Abstract

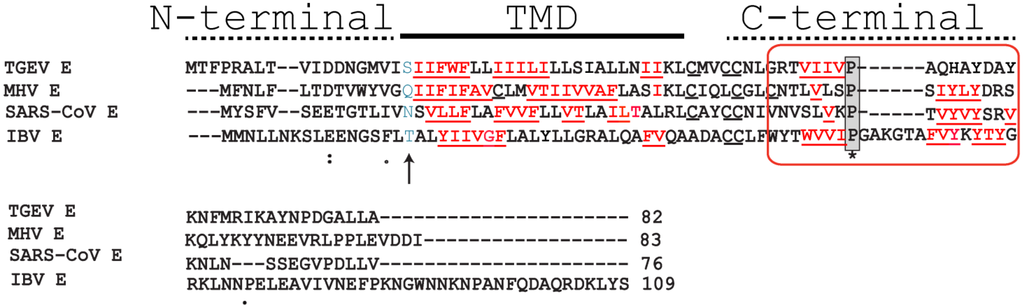

Viroporins are members of a rapidly growing family of channel-forming small polypeptides found in viruses. The present review will be focused on recent structural and protein-protein interaction information involving two viroporins found in enveloped viruses that target the respiratory tract; (i) the envelope protein in coronaviruses and (ii) the small hydrophobic protein in paramyxoviruses. Deletion of these two viroporins leads to viral attenuation in vivo, whereas data from cell culture shows involvement in the regulation of stress and inflammation. The channel activity and structure of some representative members of these viroporins have been recently characterized in some detail. In addition, searches for protein-protein interactions using yeast-two hybrid techniques have shed light on possible functional roles for their exposed cytoplasmic domains. A deeper analysis of these interactions should not only provide a more complete overview of the multiple functions of these viroporins, but also suggest novel strategies that target protein-protein interactions as much needed antivirals. These should complement current efforts to block viroporin channel activity.

2. The Small Hydrophobic (SH) Protein in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

2.1. The Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) is an enveloped pneumovirus in the Paramyxoviridae family. hRSV was first isolated in 1956 from a chimpanzee with a respiratory illness, and later found to be a human virus [102]. hRSV is the leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants and elderly [103], and the most frequent cause of hospitalization of infants and young children in industrialized countries. In the general population, hospitalization rates are similar to those found for influenza infections [104].

In developing countries, RSV is a significant cause of death, with global estimates of more than 70,000 deaths in young children. hRSV is the third most important cause of deadly childhood pneumonia after Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae [105]. The epithelial cells of the respiratory tract are the major sites of virus replication, but hRSV can infect a wide variety of human and animal cells.

The fusion (F) protein facilitates viral entry through the cell membrane [106] through formation of a 6-helix bundle. This critical step has been targeted in vitro, e.g., peptides that mimic conserved domains of RSV-F protein [107,108], peptides based on F-interacting RhoA GTPase [109], dendrimer-like molecule RFI-641 [110], or other organic compounds [111,112]. Other approaches have involved gene transfer to expose viral proteins to cells [113], or siRNA against specific viral proteins [114]. Vaccines have been recently designed based on a stabilized RSV-F form which preserves a highly antigenic site in its prefusion state, yielding RSV-specific neutralizing antibodies in mice and macaques [115,116]. Recently, a vaccine candidate based on the extracellular domain (C-terminal) of RSV viroporin, the small hydrophobic (SH) protein, has been reported [117], and prevention of nasopulmonary infection in mice caused by RSV has been reported using stapled peptides targeting the fusogenic F-protein 6-helix bundle [118]. However, despite all these efforts, new FDA-approved drugs have yet to emerge.

Palivizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG) directed against F protein but is only moderately effective [119], which combined with its high cost [120] limits its use to a small fraction of patients worldwide. The only licensed drug for use in infected individuals is ribavirin, a nucleoside analog, but its efficacy is very limited [121]. Naturally acquired immunity to RSV is neither complete nor durable, and recurrent infections occur frequently during the first three years of life. Therefore, low immunoprotection and lack of suitable antivirals makes imperative the search of new drug targets and strategies for effective treatment. The hRSV genome transcribes 11 proteins [122], including the three membrane proteins: fusion (F), small hydrophobic (SH), and attachment (G), which plays a role in the initial interaction of the virus with the cell [123,124].

2.2. The Small Hydrophobic Protein

The small hydrophobic (SH) protein is 64 (RSV subgroup A) or 65 (RSV subgroup B) amino acids long, with a single α-helical TM domain [125,126]. Both A and B subgroups are capable of inducing severe lower respiratory tract disease in humans [127,128,129]. Most SH protein accumulates at the membranes of the Golgi complex in infected cells, but it has also been detected in the endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membranes [130].

RSV that lacks SH (RSVΔSH) is still viable, and still forms syncytia [131,132,133], but it is attenuated in vivo. In mouse, RSV ΔSH replicated 10-fold less efficiently in the upper respiratory tract [132], whereas chimpanzees developed significantly less rhinorrhea than those infected with wild-type RSV [134]. Other reports have shown that lack of SH protein leads to an attenuated phenotype in children and in rats [133,135]. Overall, these results indicate involvement of hRSV SH protein in replication and pathogenesis. In fact, a recombinant RSV with deletion of the SH gene has been proposed as a live vaccine in calves [136] and in humans [133].

In common to SARS-CoV E protein, SH protein blocks or delays apoptosis in infected cells [137], and a similar anti-apoptotic effect of SH protein has been observed for other members of the Paramyxoviridae family that encode SH proteins, e.g., J Paramyxovirus (JPV) [138,139], mumps virus (MuV), and the parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5), formerly known as simian virus 5 (SV5)–see below. In all these systems, SH protein seems to block apoptosis during infection through inhibition of the TNF-α pathway [137,138,140,141]. For example, apoptosis induced by PIV5 ΔSH was blocked by neutralizing antibodies against TNF-α and TNF-α receptor 1 (TNF-R1), but not by an antibody against TNF-R2 [140]. In addition, when the SH protein gene of PIV5 was substituted by SH protein from MuV or RSV (A2 or B1 strains) [137,141], apoptosis was prevented through blockage of the TNFα-mediated NF-κB pathway, suggesting that these SH proteins target similar pathways but through unknown mechanisms. By delaying apoptosis, the virus may evade the premature death of host cells, allowing viral replication.

Viruses are able to activate the inflammasome, which activates caspase-1 to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., IL-1β. They do so by disrupting ion homeostasis through the expression of viroporins, which allow ion leakage from intracellular organelles into the cytosol. For example, influenza A virus (IAV) activates NLRP3 as a result of H+ or ion flux from Golgi mediated by the M2 ion channel [142]. The 2B protein from several picornaviruses, including the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), poliovirus and enterovirus 71 were shown to induce NLRP3 cytoplasmic relocalization and inflammasome activation in an intracellular Ca2+-mediated manner [143]. The channel activity of SARS-CoV E protein is required for the processing of IL-1β [34], which requires caspase-1 activation. Channel activity of SH protein may also result directly or indirectly in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Results consistent with this have been reported [144], where hRSV infection led to cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines, producing IL-1β and causing lung pathology and disease exacerbation. Further, an hRSV ΔSH mutant led to reduced IL-1β secretion and caspase-1 expression, whereas lipid raft disruptors, which may affect SH protein targeting to Golgi lipid rafts, blocked inflammasome activation [145]. Similar effects were observed by blocking SH protein channel activity [145]. However, the drugs used were not specific or particularly effective. Therefore, although a suggestion has been made to link inflammasome activation to SH protein channel activity and ion leakage from the Golgi during infection [145], this has not been confirmed.

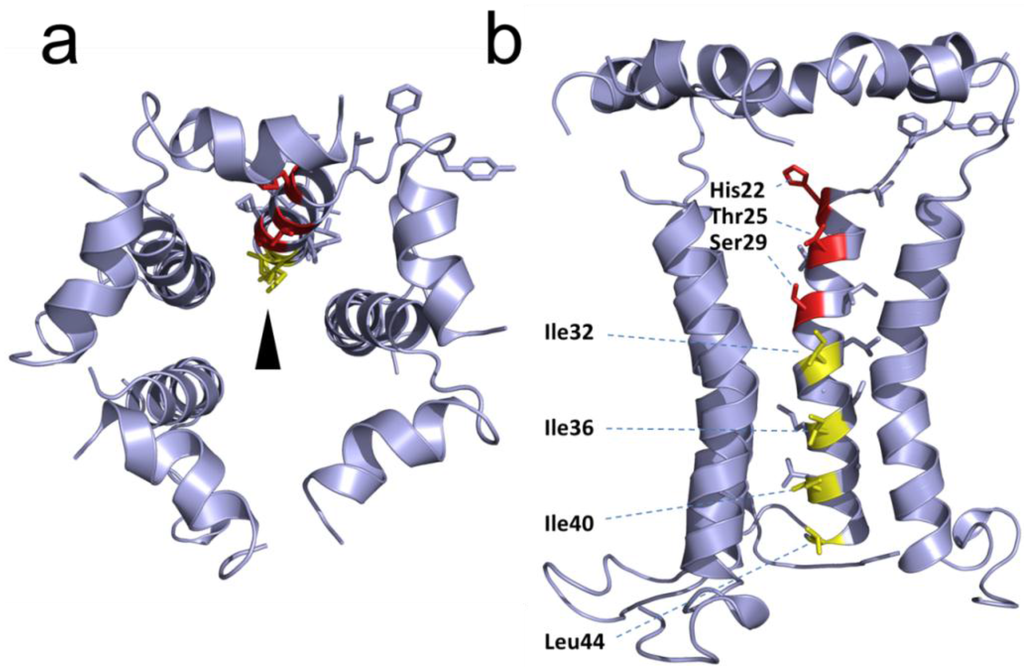

2.3. Structural Studies and Relevant Domains of RSV SH Protein

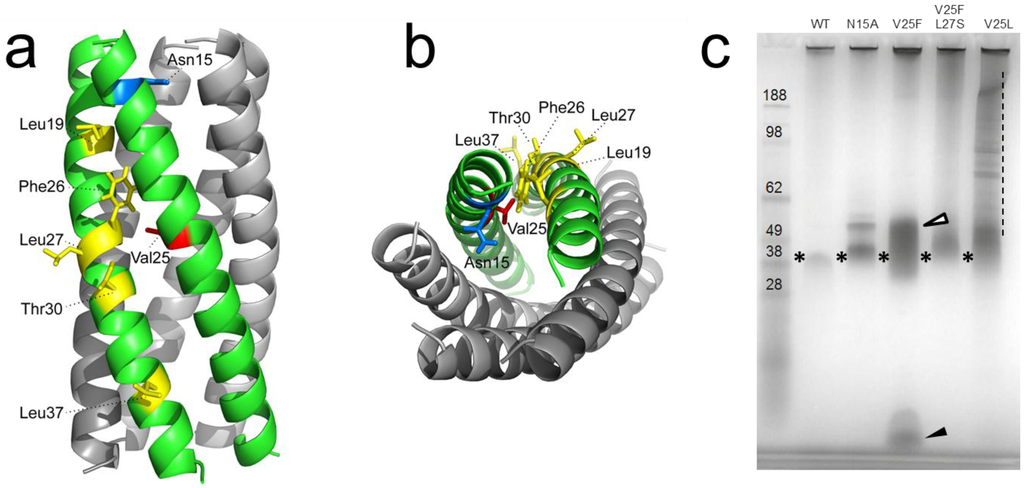

The topology of RSV SH protein is just opposite to that of CoV E proteins, with N- and C-terminal extramembrane domains oriented cytoplasmically and lumenally/extracellularly, respectively. The mutual orientation of the transmembrane (TM) α-helices that form the ion channel was determined in lipid bilayers using site specific infrared dichroism [146,147]. A description of the full length SH protein monomer has been obtained by solution NMR in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles [126] and in bicelles [148]. Like SARS-CoV E, SH protein forms homopentameric channels [126,146] that have low ion selectivity [148]. The TM domain of SH protein has a funnel-like architecture [126] (Figure 4), as observed in other viroporins, e.g., influenza M2 [149], SARS E protein [46] and HCV p7 [150]. A narrower region [126] in the TM domain is lined with hydrophobic side chains (Ile32, Ile36, Ile40 and Leu44) whereas the more open N-terminal region is lined by polar residues, i.e., His22, Thr25 and Ser29 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Structural model of RSV SH protein. Top view (a) and side view (b) of the SH protein pentamer [148]. In the latter, one monomer has been removed. The lumenally oriented polar residues (red) and hydrophobic residues (yellow) in the α-helical bundle are indicated.

In RSV SH protein, the TM α-helix extends up to His-51 in the C-terminal region, followed by a loop, whereas the N-terminal cytoplasmic extramembrane domain forms a short α-helix (residues 5–14) (Figure 4b), which is present both in micelles and in bicelles [148].

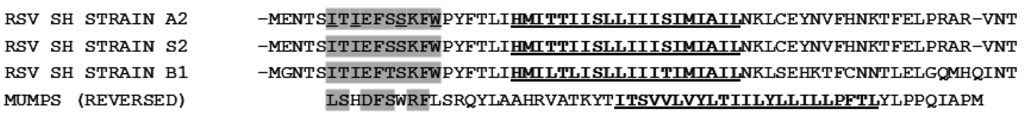

Several indications suggest the involvement of this exposed cytoplasmic (N-terminal) tail in the observed anti-apoptotic effects of SH protein (see above). For example, addition of a hemagglutinin antigen epitope tag at the cytoplasmic tail of PIV5 SH protein abolished its ability to inhibit TNF-α signaling [141]. Second, while the SH proteins of RSV and MuV (both human pathogens) have opposite topologies, they share a high degree of similarity in a 10-residue stretch at the cytoplasmic domain (N-terminus for RSV SH and C-terminus for MuV SH) (Figure 5). Third, SH proteins in MuV, PIV5 and JPV have extremely short lumenal domains (9, 2 and 10 residues, respectively) compared with their much longer cytoplasmic domains. Finally, hRSV SH protein sequence is most conserved at the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain [151,152,153].

Figure 5.

Alignment between SH protein for strains A2 and S2 (group A), B1 (group B) and MuV. Note that MuV SH is a type I integral membrane protein, i.e., its C terminus faces the cytoplasm [154,155], therefore its orientation has been reversed for the alignment. The TM domain is underlined and bold, and a “10-residue” conserved fragment of high similarity has been highlighted in grey.

2.4. Protein-Protein Interactions Involving hRSV SH Protein

The interaction between RSV SH and G proteins has been reported previously in infected cells [156,157], although its significance is not yet clear. F protein seems to be the main determinant of host cell specificity during virus entry [158], and both F and G proteins are able to bind heparin sulfate, the putative cell receptor for RSV [159]. However, a tri-component complex between SH, G and F proteins was not observed [156]. Both G and F proteins have one predicted TM domain, and interaction with SH protein can be both through the TM domain or extramembrane domains of the latter.

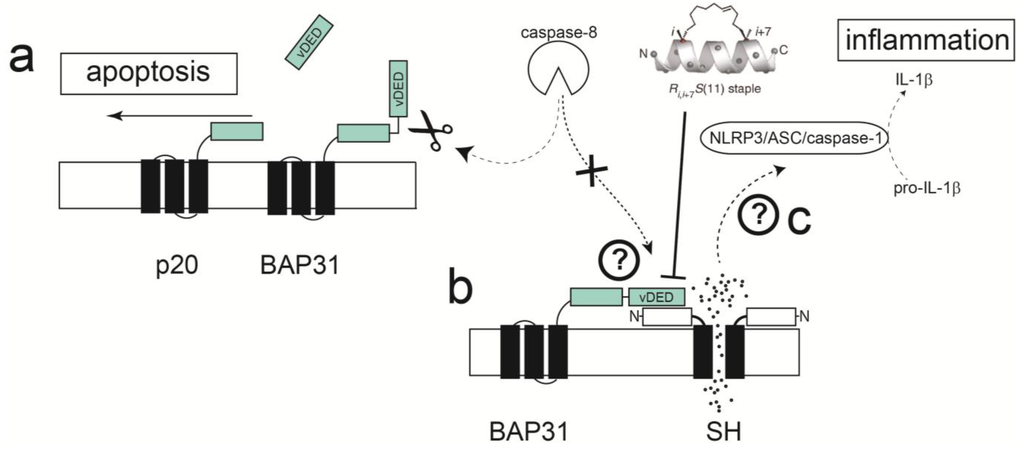

Recently, a membrane-based yeast two-hybrid system (MbY2H) was used to identify a cellular binding partner of hRSV SH protein, the B-Cell receptor-associated protein 31 (BAP31) [160], in a human lung cDNA library. BAP31 is a membrane protein located at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and has an essential role in sorting newly synthesized membrane proteins [161]. Additionally, BAP31 has a cytoplasmic C-terminus that form two coiled coils [162,163], one of them containing a variant of the death effector domain (vDED) [164] flanked by two caspase-8 cleavage sites. This domain is excised upon activation of caspase-8 [165,166] to produce a fragment p20, known to function as a proapoptotic factor [166,167]. BAP31 also forms a complex with the mitochondrial fission 1 (Fis1) [168] membrane protein, which spans the ER and mitochondria, and serves as a platform for activation of caspase-8. The consequences, or biological relevance, of the interaction between SH and BAP31 proteins are not known. These contacts may interfere between BAP31 and caspase-8 interaction, e.g., by SH protein binding to BAP31 vDED domain. This could in turn prevent the cleavage of BAP31 and the formation of pro-apoptotic p20, thus delaying apoptosis (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic depicting a hypothetical model for apoptosis delay through interaction of SH and BAP31 proteins. (a) Activation of caspase 8 via TNF-α or other effectors cleaves the cytoplasmic vDED domain of BAP31, producing pro-apoptotic p20; (b) SH protein may bind to various proteins in this pathway, e.g., BAP31, blocking its cleavage by caspase-8; (c) ion channel activity through SH protein may contribute to production of IL-1β through activation of the inflammasome.

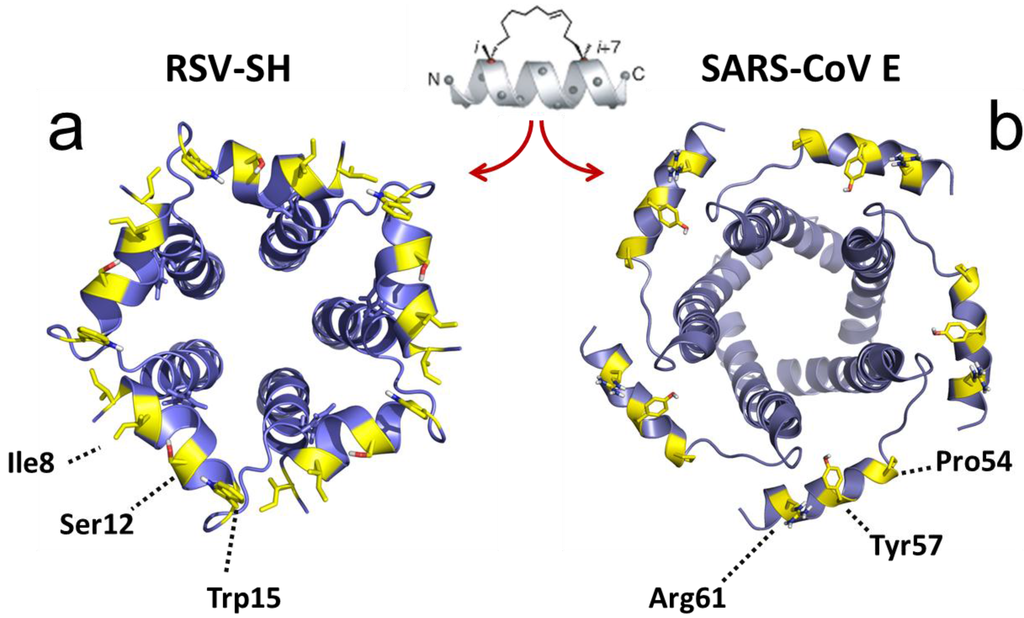

The screening for SH protein binders referred to above [160] used a truncated form of SH protein, encompassing only the TM domain and the cytoplasmic domain (M1-L44), therefore only these domains are involved in interaction with BAP31. In the latter report, a stretch of residues in the N-terminal cytoplasmic helix of SH protein was perturbed by addition of the BAP31 vDED domain to full length SH protein in micelles, with major shifts observed at residues Ile6, Ile8, Ser12 and Trp15 (Figure 7a). Although there is conservation in that region between hRSV SH and mumps virus SH protein (Figure 5), the residues indicated above are not conserved, whereas PIV5 SH protein does not show any homology in this region, suggesting that the latter do not bind BAP31, or they do but through a different binding site.

A system with intriguing similarities to RSV SH protein is found in the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16). Indeed, apoptosis induced by Fas ligand (FasL) or by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) was strongly suppressed in keratinocytes expressing E5 [169], a viroporin also found to bind BAP31 [170]. E5 impaired formation of the death-inducing signaling complex triggered by TRAIL, showing that inhibition of ligand-mediated apoptosis in human keratinocytes is a primary function of the HPV-16 E5 protein.

The mechanism of inhibition of TNF-α signaling by SH proteins is not clear, but a model has been proposed [141] where SH protein interacts directly or indirectly with TNF-R1, blocks TNF-α signaling, and prevents more TNF-α from being produced. To elucidate this mechanism it is very important to identify other RSV SH-interacting proteins that may be involved in apoptotic pathways. In addition, to unequivocally link SH protein ion channel activity to inflammasome activation, channel inactive mutants need to be tested. Obvious candidates are polar residues that face the lumen of the channel (Figure 4b), e.g., mutations H22A, T25A and S29A, and mutants that disrupt channel structure, i.e., obtained by introducing bulky side chains in residues involved in TM helix-helix interactions.

2.5. Disruption of Protein-Protein Interactions; Potential for Clinically Relevant Strategies

Despite the fact that the precise mechanisms that link the viroporins E and SH with the delaying of apoptosis or triggering the inflammasome are not known, it is clear that novel strategies to combat viral infection can already be hypothesized.

For example, if the model shown in Figure 6 is confirmed, one can envisage the possibility that stapled peptides mimicking the α-helical cytoplasmic domain of SH protein can disrupt the interactions between SH-vDED, leading to enhanced apoptosis and cell death. Stapled α-helical peptides have two special amino acids bearing an olefinic side chain [171]. Prior to the final FMOC-deprotection step, the peptide-resin is subjected to ring-closing olefin metathesis (i.e., stapling) which increases peptide stability and helicity. In principle, both membrane and extramembrane parts of proteins can be targeted, as shown recently for Halobacterium salinarium where efflux by a small multidrug resistance protein was inhibited with peptides targeting its TM domain [172]. In this case, peptides that disrupt monomer-monomer interaction in viroporins, and hence abolish channel activity, are still unexplored.

Figure 7.

RSV SH and SARS-CoV E protein channels. (a) RSV SH protein channel and (b) SARS-CoV E protein channel, viewed from the cytoplasmic side [126,148]. The residues exposed to the cytoplasmic side (yellow) may be actively involved in protein-protein interactions and these cytoplasmic α-helices can be used as templates for stapled α-helical peptides.

Once defined the interactions between the SARS-CoV E protein C-terminal tail and other cellular or viral binders, e.g., between E and M, a similar strategy could be followed by designing α-helical peptides that mimic the cytoplasmically exposed α-helical domain in the C-terminal tail of CoV E proteins (Figure 7b).

To conclude, both SARS-CoV E and RSV SH viroporins delay apoptosis in infected cells, which may help evade host inflammatory responses and the premature death of the host cells. This effect may be related to a common cytoplasmically oriented membrane-bound α-helix, connected to the TM domain by a flexible loop. It is becoming apparent that these cytoplasmically oriented α-helices can become templates for the design of stapled α-helical peptides that would disrupt protein-protein interactions with viral and host proteins, and these interactions potentially constitute novel drug targets to combat viral infection. However, more detailed mechanistic information should be available before these strategies can be widely used.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by Tier 1 grant RG 51/13 (J.T.)

Author Contributions

J.T wrote the manuscript, W.S. and L.Y. contributed materials, L.D.X. wrote minor parts and read critically the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Enjuanes, L.; Brian, D.; Cavanagh, D.; Holmes, K.; Lai, M.M.C.; Laude, H.; Masters, P.; Rottier, P.; Siddell, S.G.; Spaan, W.J.M.; et al. Coronaviridae. In Virus taxonomy. Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses; van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Fauquet, C.M., Bishop, D.H.L., Carsten, E.B., Estes, M.K., Lemon, S.M., McGeoch, D.J., Maniloff, J., Mayo, M.A., Pringle, C.R., et al., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 835–849. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Huang, Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Coronavirus Diversity, Phylogeny and Interspecies Jumping. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 234, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, R.J.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.; Enjuanes, L.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Holmes, K.V.; Perlman, S.; Poon, L.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Talbot, P.J.; et al. Family Coronaviridae. In Virus Taxonomy, Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; King, A.M.Q., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B., Lefkowitz, E.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 29, 806–828. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudette, F.R.; Hudson, C.B. Cultivation of the virus of infectious bronchitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1937, 90, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell, D.A.; Bynoe, M.L. Cultivation of a novel type of common cold virus in organ cultures. Br. Med. J. 1965, 1, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.V. SARS coronavirus: A new challenge for prevention and therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, V.S.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Haagmans, B.L. MERS: Emergence of a novel human coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 5, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Rao, Z. Current progress in antiviral strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilianski, A.; Baker, S.C. Cell-based antiviral screening against coronaviruses: Developing virus-specific and broad-spectrum inhibitors. Antivir. Res. 2014, 101, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilianski, A.; Mielech, A.M.; Deng, X.; Baker, S.C. Assessing activity and inhibition of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like and 3C-like proteases using luciferase-based biosensors. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 11955–11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.L.; Becker, M.M.; Eckerle, L.D.; Bolles, M.; Denison, M.R.; Baric, R.S. A live, impaired-fidelity coronavirus vaccine protects in an aged, immunocompromised mouse model of lethal disease. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjuanes, L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; DeDiego, M.L. Recombinant Live Vaccines to Protect against the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. In Replicating Vaccines, Birkhauser Advances in Infectious Diseases; Dormitzer, P., Mandl, C.W., Rappuoli, R., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Heald-Sargent, T.; Gallagher, T. Ready, set, fuse! The coronavirus spike protein and acquisition of fusion competence. Viruses 2012, 4, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 66, 193–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.X.; Fung, T.S.; Chong, K.; Shukla, A.; Hilgenfeld, R. Accessory proteins of SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.X.; Cavanagh, D.; Green, P.; Inglis, S.C. A Polycistronic Messenger-RNA Specified by the Coronavirus Infectious-Bronchitis Virus. Virology 1991, 184, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, M.; L’Haridon, R.; Vautherot, J.-F.; Laude, H. TGEV corona virus ORF4 encodes a membrane protein that is incorporated into virions. Virology 1992, 188, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Bi, W.; Weiss, S.R.; Leibowitz, J.L. Mouse hepatitis virus gene 5b protein is a new virion envelope protein. Virology 1994, 202, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Torres, J.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Biochemical and functional characterization of the membrane association and membrane permeabilizing activity of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. Virology 2006, 349, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corse, E.; Machamer, C.E. Infectious bronchitis virus E protein is targeted to the Golgi complex and directs release of virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4319–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.X.; Inglis, S.C. Association of the infectious bronchitis virus 3c protein with the virion envelope. Virology 1991, 185, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.Y.T.; Abraham, S.; Sethna, M.; Hung, S.-L.; Sethna, P.; Hogue, B.G.; Brian, D.A. The 9-kDa hydrophobic protein encoded at the 3′ end of the porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus genome is membrane-associated. Virology 1992, 186, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corse, E.; Machamer, C.E. The cytoplasmic tails of infectious bronchitis virus E and M proteins mediate their interaction. Virology 2003, 312, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raamsman, M.J.B.; Krijnse Locker, J.; de Hooge, A.; de Vries, A.A.F.; Griffiths, G.; Vennema, H.; Rottier, P.J.M. Characterization of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 small membrane protein E. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.A.; Riffle, A.J.; Pike, S.L.; Gardner, D.; Hogue, B.G. Importance of conserved cysteine residues in the coronavirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3000–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Alvarez, E.; Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Llorente, M.; Kremer, L.; Shuo, S.; Enjuanes, L. Subcellular location and topology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. Virology 2011, 415, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.X.; Yuan, Q.; Liao, Y. Coronavirus envelope protein: A small membrane protein with multiple functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeDiego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Alvarez, E.; Oliveros, J.C.; Zhao, J.; Fett, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein regulates cell stress response and apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeDiego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Fett, C.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L. Inhibition of NF-κB-mediated inflammation in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-infected mice increases survival. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamirande, E.W.; DeDiego, M.L.; Roberts, A.; Jackson, J.P.; Alvarez, E.; Sheahan, T.; Shieh, W.J.; Zaki, S.R.; Baric, R.; Enjuanes, L.; et al. A live attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is immunogenic and efficacious in golden Syrian hamsters. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 7721–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netland, J.; DeDiego, M.L.; Zhao, J.; Fett, C.; Alvarez, E.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Enjuanes, L.; Perlman, S. Immunization with an attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus deleted in E protein protects against lethal respiratory disease. Virology 2010, 399, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazán, F.; DeDiego, M.L.; Sola, I.; Zuñiga, S.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Marquez-Jurado, S.; Andrés, G.; Enjuanes, L. Engineering a Replication-Competent, Propagation-Defective Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as a Vaccine Candidate. MBio 2013, 4, e00650-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regla-Nava, J.A.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Fett, C.; Castaño-Rodríguez, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L.; de Diego, M.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses with mutations in the E protein are attenuated and promising vaccine candidates. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3870–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Dediego, M.L.; Verdia-Baguena, C.; Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castano-Rodriguez, C.; Alcaraz, A.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel activity promotes virus fitness and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruch, T.R.; Machamer, C.E. A single polar residue and distinct membrane topologies impact the function of the infectious bronchitis coronavirus E protein. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruch, T.R.; Machamer, C.E. The hydrophobic domain of infectious bronchitis virus E protein alters the host secretory pathway and is important for release of infectious virus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavi, E.; Wang, Q.; Weiss, S.R.; Gonatas, N.K. Syncytia formation induced by coronavirus infection is associated with fragmentation and rearrangement of the Golgi apparatus. Virology 1996, 221, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulasli, M.; Verheije, M.H.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Reggiori, F. Qualitative and quantitative ultrastructural analysis of the membrane rearrangements induced by coronavirus. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 844–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruch, T.R.; Machamer, C.E. The coronavirus E protein: Assembly and beyond. Viruses 2012, 4, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J. Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, Unpublished work. 2015.

- Torres, J.; Wang, J.; Parthasarathy, K.; Liu, D.X. The transmembrane oligomers of coronavirus protein E. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Parthasarathy, K.; Lin, X.; Saravanan, R.; Kukol, A.; Liu, D.X. Model of a putative pore: The pentameric α-helical bundle of SARS coronavirus E protein in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathy, K.; Ng, L.; Lin, X.; Liu, D.X.; Pervushin, K.; Gong, X.; Torres, J. Structural flexibility of the pentameric SARS coronavirus envelope protein ion channel. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, L39–L41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathy, K.; Lu, H.; Surya, W.; Vararattanavech, A.; Pervushin, K.; Torres, A. Expression and purification of coronavirus envelope proteins using a modified beta-barrel construct. Prot. Exp. Purif. 2012, 85, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

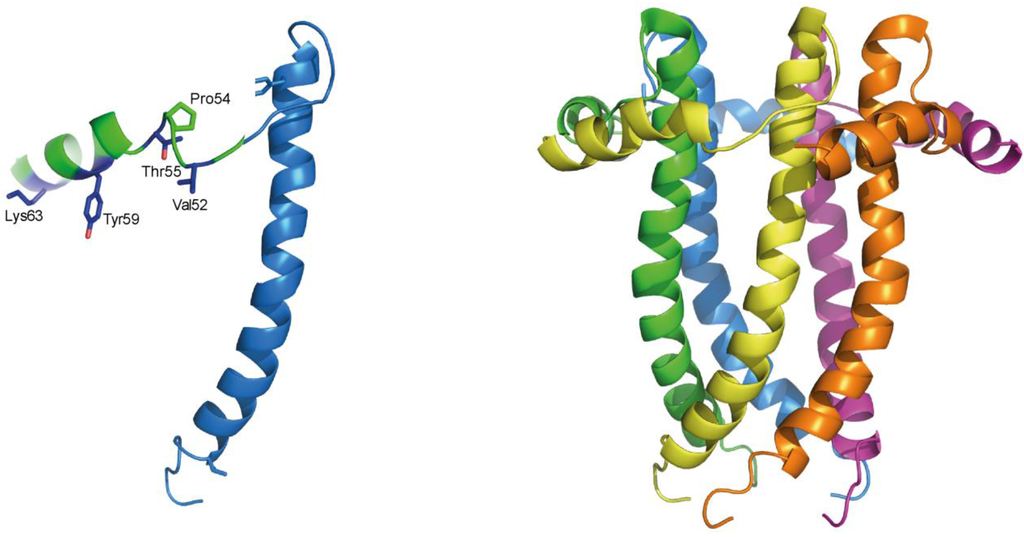

- Li, Y.; Surya, W.; Claudine, S.; Torres, J. Structure of a Conserved Golgi Complex-targeting Signal in Coronavirus Envelope Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 12535–12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervushin, K.; Tan, E.; Parthasarathy, K.; Lin, X.; Jiang, F.L.; Yu, D.; Vararattanavech, A.; Soong, T.W.; Liu, D.X.; Torres, J. Structure and inhibition of the SARS coronavirus envelope protein ion channel. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surya, W.; Li, Y.; Verdià-Bàguena, C.; Aguilella, V.M.; Torres, J. MERS coronavirus envelope protein has a single transmembrane domain that forms pentameric ion channels. Virus Res. 2015, 201, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdia-Baguena, C.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Alcaraz, A.; DeDiego, M.L.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus E protein forms ion channels with functionally and structurally-involved membrane lipids. Virology 2012, 432, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, L.; Gage, P.; Ewart, G. Hexamethylene amiloride blocks E protein ion channels and inhibits coronavirus replication. Virology 2006, 353, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, J.; Repass, J.F.; Maeda, A.; Makino, S. Membrane topology of coronavirus E protein. Virology 2001, 281, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Liao, Y.; Torres, J.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Biochemical evidence for the presence of mixed membrane topologies of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus envelope protein expressed in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3192–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Maheswari, U.; Parthasarathy, K.; Ng, L.F.; Liu, D.X.; Gong, X.D. Conductance and amantadine binding of a pore formed by a lysine-flanked transmembrane domain of SARS coronavirus envelope protein. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.W.; Vararattanavech, A.; Nordin, N.; Eshaghi, S.; Torres, J. A cost-effective method for simultaneous homo-oligomeric size determination and monodispersity conditions for membrane proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 416, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramjeesingh, M.; Huan, L.J.; Garami, E.; Bear, C.E. Novel method for evaluation of the oligomeric structure of membrane proteins. Biochem. J. 1999, 342 Pt 1, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surya, W.; Samsó, M.; Torres, J. Structural and Functional Aspects of Viroporins in Human Respiratory Viruses: Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Coronaviruses. In Respiratory Disease and Infection-A New Insight; Vats, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Pithadia, A.S.; Bhat, J.; Bera, S.; Midya, A.; Fierke, C.A.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Bhunia, A. Self-Assembly of a Nine-Residue Amyloid-Forming Peptide Fragment of SARS Corona Virus E-Protein: Mechanism of Self Aggregation and Amyloid-Inhibition of hIAPP. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2249–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.R.; Lin, L.D.; Machamer, C.E. Identification of a Golgi complex-targeting signal in the cytoplasmic tail of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 5794–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, L.D.; White, J.M. Mutational analysis of the candidate internal fusion peptide of the avian leukosis and sarcoma virus subgroup A envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3259–3267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Watanabe, S.; Sanchez, A.; Whitt, M.A.; Kawaoka, Y. Mutational analysis of the putative fusion domain of Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 8907–8912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolfsberg, T.G.; Straight, P.D.; Gerena, R.L.; Huovila, A.P.; Primakoff, P.; Myles, D.G.; White, J.M. ADAM, a widely distributed and developmentally regulated gene family encoding membrane proteins with a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain. Dev. Biol. 1995, 169, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, A.C.; Gichuhi, P.M.; Jones, R.; Hall, L. Cloning and analysis of monkey fertilin reveals novel alpha subunit isoforms. Biochem. J. 1995, 307, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitt, M.A.; Zagouras, P.; Crise, B.; Rose, J.K. A fusion-defective mutant of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 4907–4913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kielian, M.; Rey, F.A. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: More than one way to make a hairpin. Nat. Rev. 2006, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, F.A.; Heinz, F.X.; Mandl, C.; Kunz, C.; Harrison, S.C. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature 1995, 375, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, M.J.; Steger, H.K. HIV-1 gp41 as a target for viral entry inhibition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 1805–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langosch, D.; Hofmann, M.; Ungermann, C. The role of transmembrane domains in membrane fusion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, R.T.; Kushnir, A.S.; White, J.M. The transmembrane domain of influenza hemagglutinin exhibits a stringent length requirement to support the hemifusion to fusion transition. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odell, D.; Wanas, E.; Yan, J.; Ghosh, H.P. Influence of membrane anchoring and cytoplasmic domains on the fusogenic activity of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 7996–8000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giraudo, C.G.; Hu, C.; You, D.; Slovic, A.M.; Mosharov, E.V.; Sulzer, D.; Melia, T.J.; Rothman, J.E. SNAREs can promote complete fusion and hemifusion as alternative outcomes. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, M.W.; Peplowska, K.; Rohde, J.; Poschner, B.C.; Ungermann, C.; Langosch, D. Self-interaction of a SNARE transmembrane domain promotes the hemifusion-to-fusion transition. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 364, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.; Peplowska, K.; Rohde, J.; Ungermann, C.; Langosch, D. Role of the Vam3p transmembrane segment in homodimerization and SNARE complex formation. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 7654–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langosch, D.; Crane, J.M.; Brosig, B.; Hellwig, A.; Tamm, L.K.; Reed, J. Peptide mimics of SNARE transmembrane segments drive membrane fusion depending on their conformational plasticity. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 311, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, S.M.; Greenfield, N.; Lenard, J.; Lentz, B.R. VSV transmembrane domain (TMD) peptide promotes PEG-mediated fusion of liposomes in a conformationally sensitive fashion. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 14925–14934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleverley, D.Z.; Lenard, J. The transmembrane domain in viral fusion: Essential role for a conserved glycine residue in vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3425–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellgren, B.W.; Creamer, T.P. Side-chain entropy effects on protein secondary structure formation. Proteins 2006, 62, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, F.; Stegen, C.F.; Masters, P.S.; Samsonoff, W.A. Analysis of constructed E gene mutants of mouse hepatitis virus confirms a pivotal role for E protein in coronavirus assembly. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7885–7894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corse, E.; Machamer, C.E. The cytoplasmic tail of infectious bronchitis virus E protein directs Golgi targeting. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamirande, E.W.; Dediego, M.L.; Roberts, A.; Jackson, J.P.; Alvarez, E.; Sheahan, T.; Shieh, W.J.; Zaki, S.R.; Baric, R.; Enjuanes, L.; et al. A live attenuated SARS coronavirus is immunogenic and efficacious in golden Syrian hamsters. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 7721–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, Y.L.; Teoh, K.T.; Lo, J.; Chan, C.M.; Kien, F.; Escriou, N.; Tsao, S.W.; Nicholls, J.M.; Altmeyer, R.; Peiris, J.S.; et al. The M, E, and N structural proteins of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus are required for efficient assembly, trafficking, and release of virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11318–11330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennema, H.; Godeke, G.J.; Rossen, J.W.; Voorhout, W.F.; Horzinek, M.C.; Opstelten, D.J.; Rottier, P.J. Nucleocapsid-independent assembly of coronavirus-like particles by co-expression of viral envelope protein genes. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.; Lin, P.H.; Liu, C.Y.Y.; Lee, S.P.; Chao, Y.C. Assembly of human severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like particles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.P.; Liu, D.X. The missing link in coronavirus assembly. Retention of the avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus envelope protein in the pre-Golgi compartments and physical interaction between the envelope and membrane proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 17515–17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogue, B.G.; Machamer, C.E. Coronavirus structural proteins and virus assembly. In Nidoviruses; Perlman, S., Gallagher, T., Snijder, E.J., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, C.A.; Vennema, H.; Rottier, P.J. Assembly of the coronavirus envelope: Homotypic interactions between the M proteins. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4967–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottier, P.J.M. The Coronaviridae; Siddell, S.G., Ed.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Baudoux, P.; Carrat, C.; Besnardeau, L.; Charley, B.; Laude, H. Coronavirus pseudoparticles formed with recombinant M and E proteins induce alpha interferon synthesis by leukocytes. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8636–8643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuo, L.; Masters, P.S. Evolved variants of the membrane protein can partially replace the envelope protein in murine coronavirus assembly. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12872–12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, K.T.; Siu, Y.L.; Chan, W.L.; Schluter, M.A.; Liu, C.J.; Peiris, J.S.; Bruzzone, R.; Margolis, B.; Nal, B. The SARS coronavirus E protein interacts with PALS1 and alters tight junction formation and epithelial morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 3838–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Enjuanes, L.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castano-Rodriguez, C. The PDZ-Binding Motif of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Is a Determinant of Viral Pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, F.; Zhang, M.J. Structures and target recognition modes of PDZ domains: Recurring themes and emerging pictures. Biochem. J. 2013, 455, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.K.; Pan, L.F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.J. Extensions of PDZ domains as important structural and functional elements. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penkert, R.R.; DiVittorio, H.M.; Prehoda, K.E. Internal recognition through PDZ domain plasticity in the Par-6-Pals1 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, B.J.; Christopherson, K.S.; Prehoda, K.E.; Bredt, D.S.; Lim, W.A. Unexpected modes of PDZ domain scaffolding revealed by structure of nNOS-syntrophin complex. Science 1999, 284, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiVittorio, H.; Penkert, R.; Prehoda, K.E. Mechanism of PDZ internal peptide recognition: Bypassing the requirement for a C-terminus. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 138–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Boehm, J.; Lee, J.C. p38 map kinases: Key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, S.L.; de Lang, A.; van den Brand, J.M.A.; Leijten, L.M.; van IJcken, W.F.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; van Amerongen, G.; Kuiken, T.; Andeweg, A.C.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; et al. Exacerbated Innate Host Response to SARS-CoV in Aged Non-Human Primates. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javier, R.T.; Rice, A.P. Emerging Theme: Cellular PDZ Proteins as Common Targets of Pathogenic Viruses. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11544–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.L.; Song, W.; Gao, Z.; Su, X.F.; Nie, H.G.; Jiang, Y.; Peng, J.B.; He, Y.X.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; et al. SARS-CoV proteins decrease levels and activity of human ENaC via activation of distinct PKC isoforms. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 296, L372–L383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetherill, L.F.; Holmes, K.K.; Verow, M.; Muller, M.; Howell, G.; Harris, M.; Fishwick, C.; Stonehouse, N.; Foster, R.; Blair, G.E.; et al. High-Risk Human Papillomavirus E5 Oncoprotein Displays Channel-Forming Activity Sensitive to Small-Molecule Inhibitors. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 5341–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.J.; Finbow, M.E.; Andresson, T.; Mclean, P.; Smith, K.; Bubb, V.; Schlegel, R. Bovine Papillomavirus-E5 Oncoprotein Binds to the 16k Component of Vacuolar H+-Atpases. Nature 1991, 352, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapiro, F.; Sparkowski, J.; Adduci, A.; Suprynowicz, F.; Schlegel, R.; Grinstein, S. Golgi alkalinization by the papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 148, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blount, R.E., Jr.; Morris, J.A.; Savage, R.E. Recovery of cytopathogenic agent from chimpanzees with coryza. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1956, 92, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dowell, S.F.; Anderson, L.J.; Gary, H.E., Jr.; Erdman, D.D.; Plouffe, J.F.; File, T.M., Jr.; Marston, B.J.; Breiman, R.F. Respiratory syncytial virus is an important cause of community-acquired lower respiratory infection among hospitalized adults. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 174, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Thompson, W.W.; Viboud, C.G.; Ringholz, C.M.; Cheng, P.Y.; Steiner, C.; Abedi, G.R.; Anderson, L.J.; Brammer, L.; Shay, D.K. Hospitalizations Associated With Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the United States, 1993–2008. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, H.; Nokes, D.J.; Gessner, B.D.; Dherani, M.; Madhi, S.A.; Singleton, R.J.; O’Brien, K.L.; Roca, A.; Wright, P.F.; Bruce, N.; et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Singh, M.; Malashkevich, V.N.; Kim, P.S. Structural characterization of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein core 2. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14172–14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, D.M.; Barney, S.; Lambert, A.L.; Guthrie, K.; Medinas, R.; Davis, D.E.; Bucy, T.; Erickson, J.; Merutka, G.; Petteway, S.R. Peptides from conserved regions of paramyxovirus fusion (F) proteins are potent inhibitors of viral fusion. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 2186–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, N.E.; Hoang, H.N.; Desai, V.S.; Letouze, E.; Young, P.R.; Fairlie, D.P. Modular alpha-helical mimetics with antiviral activity against respiratory syncitial virus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13284–13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastey, M.K.; Gower, T.L.; Spearman, P.W.; Crowe, J.E.; Graham, B.S. A RhoA-derived peptide inhibits syncytium formation induced by respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus type 3. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Razinkov, V.; Gazumyan, A.; Nikitenko, A.; Ellestad, G.; Krishnamurthy, G. RFI-641 inhibits entry of respiratory syncytial virus via interactions with fusion protein. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.L.; Panis, M.L.; Ho, E.; Lin, K.Y.; Krawczyk, S.H.; Grant, D.M.; Cai, R.; Swaminathan, S.; Chen, X.; Cihlar, T. Small molecules VP-14637 and JNJ-2408068 inhibit respiratory syncytial virus fusion by similar mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2460–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roymans, D.; de Bondt, H.L.; Arnoult, E.; Geluykens, P.; Gevers, T.; van Ginderen, M.; Verheyen, N.; Kim, H.D.; Willebrords, R.; Bonfanti, J.F.; et al. Binding of a potent small-molecule inhibitor of six-helix bundle formation requires interactions with both heptad-repeats of the RSV fusion protein. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Behera, A.K.; Lockey, R.F.; Zhang, J.; Bhullar, G.; de La Cruz, C.P.; Chen, L.C.; Leong, K.W.; Huang, S.K.; Mohapatra, S.S. Intranasal gene transfer by chitosan-DNA nanospheres protects BALB/c mice against acute respiratory syncytial virus infection. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002, 13, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Kong, X.; Mohapatra, S.; san Juan-Vergara, H.; Hellermann, G.; Behera, S.; Singam, R.; Lockey, R.F.; Mohapatra, S.S. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection with intranasal siRNA nanoparticles targeting the viral NS1 gene. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 233–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, J.S.; Chen, M.; Joyce, M.G.; Sastry, M.; Stewart-Jones, G.B.E.; Yang, Y.P.; Zhang, B.S.; Chen, L.; Srivatsan, S.; Zheng, A.Q.; et al. Structure-Based Design of a Fusion Glycoprotein Vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Science 2013, 342, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLellan, J.S.; Chen, M.; Leung, S.; Graepel, K.W.; Du, X.L.; Yang, Y.P.; Zhou, T.Q.; Baxa, U.; Yasuda, E.; Beaumont, T.; et al. Structure of RSV Fusion Glycoprotein Trimer Bound to a Prefusion-Specific Neutralizing Antibody. Science 2013, 340, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepens, B.; Sedeyn, K.; Vande Ginste, L.; de Baets, S.; Schotsaert, M.; Roose, K.; Houspie, L.; van Ranst, M.; Gilbert, V.; van Rooijen, N.; et al. Protection and mechanism of action of a novel human respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate based on the extracellular domain of small hydrophobic protein. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1436–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, G.H.; Boyapalle, S.; Wong, T.; Opoku-Nsiah, K.; Bedi, R.; Crannell, W.C.; Perry, A.F.; Nguyen, H.; Sampayo, V.; Devareddy, A.; et al. Mucosal delivery of a double-stapled RSV peptide prevents nasopulmonary infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory syncytial virus activity: United States, 1999–2000 season. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2000, 49, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, L.B.; Polak, M.J.; Masaquel, A.; Mahadevia, P.J. Cost-Effectiveness of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prophylaxis with Palivizumab among Preterm Infants Covered by Medicaid in the United States. Value Health 2011, 14, A118–A118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.B.; Powell, K.R.; Macdonald, N.E.; Gala, C.L.; Menegus, M.E.; Suffin, S.C.; Cohen, H.J. Respiratory Syncytial Viral-Infection in Children with Compromised Immune Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Melero, J.A. Progress in understanding and controlling respiratory syncytial virus: Still crazy after all these years. Virus Res. 2011, 162, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krusat, T.; Streckert, H.J. Heparin-dependent attachment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) to host cells. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, R.A. Paramyxovirus fusion: A hypothesis for changes. Virology 1993, 197, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Mottet, G. Membrane orientation and oligomerization of the small hydrophobic protein of human respiratory syncytial virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1993, 74, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.W.; Tan, E.; Lin, X.; Yu, D.; Wang, J.; Tan, G.M.-Y.; Vararattanavech, A.; Yeo, C.Y.; Soon, C.H.; Soong, T.W.; et al. The small hydrophobic protein of the human respiratory syncytial virus forms pentameric ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 24671–24689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.E.; Morrow, S.; Scott, M.; Young, B.; Toms, G.L. Comparative Virulence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Subgroup-A and Subgroup-B. Lancet 1989, 1, 777–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcconnochie, K.M.; Hall, C.B.; Walsh, E.E.; Roghmann, K.J. Variation in Severity of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Infections with Subtype. J. Pediatr. 1990, 117, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.B.; Walsh, E.E.; Schnabel, K.C.; Long, C.E.; Mcconnochie, K.M.; Hildreth, S.W.; Anderson, L.J. Occurrence of Group-A and Group-B of Respiratory Syncytial Virus over 15 Years-Associated Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics in Hospitalized and Ambulatory Children. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 162, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rixon, H.W.; Brown, G.; Aitken, J.; McDonald, T.; Graham, S.; Sugrue, R.J. The small hydrophobic (SH) protein accumulates within lipid-raft structures of the Golgi complex during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Techaarpornkul, S.; Barretto, N.; Peeples, M.E. Functional analysis of recombinant respiratory syncytial virus deletion mutants lacking the small hydrophobic and/or attachment glycoprotein gene. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6825–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukreyev, A.; Whitehead, S.S.; Murphy, B.R.; Collins, P.L. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus from which the entire SH gene has been deleted grows efficiently in cell culture and exhibits site-specific attenuation in the respiratory tract of the mouse. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8973–8982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karron, R.A.; Buonagurio, D.A.; Georgiu, A.F.; Whitehead, S.S.; Adamus, J.E.; Harris, D.O.; Clements-Mann, M.L.; Randolph, V.B.; Udem, S.A.; Murphy, B.R.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) SH and G proteins are not essential for viral replication in vitro: Clinical evaluation and molecular characterization of a cold-passaged, attenuated RSV subgroup B mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13961–13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, S.S.; Bukreyev, A.; Teng, M.N.; Firestone, C.Y.; St Claire, M.; Elkins, W.R.; Collins, P.L.; Murphy, B.R. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus bearing a deletion of either the NS2 or SH gene is attenuated in chimpanzees. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 3438–3442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, X.; Tang, R.; Munoz, M.; Nguyen, N. Recombinant respiratory syncytial viruses with deletions in the NS1, NS2, SH, and M2–2 genes are attenuated in vitro and in vivo. Virology 2000, 273, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.; Wyld, S.; Valarcher, J.F.; Guzman, E.; Thom, M.; Widdison, S.; Buchholz, U.J. Recombinant bovine respiratory syncytial virus with deletion of the SH gene induces increased apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro, and is attenuated and induces protective immunity in calves. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, S.; Tran, K.C.; Luthra, P.; Teng, M.N.; He, B. Function of the respiratory syncytial virus small hydrophobic protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8361–8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Patel, J.; Fuentes, S.; Lin, Y.A.; Anderson, D.; Sakamoto, K.; Wang, L.F.; He, B.A. Function of the Small Hydrophobic Protein of J Paramyxovirus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, P.J.M.; Boyle, D.B.; Eaton, B.T.; Wang, L.F. The complete genome sequence of J virus reveals a unique genome structure in the family Paramyxoviridae. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 10690–10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Bright, A.C.; Rothermel, T.A.; He, B. Induction of apoptosis by paramyxovirus simian virus 5 lacking a small hydrophobic gene. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 3371–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.L.; Fuentes, S.M.; Wang, P.; Taddeo, E.C.; Klatt, A.; Henderson, A.J.; He, B. Function of small hydrophobic proteins of paramyxovirus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichinohe, T.; Pang, I.K.; Iwasaki, A. Influenza virus activates inflammasomes via its intracellular M2 ion channel. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Yanagi, Y.; Ichinohe, T. Encephalomyocarditis virus viroporin 2B activates NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segovia, J.; Sabbah, A.; Mgbemena, V.; Tsai, S.Y.; Chang, T.H.; Berton, M.T.; Morris, I.R.; Allen, I.C.; Ting, J.P.Y.; Bose, S. TLR2/MyD88/NF-kappa B Pathway, Reactive Oxygen Species, Potassium Efflux Activates NLRP3/ASC Inflammasome during Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafilou, K.; Kar, S.; Vakakis, E.; Kotecha, S.; Triantafilou, M. Human respiratory syncytial virus viroporin SH: A viral recognition pathway used by the host to signal inflammasome activation. Immunology 2013, 140, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.W.; Ng, L.; Xin, L.; Gong, X.; Torres, J. Structure and ion channel activity of the human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) small hydrophobic protein transmembrane domain. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.W.; Torres, J. Structural and functional aspects of the small hydrophobic (SH) protein in the human respiratory syncytial virus. In Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection; Resch, B., Ed.; Intech: Janeza Trdine, Croatia, 2011; pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; To, J.; Verdià-Baguena, C.; Dossena, S.; Surya, W.; Huang, M.; Paulmichl, M.; Liu, D.X.; Aguilella, V.M.; Torres, J. Inhibition of the Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Small Hydrophobic Protein and Structural variations in a bicelle environment. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11899–11914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, J.R.; Chou, J.J. Structure and mechanism of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Nature 2008, 451, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, B.; Xie, S.; Berardi, M.J.; Zhao, X.; Dev, J.; Yu, W.; Sun, B.; Chou, J.J. Unusual architecture of the p7 channel from hepatitis C virus. Nature 2013, 498, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, L.I.; Shaw, C.A.; Aideyan, L.O.; Jewell, A.M.; Dawson, B.C.; Haq, T.R.; Piedra, P.A. Gene Sequence Variability of the Three Surface Proteins of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (HRSV) in Texas. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.D.; Vazquez, M.; Buonocore, L.; Kahn, J.S. Conservation of the respiratory syncytial virus SH gene. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Olmsted, R.A.; Johnson, P.R. The small hydrophobic protein of human respiratory syncytial virus: Comparison between antigenic subgroups A and B. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, K.; Tanabayashi, K.; Hishiyama, M.; Yamada, A. The mumps virus SH protein is a membrane protein and not essential for virus growth. Virology 1996, 225, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elango, N.; Kovamees, J.; Varsanyi, T.M.; Norrby, E. Messenger-RNA Sequence and Deduced Amino-Acid Sequence of the Mumps-Virus Small Hydrophobic Protein Gene. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Low, K.W.; Tan, T.; Ng, K.; Tan, B.H.; Sugrue, R.J. The RSV F and G glycoproteins interact to form a complex on the surface of infected cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 366, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rixon, H.W.; Brown, G.; Murray, J.T.; Sugrue, R.J. The respiratory syncytial virus small hydrophobic protein is phosphorylated via a mitogen-activated protein kinase p38-dependent tyrosine kinase activity during virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlender, J.; Zimmer, G.; Herrler, G.; Conzelmann, K.K. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion protein subunit F2, not attachment protein G, determines the specificity of RSV infection. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 4609–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karger, A.; Schmidt, U.; Buchholz, U.J. Recombinant bovine respiratory syncytial virus with deletions of the G or SH genes: G and F proteins bind heparin. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jain, N.; Limpanawat, S.; To, J.; Quistgaard, E.M.; Nordlund, P.; Thanabalu, T.; Torres, J. Interaction between human BAP31 and Respiratory Syncytial Virus Small Hydrophobic (SH) protein. Virology 2015, 482, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Heath-Engel, H.; Zhang, D.; Nguyen, N.; Thomas, D.Y.; Hanrahan, J.W.; Shore, G.C. BAP31 Interacts with Sec61 Translocons and Promotes Retrotranslocation of CFTRΔF508 via the Derlin-1 Complex. Cell 2008, 133, 1080–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, T.; Schamel, W.W.; Kim, K.M.; Watanabe, T.; Becker, B.; Nielsen, P.J.; Reth, M. The specificity of association of the IgD molecule with the accessory proteins BAP31/BAP29 lies in the IgD transmembrane sequence. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quistgaard, E.M.; Low, C.; Moberg, P.; Guettou, F.; Maddi, K.; Nordlund, P. Structural and biophysical characterization of the cytoplasmic domains of human BAP29 and BAP31. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, F.W.H.; Nguyen, M.; Kwan, T.; Branton, P.E.; Nicholson, D.W.; Cromlish, J.A.; Shore, G.C. p28 Bap31, a Bcl-2/Bcl-X-L- and procaspase-8-associated protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 139, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckenridge, D.G.; Nguyen, M.; Kuppig, S.; Reth, M.; Shore, G.C. The procaspase-8 isoform, procaspase-8L, recruited to the BAP31 complex at the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4331–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckenridge, D.G.; Stojanovic, M.; Marcellus, R.C.; Shore, G.C. Caspase cleavage product of BAP31 induces mitochondrial fission through endoplasmic reticulum calcium signals, enhancing cytochrome c release to the cytosol. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, E.; Sabatini, R.; Rampino, G.; De Falco, F.; Di Ianni, M.; Falzetti, F.; Fettucciari, K.; Bartoli, A.; Screpanti, I.; Marconi, P. Novel targets for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in B-CLL. Blood 2010, 116, 2713–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasawa, R.; Mahul-Mellier, A.L.; Datler, C.; Pazarentzos, E.; Grimm, S. Fis1 and Bap31 bridge the mitochondria-ER interface to establish a platform for apoptosis induction. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, K.; Mossadegh, N.; Kohl, A.; Komposch, G.; Schenkel, J.; Alonso, A.; Tomakidi, P. The HPV-16 E5 protein inhibits TRAIL- and FasL-mediated apoptosis in human keratinocyte raft cultures. Intervirology 2004, 47, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, J.A.; Laimins, L.A. Bap31 is a novel target of the human papillomavirus E5 protein. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10042–10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walensky, L.D.; Bird, G.H. Hydrocarbon-Stapled Peptides: Principles, Practice, and Progress. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6275–6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellmann-Sickert, K.; Stone, T.A.; Poulsen, B.E.; Deber, C.M. Efflux by Small Multidrug Resistance Proteins is Inhibited by Membrane-Interactive Helix-Stapled Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 290, 1752–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).