Respiratory Viral Infection Prophylaxis and Treatment in the Transplant Population

Abstract

1. Introduction and Epidemiology

2. Influenza

2.1. Background

2.2. Vaccination

2.2.1. Available Vaccines

2.2.2. Timing

2.2.3. Efficacy and Safety

2.3. Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

2.4. Treatment

2.4.1. Neuraminidase Inhibitors

2.4.2. Cap-Dependent Endonuclease Inhibitors

2.4.3. CD388

3. SARS-CoV-2

3.1. Background

3.2. Vaccination

3.2.1. Available Vaccines

3.2.2. Timing

3.2.3. Efficacy and Safety

3.3. Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

3.4. Treatment

3.4.1. Remdesivir (Veklury, Gilead Sciences—Foster City, CA, USA)

3.4.2. Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer—New York City, NY, USA)

3.4.3. Molnupiravir (Lagevrio, Merck & Co., Ltd.—Rahway, NJ, USA)

3.4.4. Monoclonal Antibodies

4. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

4.1. Background

4.2. Vaccination

4.2.1. Available Vaccines

4.2.2. Timing

4.2.3. Efficacy and Safety

4.3. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

4.4. Treatment

4.4.1. Ribavirin

4.4.2. Molnupiravir (Lagevrio, Merck & Co., Ltd.—Rahway, NJ, USA)

5. Other Respiratory Viruses

5.1. Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

5.2. Rhinovirus/Enterovirus

5.3. Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV)

5.4. Adenovirus (HAdV)

5.5. Non-COVID Human Coronavirus (HCoV)

5.6. Non-RSV Paramyxoviridae (e.g., Parainfluenza [PIV])

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RVI | Respiratory viral infection |

| SOT | Solid organ transplant |

| HCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

| SOTR | Solid organ transplant recipient |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

References

- Mombelli, M.; Lang, B.; Neofytos, D.; Aubert, J.; Benden, C.; Berger, C.; Boggian, K.; Egli, A.; Soccal, P.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Burden, epidemiology, and outcomes of microbiologically confirmed respiratory viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients: A nationwide, multi-season prospective cohort study. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2021, 21, 1789–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Gómez, D.; Montoro, J.; Chorão, P.; Hernani, R.; Guerriero, M.; Villalba, M.; Albert, E.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Hernández-Boluda, J.C.; et al. Are any specific respiratory viruses more severe than others in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantation? A focus on lower respiratory tract disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024, 59, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, O.; Estabrook, M.; American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. RNA respiratory viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofzinger, T.B.; Huang, T.T.; Lingat, C.E.R.; Amonkar, G.M.; Edwards, E.E.; Yu, A.; Smith, A.D.; Gayed, N.; Gaddey, H. Vaccine fatigue and influenza vaccination trends across Pre-, Peri-, and Post-COVID-19 periods in the United States using epic’s cosmos database. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, M.; Hugentobler, W.J.; Iwasaki, A. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020, 7, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemken, T.L.; Khan, F.; Puzniak, L.; Yang, W.; Simmering, J.; Polgreen, P.; Nguyen, J.L.; Jodar, L.; McLaughlin, J.M. Seasonal trends in COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and mortality in the United States and Europe. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

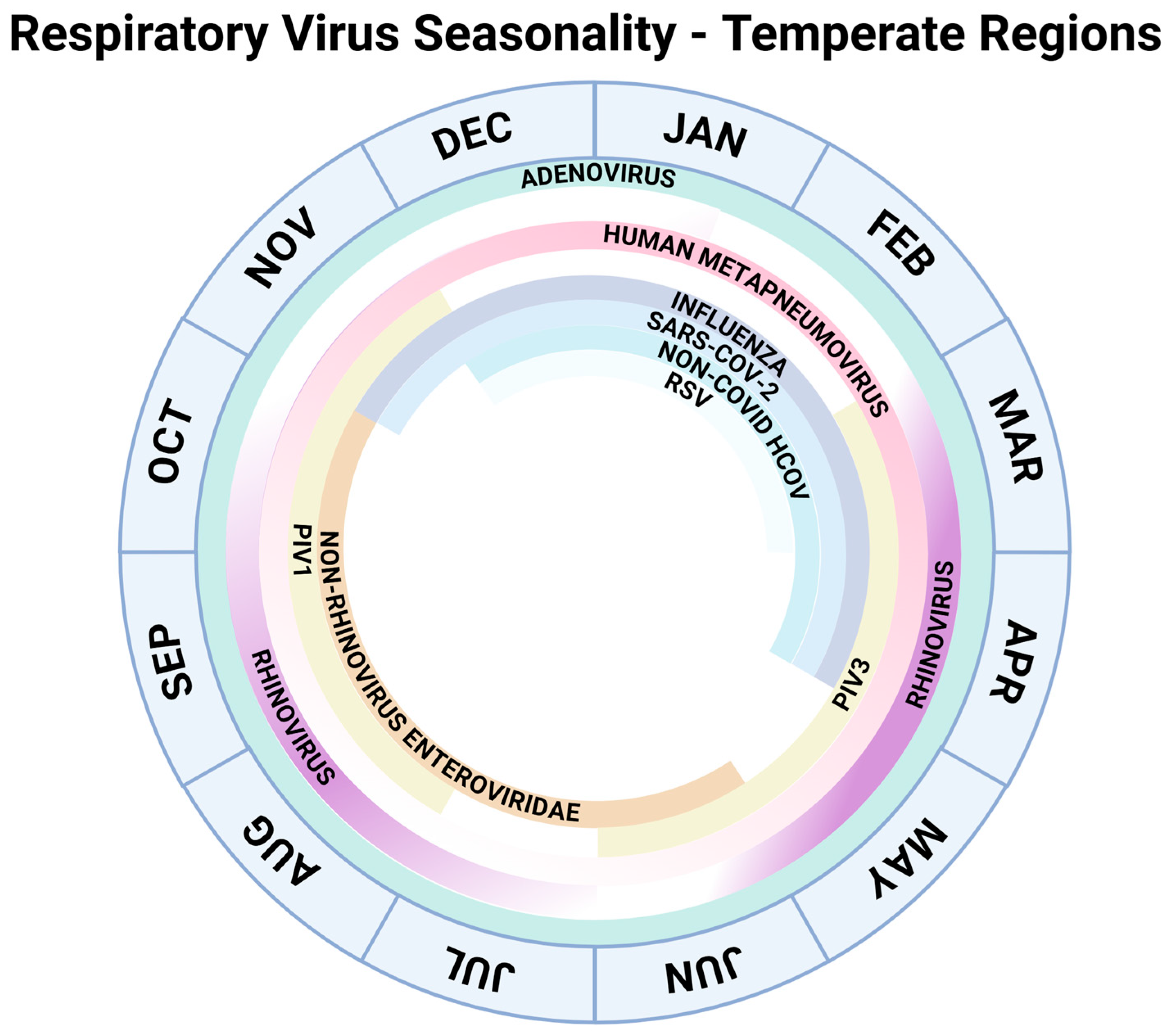

- Giuliani, A. Created in BioRender. 2025. Available online: https://BioRender.com/cu1xygq (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Kumar, D.; Ferreira, V.H.; Blumberg, E.; Silveira, F.; Cordero, E.; Perez-Romero, P.; Aydillo, T.; Danziger-Isakov, L.; Limaye, A.P.; Carratala, J.; et al. A 5-Year Prospective Multicenter Evaluation of Influenza Infection in Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2018, 67, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. Influenza Vaccine Composition for the 2025–2026 U.S. Influenza Season; Federal Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2025.

- Faccin, F.C.; Perez, D.R. Pandemic preparedness through vaccine development for avian influenza viruses. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2347019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger-Isakov, L.; Kumar, D.; AST ID Community of Practice. Vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients: Guidelines from the American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Pinto, A.; Abreu, I.; Martins, A.; Bastos, J.; Araújo, J.; Pinto, R. Vaccination After Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: A Review of the Literature and Proposed Vaccination Protocol. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, P.P.; Handler, L.; Weber, D.J. A Systematic Review of Safety and Immunogenicity of Influenza Vaccination Strategies in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2018, 66, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, E.; Roca-Oporto, C.; Bulnes-Ramos, A.; Aydillo, T.; Gavaldà, J.; Moreno, A.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Montejo, J.M.; Fortun, J.; Muñoz, P.; et al. Two Doses of Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Improve Immune Response in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: Results of TRANSGRIPE 1–2, a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2017, 64, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombelli, M.; Neofytos, D.; Huynh-Do, U.; Sánchez-Céspedes, J.; Stampf, S.; Golshayan, D.; Dahdal, S.; Stirnimann, G.; Schnyder, A.; Garzoni, C.; et al. Immunogenicity of High-Dose Versus MF59-Adjuvanted Versus Standard Influenza Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: The Swiss/Spanish Trial in Solid Organ Transplantation on Prevention of Influenza (STOP-FLU Trial). Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2024, 78, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscona, A. Neuraminidase Inhibitors for Influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T.M.; Bernstein, H.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Englund, J.A.; File, T.M.; Fry, A.M.; Gravenstein, S.; Hayden, F.G.; Harper, S.A.; Hirshon, J.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2019, 68, e1–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitha, E.; Krivan, G.; Jacobs, F.; Nagler, A.; Alrabaa, S.; Mykietiuk, A.; Kenwright, A.; Le Pogam, S.; Clinch, B.; Vareikiene, L. Safety, Resistance, and Efficacy Results from a Phase IIIb Study of Conventional- and Double-Dose Oseltamivir Regimens for Treatment of Influenza in Immunocompromised Patients. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2019, 8, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee On Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children 2022–2023. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022059275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, M.G.; Portsmouth, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Shishido, T.; Mitchener, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Uehara, T.; Hayden, F.G. Early treatment with baloxavir marboxil in high-risk adolescent and adult outpatients with uncomplicated influenza (CAPSTONE-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer, M.; Malinis, M.; McManus, D.; Davis, M.; Shah, S.; Trubin, P.; Topal, J.E.; Azar, M.M. Clinical outcomes of baloxavir versus oseltamivir in immunocompromised patients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant. Soc. 2024, 26, e14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, F.G.; Sugaya, N.; Hirotsu, N.; Lee, N.; de Jong, M.D.; Hurt, A.C.; Ishida, T.; Sekino, H.; Yamada, K.; Portsmouth, S.; et al. Baloxavir Marboxil for Uncomplicated Influenza in Adults and Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cidara Therapeutics Announces Positive Topline Results from Its Phase 2b Navigate Trial Evaluating CD388, a Non-Vaccine Preventative of Seasonal Influenza (2025). Cidara Therepeutics. Available online: https://www.cidara.com/news/cidara-therapeutics-announces-positive-topline-results-from-its-phase-2b-navigate-trial-evaluating-cd388-a-non-vaccine-preventative-of-seasonal-influenza/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Foroutan, F.; Rayner, D.; Oss, S.; Straccia, M.; de Vries, R.; Raju, S.; Ahmed, F.; Kingdon, J.; Bhagra, S.; Tarani, S.; et al. Clinical Practice Recommendations on the Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies on Outcomes in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin. Transplant. 2025, 39, e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, F.; Papanicolau, G.; Dadwal, S.; Pergam, S.A.; Wingard, J.R.; Boghdadly, Z.E.; Abidi, M.Z.; Waghmare, A.; Shahid, Z.; Michaels, L.; et al. Frequently Asked Questions on Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Recipients From the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and the American Society of Hematology. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmo, A.; Gardiner, D.; Ushiro-Lumb, I.; Ravanan, R.; Forsythe, J.L.R. The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Solid Organ Transplantation: Two Years Into a Pandemic. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.A.; Motoa, G.; Raja, M.A.; Frattaroli, P.; Fernandez, A.; Anjan, S.; Courel, S.C.; Natori, A.; O’Brien, C.B.; Phancao, A.; et al. Difference between SARS-CoV-2, seasonal coronavirus, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant. Soc. 2023, 25, e13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera, J.T.; Árbol, B.G.; Mittal, A.; Hall, V.; Marinelli, T.; Bahinskaya, I.; Selzner, N.; McDonald, M.; Schiff, J.; Sidhu, A.; et al. Longitudinal outcomes of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients from 2020 to 2023. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2024, 24, 1303–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.C.; Webber, A.; Lauring, A.S.; Bendall, E.; Papalambros, L.K.; Safdar, B.; Ginde, A.A.; Peltan, I.D.; Brown, S.M.; Gaglani, M.; et al. Effectiveness of 2024–2025 COVID-19 Vaccination Against COVID-19 Hospitalization and Severe In-Hospital Outcomes—IVY Network 2025, 26 Hospitals, September 1, 2024-April 30, 2025. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Health Sci. 2025, 33, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshukairi, A.N.; Al-Qahtani, A.A.; Obeid, D.A.; Dada, A.; Almaghrabi, R.S.; Al-Abdulkareem, M.A.; Alahideb, B.M.; Alsanea, M.S.; Alsuwairi, F.A.; Alhamlan, F.S. Molecular Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and Clinical Manifestations among Organ Transplant Recipients with COVID-19. Viruses 2023, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.L.; Azzi, J.R.; Eghtesad, B.; Priddy, F.; Stolman, D.; Siangphoe, U.; Leony Lasso, I.; de Windt, E.; Girard, B.; Zhou, H.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the mRNA-1273 Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e591–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, M.M.L.; Messchendorp, A.L.; Frölke, S.C.; Imhof, C.; Koomen, V.J.; Malahe, S.R.K.; Vart, P.; Geers, D.; de Vries, R.D.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; et al. Alternative strategies to increase the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in kidney transplant recipients not responding to two or three doses of an mRNA vaccine (RECOVAC): A randomised clinical trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafea, M.T.; Haidar, G. COVID-19 Prevention in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: Current State of the Evidence. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 37, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl-Schwaighofer, R.; Heinzel, A.; Mayrdorfer, M.; Jabbour, R.; Hofbauer, T.M.; Merrelaar, A.; Eder, M.; Regele, F.; Doberer, K.; Spechtl, P.; et al. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Response 4 Weeks After Homologous vs Heterologous Third Vaccine Dose in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanodja, B.; Ronicke, S.; Budde, K.; Jens, A.; Hammett, C.; Koch, N.; Seelow, E.; Waiser, J.; Zukunft, B.; Bachmann, F.; et al. Serological Response to Three, Four and Five Doses of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaba, A.H.; Johnston, T.S.; Aytenfisu, T.Y.; Akinde, O.; Eby, Y.; Ruff, J.E.; Abedon, A.T.; Alejo, J.L.; Blankson, J.N.; Cox, A.L.; et al. A Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine Does Not Induce Neutralization of the Omicron Variant Among Solid Organ Transplant Recipients with Suboptimal Vaccine Response. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, S.R.; Loft, J.A.; Pérez-Alós, L.; Heftdal, L.D.; Hansen, C.B.; Møller, D.L.; Pries-Heje, M.M.; Hasselbalch, R.B.; Fogh, K.; Hald, A.; et al. The Impact of Time between Booster Doses on Humoral Immune Response in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients Vaccinated with BNT162b2 Vaccines. Viruses 2024, 16, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manothummetha, K.; Chuleerarux, N.; Sanguankeo, A.; Kates, O.S.; Hirankarn, N.; Thongkam, A.; Dioverti-Prono, M.V.; Torvorapanit, P.; Langsiri, N.; Worasilchai, N.; et al. Immunogenicity and Risk Factors Associated with Poor Humoral Immune Response of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Recipients of Solid Organ Transplant: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e226822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Morishita, T.; Suzumura, K.; Hanatate, F.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sasaki, N.; Lee, S.; Fujita, K.; Hara, T.; Araki, H.; et al. The Trajectory of the COVID-19 Vaccine Antibody Titers Over Time and the Association of Mycophenolate Mofetil in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, S.E.; Berger, S.P.; van Leer-Buter, C.C.; Kroesen, B.; van Baarle, D.; Sanders, J.F.; OPTIMIZE study group. Enhanced Humoral Immune Response After COVID-19 Vaccination in Elderly Kidney Transplant Recipients on Everolimus Versus Mycophenolate Mofetil-containing Immunosuppressive Regimens. Transplantation 2022, 106, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messchendorp, A.L.; Zaeck, L.M.; Bouwmans, P.; van den Broek, D.A.J.; Frölke, S.C.; Geers, D.; Imhof, C.; Malahe, S.R.K.; Schmitz, K.S.; Reinders, J.; et al. Replacing Mycophenolate Mofetil by Everolimus in Kidney Transplant Recipients to Increase Vaccine Immunogenicity: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2025, ciaf107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.H.; Keith, B.; Mavandadnejad, F.; Ferro, A.; Marocco, S.; Amidpour, G.; Kurtesi, A.; Qi, F.; Gingras, A.; Hall, V.G.; et al. Longitudinal Innate and Heterologous Adaptive Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 in Transplant Recipients with Prior Omicron Infection: Limited Neutralization but Robust CD4+ T-Cell Activity. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant. Soc. 2025, 27, e70067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiol, N.; Aso, O.; Gómez-Pérez, L.; Triquell, M.; Roch, N.; Lázaro, E.; Esquirol, A.; González, I.; López-Contreras, J.; Sierra, J.; et al. mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine safety and COVID-19 risk perception in recently transplanted allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9687–9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimraj, A.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Kim, A.Y.; Li, J.Z.; Baden, L.R.; Johnson, S.; Shafer, R.W.; Shoham, S.; Tebas, P.; Bedimo, R.; et al. 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America on the Management of COVID-19: Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Pemivibart for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2024, ciae435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INVIVYD. PEMGARDA Authorized for Emergency Use. Available online: https://pemgarda.com/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=21506626247 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Mozaffari, E.; Chandak, A.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Chima-Melton, C.; Berry, M.; Amin, A.N.; Sax, P.E.; Kalil, A.C. Remdesivir-Associated Survival Outcomes Among Immunocompromised Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: Real-world Evidence from the Omicron-Dominant Era. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2024, 79, S149–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera, J.T.; Árbol, B.G.; Bahinskaya, I.; Marks, N.; Humar, A.; Kumar, D. Short-course early outpatient remdesivir prevents severe disease due to COVID-19 in organ transplant recipients during the omicron BA.2 wave. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2023, 23, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, F.; Budde, K.; Van Gelder, T.; Bergan, S.; Lawson, R.; Noceti, O.; Venkataramanan, R.; Elens, L.; Moes, D.J.A.R.; Hesselink, D.A.; et al. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Dosage Adjustments of Immunosuppressive Drugs When Combined with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir in Patients with COVID-19. Ther. Drug Monit. 2023, 45, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, E.; Paredes, R.; Gardner, A.; Almas, M.; Baniecki, M.L.; Guan, S.; Tudone, E.; Antonucci, S.; Gregg, K.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; et al. Extended nirmatrelvir-ritonavir treatment durations for immunocompromised patients with COVID-19 (EPIC-IC): A placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, C.; Palacios, C.F.; Azar, M.M.; Cohen, E.; Malinis, M. Real-world experience with available, outpatient COVID-19 therapies in solid organ transplant recipients during the omicron surge. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2022, 22, 2458–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testaert, H.; Bouet, M.; Valour, F.; Gigandon, A.; Lafon, M.; Philit, F.; Sénéchal, A.; Casalegno, J.; Blanchard, E.; Le Pavec, J.; et al. Incidence, management and outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in adult lung transplant recipients: A 9-year retrospective multicentre study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, L.D.; Gaur, S.; Bellanti, J.A. The third pandemic: The respiratory syncytial virus landscape and specific considerations for the allergist/immunologist. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2023, 44, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, N.I.; Terstappen, J.; Baral, R.; Bardají, A.; Beutels, P.; Buchholz, U.J.; Cohen, C.; Crowe, J.E.; Cutland, C.L.; Eckert, L.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: The vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e2–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassopoulou, C.; Medić, S.; Ferous, S.; Boufidou, F.; Tsakris, A. Development, Current Status, and Remaining Challenges for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MRESVIA—Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine Suspension (2025). DailyMed: Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=e5c837e7-41e8-496a-9c85-6b0453b35948 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Trubin, P.; Azar, M.M.; Kotton, C.N. The respiratory syncytial virus vaccines are here: Implications for solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2024, 24, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.C.; Parameswaran, L.; DeHaan, E.N.; Wyper, H.; Rahman, F.; Jiang, Q.; Li, W.; Patton, M.; Lino, M.M.; Majid-Mahomed, Z.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of the Bivalent Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Subunit Vaccine in Immunocompromised or Renally Impaired Adults. Vaccines 2025, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, S.E.; Terebuh, P.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R.; Davis, P.B. Effectiveness and Safety of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine for US Adults Aged 60 Years or Older. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e258322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redjoul, R.; Robin, C.; Softic, L.; Ourghanlian, C.; Cabanne, L.; Beckerich, F.; Caillault, A.; Soulier, A.; Daumerie, P.; Fourati, S.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2533828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlin, J.; Skotnicova, A.; Dvorackova, E.; Palavandishvili, N.; Smetanova, J.; Svorcova, M.; Vaculova, M.; Hubacek, P.; Fila, L.; Trojanek, M.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F3 vaccine in lung transplant recipients elicits CD4+ T cell response in all vaccinees. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2025, 25, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, V.G.; Alexander, A.A.; Mavandadnejad, F.; Kern-Smith, M.; Dang, X.; Kang, R.; Humar, S.; Winichakoon, P.; Johnstone, R.; Aversa, M.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of adjuvanted respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in high-risk transplant recipients: An Interventional Cohort Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025; ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2025.09.013. [Google Scholar]

- de Fontbrune, F.S.; Robin, M.; Porcher, R.; Scieux, C.; de Latour, R.P.; Ferry, C.; Rocha, V.; Boudjedir, K.; Devergie, A.; Bergeron, A.; et al. Palivizumab treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2007, 45, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permpalung, N.; Mahoney, M.V.; McCoy, C.; Atsawarungruangkit, A.; Gold, H.S.; Levine, J.D.; Wong, M.T.; LaSalvia, M.T.; Alonso, C.D. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes among respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-infected hematologic malignancy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients receiving palivizumab. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, D. RSV Prevention Therapy Palivizumab to Be Discontinued. MPR: Medical Professionals Reference. 13 August 2025. Available online: https://www.empr.com/news/rsv-prevention-therapy-palivizumab-to-be-discontinued/#xd_co_f=MjU4NDVkMTItODAzZi00OWUzLTljZjUtNmQyMTNiNTdmMjc4~" (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- De Zwart, A.; Riezebos-Brilman, A.; Lunter, G.; Vonk, J.; Glanville, A.R.; Gottlieb, J.; Permpalung, N.; Kerstjens, H.; Alffenaar, J.; Verschuuren, E. Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Human Metapneumovirus, and Parainfluenza Virus Infections in Lung Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review of Outcomes and Treatment Strategies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 2252–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.W.; Kiser, T.H.; Morrisette, T.; Zamora, M.R.; Lyu, D.M.; Kiser, J.L. Ribavirin and cellular ribavirin-triphosphate concentrations in blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in two lung transplant patients with respiratory syncytial virus. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021, 23, e13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permpalung, N.; Thaniyavarn, T.; Saullo, J.L.; Arif, S.; Miller, R.A.; Reynolds, J.M.; Alexander, B.D. Oral and Inhaled Ribavirin Treatment for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Lung Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2020, 104, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.K. Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.H.; Mann, A.J.; Maas, B.M.; Zhao, T.; Bevan, M.; Schaeffer, A.K.; Liao, L.E.; Catchpole, A.P.; Hilbert, D.W.; Aubrey Stoch, S.; et al. A Phase 2a, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Human Challenge Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Molnupiravir in Healthy Participants Inoculated with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Pulm. Ther. 2025, 11, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-oi/guidelines-adult-adolescent-oi.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Erard, V.; Guthrie, K.A.; Seo, S.; Smith, J.; Huang, M.; Chien, J.; Flowers, M.E.D. Reduced Mortality of Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Due to Antiviral Therapy and Changes in Transplantation Practices. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2015, 61, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, G.; Boeckh, M.; Singh, N. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Solid Organ and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: State of the Evidence. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.G.; Kotton, C.N. What’s New: Updates on Cytomegalovirus in Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation 2024, 108, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, P.; de la Camara, R.; Robin, C.; Crocchiolo, R.; Einsele, H.; Hill, J.A.; Hubacek, P.; Navarro, D.; Cordonnier, C.; Ward, K.N.; et al. Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stem cell transplantation from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e260–e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardinger, K.L.; Brennan, D.C. Cytomegalovirus Treatment in Solid Organ Transplantation: An Update on Current Approaches. Ann. Pharmacother. 2024, 58, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldman, M.R.; Boeckh, M.J.; Limaye, A. Current and Future Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of Cytomegalovirus Infections in Transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2025, 81, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stobart, C.C.; Nosek, J.M.; Moore, M.L. Rhinovirus Biology, Antigenic Diversity, and Advancements in the Design of a Human Rhinovirus Vaccine. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamun, T.I.; Ali, A.; Hosen, N.; Rahman, J.; Islam, A.; Akib, G.; Zaman, K.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, F.M.A.; Ibenmoussa, S.; et al. Designing a multi-epitope vaccine candidate against human rhinovirus C utilizing immunoinformatics approach. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1364129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Frøysa, I.T.; Lysvand, H.; Calitz, C.; Smura, T.; Schjelderup Nilsen, H.; Høyer, E.; Afset, J.E.; Sridhar, A.; Wolthers, K.C.; et al. The combination of pleconaril, rupintrivir, and remdesivir efficiently inhibits enterovirus infections in vitro, delaying the development of drug-resistant virus variants. Antivir. Res. 2024, 224, 105842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnyder Ghamloush, S.; Essink, B.; Hu, B.; Kalidindi, S.; Morsy, L.; Egwuenu-Dumbuya, C.; Kapoor, A.; Girard, B.; Dhar, R.; Lackey, R.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an mRNA-Based hMPV/PIV3 Combination Vaccine in Seropositive Children. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principi, N.; Fainardi, V.; Esposito, S. Human Metapneumovirus: A Narrative Review on Emerging Strategies for Prevention and Treatment. Viruses 2025, 17, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschner, R.A.; Russell, K.L.; Abuja, M.; Bauer, K.M.; Faix, D.J.; Hait, H.; Henrick, J.; Jacobs, M.; Liss, A.; Lynch, J.A.; et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of the live, oral adenovirus type 4 and type 7 vaccine, in U.S. military recruits. Vaccine 2013, 31, 2963–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsana, N.; Ha, D.; Ho, D.Y. Treating Adenovirus Infection in Transplant Populations: Therapeutic Options Beyond Cidofovir? Viruses 2025, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Fauci, A.S. Rethinking next-generation vaccines for coronaviruses, influenzaviruses, and other respiratory viruses. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.M.; Sourimant, J.; Toots, M.; Yoon, J.; Ikegame, S.; Govindarajan, M.; Watkinson, R.E.; Thibault, P.; Makhsous, N.; Lin, M.J.; et al. Orally efficacious broad-spectrum allosteric inhibitor of paramyxovirus polymerase. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaly, R.F.; Marty, F.M.; Wolfe, C.R.; Lawrence, S.J.; Dadwal, S.; Soave, R.; Farthin, J.; Hawley, S.; Montanez, P.; Hwang, J.; et al. DAS181 Treatment of Severe Lower Respiratory Tract Parainfluenza Virus Infection in Immunocompromised Patients: A Phase 2 Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, e773–e781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaly, R.F.; Shah, D.; Boeckh, M.J. Management of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2014, 59, S344–S351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezavi, M.; Sloan, A.; Singh, R.S.P.; Chen, L.F.; Kim, J.H.; Shojaee, N.; Toussi, S.S.; Prybylski, J.; Baniecki, M.L.; Bergman, A.; et al. Virologic Response and Safety of Ibuzatrelvir, A Novel SARS-CoV-2 Antiviral, in Adults with COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2025, 80, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, C.; Yasuda, H.; Hiki, M.; Shirane, S.; Yamana, T.; Uchimara, A.; Inano, T.; Takaku, T.; Hamano, Y.; Ando, M. Case report: Ensitrelvir for treatment of persistent COVID-19 in lymphoma patients: A report of two cases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1287300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babusis, D.; Kim, C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Geng, G.; Ip, C.; Kozon, N.; Le, H.; Leung, J.; Pitts, J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Broad-Spectrum Antivirals Remdesivir and Obeldesivir with a Consideration to Metabolite GS-441524: Same, Similar, or Different? Viruses 2025, 17, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horga, A.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Kowalczyk, J.J.; Pietropaolo, K.; Belanger, B.; Lin, K.; Perkins, K.; Hammond, J. Phase II study of bemnifosbuvir in high-risk participants in a hospital setting with moderate COVID-19. Future Virol. 2023, 18, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart, G.; Bobardt, M.; Bentzen, B.H.; Yan, Y.; Thomson, A.; Klumpp, K.; Becker, S.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Miller, M.; Gallay, P. Post-infection treatment with the E protein inhibitor BIT225 reduces disease severity and increases survival of K18-hACE2 transgenic mice infected with a lethal dose of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Eze, K.; Noulin, N.; Horvathova, V.; Murray, B.; Baillet, M.; Grey, L.; Mori, J.; Adda, N. EDP-938, a Respiratory Syncytial Virus Inhibitor, in a Human Virus Challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, R.E.; DeVincenzo, J.; Conery, A.L.; Ahmad, A.; Or, Y.S.; Rhodin, M.H.J. EDP-938 Has a High Barrier to Resistance in Healthy Adults Experimentally Infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, e290–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevendal, A.T.K.; Hurley, S.; Bartlett, A.W.; Rawlinson, W.; Walker, G.J. Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Safety of RSV-Specific Monoclonal Antibodies and Antivirals in Development. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Koval, C.; DeVincenzo, J.P.; Walsh, E.E. Compassionate use experience with high-titer respiratory syncytical virus (RSV) immunoglobulin in RSV-infected immunocompromised persons. Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant. Soc. 2017, 19, e12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, A.; Hajifathali, A.; Mohammadian, M.; Sankanian, G.; Sayahinouri, M.; Dehghani Ghorbi, M.; Roshandel, E.; Aghdami, N. Virus-Specific T Cells: Promising Adoptive T Cell Therapy Against Infectious Diseases Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 13, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Agent | Class/Mechanism | Dosing & Schedule | Timing | Clinical/Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluzone High-Dose | HD-IIV3 (inactivated) | 60 µg hemagglutinin/0.5 mL | Annual; pre-Tx 1 preferred [15]; ≥1 month post-SOT [11], ≥3–6 month post-HCT [12] | ↑ Seroconversion vs. standard; ↓ pneumonia, ICU, mortality [8] | Safe; mild AEs 2 |

| Fluad | aIIV3 (adjuvanted) | 15 µg hemagglutinin/0.5 mL | Same as above | MF59 adjuvant enhances immune response [15] | Well-tolerated |

| Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) | Neuraminidase inhibitor | 75 mg PO daily ×12 weeks (pre-exp) or ×7 days (post-exp) [3] | Pre-exposure if vaccine suboptimal [3]; post-exposure as treatment | ↓ Influenza complications; improved outcomes if given within 48 h [8] | Safe; renally adjust |

| Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) | Cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor | Single PO dose, consider in combo with NAI [19] | Early outpatient (<48 h) [19] | Comparable efficacy to oseltamivir; ↑ resistance risk [22] | Limited data in SOT |

| CD388 | Investigational neuraminidase inhibitor conjugate | Single injection (24 week efficacy) [23] | Seasonal pre-exposure | 76% efficacy in healthy adults; non-vaccine option [23] | Phase 2b; well tolerated [23] |

| Agent | Class/Mechanism | Dosing & Schedule | Timing | Clinical/Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA-1273 (Spikevax) | mRNA vaccine | 4-dose (0, 4 weeks, +4 weeks, 6 month booster) | Pre-Tx 1 preferred but should also repeat post-Tx 1; ≥1 month post-SOT [28], ≥3 months post-HCT [24] | 20–40% seroconversion after 2 doses; improved ≥3 [31,33] | No rejection/GVHD 2 [31,43] |

| mRNA BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) | mRNA vaccine | 4-dose (0, 3 weeks, +4 weeks, 6 month booster) | Same as above | Boosters improve humoral response [38] | Safe in SOT/HCT [24] |

| Pemivibart (Pemgarda) | Long-acting mAb | 4500 mg IV q 3 months | Pre-Tx 1 preferred | ↓ Hospitalization; variant-dependent [44] | EUA 3, limited data |

| Remdesivir (Veklury) | RNA-polymerase inhibitor | 3–5 days IV | Early (<7 days) outpatient or inpatient [47] | ↓ Hospitalization/mortality [46,47] | Safe; monitor renal function |

| Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir (Paxlovid) | Protease inhibitor combination | 5–15 days PO | Early (<5 days) [49] | ↓ Viral load; monitor DDIs 4 | CYP3A interaction risk [48] |

| Molnupiravir (Lagevrio) | Nucleoside analog | 5 days PO | Early (<5 days) [50] | ↓ Hospitalization; less effective than remdesivir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir [50] | Well-tolerated |

| Agent | Class/Mechanism | Dosing | Timing | Clinical/Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrysvo | Protein subunit (non-adjuvanted) vaccine | Single pre-season dose [54] | Pre-Tx 1 preferred; ≥3–6 months post-Tx 1 [12,61] | 50–69% VE 2; 1-year antibody persistence; Lower response in HCT (29–44%) [58,59] | Rare GBS 3; no rejection [58,61] |

| Arexvy | Protein subunit (adjuvanted) vaccine | Same as above | Same as above | 50–69% VE 2; improved CD4+ response; preferred for immunocompromised [61] | Rare GBS 3; mild AEs 4 [58] |

| mRESVIA | mRNA vaccine | Same as above, not preferred | Same as above, not preferred | Potential in high-risk SOT [56] | Safe in PLWH 5; awaiting SOT data [70] |

| Nirsevimab | Long-acting mAb (F-protein) | Single IM pre-season, adult dose unknown | No adult data | 70% efficacy in infants; no adult data; potential SOT use [53] | Safe in infants |

| Virus | Agent | Mechanism | Stage | Findings | Status in Transplant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Ibuzatrelvir | Protease inhibitor | Phase 2 | ↓ Viral load [88] | No data |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Ensitrelvir | Protease inhibitor | Phase 3 | ↓ Symptoms [89] | Potential benefit in IC 1 [89] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Obeldesivir | RNA pol inhibitor | Phase 3 | ↓ Symptoms [90] | No data |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Bemnifosbuvir | RNA pol inhibitor | Phase 2 | ↓ Viral load [91] | No data |

| SARS-CoV-2 | BIT225 | Envelope protein inhibitor | Phase 2 | Did not meet primary efficacy endpoint [92] | Investigational |

| RSV | Ribavirin | Nucleoside analog (inhaled preferred) | Approved | ↓ LRTI progression ± IVIG/mAb, ?effect in lung Tx 2 [3,66] | Standard care |

| RSV | Molnupiravir | Nucleoside analog | Approved | ↓ Symptoms [69] | No data |

| RSV | EDP-938 | Nucleoprotein inhibitor | Phase 2 | ↓ Viral load/symptoms [93,94] | No data |

| RSV | ALN-RSV01 | siRNA (inhaled) | Phase 2 | ↓ BOS 3 in lung Tx 2; safe [95] | Promising adjunct |

| RSV | RI-001 and RI-002 | RSV Ab-rich IVIG | Approved | Early use may improve outcomes in IC [96] | Potential benefit in HCT, no SOT data [96] |

| Other RVI | DAS-181 | Sialidase fusion protein (inhaled) | Phase 2 | Benefit in select immunocompromised [86] | Investigational |

| Other RVI | T-cell adoptive therapy | Seropositive donor T cells | Phase 1–2 | ↓ Viral load, improve survival [97] | Investigational, promising in HCT |

| Virus | Pre-Exposure | PrEP 1 Timing | Post-Exposure | PEP 2 Timing | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza | Annual IIV; oseltamivir ×12 weeks | Annual vaccine: ≥1 months post-SOT, ≥3–6 months post-HCT | Oseltamivir ×7 days | Best within 48 h | Vaccine cornerstone; antiviral bridge |

| SARS-CoV-2 | mRNA booster vaccines; Pemivibart q 3 months | Boosters plus annual vaccine, timing same as above | Remdesivir, nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, molnupiravir | Early within 7 days | Variant-dependent prophylaxis |

| RSV | Single vaccine; mAb | Annual pre-season | Ribavirin ± IVIG/mAb | Early | Adjuvanted vaccines enhance immunity |

| Other RVI | Trial vaccines (hMPV, PIV) | Vaccine-specific | Cidofovir, ribavirin | Case-specific | Encourage trial enrollment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Giuliani, A.A.M.; Chen, V.; Law, N. Respiratory Viral Infection Prophylaxis and Treatment in the Transplant Population. Viruses 2026, 18, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010008

Giuliani AAM, Chen V, Law N. Respiratory Viral Infection Prophylaxis and Treatment in the Transplant Population. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuliani, Adriana A. M., Victor Chen, and Nancy Law. 2026. "Respiratory Viral Infection Prophylaxis and Treatment in the Transplant Population" Viruses 18, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010008

APA StyleGiuliani, A. A. M., Chen, V., & Law, N. (2026). Respiratory Viral Infection Prophylaxis and Treatment in the Transplant Population. Viruses, 18(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010008