Development of a Novel Human Hepatoma Cell Line Supporting the Replication of a Recombinant HBV Genome with a Reporter Gene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid

2.2. Cells

2.3. Production of HBVcc

2.4. HiBiT Assay

2.5. Reagents

2.6. Southern Blot Analysis

2.7. Quantification of Extracellular HBV-DNA

2.8. Quantification of PreS Antigen and HBcAg

2.9. Immunostaining

2.10. RNA-Seq Analysis

2.11. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.12. RNA-Seq Processing

2.13. Heatmap Visualization

2.14. Pre-Ranked GSEA (GO:BP)

3. Results

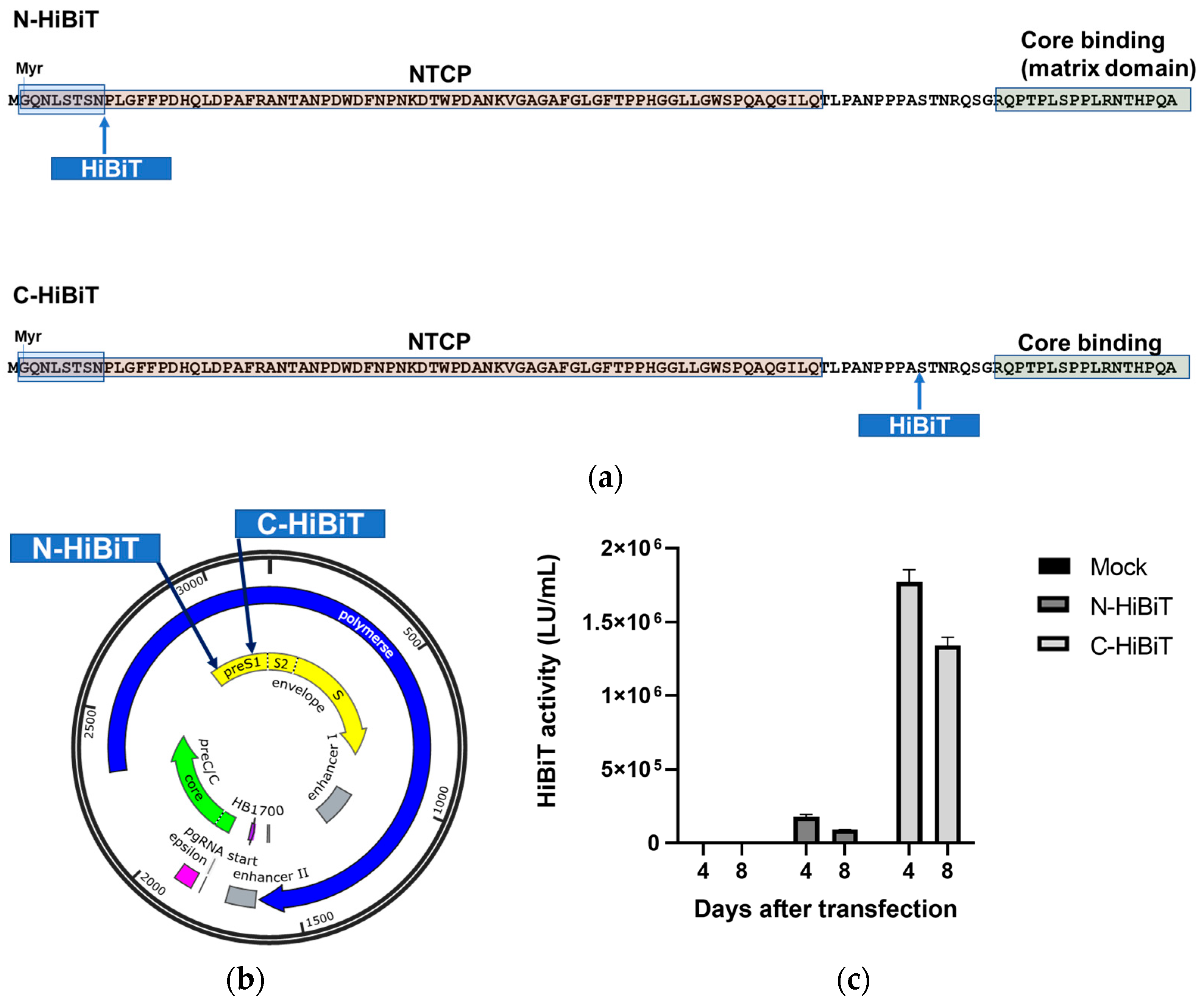

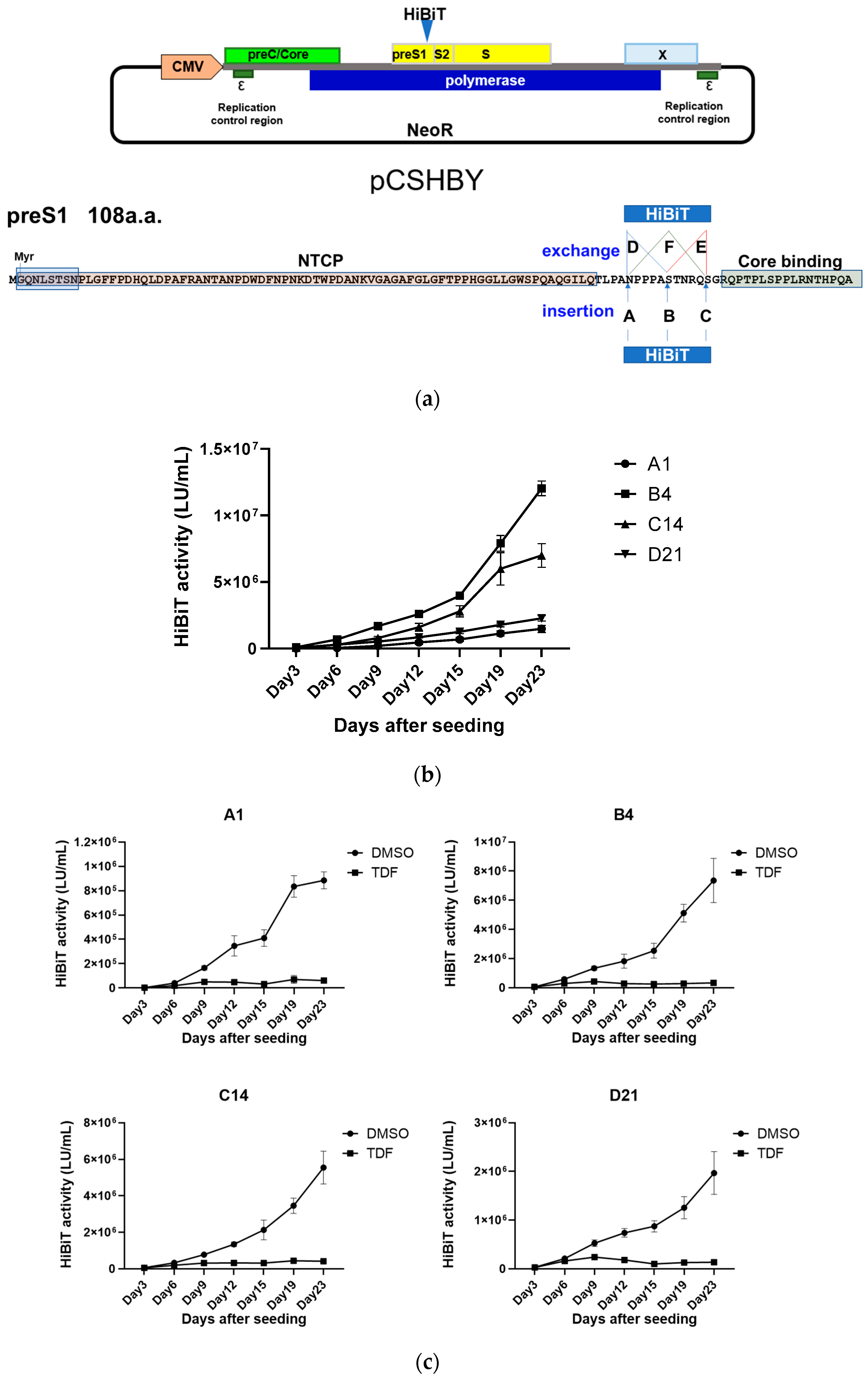

3.1. Establishment of the HepG2-B4 Cell Line

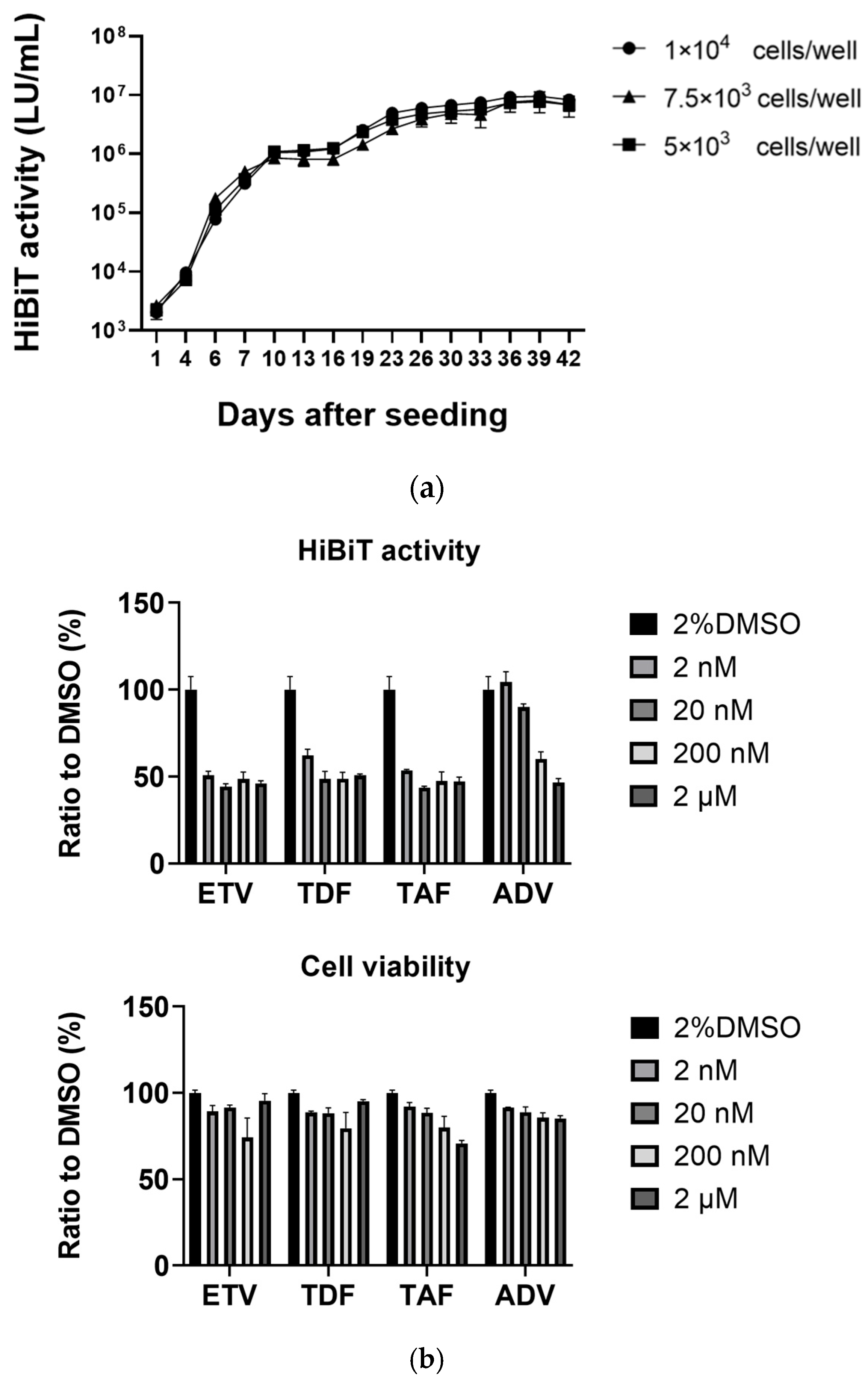

3.2. Long-Term Culture of HepG2-B4 Cells and the Effect of Nucleos(t)ide Analogs

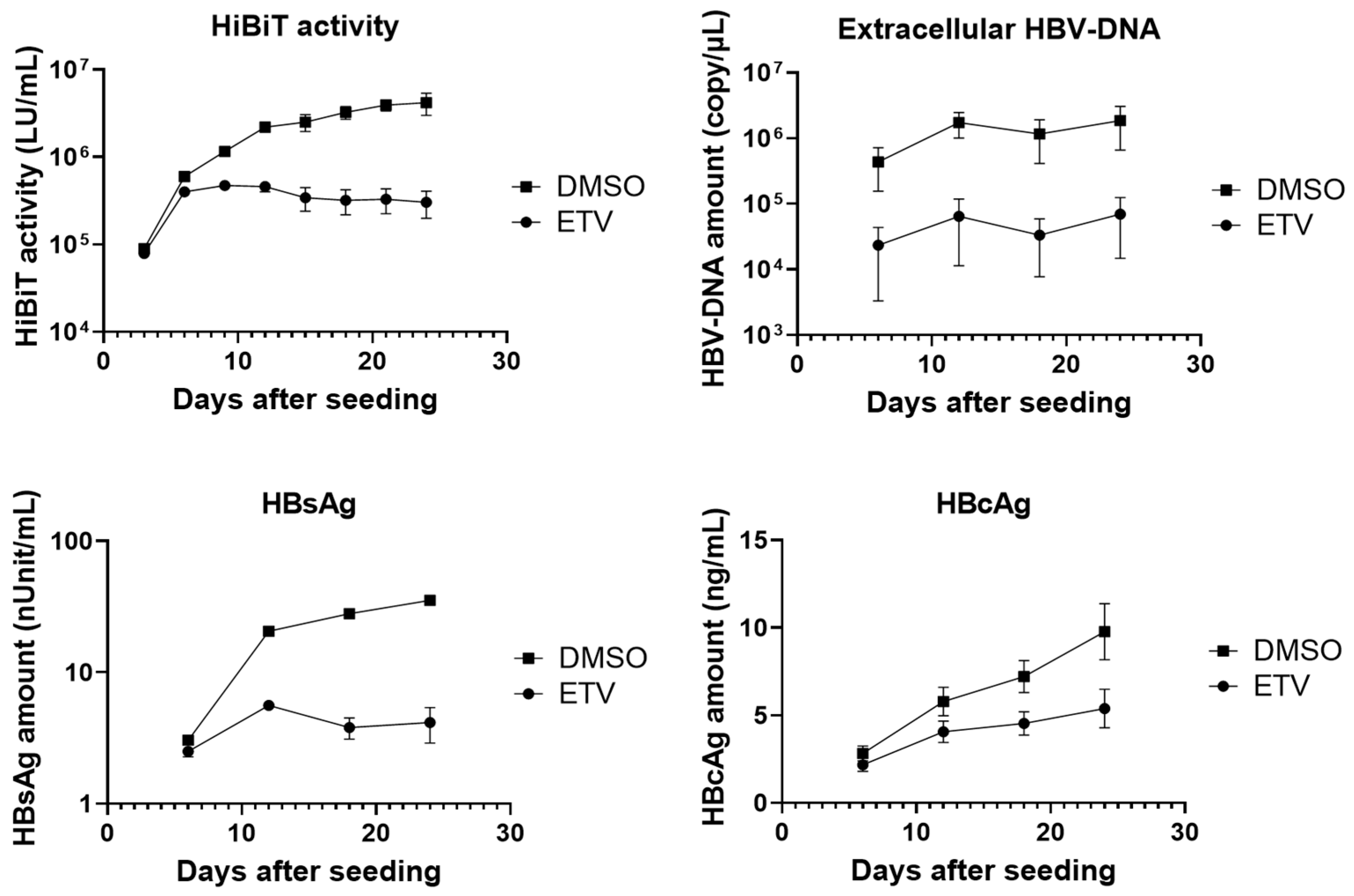

3.3. Extracellular HBV Markers

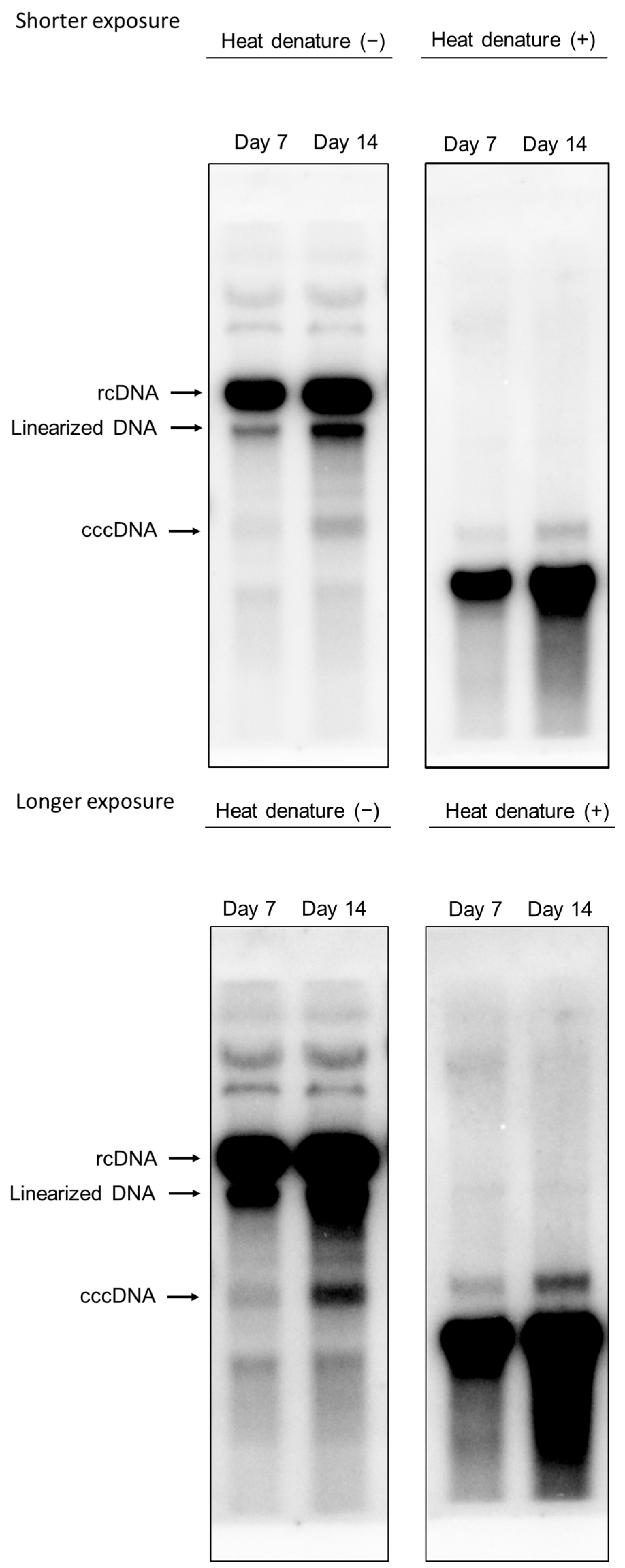

3.4. Intracellular HBV-DNA and cccDNA

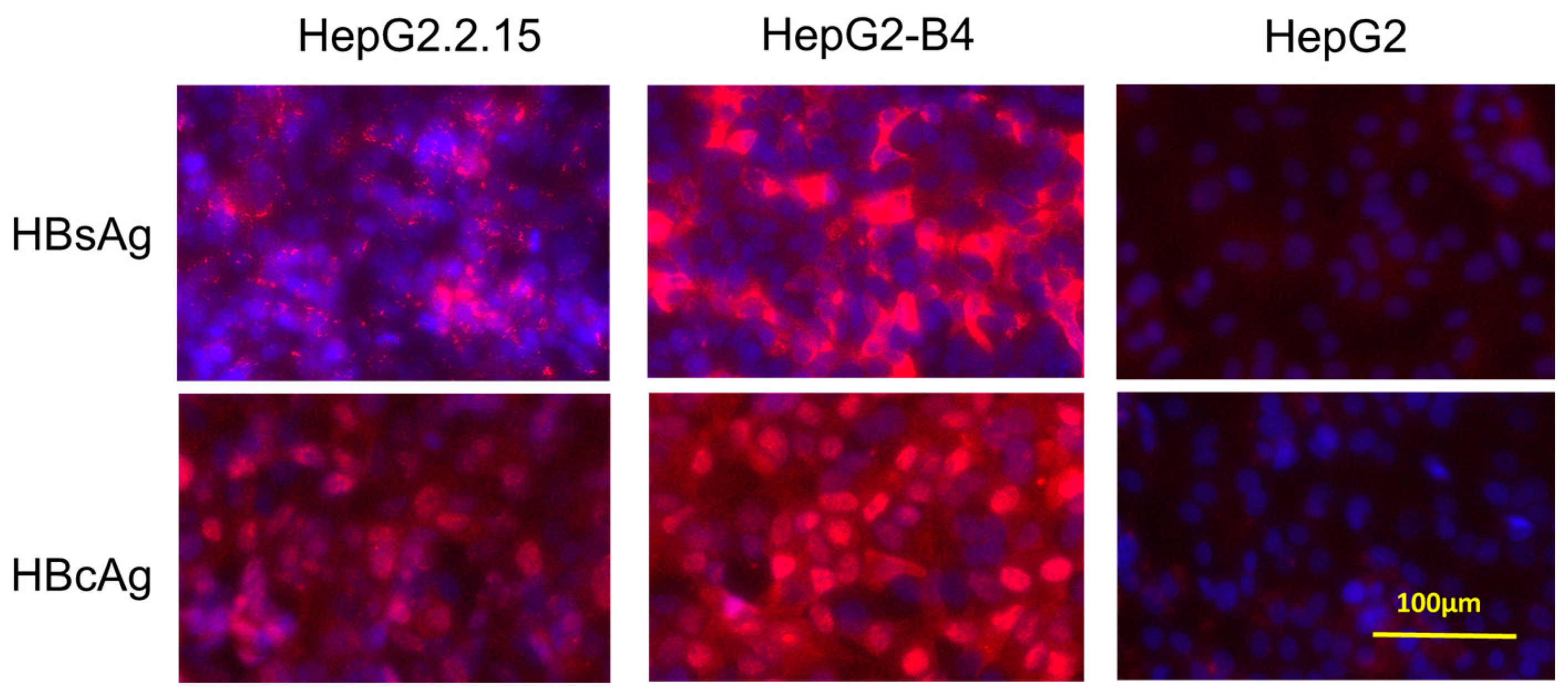

3.5. Immunostaining

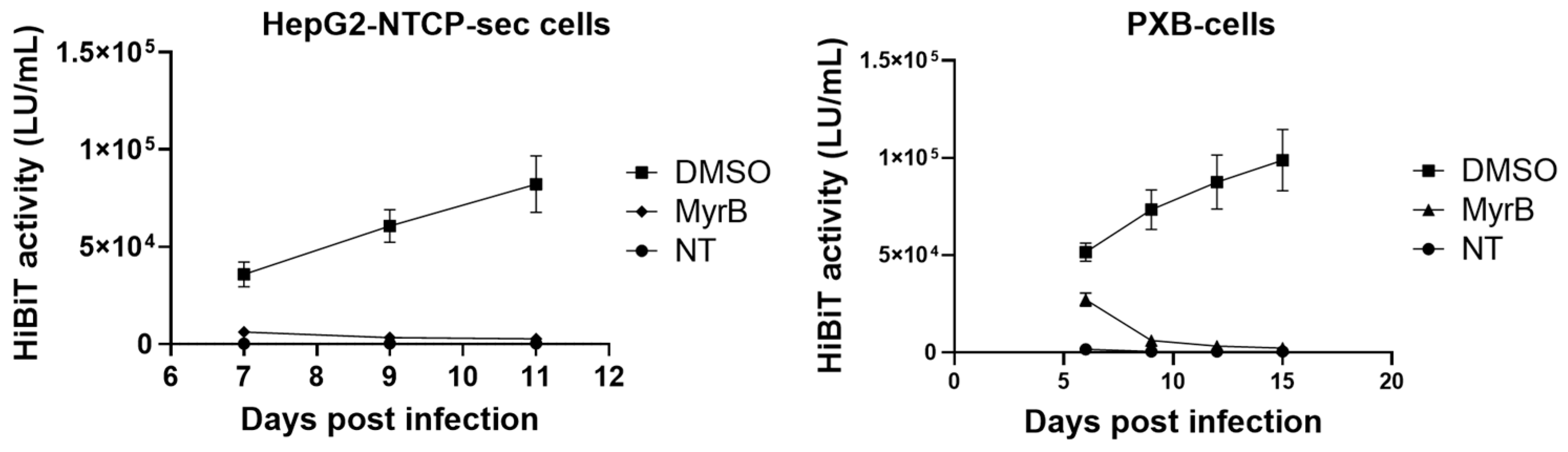

3.6. Infectivity of HiBiT-HBVcc from HepG2-B4 Cells

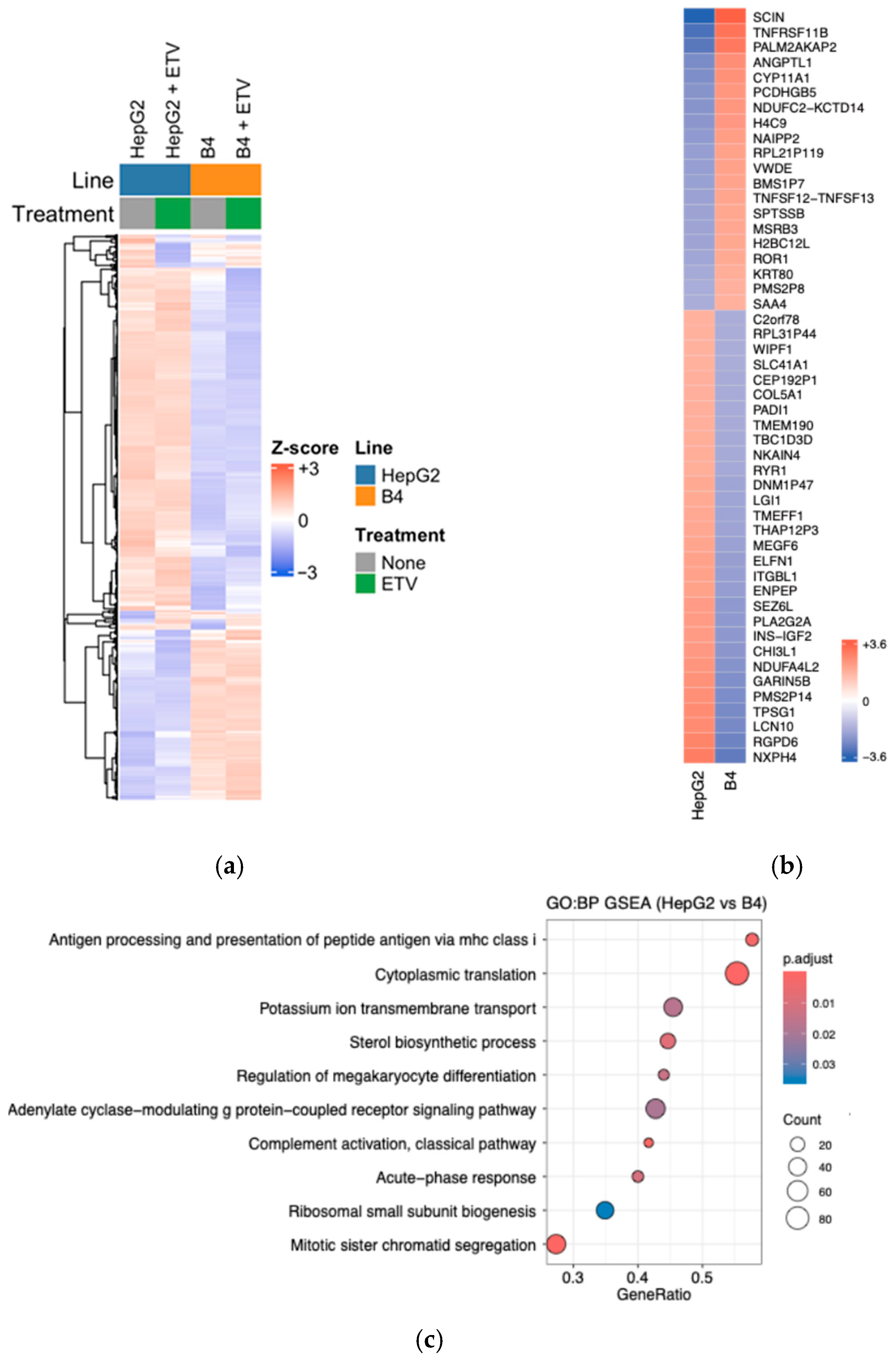

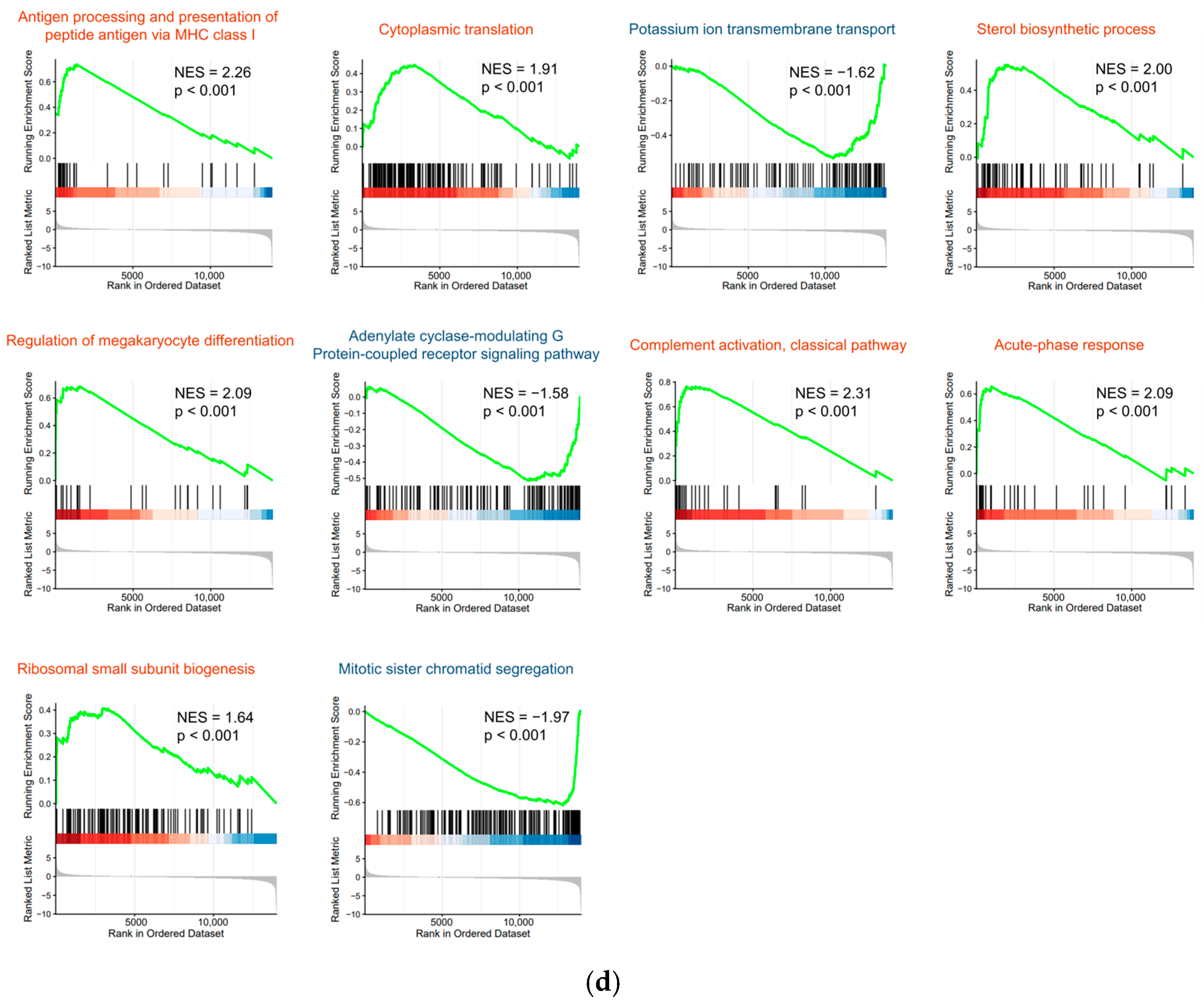

3.7. RNA-Seq Analysis of HepG2-B4 Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HBsAg | hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HBcAg | hepatitis B core antigen |

| cccDNA | covalently closed circular DNA |

| NTCP | sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide |

References

- Cui, F.; Blach, S.; Manzengo Mingiedi, C.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Sabry Alaama, A.; Mozalevskis, A.; Seguy, N.; Rewari, B.B.; Chan, P.L.; Le, L.V.; et al. Global reporting of progress towards elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, W.J.; Papatheodoridis, G.V.; Lok, A.S.F. Hepatitis B. Lancet 2023, 401, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari, R.; Nguyen, V.H.; Knoble, A.; Fricker, G.; Chung, R.T. Advances in the management of hepatitis B. BMJ 2025, 389, e079579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protzer, U.; Nassal, M.; Chiang, P.W.; Kirschfink, M.; Schaller, H. Interferon gene transfer by a hepatitis B virus vector efficiently suppresses wild-type virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10818–10823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; Jeng, K.S.; Hu, C.P.; Chang, C. Effects of genomic length on translocation of hepatitis B virus polymerase-linked oligomer. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 9010–9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beames, B.; Lanford, R.E. Insertions within the hepatitis B virus capsid protein influence capsid formation and RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 6833–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, A.S.; Schwinn, M.K.; Hall, M.P.; Zimmerman, K.; Otto, P.; Lubben, T.H.; Butler, B.L.; Binkowski, B.F.; Machleidt, T.; Kirkland, T.A.; et al. NanoLuc Complementation Reporter Optimized for Accurate Measurement of Protein Interactions in Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, M.K.; Machleidt, T.; Zimmerman, K.; Eggers, C.T.; Dixon, A.S.; Hurst, R.; Hall, M.P.; Encell, L.P.; Binkowski, B.F.; Wood, K.V. CRISPR-Mediated Tagging of Endogenous Proteins with a Luminescent Peptide. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Uchida, T.; Ono, C.; Mori, H.; Sato, A.; Fauzyah, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Kurosu, T.; Setoh, Y.X.; et al. Characterization of Recombinant Flaviviridae Viruses Possessing a Small Reporter Tag. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01582-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiyadorj, A.; Murai, K.; Shimakami, T.; Kuroki, K.; Nishikawa, T.; Kakuya, M.; Yamada, A.; Wang, Y.; Ishida, A.; Shirasaki, T.; et al. A single hepatitis B virus genome with a reporter allows the entire viral life cycle to be monitored in primary human hepatocytes. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 2441–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, M.A.; Chen, M.L.; Acs, G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, A.; Yang, J.; Jo, E.; Park, K.H.P.; Kim, H.; Than, T.T.; Song, X.; Qi, X.; Dai, X.; Park, S.; et al. Efficient long-term amplification of hepatitis B virus isolates after infection of slow proliferating HepG2-NTCP cells. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Yamasaki, C.; Yanagi, A.; Yoshizane, Y.; Fujikawa, K.; Watashi, K.; Abe, H.; Wakita, T.; Hayes, C.N.; Chayama, K.; et al. Novel robust in vitro hepatitis B virus infection model using fresh human hepatocytes isolated from humanized mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, C.; Yoshizane, Y.; Saito, N.; Kataoka, M.; Utoh, R.; Yamasaki, C.; Tachibana, A.; Soeno, Y.; Asahina, K.; Hino, H.; et al. Near completely humanized liver in mice shows human-type metabolic responses to drugs. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 1967, 26, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, M.M.; Tadey, L.; Mammana, L.; Quarleri, J.F.; Campos, R.H.; Flichman, D.M. Biological Characterization of Hepatitis B virus Genotypes: Their Role in Viral Replication and Antigen Expression. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 758613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripon, P.; Le Seyec, J.; Rumin, S.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C. Myristylation of the hepatitis B virus large surface protein is essential for viral infectivity. Virology 1995, 213, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruss, V.; Hagelstein, J.; Gerhardt, E.; Galle, P.R. Myristylation of the large surface protein is required for hepatitis B virus in vitro infectivity. Virology 1996, 218, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, D.R.; Walsh, A.W.; Baldick, C.J.; Eggers, B.J.; Rose, R.E.; Levine, S.M.; Kapur, A.J.; Colonno, R.J.; Tenney, D.J. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus polymerase by entecavir. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3992–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinazi, R.F.; Bassit, L.; Clayton, M.M.; Sun, B.; Kohler, J.J.; Obikhod, A.; Arzumanyan, A.; Feitelson, M.A. Evaluation of single and combination therapies with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in vitro and in a robust mouse model supporting high levels of hepatitis B virus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 6186–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Xiong, S.; Yang, H.; Miller, M.; Delaney, W.E., 4th. In vitro susceptibility of adefovir-associated hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations to other antiviral agents. Antivir. Ther. 2007, 12, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, W.E., 4th; Ray, A.S.; Yang, H.; Qi, X.; Xiong, S.; Zhu, Y.; Miller, M.D. Intracellular metabolism and in vitro activity of tenofovir against hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2471–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechot, C.; Pourcel, C.; Louise, A.; Rain, B.; Tiollais, P. Presence of integrated hepatitis B virus DNA sequences in cellular DNA of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature 1980, 286, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edman, J.C.; Gray, P.; Valenzuela, P.; Rall, L.B.; Rutter, W.J. Integration of hepatitis B virus sequences and their expression in a human hepatoma cell. Nature 1980, 286, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Igarashi, H.; Yamada, N.; Aly, H.H.; Toyama, M.; Isogawa, M.; Shimakami, T.; Kato, T. Exploring the tolerable region for HiBiT tag insertion in the hepatitis B virus genome. mSphere 2024, 9, e00518-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, Y.; Onomura, D.; Hoshi, Y.; Yamagata, T.; Morita, H.; Okamoto, H.; Murata, K. Establishment of a Hepatitis B Virus Reporter System Harboring an HiBiT-Tag in the PreS2 Region. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladner, S.K.; Otto, M.J.; Barker, C.S.; Zaifert, K.; Wang, G.H.; Guo, J.T.; Seeger, C.; King, R.W. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: A novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitsuji, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Shiina, R.; Harada, K.; Ujino, S.; Shimotohno, K. Development of a Hepatitis B Virus Reporter System to Monitor the Early Stages of the Replication Cycle. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 120, e54849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Cui, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J. Engineering Hepadnaviruses as Reporter-Expressing Vectors: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Viruses 2016, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Cheng, X.; Liu, S.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Kang, F.; Wang, J.; Xia, H.; Ping, C.; et al. Replication-competent infectious hepatitis B virus vectors carrying substantially sized transgenes by redesigned viral polymerase translation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kawase, S.; Shimakami, T.; Kuroki, K.; Murai, K.; Funaki, M.; Yoshita, M.; Kakuya, M.; Suzuki, R.; Li, Y.-Y.; Gantumur, D.; et al. Development of a Novel Human Hepatoma Cell Line Supporting the Replication of a Recombinant HBV Genome with a Reporter Gene. Viruses 2026, 18, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020187

Kawase S, Shimakami T, Kuroki K, Murai K, Funaki M, Yoshita M, Kakuya M, Suzuki R, Li Y-Y, Gantumur D, et al. Development of a Novel Human Hepatoma Cell Line Supporting the Replication of a Recombinant HBV Genome with a Reporter Gene. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020187

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawase, Shotaro, Tetsuro Shimakami, Kazuyuki Kuroki, Kazuhisa Murai, Masaya Funaki, Mika Yoshita, Masaki Kakuya, Reo Suzuki, Ying-Yi Li, Dolgormaa Gantumur, and et al. 2026. "Development of a Novel Human Hepatoma Cell Line Supporting the Replication of a Recombinant HBV Genome with a Reporter Gene" Viruses 18, no. 2: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020187

APA StyleKawase, S., Shimakami, T., Kuroki, K., Murai, K., Funaki, M., Yoshita, M., Kakuya, M., Suzuki, R., Li, Y.-Y., Gantumur, D., Kawane, T., Matsumori, K., Nio, K., Kawaguchi, K., Takatori, H., Honda, M., & Yamashita, T. (2026). Development of a Novel Human Hepatoma Cell Line Supporting the Replication of a Recombinant HBV Genome with a Reporter Gene. Viruses, 18(2), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020187