The Emerging Threat of Monkeypox: An Updated Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

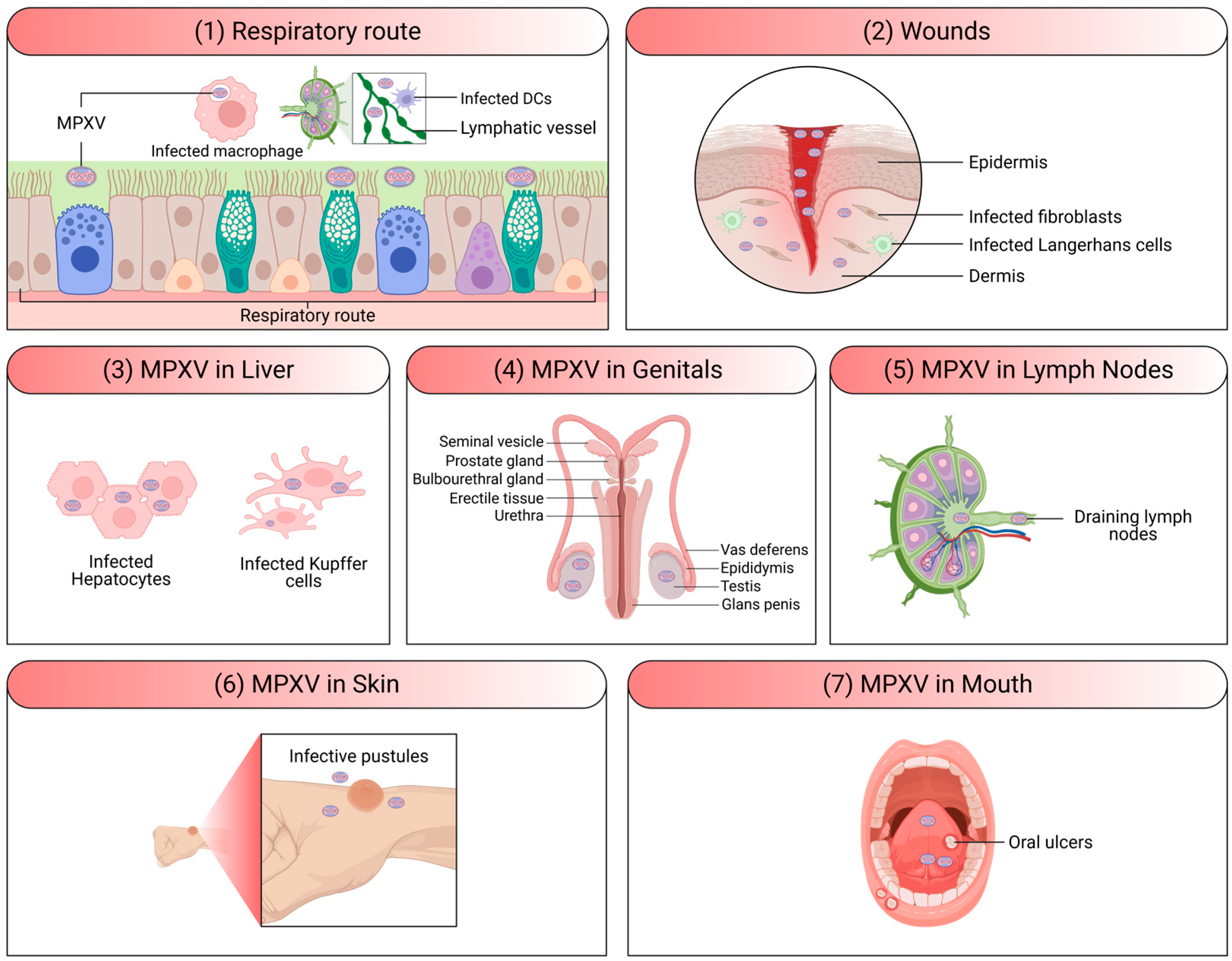

2. MPXV Infection and Pathogenesis

2.1. MPXV Structure and Genome Composition

2.2. MPXV Genotypes/Phenotypes and Epidemiological Relevance

2.3. MPXV Life Cycle

2.4. MPXV Immune Evasion Mechanisms

3. MPXV Epidemiology and Outbreaks

3.1. Historical Context and Endemic Regions

3.2. Recent MPOX Outbreaks and Global Spread

4. MPXV Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

4.1. Incubation Period and Initial Symptoms

4.2. Rash Development and Progression

4.3. Severity of Symptoms

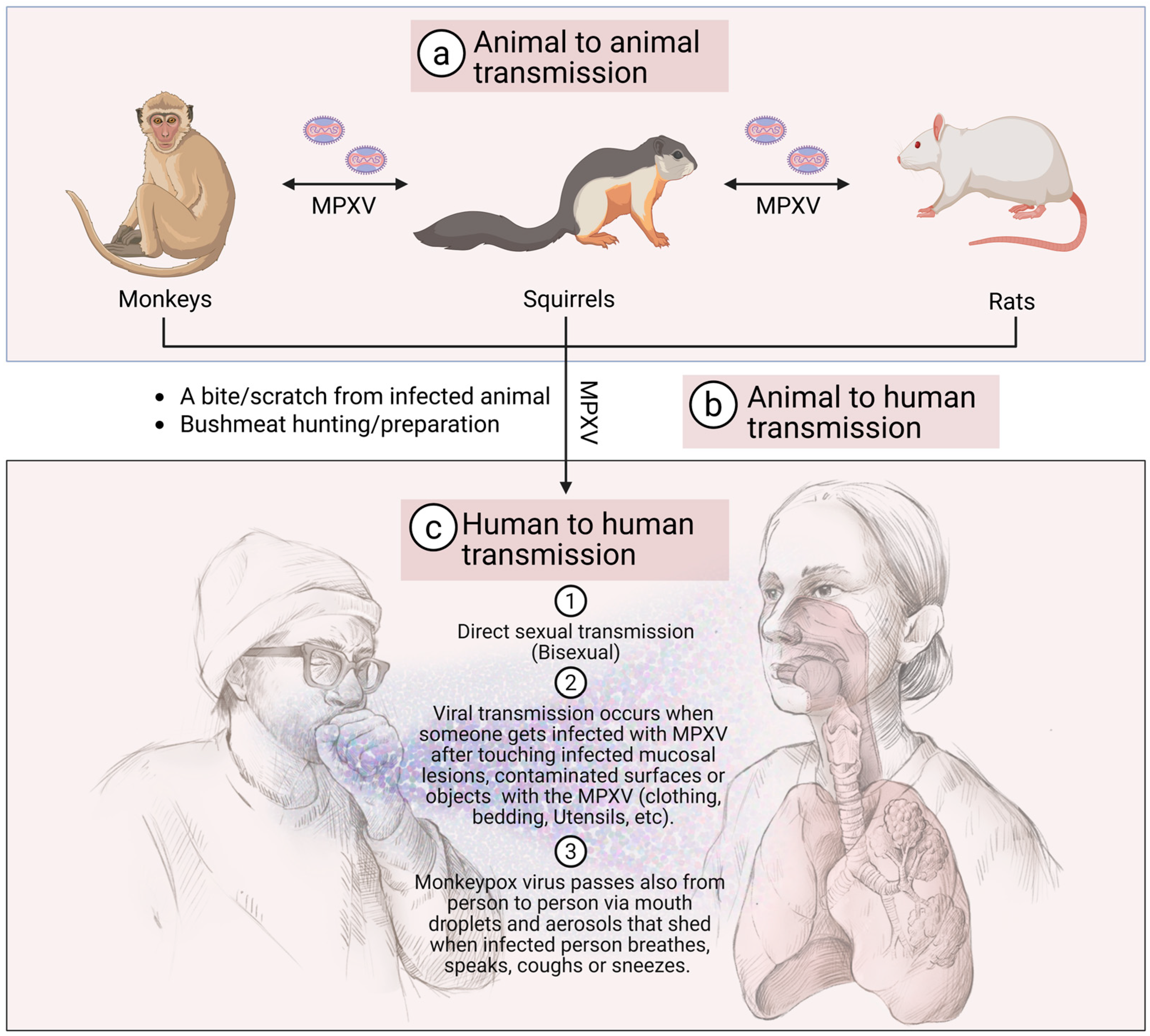

5. MPXV Transmission to Humans

5.1. Animal-to-Human Transmission

5.2. Human-to-Human Transmission

6. MPXV Risk Factors and Vulnerable Populations

6.1. Populations at Higher Risk

6.2. Occupational Exposure

7. MPOX Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

7.1. Clinical Diagnosis

7.2. Laboratory Diagnosis

7.3. Differential Diagnosis

8. MPOX Public Health Impact and Response

8.1. Impact on Endemic Regions

8.2. Global Health Concerns

8.3. Outbreak Control Measures

9. MPOX Prevention and Protection

9.1. Personal Protective Measures

9.2. Vaccination

9.2.1. Smallpox Vaccination and Cross-Protection

9.2.2. New Vaccines

9.2.3. Infection Control in Healthcare Settings

9.3. Treatment Options

9.3.1. Supportive Care

9.3.2. Antiviral Therapies

9.3.3. Immunoglobulins

10. MPOX Vaccination Strategies and Cross-Protection

10.1. Historical Context of Smallpox Vaccination

10.2. Current Vaccination Recommendations

10.3. Cross-Protection with Other Poxviruses

10.3.1. Human-to-Human Transmission

10.3.2. Geographic Spread

10.3.3. Disease Severity and Impact

10.3.4. Public Health Response and Vaccination Availability

10.3.5. Public Awareness and Compliance

11. MPXV Research and Future Directions

11.1. Ongoing Research Efforts

11.2. Challenges and Opportunities

11.3. Future Directions

12. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alakunle, E.; Kolawole, D.; Diaz-Cánova, D.; Alele, F.; Adegboye, O.; Moens, U.; Okeke, M.I. A comprehensive review of monkeypox virus and mpox characteristics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1360586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Song, A.L.; Qiu, Y.; Ge, X.-Y. Cross-species transmission and host range genes in poxviruses. Virol. Sin. 2024, 39, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadeen, C.; Van Ouwerkerk, M.; Vicek, T.; Fityan, A. A case of cowpox virus infection in the UK occurring in a domestic cat and transmitted to the adult male owner. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, R.C.; Tazi, L.; Rothenburg, S. Cowpox Viruses: A Zoo Full of Viral Diversity and Lurking Threats. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Luiz, A.P.; Fagundes-Pereira, A.; Costa, G.B.; Alves, P.A.; Oliveira, D.B.; Bonjardim, C.A.; Ferreira, P.C.; Trindade Gde, S.; Panei, C.J.; Galosi, C.M.; et al. Spread of vaccinia virus to cattle herds, Argentina, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1576–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.T.; Oliveira, G.P.; Afonso, J.A.B.; Souto, R.J.C.; de Mendonça, C.L.; Dantas, A.F.M.; Abrahao, J.S.; Kroon, E.G. An Update on the Known Host Range of the Brazilian Vaccinia Virus: An Outbreak in Buffalo Calves. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domán, M.; Fehér, E.; Varga-Kugler, R.; Jakab, F.; Bányai, K. Animal Models Used in Monkeypox Research. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arita, I.; Jezek, Z.; Khodakevich, L.; Ruti, K. Human monkeypox: A newly emerged orthopoxvirus zoonosis in the tropical rain forests of Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Dutta, P.; Rashid, R.; Jaffery, S.S.; Islam, A.; Farag, E.; Zughaier, S.M.; Bansal, D.; Hassan, M.M. Pathogenicity and virulence of monkeypox at the human-animal-ecology interface. Virulence 2023, 14, 2186357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunova, G.A.; Shchelkunov, S.N. Smallpox, Monkeypox and Other Human Orthopoxvirus Infections. Viruses 2022, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz, A.; Tombuloglu, H.; Alsaeed, M.; Tombuloglu, G.; AlRubaish, A.A.; Mahmoud, A.; Smajlović, S.; Ćordić, S.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alsuhaimi, E. Monkeypox (mpox) virus: Classification, origin, transmission, genome organization, antiviral drugs, and molecular diagnosis. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga, N.G.; Nawar, E.A.; Mobarak, A.A.; Faramawy, A.G.; Al-Kordy, H.M.H. Monkeypox: A re-emergent virus with global health implications—A comprehensive review. Trop. Dis. Travel. Med. Vaccines 2025, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdat, K.; Batyrkhan, A.; Kanayeva, D. Exploring monkeypox virus proteins and rapid detection techniques. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1414224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjo, R.; Abusara, O.H.; Sabbah, D.A.; Bardaweel, S.K. Advancing the understanding and management of Mpox: Insights into epidemiology, disease pathways, prevention, and therapeutic strategies. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xing, H.; Wang, C.; Tang, M.; Wu, C.; Ye, F.; Yin, L.; Yang, Y.; Tan, W.; Shen, L. Mpox (formerly monkeypox): Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, G.; Stoian, A.M.M.; Yu, H.; Rahman, M.J.; Banerjee, S.; Stroup, J.N.; Park, C.; Tazi, L.; Rothenburg, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Poxvirus Evolution. mBio 2023, 14, e0152622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitjà, O.; Ogoina, D.; Titanji, B.K.; Galvan, C.; Muyembe, J.-J.; Marks, M.; Orkin, C.M. Monkeypox. Lancet 2023, 401, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2003, 52, 537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenson-Schafer, H.; Sklenovská, N.; Hoxha, A.; Kerr, S.M.; Ndumbi, P.; Fitzner, J.; Almiron, M.; de Sousa, L.A.; Briand, S.; Cenciarelli, O.; et al. Description of the first global outbreak of mpox: An analysis of global surveillance data. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1012–e1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, B.; et al. Associations between the 2022 global mpox outbreak and multifaceted factors: A multi-geographical retrospective study. One Health 2025, 21, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Mpox Trends. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Likos, A.M.; Sammons, S.A.; Olson, V.A.; Frace, A.M.; Li, Y.; Olsen-Rasmussen, M.; Davidson, W.; Galloway, R.; Khristova, M.L.; Reynolds, M.G.; et al. A tale of two clades: Monkeypox viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curaudeau, M.; Besombes, C.; Nakouné, E.; Fontanet, A.; Gessain, A.; Hassanin, A. Identifying the Most Probable Mammal Reservoir Hosts for Monkeypox Virus Based on Ecological Niche Comparisons. Viruses 2023, 15, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakaniaki, E.H.; Kacita, C.; Kinganda-Lusamaki, E.; O’Toole, Á.; Wawina-Bokalanga, T.; Mukadi-Bamuleka, D.; Amuri-Aziza, A.; Malyamungu-Bubala, N.; Mweshi-Kumbana, F.; Mutimbwa-Mambo, L.; et al. Sustained human outbreak of a new MPXV clade I lineage in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2791–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthet, N.; Descorps-Declère, S.; Besombes, C.; Curaudeau, M.; Nkili Meyong, A.A.; Selekon, B.; Labouba, I.; Gonofio, E.C.; Ouilibona, R.S.; Simo Tchetgna, H.D.; et al. Genomic history of human monkey pox infections in the Central African Republic between 2001 and 2018. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheshkumar, P.; Gigante, C.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Nakazawa, Y.; Anderson, M.; Balinandi, S.; Mulei, S.; Fuller, J.; McQuiston, J.; McCollum, A.; et al. Emergence of Clade Ib Monkeypox Virus—Current State of Evidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2025, 31, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Americo, J.L.; Earl, P.L.; Moss, B. Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2220415120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer zu Natrup, C.; Clever, S.; Schünemann, L.-M.; Tuchel, T.; Ohrnberger, S.; Volz, A. Strong and early monkeypox virus-specific immunity associated with mild disease after intradermal clade-IIb-infection in CAST/EiJ-mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischauer, A.T.; Kile, J.C.; Davidson, M.; Fischer, M.; Karem, K.L.; Teclaw, R.; Messersmith, H.; Pontones, P.; Beard, B.A.; Braden, Z.H.; et al. Evaluation of human-to-human transmission of monkeypox from infected patients to health care workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, N.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Du, W.; et al. Mpox virus: Virology, molecular epidemiology, and global public health challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1624110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Duan, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiu, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Tang, G.; Cheng, L.; Zheng, P. Discovery of a Heparan Sulfate Binding Domain in Monkeypox Virus H3 as an Anti-poxviral Drug Target Combining AI and MD Simulations. eLife 2024, 13, RP100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, A.L. Comparative Pathology of Zoonotic Orthopoxviruses. Pathogens 2022, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, W.D.; Cotsmire, S.; Trainor, K.; Harrington, H.; Hauns, K.; Kibler, K.V.; Huynh, T.P.; Jacobs, B.L. Evasion of the Innate Immune Type I Interferon System by Monkeypox Virus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10489–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chiang, C.; Gack, M.U. Viral evasion of the interferon response at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs260682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.; Arunagiri, T.; Mani, S.; Kumaran, V.R.; Kannaiah, K.P.; Chanduluru, H.K. From pox to protection: Understanding Monkeypox pathophysiology and immune resilience. Trop. Med. Health 2025, 53, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainey, M.D.; Rivenbark, J.G.; Cho, H.; Yang, L.; Yokoyama, W.M. Viral MHC class I inhibition evades CD8+ T-cell effector responses in vivo but not CD8+ T-cell priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E3260–E3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund, E.; Dasgupta, A.; Pinilla, C.; Norori, P.; Früh, K.; Slifka, M.K. Monkeypox virus evades antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses by suppressing cognate T cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14567–14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, Q.Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.X.; Chen, X.H.; Ye, L.L.; Luo, Y. The land-scape of immune response to monkeypox virus. EBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karki, R.; Kanneganti, T.D. The ‘cytokine storm’: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 681–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Feng, K.; Bao, Y.; Guo, W.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y.D. Unveiling Immune Response Mechanisms in Mpox Infection Through Machine Learning Analysis of Time Series Gene Expression Data. Life 2025, 15, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Smatti, M.K.; Ouhtit, A.; Cyprian, F.S.; Almaslamani, M.A.; Thani, A.A.; Yassine, H.M. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE) and the role of complement system in disease pathogenesis. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 152, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, I.; Hamitoglu, A.E.; Hertier, U.; Belise, M.A.; Sandrine, U.; Darius, B.; Abdoulkarim, M.Y. Monkeypox Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo: A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Outcomes, Public Health Implications, and Security Measures. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e70102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladnyj, I.D.; Ziegler, P.; Kima, E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull. World Health Organ. 1972, 46, 593–597. [Google Scholar]

- Alakunle, E.; Moens, U.; Nchinda, G.; Okeke, M.I. Monkeypox Virus in Nigeria: Infection Biology, Epidemiology, and Evolution. Viruses 2020, 12, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Ji, J.; Shi, D.; Lu, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, N.; Wu, J.; Yao, H.; Li, L. Unusual global outbreak of monkeypox: What should we do? Front. Med. 2022, 16, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A.E.; Shulman, S.T. Mpox: Emergence following smallpox eradication, ongoing outbreaks and strategies for prevention. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 38, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, A.; Saleh, F.M. The resurgence of monkeypox virus: A critical global health challenge and the need for vigilant intervention. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1572100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, H.; Paansri, P.; Escobar, L.E. Global Mpox spread due to increased air travel. Geospat. Health 2024, 19, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capobianchi, M.R.; Di Caro, A.; Piubelli, C.; Mori, A.; Bisoffi, Z.; Castilletti, C. Monkeypox 2022 outbreak in non-endemic countries: Open questions relevant for public health, nonpharmacological intervention and literature review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1005955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed Kurt, D.; Melski John, W.; Graham Mary, B.; Regnery Russell, L.; Sotir Mark, J.; Wegner Mark, V.; Kazmierczak James, J.; Stratman Erik, J.; Li, Y.; Fairley Janet, A.; et al. The Detection of Monkeypox in Humans in the Western Hemisphere. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.K.; Ansari, S.; Maurya, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Paweska, J.T.; Tripathi, A.K.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S. Re-emerging human monkeypox: A major public-health debacle. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e27902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinka-Ogunleye, A.; Aruna, O.; Ogoina, D.; Aworabhi, N.; Eteng, W.; Badaru, S.; Mohammed, A.; Agenyi, J.; Etebu, E.N.; Numbere, T.W.; et al. Reemergence of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Li, Y.; Duan, Q.; Xu, D.; Li, C.; Liu, T.; Ding, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Fu, L.; et al. Genomic and phenotypic insights into the first imported monkeypox virus clade Ia isolate in China, 2025. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1618022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC. Detection of Autochthonous Transmission of Monkeypox Virus Clade Ib in the EU/EEA; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/mpox-TAB-October-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K.; El-Kader, R.G.A.; Abdulqadir, S.O.; Abdullah, A.J.; El-Shall, N.A.; Chandran, D.; Dey, A.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K. Monkeypox clinical symptoms, pathology, and advances in management and treatment options: An update. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 2837–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehrinezhad, A.; Ashayeri Ahmadabad, R.; Sahab-Negah, S. Monkeypox virus from neurological complications to neuroinvasive properties: Current status and future perspectives. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhu, B.; Qiu, Q.; Ding, N.; Wu, H.; Shen, Z. Genitourinary Symptoms Caused by Monkeypox Virus: What Urologists Should Know. Eur. Urol. 2023, 83, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Acharya, A.; Gendelman, H.E.; Byrareddy, S.N. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 131, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.D.; Park, H.S. Dissemination and Symptoms of Monkeypox Virus Infection. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2023, 35, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Monkeypox. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/monkeypox/hcp/clinical-signs/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Hussein, M.H.; Mohamad, M.A.; Dhakal, S.; Sharma, M. Cellulitis or Lymphadenopathy: A Challenging Monkeypox Virus Infection Case. Cureus 2023, 15, e40008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Nain, P.; Mukherjee, D.; Joshi, A.; Savaliya, M.; Ishak, A.; Batra, N.; Maroo, D.; Verma, D. Symptomatology, prognosis, and clinical findings of Monkeypox infected patients during COVID-19 era: A systematic-review. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntire, C.R.S.; Song, K.W.; McInnis, R.P.; Rhee, J.Y.; Young, M.; Williams, E.; Wibecan, L.L.; Nolan, N.; Nagy, A.M.; Gluckstein, J.; et al. Neurologic Manifestations of the World Health Organization’s List of Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 634827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhn, G.D.; Bauer, A.M.; Yorita, K.; Graham, M.B.; Sejvar, J.; Likos, A.; Damon, I.K.; Reynolds, M.G.; Kuehnert, M.J. Clinical characteristics of human monkeypox, and risk factors for severe disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Srivastava, U.; Gupta, S.; Rustagi, S.; Rudayni, H.A.; Kashyap, V.K.; Kumar, S. Mpox 2022 to 2025 Update: A Comprehensive Review on Its Complications, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Viruses 2025, 17, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Patterson, K.; Huggins, J.W.; Pittman, P.R. Congenital Mpox Syndrome (Clade I) in Stillborn Fetus after Placental Infection and Intrauterine Transmission, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2198–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, J.; Kim, M.; Terashita, D.; Davar, K.; Garrigues, J.M.; Guccione, J.P.; Evans, M.G.; Hemarajata, P.; Wald-Dickler, N.; Holtom, P.; et al. An Mpox-Related Death in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1246–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.M.; Rakhmanina, N.Y.; Yang, Z.; Bukrinsky, M.I. Mpox (Monkeypox) Virus and Its Co-Infection with HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, or Bacterial Superinfections: Double Whammy or a New Prime Culprit? Viruses 2024, 16, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, S.; Mohanty, A.; Thapa, N.; Poudel, P.; Bhusal, K.; Al-Qaim, Z.H.; Barboza, J.J.; Padhi, B.K.; et al. The Global Monkeypox (Mpox) Outbreak: A Comprehensive Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrati, C.; Cossarizza, A.; Mazzotta, V.; Grassi, G.; Casetti, R.; De Biasi, S.; Pinnetti, C.; Gili, S.; Mondi, A.; Cristofanelli, F.; et al. Immunological signature in human cases of monkeypox infection in 2022 outbreak: An observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Liang, D.; Ling, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xia, P.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, J.; Shi, A.; et al. Insights into monkeypox pathophysiology, global prevalence, clinical manifestation and treatments. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1132250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwishema, O.; Adekunbi, O.; Peñamante, C.A.; Bekele, B.K.; Khoury, C.; Mhanna, M.; Nicholas, A.; Adanur, I.; Dost, B.; Onyeaka, H. The burden of monkeypox virus amidst the Covid-19 pandemic in Africa: A double battle for Africa. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 80, 104197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Ding, K.; Wang, X.-H.; Sun, G.-Y.; Liu, Z.-X.; Luo, Y. The evolving epidemiology of monkeypox virus. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2022, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.B.; Ferreira de Castro, E.; Vieira da Silva, M.; Paiva Ferreira, D.C.; Jardim, A.C.G.; Santos, I.A.; Marinho, M.D.S.; Ferreira França, F.B.; Pena, L.J. In vitro and in vivo models for monkeypox. iScience 2023, 26, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. How Monkeypox Spreads. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/monkeypox/causes/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Allan-Blitz, L.T.; Klausner, J.D. Current Evidence Demonstrates That Monkeypox Is a Sexually Transmitted Infection. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2023, 50, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.D.; Maldonado, V. Behavioral aspects and the transmission of Monkeypox: A novel approach to determine the probability of transmission for sexually transmissible diseases. Infect. Dis. Model. 2023, 8, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.W. Recent advances in the diagnosis monkeypox: Implications for public health. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Emerson, G.L.; Carroll, D.S.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Reynolds, M.G.; Karem, K.L.; Olson, V.A.; Lash, R.R.; Davidson, W.B.; et al. Phylogenetic and ecologic perspectives of a monkeypox outbreak, southern Sudan, 2005. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, P.; Costa, M.A.; Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Lisboa, C. Mpox Person-to-Person Transmission-Where Have We Got So Far? A Systematic Review. Viruses 2023, 15, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, A.; Aarons, E.; Astbury, J.; Brooks, T.; Chand, M.; Flegg, P.; Hardman, A.; Harper, N.; Jarvis, R.; Mawdsley, S.; et al. Human-to-Human Transmission of Monkeypox Virus, United Kingdom, October 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 26, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiec, D.; Kirchhoff, F. Monkeypox: A New Threat? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana-González, S.; Román-López, C.; Mauss, S.; Cano-Díaz, A.L.; Mata-Marín, J.A.; Pérez-Barragán, E.; Pompa-Mera, E.; Gaytán-Martínez, J.E. Risk factors for mortality and clinical presentation of monkeypox. Aids 2023, 37, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Li, Y.; Munib, K.; Zhang, Z. Epidemiology, host range, and associated risk factors of monkeypox: An emerging global public health threat. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1160984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabbe, N.P.; Mitzey, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Razo, E.R.; Zeng, X.; Bekiares, N.; Moy, A.; Kamholz, A.; Karl, J.A.; Daggett, G.; et al. Mpox virus (MPXV) vertical transmission and fetal demise in a pregnant rhesus macaque model. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachega Jean, B.; Mohr Emma, L.; Dashraath, P.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Anderson Jean, R.; Myer, L.; Gandhi, M.; Baud, D.; Mofenson Lynne, M.; Muyembe-Tamfum, J.-J. Mpox in Pregnancy—Risks, Vertical Transmission, Prevention, and Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1267–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, B.; Scott, J.Y.; Aldredge, A.; Gromer, D.J.; Anderson, A.M.; Cartwright, E.J.; Colasanti, J.A.; Hall, B.; Jacob, J.T.; Kalapila, A.; et al. Associations Between HIV and Severe Mpox in an Atlanta Cohort. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, S234–S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.E. Monkeypox in the United States: An occupational health look at the first cases. Aaohn J. 2004, 52, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, R.; Petras, J.K.; Jenkins, P.; Gorensek, M.J.; Mableson, S.; Lee, P.A.; Carpenter, A.; Jones, H.; de Perio, M.A.; Chisty, Z.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection Resulting from an Occupational Needlestick—Florida, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1348–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkiela, M.; Wiszniewska, M.; Lipińska-Ojrzanowska, A. Monkeypox (Mpox) and Occupational Exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titanji, B.K.; Hazra, A.; Zucker, J. Mpox Clinical Presentation, Diagnostic Approaches, and Treatment Strategies: A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Kohl, A.; Pena, L.; Pardee, K. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of monkeypox (mpox): Current status and future directions. iScience 2023, 26, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frew, J.W. Monkeypox: Cutaneous clues to clinical diagnosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhteg, K.; Mostafa, H.H. Validation and implementation of an orthopoxvirus qualitative real-time PCR for the diagnosis of monkeypox in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Virol. 2023, 158, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Qu, J.; Lu, H. Molecular and immunological diagnosis of Monkeypox virus in the clinical laboratory. Drug Discov. Ther. 2022, 16, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Shin, S. Laboratory Diagnosis of Monkeypox in South Korea: Continuing the Collaboration With the Public Sector. Ann. Lab. Med. 2023, 43, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaie, M.; Arefinia, N.; Charostad, J.; Bashash, D.; Haji Abdolvahab, M.; Zarei, M. Monkeypox virus diagnosis and laboratory testing. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siami, H.; Asghari, A.; Parsamanesh, N. Monkeypox: Virology, laboratory diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J. Gene Med. 2023, 25, e3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer-Garner, I.B. Monkeypox virus: Histologic, immunohistochemical and electron-microscopic findings. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2005, 32, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, E.L.; Barra, L.A.C.; Borges, L.M.S.; Medeiros, L.A.; Tomishige, M.Y.S.; Santos, L.; Silva, A.; Rodrigues, C.C.M.; Azevedo, L.C.F.; Villas-Boas, L.S.; et al. First case report of monkeypox in Brazil: Clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis with sexually transmitted infections. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2022, 64, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Talukder, M.; Rosen, T.; Piguet, V. Differential Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of mpox (Monkeypox): A Review for Dermatologists. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, K.; Marin, M.; Gershon, A.A. Clinical Manifestations of Varicella: Disease Is Largely Forgotten, but It’s Not Gone. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, S380–S384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Fernández, D.E.; Fernández-Quezada, D.; Casillas-Muñoz, F.A.G.; Carrillo-Ballesteros, F.J.; Ortega-Prieto, A.M.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A. Human Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Strategies. Pathogens 2023, 12, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegnell, A.; Wahren, B.; Elgh, F. Smallpox—Eradicated, but a growing terror threat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 8, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H. Febrile Illness with Skin Rashes. Infect. Chemother. 2015, 47, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Kaler, J.; Lau, G.; Maxwell, T. Clinical Conundrums: Differentiating Monkeypox From Similarly Presenting Infections. Cureus 2022, 14, e29929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukaly, H.Y.; Alhawsawi, W.K.; Nassar, J.Y.; Alharbi, A.; Tayeb, S.; Rabie, N.; Alqurashi, M.; Faraj, R.; Fadag, R.; Samannodi, M. Ecthyma amidst the global monkeypox outbreak: A key differential?—A case series. IDCases 2025, 39, e02125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Sharma, D.; Sridhar, S.B.; Kumar, S.; Rao, G.; Budha, R.R.; Babu, M.R.; Sahu, R.; Sah, S.; Mehta, R.; et al. Comparative analysis of Mpox clades: Epidemiology, transmission dynamics, and detection strategies. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwibasira, G.; Dzinamarira, T.; Ngabonziza, J.C.S.; Tuyishime, A.; Ahmed, A.; Muvunyi, C.M. The Mpox Response Among Key Populations at High Risk of or Living with HIV in Rwanda: Leveraging the Successful National HIV Control Program for More Impactful Interventions. Vaccines 2025, 13, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiang, T.; Duan, J.; Huang, T.; Liu, H.; Jia, L.; Jia, H.; Yan, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Human mpox co-infection with advanced HIV-1 and XDR-TB in a MSM patient previously vaccinated against smallpox: A case report. Biosaf. Health 2024, 6, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesiga, I.; Magala, P.; Ovye, A.; Gmanyami, J.M.; Atwau, P.; Ismaila, E.; Muwonge, H.; Ediamu, T.D.; Atimango, L.; Dogo, J.M.; et al. Health system preparedness among African countries for disease outbreaks using the World Health Organisation Health systems framework: An awakening from the recent mpox outbreak. Front. Trop. Dis. 2025, 6, 1618205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, V.; Olson, V.A.; Kondas, A.V.; Jahrling, P.B.; Damon, I.K.; Kindrachuk, J. Variola Virus and Clade I Mpox Virus Differentially Modulate Cellular Responses Longitudinally in Monocytes During Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, S265–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Eid, H.; Awamleh, N.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Barakat, M.; Athamneh, R.Y.; Hallit, S.; Harapan, H.; Mahafzah, A. Conspiratorial Attitude of the General Public in Jordan towards Emerging Virus Infections: A Cross-Sectional Study Amid the 2022 Monkeypox Outbreak. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouk, M.L.; Steinig, E.; Taiaroa, G.; Savic, I.; Tran, T.; Higgins, N.; Tran, S.; Lee, A.; Braddick, M.; Moso, M.A.; et al. Intra- and interhost genomic diversity of monkeypox virus. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Pierini, M.; Mazzoli, S. Monkeypox: EpiMPX Surveillance System and Open Data with a Special Focus on European and Italian Epidemic. J. Clin. Virol. Plus 2022, 2, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamees, A.a.; Awadi, S.; Al-Shami, K.; Alkhoun, H.A.; Al-Eitan, S.F.; Alsheikh, A.M.; Saeed, A.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; Zoubi, M.S.A. Human monkeypox virus in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaraman, M.; Selvaraj, P.; Halesh, M.B.; Jeyaraman, N.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Gupta, M.; Maffulli, N.; Gupta, A. Monkeypox: An Emerging Global Public Health Emergency. Life 2022, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, I.; Zivanovic Macuzic, I.; Ilic, M. Global Outbreak of Human Monkeypox in 2022: Update of Epidemiology. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiecco, G.; Degli Antoni, M.; Storti, S.; Tomasoni, L.R.; Castelli, F.; Quiros-Roldan, E. Monkeypox, a Literature Review: What Is New and Where Does This concerning Virus Come From? Viruses 2022, 14, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashraath, P.; Nielsen-Saines, K.; Rimoin, A.; Mattar, C.N.Z.; Panchaud, A.; Baud, D. Monkeypox in pregnancy: Virology, clinical presentation, and obstetric management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 849–861.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulli, L.G.; Baldassarre, A.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G. Prevention, Risk Exposure, and Knowledge of Monkeypox in Occupational Settings: A Scoping Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Gulati, P.; Raghuvanshi, R.S. Mpox outbreak response: Regulatory and public health perspectives from India and the world. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiridou, M.; van Wees, D.A.; Adam, P.; Miura, F.; Op de Coul, E.; Reitsema, M.; de Wit, J.; van Benthem, B.; Wallinga, J. Combining mpox vaccination and behavioural changes to control possible future mpox resurgence among men who have sex with men: A mathematical modelling study. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e002682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.P.C.; Cavallaro, M.; Cumming, F.; Turner, C.; Florence, I.; Blomquist, P.; Hilton, J.; Guzman-Rincon, L.M.; House, T.; Nokes, D.J.; et al. The role of vaccination and public awareness in forecasts of Mpox incidence in the United Kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarmaji, N.; Kifli, N.; Hermansyah, A.; Yeoh, S.F.; Goh, B.H.; Ming, L.C. Prevention and Treatment of Monkeypox: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Viruses 2022, 14, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, F.; Khalil, H.E.S.; Elahmady, M.; ElBadawy, N.E.; Zahran, W.A.; Abdelnasser, M.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Wegdan, A.A.; Tash, R.M.E. Mpox: Risks and approaches to prevention. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaix, E.; Boni, M.; Guillier, L.; Bertagnoli, S.; Mailles, A.; Collignon, C.; Kooh, P.; Ferraris, O.; Martin-Latil, S.; Manuguerra, J.-C.; et al. Risk of Monkeypox virus (MPXV) transmission through the handling and consumption of food. Microb. Risk Anal. 2022, 22, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, M.; Exner, M.; Gebel, J.; Ilschner, C.; Rabenau, H.F.; Schwebke, I. Hygiene and disinfection measures for monkeypox virus infections. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2022, 17, Doc18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idris, I.; Adesola, R.O. Current efforts and challenges facing responses to Monkeypox in United Kingdom. Biomed. J. 2023, 46, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B.; Tosh, P.K. Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: A rapid review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e349–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Duan, J.; Huang, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, T. Global perspectives on smallpox vaccine against monkeypox: A comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review of effectiveness, protection, safety and cross-immunogenicity. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2387442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, A.F.; Diallo, A.O.; Chard, A.N.; Moulia, D.L.; Deputy, N.P.; Fothergill, A.; Kracalik, I.; Wegner, C.W.; Markus, T.M.; Pathela, P.; et al. Estimated Effectiveness of JYNNEOS Vaccine in Preventing Mpox: A Multijurisdictional Case-Control Study—United States, August 19, 2022–March 31, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deputy, N.P.; Deckert, J.; Chard, A.N.; Sandberg, N.; Moulia, D.L.; Barkley, E.; Dalton, A.F.; Sweet, C.; Cohn, A.C.; Little, D.R.; et al. Vaccine Effectiveness of JYNNEOS against Mpox Disease in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2434–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, J.; Graham, B.S. Smallpox vaccines: Past, present, and future. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, F.; Hasan, T.B.; Alam, F.; Das, A.; Afrin, S.; Maisha, S.; Masud, A.A.; Km, S.U. Effect of prior immunisation with smallpox vaccine for protection against human Mpox: A systematic review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, N.; Haq, Z.U.; Malik, A.; Mehmood, A.; Ishaq, U.; Faraz, M.; Malik, J.; Mehmoodi, A. Human monkeypox virus: An updated review. Medicine 2022, 101, e30406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J.M.; Muller, S. Monkeypox: Potential vaccine development strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soheili, M.; Nasseri, S.; Afraie, M.; Khateri, S.; Moradi, Y.; Mahdavi Mortazavi, S.M.; Gilzad-Kohan, H. Monkeypox: Virology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Characteristics, Epidemiology, Vaccines, Diagnosis, and Treatments. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 25, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, A.; Reda, A.; Lashin, B.I.; Katamesh, B.E.; Brakat, A.M.; Al-Manaseer, B.M.; Kaur, S.; Asija, A.; Patel, N.K.; Basnyat, S.; et al. Preventing the Next Pandemic: Is Live Vaccine Efficacious against Monkeypox, or Is There a Need for Killed Virus and mRNA Vaccines? Vaccines 2022, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, Y.P.; Lee, C.C.; Lee, J.C.; Chiu, C.W.; Hsueh, P.R.; Ko, W.C. A brief on new waves of monkeypox and vaccines and antiviral drugs for monkeypox. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, R.M.; Elrewany, E.; Gebreal, A.; ElMakhzangy, R.; Fadl, N.; Elbanna, E.H.; Tolba, M.M.; Hammad, E.M.; Youssef, N.; Abosheaishaa, H.; et al. Systematic Review on the Efficacy, Effectiveness, Safety, and Immunogenicity of Monkeypox Vaccine. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, M.; Mandal, R.K.; Sikander, M.; Khan, M.R.; Haque, S.; Nagda, N.; Ahmad, F.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Safety and Efficacy of Repurposed Smallpox Vaccines Against Mpox: A Critical Review of ACAM2000, JYNNEOS, and LC16. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyamvada, L.; Carson, W.C.; Ortega, E.; Navarra, T.; Tran, S.; Smith, T.G.; Pukuta, E.; Muyamuna, E.; Kabamba, J.; Nguete, B.U.; et al. Serological responses to the MVA-based JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine in a cohort of participants from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Vaccine 2022, 40, 7321–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriss, J.L.; Boersma, P.M.; Martin, E.; Reed, K.; Adjemian, J.; Smith, N.; Carter, R.J.; Tan, K.R.; Srinivasan, A.; McGarvey, S.; et al. Receipt of First and Second Doses of JYNNEOS Vaccine for Prevention of Monkeypox—United States, May 22–October 10, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.B.; Ray, L.C.; Kugeler, K.J.; Fothergill, A.; White, E.B.; Canning, M.; Farrar, J.L.; Feldstein, L.R.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Houck, K.; et al. Incidence of Monkeypox Among Unvaccinated Persons Compared with Persons Receiving ≥1 JYNNEOS Vaccine Dose—32 U.S. Jurisdictions, July 31–September 3, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katamesh, B.E.; Madany, M.; Labieb, F.; Abdelaal, A. Monkeypox pandemic containment: Does the ACAM2000 vaccine play a role in the current outbreaks? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 22, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Al-Masri, A.A.; Klonoff, D.C.; Alshahrani, A.N.; Al-Khlaiwi, T. Comparison of Biological, Pharmacological Characteristics, Indications, Contraindications and Adverse Effects of JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 Monkeypox Vaccines. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, A.; Prigge, J.T.; Silvera, P.M.; Honeychurch, K.M.; Hruby, D.E.; Grosenbach, D.W. Treatment with the smallpox antiviral tecovirimat (ST-246) alone or in combination with ACAM2000 vaccination is effective as a postsymptomatic therapy for monkeypox virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4296–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Mandia, J.; Keltner, C.; Haynes, R.; Faestel, P.; Mease, L. Monkeypox in Patient Immunized with ACAM2000 Smallpox Vaccine During 2022 Outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 2336–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeel, M.; Morsy, M.A.; Abd El-Lateef, H.M.; Marzok, M.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Al Khodair, K.M.; Albokhadaim, I.; Venugopala, K.N. Efficacy of the modified vaccinia Ankara virus vaccine and the replication-competent vaccine ACAM2000 in monkeypox prevention. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 119, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehn, R.; Fox, T.; Guyatt, G.; Lutje, V.; Gould, S. Infection prevention and control measures to reduce the transmission of mpox: A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, R.S.; Rodrigues Ikeda, M.L.; Barcellos, R.B.; Godinho, F.M.; Sesterheim, P.; Bitencourt, L.C.B.; Gregianini, T.S.; Gorini da Veiga, A.B.; Spilki, F.R.; Wallau, G.L. Possible Occupational Infection of Healthcare Workers with Monkeypox Virus, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 2520–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. EPA Releases List of Disinfectants for Emerging Viral Pathogens (EVPs) Including Monkeypox. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/epa-releases-list-disinfectants-emerging-viral-pathogens-evps-including-monkeypox (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Reynolds, M.G.; McCollum, A.M.; Nguete, B.; Shongo Lushima, R.; Petersen, B.W. Improving the Care and Treatment of Monkeypox Patients in Low-Resource Settings: Applying Evidence from Contemporary Biomedical and Smallpox Biodefense Research. Viruses 2017, 9, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanadaiah, P.; Kumar, G.A.; Babu, M.R.; Vishwas, S.; Chaitanya, M.V.N.L.; Pal, B.; Kumar, R.; Zandi, M.; Gupta, G.; MacLoughlin, R.; et al. Unravelling the Treatment Strategies for Monkeypox Virus: Success and Bottlenecks. Rev. Med. Virol. 2025, 35, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.M.; Zheng, Y.J.; Zhou, L.; Feng, L.Z.; Ma, L.; Xu, B.P.; Xu, H.M.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.D.; Deng, J.K.; et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of monkeypox in children: An experts’ consensus statement. World J. Pediatr. 2023, 19, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, T.; Chakole, S.; Agrawal, S.; Gupta, A.; Munjewar, P.K.; Sharma, R.; Yelne, S. Enhancing Nursing Care in Monkeypox (Mpox) Patients: Differential Diagnoses, Prevention Measures, and Therapeutic Interventions. Cureus 2023, 15, e44687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabbir, M.; Bugayong, M.L.; DeVita, M.A. Mpox Pain Management with Topical Agents: A Case Series. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2023, 37, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, S.; Lamb, T.; Jackson, E.; Beech, A.; Malik, N.; Johnson, L.; Jacobs, N. Assessment and management of secondary bacterial infections complicating Mpox (Monkeypox) using a telemedicine service. A prospective cohort study. Int. J. STD AIDS 2023, 34, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, G.; Buccoliero, G.B. Antivirals against Monkeypox (Mpox) in Humans: An Updated Narrative Review. Life 2023, 13, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, E.A.; Sassine, J. Antivirals With Activity Against Mpox: A Clinically Oriented Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrareddy, S.N.; Sharma, K.; Sachdev, S.; Reddy, A.S.; Acharya, A.; Klaustermeier, K.M.; Lorson, C.L.; Singh, K. Potential therapeutic targets for Mpox: The evidence to date. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, J.; Sloan, A.; Deschambault, Y.; Tailor, N.; Tierney, K.; Azaransky, K.; Kammanadiminti, S.; Barker, D.; Kodihalli, S.; Safronetz, D. Treatment efficacy of cidofovir and brincidofovir against clade II Monkeypox virus isolates. Antivir. Res. 2024, 231, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, A.; Rimmer, S.; Gilchrist, M.; Sun, K.; Davies, E.P.; Waddington, C.S.; Chiu, C.; Armstrong-James, D.; Swaine, T.; Davies, F.; et al. Use of cidofovir in a patient with severe mpox and uncontrolled HIV infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e218–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, M.A.; Satapathy, P.; Padhi, B.K.; Veeramachaneni, S.D.; Akhtar, N.; Pradhan, A.; Agrawal, A.; Dwivedi, P.; Mohanty, A.; Pradhan, K.B.; et al. Pharmacological treatment and vaccines in monkeypox virus: A narrative review and bibliometric analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1149909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchlinsky, M.; Albright, A.; Olson, V.; Schiltz, H.; Merkeley, T.; Hughes, C.; Petersen, B.; Challberg, M. The development and approval of tecoviromat (TPOXX(®)), the first antiviral against smallpox. Antivir. Res. 2019, 168, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzia, B.; Theotoka, D.; Li, K.; Moss, E.; Matesva, M.; Gill, M.; Kibe, M.; Chow, J.; Green, S. Treatment of ocular-involving monkeypox virus with topical trifluridine and oral tecovirimat in the 2022 monkeypox virus outbreak. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 29, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Alshammari, M.K.; Arora, M.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Das, S.S.; Kamal, M.; Alqahtani, A.S.A.; Sahloly, M.A.Y.; Alshammari, A.H.; Alhomam, H.M.; et al. Oral Brincidofovir Therapy for Monkeypox Outbreak: A Focused Review on the Therapeutic Potential, Clinical Studies, Patent Literature, and Prospects. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittek, R. Vaccinia immune globulin: Current policies, preparedness, and product safety and efficacy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadh, M.J.; Ghadimkhani, T.; Soltani, N.; Abbassioun, A.; Daniel Cosme Pecho, R.; taha, A.; Jwad Kazem, T.; Yasamineh, S.; Gholizadeh, O. Progress and prospects on vaccine development against monkeypox infection. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 180, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassburg, M.A. The global eradication of smallpox. Am. J. Infect. Control 1982, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Pan, B.; Jiang, H.J.; Zhang, Q.M.; Xu, X.W.; Jiang, H.; Ye, J.E.; Cui, Y.; Yan, X.J.; Zhai, X.F.; et al. The willingness of Chinese healthcare workers to receive monkeypox vaccine and its independent predictors: A cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, R.M.; Yazbek, S.; Gebreal, A.; Hussein, M.; Addai, S.A.; Mensah, E.; Sarfo, M.; Kofi, A.; Al-Ahdal, T.; Eshun, G. Monkeypox Vaccine Acceptance among Ghanaians: A Call for Action. Vaccines 2023, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z. Comparative risk perception of the monkeypox outbreak and the monkeypox vaccine. Risk Anal. 2024, 44, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, G.O.; Emanuel, E.J.; Atuire, C.A.; Leland, R.J.; Persad, G.; Richardson, H.S.; Saenz, C. Equitable global allocation of monkeypox vaccines. Vaccine 2023, 41, 7084–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.K.; Minhaj, F.S.; Carter, R.J.; Duffy, J.; Satheshkumar, P.S.; Delaney, K.P.; Quilter, L.A.S.; Kachur, R.E.; McLean, C.; Moulia, D.L.; et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Mpox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for Persons Aged ≥18 Years at Risk for Mpox During an Mpox Outbreak: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2025, 74, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogacka, A.; Wroczynska, A.; Rymer, W.; Grzesiowski, P.; Kant, R.; Grzybek, M.; Parczewski, M. Mpox unveiled: Global epidemiology, treatment advances, and prevention strategies. One Health 2025, 20, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, O.P.; Priyanka; Fahrni, M.L.; Saied, A.A.; Chopra, H. Ring vaccination for monkeypox containment: Strategic implementation and challenges. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 105, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Vaccines and Immunization for Monkeypox: Interim Guidance. 16 November 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Immunization (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- CDC. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of Vaccine for Monkeypox Prevention in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/monkeypox/hcp/vaccine-considerations/vaccination-overview.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Galetti, S.C.; Gadoth, A.; Halbrook, M.; Tobin, N.H.; Ferbas, K.G.; Rimoin, A.W.; Aldrovandi, G.M. Historic smallpox vaccination and Mpox cross-reactive immunity: Evidence from healthcare workers with childhood and adulthood exposures. Vaccine 2025, 46, 126661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchuk, I.; Gilchuk, P.; Sapparapu, G.; Lampley, R.; Singh, V.; Kose, N.; Blum, D.L.; Hughes, L.J.; Satheshkumar, P.S.; Townsend, M.B.; et al. Cross-Neutralizing and Protective Human Antibody Specificities to Poxvirus Infections. Cell 2016, 167, 684–694.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchuk, I.; Blum, D.; Fritz, G.; Singh, V.; Kose, N.; Yu, Y.; Sapparapu, G.; Matho, M.; Zajonc, D.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Poxviral infection elicits human neutralizing antibodies recognizing diverse epitopes of the major vaccinia virus surface protein D8 (VIR4P.1016). J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 143.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchuk, I.; Gilchuk, P.; Hammarlund, E.; Slifka, M.; Lampley, R.; Sapparapu, G.; Eisenberg, R.; Cohen, G.; Xiang, Y.; Joyce, S.; et al. Human antibody specificities that confer protective immunity to poxvirus infections (VAC11P.1109). J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 212.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.; Nguyen, L.L.; Breban, R. Modelling human-to-human transmission of monkeypox. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, S.; Zange, S.; Seilmaier, M.; Antwerpen, M.H.; Fenzl, T.; Schneider, J.; Spinner, C.D.; Bugert, J.J.; Wendtner, C.M.; Wölfel, R. Clinical and virological features of first human monkeypox cases in Germany. Infection 2023, 51, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, F.; van Ewijk, C.E.; Backer, J.A.; Xiridou, M.; Franz, E.; Op de Coul, E.; Brandwagt, D.; van Cleef, B.; van Rijckevorsel, G.; Swaan, C.; et al. Estimated incubation period for monkeypox cases confirmed in the Netherlands, May 2022. Euro. Surveill. 2022, 27, 2200448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetta, G.; Mammone, A.; Ferraro, F.; Caraglia, A.; Rapiti, A.; Marziano, V.; Poletti, P.; Cereda, D.; Vairo, F.; Mattei, G.; et al. Early Estimates of Monkeypox Incubation Period, Generation Time, and Reproduction Number, Italy, May–June 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 2078–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, H. The classical definition of a pandemic is not elusive. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S.A.; Klonoff, D.C. Human monkeypox outbreak: Global prevalence and biological, epidemiological and clinical characteristics—Observational analysis between 1970–2022. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 5624–5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.L.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Wu, J.; Kong, J.D.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Woldegerima, W.A. Risk factors associated with human Mpox infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apea, V.; Titanji, B.K.; Dakin, F.H.; Hayes, R.; Smuk, M.; Kawu, H.; Waters, L.; Levy, I.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Gandhi, M.; et al. International healthcare workers’ experiences and perceptions of the 2022 multi-country mpox outbreak. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0003704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damijan, J.P.; Damijan, S.; Kostevc, Č. Vaccination Is Reasonably Effective in Limiting the Spread of COVID-19 Infections, Hospitalizations and Deaths with COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.D.; Hart, W.S.; Thompson, R.N.; Ishikane, M.; Nishiyama, T.; Park, H.; Iwamoto, N.; Sakurai, A.; Suzuki, M.; Aihara, K.; et al. Modelling the effectiveness of an isolation strategy for managing mpox outbreaks with variable infectiousness profiles. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delea, K.C.; Chen, T.H.; Lavilla, K.; Hercules, Y.; Gearhart, S.; Preston, L.E.; Hughes, C.M.; Minhaj, F.S.; Waltenburg, M.A.; Sunshine, B.; et al. Contact Tracing for Mpox Clade II Cases Associated with Air Travel—United States, July 2021–August 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiem, K.; Nogales, A.; Lorenzo, M.; Morales Vasquez, D.; Xiang, Y.; Gupta, Y.K.; Blasco, R.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. Identification of In Vitro Inhibitors of Monkeypox Replication. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0474522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A.; Pan, Q. Preventing drug resistance: Combination treatment for mpox. Lancet 2023, 402, 1750–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witwit, H.; Cubitt, B.; Khafaji, R.; Castro, E.M.; Goicoechea, M.; Lorenzo, M.M.; Blasco, R.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; de la Torre, J.C. Repurposing Drugs for Synergistic Combination Therapies to Counteract Monkeypox Virus Tecovirimat Resistance. Viruses 2025, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, R.; Antonio, E.; de Swart, M.; Foster, I.; Cerrado, J.P.; Kadri-Alabi, Z.; Ibrahim, S.K.; Ashley, L.; Ndwandwe, D.; Sigfrid, L.; et al. Gaps in the global health research landscape for mpox: An analysis of research activities and existing evidence. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antiviral Agent | Mechanism of Action | Administration Route | Approved Uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tecovirimat (known as TPOXX or ST-246) | Inhibition of the viral envelope protein VP37, which is essential for viral release from infected cells. By preventing maturation and release of new viral particles, it reduces the spread of the virus within the host. | Oral tablets or intravenous (IV) | Approved for smallpox; off-label use for MPXV | [166,167] |

| Brincidofovir (known as Tembexa, CMX001 or HDP-CDV) | Inhibition of viral DNA polymerase, an enzyme crucial for viral DNA replication. This action prevents the virus from multiplying and spreading. | Oral tablets | Approved for smallpox; off-label use for MPXV | [163,168] |

| Cidofovir | Inhibition of viral DNA polymerase. Generally, it is less preferred than Brincidofovir due to potential nephrotoxicity. Its mechanism of action is similar to Brincidofovir, interfering with viral DNA replication. | Intravenous (IV) | Off-label use for various poxviruses, including MPXV | [163,164] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yahya, G.; Mohamed, N.H.; Wadan, A.-H.S.; Castro, E.M.; Kamel, A.; Abdelmoaty, A.A.; Alsadik, M.E.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Mostafa, A. The Emerging Threat of Monkeypox: An Updated Overview. Viruses 2026, 18, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010069

Yahya G, Mohamed NH, Wadan A-HS, Castro EM, Kamel A, Abdelmoaty AA, Alsadik ME, Martinez-Sobrido L, Mostafa A. The Emerging Threat of Monkeypox: An Updated Overview. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleYahya, Galal, Nashwa H. Mohamed, Al-Hassan Soliman Wadan, Esteban M. Castro, Amira Kamel, Ahmed A. Abdelmoaty, Maha E. Alsadik, Luis Martinez-Sobrido, and Ahmed Mostafa. 2026. "The Emerging Threat of Monkeypox: An Updated Overview" Viruses 18, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010069

APA StyleYahya, G., Mohamed, N. H., Wadan, A.-H. S., Castro, E. M., Kamel, A., Abdelmoaty, A. A., Alsadik, M. E., Martinez-Sobrido, L., & Mostafa, A. (2026). The Emerging Threat of Monkeypox: An Updated Overview. Viruses, 18(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010069