Human Prion Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Public Health

Abstract

1. Introduction and Epidemiology

2. Classification of Prion Diseases (Table 1)

2.1. Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (sCJD)

- MM1/MV1: classical, rapid dementia, myoclonus.

- VV2/MV2: early cerebellar signs, slower progression.

- MM2C: predominantly cognitive, “Alzheimer-like” onset.

- MM2T/FFI: insomnia and autonomic failure.

- VV1: slow course, psychiatric or atypical onset.

| Prion Disease Type | Main Clinical Symptoms | Age of Onset | Disease Duration | Clinical Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sCJD | Rapid cognitive decline, myoclonus, ataxia | 50–75 years | 4–6 months | Rapid, progressive decline; myoclonus, visual disturbances |

| vCJD | Psychiatric symptoms (depression, hallucinations), sensory disturbances, ataxia | 20–30 years | 13–14 months | Slowly progressive, with early psychiatric symptoms |

| iCJD | Rapidly progressive cognitive decline, Cerebellar Signs, Myoclonus, Visual symptoms, psychiatric symptoms | 30–60 years | 5–18 months | Rapid cognitive decline, visual symptoms, myoclonus |

| gCJD | Ataxia, cognitive decline, dementia | 30–60 years | Years | Long course, with early onset and genetic mutations (e.g., E200K, P102L) |

| FFI | Insomnia, autonomic dysfunction, cognitive decline | 30–60 years | 1–2 years | Sleep disturbances, progressive autonomic failure, thalamic damage |

| GSS | Ataxia, dementia, amyloid plaques | 30–60 years | 5–10 years | Slowly progressive, cerebellar ataxia, long disease course |

| Molecular Subtype | Codon 129 Genotype | PrPSc Type | Typical Clinical Phenotype | Key Neuropathology | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM1 | Met/Met | 1 | Rapid dementia, early myoclonus, classic PSWC on EEG | Fine spongiosis, cortical + basal ganglia involvement | Most common subtype |

| MM2-cortical (MM2C) | Met/Met | 2 | Slowly progressive dementia, cortical symptoms | Prominent cortical spongiosis | Often MRI cortical ribboning |

| MM2-thalamic (MM2T/sporadic FFI-like) | Met/Met | 2 | Sleep disturbances, dysautonomia | Thalamic neurodegeneration | Phenotype resembles FFI |

| MV1 | Met/Val | 1 | Classic sCJD phenotype | Mixed spongiosis | Intermediate frequency |

| MV2 (MV2K, MV2C) | Met/Val | 2 | Ataxia, cerebellar signs, longer course | Kuru plaques (MV2K) or cortical spongiosis (MV2C) | Frequently misdiagnosed initially |

| VV1 | Val/Val | 1 | Early psychiatric prodrome, slower progression | Cortical involvement | Very rare subtype |

| VV2 | Val/Val | 2 | Cerebellar variant: prominent ataxia | Spongiform change in cerebellum and basal ganglia | ~15% of sCJD cases |

2.2. Genetic Prion Diseases

- E200K and V210I: “classical” genetic CJD (gCJD), clinically similar to sporadic forms with rapidly progressive dementia and myoclonus [39].

- V180I: slower progression, often mimicking Alzheimer’s disease due to predominant cortical symptoms [30].

- P102L, A117V, and related mutations: Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome (GSS), typically with early cerebellar ataxia and long disease course [36].

2.3. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (iCJD)

2.4. Variant CJD (vCJD)

2.5. Kuru (Historical)

3. Pathogenesis

4. Main Histopathological Findings

5. Clinical Pictures

Major Diagnostic Clinical Patterns

6. Diagnostic Workup

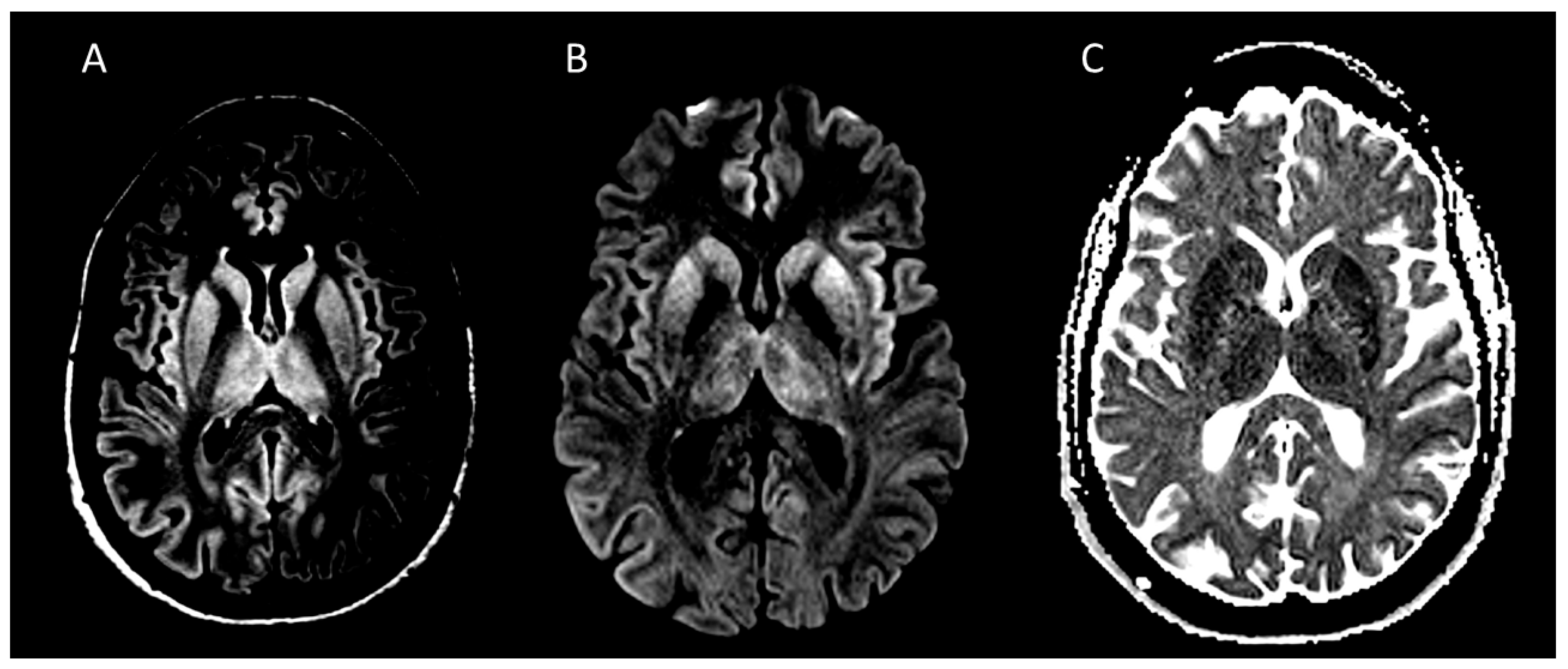

6.1. Neuroimaging

6.2. PET/SPECT

6.3. EEG

6.4. CSF Biomarkers

6.5. Genetic Testing

7. Diagnostic Criteria for Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease

7.1. Diagnostic Criteria for Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (sCJD)

7.1.1. Definite sCJD

- Progressive neuropsychiatric syndrome with neuropathological, immunocytochemical, or biochemical confirmation of pathological prion protein.

7.1.2. Probable sCJD

- Rapidly progressive cognitive impairment plus at least two of the following clinical features: myoclonus, visual or cerebellar disturbance, pyramidal or extrapyramidal signs, akinetic mutism, and a typical EEG showing periodic sharp-wave complexes (PSWC); or

- Rapidly progressive cognitive impairment plus at least two of the above clinical features and a typical MRI pattern; or

- Rapidly progressive cognitive impairment plus at least two of the above clinical features and a positive CSF 14-3-3 protein; or

- Progressive neuropsychiatric syndrome with a positive RT-QuIC assay in CSF or other tissues;

- Exclusion of alternative diagnoses.

7.1.3. Possible sCJD

- Rapidly progressive cognitive impairment plus at least two of the following clinical features: myoclonus, visual or cerebellar disturbance, pyramidal or extrapyramidal signs, akinetic mutism, with disease duration <2 years.

7.2. Diagnostic Criteria for Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (iCJD)

7.2.1. Definite iCJD

- Mandatory neuropathological confirmation (autopsy or brain biopsy demonstrating pathological prion protein).

7.2.2. Probable iCJD

- A rapidly progressive neurological syndrome compatible with CJD (e.g., dementia, ataxia, myoclonus, pyramidal or extrapyramidal signs);

- Supportive CSF and instrumental findings (positive 14-3-3 protein or RT-QuIC, MRI hyperintensity in the caudate nucleus, putamen, or cerebral cortex, EEG showing PSWC);

- A documented history of iatrogenic exposure (e.g., cadaveric human growth hormone therapy, dura mater grafts, contaminated neurosurgical instruments, corneal transplantation, or blood transfusion from an infected donor).

7.3. Diagnostic Criteria for Familial Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (fCJD)

7.3.1. Definite fCJD

- Neuropathological confirmation (spongiform change, neuronal loss, gliosis, and pathological prion protein deposition), or

- Genetic confirmation of a known pathogenic PRNP mutation associated with CJD [92].

7.3.2. Probable fCJD

- A clinical syndrome compatible with CJD;

- A family history of CJD or another prion disease;

- Supportive CSF biomarkers (14-3-3 protein, tau, or RT-QuIC) and/or characteristic MRI findings (hyperintensity in the caudate nucleus, putamen, or cerebral cortex), in the absence of genetic or neuropathological confirmation.

7.3.3. Possible fCJD

- A compatible clinical syndrome and positive family history, without typical biomarker or neuroimaging findings.

8. Differential Diagnosis (Table 4)

| Disease Group | Onset E Progression | Key Clinical Features | MRI Features | Csf Findings | Response to Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prion diseases | Subacute onset with multidimensional cognitive impairment (weeks/months) | Rapidly progressive dementia, myoclonus, cerebellar signs, akinetic mutism | Cortical ribboning and/or basal ganglia hyperintensity on DWI/FLAIR, restricted diffusion | Usually normal cell count; Increase intotal tau; 14-3-3 (non-specific); RT-QuIC positive | Steady progression, lack of response to treatment |

| Autoimmune encephalitis | Subacute onset (days/weeks) | Subacute neuropsychiatric symptoms, seizures, cognitive decline, and movement abnormalities, | Limbic or multifocal T2/FLAIR hyperintensities, often non-DWI-restricted | Mild pleocytosis, oligoclonal bands, neuronal antibodies | Response to immunotherapy |

| Infectious encephalitis | Acute or subacute onset (days/weeks) | Fever, altered consciousness, seizures, systemic infection signs | Temporal lobe involvement (HSV), focal or diffuse inflammatory lesions | Pleocytosis, Increase in protein, pathogen-specific PCR positive | Response to antimicrobials |

| Toxic–metabolic encephalopathy | Subacute onset (weeks) | Rapidly progressive cognitive decline, ataxia, and ocular or behavioral symptoms | Diffuse cortical or basal ganglia changes, often reversible | Usually normal or mildly abnormal | Identifiable metabolic/toxic trigger, reversibility with correction |

| Seizure-related conditions (NCSE) | Acute onset (hours/days) | Fluctuating cognition, myoclonus, subtle motor phenomena | Cortical signal changes are possible, often transient | Typically normal | Rapid improvement after antiseizure treatment |

| Vascular and inflammatory vasculopathies | Acute or stepwise deficits (weeks) | Headache, blood pressure fluctuations | Vascular distribution, vasogenic edema, reversibility (PRES/RCVS) | The variable may show inflammation | Response to steroids or immunotherapy |

| Neoplastic/paraneoplastic disorders | Subacute (weeks/months) | Neuropsychiatric decline, known malignancy | Mass lesions, leptomeningeal enhancement, atypical diffusion | Elevated protein, malignant cells or antibodies | Treatable etiology, oncologic context, inflammatory or malignant CSF |

| Rapidly progressive neurodegenerative dementias | Subacute onset with rapidly progressive dementia (weeks/months) | Cognitive decline with atypical rapidity | Atrophy or non-specific changes | Neurodegenerative biomarkers; RT-QuIC negative | Slower evolution, lack of response to treatment |

8.1. Immune-Mediated Encephalopathies

8.2. Infectious Encephalitis

8.3. Toxic–Metabolic and Seizure-Related Conditions

8.4. Vascular and Inflammatory Vasculopathies

8.5. Neoplastic and Paraneoplastic Disorders

8.6. Rapidly Progressive Neurodegenerative Dementias

9. Infection-Control and Procedural Precautions When Prion Is in the Differential Diagnosis

10. Therapeutic Strategies

11. An Emblematic Clinical Case

12. Lessons Learned from This Clinical Case

13. Public Health Implications and Preventive Strategies

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PrP | Prion protein |

| PrPC | Cellular prion protein (normal form) |

| PrPSc | Scrapie-associated pathological prion protein |

| TSE | Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy |

| CJD | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| sCJD | Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| gCJD/fCJD | Genetic/familial Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| vCJD | Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| iCJD | Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| FFI | Fatal Familial Insomnia |

| GSS | Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease |

| RPD | Rapidly progressive dementia |

| PRNP | Prion protein gene |

| 129M/V | Methionine/Valine polymorphism at codon 129 of PRNP |

| MM, MV, VV | Methionine/Methionine; Methionine/Valine; Valine/Valine genotypes |

| Type 1/Type 2 PrPSc | Electrophoretic prion protein types |

| E200K, D178N, P102L, V180I, etc. | Common PRNP pathogenic mutations |

| PSWCs | Periodic Sharp Wave Complexes (EEG hallmark) |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| FLAIR | Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| FDG-PET | Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| RT-QuIC | Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion |

| qRT-QuIC/2G-RT-QuIC | First or second generation RT-QuIC |

| t-tau | Total tau protein |

| p-tau | Phosphorylated tau |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| 14-3-3 | CSF 14-3-3 protein |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

References

- Prusiner, S.B. Novel Proteinaceous Infectious Particles Cause Scrapie. Science 1982, 216, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B. Molecular Biology of Prion Diseases. Science 1991, 252, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, J. Prion Diseases of Humans and Animals: Their Causes and Molecular Basis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 519–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13363–13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-P.; Tian, T.-T.; Xiao, K.; Chen, C.; Zhou, W.; Liang, D.-L.; Cao, R.-D.; Shi, Q.; Dong, X.-P. Updated Global Epidemiology Atlas of Human Prion Diseases. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1411489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttley, L.; Carroll, C.; Wong, R.; Hilton, D.A.; Stevenson, M. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: A Systematic Review of Global Incidence, Prevalence, Infectivity, and Incubation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e2–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, P.; Appleby, B.; Brandel, J.-P.; Caughey, B.; Collins, S.; Geschwind, M.D.; Green, A.; Haïk, S.; Kovacs, G.G.; Ladogana, A.; et al. Biomarkers and Diagnostic Guidelines for Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Villar-Piqué, A.; Hermann, P.; Escaramís, G.; Calero, M.; Chen, C.; Kruse, N.; Cramm, M.; Golanska, E.; Sikorska, B.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Genetic Prion Diseases. Brain J. Neurol. 2022, 145, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerr, I.; Ladogana, A.; Mead, S.; Hermann, P.; Forloni, G.; Appleby, B.S. Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and Other Prion Diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2024, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minikel, E.V.; Vallabh, S.M.; Lek, M.; Estrada, K.; Samocha, K.E.; Sathirapongsasuti, J.F.; McLean, C.Y.; Tung, J.Y.; Yu, L.P.C.; Gambetti, P.; et al. Quantifying Prion Disease Penetrance Using Large Population Control Cohorts. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 322ra9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, A.M. Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kitamoto, T.; Mizusawa, H. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 153, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, C.L.; Harris, J.O.; Gajdusek, D.C.; Gibbs, C.J.; Bernoulli, C.; Asher, D.M. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Patterns of Worldwide Occurrence and the Significance of Familial and Sporadic Clustering. Ann. Neurol. 1979, 5, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cali, I.; Cohen, M.L.; Haïk, S.; Parchi, P.; Giaccone, G.; Collins, S.J.; Kofskey, D.; Wang, H.; McLean, C.A.; Brandel, J.-P.; et al. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease with Amyloid-β Pathology: An International Study. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Brandel, J.-P.; Sato, T.; Nakamura, Y.; MacKenzie, J.; Will, R.G.; Ladogana, A.; Pocchiari, M.; Leschek, E.W.; Schonberger, L.B. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Final Assessment. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD). Available online: https://www.bag.admin.ch/en/creutzfeldt-jakob-disease-cjd (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Appleby, B.S.; Shetty, S.; Elkasaby, M. Genetic Aspects of Human Prion Diseases. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1003056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.M.; Yu, M.; DeArmond, S.J.; Dillon, W.P.; Miller, B.L.; Geschwind, M.D. Human Growth Hormone–Related Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease with Abnormal Imaging. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Prion Diseases. Available online: https://www.Cdc.Gov/Prions/about/Index.Html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease (vCJD); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/vcjd/facts (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Istituto Superiore Di Sanità. Registers and Surveillance: National Registry of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and Related Disorders; Istituto Superiore Di Sanità: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind, M.D. Prion Diseases. Continuum 2015, 21, 1612–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñar-Morales, R.; Barrero-Hernández, F.; Aliaga-Martínez, L. Enfermedades por priones humanas. Una revisión general. Med. Clínica 2023, 160, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafe, R.; Arendt, C.T.; Hattingen, E. Human Prion Diseases and the Prion Protein—What Is the Current State of Knowledge? Transl. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 20220315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Alam, P.; Caughey, B. RT-QuIC and Related Assays for Detecting and Quantifying Prion-like Pathological Seeds of α-Synuclein. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, A.; Menart, A.C.; Hansen, B.E.; Ikram, M.A. Life Expectancy for Patients with Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2025, 82, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocchiari, M. Predictors of Survival in Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and Other Human Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. Brain 2004, 127, 2348–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, M.C.; Jurcau, A.; Diaconu, R.G.; Hogea, V.O.; Nunkoo, V.S. A Systematic Review of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Attempts. Neurol. Int. 2024, 16, 1039–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, I.; Parchi, P. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 153, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, T.; Sanjo, N. Systematic Review of Clinical and Pathophysiological Features of Genetic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Caused by a Val-to-Ile Mutation at Codon 180 in the Prion Protein Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerr, I.; Kallenberg, K.; Summers, D.M.; Romero, C.; Taratuto, A.; Heinemann, U.; Breithaupt, M.; Varges, D.; Meissner, B.; Ladogana, A.; et al. Updated Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Brain 2009, 132, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzi, A.; Pascuzzo, R.; Blevins, J.; Moscatelli, M.E.M.; Grisoli, M.; Lodi, R.; Doniselli, F.M.; Castelli, G.; Cohen, M.L.; Stamm, A.; et al. Subtype Diagnosis of Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease with Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchi, P.; Giese, A.; Capellari, S.; Brown, P.; Schulz-Schaeffer, W.; Windl, O.; Zerr, I.; Budka, H.; Kopp, N.; Piccardo, P.; et al. Classification of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Based on Molecular and Phenotypic Analysis of 300 Subjects. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 46, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchi, P.; Strammiello, R.; Notari, S.; Giese, A.; Langeveld, J.P.M.; Ladogana, A.; Zerr, I.; Roncaroli, F.; Cras, P.; Ghetti, B.; et al. Incidence and Spectrum of Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Variants with Mixed Phenotype and Co-Occurrence of PrPSc Types: An Updated Classification. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchi, P.; Strammiello, R.; Giese, A.; Kretzschmar, H. Phenotypic Variability of Sporadic Human Prion Disease and Its Molecular Basis: Past, Present, and Future. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyinszky, E.; Giau, V.V.; Youn, Y.C.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S. Characterization of Mutations in PRNP (Prion) Gene and Their Possible Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2067–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldelli, L.; Provini, F. Fatal Familial Insomnia and Agrypnia Excitata: Autonomic Dysfunctions and Pathophysiological Implications. Auton. Neurosci. 2019, 218, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovska, N.; Rusina, R.; Bruzova, M.; Parobkova, E.; Olejar, T.; Matej, R. Human Prion Disorders: Review of the Current Literature and a Twenty-Year Experience of the National Surveillance Center in the Czech Republic. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, L.T.; Kim, M.-O.; Cleveland, R.W.; Wong, K.; Forner, S.A.; Gala, I.I.; Fong, J.C.; Geschwind, M.D. Genetic Prion Disease: Experience of a Rapidly Progressive Dementia Center in the United States and a Review of the Literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 36–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, C.D.; Soldau, K.; Cordano, C.; Llibre-Guerra, J.; Green, A.J.; Sanchez, H.; Groveman, B.R.; Edland, S.D.; Safar, J.G.; Lin, J.H.; et al. Prion Seeds Distribute throughout the Eyes of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Patients. mBio 2018, 9, e02095-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, J. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Lancet 1999, 354, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewelyn, C.; Hewitt, P.; Knight, R.; Amar, K.; Cousens, S.; Mackenzie, J.; Will, R. Possible Transmission of Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease by Blood Transfusion. Lancet 2004, 363, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, K.J.; Correll, C.M. Prion Disease. Semin. Neurol. 2019, 39, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, J.; Whitfield, J.; McKintosh, E.; Beck, J.; Mead, S.; Thomas, D.J.; Alpers, M.P. Kuru in the 21st Century—An Acquired Human Prion Disease with Very Long Incubation Periods. Lancet 2006, 367, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, J.D.F.; Collinge, J. Molecular Pathology of Human Prion Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, M.-A.; Senatore, A.; Aguzzi, A. The Biological Function of the Cellular Prion Protein: An Update. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Lindquist, S. Wild-Type PrP and a Mutant Associated with Prion Disease Are Subject to Retrograde Transport and Proteasome Degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14955–14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsou, A.; Chen, P.-J.; Tsai, K.-W.; Hu, W.-C.; Lu, K.-C. THαβ Immunological Pathway as Protective Immune Response against Prion Diseases: An Insight for Prion Infection Therapy. Viruses 2022, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budka, H.; Aguzzi, A.; Brown, P.; Brucher, J.; Bugiani, O.; Gullotta, F.; Haltia, M.; Hauw, J.; Ironside, J.W.; Jellinger, K.; et al. Neuropathological Diagnostic Criteria for Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) and Other Human Spongiform Encephalopathies (Prion Diseases). Brain Pathol. 1995, 5, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, C.J.; Bartz, J.C.; Glatzel, M. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Prion Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019, 14, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, G.G.; Rahimi, J.; Ströbel, T.; Lutz, M.I.; Regelsberger, G.; Streichenberger, N.; Perret-Liaudet, A.; Höftberger, R.; Liberski, P.P.; Budka, H.; et al. Tau Pathology in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Revisited. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, S.; Capellari, S.; Ladogana, A.; Strumia, S.; Santangelo, M.; Pocchiari, M.; Parchi, P. Revisiting the Heidenhain Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Evidence for Prion Type Variability Influencing Clinical Course and Laboratory Findings. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 50, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladogana, A.; Puopolo, M.; Croes, E.A.; Budka, H.; Jarius, C.; Collins, S.; Klug, G.M.; Sutcliffe, T.; Giulivi, A.; Alperovitch, A.; et al. Mortality from Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and Related Disorders in Europe, Australia, and Canada. Neurology 2005, 64, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Baqai, M.H.; Naveed, H.; Naveed, T.; Rehman, S.S.; Aslam, M.S.; Lakdawala, F.M.; Memon, W.A.; Rani, S.; Khan, H.; et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Current Understanding and Research. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 467, 123293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Porcel, F.; Ciarlariello, V.B.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Lovera, L.; Da Prat, G.; Lopez-Castellanos, R.; Suri, R.; Laub, H.; Walker, R.H.; Barsottini, O.; et al. Movement Disorders in Prionopathies: A Systematic Review. Tremor Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 2019, 9, 10–7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, H.G.; Schindler, K.; Zumsteg, D. EEG in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, S.; Rudge, P. CJD Mimics and Chameleons. Pract. Neurol. 2017, 17, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, E.; Wehner, T.; Joly, O.; Lowe, J.; Porter, M.-C.; Kenny, J.; Thompson, A.; Rudge, P.; Collinge, J.; Mead, S. Quantitative EEG Parameters Correlate with the Progression of Human Prion Diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graus, F.; Titulaer, M.J.; Balu, R.; Benseler, S.; Bien, C.G.; Cellucci, T.; Cortese, I.; Dale, R.C.; Gelfand, J.M.; Geschwind, M.; et al. A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis of Autoimmune Encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.O.; Geschwind, M.D. Clinical update of Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, P.; Zerr, I. Rapidly Progressive Dementias—Aetiologies, Diagnosis and Management. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minikel, E.V.; Vallabh, S.M.; Orseth, M.C.; Brandel, J.-P.; Haïk, S.; Laplanche, J.-L.; Zerr, I.; Parchi, P.; Capellari, S.; Safar, J.; et al. Age at Onset in Genetic Prion Disease and the Design of Preventive Clinical Trials. Neurology 2019, 93, e125–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhi, D.; Yakub, F.; Sharma, K.; Waa, S.; Mativo, P. Heidenhain Variant of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: First Reported Case from East Africa. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2021, 14, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Redaelli, V.; Baiardi, S.; Mackenzie, G.; Windl, O.; Ritchie, D.L.; Didato, G.; Hernandez-Vara, J.; Rossi, M.; Capellari, S.; et al. Sporadic Fatal Insomnia in Europe: Phenotypic Features and Diagnostic Challenges. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 84, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, T.; Fischer, A.-L.; Canaslan, S.; Correia, S.D.S.; Hermann, P.; Schmitz, M.; Correia, A.D.S.; Zerr, I. Diagnosis of Prion Diseases. Subcell. Biochem. 2025, 112, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, B.; Kallenberg, K.; Sanchez-Juan, P.; Collie, D.; Summers, D.M.; Almonti, S.; Collins, S.J.; Smith, P.; Cras, P.; Jansen, G.H.; et al. MRI Lesion Profiles in Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. Neurology 2009, 72, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.S.; Geschwind, M.D.; Fischbein, N.J.; Martindale, J.L.; Henry, R.G.; Liu, S.; Lu, Y.; Wong, S.; Liu, H.; Miller, B.L.; et al. Diffusion-Weighted and Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery Imaging in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: High Sensitivity and Specificity for Diagnosis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Zerr, I.; Hermann, P. Diagnosis of Prion Disease: Conventional Approaches. In Prions and Diseases; Zou, W.-Q., Gambetti, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 675–701. ISBN 978-3-031-20564-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso, D.C.; Gonçalves Filho, A.L.D.M.; Pacheco, F.T.; Barros, B.R.; Aguiar Littig, I.; Nunes, R.H.; Maia Júnior, A.C.M.; Da Rocha, A.J. Imaging of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Imaging Patterns and Their Differential Diagnosis. RadioGraphics 2017, 37, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzi, A.; Pascuzzo, R.; Blevins, J.; Grisoli, M.; Lodi, R.; Moscatelli, M.E.M.; Castelli, G.; Cohen, M.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Foutz, A.; et al. Evaluation of a New Criterion for Detecting Prion Disease with Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, R.; Fragiacomo, F.; Ladogana, A.; Vaianella, L.; Camporese, G.; Zorzi, G.; Vicinanza, S.; Zanusso, G.; Pocchiari, M.; Cagnin, A. MRI Abnormalities in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and Other Rapidly Progressive Dementia. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Albizuri, C.; Erburu-Iriarte, M.; Gómez Muga, J.J.; Castillo-Calvo, B.; Hoyo-Santisteban, V.; Agirre-Castillero, J.; Garcia-Monco, J.C. Clinical Reasoning: A 59-Year-Old Man with Acute-Onset Encephalopathy and Aphasia. Neurology 2025, 105, e214299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R.W.; Torres-Chae, C.C.; Kuo, A.L.; Ando, T.; Nguyen, E.A.; Wong, K.; DeArmond, S.J.; Haman, A.; Garcia, P.; Johnson, D.Y.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Jakob-Creutzfeldt Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikonstantinou, S.; Kazis, D.; Karantali, E.; Knights, M.; McKenna, J.; Petridis, F.; Mavroudis, I. A Meta-Analysis on RT-QuIC for the Diagnosis of Sporadic CJD. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2021, 121, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundlamurri, R.; Shah, R.; Adiga, M.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Gautham, B.; Raghavendra, K.; Ajay, A.; Mahadevan, A.; Kulanthaivelu, K.; Sinha, S. EEG Observations in Probable Sporadic CJD. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2020, 23, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, N.; Hermann, P.; Ladogana, A.; Denouel, A.; Baiardi, S.; Colaizzo, E.; Giaccone, G.; Glatzel, M.; Green, A.J.E.; Haïk, S.; et al. Validation of Revised International Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Network Diagnostic Criteria for Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2146319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, P.; Schmitz, M.; Cramm, M.; Goebel, S.; Bunck, T.; Schütte-Schmidt, J.; Schulz-Schaeffer, W.; Stadelmann, C.; Matschke, J.; Glatzel, M.; et al. Application of Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Surveillance. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M.; Wiltfang, J.; Cepek, L.; Neumann, M.; Mollenhauer, B.; Steinacker, P.; Ciesielczyk, B.; Schulz–Schaeffer, W.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; Poser, S. Tau Protein and 14-3-3 Protein in the Differential Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. Neurology 2002, 58, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, H.C.; Fraser, J.R.; Liu, W.-G.; Forster, J.L.; Clokie, S.; Steinacker, P.; Otto, M.; Bahn, E.; Wiltfang, J.; Aitken, A. Specific 14-3-3 Isoform Detection and Immunolocalization in Prion Diseases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutz, A.; Appleby, B.S.; Hamlin, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Cohen, Y.; Chen, W.; Blevins, J.; Fausett, C.; Wang, H.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Human Prion Detection in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrú, C.D.; Groveman, B.R.; Hughson, A.G.; Zanusso, G.; Coulthart, M.B.; Caughey, B. Rapid and Sensitive RT-QuIC Detection of Human Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Using Cerebrospinal Fluid. mBio 2015, 6, e02451-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, T.H.; Nihat, A.; Majbour, N.; Sequeira, D.; Holm-Mercer, L.; Coysh, T.; Darwent, L.; Batchelor, M.; Groveman, B.R.; Orr, C.D.; et al. Seed Amplification and Neurodegeneration Marker Trajectories in Individuals at Risk of Prion Disease. Brain 2023, 146, 2570–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, M.; Schmitz, M.; Karch, A.; Mitrova, E.; Kuhn, F.; Schroeder, B.; Raeber, A.; Varges, D.; Kim, Y.-S.; Satoh, K.; et al. Stability and Reproducibility Underscore Utility of RT-QuIC for Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1896–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrú, C.D.; Groveman, B.R.; Foutz, A.; Bongianni, M.; Cardone, F.; McKenzie, N.; Culeux, A.; Poleggi, A.; Grznarova, K.; Perra, D.; et al. Ring Trial of 2nd Generation RT-QuIC Diagnostic Tests for Sporadic CJD. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 2262–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, R.; Satoh, K.; Sano, K.; Fuse, T.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ishibashi, D.; Matsubara, T.; Nakagaki, T.; Yamanaka, H.; Shirabe, S.; et al. Ultrasensitive Human Prion Detection in Cerebrospinal Fluid by Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, H.; Ueda, N.; Tanaka, F. The Advances in the Early and Accurate Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and Other Prion Diseases: Where Are We Today? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2023, 23, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, I.; Schmitz, M.; Karch, A.; Villar-Piqué, A.; Kanata, E.; Golanska, E.; Díaz-Lucena, D.; Karsanidou, A.; Hermann, P.; Knipper, T.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Levels in Neurodegenerative Dementia: Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy in the Differential Diagnosis of Prion Diseases. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Capellari, S.; Stanzani-Maserati, M.; Polischi, B.; Martinelli, P.; Caroppo, P.; Ladogana, A.; Parchi, P. The CSF Neurofilament Light Signature in Rapidly Progressive Neurodegenerative Dementias. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, S.; Khalili-Shirazi, A.; Potter, C.; Mok, T.; Nihat, A.; Hyare, H.; Canning, S.; Schmidt, C.; Campbell, T.; Darwent, L.; et al. Prion Protein Monoclonal Antibody (PRN100) Therapy for Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease: Evaluation of a First-in-Human Treatment Programme. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, S.; Poulter, M.; Uphill, J.; Beck, J.; Whitfield, J.; Webb, T.E.; Campbell, T.; Adamson, G.; Deriziotis, P.; Tabrizi, S.J.; et al. Genetic Risk Factors for Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease: A Genome-Wide Association Study. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, P.; Laux, M.; Glatzel, M.; Matschke, J.; Knipper, T.; Goebel, S.; Treig, J.; Schulz-Schaeffer, W.; Cramm, M.; Schmitz, M.; et al. Validation and Utilization of Amended Diagnostic Criteria in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance. Neurology 2018, 91, e331–e338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, I. Laboratory Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.T.; Gibbs, C.J. Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and Related Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Gálvez, S.; Goldfarb, L.G.; Nieto, A.; Cartier, L.; Gibbs, C.J.; Gajdusek, D.C. Familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in Chile Is Associated with the Codon 200 Mutation of the PRNP Amyloid Precursor Gene on Chromosome 20. J. Neurol. Sci. 1992, 112, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, M.I.; Satoh, K. Challenges and Revisions in Diagnostic Criteria: Advancing Early Detection of Prion Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascovich, C.; Amorin, I.; Damian, A.; Langhain, M.; Sgarbi, N.; Ferrando, R. Multimodal Neuroimaging in a Case of Familial (G114V) Juvenile Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Presenting with Parkinsonism. Neurocase 2025, 31, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service (NHS). Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/creutzfeldt-jakob-disease-cjd/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- De Bruijn, M.A.A.M.; Leypoldt, F.; Dalmau, J.; Lee, S.-T.; Honnorat, J.; Clardy, S.L.; Irani, S.R.; Easton, A.; Kunchok, A.; Titulaer, M.J. Autoimmune Encephalitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2025, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M.; Dubey, D.; Liebo, G.B.; Flanagan, E.P.; Britton, J.W. Clinical Course and Features of Seizures Associated with LGI1-Antibody Encephalitis. Neurology 2021, 97, e1141–e1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasp, M.; Dalmau, J. Autoimmune Encephalitis. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 109, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Maqueda, J.M.; Planagumà, J.; Guasp, M.; Dalmau, J. Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Manifesting with Psychosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e196507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, K.C.; Glaser, C.; Gaston, D.; Venkatesan, A. State of the Art: Acute Encephalitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, e14–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawada, J. Neurological Disorders Associated with Human Alphaherpesviruses. In Human Herpesviruses; Kawaguchi, Y., Mori, Y., Kimura, H., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 1045, pp. 85–102. ISBN 978-981-10-7229-1. [Google Scholar]

- Olie, S.E.; Staal, S.L.; Van De Beek, D.; Brouwer, M.C. Diagnosing Infectious Encephalitis: A Narrative Review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 67, e1–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.L. Acute Viral Encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Dash, U.; Tripathi, A.; Mazumdar, D.; Podh, D.; Singh, S. Hepatic Encephalopathy: Insights into the Impact of Metabolic Precipitates. Dev. Neurobiol. 2025, 85, e22999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Burlina, A.; Chakrapani, A.; Dixon, M.; Karall, D.; Lindner, M.; Mandel, H.; Martinelli, D.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Santer, R.; et al. Suggested Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Urea Cycle Disorders: First Revision. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 1192–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.P.; Tadevosyan, A.; Burns, J.D. Toxin-Induced Subacute Encephalopathy. Neurol. Clin. 2020, 38, 799–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvarani, C.; Hunder, G.G.; Brown, R.D. Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducros, A. Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewirtz, A.N.; Gao, V.; Parauda, S.C.; Robbins, M.S. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2021, 25, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvarani, C.; Brown, R.D.; Hunder, G.G. Adult Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.P. Paraneoplastic Disorders of the Nervous System. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 4899–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, M.D.; Murray, K. Differential diagnosis with other rapid progressive dementias in human prion diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 153, 371–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; Villagrán-García, M.; Vogrig, A.; Zekeridou, A.; Muñiz-Castrillo, S.; Velasco, R.; Guidon, A.C.; Joubert, B.; Honnorat, J. Neurological Adverse Events of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and the Development of Paraneoplastic Neurological Syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graus, F.; Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic Neurological Syndromes in the Era of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedeler, C.A.; Antoine, J.C.; Giometto, B.; Graus, F.; Grisold, W.; Hart, I.K.; Honnorat, J.; Sillevis Smitt, P.A.E.; Verschuuren, J.J.G.M.; Voltz, R.; et al. Management of Paraneoplastic Neurological Syndromes: Report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, D.A.; Lee, D.W. Cytokine Release Syndrome Biology and Management. Cancer J. 2021, 27, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, B.J.A.P.; Castrillo, B.B.; Alvim, R.P.; De Brito, M.H.; Gomes, H.R.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Smid, J.; Nitrini, R.; Landemberger, M.C.; Martins, V.R.; et al. Second-Generation RT-QuIC Assay for the Diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Patients in Brazil. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichet, G.; Comoy, E.; Duval, C.; Antloga, K.; Dehen, C.; Charbonnier, A.; McDonnell, G.; Brown, P.; Ida Lasmézas, C.; Deslys, J.-P. Novel Methods for Disinfection of Prion-Contaminated Medical Devices. Lancet 2004, 364, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.D.; Rhinehart, E.; Jackson, M.; Chiarello, L. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am. J. Infect. Control 2007, 35, S65–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayakumar, S.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. A Review on Current Theories and Potential Therapies for Prion Diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, B.S.; Yobs, D.R. Symptomatic treatment, care, and support of CJD patients. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 153, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, M.D.; Kuo, A.L.; Wong, K.S.; Haman, A.; Devereux, G.; Raudabaugh, B.J.; Johnson, D.Y.; Torres-Chae, C.C.; Finley, R.; Garcia, P.; et al. Quinacrine Treatment Trial for Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Neurology 2013, 81, 2015–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, J.; Gorham, M.; Hudson, F.; Kennedy, A.; Keogh, G.; Pal, S.; Rossor, M.; Rudge, P.; Siddique, D.; Spyer, M.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Quinacrine in Human Prion Disease (PRION-1 Study): A Patient-Preference Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, A.; Tagliavini, F.; Forloni, G.; Bate, C.; Salmona, M.; Colombo, L.; De Luigi, A.; Limido, L.; Suardi, S.; Rossi, G.; et al. Evaluation of Quinacrine Treatment for Prion Diseases. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 8462–8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forloni, G.; Iussich, S.; Awan, T.; Colombo, L.; Angeretti, N.; Girola, L.; Bertani, I.; Poli, G.; Caramelli, M.; Grazia Bruzzone, M.; et al. Tetracyclines Affect Prion Infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10849–10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forloni, G.; Salmona, M.; Marcon, G.; Tagliavini, F. Tetracyclines and Prion Infectivity. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2009, 9, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masone, A.; Zucchelli, C.; Caruso, E.; Musco, G.; Chiesa, R. Therapeutic Targeting of Cellular Prion Protein: Toward the Development of Dual Mechanism Anti-Prion Compounds. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallucci, G.; Dickinson, A.; Linehan, J.; Klöhn, P.-C.; Brandner, S.; Collinge, J. Depleting Neuronal PrP in Prion Infection Prevents Disease and Reverses Spongiosis. Science 2003, 302, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, A.S.L.F.; Lima, J.L.D.; Malta, M.C.S.; Marroquim, N.F.; Moreira, Á.R.; De Almeida Ladeia, I.; Dos Santos Cardoso, F.; Gonçalves, D.B.; Dutra, B.G.; Dos Santos, J.C.C. The Role of Microglia in Prion Diseases and Possible Therapeutic Targets: A Literature Review. Prion 2021, 15, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, M.L.; Biasini, E. Therapeutic Trajectories in Human Prion Diseases. Subcell. Biochem. 2025, 112, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, G.J.; Zhao, H.T.; Race, B.; Raymond, L.D.; Williams, K.; Swayze, E.E.; Graffam, S.; Le, J.; Caron, T.; Stathopoulos, J.; et al. Antisense Oligonucleotides Extend Survival of Prion-Infected Mice. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e131175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callista, V.A.; Hatware, K.V.; Ingle, P.V. Insights into the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Prion Diseases. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2025, 25, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, S.M.; Minikel, E.V.; Schreiber, S.L.; Lander, E.S. Towards a Treatment for Genetic Prion Disease: Trials and Biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinari, A.; Uliassi, E.; Bolognesi, M.L. New Therapeutic Modalities in Prion Diseases. Subcell. Biochem. 2025, 112, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lü, W.; Liu, L. New Implications for Prion Diseases Therapy and Prophylaxis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1324702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Noor, A.; Zerr, I. Therapies for Prion Diseases. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 165, pp. 47–58. ISBN 978-0-444-64012-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, P.; Zerr, I. Unmet Needs of Biochemical Biomarkers for Human Prion Diseases. Prion 2024, 18, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, S.; Mammana, A.; Capellari, S.; Parchi, P. Human Prion Disease: Molecular Pathogenesis, and Possible Therapeutic Targets and Strategies. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, A.H.; Day, L.W.; Muthusamy, V.R.; Collins, J.; Hambrick, R.D.; Brock, A.S.; Guda, N.M.; Buscaglia, J.M.; Petersen, B.T.; Buttar, N.S.; et al. ASGE Guideline for Infection Control during GI Endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C.; Kalomeris, T.; Li, Y.; Kubiak, J.; Racine-Brzostek, S.; SahBandar, I.; Zhao, Z.; Cushing, M.M.; Yang, H.S. Preanalytical Considerations of Handling Suspected Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Specimens Within the Clinical Pathology Laboratories: A Survey-Based Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonda, D.J.; Manjila, S.; Mehndiratta, P.; Khan, F.; Miller, B.R.; Onwuzulike, K.; Puoti, G.; Cohen, M.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Cali, I. Human Prion Diseases: Surgical Lessons Learned from Iatrogenic Prion Transmission. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 41, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregori, L.; Serer, A.R.; McDowell, K.L.; Cervenak, J.; Asher, D.M. Rapid Testing for Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in Donors of Cornea. Transplantation 2017, 101, e120–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Rhoads, D.D.; Appleby, B.S. Human Prion Diseases. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, N.; Brandel, J.-P.; Green, A.; Hermann, P.; Ladogana, A.; Lindsay, T.; Mackenzie, J.; Pocchiari, M.; Smith, C.; Zerr, I.; et al. The Importance of Ongoing International Surveillance for Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease/Phenotype | PRNP Mutation | Typical Age of Onset | Clinical Features | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic CJD (GCJD) | E200K | 50–60 yrs | Rapid dementia, myoclonus | High-penetrance clusters (e.g., Israel, Slovakia) |

| V210I | 50–70 yrs | sCJD-like, rapid course | Common in Europe | |

| D178N (with 129V) | 40–60 yrs | CJD phenotype | Genotype determines phenotype | |

| T183A, R208H, R148H | Variable | sCJD-like | Rare mutations | |

| Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI) | D178N-129M | 30–60 yrs | Insomnia, dysautonomia, ataxia | Complete penetrance |

| Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) | P102L | 30–60 yrs | Ataxia, dysarthria, long course (years) | Classic GSS mutation |

| A117V | 30–50 yrs | Early cognitive decline + ataxia | ||

| F198S | 40–60 yrs | Cerebellar + extrapyramidal signs | ||

| Other rare PRNP mutations | E196A, E196K, Y163X (truncation), Q160X | Variable | Highly heterogeneous | Some cause prion amyloidosis |

| Stop-codon mutations (PRNP truncations) | Y145X, Q160X, Y226X, Q227X | 20–60 yrs | Amyloidosis, chronic course | Often systemic PrP deposition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bellini, P.; Ruggiero, F.; Benedetti, A.; Cereda, C.W.; Gobbi, C.; Bianco, G.; Bongiovanni, M. Human Prion Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Public Health. Viruses 2026, 18, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020216

Bellini P, Ruggiero F, Benedetti A, Cereda CW, Gobbi C, Bianco G, Bongiovanni M. Human Prion Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Public Health. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020216

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellini, Paola, Francesco Ruggiero, Andrea Benedetti, Carlo W. Cereda, Claudio Gobbi, Giovanni Bianco, and Marco Bongiovanni. 2026. "Human Prion Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Public Health" Viruses 18, no. 2: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020216

APA StyleBellini, P., Ruggiero, F., Benedetti, A., Cereda, C. W., Gobbi, C., Bianco, G., & Bongiovanni, M. (2026). Human Prion Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Public Health. Viruses, 18(2), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020216