Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing Method Reveals Endemic Circulation of Human Adenovirus Type 3 in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Extraction

2.2. Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing and Base-Calling

2.3. Genome Assembly, Quality Control, and Type Classification

2.4. Phylogenetic and Molecular Clock Analyses

2.5. Sliding Window Analysis and Nucleotide Composition Analysis

2.6. In Silico Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Profiles

2.7. Ethical Statement

3. Results

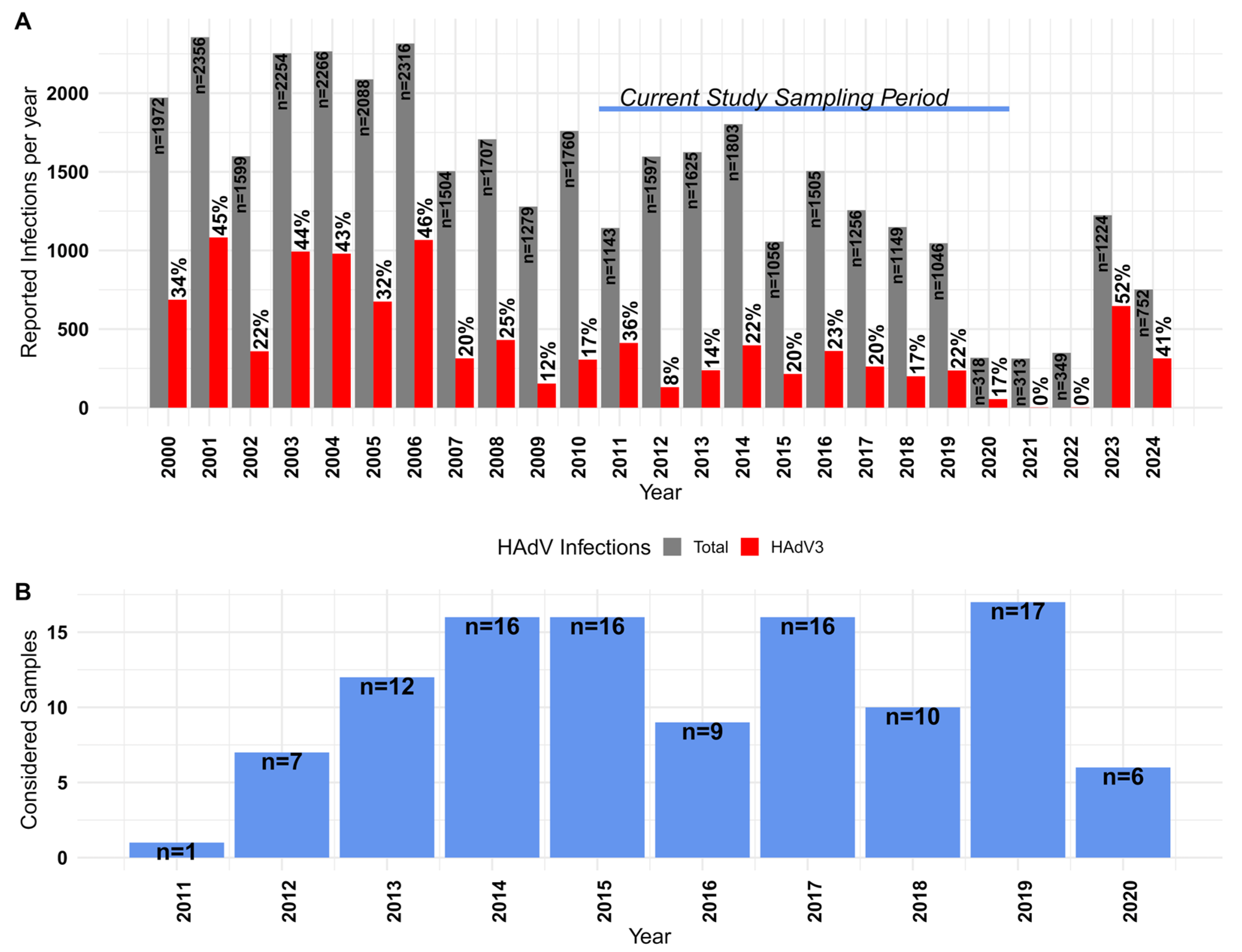

3.1. Epidemiological Context of HAdV-3 in Japan

3.2. HAdV-3 Tiled Amplicon Approach for Whole-Genome Sequencing

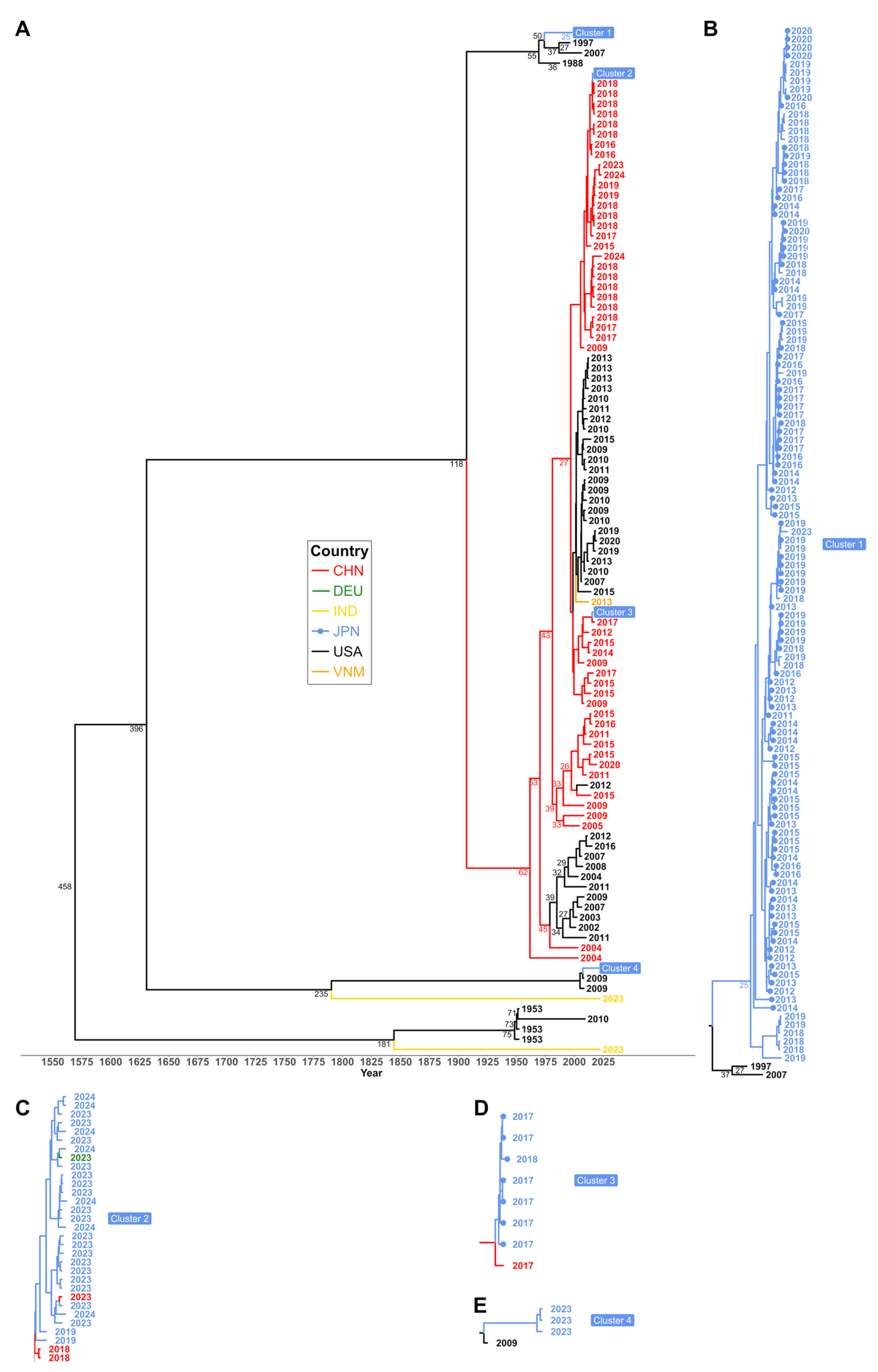

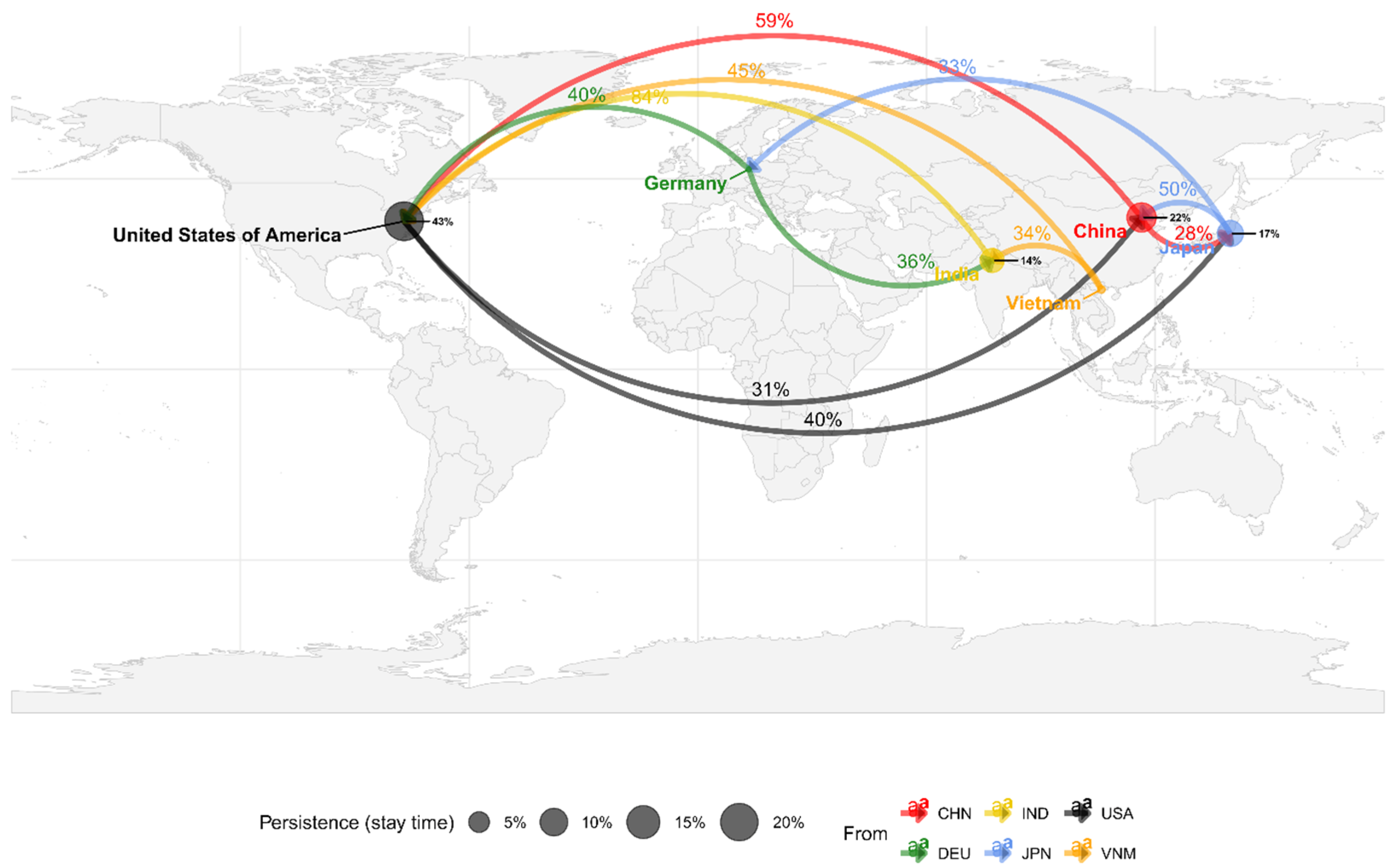

3.3. Inferred Bayesian Phylogenetic Relation of HAdV-3 Sequences

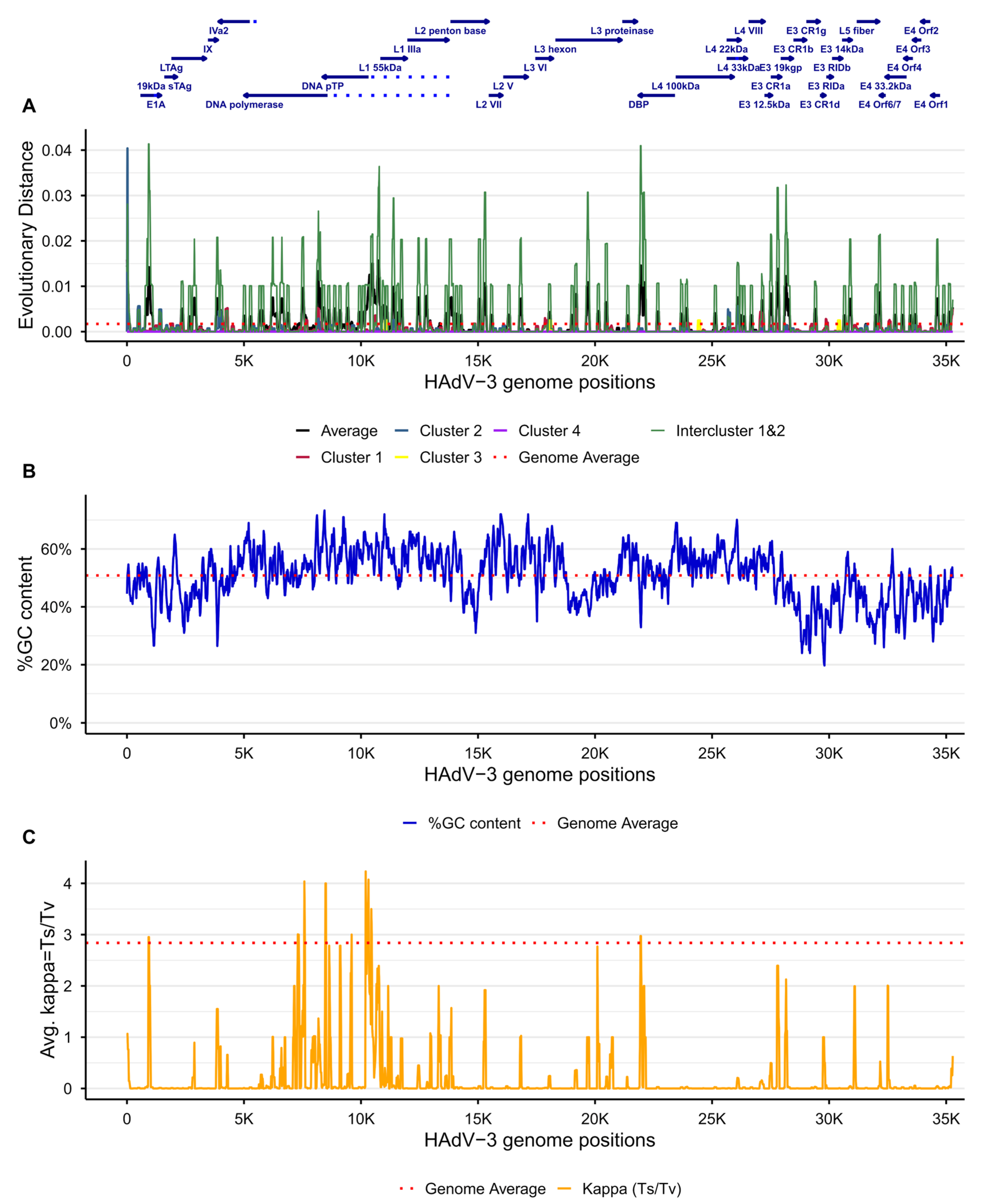

3.4. Uneven %GC Content Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HAdV-3 | Human adenovirus type 3 |

| HAdV-B | Mastadenovirus blackbeardi |

| HAdV-C | Mastadenovirus caesari |

| NIID | National Institute of Infectious Diseases |

| pTP | Pre-terminal protein |

| DBP | DNA-binding protein |

| RFLP | Restriction fragment length polymorphisms |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| ML | Maximum-likelihood |

| IASR | Infectious Agents Surveillance Report |

| HPD | High-posterior distribution |

| tMRCA | Time to the most recent common ancestor |

| CHN | China |

| DEU | Germany |

| IND | India |

| JPN | Japan |

| USA | United States of America |

| VNM | Vietnam |

References

- ICTV. Genus: Mastadenovirus. 2025. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/chapter/adenoviridae/adenoviridae/mastadenovirus (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Kajon, A.E. Adenovirus infections: New insights for the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0083622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giardina, F.A.M.; Pellegrinelli, L.; Novazzi, F.; Vian, E.; Biscaro, V.; Russo, C.; Ranno, S.; Pagani, E.; Masi, E.; Tiberio, C.; et al. Epidemiological impact of human adenovirus as causative agent of respiratory infections: An Italian multicentre retrospective study, 2022–2023. J. Infect. Chemother. 2024, 30, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, E.J.J. What is the risk of a deadly adenovirus pandemic? PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashizume, M.; Aoki, K.; Ohno, S.; Kitaichi, N.; Yawata, N.; Gonzalez, G.; Nonaka, H.; Sato, S.; Takaoka, A. Disinfectant potential in inactivation of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis-related adenoviruses by potassium peroxymonosulfate. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIID. National Institute of Infectious Diseases—Infectious Agent Surveillance Report. Available online: https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/en/iasr.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Nemerow, G.R.; Stewart, P.L.; Reddy, V.S. Structure of human adenovirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, F.; Greber, U.F. The Adenovirus Death Protein—A small membrane protein controls cell lysis and disease. Febs. Lett. 2020, 594, 1861–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.A.; Bouvier, M. Immune evasion by adenoviruses: A window into host-virus adaptation. Febs. Lett. 2019, 593, 3496–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.; Koyanagi, K.O.; Aoki, K.; Kitaichi, N.; Ohno, S.; Kaneko, H.; Ishida, S.; Watanabe, H. Intertypic modular exchanges of genomic segments by homologous recombination at universally conserved segments in human adenovirus species D. Gene 2014, 547, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, H.; Sera, N.; Gonzalez, G.; Hanaoka, N.; Fujimoto, T. First isolation of a new type of human adenovirus (genotype 79), species Human mastadenovirus B (B2) from sewage water in Japan. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.K. Genomic diversity of human adenovirus type 3 isolated in Fukui, Japan over a 24-year period. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 66, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, E.; Broberg, E.K.; Connor, T.; Hodcroft, E.B.; Komissarov, A.B.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Melidou, A.; Neher, R.A.; O’Toole, A.; Pereyaslov, D.; et al. Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Gonzalez, G.; Kobayashi, M.; Hanaoka, N.; Carr, M.J.; Konagaya, M.; Nojiri, N.; Ogi, M.; Fujimoto, T. Pediatric Infections by Types 2, 89, and a Recombinant Type Detected in Japan between 2011 and 2018. Viruses 2019, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M.; Ogawa, T.; Kubonoya, H.; Yoshizumi, H.; Shinozaki, K. Detection and sequence-based typing of human adenoviruses using sensitive universal primer sets for the hexon gene. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, N.E.; Vlkova, M.; Faisal, M.B.; Silander, O.K. Rapid and inexpensive whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 using 1200 bp tiled amplicons and Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2020, 5, bpaa014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.; Carr, M.; Kelleher, T.M.; O’Byrne, E.; Banka, W.; Keogan, B.; Bennett, C.; Franzoni, G.; Keane, P.; Kenna, C.; et al. Multiple introductions of monkeypox virus to Ireland during the international mpox outbreak, May 2022 to October 2023. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2300505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 4572–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemey, P.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Suchard, M.A. Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Infectious Diseases. Infectious Disease Surveillance System in Japan. 2018. Available online: https://id-info.jihs.go.jp/surveillance/idss/nesid-program-summary/nesid_en.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Duffy, S.; Shackelton, L.A.; Holmes, E.C. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: Patterns and determinants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, A.; Gonzalez, G.; Carr, M.; Dean, J.; O’Byrne, E.; Aarts, L.; Vennema, H.; Banka, W.; Bennett, C.; Cleary, S.; et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus genetic diversity and lineage replacement in Ireland pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic. Microb. Genom. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, N.A.; Gonzalez, G.; Reynolds, L.J.; Bennett, C.; Campbell, C.; Nolan, T.M.; Byrne, A.; Fennema, S.; Holohan, N.; Kuntamukkula, S.R.; et al. Adeno-Associated Virus 2 and Human Adenovirus F41 in Wastewater during Outbreak of Severe Acute Hepatitis in Children, Ireland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazboudi, R.; Mulhall Maasz, H.; Resch, M.D.; Wen, K.; Gottlieb, P.; Alimova, A.; Khayat, R.; Collins, N.D.; Kuschner, R.A.; Galarza, J.M. A recombinant virus-like particle vaccine against adenovirus-7 induces a potent humoral response. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Chi, C.Y.; Kuo, P.H.; Tsai, H.P.; Wang, S.M.; Liu, C.C.; Su, I.J.; Wang, J.R. High-incidence of human adenoviral co-infections in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.; Koyanagi, K.O.; Aoki, K.; Watanabe, H. Interregional Coevolution Analysis Revealing Functional and Structural Interrelatedness between Different Genomic Regions in Human Mastadenovirus D. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6209–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Cao, J.; Liao, H.; Huang, Q.; Chen, W. The newest Oxford Nanopore R10.4.1 full-length 16S rRNA sequencing enables the accurate resolution of species-level microbial community profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0060523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Name | Tile | Start a | End a | Length b | Pool c | Sense | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B3_2500_1_LEFT | 1 | 221 | 243 | 1 | + | TTTTCCCACGCTTACTGACAGG | |

| 2 | B3_2500_1_RIGHT | 1 | 2699 | 2722 | 2501 | 1 | − | CCCCAAGCTTCTACACACGTATT |

| 3 | B3_2500_3_LEFT | 3 | 4778 | 4800 | 1 | + | GGGACCGTAAATGACCCCAATT | |

| 4 | B3_2500_3_RIGHT | 3 | 7248 | 7270 | 2492 | 1 | − | GTTACTTTCGCTTTGCCCAACC |

| 5 | B3_2500_5_LEFT | 5 | 9302 | 9324 | 1 | + | ATCTTTCAATGACCTCTCCGCG | |

| 6 | B3_2500_5_RIGHT | 5 | 11,774 | 11,796 | 2494 | 1 | − | GGTGCATCCTGTCATTGCGATA |

| 7 | B3_2500_7_LEFT | 7 | 13,796 | 13,817 | 1 | + | AGATTCGGGCGCATGTTGTAA | |

| 8 | B3_2500_7_RIGHT | 7 | 16,294 | 16,317 | 2521 | 1 | − | CAGCCCATCATCGTCATCTTCTT |

| 9 | B3_2500_9_LEFT | 9 | 18,321 | 18,343 | 1 | + | GCGCTTAACTTGCTTGTCTGTG | |

| 10 | B3_2500_9_RIGHT | 9 | 20,826 | 20,848 | 2527 | 1 | − | GTGACGGCTTTGTAGTCAGTGT |

| 11 | B3_2500_11_LEFT | 11 | 22,764 | 22,786 | 1 | + | GCCTTCATAATCGGTGCATCCA | |

| 12 | B3_2500_11_RIGHT | 11 | 25,308 | 25,330 | 2566 | 1 | − | AGTGGTAGGAGAGGTAGTTGGC |

| 13 | B3_2500_13_LEFT | 13 | 27,198 | 27,220 | 1 | + | TCTTCCTTCACTCCTCGTCAGG | |

| 14 | B3_2500_13_RIGHT | 13 | 29,654 | 29,676 | 2478 | 1 | − | ACTACCACGGCAGTAATGATGC |

| 15 | B3_2500_15_LEFT | 15 | 31,626 | 31,650 | 1 | + | CCCCCTAACAAAGTCAAACCATTC | |

| 16 | B3_2500_15_RIGHT | 15 | 34,090 | 34,112 | 2486 | 1 | − | CCGGGACCTGTTTGTAATGTGT |

| 17 | B3_1000_1_LEFT | 1 | 59 | 78 | 2 | + | AAAAAGTGCGCGCTGTGTG | |

| 18 | B3_1000_1_RIGHT | 1 | 1025 | 1047 | 988 | 2 | − | GCTCCGGACAGTCCAACTTAAA |

| 19 | B3_2500_2_LEFT | 2 | 2490 | 2512 | 2 | + | ACATATCAGGGAATGGGGCAGA | |

| 20 | B3_2500_2_RIGHT | 2 | 4942 | 4964 | 2474 | 2 | − | AAAAACTTCTCCTCGCTCCAGG |

| 21 | B3_2500_4_LEFT | 4 | 7011 | 7033 | 2 | + | GAAACCCGTCTTTTTCTGCACG | |

| 22 | B3_2500_4_RIGHT | 4 | 9559 | 9581 | 2570 | 2 | − | AAACAGTGCTCAGCCTACCTTG |

| 23 | B3_2500_6_LEFT | 6 | 11,515 | 11,537 | 2 | + | GTTGAACATCACCGAGCCTGAT | |

| 24 | B3_2500_6_RIGHT | 6 | 14,050 | 14,072 | 2557 | 2 | − | ACGAATGCTGTTTCTCCCTTCC |

| 25 | B3_2500_8_LEFT | 8 | 16,052 | 16,074 | 2 | + | AAGAGGCAATGTGTACTGGGTG | |

| 26 | B3_2500_8_RIGHT | 8 | 18,515 | 18,537 | 2485 | 2 | − | TGAAGTAGGTGTCTGTTGCACG |

| 27 | B3_2500_10_LEFT | 10 | 20,647 | 20,669 | 2 | + | GGAAGGATACAACGTGGCACAA | |

| 28 | B3_2500_10_RIGHT | 10 | 23,031 | 23,053 | 2406 | 2 | − | CATGGAAGTGATGGCTGTGCTA |

| 29 | B3_2500_12_LEFT | 12 | 25,024 | 25,046 | 2 | + | AGCTCTTGCAGAGATCCCTCAA | |

| 30 | B3_2500_12_RIGHT | 12 | 27,621 | 27,643 | 2619 | 2 | − | ATGGTTGTATTTCCCTGGTCGC |

| 31 | B3_2500_14_LEFT | 14 | 29,393 | 29,415 | 2 | + | GCAACGGAAGAGACTTGACCAT | |

| 32 | B3_2500_14_RIGHT | 14 | 31,880 | 31,902 | 2509 | 2 | − | TCTGAGGCTCCCATTAGCGTTA |

| 33 | B3_2500_16_LEFT | 16 | 32,715 | 32,737 | 2 | + | TGCGACTGCTGTTTATGGGATC | |

| 34 | B3_2500_16_RIGHT | 16 | 35,207 | 35,228 | 2513 | 2 | − | GACCGTGGGAAAATGACGTTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gonzalez, G.; Nao, N.; Tabata, K.; Itakura, Y.; Saito, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Kitaichi, N.; Ishiguro, N.; Fujimoto, T.; et al. Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing Method Reveals Endemic Circulation of Human Adenovirus Type 3 in Japan. Viruses 2026, 18, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010074

Gonzalez G, Nao N, Tabata K, Itakura Y, Saito S, Takahashi K, Kobayashi M, Kitaichi N, Ishiguro N, Fujimoto T, et al. Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing Method Reveals Endemic Circulation of Human Adenovirus Type 3 in Japan. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez, Gabriel, Naganori Nao, Koshiro Tabata, Yukari Itakura, Shinji Saito, Kenichiro Takahashi, Masaaki Kobayashi, Nobuyoshi Kitaichi, Nobuhisa Ishiguro, Tsuguto Fujimoto, and et al. 2026. "Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing Method Reveals Endemic Circulation of Human Adenovirus Type 3 in Japan" Viruses 18, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010074

APA StyleGonzalez, G., Nao, N., Tabata, K., Itakura, Y., Saito, S., Takahashi, K., Kobayashi, M., Kitaichi, N., Ishiguro, N., Fujimoto, T., Kajon, A. E., Sawa, H., & Hanaoka, N. (2026). Tiled-Amplicon Whole-Genome Sequencing Method Reveals Endemic Circulation of Human Adenovirus Type 3 in Japan. Viruses, 18(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010074