Validation of Chemical Inactivation Protocols for Henipavirus-Infected Tissue Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

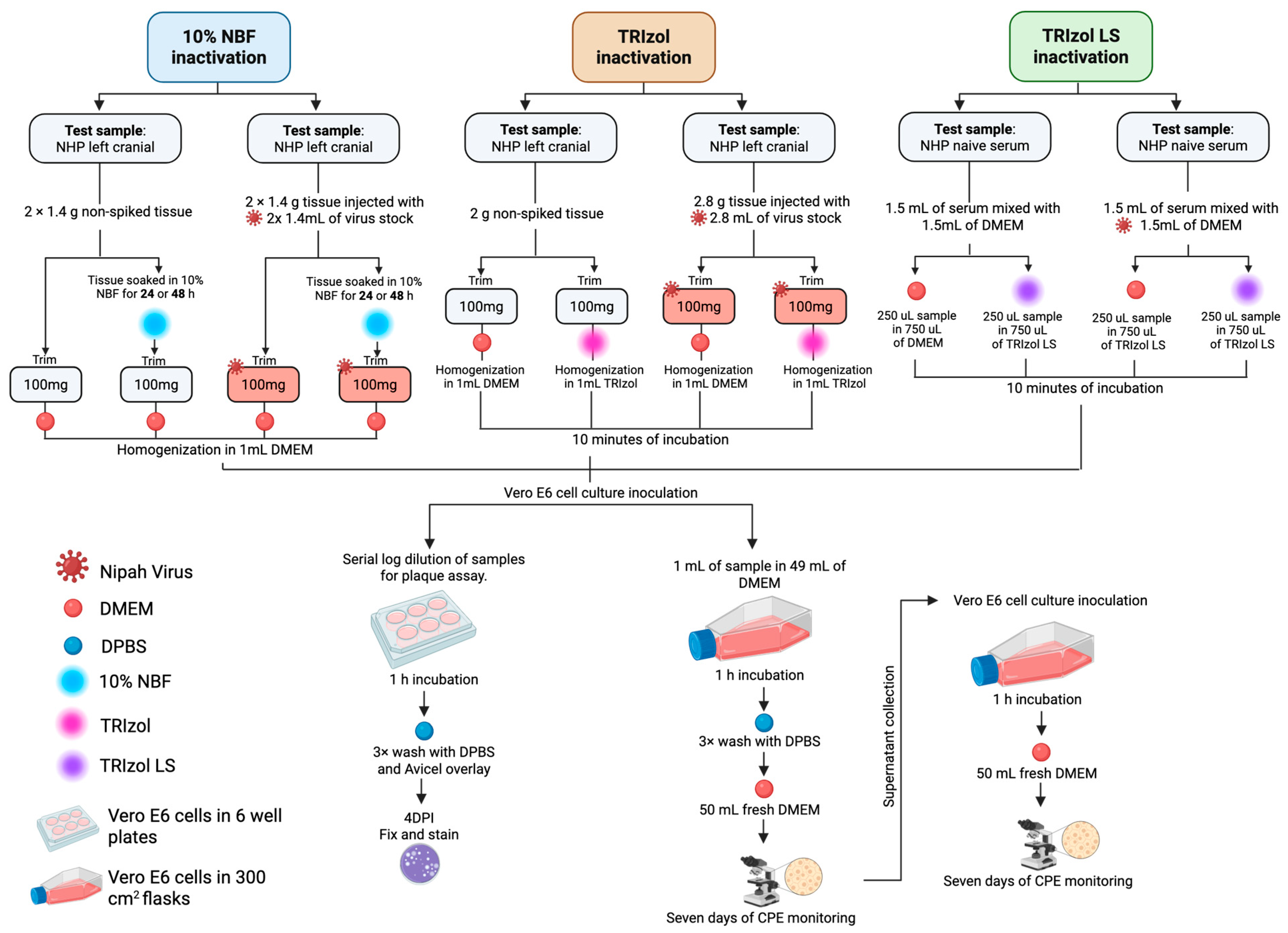

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Cells and Virus

2.3. Determination of Limit of Detection

2.4. Chemical Inactivation of NiV-Infected Samples

2.4.1. 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin

2.4.2. TRIzol Reagent

2.4.3. TRIzol LS Reagent

2.5. Determination of Viral Titer by Plaque Assay

2.6. Analysis of Samples After Inactivation

2.7. Assessing Inactivation Reagent Cytotoxicity and Impact on Virus Infection

3. Results

3.1. Limit of Detection Determination

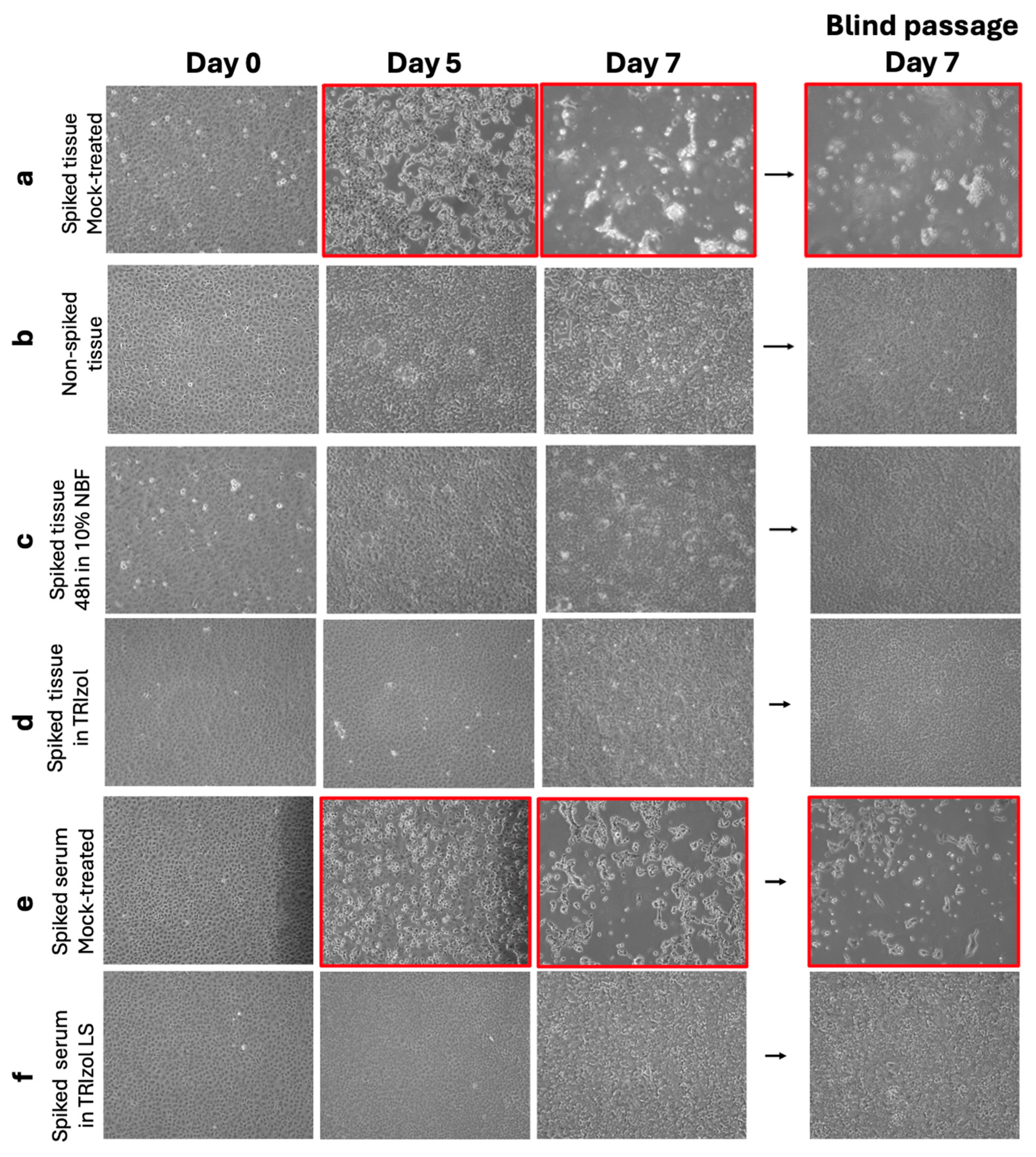

3.2. Treatment with 10% NBF of NiV-Spiked Tissue Samples Inactivates NiV Infectious Particles

3.3. TRIzol Treatment of NiV-Spiked Tissue Samples Inactivates NiV Infectious Particles

3.4. Serum Samples Spiked with NiV Were Inactivated After TRIzol LS Reagent Treatment

3.5. Inactivation Reagents Used in This Study Do Not Have a Cytotoxic Effect in Cells and Do Not Affect Cells’ Susceptibility and Permissibility to NiV Infection

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Select Agents and Toxins Program. Select Agents and Toxins List. Available online: https://www.selectagents.gov/sat/list.htm (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- CDC; APHIS. Guidance on the Inactivation or Removal of Select Agents and Toxins or Future Use; 7 CFR Part 331, 9 CFR Part 121.3, 42 CFR Part 73.3; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Select Agents and Toxins (DSAT): Atlanta, GA, USA; Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), Division of Agricultural Select Agents and Toxins (DASAT): Riverdale, MD, USA, 2018.

- Spengler, J.R.; Lo, M.K.; Welch, S.R.; Spiropoulou, C.F. Henipaviruses: Epidemiology, ecology, disease, and the development of vaccines and therapeutics. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 38, e00128-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaza, B.; Aguilar, H.C. Pathogenicity and virulence of henipaviruses. Virulence 2023, 14, 2273684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, H.; Kim, J.V.; Pickering, B.S. Henipavirus zoonosis: Outbreaks, animal hosts and potential new emergence. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1167085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kochel, T.J.; Kocher, G.A.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Burans, J.P. Evaluation of TRIzol LS inactivation of viruses. Appl. Biosaf. 2017, 22, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.; Nappo, M.A.; Ferrari, L.; Di Lecce, R.; Guarnieri, C.; Cantoni, A.M.; Corradi, A. Nipah Virus Disease: Epidemiological, Clinical, Diagnostic and Legislative Aspects of This Unpredictable Emerging Zoonosis. Animals 2023, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branda, F.; Ceccarelli, G.; Giovanetti, M.; Albanese, M.; Binetti, E.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Nipah Virus: A Zoonotic Threat Re-Emerging in the Wake of Global Public Health Challenges. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, F.; Shupert, W.L.; Haddock, E.; Twardoski, B.; Feldmann, H. Gamma irradiation as an effective method for inactivation of emerging viral pathogens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smither, S.J.; Eastaugh, L.S.; O’Brien, L.M.; Phelps, A.L.; Lever, M.S. Aerosol Survival, Disinfection and Formalin Inactivation of Nipah Virus. Viruses 2022, 14, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholte, F.E.M.; Kabra, K.B.; Tritsch, S.R.; Montgomery, J.M.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Mores, C.N.; Harcourt, B.H. Exploring inactivation of SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, Ebola, Lassa, and Nipah viruses on N95 and KN95 respirator material using photoactivated methylene blue to enable reuse. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Song, D.; Yuan, Z. Evaluation and comparison of three virucidal agents on inactivation of Nipah virus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickmann, M.; Gravemann, U.; Handke, W.; Tolksdorf, F.; Reichenberg, S.; Müller, T.H.; Seltsam, A. Inactivation of three emerging viruses—Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Nipah virus—In platelet concentrates by ultraviolet C light and in plasma by methylene blue plus visible light. Vox Sang. 2020, 115, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejnik, J.; Hume, A.J.; Ross, S.J.; Scoon, W.A.; Seitz, S.; White, M.R.; Slutzky, B.; Yun, N.E.; Mühlberger, E. Art of the Kill: Designing and Testing Viral Inactivation Procedures for Highly Pathogenic Negative Sense RNA Viruses. Pathogens 2023, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Fukushi, S.; Harada, T.; Shimojima, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kurosu, T.; Kaku, Y.; Morikawa, S.; Saijo, M. Effective inactivation of Nipah virus in serum samples for safe processing in low-containment laboratories. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S.J.; Caruso, S.; Suen, W.W.; Jackson, S.; Rowe, B.; Marsh, G.A. Evaluation of henipavirus chemical inactivation methods for the safe removal of samples from the high-containment PC4 laboratory. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 298, 114287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widerspick, L.; Vázquez, C.A.; Niemetz, L.; Heung, M.; Olal, C.; Bencsik, A.; Henkel, C.; Pfister, A.; Brunetti, J.E.; Kucinskaite-Kodze, I.; et al. Inactivation Methods for Experimental Nipah Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfson, K.J.; Griffiths, A. Development and Testing of a Method for Validating Chemical Inactivation of Ebola Virus. Viruses 2018, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geisbert, T.W.; Daddario-DiCaprio, K.M.; Hickey, A.C.; Smith, M.A.; Chan, Y.P.; Wang, L.F.; Mattapallil, J.J.; Geisbert, J.B.; Bossart, K.N.; Broder, C.C. Development of an Acute and Highly Pathogenic Nonhuman Primate Model of Nipah Virus Infection. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisbert, J.B.; Borisevich, V.; Prasad, A.N.; Agans, K.N.; Foster, S.L.; Deer, D.J.; Cross, R.W.; Mire, C.E.; Geisbert, T.W.; Fenton, K.A. An Intranasal Exposure Model of Lethal Nipah Virus Infection in African Green Monkeys. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, S414–S418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pigeaud, D.D.; Geisbert, T.W.; Woolsey, C. Animal Models for Henipavirus Research. Viruses 2023, 15, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Section | Treatment | mL | DMEM mL | Dilution Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 2.4.1 | 10% NBF | 1 | 49 | 0.02 |

| Section 2.4.2 | TRIzol | 1 | 49 | 0.02 |

| Section 2.4.3 | TRIzol LS | 0.75 | 49.25 | 0.015 |

| Sample | Treatment | Treatment Exposure Time | 5DPI CPE | 7DPI CPE | Blind Passage 7DPI CPE | Complete Inactivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mock Brain Tissue | None | NA | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Brain Tissue | None | NA | + | + | + | NA |

| Mock Brain Tissue | 10% NBF | 24 h, RT | − | − | − | NA |

| Mock Brain Tissue | 10% NBF | 24 h, RT | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Brain Tissue | 10% NBF | 48 h, RT | − | − | − | Yes |

| Spiked Brain Tissue | 10% NBF | 48 h, RT | − | − | − | Yes |

| Mock Brain Tissue | None | NA | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Brain Tissue | None | NA | + | + | + | NA |

| Mock Brain Tissue | TRIzol | 15 min, RT | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Brain Tissue | TRIzol | 15 min, RT | − | − | − | Yes |

| Mock Serum | None | NA | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Serum | None | NA | + | + | + | NA |

| Mock Serum | TRIzol LS | 15 min, RT | − | − | − | NA |

| Spiked Serum | TRIzol LS | 15 min, RT | − | − | − | Yes |

| Sample Nature | Inactivation Chemical | Amount of NiV |

|---|---|---|

| NHP tissues | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin | 4.6 × 105 PFU |

| NHP tissues | TRIzol reagent | 4.9 × 105 PFU |

| NHP serum | TRIzol LS reagent | 6.3 × 105 PFU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva-Ayala, D.; Griffiths, A. Validation of Chemical Inactivation Protocols for Henipavirus-Infected Tissue Samples. Viruses 2026, 18, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010081

Silva-Ayala D, Griffiths A. Validation of Chemical Inactivation Protocols for Henipavirus-Infected Tissue Samples. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva-Ayala, Daniela, and Anthony Griffiths. 2026. "Validation of Chemical Inactivation Protocols for Henipavirus-Infected Tissue Samples" Viruses 18, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010081

APA StyleSilva-Ayala, D., & Griffiths, A. (2026). Validation of Chemical Inactivation Protocols for Henipavirus-Infected Tissue Samples. Viruses, 18(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010081