First Record of Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aguas Brancas virus, a New Insect-Specific Virus Found in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

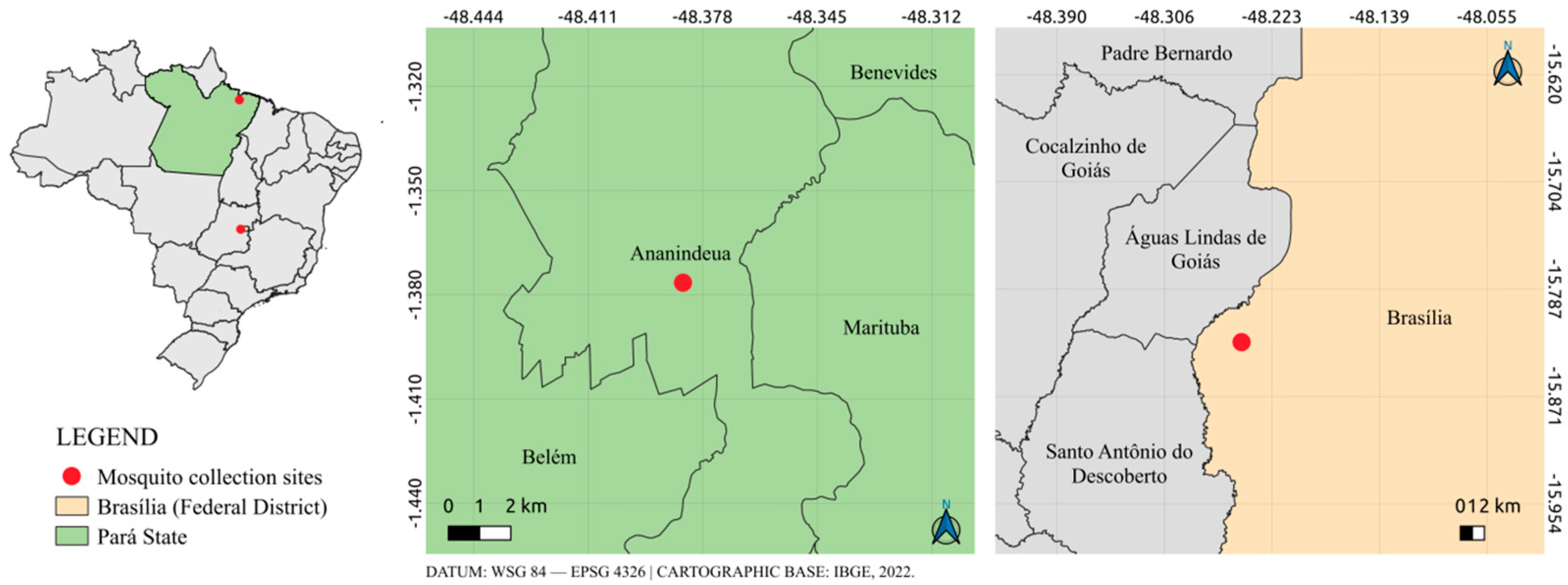

2.1. Mosquito Samples Collection

2.2. Routine Laboratory Diagnosis

2.3. Total RNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Data Processing

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial Diagnosis by Routine Laboratory Tests

3.2. Viral Genomes Obtained

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Paula Andrade, R. “Uma Floresta Cheia de Vírus!” Ciência e Desenvolvimento Nas Fronteiras Amazônicas. Rev. Bras. História 2019, 39, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, B.; Carvalho, V.; Silva, E.; Freitas, M.; Barros, L.J.; Santos, M.; Pantoja, J.A.; Gonçalves, E.; Nunes-Neto, J.; Rosa-Junior, J.W.; et al. The First Isolation of Insect-Specific Alphavirus (Agua Salud alphavirus) in Culex (Melanoconion) Mosquitoes in the Brazilian Amazon. Viruses 2024, 16, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilakis, N.; Guzman, H.; Firth, C.; Forrester, N.L.; Widen, S.G.; Wood, T.G.; Rossi, S.L.; Ghedin, E.; Popov, V.; Blasdell, K.R.; et al. Mesoniviruses Are Mosquito-Specific Viruses with Extensive Geographic Distribution and Host Range. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolling, B.G.; Weaver, S.C.; Tesh, R.B.; Vasilakis, N. Insect-Specific Virus Discovery: Significance for the Arbovirus Community. Viruses 2015, 7, 4911–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.L.; Long, M.T. Insect-Specific Viruses: An Overview and Their Relationship to Arboviruses of Concern to Humans and Animals. Virology 2021, 557, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stollar, V.; Thomas, V.L. An Agent in the Aedes Aegypti Cell Line (Peleg) Which Causes Fusion of Aedes Albopictus Cells. Virology 1975, 64, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, L.T.M. Emergent Arboviruses in Brazil. Rev. da Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2007, 40, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, N.; Nozawa, C.; Linhares, R.E.C. Características Gerais e Epidemiologia Dos Arbovírus Emergentes No Brasil. Rev. Pan-Amazônica Saúde 2014, 5, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhlund, P.; Lundén, H.; Blomström, A.L. Insect-Specific Virus Evolution and Potential Effects on Vector Competence. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forattini, O.P. Culicidologia Médica: Identificação, Biologia, Epidemiologia; Edusp: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Thangamani, S.; Huang, J.; Hart, C.E.; Guzman, H.; Tesh, R.B. Vertical Transmission of Zika Virus in Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 95, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travassos da Rosa, J.F.S.; Travassos da Rosa, A.P.A.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Pinheiro, F.; Travassos da Rosa, E.S.; Dias, L.B.; Cruz, A.C.R. Arboviruses Isolated in the Evandro Chagas Institute, Including Some Described for the Firs Time in the Brazilian Amazon Region, Their Known Host, and Their Pathology for Man. In An Overview of Arbovirology in Brazil and Neighbouring Countries; Instituto Evandro Chagas: Belem, Brazil, 1998; pp. 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gubler, D.J.; Velez, M.; Kuno, G.; Oliver, A.; Sather, G.E. Mosquito Cell Cultures and Specific Monoclonal Antibodies in Surveillance for Dengue Viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1984, 33, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Leung, H.C.M.; Yiu, S.M.; Chin, F.Y.L. IDBA-UD: A de Novo Assembler for Single-Cell and Metagenomic Sequencing Data with Highly Uneven Depth. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.G. Sensitive Protein Alignments at Tree-of-Life Scale Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-Scale Protein Function Classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. SeqKit: A Cross-Platform and Ultrafast Toolkit for FASTA/Q File Manipulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A Fast and Lightweight Alignment Viewer and Editor for Large Datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strimmer, K.; Von Haeseler, A. Likelihood-Mapping: A Simple Method to Visualize Phylogenetic Content of a Sequence Alignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 6815–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, G.; Chang, G.-J.J.; Tsuchiya, K.R.; Karabatsos, N.; Cropp, C.B. Phylogeny of the Genus Flavivirus. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P.; Adams, M.J.; Benkő, M.; Breitbart, M.; Brister, J.R.; Carstens, E.B.; Davison, A.J.; Delwart, E.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Harrach, B.; et al. Consensus Statement: Virus Taxonomy in the Age of Metagenomics. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 2017, 15, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S. NS3 Protease from Flavivirus as a Target for Designing Antiviral Inhibitors against Dengue Virus. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2010, 33, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zeng, M.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Jia, R.; Zhu, D.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Q.; et al. Flavivirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Interacts with Genome UTRs and Viral Proteins to Facilitate Flavivirus RNA Replication. Viruses 2019, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.-D.; Tian, J.-H.; Chen, L.-J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.-X.; Qin, X.-C.; Li, J.; Cao, J.-P.; Eden, J.-S.; et al. Redefining the Invertebrate RNA Virosphere. Nature 2016, 540, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multini, L.C.; Oliveira-Christe, R.; Medeiros-Sousa, A.R.; Evangelista, E.; Barrio-Nuevo, K.M.; Mucci, L.F.; Ceretti-Junior, W.; Camargo, A.A.; Wilke, A.B.; Marrelli, M.T. The Influence of the Ph and Salinity of Water in Breeding Sites on the Occurrence and Community Composition of Immature Mosquitoes in the Green Belt of the City of São Paulo, Brazil. Insects 2021, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multini, L.C.; Wilke, A.B.B.; Marrelli, M.T. Urbanization as a Driver for Temporal Wing-Shape Variation in Anopheles cruzii (Diptera: Culicidae). Acta Trop. 2019, 190, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrio-Nuevo, K.M.; Cunha, M.S.; Luchs, A.; Fernandes, A.; Rocco, I.M.; Mucci, L.F.; DE Souza, R.P.; Medeiros-Sousa, A.R.; Ceretti-Junior, W.; Marrelli, M.T. Detection of Zika and Dengue Viruses in Wildcaught Mosquitoes Collected during Field Surveillance in an Environmental Protection Area in São Paulo, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Vieira, A.R.; Gurgel-Gonçalves, R.; Moreira, I.M.; Yoshizawa, M.A.C.; Coutinho, M.L.; Prado, P.S.; de Souza, J.L.; Chaib, A.J.d.M.; Moreira, J.S.; de Castro, C.N. Ecological Aspects of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Gallery Forest of Brasília National Park, Brazil, with an Emphasis on Potential Vectors of Yellow Fever. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2013, 46, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G.G.; Rocha, M.N.; de Oliveira, M.A.; Moreira, L.A.; Andrade-Filho, J.D. Detection of Yellow Fever Virus in Sylvatic Mosquitoes during Disease Outbreaks of 2017–2018 in Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Insects 2019, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Triana, L.M.; Garza-Hernández, J.A.; Ortega Morales, A.I.; Prosser, S.W.J.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Nikolova, N.I.; Barrero, E.; de Luna-Santillana, E.d.J.; González-Alvarez, V.H.; Mendez-López, R.; et al. An Integrated Molecular Approach to Untangling Host–Vector–Pathogen Interactions in Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Sylvan Communities in Mexico. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 564791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Freitas, V.C.; Silva, F.S.d.; Dias, D.D.; Rosa Junior, J.W.; Nascimento, B.L.S.d.; Santos, M.M.; Silva, J.L.C.; Vieira, A.R.L.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Silva, S.P.d.; et al. First Record of Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aguas Brancas virus, a New Insect-Specific Virus Found in Brazil. Viruses 2026, 18, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020164

Freitas VC, Silva FSd, Dias DD, Rosa Junior JW, Nascimento BLSd, Santos MM, Silva JLC, Vieira ARL, Cruz ACR, Silva SPd, et al. First Record of Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aguas Brancas virus, a New Insect-Specific Virus Found in Brazil. Viruses. 2026; 18(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreitas, Valéria Cardoso, Fábio Silva da Silva, Daniel Damous Dias, José Wilson Rosa Junior, Bruna Laís Sena do Nascimento, Maissa Maia Santos, José Leimar Camelo Silva, Ana Raquel Lira Vieira, Ana Cecília Ribeiro Cruz, Sandro Patroca da Silva, and et al. 2026. "First Record of Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aguas Brancas virus, a New Insect-Specific Virus Found in Brazil" Viruses 18, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020164

APA StyleFreitas, V. C., Silva, F. S. d., Dias, D. D., Rosa Junior, J. W., Nascimento, B. L. S. d., Santos, M. M., Silva, J. L. C., Vieira, A. R. L., Cruz, A. C. R., Silva, S. P. d., Casseb, L. M. N., Nunes Neto, J. P., & Carvalho, V. L. (2026). First Record of Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aguas Brancas virus, a New Insect-Specific Virus Found in Brazil. Viruses, 18(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18020164