Verification of the “Upward Variation in the Reporting Odds Ratio Scores” to Detect the Signals of Drug–Drug Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Targeted Drugs and Adverse Events

2.3. Statistical Models and Criteria

2.3.1. Ω Shrinkage Measure

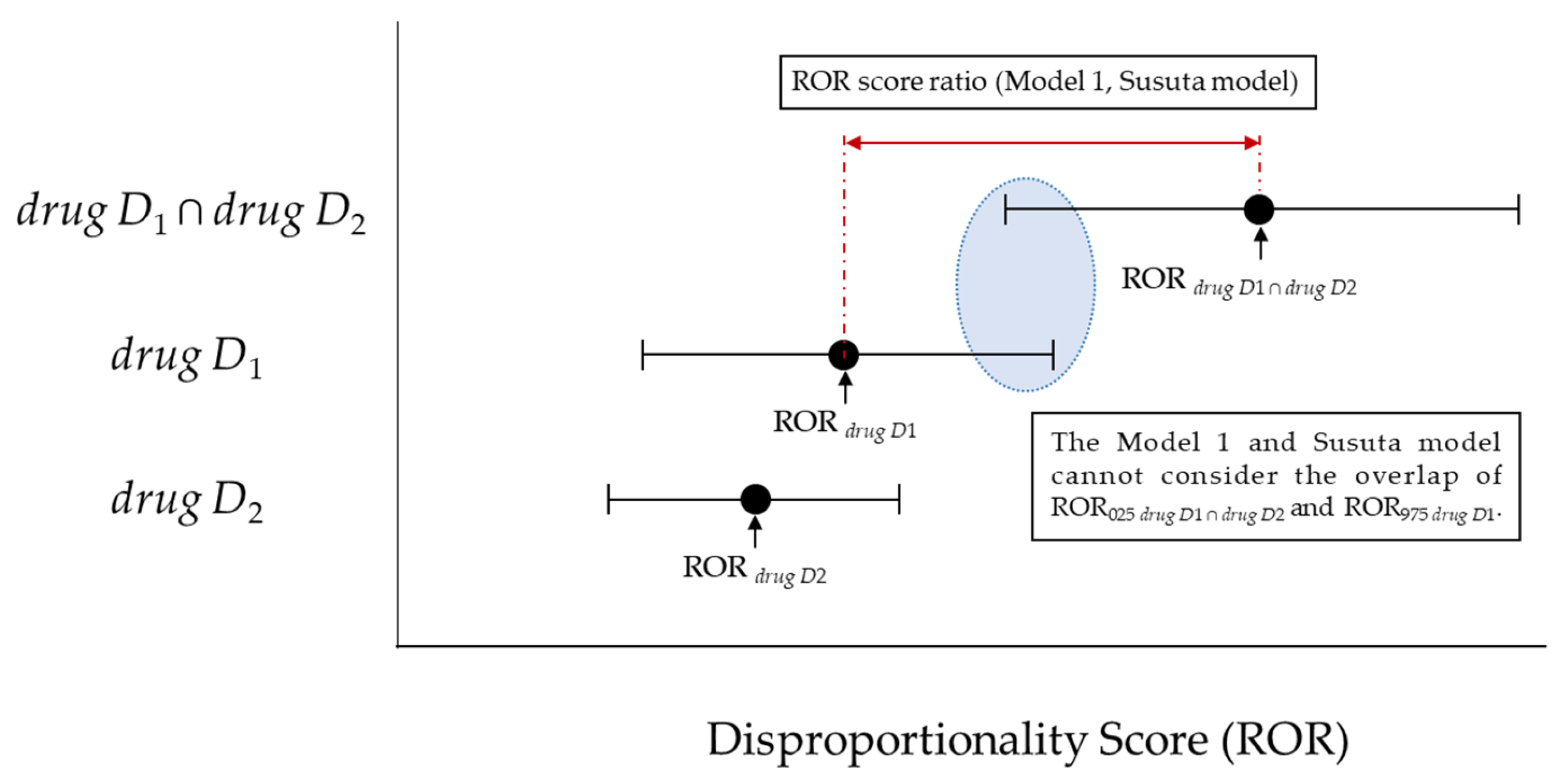

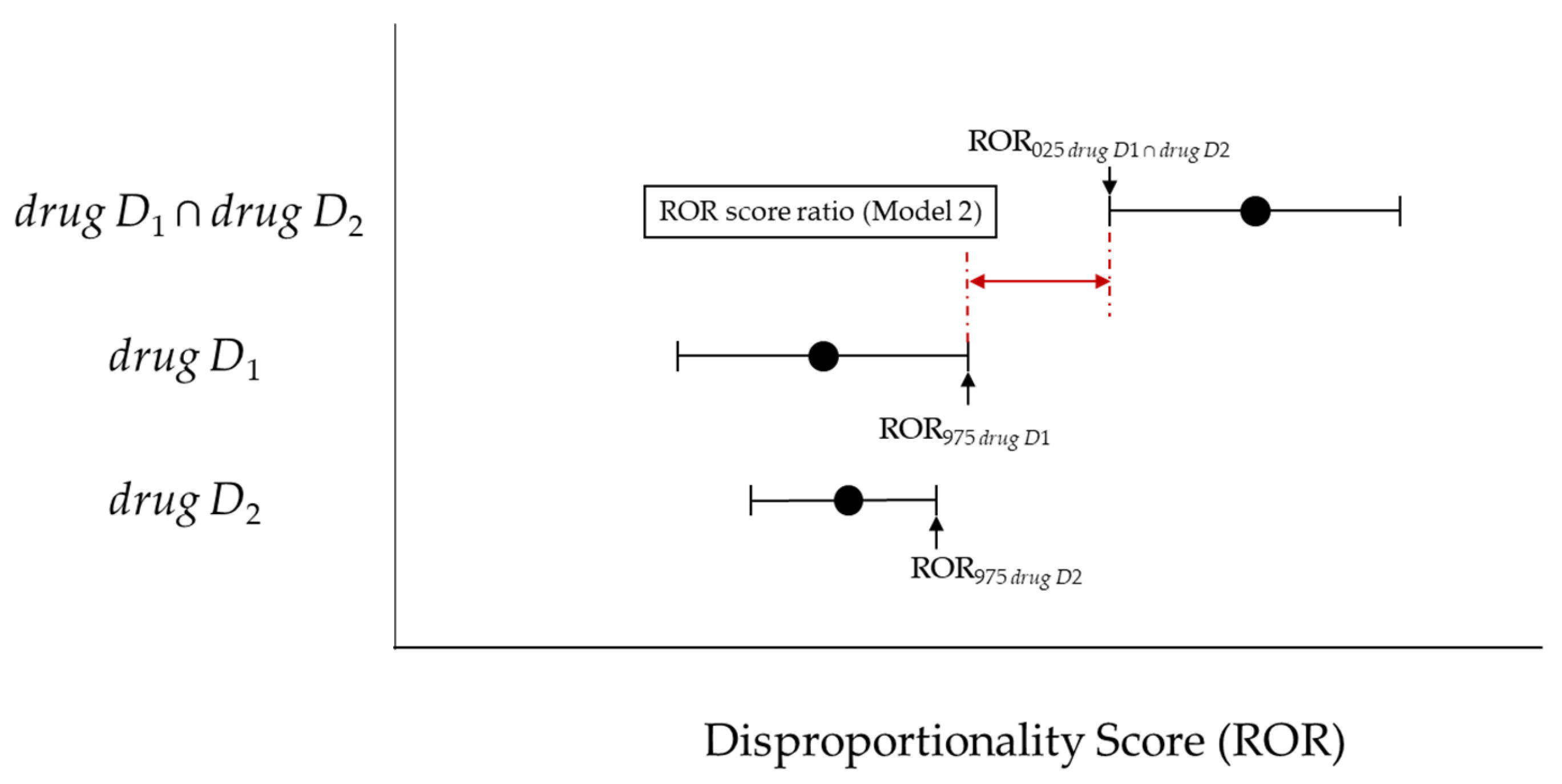

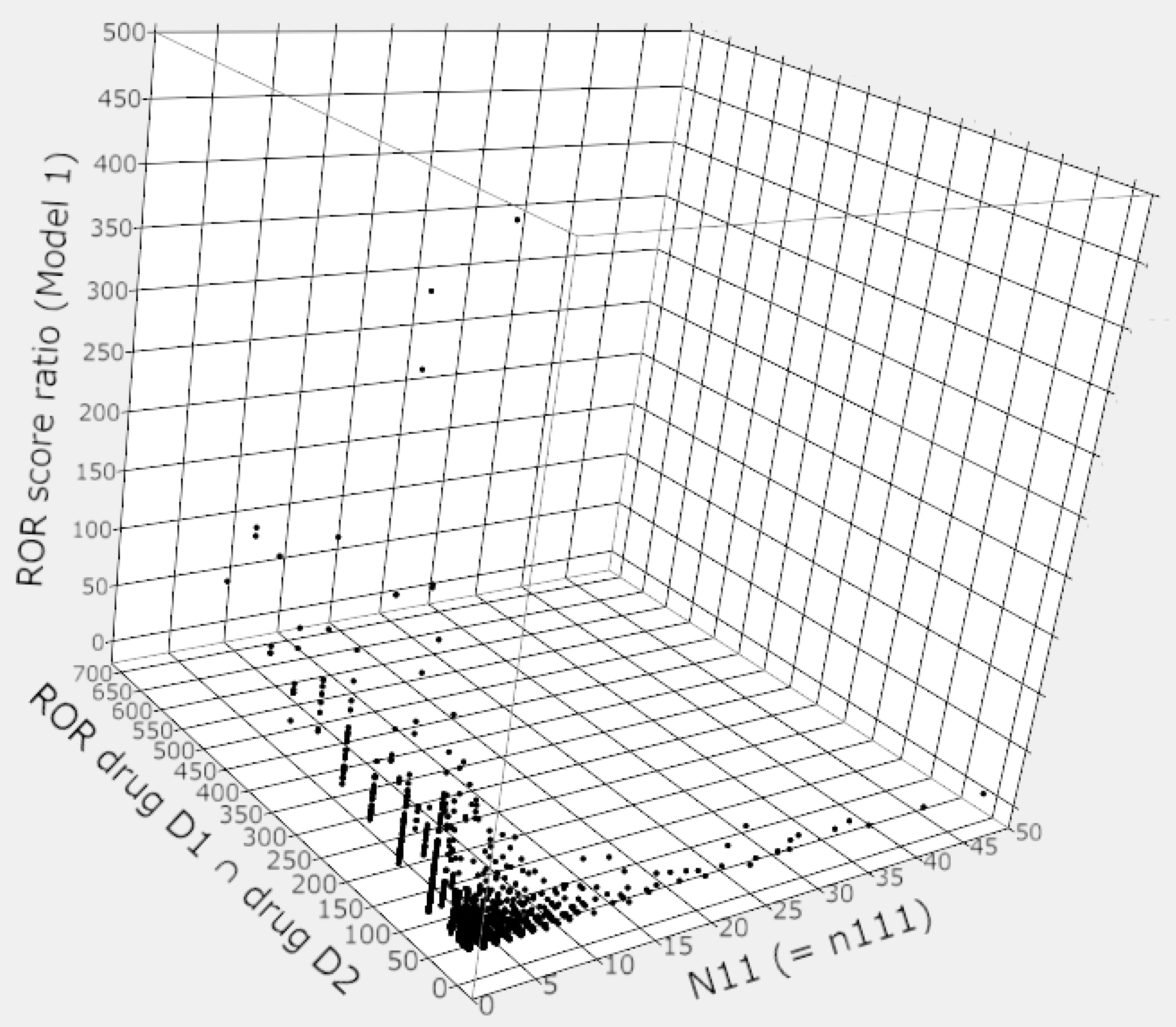

2.3.2. Upward Variation in Reporting Odds Ratio Scores

2.4. Targeted Drugs and Adverse Events

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iyer, S.V.; Harpaz, R.; LePendu, P.; Bauer-Mehren, A.; Shah, N.H. Mining clinical text for signals of adverse drug-drug interactions. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 2013, 21, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnjidic, D.; Hilmer, S.N.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Waite, L.; Seibel, M.J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Cumming, R.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Le Couteur, D.G. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, L.E.; Spiers, G.; Kingston, A.; Todd, A.; Adamson, J.; Hanratty, B. Adverse Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Older People: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugioka, M.; Tachi, T.; Mizui, T.; Koyama, A.; Murayama, A.; Katsuno, H.; Matsuyama, T.; Aoyama, S.; Osawa, T.; Noguchi, Y.; et al. Effects of the number of drugs used on the prevalence of adverse drug reactions in children. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, R.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, D. Influencing factors and their relationships of risk perception and decision-making behaviour of polypharmacy in patients with chronic diseases: A qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uragami, Y.; Takikawa, K.; Kareki, H.; Kimura, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Iihara, N. Effect of number of medications and use of potentially inappropriate medications on frailty among early-stage older outpatients. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, Y.; Esaki, H.; Murayama, A.; Sugioka, M.; Koyama, A.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Association between dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor and aspiration pneumonia: Disproportionality analysis using the spontaneous reporting system in Japan. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, S.; Wakamoto, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakagawa, C.; Hosomi, K.; Takada, M. Association between Antipsychotics and Osteoporosis Based on Real-World Data. Ann. Pharmacother. 2020, 54, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Otsubo, M.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Differences in detected safety signals between benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics: Pharmacovigilance study using a spontaneous reporting system. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, Y.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Detection algorithms and attentive points of safety signal using the spontaneous reporting systems as a clinical data source. Brief. Bioinform. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, S.; Friedman, C.; Hripcsak, G. Detection of drug-drug interactions through data mining studies using clinical sources, scientific literature and social media. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, Y.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Review of Statistical Methodologies for Detecting Drug-Drug Interactions Using Spontaneous Reporting Systems. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noren, G.N.; Sundberg, R.; Bate, A.; Edwards, I.R. A statistical methodology for drug-drug interaction surveillance. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 3057–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC). The UMC Measures of Disproportionate Reporting. Available online: https://www.who-umc.org/media/164041/measures-of-disproportionate-reporting_2016.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Hult, S.; Sartori, D.; Bergvall, T.; Hedfors Vidlin, S.; Grundmark, B.; Ellenius, J.; Norén, G.N. A Feasibility Study of Drug-Drug Interaction Signal Detection in Regular Pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2020, 43, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, Y.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Comparison of signal detection algorithms based on frequency statistical model for drug-drug interaction using spontaneous reporting systems. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, Y.; Takaoka, M.; Hayashi, T.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Antiepileptic combination therapy with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Analysis of a Japanese pharmacovigilance database. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susuta, Y.; Takahashi, Y. Safety risk evaluation methodology in detecting the medicine concomitant use risk which might cause critical drug rash. Jpn. J. Pharmacoepidemiol. 2014, 19, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asakura, M.; Yamaori, S. Analyses of Risk for Liver Injury Associated with Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and of Influence of Co-administered Drugs on Vildagliptin-induced Liver Injury Using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) Database. Jpn. J. Pharm. Diabet. 2020, 9, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, S.; Ishihara, Y.; Echizen, H. Detection of Signals of Convulsion-inducing Effect for Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics Alone and with Co-administration of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in Association with Aging Using Japanese Adverse Drug Event Reporting Database. Jpn. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonazzo, I.C.; Poluzzi, E.; Forcesi, E.; Salvo, F.; Pariente, A.; Marchesini, G.; De Ponti, F.; Raschi, E. Myopathy with DPP-4 inhibitors and statins in the real world: Investigating the likelihood of drug-drug interactions through the FDA adverse event reporting system. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, O.; Rathmann, W. A missed protective drug-drug interaction of DPP-4 inhibitors and statins on myopathy risk. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Bate, A.; Leufkens, H.G.M.; Lindquist, M.; Orre, R.; Egberts, A.C.G. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2002, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, K.; Koide, D.; Hirai, T. Comparison of data mining methodologies using Japanese spontaneous reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2004, 13, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, Y.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Subset Analysis for Screening Drug-Drug Interaction Signal Using Pharmacovigilance Database. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, Y.; Aoyama, K.; Kubo, S.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Improved Detection Criteria for Detecting Drug-Drug Interaction Signals Using the Proportional Reporting Ratio. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Yuen, N.A.; Ilic, K.; Miller, R.T.; Reese, M.J.; Brown, H.R.; Ambroso, J.I.; Falls, J.G.; Hunt, C.M. Comedications alter drug-induced liver injury reporting frequency: Data mining in the WHO VigiBase™. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, N.E. Odds ratio estimators when the data are sparse. Biometrika 1981, 68, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, R. Small sample confidence intervals for the odds ratio. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2004, 33, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.R. Evaluating concordances. In Principles of Medical Statistics; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 407–436. [Google Scholar]

- Gosho, M.; Maruo, K.; Tada, K.; Hirakawa, A. Utilization of chi-square statistics for screening adverse drug-drug interactions in spontaneous reporting systems. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 73, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarfman, A.; Machado, S.G.; O’Neill, R.T. Use of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDA’s spontaneous reports database. Drug Saf. 2002, 25, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Matsushita, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Maeda, T.; Nukui, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Sawa, J.; Maeda, H. Early Detection of Important Safety Information -Recent Methods for Signal Detection. Jpn. J. Biomet. 2004, 25, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, A.; Lindquist, M.; Edwards, I.R.; Olsson, S.; Orre, R.; Lansner, A.; De Freitas, R.M. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 54, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuMouchel, W. Bayesian Data Mining in Large Frequency Tables, with an Application to the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System. Am. Stat. 1999, 53, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T. Signal Detection of Adverse Drug Reactions. Jpn. J. Pharmacoepidemiol. 2009, 14, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urushihara, H. Basic Dos and Don’ts in Applying Signal Detection Methods to Spontaneous Reporting Systems Databases. Jpn. J. Drug Inform. 2019, 21, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Epidemiology of adverse reactions to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Adv. Inflamm. Res. 1984, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pariente, A.; Gregoire, F.; Fourrier-Reglat, A.; Haramburu, F.; Moore, N. Impact of safety alerts on measures of disproportionality in spontaneous reporting databases: The notoriety bias. Drug Saf. 2007, 30, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.W.; Hochberg, A.M.; Pearson, R.K.; Hauben, M. An experimental investigation of masking in the US FDA adverse event reporting system database. Drug Saf. 2010, 33, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target AE | Other AEs | Total | ||

| drug D1 and drug D2 | n111 | n110 | n11+ | |

| drug D1 without drug D2 | n101 | n100 | n10+ | |

| drug D2 without drug D1 | n011 | n010 | n01+ | |

| Neither drug D1 or drug D2 | n001 | n000 | n00+ | |

| Total | n++1 | n++0 | n+++ | |

| Target AE | Other AEs | Total | ||

| Target drug (s) | N11 | N12 | N1+ | |

| Other drugs | N21 | N22 | N2+ | |

| Total | N+1 | N+2 | N++ | |

| Ω Shrinkage Measure | Total | |||

| Yes | No | |||

| Target model | Yes | Nyy | Nyn | Ny. |

| No | Nny | Nnn | Nn. | |

| Total | N.y | N.n | N.. | |

| Statistical Models | Signal (Y/N) | Number (%) of Combinations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n111 < 3 | n111 = 3 | n111 = 4 | n111 = 5 | n111 > 5 | Total | ||

| Model 1 | Y | 1363 (47.8) | 243 (65.3) | 159 (66.8) | 110 (80.3) | 237 (72.3) | 2112 (53.8) |

| N | 525 (18.4) | 48 (12.9) | 23 (9.7) | 14 (10.2) | 42 (12.8) | 652 (16.6) | |

| N (no criterion) | 961 (33.7) | 81 (21.8) | 56 (23.5) | 13 (9.5) | 49 (14.9) | 1160 (29.6) | |

| Susuta model | Y | 1142 (40.1) | 207 (55.6) | 136 (57.1) | 97 (70.8) | 176 (53.7) | 1758 (44.8) |

| N | 746 (26.2) | 84 (22.6) | 46 (19.3) | 27 (19.7) | 103 (31.4) | 1006 (25.6) | |

| N (no criterion) | 961 (33.7) | 81 (21.8) | 56 (23.5) | 13 (9.5) | 49 (14.9) | 1160 (29.6) | |

| Model 2 | Y | 239 (8.4) | 106 (28.5) | 84 (35.3) | 74 (54.0) | 134 (40.9) | 637 (16.2) |

| N | 1649 (57.9) | 185 (49.7) | 98 (41.2) | 50 (36.5) | 145 (44.2) | 2127 (54.2) | |

| N (no criterion) | 961 (33.7) | 81 (21.8) | 56 (23.5) | 13 (9.5) | 49 (14.9) | 1160 (29.6) | |

| Corrected Model 2 | Y | 678 (23.8) | 178 (47.8) | 118 (49.6) | 92 (67.2) | 173 (52.7) | 1239 (31.6) |

| N | 2171 (76.2) | 194 (52.2) | 120 (50.4) | 45 (32.8) | 155 (47.3) | 2685 (68.4) | |

| N (no criterion) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total | 2849 | 372 | 238 | 137 | 328 | 3924 | |

| Model 1 | Susuta Model | Model 2 | Corrected Model 2 * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ω Shrinkage measure | κ: 0.074 95% CI: 0.058–0.089 Ppos: 0.325 Pneg: 0.621 | κ: 0.152 95% CI: 0.135–0.168 Ppos: 0.371 Pneg: 0.711 | κ: 0.495 95% CI: 0.475–0.514 Ppos: 0.581 Pneg: 0.913 | κ: 0.479 95% CI: 0.459–0.493 Ppos: 0.597 Pneg: 0.867 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noguchi, Y.; Yoshizawa, S.; Aoyama, K.; Kubo, S.; Tachi, T.; Teramachi, H. Verification of the “Upward Variation in the Reporting Odds Ratio Scores” to Detect the Signals of Drug–Drug Interactions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13101531

Noguchi Y, Yoshizawa S, Aoyama K, Kubo S, Tachi T, Teramachi H. Verification of the “Upward Variation in the Reporting Odds Ratio Scores” to Detect the Signals of Drug–Drug Interactions. Pharmaceutics. 2021; 13(10):1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13101531

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoguchi, Yoshihiro, Shunsuke Yoshizawa, Keisuke Aoyama, Satoaki Kubo, Tomoya Tachi, and Hitomi Teramachi. 2021. "Verification of the “Upward Variation in the Reporting Odds Ratio Scores” to Detect the Signals of Drug–Drug Interactions" Pharmaceutics 13, no. 10: 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13101531

APA StyleNoguchi, Y., Yoshizawa, S., Aoyama, K., Kubo, S., Tachi, T., & Teramachi, H. (2021). Verification of the “Upward Variation in the Reporting Odds Ratio Scores” to Detect the Signals of Drug–Drug Interactions. Pharmaceutics, 13(10), 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13101531