Development and evaluation of prednisolone-loaded polymeric NPs incorporated into poloxamer hydrogel to improve anti-inflammatory action and reduce side effects in the treatment of chronic actinic dermatitis | [93] | |

| Chitosan-grafted polymeric NPs/ chitosan, poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-N-isopropyl acrylamide—Poly(GMA-co-NIPAAm, Pluronic® F-127 | ISX9 (neurogenesis inducer, stimulates hair follicle growth) | Transdermal | System | Synthesis and characterization of ISX9-loaded thermoresponsive, biopolymer-based nanoparticulate drug delivery system, comprising chitosan-grafted Poly(GMA-co-NIPAAm) as the shell component and Pluronic® F-127 as the core polymer, to treat androgenetic alopecia | [94] | |

| Chitosan-coated nanocapsules/ chitosan, Pluronic® F-127 | Retinyl palmitate (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-wrinkle) | Topical | Lyophilized powder for suspension | Development and in vitro evaluation of vitamin A derivative-loaded chitosan-coated nanocapsules for effective skin delivery of retinyl palmitate, with enhanced stability, skin penetration and efficacy | [95] | |

| Functionalised chitosan NPs/ chitosan, functional additives: hyaluronic acid sodium salt and/or collagen | Alpha arbutin (natural hydroquinone derivative; skin whitening agent, tyrosinase inhibitor) | Topical | Gel | Formulation and evaluation of alpha arbutin-loaded functionalized chitosan NPs encapsulated in carbopol hydrogel to enhance drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy in melasma treatment | [96] | |

| Eudragit L 100 NPs | Budesonide (corticosteroid) | Topical | Gel | Development of pH-sensitive, budesonide-loaded NPs embedded into hydrogels for local therapy of atopic dermatitis in pediatric population | [97] | |

| Silk fibroin NPs | Triptorelin (gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Development and evaluation of silk fibroin-based microneedles for delivery of triptorelin-loaded silk fibroin NPs to improve relative bioavailability and tolerability of triptorelin for women undergoing assisted reproductive technology | [98] | |

| Polymeric NPs/fiber system/ Poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate fiber mashes decorated with PLGA NPs | Dexamethasone (corticosteroid, anti-inflammatory) | Transdermal/tympanic | Patch | Proof of concept of a dual drug-loaded patch based on rhodamine-loaded NPs and dexamethasone-loaded ultra-fine fibers, as an effective transdermal drug delivery system for the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions or sudden sensorineural hearing loss | [99] | |

| Human serum albumin-based protein NPs | Basic fibroblast growth factor, bFGF (accelerating angiogenesis and skin tissue regeneration, by promoting proliferation and migration of dermal cells for wound healing) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Development of recombinant bFGF protein-loaded human serum albumin NPs as a promising delivery platform for improved bFGF stability, sustained release and enhanced wound healing and tissue regeneration | [100] | |

| Ferulic acid-derived lignin NPs | Minoxidil (stimulation of hair follicle regrowth, for alopecia) | Transdermal | Nanocomposite paste | Development and evaluation of carboxymethyl cellulose/hyaluronic acid/polyvinylpyrrolidone-based composite paste system incorporating minoxidil-loaded NPs and valproic acid for the treatment of androgenic alopecia, with using roller-microneedles to create mechanical microchannels and enhance transdermal drug delivery and efficiency | [101] | |

| Micelles | Polymeric micelles/ D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) | TAK-441 (hedgehog pathway inhibitor, anti-cancer) | Topical | Gel | Development and evaluation of TAK-441-loaded TPGS micelles incorporated into HPMC hydrogel to enhance cutaneous drug delivery and deposition, thereby reducing systemic adverse effects, for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma | [102] |

| Nanocrystals | Nanocrystals/ Nanosuspension/ drug; stabilizer: poly(vinyl alcohol), sodium dodecyl sulfate, or Tween® 80 | Ivermectin (antiparasitic) | Topical | Cream | Preparation and characterization of ivermectin nanocrystales to improve drug solubility, skin penetration and efficacy when applied topically in the treatment of parasitic infections | [103] |

| Nanocrystals/ Nanosuspension/ drug; polysorbate 60 | Azelaic acid (antibacterial, anti-acne, anti-inflammatory, keratolytic activity) | Topical | Gel | Preparation and evaluation of azelaic acid nanocrystals-loaded in situ hidrogel (Pluronic® F-127, hyaluronic acid), characterized by improved efficacy and favorable safety for the treatment of acne vulgaris | [104] | |

| Metallic NPs | Hyaluronic acid-coated zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 NPs | Fucoidan, zinc (antimicrobial agent) | Dermal (subcutaneous) | Microneedle patch | Synthesis of multifunctional fucoidan-loaded zinc-metal organic framework-encapsulated microneedles for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected wound healing | [105] |

| Gold NPs and silica NPs | Chloramphenicol (antibiotic) | Topical | Gel | Investigation of carbopol-based hydrogels loaded with chloramphenicol-coated gold and silica NPs, as a promising strategy to increase dermal drug delivery, improve antimicrobial activity and reduce the concentration of antibiotic, thus improving its safety and efficacy | [106] | |

| Metal oxide NPs | Starch-coated iron oxide NPs | Doxorubicin hydrochloride (chemotherapeutic) | Transdermal | Patch | Fabrication of a non-invasive, innovative transdermal patch loaded with greenly synthesized iron oxide NPs conjugated to doxorubicin, to improve drug delivery for breast cancer treatment | [107] |

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA)-modified cerium-manganese oxide NPs | Methotrexate (anti-rheumatic) | Transdermal | Microneedle patch | Synthesis of BSA-modified cerium-manganese oxide NPs loaded with methotrexate and integrated into soluble hyaluronic acid-based microneedles, for targeting macrophages in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis | [108] | |

| Hybrid NPs | Phospholipid-calcium carbonate hybrid NPs/ lipids: soy lecithin, triglyceride monostearate | Tofacitinib citrate (Janus kinase inhibitor) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Design of phospholipid-coated amorphous calcium carbonate NPs for targeted delivery of tofacitinib citrate to hair follicles, for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia | [109] |

| Gold NPs conjugated lecithin-chitosan hybrid NPs | Tacrolimus (immunosuppressive, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory agent) | Topical | Suspension (NPs dispersion) | Conjugation of gold NPs with tacrolimus-loaded chitosan NPs or tacrolimus-loaded hybrid lecithin-chitosan NPs, as a promising drug delivery system for the treatment of psoriasis | [110] | |

| Lecithin/chitosan NPs | Pentoxifylline (anti-inflammatory drug) | Topical | Sponge (gel) | Development and characterization of lignocellulose nanocomposite sponge (hydrogel) incorporating pentoxifylline-loaded lecithin/chitosan NPs to control drug release for accelerated wound healing | [111] | |

| ZnO/Ag NPs (silver NPs dispersed in zinc oxide mesoporous microspheres), decorated with polycaprolactone-polyethylene glycol-polycaprolactone (PCL-PEG-PCL) nanomicelles | Methotrexate (immunosuppressive regulator, antipsoriatic) | Topical | Gel | Design and evaluation of multifunctional nanocomposite-based carbopol hydrogel comprising methotrexate-loaded ZnO/Ag NPs embellished with PCL-PEG-PCL nanomicelles to enhance therapeutic efficacy for psoriasis via synergistic combined therapy | [112] | |

| Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs/polyacrylonitrile electrospun nanofibers | Ibuprofen (NSAID) | Transdermal | System (electrospun nanofiber membrane) | Development and evaluation of dual-stimulus (pH and temperature) responsive transdermal drug delivery system containing ibuprofen-loaded ZnO NPs and polyacrylonitrile electrospun nanofiber membranes, aiming to achieve increased and sustained drug release | [113] |

| Active Ingredient (Therapeutic Class) | Proprietary Name (Marketing Status) | Dosage Form | Indication | Product Characteristics | Applicant | Approval Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asenapine (atypical antipsychotic) | Secuado® (Rx) | Transdermal system | Treatment of schizophrenia in adults | Description: translucent rounded square patch with a printed backing on one side and a release liner on the other; Excipients: alicyclic saturated hydrocarbon resin, butylated hydroxytoluene, isopropyl palmitate, maleate salts (monosodium maleate and disodium maleate), mineral oil, polyester film backing, polyisobutylene, silicone-treated polyester release liner, sodium acetate anhydrous, styrene-isoprene-styrene block copolymer; Duration of application: 24 h; Application site: hip, abdomen, upper arm, or upper back area | Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. (Saga, Japan) | 2019 (Patent expiration: 2033) |

| Buprenorphine (partial opioid agonist/antagonist) | Butrans® (Rx) | Film, extended release | Management of moderate to severe chronic pain in patients requiring a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic for an extended period of time | Description: rectangular transdermal system/patch, polymer matrix type (outer backing layer, adhesive film layer, foil layer between adhesive and drug/polymer adhesive matrix, peel-off release liner); Excipients: levulinic acid, oleyl oleate, povidone, polyacrylate cross-linked with aluminum; Duration of application: 7 days; Application site: upper outer arm, upper chest, upper back, or the side of the chest | Purdue Pharma L.P. (Stamford, CT, USA) | 2010, 2013, 2014 * |